Sargonid dynasty

| Sargonid dynasty liblibbi Šarru-kīn[a] | |

|---|---|

| Royal family | |

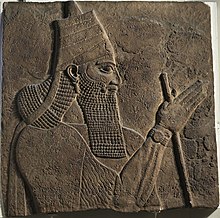

Stele with a depiction of a Sargonid crown prince, c. 704–681 BC, exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art | |

| Parent family | Adaside dynasty (?) |

| Country | Assyria Babylonia |

| Founded | 722 BC |

| Founder | Sargon II |

| Final ruler | Ashur-uballit II |

| Titles | King of Assyria King of Babylon King of the Lands King of Sumer and Akkad King of the Four Corners King of the Universe King of the kings of Egypt and Kush |

| Traditions | Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

| Dissolution | c. 608–606 BC |

| Deposition | 626 BC (Babylonia) 609 BC (Assyria) |

| Periods and dynasties of Babylon |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

|

See also: List of kings by Period and Dynasty |

The Sargonid dynasty was the final ruling dynasty of Assyria, ruling as kings of Assyria during the Neo-Assyrian Empire for just over a century from the ascent of Sargon II in 722 BC to the fall of Assyria in 609 BC. Although Assyria would ultimately fall during their rule, the Sargonid dynasty ruled the country during the apex of its power and Sargon II's three immediate successors Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC), Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian monarchs. Though the dynasty encompasses seven Assyrian kings, two vassal kings in Babylonia and numerous princes and princesses, the term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.

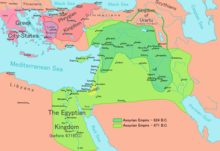

Though the Sargonid dynasty only encompasses the reigns of a few kings, their rule saw the borders of the empire grow to encompass the entire Ancient Near East, the East Mediterranean, Asia Minor, the Caucasus and parts of the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, and they witnessed the subjugation of rivals such as Babylonia, Elam, Persia, Urartu, Lydia, the Medes, Phrygians, Cimmerians, Israel, Judah, Phoenicia, Chaldea, Canaan, the Kushite Empire, the Arabs, and Egypt, as Assyria's rivals were either completely conquered or made vassals.

Following Sargon II's reconquest of Babylon in 710 BC, the Sargonids also periodically ruled as kings of Babylon, though they sometimes preferred to assign vassal kings. Babylon proved to be notoriously difficult to control, with the city and the surrounding lands in southern Mesopotamia repeatedly rebelling against the Sargonid kings despite various different methods being attempted to appease the Babylonians. The final such revolt, by Nabopolassar in 626 BC, succeeded in establishing a new independent kingdom, the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which would less than two decades later destroy the Neo-Assyrian Empire and end the rule of the Sargonid dynasty. The Babylonians allied with the Medes, also rivals of the Assyrians, and though the Medo-Babylonian war against the Assyrian Empire was indecisive at first, the Fall of Nineveh and the death of King Sinsharishkun in 612 BC was a death blow to the Assyrian Empire. Sinsharishkun's successor Ashur-uballit II rallied what remained of the Assyrian army at the city of Harran but lost the city to his enemies in 610–609 BC and was defeated attempting to retake it in 609 BC, ending the rule of the Sargonid dynasty and Assyria's nearly two-millennia long history as an independent political entity.

Background

[edit]

The Sargonid dynasty's century in power was immediately preceded by the reigns of the two kings Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC) and Shalmaneser V (r. 727–722 BC). The nature of Tiglath-Pileser's rise to the throne of Assyria in 745 BC is unclear and disputed.[3] Several pieces of evidence, including that there was a revolt in Nimrud, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, in 746/745 BC,[3][4] that ancient Assyrian sources give conflicting information in regards to Tiglath-Pileser's lineage, and that Tiglath-Pileser in his inscriptions attributes his rise to the throne solely to divine selection rather than both divine selection and his royal ancestry (typically done by Assyrian kings), have been interpreted as indicating that he was a usurper.[3] Though some have gone as far as suggesting that Tiglath-Pileser was not part of the previous royal dynasty, the long-lasting Adaside dynasty, at all,[5] his claims of royal descent were probably true, meaning that regardless of whether he usurped the throne or not, he was a legitimate contender for it.[4]

Though it was chiefly during the Sargonid dynasty that Assyria was transformed from a kingdom primarily based in the Mesopotamian heartland to a truly multinational and multi-ethnic empire, the foundations which allowed this development were laid during Tiglath-Pileser's reign through extensive civil and military reforms. Furthermore, Tiglath-Pileser began a successful series of conquests, subjugating the kingdoms of Babylon and Urartu and conquering the Mediterranean coastline. His successful military innovations, including replacing conscription with levies being supplied from each province, made the Assyrian army one of the most effective armies assembled up until that point.[6]

