Sardinian language

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 17,000 words. (June 2023) |

| Sardinian | |

|---|---|

| Sard | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ˈsaɾdu] |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Sardinia |

| Ethnicity | Sardinians |

Native speakers | 1 million (2010, 2016)[1][2][3] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms |

|

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sc |

| ISO 639-2 | srd |

| ISO 639-3 | srd – inclusive code SardinianIndividual codes: sro – Campidanese Sardiniansrc – Logudorese Sardinian |

| Glottolog | sard1257 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-s |

Sardinian is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger[13] | |

Linguistic map of Sardinia. Sardinian is light red (sardu logudoresu dialects) and dark red (sardu campidanesu dialects). | |

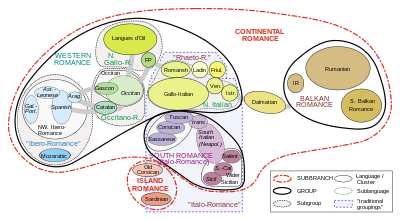

Sardinian or Sard (endonym: sardu [ˈsaɾdu], limba sarda, Logudorese: [ˈlimba ˈzaɾda] Sardinian: [ˈlimba ˈzaɾða] (Nuorese), or lìngua sarda, Campidanese: [ˈliŋɡwa ˈzaɾda]) is a Romance language spoken by the Sardinians on the Western Mediterranean island of Sardinia.

Many Romance linguists consider it, together with Italian, as the language that is the closest to Latin among all Latin's descendants.[14][15][16] However, it has also incorporated elements of Pre-Latin (mostly Paleo-Sardinian and, to a much lesser degree, Punic) substratum,[17] as well as a Byzantine Greek, Catalan, Castilian, and Italian superstratum. These elements originate in the political history of Sardinia, whose indigenous society experienced for centuries competition and at times conflict with a series of colonizing newcomers: before the Middle Ages, the island was for a time a Byzantine possession; then, after a significant period of self-rule with the Judicates, when Sardinian was officially employed in accordance with documentary testimonies, it came during the late Middle Ages into the Iberian sphere of influence, during which Catalan and Castilian became the island's prestige languages and would remain so well into the 18th century. Finally, from the early 18th century onward, under the Savoyard and contemporary Italian one,[18] following the country's linguistic policies which, to the detriment of Sardinian and the local Catalan, led to diglossia.[19]

The original character of the Sardinian language among the Romance idioms has long been known among linguists.[20][21][22][23] After a long strife for the acknowledgement of the island's cultural patrimony, in 1997, Sardinian, along with the other languages spoken therein, managed to be recognized by regional law in Sardinia without challenge by the central government.[5] In 1999, Sardinian and eleven other "historical linguistic minorities", i.e. locally indigenous, and not foreign-grown, minority languages of Italy (minoranze linguistiche storiche, as defined by the legislator) were similarly recognized as such by national law (specifically, Law No. 482/1999).[4][24] Among these, Sardinian is notable as having, in terms of absolute numbers, the largest community of speakers.[25][26][27][28][29][30]

Although the Sardinian-speaking community can be said to share "a high level of linguistic awareness",[31] policies eventually fostering language loss and assimilation have considerably affected Sardinian, whose actual speakers have become noticeably reduced in numbers over the last century.[27] The Sardinian adult population today primarily uses Italian, and less than 15 percent of the younger generations were reported to have been passed down some residual Sardinian,[32][33] usually in a deteriorated form described by linguist Roberto Bolognesi as "an ungrammatical slang".[34]

The rather fragile and precarious state in which the Sardinian language now finds itself, where its use has been discouraged and consequently reduced even within the family sphere, is illustrated by the Euromosaic report, in which Sardinian "is in 43rd place in the ranking of the 50 languages taken into consideration and of which were analysed (a) use in the family, (b) cultural reproduction, (c) use in the community, (d) prestige, (e) use in institutions, (f) use in education".[35]

As the Sardinians have almost been completely assimilated into the Italian national mores, including in terms of onomastics, and therefore now only happen to keep but a scant and fragmentary knowledge of their native and once first spoken language, limited in both scope and frequency of use,[36] Sardinian has been classified by UNESCO as "definitely endangered".[37] In fact, the intergenerational chain of transmission appears to have been broken since at least the 1960s, in such a way that the younger generations, who are predominantly Italian monolinguals, do not identify themselves with the indigenous tongue, which is now reduced to the memory of "little more than the language of their grandparents".[38]

As the long- to even medium-term future of the Sardinian language looks far from secure in the present circumstances,[39] Martin Harris concluded in 2003[40] that, assuming the continuation of present trends to language death, it was possible that there would not be a Sardinian language of which to speak in the future, being referred to by linguists as the mere substratum of the now-prevailing idiom, i.e. Italian articulated in its own Sardinian-influenced variety,[41][42] which may come to wholly supplant the islanders' once living native tongue.

Overview

[edit]Now the question arises as to whether Sardinian is to be considered a dialect or a language. Politically speaking, of course, it is one of the many dialects of Italy, just like the Serbo-Croatian and the Albanian that are spoken in various Calabrian and Sicilian villages. The question, however, takes on a different nature when considered from a linguistic perspective. Sardinian cannot be said to be closely related to any dialect of mainland Italy; it is an archaic Romance tongue with its own distinctive characteristics, which can be seen in its rather unique vocabulary as well as its morphology and syntax, which differ radically from those of the Italian dialects.

As an insular language par excellence, Sardinian is considered the most conservative Romance language, as well as one of the most highly individual within the family;[44][45] its substratum (Paleo-Sardinian or Nuragic) has also been researched. In the first written testimonies, dating to the eleventh century, Sardinian appears as a language already distinct from the dialects of Italy.[46]

A 1949 study by the Italian-American linguist Mario Pei, analyzing the degree to which six Romance languages diverged from Vulgar Latin with respect to their accent vocalization, yielded the following measurements of divergence (with higher percentages indicating greater divergence from the stressed vowels of Vulgar Latin): Sardinian 8%, Italian 12%, Spanish 20%, Romanian 23.5%, Occitan 25%, Portuguese 31%, and French 44%.[47] The study emphasized, however, that it represented only "a very elementary, incomplete and tentative demonstration" of how statistical methods could measure linguistic change, assigned "frankly arbitrary" point values to various types of change, and did not compare languages in the sample with respect to any characteristics or forms of divergence other than stressed vowels, among other caveats.[48]

The significant degree to which the Sardinian language has retained its Latin base was also noted by the French geographer Maurice Le Lannou during a research project on the island in 1941.[49]

Although its lexical base is mostly of Latin origin, Sardinian nonetheless retains a number of traces of the linguistic substratum predating the Roman conquest of the island: several words and especially toponyms stem from Paleo-Sardinian[50] and, to a lesser extent, Phoenician-Punic. These etyma might refer to an early Mediterranean substratum, which reveal close relations with Basque.[51][52][53]

In addition to the aforementioned substratum, linguists such as Max Leopold Wagner and Benvenuto Aronne Terracini trace much of the distinctive Latin character of Sardinia to the languoids once spoken by the Christian and Jewish Berbers in North Africa, known as African Romance.[54] Indeed, Sardinian was perceived as rather similar to African Latin when the latter was still in use, giving credit to the theory that vulgar Latin in both Africa and Sardinia displayed a significant wealth of parallelisms.[55] J. N. Adams is of the opinion that similarities in many words, such as acina ('grape'), pala ('shoulder blade') and spanu(s) ('reddish-brown'), prove that there might have been a fair amount of vocabulary shared between Sardinia and Africa.[56] According to Wagner, it is notable that Sardinian is the only Romance language whose name for the Milky Way ((b)ía de sa báza, (b)ía de sa bálla, 'the Way of Straw') also recurs in the Berber languages.[57]

To most Italians Sardinian is unintelligible, reminding them of Spanish, because of the way in which the language is acoustically articulated;[58] characterized as it is by a sharply outlined physiognomy which is displayed from the earliest sources available, it is in fact considered a distinct language, if not an altogether different branch, among the Romance idioms;[21][59][60][61][62] George Bossong summarises thus: "be this as it may, from a strictly linguistic point of view there can be no doubt that Sardinian is to be classified as an independent Romance language, or even as an independent branch inside the family, and so it is classed alongside the great national languages like French and Italian in all modern manuals of Romance linguistics".[63]

