Rojava conflict

| Rojava conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Syrian civil war and the Turkish–Kurdish conflict | |||||||||

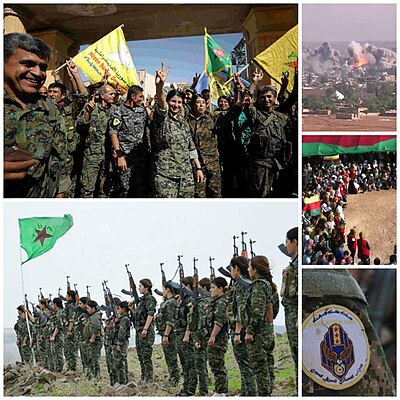

Top left: SDF Victory in the Battle for Raqqa (2017). Top right: Coalition airstrike on ISIL position in Kobanî. Middle right: PYD supporters at a funeral. Bottom left: Kurdish YPJ fighters. Bottom right: Syriac Military Council patch. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Syrian opposition |

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Arab tribesmen

|

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| 478 civilians killed by SDF, [13] | |||||||||

The Rojava conflict, also known as the Rojava Revolution, is a political upheaval and military conflict taking place in northern Syria, known among Kurds as Western Kurdistan or Rojava.

During the Syrian civil war that began in 2011, a Kurdish-dominated coalition led by the Democratic Union Party as well as some other Kurdish, Arab, Syriac-Assyrian, and Turkmen groups have sought to establish a new constitution for the de facto autonomous region, while military wings and allied militias have fought to maintain control of the region. This led to the establishment of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) in 2016.[20]

Supporters of the AANES state that the events constitute a social revolution[21] with a prominent role played by women both on the battlefield and within the newly formed political system, as well as the implementation of democratic confederalism, a form of libertarian socialism that emphasizes decentralization, gender equality and the need for local governance through direct democracy.[6][21]

Background

State discrimination

Repression of the Kurds and other ethnic minorities has gone on since the creation of the French Mandate of Syria after the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement.[22] The Syrian government (officially known as the Syrian Arab Republic) never officially acknowledged the existence of the Kurds[22] and in 1962, 120,000 Syrian Kurds were stripped of their citizenship, leaving them stateless.[23] The Kurdish language and culture have also been suppressed. The government attempted to resolve these issues in 2011 by granting all Kurds citizenship, but only an estimated 6,000 out of 150,000 stateless Kurds have been given nationality and most discriminatory regulations, including the ban on teaching Kurdish, are still on the books.[24] Due to the Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011, the government is no longer in a position to enforce these laws.

Qamishli uprising

In 2004, riots broke out against the government in the northeastern city of Qamishli. During a soccer match between a local Kurdish team and a visiting Arab team from Deir ez-Zor, some Arab fans brandished portraits of Saddam Hussein, who killed tens of thousands of Kurds in Southern Kurdistan during the Al-Anfal campaign in the 1980s. Tensions quickly escalated into open protests, with Kurds raising their flag and taking to the streets to demand cultural and political rights. Security forces fired into the crowd, killing six Kurds, including three children. Protesters went on to burn down the Ba'ath Party's local office. At least 30 and as many as 100 Kurds were killed by the government before the protests were quelled. Thousands of Kurds then fled to Iraq, where a refugee camp was established. Occasional clashes between Kurdish protesters and government forces occurred in the following years.[25][26]

Mashouq al-Khaznawi, a very influential Kurdish sheikh, was killed in 2005 due to his increasing activism which began during the 2004 Qamishli uprisings. He was described as the "center" of the 2004 uprisings and was considered a threat by the Syrian government, who killed him and sparked outrage among Kurds.[27]

The path to self-governed Rojava

Syrian Civil War

In 2011, the Arab Spring spread to Syria. In an echo of the Tunisian revolution, Syrian citizen Hasan Ali Akleh soaked himself in gasoline and set himself on fire in the northern city of Al-Hasakah. This inspired activists to call for a "Day of Rage", which was sparsely attended, mostly because of fear of repression from the Syrian government. Days later, however, protests again took place, this time in response to the police beating of a shopkeeper.[28]

Smaller protests continued, and on 7 March 2011, thirteen political prisoners went on hunger strike, and momentum began to grow against the Assad government. Three days later dozens of Syrian Kurds went on hunger strike in solidarity.[29] On 12 March, major protests took place in Qamishli and Al-Hasakah to both protest the Assad government and commemorate Kurdish Martyrs Day.[30]

Protests grew over the months of March and April 2011. The Assad government attempted to appease Kurds by promising to grant citizenship to thousands of Kurds, who until that time had been stripped of any legal status.[31] By the summer, protests had only intensified, as did violent crackdowns by the Syrian government.

In August, a coalition of opposition groups formed the Syrian National Council in hopes of creating a democratic, pluralistic alternative to the Assad government. But internal fighting and disagreement over politics and inclusion plagued the group from its beginnings. In the fall of 2011 the popular uprising escalated to an armed conflict. The Free Syrian Army (FSA) began to coalesce and armed insurrection spread, largely across central and southern Syria.[32]

Kurdish parties negotiate

The National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, a coalition of Syria's 12 Kurdish parties, boycotted a Syrian opposition summit in Antalya, Turkey on 31 May 2011, stating that "any such meeting held in Turkey can only be a detriment to the Kurds in Syria, because Turkey is against the aspirations of the Kurds".[33]

During the August summit in Istanbul, which led to the creation of the Syrian National Council, only two of the parties in the National Movement of Kurdish Parties in Syria, the Kurdish Union Party and the Kurdish Freedom Party, attended the summit.[34]

Anti-government protests had been ongoing in the Kurdish-inhabited areas of Syria since March 2011, as part of the wider Syrian uprising, but clashes started after the opposition Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and Kurdish National Council (KNC) signed a seven-point agreement on 11 June 2012 in Erbil under the auspice of Iraqi Kurdistan president Massoud Barzani. This agreement, however, failed to be implemented and so a new cooperation agreement between the two sides was signed on 12 July which saw the creation of the Kurdish Supreme Committee as a governing body of all Kurdish-controlled territories in Syria.[35][36][37]