Tiglath-Pileser's son and successor Shalmaneser V proved to be unpopular due to his poor military and administrative skills and he also seemingly overtaxed the peoples throughout his large empire. After a reign of only five years, Shalmaneser was replaced as king, probably being deposed and assassinated in a palace coup, by the founder of the Sargonid dynasty, Sargon II.[6] Though Sargon II would be connected to previous kings in king lists through a claim that he was the son of Tiglath-Pileser III, this claim is not presented in most of his own inscriptions, where he is also described as being called upon and personally appointed as king by Ashur.[7] Many historians accept Sargon's claim to have been a son of Tiglath-Pileser, but do not believe him to have been the legitimate heir to the throne as the next-in-line after the end of Shalmaneser's reign.[8] Even then, his claim to have been Tiglath-Pileser's son is generally treated with more caution than Tiglath-Pileser's own claims of royal ancestry.[9] Some Assyriologists, such as J. A. Brinkman, believe that Sargon, at the very least, did not belong to the direct dynastic lineage.[10]

Sargon II's rise to the throne saw many rebellions and he might have taken the regnal name Sargon (Šarru-kin in Akkadian, one possible interpretation being "legitimate king") in an effort to portray himself as legitimate.[6] References as late as the 670s BC, during the reign of Sargon II's grandson Esarhaddon, to the possibility that "descendants of former royalty" might try to seize the throne suggests that the Sargonid dynasty was not necessarily well connected to previous Assyrian monarchs.[11] Babylonian king lists dynastically separate Sargon and his descendants from Tiglath-Pileser and Shalmaneser V: Tiglath-Pileser and Shalmaneser are recorded as of the "dynasty of Baltil" (Baltil possibly being the oldest portion of the ancient Assyrian capital of Assur), whereas the Sargonids are recorded as of the "dynasty of Ḫanigalbat", possibly connecting them to an ancient Middle Assyrian junior branch of the Assyrian royal family who governed as viceroys in the western parts of the Assyrian Empire with the title "king of Hanigalbat".[12]

Rulers of the Sargonid dynasty

[edit]Sargon II (722–705 BC)

[edit]

In the aftermath of Sargon II's assumption of the kingship, the political situation throughout the Neo-Assyrian Empire was unstable and volatile. The new king was faced with numerous revolts against his rule and he also had to finish the unfinished final military campaigns of his predecessor Shalmaneser V. Sargon II's quick resolution of Shalmaneser's three-year long siege of Samaria, the capital of the Kingdom of Israel, resulted in the kingdom's fall and the famous loss of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel as nearly 30,000 Israelites were deported and spread out throughout the empire.[13] Though there were uprisings in the Assyrian heartland (as verified by references to "guilty Assyrians" in Sargon II's inscriptions), greater rebellions directed at Sargon II sprung up along the periphery of the empire. A revolt by several of the previously independent kingdoms in the Levant, such as Damascus, Hamath and Arpad, was crushed in 720 BC but an uprising in Babylonia in the south, led by newly proclaimed Babylonian king Marduk-apla-iddina II, successfully defeated Sargon II's attempt at suppressing it, re-establishing Babylonia as an independent kingdom.[14]

With the most directly threatening revolts dealt with and his position consolidated, Sargon II embarked on several campaigns aimed at expanding the borders of the Assyrian Empire. Emulating himself after his ancient namesake, Sargon of Akkad (whom Sargon II probably took his throne name from), Sargon II dreamt of conquering the entire world.[15] In 717 BC, Sargon II conquered the militarily weak but economically strong Kingdom of Carchemish in modern-day Syria, recognized as the successor of the ancient Hittite Empire by its contemporaries, and significantly bolstered the Assyrian treasury.[14] In 714 BC, Sargon II campaigned against Assyria's northern neighbor, Urartu. In order to avoid a series of fortifications alongside Urartu's southern border, Sargon II marched his army around them, through the mountains in modern-day Kermanshah, Iran. Though his troops were exhausted once the Assyrians arrived in Urartian territory, a near-suicidal attack led by just Sargon II and his personal guard against the entire Urartian army rallied his army and Urartu was defeated. Though Sargon II chose not to conquer the entire kingdom due to the exhaustion of his army, he successfully seized and plundered Urartu's holiest city, Musasir.[13]

From 713 BC to the end of his reign, Sargon II constructed a new city, Dur-Sharrukin (meaning 'Sargon's fortress'), which he intended to serve as the new Assyrian capital, though the city was never completely finished, Sargon II moved into the city's palace in 706 BC. In 710 BC, Sargon II and his army marched to reconquer Babylonia. Instead of attacking the south from the north, as he had in his failed attempt a decade earlier, Sargon II marched his army down alongside the eastern bank of the river Tigris and then attacked Babylon from the southeast. Marduk-apla-iddina fled rather than face Sargon II, was later defeated and Sargon II was formally inaugurated as King of Babylon.[13][16] Sargon II's final campaign was against the Kingdom of Tabal in Anatolia, which had thrown off Assyrian control a few years earlier. As in his other campaigns, Sargon II personally led his troops and he died in battle, his body being lost to the enemy.[13][14]