History

[edit]This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 9,600 words. (May 2024) |

Sardinia's relative isolation from mainland Europe encouraged the development of a Romance language that preserves traces of its indigenous, pre-Roman language(s). The language is posited to have substratal influences from Paleo-Sardinian, which some scholars have linked to Basque[64][65] and Etruscan;[66] comparisons have also been drawn with the Berber languages from North Africa[67] to shed more light on the language(s) spoken in Sardinia prior to its Romanization. Subsequent adstratal influences include Catalan, Spanish, and Italian. The situation of the Sardinian language with regard to the politically dominant ones did not change until fascism[68] and, most evidently, the 1950s.[69][70]

Origins of modern Sardinian

[edit]- Prenuragic and Nuragic era

The origins of ancient Sardinian, also known as Paleo-Sardinian, are currently unknown. Research has attempted to discover obscure, indigenous, pre-Romance roots. The root s(a)rd, indicating many place names as well as the island's people, is reportedly either associated with or originating from the Sherden, one of the Sea Peoples.[71] Other sources trace instead the root s(a)rd from Σαρδώ, a legendary woman from the Anatolian Kingdom of Lydia,[72][73] or from the Libyan mythological figure of the Sardus Pater Babai ("Sardinian Father" or "Father of the Sardinians").[74][75][76][77][78][79][80]

In 1984, Massimo Pittau claimed to have found the etymology of many Latin words in the Etruscan language, after comparing it with the Nuragic language(s).[66] Etruscan elements, formerly thought to have originated in Latin, would indicate a connection between the ancient Sardinian culture and the Etruscans. According to Pittau, the Etruscan and Nuragic language(s) are descended from Lydian (and therefore Indo-European) as a consequence of contact with Etruscans and other Tyrrhenians from Sardis as described by Herodotus.[66] Although Pittau suggests that the Tirrenii landed in Sardinia and the Etruscans landed in modern Tuscany, his views are not shared by most Etruscologists.

According to Bertoldi and Terracini, Paleo-Sardinian has similarities with the Iberic languages and Siculian; for example, the suffix -ara in proparoxytones indicated the plural. Terracini proposed the same for suffixes in -/àna/, -/ànna/, -/énna/, -/ònna/ + /r/ + a paragogic vowel (such as the toponym Bunnànnaru). Rohlfs, Butler and Craddock add the suffix -/ini/ (such as the toponym Barùmini) as a unique element of Paleo-Sardinian. Suffixes in /a, e, o, u/ + -rr- found a correspondence in north Africa (Terracini), in Iberia (Blasco Ferrer) and in southern Italy and Gascony (Rohlfs), with a closer relationship to Basque (Wagner and Hubschmid). However, these early links to a Basque precursor have been questioned by some Basque linguists.[81] According to Terracini, suffixes in -/ài/, -/éi/, -/òi/, and -/ùi/ are common to Paleo-Sardinian and northern African languages. Pittau emphasized that this concerns terms originally ending in an accented vowel, with an attached paragogic vowel; the suffix resisted Latinization in some place names, which show a Latin body and a Nuragic suffix. According to Bertoldi, some toponyms ending in -/ài/ and -/asài/ indicated an Anatolian influence. The suffix -/aiko/, widely used in Iberia and possibly of Celtic origin, and the ethnic suffix in -/itanos/ and -/etanos/ (for example, the Sardinian Sulcitanos) have also been noted as Paleo-Sardinian elements (Terracini, Ribezzo, Wagner, Hubschmid and Faust).

Some linguists, like Max Leopold Wagner (1931), Blasco Ferrer (2009, 2010) and Arregi (2017[82]) have attempted to revive a theoretical connection with Basque by linking words such as Sardinian idile 'marshland' and Basque itil 'puddle';[83] Sardinian ospile 'fresh grazing for cattle' and Basque hozpil 'cool, fresh'; Sardinian arrotzeri 'vagabond' and Basque arrotz 'stranger'; Sardinian golostiu and Basque gorosti 'holly'; Gallurese (Corso-Sardinian) zerru 'pig' (with z for [dz]) and Basque zerri (with z for [s]). Genetic data have found the Basques to be close to the Sardinians.[84][85][86]

Since the Neolithic period, some degree of variance across the island's regions is also attested. The Arzachena culture, for instance, suggests a link between the northernmost Sardinian region (Gallura) and southern Corsica that finds further confirmation in the Natural History by Pliny the Elder. There are also some stylistic differences across Northern and Southern Nuragic Sardinia, which may indicate the existence of two other tribal groups (Balares and Ilienses) mentioned by the same Roman author. According to the archeologist Giovanni Ugas,[89] these tribes may have in fact played a role in shaping the current regional linguistic differences of the island.

- Classical period

Around the 10th and 9th century BC, Phoenician merchants were known to have made their presence in Sardinia, which acted as a geographical mediator in between the Iberian and the Italian peninsula. In the eighth and seventh centuries, the Phoenicians began to develop permanent settlements, politically arranged as city-states in similar fashion to the Lebanese coastal areas. It did not take long before they started gravitating around the Carthaginian sphere of influence, whose level of prosperity spurred Carthage to send a series of expeditionary forces to the island; although they were initially repelled by the natives, the North African city vigorously pursued a policy of active imperialism and, by the sixth century, managed to establish its political hegemony and military control over South-Western Sardinia. Punic began to be spoken in the area, and many words entered ancient Sardinian as well.[90] Words like giara 'plateau' (cf. Hebrew yaʿar 'forest, scrub'), g(r)uspinu 'nasturtium' (from Punic cusmin), curma 'fringed rue' (cf. Arabic ḥarmal 'Syrian rue'), mítza 'spring' (cf. Hebrew mitsa, metza 'source, fountainhead'), síntziri 'marsh horsetail' (from Punic zunzur 'common knotgrass'), tzeúrra 'sprout' (from *zerula, diminutive of Punic zeraʿ 'seed'), tzichirìa 'dill' (from Punic sikkíria; cf. Hebrew šēkār 'ale') and tzípiri 'rosemary' (from Punic zibbir) are commonly used, especially in the modern Sardinian varieties of the Campidanese plain, while proceeding northwards the influence is more limited to place names, such as the town of Magomadas, Macumadas in Nuoro or Magumadas in Gesico and Nureci, all of which deriving from the Punic maqom hadash 'new city'.[91][92]

The Roman domination began in 238 BC, but was often contested by the local Sardinian tribes, who had by then acquired a high level of political organization,[93] and would manage to only partly supplant the pre-Latin Sardinian languages, including Punic. Although the colonists and negotiatores (businessmen) of strictly Italic descent would later play a relevant role in introducing and spreading Latin to Sardinia, Romanisation proved slow to take hold among the Sardinian natives,[94] whose proximity to the Carthaginian cultural influence was noted by Roman authors.[95] Punic continued to be spoken well into the 3rd–4th century AD, as attested by votive inscriptions,[96][97] and it is thought that the natives from the most interior areas, led by the tribal chief Hospito, joined their brethren in making the switch to Latin around the 7th century AD, through their conversion to Christianity.[98][note 1] Cicero, who loathed the Sardinians on the ground of numerous factors, such as their outlandish language, their kinship with Carthage and their refusal to engage with Rome,[99] would call the Sardinian rebels latrones mastrucati ('thieves with rough wool cloaks') or Afri ('Africans') to emphasize Roman superiority over a population mocked as the refuse of Carthage.[note 2]

A number of obscure Nuragic roots remained unchanged, and in many cases Latin accepted the local roots (like nur, presumably cognate of Norax, which makes its appearance in nuraghe, Nurra, Nurri and many other toponyms). Barbagia, the mountainous central region of the island, derives its name from the Latin Barbaria (a term meaning 'Land of the Barbarians', similar in origin to the now antiquated word Barbary), because its people refused cultural and linguistic assimilation for a long time: 50% of toponyms of central Sardinia, particularly in the territory of Olzai, are actually not related to any known language.[100] According to Terracini, amongst the regions in Europe that went on to draw their language from Latin, Sardinia has overall preserved the highest proportion of pre-Latin toponyms.[101] Besides the place names, on the island there are still a few names of plants, animals and geological formations directly traceable to the ancient Nuragic era.[102]