YPG claims territory

The People's Protection Units (YPG) entered the conflict by capturing the city of Kobanî on 19 July 2012, followed by the capture of Amuda and Efrîn on 20 July.[38] The cities fell without any major clashes, as Syrian security forces withdrew without any significant resistance.[38] The Syrian Army pulled out to fight elsewhere.[39] The KNC and PYD then formed a joint leadership council to run the captured cities.

|

|---|

The YPG forces continued with their advancement and on 21 July captured Al-Malikiyah (Kurdish: Dêrika Hemko), which lies 10 kilometers from the Turkish border.[40] The forces at the time also intended to capture Qamishli, the largest Syrian city with a Kurdish majority.[41] On the same day, the Syrian government attacked a patrol of Kurdish YPG members and wounded one fighter.[42] The next day it was reported that Kurdish forces were still fighting for Al-Malikiyah, where one young Kurdish activist was killed after government security forces opened fire on protesters. The YPG also took control over the towns of Ra's al-'Ayn (Kurdish: Serê Kaniyê) and Al-Darbasiyah (Kurdish: Dirbêsiyê), after the security and political units withdrew from these areas, following an ultimatum issued by the Kurds. On the same day, clashes erupted in Qamishli between YPG and government forces in which one Kurdish fighter was killed and two were wounded along with one government official.[43]

On 24 July, the PYD announced that Syrian security forces had withdrawn from the small Kurdish city of 16,000 of Al-Ma'bada (Kurdish: Girkê Legê), between Al-Malikiyah and the Turkish borders. The YPG forces then took control of all government institutions.[44]

Self-governed Rojava established

On 1 August 2012, state security forces on the periphery of the country were pulled into the intensifying battle taking place in Aleppo. During this large withdrawal from the north, the YPG took control of at least parts of Qamishli, Efrin, Amude, Dirbesiye and Kobanî with very little conflict or casualties.[45]

On 2 August 2012, the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change announced that most Kurdish-majority cities in Syria, except Qamishli and Hasaka, were no longer controlled by government forces and were now being governed by Kurdish political parties.[46] In Qamishli, government military and police forces remained in their barracks and administration officials in the city allowed the Kurdish flag to be raised.[47]

After months of de facto rule, the PYD officially announced its regional autonomy on 9 January 2014. Elections were held, popular assemblies established and the Constitution of Rojava was approved. Since then, residents organized local assemblies, reopened schools, established community centers, and helped push back the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) to gain control of almost all land in Syria east of the Euphrates river. They see their model of grassroots democracy as one that can be implemented throughout Syria in the future.

Social revolution

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

After declaring autonomy, grassroots organizers, politicians and other community members have radically changed the social and political make-up of the area. The extreme laws restricting independent political organizing, women's freedom, religious and cultural expression and the discriminatory policies carried out by the Assad government have been superseded. In their place, a Constitution of Rojava guaranteeing the cultural, religious and political freedom of all people has been established. The constitution also explicitly states the equal rights and freedom of women and also "mandates public institutions to work towards the elimination of gender discrimination".[21]

The political and social changes taking place in Rojava have in large part been inspired by the libertarian socialist politics of Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan.[21]

Cooperative economy

The Rojava economy is a blend of private companies, the autonomous administration and worker cooperatives. Since the revolution, efforts have been made to transition the economy to one of self-sufficiency based on worker and producer cooperatives. This transition faces the major obstacles of ongoing conflict and an embargo from all neighboring countries: Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and the various forces controlling nearby areas of Syria. This has forced people to rely almost exclusively on diesel-run generators for electricity. Additionally, strong emphasis is being placed on businesses that can bring about self-sufficiency to the region.

There were at first no direct or indirect taxes on people or businesses in the region;[48] Instead the administration funded itself mainly through the sale of oil and other natural resources and tariffs on border commerce (which is clandestine because of the embargo).[49][50] However, in July 2017, it was reported that the administration in the Jazira Region had started to collect income tax to provide for public services in the region.[51] There are partnerships that have been created between private companies and the administration. The administration also funds the school system and distributes bread to all citizens at a below-market rate.[52]

The Movement for a Democratic Society Economic Committee has been helping businesses move towards a "community economy" based on worker cooperatives and self-sufficiency.[52]

Other cooperatives involve bottled mineral water, construction, factories, fuel stations, generators, livestock, oil, pistachio and roasted seeds, and public markets.

Additionally there are several agricultural communes with families collectively working the land.[53]

According to the region's "Ministry of Economics", by 2015, approximately three-quarters of all property had been placed under community ownership and a third of production had been transferred to direct management by workers' councils.[54]

Direct democracy

The Rojava Cantons are governed through a combination of district and civil councils. District councils consist of 300 members as well as two elected co-presidents, one man and one woman. District councils decide and carry out administrative and economic duties such as garbage collection, land distribution and cooperative enterprises.[55] Civil councils exist to promote social and political rights in the community.

Ethnic minority rights

Closely related to religious freedom and the protection of religious minorities is the protection of ethnic minorities. Kurds now have the right to study their language freely, as do Assyrians. For the first time, a Kurdish curriculum has been introduced to the public school system.

Residents are also now free to express their culture freely. Culture and music centers have formed, hosting dance classes, music lessons and choir practice.[56]

In some areas, in addition to the gender quota for councils, there is also an ethnic minority quota.[57]

There has been, however, numerous instances of discrimination toward Assyrians, including policies of seizing the property of Assyrians who had to flee due to conflict, and numerous instances of attacks against the Assyrian minority.[58] Kurdish authorities have also shut down privately run Assyrian schools ostensibly to protect students from "exorbitant tuition costs".[59][60]

Restorative justice

Rojava's criminal justice system incorporates principles of restorative justice.[61][62] Reconciliation Committees have replaced the Syrian government court system in several cities.[63] Committees are representative of the ethnic diversity in their respective area. For example, the committee in Tal Abyad has Arabs, Kurds, Turkmen and Armenians.[64]