Sennacherib (705–681 BC)

[edit]

Sennacherib ascended to the throne following his father's death in battle, and like most Assyrian kings spent his reign engaging in a series of campaigns and building projects. Sennacherib is most notably remembered for his campaigns against Babylonia and Judah. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, may have been in Nineveh as part of Sennacherib's magnification works on the city as the new royal capital.[17] Sennacherib moved the capital to Nineveh, abandoning Dur-Sharrukin, due to the death of Sargon II in battle being perceived as an ill omen.[13]

Sennacherib's military campaigning began in 703 BC with the king campaigning against Marduk-apla-iddina II of Babylon, Sargon II's old rival, successfully defeating him. Marduk-apla-iddina fled, Babylon was taken once more and the Babylonian palace was plundered, though the citizens were not harmed. A puppet king named Bel-ibni was placed on the throne and for the next two years Babylon was left in peace.[18] In 701 BC, Sennacherib turned from Babylonia to the western part of the empire, where King Hezekiah of Judah had renounced Assyrian allegiance through incitement by Egypt and Marduk-apla-iddina. Various small states in the area which had participated in the rebellion, Sidon and Ashkelon, were taken by force and a string of other cities and states, including Byblos, Ashdod, Ammon, Moab and Edom then paid tribute without resistance. Ekron called on Egypt for help but the Egyptians were defeated. Sennacherib then besieged Hezekiah's capital, Jerusalem, and gave its surrounding towns to Assyrian vassal rulers in Ekron, Gaza and Ashdod. There is no description of how the siege ended, but the annals record a submission by Hezekiah and a list of booty sent from Jerusalem to Nineveh.[19] Hezekiah remained on his throne as a vassal ruler.[18]

Sennacherib placed his eldest son and crown prince Ashur-nadin-shumi on the throne of Babylon in 699 BC.[20] Marduk-apla-iddina continued his rebellion with the help of Elam, and in 694 BC Sennacherib took a fleet of Phoenician ships down the Tigris river to destroy the Elamite base on the shore of the Persian Gulf, but while he was doing this the Elamites captured Ashur-nadin-shumi and put Nergal-ushezib, the son of Marduk-apla-iddina, on the throne of Babylon.[21] Nergal-ushezib was captured in 693 BC and taken to Nineveh, and Sennacherib attacked Elam again. The Elamite king fled to the mountains and Sennacherib plundered his kingdom, but when he withdrew the Elamites returned to Babylon and put another rebel leader, Mushezib-Marduk, on the Babylonian throne. Babylon eventually fell to the Assyrians in 689 BC after a lengthy siege, and Sennacherib dealt with the "Babylonian problem" by utterly destroying the city and even the mound on which it stood by diverting the water of the surrounding canals over the site.[22]

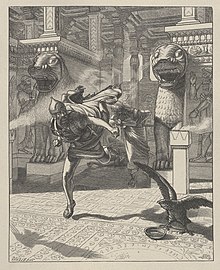

With Ashur-nadin-shumi presumed dead following his abduction by the Elamites, Sennacherib eventually chose to proclaim a younger son, Esarhaddon, as the crown prince rather than Arda-Mulissu who was the next oldest son and had been crown prince for several years following Ashur-nadin-shumi's disappearance.[23] Arda-Mulissu remained a popular and became an increasingly powerful figure in the royal court, attracting support from the aristocrats and scribes. Troubled by this, Sennacherib sent crown prince Esarhaddon to the safety of the western provinces. Arda-Mulissu, feeling that a decisive act would grant him the kingship, made "a treaty of rebellion" with co-conspirators, including another son of Sennacherib, Nabu-shar-usur, and moved to kill his father.[b] Sennacherib was then murdered, either stabbed directly by his son or killed while he was praying by being crushed underneath a statue of a winged bull colossus that guarded the temple, although the former is more likely than the latter.[27] Arda-Mulissu used Sennacherib's destruction of the ancient city of Babylon as a justification for murdering his father.[6]

Esarhaddon (681–669 BC)

[edit]