By the end of the Roman domination, Latin had gradually become however the speech of most of the island's inhabitants.[103] As a result of this protracted and prolonged process of Romanisation, the modern Sardinian language is today classified as Romance or neo-Latin, with some phonetic features resembling Old Latin. Some linguists assert that modern Sardinian, being part of the Island Romance group,[104] was the first language to split off from Latin,[105] all others evolving from Latin as Continental Romance. In fact, contact with Rome might have ceased from as early as the first century BC.[106] In terms of vocabulary, Sardinian retains an array of peculiar Latin-based forms that are either unfamiliar to, or have altogether disappeared in, the rest of the Romance-speaking world.[107][108]

The number of Latin inscriptions on the island is relatively small and fragmented. Some engraved poems in ancient Greek and Latin (the two most prestigious languages in the Roman Empire[109]) are seen in the so-called "Viper's Cave" (Gruta 'e sa Pibera in Sardinian, Grotta della Vipera in Italian, Cripta Serpentum in Latin), a burial monument built in Caralis (Cagliari) by Lucius Cassius Philippus (a Roman who had been exiled to Sardinia) in remembrance of his dead spouse Atilia Pomptilla;[110] we also have some religious works by Eusebius and Saint Lucifer, both from Caralis and in the writing style of whom may be noted the lexicon and perifrastic forms typical of Sardinian (e.g. narrare in place of dicere; compare with Sardinian nàrrere or nàrri(ri) 'to say').[111]

After a period of 80 years under the Vandals, Sardinia would again be part of the Byzantine Empire under the Exarchate of Africa[112] for almost another five centuries. Luigi Pinelli believes that the Vandal presence had "estranged Sardinia from Europe, linking its own destiny to Africa's territorial expanse" in a bond that was to strengthen further "under Byzantine rule, not only because the Roman Empire included the island in the African Exarchate, but also because it developed from there, albeit indirectly, its ethnic community, causing it to acquire many of the African characteristics" that would allow ethnologists and historians to elaborate the theory of the Paleo-Sardinians' supposed African origin,[113] now disproved. Casula is convinced that the Vandal domination caused a "clear breaking with the Roman-Latin writing tradition or, at the very least, an appreciable bottleneck" so that the subsequent Byzantine government was able to establish "its own operational institutions" in a "territory disputed between the Greek- and the Latin-speaking world".[114]

Despite a period of almost five centuries, the Greek language only lent Sardinian a few ritual and formal expressions using Greek structure and, sometimes, the Greek alphabet.[115][116] Evidence for this is found in the condaghes, the first written documents in Sardinian. From the long Byzantine era there are only a few entries but they already provide a glimpse of the sociolinguistical situation on the island in which, in addition to the community's everyday Neo-Latin language, Greek was also spoken by the ruling classes.[117] Some toponyms, such as Jerzu (thought to derive from the Greek khérsos, 'untilled'), together with the personal names Mikhaleis, Konstantine and Basilis, demonstrate Greek influence.[117]

Judicates period

[edit]

As the Muslims made their way into North Africa, what remained of the Byzantine possession of the Exarchate of Africa was only the Balearic Islands and Sardinia. Pinelli believes that this event constituted a fundamental watershed in the historical course of Sardinia, leading to the definitive severance of those previously close cultural ties between Sardinia and the southern shore of the Mediterranean: any previously held commonality shared between Sardinia and Africa "disappeared, like mist in the sun, as a result of North Africa's conquest by Islamic forces, since the latter, due to the fierce resistance of the Sardinians, were not able to spread to the island, as they had in Africa".[113] Michele Amari, quoted by Pinelli, writes that "the attempts of the Muslims of Africa to conquer Sardinia and Corsica were frustrated by the unconquered valour of the poor and valiant inhabitants of those islands, who saved themselves for two centuries from the yoke of the Arabs".[118]

As the Byzantines were fully focused on reconquering southern Italy and Sicily, which had in the meanwhile also fallen to the Muslims, their attention on Sardinia was neglected and communications broke down with Constantinople; this spurred the former Byzantine province of Sardinia to become progressively more autonomous from the Byzantine oecumene, and eventually attain independence.[119] Pinelli argues that "the Arab conquest of North Africa separated Sardinia from that continent without, however, causing the latter to rejoin Europe" and that this event "determined a capital turning point for Sardinia, giving rise to a de facto independent national government".[113] Historian Marc Bloch believed that, owing to Sardinia being a country which found itself in "quasi-isolation" from the rest of the continent, the earliest documentary testimonies, written in Sardinian, were much older than those first issued in Italy.[120]

Sardinian was the first Romance language of all to gain official status, being used by the four Judicates,[121][122][123][124][note 3] former Byzantine districts that became independent political entities after the Arab expansion in the Mediterranean had cut off any ties left between the island and Byzantium. The exceptionality of the Sardinian situation, which in this sense constitutes a unique case throughout the Latin-speaking Europe, consists in the fact that any official text was written solely in Sardinian from the very beginning and completely excluded Latin, unlike what was happening – and would continue to happen – in France, Italy and Iberia at the same time; Latin, although co-official, was in fact used only in documents concerning external relations in which the Sardinian kings (judikes, 'judges') engaged.[125] Awareness of the dignity of Sardinian for official purposes was such that, in the words of Livio Petrucci, a Neo-Latin language had come to be used "at a time when nothing similar can be observed in the Italian peninsula" not only "in the legal field" but also "in any other field of writing".[126]

A diplomatic analysis of the earliest Sardinian documents shows that the Judicates provided themselves with chanceries, which employed an indigenous diplomatic model for writing public documents;[127] one of them, dating to 1102, displays text in half-uncial, a script that had long fallen out of use on the European continent and F. Casula believes may have been adopted by the Sardinians of Latin culture as their own "national script" from the 8th until the 12th century,[128] prior to their receiving outside influence from the arrival of mainly Italian notaries.

| Extract from Bonarcado's Condaghe,[129] 22 (1120–1146) |

|---|

| "Ego Gregorius, priore de Bonarcadu, partivi cun iudice de Gallulu. Coiuvedi Goantine Mameli, serbu de sancta Maria de Bonarcadu, cun Maria de Lee, ancilla de iudice de Gallul. Fegerunt II fiios: Zipari et Justa. Clesia levait a Zipari et iudice levait a Justa. Testes: Nigola de Pane, Comida Pira, Goantine de Porta, armentariu dessu archipiscobu." |

Old Sardinian had a greater number of archaisms and Latinisms than the present language does, with few Germanic words, mostly coming from Latin itself, and even fewer Arabisms, which had been imported by scribes from Iberia;[130] in spite of their best efforts with a score of expeditions to the island, from which they would get considerable booty and a hefty number of Sardinian slaves, the Arab assailants were in fact each time forcefully driven back and would never manage to conquer and settle on the island.[131]

Although the surviving texts come from such disparate areas as the north and the south of the island, Sardinian then presented itself in a rather homogeneous form:[132] even though the orthographic differences between Logudorese and Campidanese Sardinian were beginning to appear, Wagner found in this period "the original unity of the Sardinian language".[133] In agreement with Wagner is Paolo Merci, who found a "broad uniformity" around this period, as were Antonio Sanna and Ignazio Delogu too, for whom it was the islanders' community life that prevented Sardinian from localism.[132] According to Carlo Tagliavini, these earlier documents show the existence of a Sardinian Koine which pointed to a model based on Logudorese.[134][135]

According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, it was in the wake of the fall of the Judicates of Cagliari and Gallura, in the second half of the 13th century, that Sardinian began to fragment into its modern dialects, undergoing some Tuscanization under the rule of the Republic of Pisa;[136] it did not take long before the Genoese too started carving their own sphere of influence in northern Sardinia, both through the mixed Sardinian-Genoese nobility of Sassari and the members of the Doria family.[137] A certain range of dialectal variation is then noted.[70][2]