Women's rights

Women’s revolution in Rojava

Rojava is famous for its attempt at overcoming gender inequality and improving women's rights.[65] In the Rojava Revolution, women's participation has achieved a lot of media attention in recent years. A lot of Kurdish women bound their power, gathered their weapons, and served in the mobile company of the Women's Protection Units (YPJ) on the front line in Syria.[66] The revolution in Rojava is mainly caused by the underlying dominant ideology, namely a secular egalitarian ideology.[67] Influenced by the ideology of Abdullah Öcalan, women have taken up their arms and have been fighting for a liberated Kurdistan. Ideologies that include an active fight for gender equality lead to the equal inclusion of women in military positions.[67]

Within the Kurdish forces, and especially regarding its leadership positions, there is an unprecedentedly high prevalence of female fighters.[68] The YPJ is a unique case where women embody a substantial part of the overall military force. The traditional belief, that combat is a male-dominated area and women simply are victims of that fact, is thereby compromised.[68]

Underlying ideology: Jineology

A strong political ideology, namely the Democratic Autonomy concept of Abdullah Öcalan, has had a major impact on female empowerment.[65] Öcalan, political activist and founder of the PKK, has the belief that a society needs to make decisions with consent from all members.[69] A nation should be based on this kind of democracy, as well as ecology and women's freedom.[69] Öcalan brought the concept of democratic confederalism to life, which encouraged a move away from patriarchal nationalism.[70] Within this concept, feminism, specifically jineology (the science of women), is central to the social revolution taking place in Rojava. The Democratic Autonomy concept has been modified to the ongoing conflict in Syria.[65] All YPG and YPJ fighters and Asayish have the study of jineology as part of their training, and it is also taught in community centers.[71] In 2017, the University of Rojava established the department of Jineology integrated in Languages and Social Studies Faculty.[72] The aim was to "teach the reality of life and women and redefine them and achieve changes in the mentality of the society".[73]

Legal revolution

Aside from the military victories, Rojava is the witness of a legal revolution. Since the war broke out there have been multiple legal changes regarding women's rights.[74] In the Social Contract of the Autonomous Regions of Kobane, Jazira and Afrin, formulated in 2014, it is stated that women and men have the same rights.[75] Much of the focus of the revolution has been on addressing the extreme levels of violence which women in the area have endured,[76] as well as increasing women's leadership in all political institutions. To illustrate, the authority of Rojava has come up with an initiative to install a 40% quota representation of women in every organization and institution.[74][77] This has the consequence that in every layer of government, from a local organization to the parliament, women must be assigned as vice presidents or co-presidents.[74] Also, efforts are being made to reduce cases of underage marriage, polygamy and honor killings, both socially as well as through legislation forbidding these practices.[78]

Women’s Protection Unit (YPJ)

In the 1980s, political organizations began recruiting women for their political and military ranks. An example of such a political organization was the Kurdish Workers Party, the PKK.[70] The extent to which women participate in the PKK and the YPG demonstrates the outstanding roles they have had in the battle with ISIS.[79] The YPG can be seen as the National Liberation Movement and the women from the YPJ have been fighting side by side with them. Both forces, YPJ and YPG, are under the control and command of the Democratic Union Party (PYD).[74] Their combaters are trained both militarily and educationally, as they are introduced to the political thought of Öcalan and jineology.[80] The Rojava Model perceives women as revolutionary operators who fight for improving democratic values. Women not only stimulate emancipation in society but further tackle the system which allows men to have internalized hegemony over women.[65] Therefore, women are highly visible as female fighters in the YPJ against ISIS.

Women's houses

In every town and village under YPG control, a women's house is established. These are community centers run by women, providing services to survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault and other forms of harm. These services include counseling, family mediation, legal support, and coordinating safe houses for women and children.[77] Classes on economic independence and social empowerment programs are also held at women's houses.[81]

Religious freedom

The right to religious expression is also safeguarded in the constitution. This, as well as the extreme hostility towards religious minorities in Islamist controlled areas, has led to a large migration of religious minorities to Rojava.[82]

Relations and conflicts

There are four major forces involved in the Rojava revolution. The People's Protection Units are working with the PYD and other political parties to establish self-rule in Rojava. Syrian government forces still maintain rule in some areas of Rojava under the leadership of the Assad government. A collection of Sunni Islamist forces, the largest being the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), fought to rule the region by way of Islamic fundamentalism. Finally, there were several militias under the general banner of the Free Syrian Army whose intentions and alliances have differed and shifted over time.

Rojava–Syrian government relations and conflicts

While conflict between the YPG and the Syrian government has not been as active as fighting against Islamist forces, there have been several conflicts between the two forces. Territory once controlled by the Syrian government in both Qamishli and al-Hasakah has been taken over by YPG forces. At the end of April 2016, clashes erupted between government forces and YPG fighters for control of Qamishli.[83]

As of the beginning of August 2016, YPG fighters controlled two-thirds of the northeastern city of al-Hasakah, while pro-government militias controlled the remainder. On 17 August 2016, heavy clashes broke out between YPG fighters and the pro-government militias, resulting in the deaths of four civilians, four Kurdish fighters, and three government loyalists. On 18 August, Syrian government aircraft bombed YPG positions in Hasakah, including three YPG checkpoints and three YPG bases. Syrian Kurds had recently demanded that the pro-government National Defense Forces militia disband in al-Hasakah. A government source told the AFP that the air strikes were "a message to the Kurds that they should stop this sort of demand that constitutes an affront to national sovereignty".[84] Another possible factor behind the fighting may have been the recent thaw in Turkish–Russian relations that began in July 2016; Russia, a key ally of the Syrian government, had previously been supporting Syrian Kurdish forces as a means to apply pressure to Turkey. After the recent territorial defeat of ISIL in Syria and Iraq and improvements in the Turkish–Russian relationship, it is possible that Russia and its allies began to view a strong YPG as increasingly less useful.[85]

In response to the attacks by the Syrian aircraft on Kurdish positions near al-Hasakah, the United States scrambled planes over the city in order to deter further attacks.[85]

By 22 August, Syrian government troops, Hezbollah fighters, and members of the Iranian paramilitary Basij militia had become involved in the fighting against Kurdish forces in al-Hasakah.[85]

In October 2023, in response to a series drone strikes on U.S. bases in Syria and Iraq, the Kurdish forces fight Syrian militias. 3 Kurdish militiamen and 19 Syrian militiamen were killed while 20 Syrian militiamen were injured.[86]