After Sennacherib's murder, Esarhaddon first had to defeat his brothers Arda-Mulissu and Nabu-shar-usur in six weeks of civil war. Their betrayal deeply affected Esarhaddon, who would remain paranoid and distrustful, particularly of his male relatives, for the rest of his reign.[28][29] Though the brothers who had betrayed him managed to escape, their families, associates and supporters were captured and executed, as was the security staff in the royal palace.[30] To not allow the same justification being used to supplant him as ruler, Esarhaddon quickly moved to rebuild Babylon and issued an official proclamation which made clear that it had been the will of the gods that Babylon be destroyed because the city had lost its respect for the divine. The proclamation makes no mention of Esarhaddon's father but clearly states that Esarhaddon was to be a divinely chosen restorer of the city.[31] Esarhaddon successfully rebuilt the city gates, battlements, drains, courtyards, shrines and various other buildings and structures. Great care was taken during rebuilding of the Esagila (Babylon's great temple), depositing precious stones, scented oils and perfumes into its foundations. Precious metals were chosen to cover the doors of the temple and the pedestal that was to house the Statue of Marduk (the main cult image of Babylon's god, Marduk) was manufactured in gold.[32]

It was due to Esarhaddon's military campaigns that the Neo-Assyrian Empire reached its largest ever extent. He established borders stretching from Nubia in the south-west to the Zagros Mountains in the north-east, including regions such as the Levant, south-eastern Anatolia and all of Mesopotamia. The combination of attentive administration of the government and the successful military campaigns ensured that the empire would remain stable throughout his reign as king and allowed for advances within art, astronomy, architecture, math, medicine and literature.[6] Perhaps his greatest conquest was Egypt, which dramatically increased the size of his empire. After having been defeated in a first failed attempt to conquer the country in 673 BC, Esarhaddon's armies successfully defeated Pharaoh Taharqa in 671 BC after which he captured the Pharaoh's family, including his son and wife, and most of the royal court, which were sent back to Assyria as hostages. Governors loyal to the Assyrian king were then placed in charge of the conquered territories along the Nile.[31]

Not wishing to repeat the bloody transition of power that had begun his own reign, Esarhaddon took steps to ensure that the succession following his own death would be a peaceful one.[6] He designated his eldest living son, Shamash-shum-ukin, as his heir in Babylon and his favored, but younger, son Ashurbanipal as the heir to the Assyrian throne. Although the reasoning behind this is unknown, it is possible that Shamash-shum-ukin's mother was a Babylonian woman, which would have made his eligibility to the Assyrian throne questionable.[33] Esarhaddon's mother Naqi'a issued a treaty commanding the royal court and the various provinces of the empire to accept Esarhaddon's son, Ashurbanipal, as king, and Esarhaddon himself entered into treaties with rival powers, such as the Medians and the Persians, which saw them submit as vassals to Ashurbanipal in advance.[6] After Esarhaddon's death in late 669 BC, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin ascended to their thrones peacefully, proving his succession plans a success.[34]

Ashurbanipal (669–631 BC)

[edit]

After ascending the Assyrian throne and attending the inauguration of his brother Shamash-shum-ukin as the King of Babylon, Ashurbanipal had to immediately deal with Egypt, which had rebelled against Assyrian rule shortly before Esarhaddon's death. The rebellion, led by the same Pharaoh Taharqa that Esarhaddon had defeated in 671 BC was only stopped after Ashurbanipal invaded Egypt c. 667 BC, marching his army as far south as Thebes, sacking several cities in his path and eventually defeating the revolt and appointing Necho I, the former king of Sais, as Egyptian vassal ruler. In 665 BC, Ashurbanipal was forced to war in Egypt again, this time as the country was invaded by Taharqa's designated successor, Tantamani. Although Egypt would be aligned with Assyria for the rest of Assyria's existence, direct control slowly slipped away over the course of Ashurbanipal's reign and by the time of his death, Egypt would be a fully independent kingdom once more, without the need for another revolt.[35]

During the years that followed his Egyptian campaign, Ashurbanipal was kept busy elsewhere. Perhaps the most famous of his many military campaigns were his two wars against Elam, which had long been a thorn in Assyria's side. Though he had successfully defeated Elam in his first campaign in 653 BC,[36] the Elamites rose against Assyria again in 647 BC. Elam's second attack was punished severely by Ashurbanipal, who invaded the country in 647–646 BC, a campaign which saw the brutal plunder and razing of numerous Elamite cities, including the capital Susa. The campaign was thorough; statues of Elamite gods were destroyed, royal tombs were desecrated and the ground was sowed with salt. Ashurbanipal's inscriptions suggest that he had intended to wipe out the Elamites as a distinct cultural group.[37]

Hostility had been building up between Ashurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin throughout their reigns, probably mainly because Ashurbanipal exercised significant control over Shamash-shum-ukin's actions, despite Esarhaddon possibly having intended the two to be equals. When Shamash-shum-ukin openly declared war on his brother in 652 BC, much of southern Mesopotamia followed him in his rebellion.[38] Although Shamash-shum-ukin seemed to initially have the upper hand, successfully securing many allies, his imminent defeat was apparent by 650 BC, when Babylon and many other prominent southern cities were besieged by Ashurbanipal. When Babylon fell to Ashurbanipal's troops in 648 BC, Shamash-shum-ukin is traditionally believed to have committed suicide by setting himself on fire in the palace,[34] but contemporary texts only say that he "met a cruel death" and that the gods "consigned him to a fire and destroyed his life". In addition to suicide though self-immolation or other means, it is possible that he was executed, died accidentally or was killed in some other way.[39]

