Peasant Character Studies (Van Gogh series)

| Woman Sewing | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1881–82 |

| Catalogue | F869 |

| Type | Watercolor |

| Location | P. and N. de Boer Foundation, Amsterdam |

Peasant Character Studies is a series of works that Vincent van Gogh made between 1881 and 1885.

Van Gogh had a particular attachment and sympathy for peasants and other working class people that was fueled in several ways. He was particularly fond of the peasant genre work of Jean-François Millet and others. He found the subjects noble and important in the development of modern art. Van Gogh had seen the changing landscape in the Netherlands as industrialization encroached on once pastoral settings and the livelihoods of the working poor with little opportunity to change vocation.

Van Gogh had a particular interest in creating character studies of working men and women in the Netherlands and Belgium, such as farmers, weavers, and fishermen. Making up a large body of Van Gogh's work during this period, the character studies were an important, foundational component in his artistic development.

Background

[edit]Peasant genre

[edit]

The "peasant genre" of the Realism movement began in the 1840s with the works of Jean-François Millet, Jules Breton, and others. Van Gogh described the works of Millet and Breton as having religious significance, "something on high," and described them as being the "voices of the wheat."[1]

The Van Gogh Museum says of Millet's influence on Van Gogh: "Millet's paintings, with their unprecedented depictions of peasants and their labors, mark a turning point in 19th-century art. Before Millet, peasant figures were just one of many elements in picturesque or nostalgic scenes. In Millet's work, individual men and women became heroic and real. Millet was the only major artist of the Barbizon School who was not interested in 'pure' landscape painting."[2]

Artistic development and influences

[edit]In 1880, when he was 27 years old, Van Gogh decided to become an artist. In October of that year he moved to Brussels and began a beginner's course of study.[3]

Van Gogh returned to Etten in April 1881 to live with his parents and studied art on his own. His younger brother Theo, an art dealer at the main branch of Goupil & Cie, encouraged him and started covering Van Gogh's expenses.[3]

Van Gogh used images from illustrated magazines to teach himself how to draw. Charles Bargue, a French artist, wrote two books on drawing that were a significant source of study for Van Gogh. Both written in 1871, one is "Cours de dessin" and the other "Exercises au fusain pour préparer à l’étude de l’académie d’après nature," Van Gogh created copies of the drawings or adapted nude images for clothed depictions.[4]

In January 1882, he settled in The Hague where he called on his cousin-in-law, the painter Anton Mauve (1838–88). Mauve introduced him to painting in both oil and watercolor and lent him money to set up a studio.[5]

Van Gogh began drawing people from the working poor, including the prostitute Clasina Maria "Sien" Hoornik (1850–1904), with whom he would become involved. Van Gogh dreamed his studio would one day become a form of respite for the poor where they could receive food, shelter and money for posing.[6][7] His work was not well received; Mauve and H.G. Tersteeg, manager of Goupil & Cie, considered the drawings coarse and lacking charm. Van Gogh likened the "unrefined" characteristics of his drawings to harsh "yellow soap" made of lye.[8]

Van Gogh's relationship with Sien changed as they lived together with Maria, her five-year-old daughter, to the great disappointment of his family.[3]

Mauve appears to have suddenly gone cold towards Van Gogh and did not return a number of his letters.[9] Van Gogh supposed that Mauve did not approve of his domestic arrangement with Sien[6] and her young daughter.[10][11] Van Gogh created a number of drawings of Sien and her daughter. Having ended his relationship with Sien, Van Gogh moved to Drenthe in September 1883 and painted landscapes. Three months later, he moved back in with his parents, who were at that point living in Nuenen.[3]

In 1884, Van Gogh created the weaver series, works of rural life and landscapes.[3] For a brief period of time, he gave painting lessons in Eindhoven.[12] Near the end of the year, Van Gogh began experimenting with complementary colors, influenced by the color theories of Charles Blanc.[13]

Vincent made many studies of peasants in 1885, culminating in his first major painting, The Potato Eaters.[3] In his works, Van Gogh used particularly somber colors and colors mixed with black, which he felt was like that of 17th-century masters, such as Frans Hals. His brother, Theo van Gogh (art dealer) had asked him often to lighten up his work, referring to the work of the Impressionists. Once Van Gogh went to Paris, he did open up his palette to color and light and admitted that his works from this period were old-fashioned.[14]

Theodorus van Gogh, Vincent's father, died March 26, 1885. In November, Vincent moved to Antwerp.[3]