A special position was occupied by the Judicate of Arborea, the last Sardinian kingdom to fall to foreign powers, in which a transitional dialect was spoken, that of Middle Sardinian. The Carta de Logu of the Kingdom of Arborea, one of the first constitutions in history drawn up in 1355–1376 by Marianus IV and the Queen, the 'Lady Judge' (judikessa in Sardinian, jutgessa in Catalan, giudicessa in Italian) Eleanor, was written in this transitional variety of Sardinian, and would remain in force until 1827.[138][139] The Arborean judges' effort to unify the Sardinian dialects were due to their desire to be legitimate rulers of the entire island under a single state (republica sardisca 'Sardinian Republic');[140] such political goal, after all, was already manifest in 1164, when the Arborean Judge Barison ordered his great seal to be made with the writings Baresonus Dei Gratia Rei Sardiniee ('Barison, by the grace of God, King of Sardinia') and Est vis Sardorum pariter regnum Populorum ('The people's rule is equal to the Sardinians' own force').[141]

Dante Alighieri wrote in his 1302–05 essay De vulgari eloquentia that Sardinians were strictly speaking not Italians (Latii), even though they appeared superficially similar to them, and they did not speak anything close to a Neo-Latin language of their own (lingua vulgaris), but resorted to aping straightforward Latin instead.[142][143][144][145][146][147][148] Dante's view on the Sardinians, however, is proof of how their language had been following its own course in a way which was already unintelligible to non-islanders, and had become, in Wagner's words, an impenetrable "sphinx" to their judgment.[130] Frequently mentioned is a previous 12th-century poem by the troubadour Raimbaut de Vaqueiras, Domna, tant vos ai preiada ("Lady, so much I have endeared you"); Sardinian epitomizes outlandish speech therein, along with non-Romance languages such as German and Berber, with the troubadour having the lady say "No t'entend plui d'un Todesco / Sardesco o Barbarì" ("I don't understand you more than a German or Sardinian or Berber");[149][150][151][146][152][153][154] the Tuscan poet Fazio degli Uberti refers to the Sardinians in his poem Dittamondo as "una gente che niuno non-la intende / né essi sanno quel ch'altri pispiglia" ("a people that no one is able to understand / nor do they come to a knowledge of what other peoples say about them").[155][148][146]

The Muslim geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi, who lived in Palermo, Sicily at the court of King Roger II, wrote in his work Kitab Nuzhat al-mushtāq fi'khtirāq al-āfāq ('The book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands' or, simply, 'The book of Roger') that "Sardinians are ethnically Rūm Afāriqah, like the Berbers; they shun contacts with all the other Rūm nations and are people of purpose and valiant that never leave the arms".[156][157][158][159][160] According to Wagner, the close relationship in the development of Vulgar Latin between North Africa and Sardinia might not have only derived from ancient ethnic affinities between the two populations, but also from their common political past within the Exarchate of Africa.[161]

What literature is left to us from this period primarily consists of legal and administrative documents, besides the aforementioned Cartas and condaghes. The first document containing Sardinian elements is a 1063 donation to the abbey of Montecassino signed by Barisone I of Torres.[162] Another such document (the so-called Carta Volgare) comes from the Judicate of Cagliari and was issued by Torchitorio I de Lacon-Gunale in around 1070, written in Sardinian whilst still employing the Greek alphabet.[163] Other documents are the 1080 "Logudorese Privilege", the 1089 Torchitorius' Donation (in the Marseille archives), the 1190–1206 Marsellaise Chart (in Campidanese Sardinian) and an 1173 communication between the Bishop Bernardo of Civita and Benedetto, who oversaw the Opera del Duomo in Pisa. The Statutes of Sassari (1316) and Castelgenovese (c. 1334) are written in Logudorese Sardinian.

The first chronicle in lingua sive ydiomate sardo,[164] called Condagues de Sardina, was published anonymously in the 13th century, relating the events of the Judicate of Torres.

Iberian period – Catalan and Castilian influence

[edit]The 1297 feoffment of Sardinia by Pope Boniface VIII led to the creation of the Kingdom of Sardinia: that is, of a state which, although lacking in summa potestas, entered by right as a member in personal union within the broader Mediterranean structure of the Crown of Aragon, a composite state. Thus began a long war between the latter and, to the cry of Helis, Helis, from 1353, the previously allied Judicate of Arborea, in which the Sardinian language was to play the role of an ethnic marker.[165]

The war had, among its motives, a never dormant and ancient Arborean political design to establish "a great island nation-state, wholly indigenous" which was assisted by the massive participation of the rest of the Sardinians, i.e. those not residing within the jurisdiction of Arborea (Sardus de foras),[166] as well as a widespread impatience with the foreign importation of a feudal regime, specifically "more Italie" and "Cathalonie", which threatened the survival of deep-rooted indigenous institutions and, far from ensuring the return of the island to a unitary regime, had only introduced there "tot reges quot sunt ville" ('as many petty rulers as there are villages'),[167] whereas instead "Sardi unum regem se habuisse credebant" ('the Sardinians believed they had one single king').

The conflict between the two sovereign and warring parties, during which the Aragonese possessions making up the Kingdom of Sardinia were first administratively split into two separate "halves" (capita) by Peter IV the Ceremonious in 1355, ended after sixty-seven years with the Iberian victory at Sanluri in 1409 and the renunciation of any succession right signed by William II of Narbonne in 1420. This event marked the definitive end of Sardinian independence, whose historical relevance for the island, likened by Francesco C. Casula to "the end of Aztec Mexico", should be considered "neither triumph nor defeat, but the painful birth of today's Sardinia".[168]

Any outbreak of anti-Aragonese rebellion, such as the revolt of Alghero in 1353, that of Uras in 1470 and finally that of Macomer in 1478, celebrated in De bello et interitu marchionis Oristanei,[169] were and would have been systematically neutralised. From that moment, "quedó de todo punto Sardeña por el rey".[170]

Casula believes that the Aragonese winners from the brutal conflict would then move on to destroy the pre-existing documentary production of the still living Sardinian Judicate, which was predominantly written in Sardinian language along with other ones the chancery was engaged with, leaving behind their trail only "a few stones" and, overall, a "small group of documents",[171] many of which are in fact still preserved and/or refer to archives outside the island.[172] Specifically, the Arborean documents and the palace in which they were kept would be completely set on fire on May 21, 1478, as the viceroy triumphantly entered Oristano after having tamed the aforementioned 1478 rebellion, which threatened the revival of an Arborean identity which had been de jure abolished in 1420 but was still very much alive in popular memory.[173]

Thereafter, the ruling class in Sardinia proceeded to adopt Catalan as their primary language. The situation in Cagliari, a city subject to Aragonese repopulation and where, according to Giovanni Francesco Fara (Ioannes Franciscus Fara / Juanne Frantziscu Fara), for a time Catalan took over Sardinian as in Alghero,[174] was emblematic, so much so as to later generate idioms such as no scit su catalanu ('he does not know Catalan') to indicate a person who could not express themselves "correctly".[175][176] Alghero is still a Catalan-speaking enclave on Sardinia to this day.[176][177] Nevertheless, the Sardinian language did not disappear from official use: the Catalan juridical tradition in the cities coexisted with that of the Sardinians, marked in 1421 by the Parliamentary extension of the Arborean Carta de Logu to the feudal areas during the Reign of King Alfonso the Magnanimous.[178] Fara, in the same first modern monograph dedicated to Sardinia, reported the lively multilingualism in "one and the same people", i.e. the Sardinians, because of immigration "by Spaniards and Italians" who came to the island to trade with the natives.[174]

The long-lasting war and the so-called Black Death had a devastating effect on the island, depopulating large parts of it. People from the neighbouring island of Corsica, which had been already Tuscanised, began to settle en masse in the northern Sardinian coast, leading to the birth of Sassarese and then Gallurese, two Italo-Dalmatian lects.[179][180]

|

Extract from sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de sanctu Gavinu, Prothu et Januariu (A. Cano, ~1400)[181] |

|---|

O |

Despite Catalan being widely spoken and written on the island at this time, leaving a lasting influence in Sardinia, Sardinian continued to be used in documents pertaining to the Kingdom's administrative and ecclesiastical spheres until the late 17th century.[182][183] Religious orders also made use of the language. The regulations of the seminary of Alghero, issued by the bishop Andreas Baccallar on July 12, 1586, were in Sardinian;[184] since they were directed to the entire diocese of Alghero and Unions, the provisions intended for the direct knowledge of the people were written in Sardinian and Catalan.[185] The earliest catechism to date found in lingua sardisca from the post-Tridentine period is dated 1695, at the foot of the synodal constitutions of the archbishopric of Cagliari.[186]