Internal relations and conflicts in Rojava

On 28 December 2012, Syrian government forces opened fire on pro-FSA demonstrators in al-Hasakah city, killing and wounding several individuals. Arab tribes in the area attacked YPG positions in the city in reprisal, stating the Kurdish fighters were collaborating with the government. Clashes broke out, and three Arabs were killed, though it was not clear whether they were killed by YPG forces or nearby government troops.[87] Demonstrations were organised by various Kurdish groups throughout northeastern Syria in late December as well. PYD supporters drove vehicles at low speeds through a KNC demonstration in Qamishli, raising tensions between the two groups.[88]

From 2 to 4 January, PYD-led demonstrators staged protests in the al-Antariyah neighbourhood of Qamishli, demanding "freedom and democracy" for both Kurds and Syrians. Many activists camped out on site. On 4 January, approximately 10,000 people were participating in the rallies, which also included smaller numbers of supporters of other Kurdish parties,[89] such as the KNC, which staged a rally in the Munir Habib neighbourhood. PYD organisers had planned for 100,000 people to participate, but such support did not materialise. The demonstrations were concurrent with rallies conducted across the country by the Arab opposition, though Kurdish parties did not use the same slogans as the Arabs, and also did not the same slogans amongst their own parties. Kurds also demonstrated in several other towns, but not across the entire Kurdish region.[90]

Meanwhile, several armed incidents occurred between the dominant PYD-YPG and other Kurdish parties in the region, particularly the Kurdish Union ("Yekîtî") Party, part of a Kurdish political coalition called the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union formed on 15 December 2012, which excludes the PYD.[91] On 3 January, PYD gunmen staged a drive-by shooting on a Yekîtî office in Qamishli. Armed Yekîtî members returned fire, injuring one PYD member.[92] The same day, armed clashes broke out between YPG fighters and members of the newly formed Jiwan Qatna Battalion of Yekîtî in ad-Darbasiyah. Four Yekîtî members were abducted by the YPG, who said they were affiliated with Islamist groups, though Yekîtî activists stated that the PYD wanted to prevent other Kurdish groups from arming themselves. Following demonstrations in the town demanding their release and an intervention by the KNC, the four men were released by the end of the day.[93] On 11 January, YPG forces raided an empty Yekîtî training ground near Ali Faru which had been built in early January, tearing down both the Kurdish and FSA flags that had been flying at the base. Though PYD members defended the raid by saying that the flags could have attracted government airstrikes, Yekîtî condemned the action.[94]

On 31 January, Kamal Mustafa Hanan, editor-in-chief of Newroz (a Kurdish-language journal) and a former Yekîtî politician, was fatally shot in the Ashrafiyah district of Aleppo. It was not clear if he was the victim of a stray bullet or of a politically motivated assassination. Yekîtî organised a funeral procession in the town of Afrin in the Kurdish-held northwest corner of Aleppo Province on 1 February, which members of both the PYD and KNC attended.[95] Also on 1 February, Kurds staged demonstrations in several towns and villages across West Kurdistan concurrent with opposition demonstrations elsewhere in the country. The demonstrations were organised by various Kurdish groups, including the PYD and KNC. Demonstrators from the KNC demanded an end to fighting in Ras al-Ayn and the withdrawal of armed groups from the town, while PYD demonstrators stressed solidarity with their YPG units and the Kurdish Supreme Council.[96]

From 2 to 5 February, YPG forces blockaded the village of Kahf al-Assad (Kurdish: Banê Şikeftê), inhabited by members of the Kurdish Kherikan tribe, after being fired upon by unknown gunmen in the village. YPG checkpoints were also established around other Kherikan villages. The Kherikan are traditionally supporters of the Massoud Barzani government of Iraqi Kurdistan, and as oppose the PYD. The blockade was the third time in two years that hostilities had broken out between the PYD/YPG and locals from Kahf al-Assad.[97]

On 7 February, YPG members kidnapped three members of the opposition Azadî party in Ayn al-Arab.[98]

On 22 February, Osman Baydemir, mayor of the city of Diyarbakır in Turkey, announced the initiation of a one-month humanitarian aid programme in which his city—along with the surrounding districts of Bağlar, Yenişehir, Kayapınar, and Sur—would provide food assistance to Kurdish areas in Syria affected by the war, which had received little of the humanitarian aid that other regions of Syria had received.[99]

On 11 April 2016, PYD supporters attacked the offices of the Kurdish National Council and the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria in Derbessiye and Qamishli.[100] The head of the Kurdish National Council told Turkey's TRT World channel the "PYD's oppressive attitude in Syria is forcing Kurds to leave the region".[101]

On 16 January 2017, more than 270 Syrian Kurdish activists signed an appeal calling for unity talks between the main Syrian Kurdish parties. In response, the Movement for a Democratic Society led by the PYD stated that they welcome unity and called on the Kurdish National Council to participate in federal project. The KNC led by the KDP-S, in response, demanded the release its political prisoners detained in Rojava. The KNC has rejected the federalism project launched by the Syrian Democratic Council and stated that it will participate in the peace talks in Astana, Kazakhstan, with Turkey and Russia. The Kurdish National Alliance in Syria, part of the SDC also welcomed the proposal of unity.[102]

On 3 February 2017, amidst clashes between the KDP-S-affiliated Peshmerga group and the Sinjar Resistance Units in Sinjar, a KNC office was burned in Qamishli and another attacked in Dirbêsiyê. The KNC said the pro-PYD youth group the Ciwanen Soresger was perpetrating the attacks. However, the perpetrators were reportedly arrested by the Asayish.[103]

On 3 March 2017, the Rojava Asayish arrested more than 40 members of the KNC in Syria while the KDP Asayish arrested 23 opposition protesters in Iraqi Kurdistan. 17 of them were later released but 6 were still imprisoned. By 16 March, more than 13 KNC offices and an Assyrian Democratic Organization office in Rojava were shut down by Rojava Asayish forces, reportedly for failing to register with PYD authorities. In response, the Human Rights Watch called on both sides to "immediately" release all "arbitrarily held political detainees".[104] The Mesopotamia National Council announced their support for TEV-DEM's requirement for parties to apply to licenses to operate in Rojava. However, the council also called for the self-management to give sufficient time for applications and denounced "random" closing of the parties' offices.[105]