Regard for peasants and manual laborers

[edit]Throughout Van Gogh's adulthood he had an interest in serving others, especially manual workers. As a young man, he served and ministered to coal miners in Borinage, Belgium, which seemed to bring him close to his calling of being a missionary or minister to workers.[15]

He held laborers up to a high standard of the dedication with which he should approach painting, "One must undertake with confidence, with a certain assurance that one is doing a reasonable thing, like the farmer who drives his plow... (one who) drags the harrow behind himself. If one hasn't a horse, one is one's own horse."[15]

The close association of peasants and the cycles of nature particularly interested Van Gogh, such as the sowing of seeds, harvest and sheaves of wheat in the fields.[1] Van Gogh saw plowing, sowing and harvesting symbolic to man's efforts to overwhelm the cycles of nature.[1]

Industrialization

[edit]Van Gogh was extremely mindful of the impact of 19th-century industrialization on the changing landscape and what that meant to people's lives. Van Gogh wrote in a letter to Anthon van Rappard:

"I remember as a boy seeing that heath and the little farms, the looms and the spinning wheels in exactly the same way as I see them now in Anton Mauve’s and Adam Frans van der Meulen’s drawings… But since then that part of Brabant with which I was acquainted has changed enormously in consequence of agricultural developments and the establishment of industries. Speaking for myself, in certain spots I do not look without a little sadness on a new red-tiled tavern, remembering a loam cottage with a moss-covered thatched roof that used to be there. Since then there have come beet-sugar factories, railways, agricultural developments of the heath, etc., which is infinitely less picturesque."[16]

Peasant character studies

[edit]

In November 1882, Van Gogh began drawings of individuals to depict a range of character types from the working class.[17] He aimed to be a "peasant painter", conveying deep feeling realistically, with objectivity.[18]

To depict the essence of the life of the peasant and their spirit, Van Gogh lived as they lived, he was in the fields as they were, enduring the weather for long hours as they were. To do so was not something taught in schools, he noted, and became frustrated by traditionalists who focused on technique more so than the nature of the people being captured.[19] So thoroughly was he engaged in living the peasant lifestyle, his appearance and manner of speech began to separate himself from others, but this was a cost he believed he needed to bear for his artistic development.[20] Of getting along better with "poor and common folk" than cultured society, Van Gogh wrote in 1882, "after all, it's right and proper that I should live like an artist in the surroundings I'm sensitive to and am trying to express."[21]

Women

[edit]Van Gogh made many studies of women, a large number made in 1885. Of painting women, Van Gogh commented that he preferred to paint women in blue denim rather than his sisters in refined dresses.[7] This is a sampling of some of his works.

Gordina de Groot (called Sien by Hulsker on the strength of a single reference to the name in van Gogh's letters), who sat for Head of a Woman (F160), was one of the daughters of the De Groot family, the subjects of The Potato Eaters (Gordina is the figure on the left in that painting). Van Gogh made at least 20 studies while in Nuenen of Gordina, who possessed the "coarse, flat faces, low foreheads and thick lips, not sharp but full" of peasants that he admired in Jean-François Millet's work. Vincent signed this study, one of the few character studies that he signed.[22]

Head of a woman, 1884 (F1182, the image is not shown), was a drawing Van Gogh made of a peasant woman from Nuenen. Her face, worn by a difficult life, is symbolic of the peasant's hard life. Van Gogh made the studies of heads, arms and hands and building blocks for the large painting The Potato Eaters that he made in 1885.[23]

The working class woman in Head of a Woman with her Hair Loose (F206) is portrayed with seeming eroticism, her hair disheveled and in a state of undress.[7] In July 2022, an x-ray of the painting Head of a Peasant Woman with White Cap uncovered a hidden self-portrait of Van Gogh on the back of the original artwork.[24]

-

Head of a Woman, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F160)

-

Head of a Peasant woman with white hood (Gordina de Groot), 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F85)

-

Fisherman's Wife on the Beach, 1882, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F6)

-

Peasant Woman, Half Figure, Seated with White Cap, 1884, Morohashi Museum of Modern Art, Fukushima, Japan (F143)

-

Head of a Woman with her Hair Loose, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F206)

-

Head of a Peasant Woman with Dark Cap, 1885, National Gallery London(F137)

-

Peasant Woman Taking her Meal, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F72)

-

Peasant Woman Sitting on a Chair, 1885, Private collection (F126)

-

Head of a Peasant Woman with White Cap, 1885, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh (F140)

-

Head of an Old Peasant Woman with White Cap, 1884, Private collection (F146)

Men

[edit]Van Gogh's studies of men are primarily at work; here are the studies that he made of their heads or figure.