The sociolinguistic situation was characterised by the active and passive competence of the two Iberian languages in the cities and of Sardinian in the rest of the island, as reported in various contemporary testimonies: in 1561, the Portuguese Jesuit Francisco Antonio estimated Sardinian to be «the ordinary language of Sardinia, as Italian is of Italy; in the cities of Cagliari and Alghero the ordinary language is Catalan, although there are many people who also use Sardinian».[187][176] Cristòfor Despuig, in Los Colloquis de la Insigne Ciutat de Tortosa, had previously claimed in 1557 that, although Catalan had carved out a place for itself as llengua cortesana, in many parts of the island the "ancient language of the Kingdom" ("llengua antigua del Regne") was still preserved;[188] the ambassador and visitador reial Martin Carillo (supposed author of the ironic judgment on the Sardinians' tribal and sectarian divisions: "pocos, locos, y mal unidos" 'few, thickheaded, and badly united'[189]) noted in 1611 that the main cities spoke Catalan and Spanish, but outside these cities no other language was understood than Sardinian, which in turn was understood by everyone in the entire Kingdom;[188] Joan Gaspar Roig i Jalpí, author of Llibre dels feyts d'armes de Catalunya, reported in the mid-seventeenth century that in Sardinia "parlen la llengua catalana molt polidament, axì com fos a Catalunya" ('they speak Catalan very well, as though I was in Catalonia');[188] Anselm Adorno, originally from Genoa but living in Bruges, noted in his pilgrimages how, many foreigners notwithstanding, the natives still spoke their own language (linguam propriam sardiniscam loquentes);[190]); another testimony is offered by the rector of the Jesuit college of Sassari Baldassarre Pinyes who, in Rome, wrote: "As far as the Sardinian language is concerned, Your Paternity should know that it is not spoken in this city, nor in Alghero, nor in Cagliari: it is only spoken in the towns".[191]

The 16th century is marked by a new literary revival of Sardinian, starting from the 15th-century Sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de sanctu Gavinu, Brothu et Ianuariu, written by Antòni Canu (1400–1476) and published in 1557.[181] Rimas Spirituales, by Hieronimu Araolla,[192] was aimed at "glorifying and enriching Sardinian, our language" (magnificare et arrichire sa limba nostra sarda) as the Spanish, French and Italian poets had already done for their own languages (la Deffense et illustration de la langue françoyse and Il Dialogo delle lingue). This way, Araolla is one of the first Sardinian authors to bind the language to a Sardinian nation,[193] the existence of which is not outright stated but naturally implied.[194][note 4] Antonio Lo Frasso, a poet born in Alghero[195] (a city he remembered fondly)[196] who spent his life in Barcelona, wrote lyric poetry in Sardinian.[197]

Agreeing with Fara's aforementioned De rebus Sardois, the Sardinian attorney Sigismondo Arquer, author of Sardiniae brevis historia et descriptio in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia universalis (whose report would also be quoted in Conrad Gessner's "On the different languages used by the various nations across the globe" with minor variations[198]), stated that Sardinian prevailed in most of the Kingdom, with particular regard for the interior, while Catalan and Spanish were spoken in the cities, where the predominantly Iberian ruling class "occupies most of the official positions";[176] although the Sardinian language had become fragmented due to foreign domination (i.e. "namely Latins, Pisans, Genoese, Spanish, and Africans"), Arquer pointed to there being many Sardinian words with apparently no traceable origin and reported that Sardinians nevertheless "understand each other perfectly".[199]

Especially through the reorganization of the monarchy led by the Count-Duke of Olivares, Sardinia would gradually join a broad Spanish cultural sphere. Spanish was perceived as an elitist language, gaining solid ground among the ruling Sardinian class; Spanish had thus a profound influence on Sardinian, especially in those words, styles and cultural models owing to the prestigious international role of the Habsburg monarchy as well as the Court.[note 5][192] Most Sardinian authors would write in both Spanish and Sardinian until the 19th century and were well-versed in the former, like Vicente Bacallar y Sanna that was one of the founders of the Real Academia Española;[200] according to Bruno Anatra's estimates, around 87% of the books printed in Cagliari were in Spanish.[189] A notable exception was Pedro Delitala (1550–1590), who decided to write in Italian instead.[195][201] Nonetheless, the Sardinian language retained much of its importance, earning respect from the Spaniards in light of it being the ethnic code the people from most of the Kingdom kept using, especially in the rural areas.[202] Sardinian endured, moreover, in religious drama and the drafting of notarial deeds in the interior.[203] New genres of popular poetry were established around this period, like the gosos or gocius (sacred hymns), the anninnia (lullabies), the atitu (funeral laments), the batorinas (quatrains), the berbos and paraulas (curses), and the improvised poetry of the mutu and mutetu.

Sardinian was also one of the few official languages, along with Spanish, Catalan and Portuguese, whose knowledge was required to be an officer in the Spanish tercios,[204] among which the Sardinians were fully considered and counted as spanyols, as requested by the Stamenti in 1553.[205]

Ioan Matheu Garipa, a priest from Orgosolo who translated the Italian Leggendario delle Sante Vergini e Martiri di Gesù Cristo into Sardinian (Legendariu de Santas Virgines, et Martires de Iesu Christu) in 1627, was the first author to claim that Sardinian was the closest living relative of classical Latin[note 6] and, like Araolla before him,[193] valued Sardinian as the language of a specific ethno-national community.[206] In this regard, the philologist Paolo Maninchedda argues that by doing so, these authors did not write "about Sardinia or in Sardinian to fit into an island system, but to inscribe Sardinia and its language – and with them, themselves – in a European system. Elevating Sardinia to a cultural dignity equal to that of other European countries also meant promoting the Sardinians, and in particular their educated countrymen, who felt that they had no roots and no place in the continental cultural system".[207]

Savoyard period – Italian influence

[edit]The War of the Spanish Succession gave Sardinia to Austria, whose sovereignty was confirmed by the 1713–14 treaties of Utrecht and Rastatt. In 1717 a Spanish fleet reoccupied Cagliari, and the following year Sardinia was ceded to Victor Amadeus II of Savoy in exchange for Sicily. The Savoyard representative, the Count of Lucerna di Campiglione, received the definitive deed of cession from the Austrian delegate Don Giuseppe dei Medici, on condition that the "rights, statutes, privileges of the nation" that had been the subject of diplomatic negotiations were preserved.[209] The island thus entered the Italian orbit after the Iberian one,[210] although this transfer would not initially entail any social nor cultural and linguistic changes: Sardinia would still retain for a long time its Iberian character, so much so that only in 1767 were the Aragonese and Spanish dynastic symbols replaced by the Savoyard cross.[211] Until 1848, the Kingdom of Sardinia would be a composite state, and the island of Sardinia would remain a separate country with its own traditions and institutions, albeit without summa potestas and in personal union as an overseas possession of the House of Savoy.[209]

The Sardinian language, although practiced in a state of diglossia, continued to be spoken by all social classes, its linguistic alterity and independence being universally perceived;[212] Spanish, on the other hand, was the prestige code known and used by the Sardinian social strata with at least some education, in so pervasive a manner that Joaquín Arce refers to it in terms of a paradox: Castilian had become the common language of the islanders by the time they officially ceased to be Spanish and, through their annexation by the House of Savoy, became Italian through Piedmont instead.[213][214][215] Given the current situation, the Piedmontese ruling class which held the reins of the island, in this early phase, resolved to maintain its political and social institutions, while at the same time progressively hollowing them out[216] as well as "treating the [Sardinian] followers of one faction and of the other equally, but keeping them divided in such a way as to prevent them from uniting, and for us to put to good use such rivalry when the occasion presents itself".[217]

According to Amos Cardia, this pragmatic stance was rooted in three political reasons: in the first place, the Savoyards did not want to rouse international suspicion and followed to the letter the rules dictated by the Treaty of London, signed on 2 August 1718, whereby they had committed themselves to respect the fundamental laws of the newly acquired Kingdom; in the second place, they did not want to antagonize the hispanophile locals, especially the elites; and finally, they lingered on hoping they could one day manage to dispose of Sardinia altogether, while still keeping the title of Kings by regaining Sicily.[218] In fact, since imposing Italian would have violated one of the fundamental laws of the Kingdom, which the new rulers swore to observe upon taking on the mantle of King, Victor Amadeus II emphasised the need for the operation to be carried out through incremental steps, small enough to go relatively unnoticed (insensibilmente), as early as 1721.[219] Such prudence was again noted, when the King claimed that he was nevertheless not intentioned to ban either Sardinian or Spanish on two separate occasions, in 1726 and 1728.[220]