The end of Ashurbanipal's reign and the beginning of the reign of his son and successor, Ashur-etil-ilani, is shrouded in mystery because of a lack of available sources, but it appears that Ashurbanipal died a natural death in 631 BC.[34][40][41] Although his military activities were impressive, Ashurbanipal is today chiefly remembered because of the Library of Ashurbanipal, the first systematically organized library in the world.[42] The library, composed of more than 30,000 clay tablets containing stories, poems, scientific texts and other writings, was considered by Ashurbanipal himself as his greatest accomplishment.[35] When Assyria fell two decades after Ashurbanipal's death, the library was buried beneath the ruins of Nineveh where many tablets survived undamaged, this being the main reason why many ancient Mesopotamian texts survive to this day.[42][35]

Final kings of Assyria (631–609 BC)

[edit]

Ashur-etil-ilani's brief reign (631–627 BC) was initially met with opposition, as with most successions in Assyria.[44] Although the capital experienced a brief period of unrest and violence, those who conspired against Ashur-etil-ilani were quickly defeated by his rab ša rēši (great/chief eunuch), Sin-shumu-lishir.[40][44] Though few sources remain from Ashur-etil-ilani's reign, Kandalanu continued to serve as vassal king in Babylonia and it appears that Ashur-etil-ilani exercised the same amount of control as his father had.[44] It is possible that he was perceived as a weak ruler; the palaces he constructed were unusually small by Assyrian standards and he is not recorded to have ever gone on a military campaign or a hunting trip, activities who were otherwise common for the Assyrian kings and cemented their position as warrior-kings.[45]

Ashur-etil-ilani's brother Sinsharishkun became king in 627 BC. Although the common idea has been that Sinsharishkun had struggled with his brother and eventually deposed him, there is no evidence to suggest that the succession was violent or that Ashur-etil-ilani's death was unnatural.[46] The rise of a new king might have endangered the general Sin-shumu-lishir's position at the court and Ashur-etil-ilani's old general rebelled, seizing control of northern Babylonia for three months before being defeated.[47] The instability caused by this brief civil war might have been what allowed another general or official, Nabopolassar to revolt in 626 BC.[48]

Sinsharishkun failed to efficiently deal with Nabopolassar's revolt, which led to the foundation of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This new empire allied with the Median Empire to the east and the following Medo-Babylonian war against the Assyrian Empire would have catastrophic effects for Assyria.[49] In 614 BC, the Medes sacked and razed the city of Assur, one of Assyria's previous capitals and still its religious heart and from June to August in 612 BC, the Medes and Babylonians besieged Nineveh. The walls were breached in August, leading to a lengthy and brutal sack, during which Sinsharishkun is assumed to have been killed.[50][51] Sinsharishkun's successor (possibly his son) Ashur-uballit II, rallied what remained of the Assyrian army at the city Harran, where he would be defeated by the Medes and Babylonians in 609 BC, ending the ancient Assyrian monarchy.[52] Ashur-uballit probably died at some point during the following years, c. 608–606 BC.[53]

Although Assyria fell during the rule of the Sargonid dynasty, the Sargonid kings also ruled the country during the apex of its power. Sargon II's three immediate successors; Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, are generally regarded as three of the greatest Assyrian kings.[54] The term Sargonids is sometimes used solely for these three monarchs.[55]

Politics

[edit]Royal iconography

[edit]

Royal iconography, symbols associated with the Assyrian monarchy, in the Sargonid period mostly followed on from trends established during the preceding nearly two millennia of Assyrian monarchy. In the many reliefs by Ashurbanipal, a recurring symbol depicted as embellished on his clothes is a stylized tree (often called a "tree of life" or a "sacred tree") beneath a sun-disc and flanked by a royal figure. Though the exact meaning of the tree is unknown, it likely relates to the divine and had been a symbol associated with the monarchy since the time of Ashurnasirpal II two centuries prior, when it was incorporated into the decorations of the royal palace in Nimrud. Its presence on the clothes of Ashurbanipal suggests that the gods were directly connected to the king, who thus represented the center of the Assyrian realm.[56]

The Sargonid period saw the creation of a definite Assyrian royal emblem, depicted in monumental form on the outside palace walls of the throne rooms of the first three Sargonid kings. This emblem consisted of a hero grasping a lion, flanked on both sides by lamassu (winged human-headed bulls) with their heads turned to the front. Though the emblem is not attested in Ashurbanipal's works, its iconography still appears in some form with frequent depictions of lamassu and lions together with the Assyrian king (a "hero").[57]