Desiring to make studies of peasants in Drenthe during his three-month stay in 1883, Van Gogh had difficulty finding people willing to pose for him.[25] In Nuenen the situation was different. It was winter and there was little to be done in the fields. In addition, he had connections to people through his father, a town minister. In Nuenen, Van Gogh was able to produce a large number of works of peasant's heads, such as the Head of a Man (F164) completed in 1885.[26]

-

Fisherman on the Beach, 1882, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F5)

-

The Fisherman (Facing Right), 1882. Private collection (F1049)

-

Peasant from Nuenen, 1885, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels (F163)

-

Head of a Man with a Pipe, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F169)

-

Head of a Man, 1884–85, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F164)

-

Head of a Young Peasant in a Peaked Cap (b/w copy of painting), 1885, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Fine Art, Kansas City (F165)

-

Head of a Man, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F168)

-

Head of a Peasant with a Cap, 1885, Collection Niarchos (F169a)

Gender roles

[edit]Women

[edit]Home and child care

[edit]Peasant Woman Cooking by a Fireplace (F176) was painted by Van Gogh in 1885 following the completion of The Potato Eaters. Both paintings were made in dark hues like "green soap" or a "good dusty potato." Seeking realism, Van Gogh was "convinced that in the long run to portray peasants in their coarseness gives better results than introducing conventional sweetness. If a peasant painting smells of bacon, smoke, potato steam, very well, that's not unhealthy; if a stable smells of manure, alright, that's why it's a stable..."[27]

Peasant Woman Peeling Potatoes, also called The Potato Peeler, was painted by Van Gogh in 1885, the year before he left the Netherlands for France. It is typical of the peasant studies that he made in Nuenen, "with its restricted palette of dark tones, coarse fracture, and blocky drawing."[28]

-

Sien Nursing Baby, watercolor and chalk, 1882, Private collection (F1068)

-

Peasant Woman with Child on Her Lap, 1885, Private collection (F149)

-

Head of an Old Woman with White Cap (The Midwife), 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F174)

-

Peasant Woman Seated before an Open Door, Peeling Potatoes (b/w copy of painting), 1885, Private collection (F73)

-

Peasant Woman Peeling Potatoes, 1885, Private collection (F145)

-

Peasant Woman Peeling Potatoes, 1885, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F365r)

-

Peasant Woman Cooking by a Fireplace, 1885, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (F176)

-

Woman with a Broom also Woman Sweeping the Floor, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F152)

-

Peasant Woman Laundering, 1885, Private collection (F148)

Farm and other labor

[edit]Van Gogh described Peasant Woman Digging (F95a) as a "woman ... seen from the front, her head almost on the ground, digging carrots". Made in Nuenen in 1885, this painting was part of the peasant studies Van Gogh conducted to "catch their character."[29]

Peasant Woman Digging in Front of Her Cottage (F142) was one of the paintings that Van Gogh left behind when he went to Antwerp in 1885 and went to his mother Anna Carbentus van Gogh.[30]

-

Two Women in the Moor, 1883, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F19)

-

Peasant Woman Digging, 1885, Noordbrabants, Den Bosch (F94)

-

Peasant Woman Digging also Woman with a Spade, Seen from Behind, 1885, The Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (F95)

-

Peasant Woman Digging, 1885, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham (F95a)

-

Two Peasant Women Digging (b/w copy of painting), 1885, Private collection (F96)

-

Two Peasant Women Digging Potatoes, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F97 - also F129)

-

Peasant Woman Digging Up Potatoes, 1885, Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium (F98)

-

Woman with Wheelbarrow, watercolor, 1883, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F1021)

-

Peasant Woman Raking, 1885, Private collection (F139)

-

Peasant Woman Digging in Front of Her Cottage, 1885, Art Institute of Chicago (F142)

Sewing and winding yarn

[edit]Woman Sewing (F71) depicts a woman seated at a window. In this study Van Gogh was experimenting with how to reflect an interior figure, backlit by a window. Here the woman is a dark silhouette. Van Gogh shows the effect of the light streaming in the window on her sewing. In 1885 Van Gogh wrote his brother Theo of his attempts to manage the backlit lighting, "especially figures à contre jour (English against daylight). I have studies of heads, both lit and against the light, and I have worked on the whole figure a number of times, a seamstress, [someone] winding yarn or peeling potatoes. En face and en profil. I do not know whether or not I shall ever finish it, as this is a difficult effect, although I believe I have learned one or two things by it."[31]