The fact that the new masters of Sardinia felt at loss as to how they could better deal with a cultural and linguistic environment they perceived as alien to the Mainland,[221] where Italian had long been the prestige and even official language, can be deduced from the study Memoria dei mezzi che si propongono per introdurre l'uso della lingua italiana in questo Regno ("Account of the proposed ways to introduce the Italian language to this Kingdom") commissioned in 1726 by the Piedmontese administration, to which the Jesuit Antonio Falletti from Barolo responded suggesting the ignotam linguam per notam expōnĕre ("to introduce an unknown language [Italian] through a known one [Spanish]") method as the best course of action for Italianisation.[222] In the same year, Victor Amadeus II had already said he could no longer tolerate the lack of ability to speak Italian on the part of the islanders, in view of the inconveniences that such inability was putting through for the functionaries sent from the Mainland.[223] Restrictions to mixed marriages between Sardinian women and the Piedmontese officers dispatched to the island, which had hitherto been prohibited by law,[224] were at one point lifted and even encouraged so as to better introduce the language to the local population.[225][226]

Eduardo Blasco Ferrer argues that, in contrast to the cultural dynamics long established in the Mainland between Italian and the various Romance dialects thereof, in Sardinia the relationship between the Italian language – recently introduced by Savoy – and the native one had been perceived from the start by the locals, educated and uneducated alike, as a relationship (albeit unequal in terms of political power and prestige) between two very different languages, and not between a language and one of its dialects.[227] The plurisecular Iberian period had also contributed in making the Sardinians feel relatively detached from the Italian language and its cultural sphere; local sensibilities towards the language were further exacerbated by the fact that the Spanish ruling class had long considered Sardinian a distinct language, with respect to their own ones and Italian as well.[228] The perception of the alterity of Sardinian was also widely shared among the Italians who happened to visit the island and recounted their experiences with the local population,[229] whom they often likened to the Spanish and the ancient peoples of the Orient, an opinion illustrated by the Duke Francis IV and Antonio Bresciani;[230][231] a popular assertion by the officer Giulio Bechi, who would participate in a military campaign against Sardinian banditry dubbed as caccia grossa ("great hunt"), was that the islanders spoke "a horrible language, as intricate as Saracen, and sounding like Spanish".[232]

However, the Savoyard government eventually decided to directly introduce Italian altogether to Sardinia on the conventional date of 25 July 1760,[233][234][235][236] because of the Savoyards' geopolitical need to draw the island away from Spain's gravitational pull and culturally integrate Sardinia into the orbit of the Italian peninsula,[237] through the thorough assimilation of the island's cultural models, which were deemed by the Savoyard functionaries as "foreign" and "inferior", to Piedmont.[238][239][240][note 7] In fact, the measure in question prohibited, among other things, "the unreserved use of the Castilian idiom in writing and speaking, which, after forty years of Italian rule, was still so deeply rooted in the hearts of the Sardinian teachers".[241] In 1764, the exclusive imposition of the Italian language was finally extended to all sectors of public life,[242][243][244] including education,[245][246] in parallel with the reorganisation of the Universities of Cagliari and Sassari, which saw the arrival of personnel from the Italian mainland, and the reorganisation of lower education, where it was decided likewise to send teachers from Piedmont to make up for the lack of Italian-speaking Sardinian teachers.[247] In 1763, it had already been planned to "send a number of skilled Italian professors" to Sardinia to "rid the Sardinian teachers of their errors" and "steer them along the right path".[241] The purpose did not elude the attention of the Sardinian ruling class, who deplored the fact that "the Piedmontese bishops have introduced preaching in Italian" and, in an anonymous document attributed to the conservative Sardinian Parliament and eloquently called Lamento del Regno ("Grievance of the Kingdom"), denounced how "the arms, the privileges, the laws, the language, University, and currency of Aragon have now been taken away, to the disgrace of Spain, and to the detriment of all particulars".[188][248]

Spanish was replaced as the official language, even though Italian struggled to take roots for a long time: Milà i Fontanals wrote in 1863 that Catalan had been used in notarial instruments from Sardinia well into the 1780s,[188] together with Sardinian, while parish registers and official deeds continued to be drawn up in Spanish until 1828.[249] The most immediate effect of the order was thus the further marginalization of the Sardinians' native idiom, making way for a thorough Italianisation of the island.[250][251][243][2] For the first time, in fact, even the wealthy and most powerful families of rural Sardinia, the printzipales, started to perceive Sardinian as a handicap.[242] Girolamo Sotgiu asserts on the matter that "the Sardinian ruling class, just as it had become Hispanicized, now became Italianised, without ever managing to become Sardinian, that is to say, to draw from the experience and culture of their people, from which it came, those elements of concreteness without which a culture and a ruling class always seem foreign even in their homeland. This was the objective that the Savoyard government had set itself and which, to a good measure, it managed to pursue".[241]

Francesco Gemelli, in Il Rifiorimento della Sardegna proposto nel miglioramento di sua agricoltura, depicts the island's linguistic pluralism in 1776, and referring to Francesco Cetti's I quadrupedi della Sardegna for a more meticulous analysis of "the character of the Sardinian language ("indole della lingua sarda") and the main differences between Sassarese and Tuscan": "five languages are spoken in Sardinia, that is Spanish, Italian, Sardinian, Algherese, and Sassarese. The former two because of the past and today's domination, and they are understood and spoken through schooling by all the educated people residing in the cities, as well as villages. Sardinian is common to all the Kingdom, and is divided into two main dialects, Campidanese Sardinian and Sardinian from the Upper Half ("capo di sopra"). Algherese is a Catalan dialect, for a Catalan colony is Alghero; and finally Sassarese, which is spoken in Sassari, Tempio and Castel sardo (sic), is a dialect of Tuscan, a relic of their Pisan overlords. Spanish is losing ground to Italian, which has taken over the former in the fields of education and jurisdiction".[252]

The first systematic study on the Sardinian language was written in 1782 by the philologist Matteo Madau, with the title of Il ripulimento della lingua sarda lavorato sopra la sua antologia colle due matrici lingue, la greca e la latina.[253] The intention that motivated Madau was to trace the ideal path through which Sardinian could be elevated to the island's proper national language;[254][255][256] nevertheless, according to Amos Cardia, the Savoyard climate of repression on Sardinian culture would induce Matteo Madau to veil its radical proposals with some literary devices, and the author was eventually unable to ever translate them into reality.[257] The first volume of comparative Sardinian dialectology was produced in 1786 by the Catalan Jesuit Andres Febres, known in Italy and Sardinia by the pseudonym of Bonifacio d'Olmi, who returned from Lima where he had first published a book of Mapuche grammar in 1764.[258] After he moved to Cagliari, he became fascinated with the Sardinian language as well and conducted some research on three specific dialects; the aim of his work, entitled Prima grammatica de' tre dialetti sardi,[259] was to "write down the rules of the Sardinian language" and spur the Sardinians to "cherish the language of their Homeland, as well as Italian". The government in Turin, which had been monitoring Febres' activity, decided that his work would not be allowed to be published: Victor Amadeus III had supposedly not appreciated the fact that the book had a bilingual dedication to him in Italian and Sardinian, a mistake that his successors, while still echoing back to a general concept of "Sardinian ancestral homeland", would from then on avoid, and making exclusive use of Italian to produce their works.[257]