A new design element in Ashurbanipal's reliefs was a new open design for the Assyrian royal crown. Though Ashurbanipal is often depicted with the traditional tall and vaguely bucket-shaped crown, especially while depicted in chariots, the new design appears in depictions of informal events, such as lion hunts or scenes of relaxation. The design, depicted as a wide band with a long cloth end hanging pendant at the back, may have served as a more practical alternative during such informal occasions.[56]

Royal women

[edit]

The term used for the queen in the Neo-Assyrian Empire was issi ekalli (or in its abbreviated form, sēgallu), literally meaning "woman of the palace". The feminine form of the title of king (šar or šarru) was šarratu, but this was not used for the consort of the king and was only applied to goddesses and to queens who held sole power in foreign countries.[58][59] As such, this does not indicate that the Assyrian queen would have held a lesser position relative to queens who were consorts to foreign kings.[60] Although Assyrian kings are known to have had multiple wives, surviving inscriptions suggest that there was only one woman with the title of queen at any one given point in time since contemporary documents use the term without further specification.[59]

The kings often showed great and public appreciation for their queens.[61] As an example, Sennacherib discusses his construction of a suite for his wife and queen Tashmetu-sharrat in his new palace at Nineveh in his inscriptions:

And for the queen Tashmetu-sharrat, my beloved wife, whose features Belet-ili has made more beautiful than all other women, I had a palace of love, joy and pleasure built. … By the order of Ashur, father of the gods, and heavenly queen Ishtar may we both live long in health and happiness in this palace and enjoy wellbeing to the full![61]

Sennacherib's second wife Naqi'a, the mother of Esarhaddon, retained a prominent position under Esarhaddon and even under Ashurbanipal, her grandson. She is attested in Ashurbanipal's reign in 663 BC with the title "mother of the king" despite no longer being the mother of the reigning king.[62] Naqi'a is likely to have had residencies in most of the major Assyrian cities and was in her role as queen mother probably extremely wealthy, possibly wealthier than the actual queens of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal. Her influence was increased after Esarhaddon's coronation and she is recorded to have built a palace for him in Nineveh.[63]

The queen was not necessarily the mother of the succeeding king. The queen of Sargon II, Ataliya, was not the mother of his successor Sennacherib and Sennacherib's first wife (it is uncertain of Naqi'a held the title of queen) Tashmetu-sharrat was not the mother of his successor Esarhaddon.[64] Although all female members of the royal family ultimately derived their power from the king (as did all male members of the family), they were not pawns without political power. They had a say in their own financial affairs and had many duties, often in very high levels of the government, in addition to producing an heir.[65] The reign of Esarhaddon has in particular been seen as a time in which the royal women were allowed to exercise great political power, possibly on account of Esarhaddon's mistrust of his male relatives after his brothers had murdered his father and waged civil war in an attempt to usurp the throne from him.[66]

The Babylonian problem

[edit]By the time of the Sargonid kings, Babylonia, the southern part of their empire, had only been incorporated into the Assyrian empire relatively recently. Though an Assyrian vassal for short periods over the course of a few centuries, the kingdom had been ruled by native Babylonian kings until its conquest and annexation by Tiglath-Pileser III less than a century prior.[67] The annexation of Babylonia resulted in what has been termed by historians as the "Babylonian problem", Babylonia's frequent revolts aimed at throwing off Assyria's yoke and re-establishing their independence. Nabopolassar's successful 626 BC revolt, which eventually doomed Assyria, was simply the last in a long line of such Babylonian uprisings.[49]

The Sargonid kings tried many different solutions for the Babylonian problem. Sennacherib, frustrated by Babylon's repeated aspirations of independence, destroyed the city in 689 BC and carried the religiously important Statue of Marduk off into Assyria. The city was then rebuilt by Esarhaddon in the 670s BC, probably in a move that the king hoped would show the benefits of continued Assyrian rule over the region and that he was to rule Babylon with the same care and generosity as a native Babylonian king.[67]

Family tree of the Sargonid dynasty

[edit]Follows Radner (2013) unless otherwise indicated.[68] Kings indicated with bold text, women indicated with italics.