The Woman Winding Yarn (F36) portrays a woman sitting close to a window, winding spools of yarn to be woven. Weaving was a historical trade in Nuenen, where Van Gogh lived with his parents in 1884. Van Gogh described the workers as "exceptionally poor folk." The woman in this painting is the mother of the De Groot family who is pouring coffee in The Potato Eaters painting.[32]

-

Woman Sewing, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F71)

-

Peasant Woman Sewing, 1885, Private collection (F126a)

-

Peasant Woman Darning Stockings (b/w copy of a very dark painting), 1885, Private collection (F157)

-

Women Mending Nets in the Dunes, 1882, Private collection (F7)

-

Woman winding yarn, 1884, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F36)

Men

[edit]The basket maker

[edit]As the seasons changed, Van Gogh made paintings of those who worked indoors, like the basket maker.[33] Years after making the paintings, Van Gogh wrote in 1888 of the solitary nature of the occupation: "A weaver or a basket maker often spends whole seasons alone, or almost alone, with his craft as his only distraction. And what makes these people stay in one place is precisely the feeling of being at home, the reassuring and familiar look of things."[34]

-

Peasant Making a Basket, 1885, Musée des Beaux-Arts, La-Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland (F171)

-

Peasant Making a Basket, 1885, Private collection (F171a)

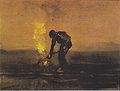

The farm laborer and shepherd

[edit]

Van Gogh had a poetic ideal in painting rural life and dreamed of a time when he might work side-by-side with his brother:

"Theo, be a painter, try to disentangle yourself and come to Drenthe… So boy, do come and paint with me on the heath, in the potato field, come and walk with me behind the plow and the shepherd -- come and sit with me, looking into the fire -- let the storm that blows across the heath blow through you. Break loose from your bonds… Don’t seek [the future] in Paris, don’t seek it in America; it is always the same, forever, and ever exactly the same. Make a thorough change indeed, try the heath.[36]

-

Peasant Burning Weeds 1883 Private collection (F20)

-

Shepherd with a Flock of Sheep (b/w copy of painting), 1884, Soumaya Museum, Tizapán, Mexico (F42)

-

Peasant Digging 1885 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F166)

The sower

[edit]Over Van Gogh's artistic career, he made over 30 works of the sower. He wrote of the symbolism of sowing: "One does not expect to get from life what one has already learned it cannot give; rather, one begins to see more clearly that life is a kind of sowing time, and the harvest is not yet here."[37]

Van Gogh was particularly inspired by Jean-François Millet's work image of the sower and the soulfulness he brought to the works, honoring peasants' agricultural role. Plowing, sowing, and harvesting were seen by Van Gogh as symbols for man's command of nature and its eternal cycles of life.[38]

-

The Sower (study), 1883, Location Unknown (F11)

-

Sower (after Millet), (F830)

-

The Sower, Pencil, brush and ink, 1882, P. und N. de Boer, Amsterdam (F852)

The weaver

[edit]

While living in Nuenen in 1884, Van Gogh made paintings and drawings of weavers over a six-month period.[39] To Van Gogh, the weaver, like the peasant, were considered men who lived a noble life, symbolic of the ongoing cycles of life.[40] Van Gogh was interested in the "meditative appearance" of the weavers.[41] "A weaver who has to direct and to interweave a great many little threads has no time to philosophize about it, but rather he is so absorbed in his work that he doesn't think but acts, and he feels how things must go more than he can explain it." he wrote in 1883.[42]

In the paintings of the weaver, the composition focuses primarily on the loom and the weaver, in nearly iconic imagery. There's a feeling of distance, like someone looking into the scene. It is difficult to discern the weaver's emotion, character or skill.[40] Van Gogh experimented with different mediums and techniques[39] and the effect of light from the window on items in the room using lighter shades of gray.[41]

Rural weaving was not a prosperous trade; income could vary dramatically depending upon crop yields for material and market conditions. Weavers lived a poor life, especially in comparison to urban centers of textile manufacturing such as Leiden, Netherlands. As textile manufacturing was industrialized, the rural artisan's livelihood became increasingly precarious.[39]

Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo, "Their life is hard. A weaver who stays hard at work makes a piece of about 60 yards a week. While he weaves, his wife has to sit before him, winding – in other words, winding the spools of yarn – so there are two of them who work and have to make a living from it."[32]

There are mixed impressions about Van Gogh's weavers. Carl Nordenfolk, art historian, wrote: "Van Gogh presents the weaver as a victim held fast in the spiked jaws of the loom, or a captive in a medieval instrument of torture. The social significance is quite unmistakable. Still, there is one possible explanation: the paintings also possess a tender, intimate atmosphere." A 1969 French text commented that although the depictions are awkward and rigid, "the suite of 'Weavers' is stunning in its presence, its mystery, its brutal force."[40]

In Weaver Facing Left with Spinning Wheel, Van Gogh conveys his feelings for the working poor. The painting is made with somber colors, contrasted against the woven red fabric on the loom.[43]

The Bobbin Winder (F175) wound yarn onto a bobbin for weaving. In this painting, made in the winter of 1883-1884, Van Gogh uses touches of light grey to depict the light falling on the dark room and instrument.[44]

-

Weaver Near an Open Window, 1884, Neue Pinakothek, Munich (F24)

-

Weaver Facing Right (Half-Figure), 1884, Private collection (F26)

-

Weaver, Seen from the Front, 1884, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (F27)

-

Weaver at the Loom, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F30)

-

Weaver Standing in Front of a Loom, 1884, Private collection (F32)

-

Weaver Facing Right also Weaver Standing in Front of the Loom, 1884, Private collection (F33)

-

Loom With Weaver also Weaver Arranging Threads, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F35)

-

Loom With Weaver also Weaver, Interior with Three Small Windows, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F37)

-

Weaver Facing Right (Half-Figure), 1884, Private collection (F162)

-

Loom With Weaver also Weaver at the Loom, drawing, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F1122)

-

Weaver at the Loom, Pencil, pen and ink, 1884, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F1134)

-

Bobbin Winder, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F175)

Man and woman working together

[edit]Peasant Man and Woman Planting Potatoes (F129a) is a spring-planting painting of a man and woman working together. He turns the earth with a spade and she plants the potato seed. The figures of both sit below the horizon, symbolic of their connection to the earth. The painting was made in Nuenen, within the North Brabant district where Van Gogh was raised. Two weeks after completing this painting, Van Gogh completed his best known painting, The Potato Eaters. Potatoes were a staple in the diet of the poor peasants, those who could barely afford bread, and meat was a luxury. Potato was a food not fit for those who could afford better in the 19th century. Thomas Carlyle, a Scottish philosopher, deemed the poor "root-eaters". Van Gogh may have been inspired by the description of Jean-François Millet's biographer, Alfred Sensier of Potato Planting: "one of his [Millet's] most beautiful works" of a married couple "on a wide plain, at the edge of which is a village is lost in the luminous atmosphere; the man opens the ground and the woman drops in the seed potato."[45]

The previous year, Van Gogh painted Potato Planting (F172) which shows a man creating a furrow and the woman dropping the seed potato behind him.[45]

-

Peasant and Peasant Woman Planting Potatoes, 1885, Kunsthaus, Zürich (F129a)

-

Example of Jean-François Millet's work, Potato Planting, c. 1861

-

Potato Planting, 1884, Von der Heydt Museum, Wuppertal, Germany (F172)

Another occupation in which a man and woman often worked together was weaving. The woman would wind yarn into spools while the man worked at the loom creating yards of woven fabric.[32] Women also supported men in the fishing trade by minding their nets. In farm labor, a woman was particularly important, aiding in planting and harvesting. There are many images above of women digging potatoes.

Groups of people

[edit]-

Wood Gatherers in the Snow, 1884, Private collection (F43)

-

Peat Boat with Two Figures, 1883, Drents Museum, Assen, Netherlands (F21)

Gatherings

[edit]-

The Potato Market, watercolor, 1882, Private collection (F1091)

-

The State Lottery also The Poor and Money, 1882, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (F970)

-

A Wood Auction also Lumber Sale, watercolor, 1883, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F1113)

Field Workers

[edit]-

Potato Digging (Five Figures) 1883 Private collection (F9)

-

Farmers Planting Potatoes 1884 Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands (F41)

The Potato Eaters

[edit]

The Potato Eaters (Dutch: De Aardappeleters) is a painting by Van Gogh which he painted in April 1885 while in Nuenen, Netherlands. It is housed in the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. The version at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo is a preliminary oil sketch; he also made a version as a lithograph.