At the end of the 18th century, following the trail of the French Revolution, a group of the Sardinian middle class planned to break away from Savoyard rule and institute an independent Sardinian Republic under French protection; all over the island, a number of political pamphlets printed in Sardinian were illegally distributed, calling for a mass revolt against the "Piedmontese" rule and the barons' abuse. The most famous literary product born out of such political unrest was the poem Su patriottu sardu a sos feudatarios, noted as a testament of the French-inspired democratic and patriotic values, as well as Sardinia's situation under feudalism.[260][261] As for the reactions that the three-year Sardinian revolutionary period aroused in the island's ruling class, who were now in the process of Italianisation, for Sotgiu "its failure was complete: undecided between a breathless municipalism and a dead-end attachment to the Crown, it did not have the courage to lead the revolutionary wave coming from the countryside".[241] In fact, although pamphlets such as "the Achilles of Sardinian Liberation" circulated, denouncing the backwardness of an oppressive feudal system and a Ministry that was said to have "always been the enemy of the Sardinian Nation", and the "social pact between the Sovereign and the Nation" was declared to have been broken, there was no radical change in the form of government: therefore, it is not surprising, according to Sotgiu, that although "the call for the Sardinian nation, its traditions and identity became stronger and stronger, even to the point of requesting the creation of a stable military force of "Sardinian nationals only"", the concrete hypothesis of abolishing the monarchical and feudal regimes did not "make its way into the consciousness of many".[262] The only result was therefore "the defeat of the peasant class emerging from the very core of feudal society, urged on by the masses of peasants and led by the most advanced forces of the Sardinian bourgeoisie"[262] and, conversely, the victory of the feudal barons and "of large strata of the town bourgeoisie that had developed within the framework of the feudal order and feared that the abolition of feudalism and the proclamation of the Republic might simultaneously destroy the very basis of their own wealth and prestige".[263]

In the climate of monarchic restoration that followed Giovanni Maria Angioy's rebellion, whose substantial failure marked therefrom a historic watershed in Sardinia's future,[263] other Sardinian intellectuals, all characterized by an attitude of general devotion to their island as well as proven loyalty to the House of Savoy, posed in fact the question of the Sardinian language, while being careful enough to use only Italian as a language to get their point across. During the 19th century in particular, the Sardinian intellectuality and ruling class found itself divided over the adherence to the Sardinian national values and the allegiance to the new Italian nationality,[264] toward which they eventually leaned in the wake of the abortive Sardinian revolution.[265] The identity crisis of the Sardinian ruling class, and their strive for acceptance into the new citizenship of the Italian identity, would manifest itself with the publication of the so-called Falsi d'Arborea[266] by the unionist Pietro Martini in 1863.

A few years after the major anti-Piedmontese revolt, in 1811, the priest Vincenzo Raimondo Porru published a timid essay of Sardinian grammar, which, however, referred expressively to the Southern dialect (hence the title of Saggio di grammatica del dialetto sardo meridionale[267]) and, out of prudence towards the king, was made with the declared intention of easing the acquisition of Italian among his fellow Sardinians, instead of protecting their language.[268] The more ambitious work of the professor and senator Giovanni Spano, the Ortographia sarda nationale ("Sardinian National Orthography"),[269] although it was officially meant for the same purpose as Porru's,[note 8] attempted in reality to establish a unified Sardinian orthography based on Logudorese, just like Florentine had become the basis for Italian.[270][271]

The jurist Carlo Baudi di Vesme claimed that the suppression of Sardinian and the imposition of Italian was desirable to make the islanders into "civilized Italians".[note 9][272] Since Sardinia was, in the words of Di Vesme, "not Spanish, but neither Italian: it is and has been for centuries just Sardinian",[273] it was necessary, at the turn of the circumstances that "inflamed it with ambition, desire and love of all things Italian",[273] to promote these tendencies even more in order "to profit from them in the common interest",[273] for which it proved "almost necessary"[274] to spread the Italian language in Sardinia "presently so little known in the interior"[273] with a view to better enable the Perfect Fusion: "Sardinia will be Piedmont, it will be Italy; it will receive and give us lustre, wealth and power!".[275][276]

The primary and tertiary education was thus offered exclusively through Italian, and Piedmontese cartographers went on to replace many Sardinian place names with Italian ones.[243] The Italian education, being imparted in a language the Sardinians were not familiar with,[note 10] spread Italian for the first time in history to Sardinian villages, marking the troubled transition to the new dominant language; the school environment, which employed Italian as the sole means of communication, grew to become a microcosm around the then-monolingual Sardinian villages.[note 11] In 1811, the canon Salvatore Carboni published in Bologna the polemic book Sos discursos sacros in limba sarda ("Holy Discourses in Sardinian language"), wherein the author lamented the fact that Sardinia, "hoe provinzia italiana non podet tenner sas lezzes e sos attos pubblicos in sa propia limba" ("Being an Italian province nowadays, [Sardinia] cannot have laws and public acts made in its own language"), and while claiming that "sa limba sarda, totu chi non uffiziale, durat in su Populu Sardu cantu durat sa Sardigna" ("the Sardinian language, however unofficial, will last as long as Sardinia among the Sardinians"), he also asked himself "Proite mai nos hamus a dispreziare cun d'unu totale abbandonu sa limba sarda, antiga et nobile cantu s'italiana, sa franzesa et s'ispagnola?" ("Why should we show neglect and contempt for Sardinian, which is a language as ancient and noble as Italian, French and Spanish?").[277]

In 1827, the historical legal code serving as the consuetud de la nació sardesca in the days of the Iberian rule, the Carta de Logu, was abolished and replaced by the more advanced Savoyard code of Charles Felix "Leggi civili e criminali del Regno di Sardegna", written in Italian.[278][279] The Perfect Fusion with the Mainland States, enacted under the auspices of a "transplant, without any reserves and obstacles, [of] the culture and civilization of the Italian Mainland to Sardinia",[280] would result in the loss of the island's residual autonomy[281][278] and marked the moment when "the language of the "Sardinian nation" lost its value as an instrument with which to ethnically identify a particular people and its culture, to be codified and cherished, and became instead one of the many regional dialects subordinated to the national language".[282]

Despite the long-term assimilation policy, the anthem of the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia would be S'hymnu sardu nationale ("the Sardinian National Anthem"), also known as Cunservet Deus su Re ("God save the King"), before it was de facto replaced by the Italian Marcia Reale as well, in 1861.[283] However, even when the island became part of the Kingdom of Italy under Victor Emmanuel II in 1861, Sardinia's distinct culture from the now unified Mainland made it an overall neglected province within the newly proclaimed unitary nation state.[284] Between 1848 and 1861, the island was plunged into a social and economic crisis that was to last until the post-war period.[285] Eventually, Sardinian came to be perceived as sa limba de su famine / sa lingua de su famini, literally translating into English as "the language of hunger" (i.e. the language of the poor), and Sardinian parents strongly supported the teaching of the Italian tongue to their children, since they saw it as the portal to escaping from a poverty-stricken, rural, isolated and underprivileged life.

Late modern period

[edit]

At the dawn of the 20th century, Sardinian had remained an object of research almost only among the island's scholars, struggling to garner international interest and even more suffering from a certain marginalization in the strictly Italian sphere: one observes in fact "the prevalence of foreign scholars over Italian ones and/or the existence of fundamental and still irreplaceable contributions by non-Italian linguists".[286] Previously, Sardinian had been mentioned in a book by August Fuchs on irregular verbs in Romance languages (Über die sogennannten unregelmässigen Zeitwörter in den romanischen Sprachen, Berlin, 1840) and, later, in the second edition of Grammatik der romanischen Sprachen (1856–1860) written by Friedrich Christian Diez, credited as one of the founders of Romance philology.[286] The pioneering research of German authors spurred a certain interest in the Sardinian language on the part of some Italian scholars, such as Graziadio Isaia Ascoli and, above all, his disciple Pier Enea Guarnerio, who was the first in Italy to classify Sardinian as a separate member of the Romance language family without subordinating it to the group of "Italian dialects", as was previously the custom in Italy.[287] Wilhelm Meyer-Lübke, an undisputed authority on Romance linguistics, published in 1902 an essay on Logudorese Sardinian from the survey of the condaghe of San Pietro di Silki (Zur Kenntnis des Altlogudoresischen, in Sitzungsberichte der kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaft Wien, Phil. Hist. Kl., 145), the study of which led to the initiation into Sardinian linguistics of the then university student Max Leopold Wagner: it is to the latter's activity that much of the twentieth-century knowledge and research of Sardinian in the phonetic, morphological and, in part, syntactic fields was generated.[287]