On 3 April 2017, the Kurdish National Council called on the PYD to release 4 of its detainees: a Kurdish Future Movement in Syria member, a Kurdish Youth Movement member, and two KDP-S members. As of the same day, 6 detainees were still held by Iraqi Kurdish authorities.[106]

On 12 April 2017, an official in TEV-DEM met with Gabriel Moushe Gawrieh, head of the Assyrian Democratic Organization, and discussed the closure of the latter's offices since March. It was the first time TEV-DEM officials met with the ADO.[107]

Syrian Kurdish–Islamist conflict

The Syrian Kurdish–Islamist conflict is a major theater in the Syrian Civil War, starting in 2013 after fighting erupted between the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) and Islamist rebel factions in the city of Ras al-Ayn. Kurdish forces launched a campaign in an attempt to take control of the Islamist-controlled areas in the governorate of al-Hasakah and some parts of Raqqa and Aleppo governorates after al-Qaeda in Syria used those areas to attack the YPG. The Kurdish groups and their allies' goal was also to capture Kurdish areas from the Arab Islamist rebels and strengthen the autonomy of the region of Rojava.[108]

YPG forces as well as later the broader Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) have clashed heavily with Islamist forces of all stripes in the following years, in particular with those representing the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Including the Siege of Kobanî (2014), the Al-Hasakah offensive (February–March 2015), the Al-Hasakah offensive (May 2015), the Tell Abyad offensive (May–July 2015), the Battle of Sarrin (June–July 2015), the Battle of Al-Hasakah (June–August 2015), and the Raqqa campaign (2016–2017) including the Battle of Tabqa (2017).

Rojava–Turkey conflict

Turkey has long called the PYD as a Syrian extension of the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), and has therefore taken a hardline stance against the group, the official talking point being that it would not allow a Kurdish state to form along their southern border with Syria. Turkey's policy towards Rojava is based on an economic blockade,[109] persistent attempts of international isolation,[110] opposition to the cooperation of the international Anti-ISIL-coalition with Rojava militias,[111] and support of Islamist Syrian Civil War parties hostile towards Rojava,[112][113] in past times even including ISIL.[114][115][116] Turkey has on several occasions been militarily attacking Rojava territory and defence forces.[117][118][119] The latter has resulted in some of the most clearcut instances of international solidarity with Rojava.[120][121][122]

Turkey received PYD co-chair Salih Muslim for talks in 2013[123] and in 2014,[124] even entertaining the idea of opening a Rojava representation office in Ankara "if it's suitable with Ankara's policies".[125] Turkey recognizes the PYD and the YPG militia as identical to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK),[126][127][128][129] which is listed as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the European Union, the United States and others. However, the EU, the US, and others cooperate with the PYD and the YPG militia in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and do not designate either a terrorist organisation.[130] About its loss in international standing, the consequence of domestic and foreign policies of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish government is contemptuous.[131][132][133] The Turkish foreign minister called the PYD a "terrorist organisation" in his speech at the meeting of Council of Foreign Ministers of the 13th Islamic Summit of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) on 12 April 2016 at Istanbul, Turkey.[110] In November 2016 a state-run media organization of Turkey, Anadolu Agency, stated that the educational institutions of Rojava had "prejudice against Islam".[134] U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter said there were links between the PYD, the YPG, and the PKK.[135][136][137] Secretary Carter replied, "Yes," to a Senate panel when Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) asked whether he believed the Syrian Kurds are "aligned or at least have substantial ties to the PKK".[138] Rojava and YPG leaders state that the PKK is a separate organization.[139] YPG representatives have persistently reiterated that their militia has an all Syrian agenda and no agenda of hostility whatsoever towards Turkey.[140] However, according to the Turkish Daily Sabah, at one occasion in January 2016 "a YouTube video has appeared of an English-speaking man, reported to be a fighter from the Democratic Union Party's (PYD) armed wing, the People's Protection Units (YPG) (...) making a call for Westerners to join the ranks of the armed group and conduct terrorist attacks against the Turkish state."[141] In the perception of much of the Turkish public, the Rojava federal project as well as U.S. support for the YPG against ISIL are elements of a wider conspiracy scheme by a "mastermind" with the aim to weaken or even dismember Turkey, in order to prevent its imminent rise as a global power.[142]

Following YPG successes in 2015, including the capture of Tell Abyad, Turkey began targeting YPG forces in northern Syria.[143] On 16 February 2016, Turkish forces began shelling Kurdish forces in the Afrin District after the SDF took initiative from an SAA offensive and captured rebel-held areas of the Azaz District, including Tell Rifaat and Menagh Airbase. Turkey vowed not to allow the SDF to capture the key border town of Azaz. As a result, 25 Kurdish militants were killed and 197 injured from Turkish artillery fire.[144] In early 2016, following the capture of Tishrin Dam, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) were allowed to cross the Euphrates River, a proclaimed 'red line' by Turkey. Turkish forces bombed the Kurdish YPG headquarters in Tell Abyad, destroying three armoured vehicles and injuring two Kurdish fighters.[145] The following day, 21 January 2016, Turkish troops crossed the border into Syria and entered the ISIL-controlled Syrian border town of Jarabulus which the YPG had been planning on capturing as part of an offensive to unite their areas of control into one continuous banner of territory. Kurdish-led forces in northern Syria said Turkish airstrikes hit their bases in Amarneh village near Jarablus on 27 August 2016, after Turkish artillery shelled the positions the day before.[146] The Syrian Observatory reported on 27 August 2016, about exchange of gunfire between YPG and the Turkish forces in the countryside north of Hasakah. It is unclear if Turkish forces were on Syrian territory or had fired across the border.[147]