| Ra'ima and Atalia (and other women) | Sargon II r. 722 – 705 BC | Sin-ahu-usur[69] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Son | Son | Tashmetu-sharrat and Naqi'a (and other women) | Sennacherib r. 705 – 681 BC | Son | Son | Ahat-abisha | Ambaris (King of Tabal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ashur-nadin-shumi r. 700 – 694 BC (Babylon) | Ashur-ili-muballissu | Arda-Mulissu | Ashur-shumu-ushabshi | Esharra-hammat (and other women) | Esarhaddon r. 681 – 669 BC | Nergal-shumu-ibni | Nabu-shar-usur | Shadittu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sin-nadin-apli | Shamash-shum-ukin r. 668 – 648 BC (Babylon) | Shamash-metu-uballit | Libbali-sharrat (and other women) | Ashurbanipal r. 669 – 631 BC | Ashur-taqisha-liblut | Ashur-mukin-paleya | Ashur-etel-shame-erseti-muballissu | Sin-peru-ukin | Serua-eterat | At least 9 more children | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ashur-etil-ilani r. 631 – 627 BC | Sinsharishkun r. 627 – 612 BC | Ninurta-sharru-usur | Other sons[44] | At least one daughter[70] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sons[71] | Ashur-uballit II r. 612 – 609 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timeline of Sargonid rulers

[edit]

Notes

[edit]- ^ liblibbi Šarru-kīn means "descendant of Sargon", referring to Sargon II.[1] This genealogical description was used by several members of the dynasty, including Shamash-shum-ukin[1] and Sinsharishkun,[2] in their royal titles.

- ^ The overwhelming majority of scholars accept Arad-Mulissu's guilt as a matter of fact.[24] Other hypotheses have at time been proposed, such as that the crime was committed by some unknown Babylonian sympathizer or even by Esarhaddon himself.[25] In 2020, Andrew Knapp suggested that Esarhaddon might actually have been behind the murder, citing inconsistencies in the account of Arad-Mulissu's guilt, that Esarhaddon might also had a difficult relationship with Sennacherib, the speed in which Esarhaddon assembled an army and defeated his brothers, and other circumstantial evidence.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Karlsson 2017, p. 10.

- ^ Luckenbill 1927, p. 413.

- ^ a b c Davenport 2016, p. 36.

- ^ a b Radner 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Parker 2011, p. 367.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mark 2014b.

- ^ Parker 2011.

- ^ Cogan 2017, p. 154.

- ^ Chen 2020, p. 201.

- ^ Garelli 1991, p. 46.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 63.

- ^ Fales 2014, pp. 204, 227.

- ^ a b c d e Mark 2014c.

- ^ a b c Radner 2012.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Van Der Spek 1977, p. 57.

- ^ Foster & Foster 2009, pp. 121–123.

- ^ a b Grayson 1992, p. 106.

- ^ Grayson 1992, p. 110.

- ^ Grayson 1992, p. 107-108.

- ^ Leick 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Grayson 1992, p. 109.

- ^ Kalimi & Richardson 2014, p. 174.

- ^ Knapp 2020, p. 166.

- ^ Knapp 2020, p. 165.

- ^ Knapp 2020, pp. 167–181.

- ^ Parpola 1980.

- ^ Damrosch 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Knapp 2015, p. 325.

- ^ Radner 2003, p. 166.

- ^ a b Mark 2014a.

- ^ Cole & Machinist 1998, p. 11–13.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 65–66.

- ^ a b c Ahmed 2018, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Mark 2009.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 80.

- ^ Carter & Stolper 1984, p. 52.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 91.

- ^ Zaia 2019, p. 21.

- ^ a b Ahmed 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Reade 1998, p. 263.

- ^ a b Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Da Riva 2017, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Na’aman 1991, p. 255.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 129.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, p. 126.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 13.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 14.

- ^ a b Na’aman 1991, p. 266.

- ^ Lipschits 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Radner 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Radner 2019, p. 141.

- ^ Rowton 1951, p. 128.

- ^ Budge 1880, p. xii.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 3.

- ^ a b Albenda 2014, p. 153.

- ^ Albenda 2014, p. 154.

- ^ Teppo 2007, p. 389.

- ^ a b Kertai 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Kertai 2013, p. 109.

- ^ a b Kertai 2013, p. 116.

- ^ Kertai 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Teppo 2007, p. 391.

- ^ Kertai 2013, p. 121.

- ^ Teppo 2007, p. 392.

- ^ Radner 2003, p. 168.

- ^ a b Porter 1993, p. 41.

- ^ Radner 2013.

- ^ Elayi 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Teppo 2007, p. 388.

- ^ Ahmed 2018, pp. 122–123.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ahmed, Sami Said (2018). Southern Mesopotamia in the time of Ashurbanipal. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3111033587.

- Albenda, Pauline (2014). "Thoughts on some images of King Ashurbanipal". Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires. 4 (98): 153–154.

- Budge, Ernest A. (2007) [1880]. The History of Esarhaddon. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136373213. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- Carter, Elizabeth; Stolper, Matthew W. (1984). Elam: Surveys of Political History and Archaeology. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520099500.

- Chen, Fei (2020). "A List of Assyrian Kings". Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004430921.

- Cogan, Mordechai (2017). "Restoring the Empire". Israel Exploration Journal. 67 (2): 151–167. JSTOR 26740626.