-

The Potato Eaters, 1885, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

-

Study for The Potato Eaters

-

Study for The Potato Eaters, 1885, Private collection (F77r)

-

Study for The Potato Eaters, 1885, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo (F78)

-

Potato Eaters, Lithograph (April 1885), reversed image, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain (F082)

See also

[edit]- Cottages (Van Gogh series)

- Copies by Vincent van Gogh - particularly the "Copies of Millet"

- Early works of Vincent van Gogh

- Houses at Auvers

- Impressionism

- List of works by Vincent van Gogh

- Postimpressionism

- Saint-Paul Asylum, Saint-Rémy (Van Gogh series).

- Thatched Cottages and Houses

References

[edit]- ^ a b c van Gogh, V, van Heugten, S, Pissarro, J, Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. pp. 12, 25. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Jean-François Millet". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 10. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Bargue's Manuals". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Letter 196". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ a b Callow (1990), 116; cites the work of Hulsker.

- ^ a b c Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 96–103

- ^ Callow (1990), 123–124

- ^ "Letter 224". Vincent van Gogh. The Letters. Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum.

- ^ "Still Life with Earthenware and Bottles, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 20. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Black". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ a b Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books. pp. 10, 14, 21, 30.

- ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ "Portrait of Jozef Blok, 1882". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-10' See also "More information", "Exceptional Portrait" on the same page

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "The potato eaters, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Archived from the original on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written July 1885 in Nuenen". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, c. 15-27 April 1882". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-12.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 3 March 1882 in The Hague". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Head of a Woman, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Head of a woman, 1884". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Vincent Van Gogh: Hidden self-portrait discovered by X-ray". BBC News. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "Cottages, 1883". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Head of a Man, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Peasant Woman Cooking by a Fireplace". Collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "The Potato Peeler". Collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2000–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "A Peasant Woman Digging". The Collections. The Barber Institute of Fine Arts. Archived from the original on 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "A Peasant Woman Digging in Front of Her Cottage, c. 1885". Collections. Art Institute of Chicago. 2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Woman Sewing, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ a b c "Woman Winding Yarn, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 3 November 1881 in Etten". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Arles, 24 September 1888". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 44. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ Erickson, K (1998). At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision Of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdsman Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-8028-3856-1.

- ^ Van Gogh, V, van Heugten, S, Pissarro, J, Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ a b c Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 56–60. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

- ^ a b "Series of weavers". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ Harrison, R, ed. (2011). "Vincent van Gogh. Letter to Theo van Gogh. Written 11 March 1883 in The Hague". Van Gogh Letters. WebExhibits. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ^ "Weaver". Collections. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 2011-05-16.

- ^ "Bobbin Winder, 1884". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ^ a b Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 46. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Cottage, 1885". Permanent Collection. Van Gogh Museum. 2005–2011. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

Bibliography

[edit]- Callow, Philip. Vincent van Gogh: A Life, Ivan R. Dee, 1990. ISBN 1-56663-134-3.

- Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity's Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh, 1998. ISBN 0-8028-4978-4.

- Hansen, Nichols, Sund, Knudsen, Bremen (2003). Van Gogh: Fields. Hatje Cantz Publishers for Toledo Museum of Art Exhibition. p. 10. ISBN 3-7757-1131-7.

- Pomerans, Arnold. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 0-14-044674-5

- Tralbaut, Marc Edo. Vincent van Gogh, le mal aimé. Edita, Lausanne (French) & Macmillan, London 1969 (English); reissued by Macmillan, 1974 and by Alpine Fine Art Collections, 1981. ISBN 0-933516-31-2.

- Van Gogh, V, van Heugten, S, Pissarro, J, Stolwijk, C (2008). Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night. Brusells: Mercatorfonds with Van Gogh Museum and Museum of Modern Art. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-87070-736-0.

- van Heugten, Sjraar. Van Gogh The Master Draughtsman. Thames and Hudson, 2005. ISBN 978-0-500-23825-7.

- Wallace, R (1969). The World of Van Gogh (1853-1890). Alexandria, VA, USA: Time-Life Books.

- Zemel, C (1997). Van Gogh's Progress: Utopia, Modernity, and Late-Nineteenth-Century Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08849-2.

External links

[edit]- Van Gogh, paintings and drawings: a special loan exhibition, a fully digitized exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, which contains material on these studies