In March 2017, U.S. Lieutenant General Stephen Townsend said "I have seen absolutely zero evidence that they have been a threat to, or have supported any attacks on, Turkey from Northern Syria over the last two years." The top U.S. commander in the campaign against Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) stated that the Peoples’ Protection Units (YPG), the military wing of the Syrian Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD), does not pose a threat to Turkey. "Of those YPG fighters, I’ve talked to their leaders and we’ve watched them operate and they continually reassure us that they have no desire to attack Turkey, that they are not a threat to Turkey, in fact that they desire to have a good working relationship with Turkey."[148]

See also

- Cities and towns during the Syrian Civil War

- Democratic confederalism

- International Freedom Battalion

- Syrian Democratic Forces

- Syrian Kurdish–Islamist conflict (2013–present)

- Kurdish–Turkish conflict (2015–present)

- Kurdish rebellion of 1983

- Kurdish women

- A Modern History of the Kurds by David McDowall

Notes

- ^ Since 12 September 2014[2]

- ^ a b Syrian Government has both clashed and cooperated with Rojava during various stages of the conflict

- ^ a b Russia has cooperated with Rojava during the Northern Aleppo offensive (February 2016) and Second Northern Syria Buffer Zone while clashing it during the Battle of Khasham

- ^ (ex-Free Syrian Army but still rebel allied brigade)

- ^

- 29 killed during Operation Peace Spring[14]

- 91 killed during Operation Olive Branch[15]

- 125 killed during Battle of al-Hasakah (2015)[16][17]

- ^ 3 in ES,[1] 6 in PS [2]

- ^ 8 in ES,[3] 3 in OB,[4] 3 in PS [5]

- ^ 5 in ES,[6] 5 in PS [7]

- ^

- ^ 43 in ES,[8] 21 in OB,[9] 49 in PS [10]

- ^ 33 in ES,[11] 23 in OB,[12] 9 in PS [13]

- ^ 4 in OB,[14] 12 in ES,[15] 14 in PS [16]

- ^

- ^

- 7 killed during Battle of Qamishli (2021)[17][18]

- 11 killed during Qamishli clashes (2018)[19]

- 68 killed during Battle of Khasham[20]

- 77 killed during Battle of al-Hasakah (2016)[21]

- 22 killed during Battle of Qamishli (2016)[19]

- 376 killed in 2013 [22]

References

- ^ "PYD Announces Surprise Interim Government in Syria's Kurdish Reg". Rudaw. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "YPG and FSA launch joint military operations against Islamic State in northern Syria". ARA News. 13 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ Anon. "Revolution in Rojava: Democratic Autonomy in Kurdistan". Center for a Stateless Society. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Colella, Chris (Winter 2017). "The Rojava Revolution: Oil, Water, and Liberation – Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation". Commodities, Conflict, and Cooperation. Evergreen State College. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Prichard, Alex; Kinna, Ruth; Pinta, Saku; Berry, David, eds. (2017). "Preface". Libertarian Socialism: Politics in Black and Red (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: PM Press. ISBN 978-1-62963-390-9.

- ^ a b "Rojava, Syria: A revolution of hope and healing". The Vancouver Observer. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Al-Qaeda suffered heavy losses against the Kurdish forces". 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "Internationalist Freedom Brigade Established in Rojava". Kurdish Question. 11 June 2015. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Moore, Harriet (11 June 2015). "OSINT Summary: Pro-Kurdish foreign fighters group established in Syria". Jane's Terrorism and Security Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ a b Haras, Nicholas A. (24 October 2013). "The Battle for Syria's Al-Hasakah Province". Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (13 December 2013). "Kurdish Strategy Towards Ethnically-Mixed Areas in the Syrian Conflict". Terrorism Monitor. 11 (23). Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Chris Tomson (23 October 2016). "Kurdish forces capture village in northern Aleppo as the Turkish Army redeploys". al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 3 February 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Syrian Revolution 13 years on | Nearly 618,000 persons killed since the onset of the revolution in March 2011". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Syrian Democratic Forces continue to comb the villages and sites to which the pro-Turkish factions advanced on the outskirts of Ain Issa" (in Arabic). Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 24 November 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "On the eve of Nowruz festivals…Afrin witnesses arrests against its residents by the factions of "Olive Branch" on charge of celebrating and setting fire in the festival's anniversary". 6 February 2024. Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 21 March 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Syria Army, Kurds Push Islamic State Out of Hasakeh City: Report". Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ jack. "13 regime forces killed and wounded in al-Hasakah city". Syrian Observatory For Human Rights. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ "In one month, International Coalition limits its control to oil fields, and Russia becomes a new player in northern and northeastern Syria". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Kurdish forces to keep areas taken from Syrian government forces truce". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Schmidinger, Thomas. Krieg und Revolution in Syrisch-Kurdistan: Analysen und Stimmen aus Rojava.