- Cole, Steven W.; Machinist, Peter (1998). Letters From Priests to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal (PDF). Helsinki University Press. ISBN 978-1575063294.

- Damrosch, David (2007). The Buried Book: The Loss and Rediscovery of the Great Epic of Gilgamesh. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805087253.

- Da Riva, Rocío (2017). "The Figure of Nabopolassar in Late Achaemenid and Hellenistic Historiographic Tradition: BM 34793 and CUA 90". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 76 (1): 75–92. doi:10.1086/690464. S2CID 222433095.

- Davenport, T. L. (2016). Situation and Organisation: The Empire Building of Tiglath-Pileser III (745-728 BC) (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Sydney.

- Elayi, Josette (2017). Sargon II, King of Assyria. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1628371772.

- Fales, Frederick Mario (2014). "The Two Dynasties of Assyria". In Gaspa, Salvatore; Greco, Alessandro; Morandi Bonacossi, Daniele; Ponchia, Simonetta; Rollinger, Robert (eds.). From Source to History: Studies on Ancient Near Eastern Worlds and Beyond. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3868351019.

- Foster, Benjamin R.; Foster, Karen Polinger (2009). Civilizations of Ancient Iraq. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691149974.

- Garelli, Paul (1991). "The Achievement of Tiglath-pileser III: Novelty or Continuity?" (PDF). In Cogan, M.; Eph'al, I. (eds.). Studies in Assyrian History and Ancient Near Eastern Historiography Presented to Hayim Tadmor. Jerusalem: Magnes.

- Grayson, A.K. (1992). "Assyria: Sennacherib and Essarhaddon". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Sollberger, E.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5212-2717-9.

- Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (2014). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2017). "Assyrian Royal Titulary in Babylonia". S2CID 6128352.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Knapp, Andrew (2015). Royal Apologetic in the Ancient Near East. SBL Press. ISBN 978-0884140740.

- Kertai, David (2013). "The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Altorientalische Forschungen. 40 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1524/aof.2013.0006. S2CID 163392326.

- Knapp, Andrew (2020). "The Murderer of Sennacherib, yet Again: The Case against Esarhaddon". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 140 (1): 165–181. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.1.0165. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.1.0165. S2CID 219084248.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2009). Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810863248.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volume 2: Historical Records of Assyria From Sargon to the End. University of Chicago Press.

- Na’aman, Nadav (1991). "Chronology and History in the Late Assyrian Empire (631—619 B.C.)". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie. 81 (1–2): 243–267. doi:10.1515/zava.1991.81.1-2.243. S2CID 159785150.

- Parker, Bradley J. (2011). "The Construction and Performance of Kingship in the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Journal of Anthropological Research. 67 (3): 357–386. doi:10.3998/jar.0521004.0067.303. JSTOR 41303323. S2CID 145597598.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1993). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692085.

- Radner, Karen (2003). "The Trials of Esarhaddon: The Conspiracy of 670 BC". ISIMU: Revista sobre Oriente Próximo y Egipto en la antigüedad. 6. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: 165–183.

- Radner, Karen (2016). "Revolts in the Assyrian Empire: Succession Wars, Rebellions Against a False King and Independence Movements". In Collins, John J.; Manning, J. G. (eds.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004330184.

- Radner, Karen (2019). "Last Emperor or Crown Prince Forever? Aššur-uballiṭ II of Assyria according to Archival Sources". State Archives of Assyria Studies. 28: 135–142.

- Reade, J. E. (1998). "Assyrian eponyms, kings and pretenders, 648-605 BC". Orientalia (NOVA Series). 67 (2): 255–265. JSTOR 43076393.

- Rowton, M. B. (1951). "Jeremiah and the Death of Josiah". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 2 (10): 128–130. doi:10.1086/371028. S2CID 162308322.

- Teppo, Saana (2007). "Agency and the Neo-Assyrian Women of the Palace". Studia Orientalia Electronica (101): 381–420.

- Van Der Spek, R. (1977). "The struggle of king Sargon II of Assyria against the Chaldaean Merodach-Baladan (710-707 B.C.)". JEOL. 25: 56–66.

- Zaia, Shana (2019). "My Brother's Keeper: Assurbanipal versus Šamaš-šuma-ukīn" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 6 (1): 19–52. doi:10.1515/janeh-2018-2001. hdl:10138/303983. S2CID 165318561.

Web sources

[edit]- "Ashurbanipal". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2009). "Ashurbanipal". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Esarhaddon". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Sargonid Dynasty". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Mark, Joshua J. (2014). "Sargon II". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Parpola, Simo (1980). "The Murderer of Sennacherib". Gateways to Babylon. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "Sargon II, king of Assyria (721-705 BC)". Assyrian empire builders. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Radner, Karen (2013). "Royal marriage alliances and noble hostages". Assyrian empire builders. Retrieved 26 November 2019.