During the mobilization for World War I, the Italian Army compelled all people on the island that were "of Sardinian stock" (di stirpe sarda[288]) to enlist as Italian subjects and established the Sassari Infantry Brigade on 1 March 1915 at Tempio Pausania and Sinnai. Unlike the other infantry brigades of Italy, Sassari's conscripts were only Sardinians (including many officers). It is currently the only unit in Italy with an anthem in a language other than Italian: Dimonios ("Devils"), which would be written in 1994 by Luciano Sechi; its title derives from the German-language Rote Teufel ("red devils"), by which they were popularly known among the troops of the Austro-Hungarian Army. Compulsory military service around this period played a role in language shift and is referred to by historian Manlio Brigaglia as "the first great mass "nationalization"" of the Sardinians.[289] Nevertheless, similarly to Navajo-speaking service members in the United States during World War II, as well as Quechua speakers during the Falklands War,[290] native Sardinians were offered the opportunity to be recruited as code talkers to transmit tactical information in Sardinian over radio communications which might have otherwise run the risk of being gained by Austrian troops, since some of them hailed from Italian-speaking areas to which, therefore, the Sardinian language was utterly alien:[291] Alfredo Graziani writes in his war diary that "having learned that many of our phonograms were being intercepted, we adopted the system of communicating on the phone only in Sardinian, certain that in this way they would never be able to understand what one was saying".[292] To avoid infiltration attempts by said Italophone troops, positions were guarded by Sardinian recruits from the Sassari Brigade who required anyone who came to them that they identify themselves first by proving they spoke Sardinian: "si ses italianu, faedda in sardu!".[293][294][291]

The Sardinian-born philosopher Antonio Gramsci commented on the Sardinian linguistic question while writing a letter to his sister Teresina; Gramsci was aware of the long-term ramifications of language shift, and suggested that Teresa let her son acquire Sardinian with no restriction, because doing otherwise would result in "putting his imagination into a straitjacket" as well as him ending up eventually "learning two jargons, and no language at all".[295][296][297]

Coinciding with the year of the Irish War of Independence, Sardinian autonomism re-emerged as an expression of the fighters' movement, coagulating into the Sardinian Action Party (PsdAz) which, before long, would become one of the most important players in the island's political life. At the beginning, the party would not have had strictly ethnic claims though, being the Sardinian language and culture widely perceived, in the words of Fiorenzo Toso, as "symbols of the region's underdevelopment".[285]

The policy of forced assimilation culminated in the twenty years of the Fascist regime, which launched a campaign of violent repression of autonomist demands and finally determined the island's definitive entry into the "national cultural system" through the combined work of the educational system and the one-party system.[298] Local cultural expressions were thus repressed, including Sardinia's festivals[299] and improvised poetry competitions,[300][301][302][303][304] and a large number of Sardinian surnames were changed to sound more Italian. An argument broke out between the Sardinian poet Antioco Casula (popularly known as Montanaru) and the fascist journalist Gino Anchisi, who stated that "once the region is moribund or dead", which the regime declared to be,[note 12] "so will the dialect (sic)", which was interpreted as "the region's revealing spiritual element";[305] in the wake of this debate, Anchisi managed to have Sardinian banned from the printing press, as well.[306][307] The significance of the Sardinian language as it was posed by Casula, in fact, lent itself to potentially subversive themes, being tied to the practices of cultural resistance of an indigenous ethnic group,[308] whose linguistic repertoire had to be introduced in school to preserve a "Sardinian personality" and regain "a dignity" perceived to have been lost in the process.[309] Another famed poet from the island, Salvatore (Bore) Poddighe, fell into a severe depression and took his own life a few years after his masterwork (Sa Mundana Cummedia[310]) had been seized by Cagliari's police commissioner.[311] When the use of Sardinian in school was banned in 1934 as part of a nation-wide educational plan against the alloglot "dialects", the then Sardinian-speaking children were confronted with another means of communication that was supposed to be their own from then onwards.[312]

On a whole, this period saw the most aggressive cultural assimilation effort by the central government,[313] which led to an even further sociolinguistic degradation of Sardinian.[314] While the interior managed to at least partially resist this intrusion at first, everywhere else the regime had succeeded in thoroughly supplanting the local cultural models with new ones hitherto foreign to the community and compress the former into a "pure matter of folklore", marking a severance from the island's heritage that engendered, according to Guido Melis, "an identity crisis with worrying social repercussions", as well as "a rift that could no longer be healed through the generations".[315] This period is identified by Manlio Brigaglia as the second mass "nationalization" of the Sardinians, which was characterized by "a policy deliberately aiming at "Italianisation"" by means of, in his words, "a declared war" against the usage of the Sardinian language by fascism and the Catholic Church alike.[289]

In 1945, following the restoration of political freedoms, the Sardinian Action Party called for autonomy as a federal state within the "new Italy" that had emerged from the Resistance:[285] it was in the context of the second post-war period that, as consensus for autonomy kept growing, the party began to distinguish itself by policies based on Sardinia's linguistic and cultural specificity.[285]

Present situation

[edit]

After World War II, awareness around the Sardinian language and the danger of its slipping away did not seem to concern the Sardinian elites and entered the political spaces later than in other European peripheries marked by the presence of local ethno-linguistic minorities;[316] Sardinian was in fact dismissed by the middle class,[314] as both the Sardinian language and culture were still being held responsible for the island's underdevelopment.[281] The Sardinian ruling class, drawn to the Italian modernisation stance on how to steer the islanders to "social development", believed in fact that the Sardinians had been held back by their own "traditional practices" vis-à-vis the mainlanders, and that, in order to catch up with the latter, social and cultural progress could only be brought about through the rejection of said practices.[317][318] As the language bore an increasing amount of stigmatisation and came to be perceived as an undesirable identity marker, the Sardinians were consequently encouraged to part with it by way of linguistic and cultural assimilation.[319]

At the time of drafting of the statute in 1948, the national legislator in Rome eventually decided to specify the "Sardinian specialty" as a criterion for political autonomy uniquely on the grounds of local socio-economic issues; further considerations were discarded which were centred on the ascertainment of a distinct cultural, historical and geographical identity, although they had been hitherto the primary local justifications arguing for home rule,[320][321][322][323][324][325] as they were looked down upon as a potential prelude to more autonomist or even more radical separatist claims;[326] this view would be exemplified by a report of the Italian Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry into Banditry, which warned against a looming threat posed by "isolationist tendencies injurious to the development of Sardinian society and recently manifesting themselves in the proposal to regard Sardinian as the language of an ethnic minority".[327] Eventually, the special statute of 1948 settled instead to concentrate on the arrangement of state-funded plans (baptised with the Italian name of piani di rinascita) for the heavy industrial development of the island.[328]

Therefore, far from generating a Statute grounded on the acknowledgment of a particular cultural identity like, for example, in the Aosta Valley and South Tyrol, what ended up resulting in Sardinia was, in the words of Mariarosa Cardia, an outcome "solely based on economic considerations, because there was not either the will or the ability to devise a strong and culturally motivated autonomy, a "Sardinian specificity" that was not defined in terms of social backwardness and economic deprivation".[329] Emilio Lussu, who admitted that he had only voted in favour of the final draft "to prevent the Statute from being rejected altogether by a single vote, even in such a reduced form", was the only member, at the session of 30 December 1946, to call in vain for the mandatory teaching of the Sardinian language, arguing that it was "a millenary heritage that must be preserved".[330]

In the meantime, the emphasis on Italian continued,[2] with historical sites and ordinary objects being henceforth popularised in Italian for mass consumption (e.g. the various kinds of "traditional" pecorino cheese, zippole instead of tzipulas, carta da musica instead of carasau, formaggelle instead of pardulas / casadinas, etc.).[331] The Ministry of Public Education once requested that the teachers willing to teach Sardinian be put under surveillance.[332][333][334] The rejection of the indigenous language and culture, along with a rigid model of Italian-language education[335] which induced a denigration of Sardinian through corporal punishment and shaming,[336][337] has led to poor schooling for the Sardinians.[338][339][340] Roberto Bolognesi stated that in his school years in Sardinia, he had "witnessed both physical and psychological abuse against monolingual Sardinian-speaking children. The psychological violence consisted usually in calling the children "donkeys" and in inviting the whole class to join the mockery".[341] Early school leaving and high school failure rates in Sardinia prompted a debate in the early Nineties on the efficaciousness of strictly monolingual education, with proposals for a focus on a comparative approach.[342]