- ^ a b c d Enzinna, Wes (24 November 2015). "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ a b Gorgas, Jordi Tejel (2009). "Les territoires de marge de la Syrie mandataire : le mouvement autonomiste de la Haute Jazîra, paradoxes et ambiguïtés d'une intégration " nationale " inachevée (1936–1939)". Revue des Mondes Musulmans et de la Méditerranée (126). doi:10.4000/remmm.6481. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "The Silenced Kurds". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "Minority Kurds struggle for recognition in Syrian revolt". The Daily Star Lebanon. 31 March 2012. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Brandon, James (21 February 2007). "The PKK and Syria's Kurds". Terrorism Monitor. 5 (3). Washington, DC: The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ Isseroff, Ami (24 March 2004). "Kurdish agony – the forgotten massacre of Qamishlo". MideastWeb. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Stack, Megan K. (14 August 2005). "Cleric's Slaying a Rallying Cry for Kurds in Syria". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Iddon, Paul. "A recap of the Syrian crisis to date". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Jailed Kurds on Syria hunger strike: rights group". Agence France-Presse. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Khatib, Lina; Lust, Ellen (1 May 2014). Taking to the Streets: The Transformation of Arab Activism. JHU Press. p. 161 of 368. ISBN 978-1421413136. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Many arrested in Syria after protests". Al Jazeera. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ "Guide to the Syrian rebels". BBC News. 13 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ Furuhashi, Yoshie (29 May 2011). "Syrian Kurdish Parties Boycott Syrian Opposition Conference in Antalya, Turkey". Monthly Review. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Most Syrian Kurdish Parties Boycott Opposition Gathering". Rudaw. 29 August 2011. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds Try to Maintain Unity". Rudaw. 17 July 2012. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Syria: Massive protests in Qamishli, Homs". CNTV. 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish Official: Now Kurds are in Charge of their Fate". Rudaw. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ^ a b "More Kurdish Cities Liberated As Syrian Army Withdraws from Area". Rudaw. 20 July 2012. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "After quiet revolt, power struggle looms for Syria's Kurds". Mobile.reuters.com. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ "City of Derik taken by Kurds in Northeast Syria". Firat news. 21 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Ban: Syrian regime 'failed to protect civilians'". CNN. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Clashes between Kurds and Syrian army in the Kurdish city of Qamişlo, Western Kurdistan". Ekurd.net. 21 July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Abdulmajid, Adib (22 July 2012). "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Girke Lege Becomes Sixth Kurdish City Liberated in Syria". Rudaw. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Davies, Wyre (27 July 2012). "Crisis in Syria emboldens country's Kurds". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "PYD Press Release: A call for support and protection of the peaceful establishment, the self-governed Rojava region | هيئة التنسيق الوطنية لقوى التغيير الديمقراطي". Syrianncb.org. 24 February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Syria – News". Peter Clifford Online. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "The Economy of Rojava". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Poor in means but rich in spirit". Ecology or Catastrophe. Archived from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Efrîn Economy Minister Yousef: Rojava challenging norms of class, gender and power". Diclenews.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Wladimir van Wilgenburg (11 July 2017). "Rojava Administration to Impose Tax System in Northern Syria". Co-operation in Mesopotamia. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Rojava's Threefold Economy". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "The Experience of Co-operative Societies in Rojava". Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ A Small Key Can Open a Large Door: The Rojava Revolution (1st ed.). Strangers in a Tangled Wilderness. 4 March 2015.

According to Dr. Ahmad Yousef, an economic co-minister, three-quarters of traditional private property is being used as commons and one quarter is still being owned by use of individuals...According to the Ministry of Economics, worker councils have only been set up for about one third of the enterprises in Rojava so far.

- ^ Tax, Meredith. "The Revolution in Rojava". Dissent Magazin. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "A Kurdish Spring in Syria". DW. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Rojava: only chance for a just peace in the Middle East". March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "Assyrians Under Kurdish Rule: The Situation in Northeastern Syria" (PDF). January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Closure of Syrian Schools: Another Bleak Sign for Christians in Syria". National Review. 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ "Why are Kurdish authorities shutting down dozens of private schools in northeast Syria?". 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Laursen, Eric (4 May 2021). The Operating System: An Anarchist Theory of the Modern State. AK Press. ISBN 9781849353885. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ Quirico, Monica; Ragona, Gianfranco (5 July 2021). Frontier Socialism: Self-Organisation and Anti-Capitalism. Springer. ISBN 9783030523718. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Reconciliation Committee Solves 1977 cases in Serekaniye". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Reconciliation Committee replaces courts in Girê Spî". Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d Burç, Rosa (2020). "Non-territorial autonomy and gender equality: The case of the autonomous administration of north and east Syria - Rojava". Filozofija I Drustvo. 31 (3): 319–339. doi:10.2298/FID2003319B. ISSN 0353-5738. S2CID 226412887. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "The Rojava revolution". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b Haner, Murat; Cullen, Francis T.; Benson, Michael L. (September 2020). "Women and the PKK: Ideology, Gender, and Terrorism". International Criminal Justice Review. 30 (3): 279–301. doi:10.1177/1057567719826632. ISSN 1057-5677. S2CID 150900998. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b Wood, Reed M; Thomas, Jakana L (January 2017). "Women on the frontline: Rebel group ideology and women's participation in violent rebellion". Journal of Peace Research. 54 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1177/0022343316675025. ISSN 0022-3433. S2CID 152263427.

- ^ a b Öcalan, Abdullah (2017). The Political Thought of Abdullah Öcalan: Kurdistan, Woman's Revolution and Democratic Confederalism. Pluto Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1n7qkks. ISBN 978-0-7453-9977-5. JSTOR j.ctt1n7qkks. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ a b Düzgün, Meral (1 July 2016). "Jineology". Journal of Middle East Women's Studies. 12 (2): 284–287. doi:10.1215/15525864-3507749. ISSN 1552-5864. S2CID 151783142. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Argentieri, Benedetta (30 July 2015). "These female Kurdish soldiers wear their femininity with pride". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Jineology: Knowledge, experience, and science of women-2". JINHAGENCY News. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ "Department of Jineology(Women's Science ) |". Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Rojava revolution". openDemocracy. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Political System: Documents – Rojava Information Center". rojavainformationcenter.com. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Üstündağ, Nazan (2016). "Self-Defense as a Revolutionary Practice in Rojava, or How to Unmake the State". South Atlantic Quarterly. 115 (1): 197–210. doi:10.1215/00382876-3425024. ISSN 0038-2876. S2CID 147434474.

- ^ a b Owen, Margaret (11 February 2014). "Gender and justice in an emerging nation: My impressions of Rojava, Syrian Kurdistan". Ceasefire Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds give women equal rights, snubbing jihadists". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Meet the Women Taking the Battle to ISIS". Time. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ Öğür, Berkan; Baykal, Zana (7 July 2017), "Understanding "Foreign Policy" of the PYD/YPG as a Non-State Actor in Syria and Beyond", Non-State Armed Actors in the Middle East, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 43–75, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55287-3_3, ISBN 978-3-319-55286-6, retrieved 17 April 2023

- ^ "Revolution in Rojava transformed the perception of women in the society". Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ "Joint statement to the academic delegation at Rojava". 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ "Fighting Escalates in Syria's Qamishli". 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "MIDEAST - Syrian regime forces bomb Kurds in north for first time". 18 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Hawramy, Fazel (22 August 2016). "Kurdish militias fight against Syrian forces in north-east city of Hasaka". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "26 killed in clash between SDF, pro-Syrian regime armed group". Rudaw. 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Al-Hasakah: Deadly clashes between Arab tribes and PYD". KurdWatch. 9 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: PYD provokes supporters of the Kurdish National Council". KurdWatch. 4 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: Youth groups organize three-day rally". KurdWatch. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: PYD fails in attempt to mobilize one hundred thousand demonstrators". KurdWatch. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: Kurdish Democratic Political Union—Syria established". KurdWatch. 7 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: Shots exchanged between PYD and Yekîtî". KurdWatch. 12 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Ad-Darbasiyah: YPG abducts armed Yekîtî members". KurdWatch. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: YPG storms Yekîtî military drill ground". KurdWatch. 20 January 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ "Aleppo: Kurdish politician and writer fatally shot". KurdWatch. 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Qamishli: More demonstrations in the Kurdish regions". Kurd Watch. 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ "Al-Malikiyah: YPG ends siege of Kahf al‑Assad". KurdWatch. 11 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ^ "ʿAyn al-ʿArab: YPG abducts Azadî members". KurdWatch. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Diyarbakır mayors for Kurds in Syria". Firat News. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "PYD increases attacks on other Kurdish groups in Syria". Daily Sabah. 12 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ "Kurds fleeing Syria due to 'totalitarian' PYD's terror acts, oppressive attitude". Daily Sabah. 28 November 2016. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Despite calls for unity, Syrian Kurds remain divided". ARA News. 19 January 2017. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "After Kurdish tensions in Sinjar, KNC offices in Rojava under attack". ARA News. 5 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch calls on Syrian Kurds and KRG to release political prisoners". ARA News. 19 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF BETH NAHRIN ISSUED A STATEMENT REGARDING THE CLOSURE OF UNLICENSED PARTY OFFICES". Syriac International News Agency. 17 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Kurdish National Council calls on PYD to release political prisoners". ARA News. 4 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Wladimir van Wilgenburg (13 April 2017). "Assyrian faction linked to Syrian opposition meets with Kurdish TEV-DEM after office closure". ARA News. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "Syrie: les Kurdes combattent les jihadistes pour imposer leur autonomie - Dernières Infos - L'Orient-Le Jour". L'Orient-Le Jour. 19 July 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Meredith Tax (14 October 2016). "The Rojava Model". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ a b "From Rep. of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs". Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Turkish President Erdoğan slams US over YPG support". Hurryiet Daily News. 28 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "How Can Turkey Overcome Its Foreign Policy Mess?". Lobolog (Graham E. Fuller). 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ Wladimir van Wilgenburg (12 June 2015). "The Rise of Jaysh al-Fateh in Northern Syria". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ David L. Phillips (11 September 2014). "Research Paper: ISIS-Turkey Links". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Senior Western official: Links between Turkey and ISIS are now 'undeniable'". Businessinsider. 28 July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ Burak Bekdil (Summer 2015). "Turkey's Double Game with ISIS". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Turkey accused of shelling Kurdish-held village in Syria". The Guardian. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Turkey strikes Kurdish city of Afrin northern Syria, civilian casualties reported". Ara News. 19 February 2016. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Christopher Phillips (22 September 2016). "Turkey's Syria Intervention: A Sign of Weakness Not Strength". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ Fehim Taştekin (9 September 2016). "US backing ensures Arab-Kurd alliance in Syria will survive". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ "Germany warns Turkey from attacking Kurds in Syria". Iraqi News. 28 August 2016. Archived from the original on 14 May 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ U.S. Senator John McCain, Chairman of the United States Senate Armed Services Committee (27 October 2016). "Statement by SASC Chairman John McCain on Turkish Government Attacks on Syrian Kurds". Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- ^ "PYD leader arrives in Turkey for two-day talks: Report". Hurriyet Daily News. 25 July 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish leader holds secret talks in Turkey: reports". Yahoo. 5 October 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Salih Muslim's trip to Turkey and Incirlik Base". Yeni Safak. 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016.

- ^ "The YPG-PKK Connection". Atlantic Council. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Turkey v Syria's Kurds v Islamic State". BBC News. 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Daesh, FETÖ, YPG, PKK, Shabab terrorist groups are all the same". Yeni Şefak. 2 November 2016. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "British volunteers in Syrian Kurd forces are 'terrorists', Turkey says". Middle East Eye. 1 September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ "U.S. says YPG not a terrorist organization". ARA News. 23 September 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ "Turkey's domestic policy losing its foreign friends". Al Monitor. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Erdogan muddies Syrian and Iraqi political waters". Financial Times. 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 18 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı; Dr. Çağlar Kurç (10 October 2016). "Only Problems. How Turkey Can Become an Honest Mediator in the Middle East, Again". Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "PKK/PYD indoctrinating schoolchildren in N.Syria". Anadolu Agency. 21 November 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "US defense chief admits links among PYD, YPG, PKK - AMERICAS". 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Pentagon chief Carter confirms link between YPG/PYD and PKK terrorist organization". Daily Sabah. 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "US defense chief admits PYD, YPG, PKK link". Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "Stenographic Transcript Before the COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE HEARING TO RECEIVE TESTIMONY ON COUNTER-ISIL (ISLAMIC STATE OF IRAQ AND THE LEVANT) OPERATIONS AND MIDDLE EAST STRATEGY" (PDF). p. 99. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ Ivan Watson and Gul Tuysuz (29 October 2014). "Meet America's newest allies: Syria's Kurdish minority". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "A look at battle for Raqqa from a Kurdish perspective". Al Monitor. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "PYD/YPG terrorists call on Westerners to join group, attack Turkey". Daily Sabah. 28 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ "The Tin-Foil Hats Are Out in Turkey. From Zionist plots to CIA conspiracies, Turkey's favorite pastime is believing that the world is out to get it". Foreign Policy. 12 September 2016. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "Balance of the War Against Hostile Groups in Rojava, Northern Syria: Year 2015 – People's Defense Units Official Website". Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ "Turkish Air Strikes in Syria Kill 25 Kurdish Militants, Says Military". 28 August 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016 – via The New York Times.

- ^ "Turkey bombs Kurdish headquarters northern Syria - ARA News". ARA News. 20 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Kurdish-led Syria forces face off with Turkish-backed rebels". Associated Press. AP. 27 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "YPG and Turkey clash in northern Syria". Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ "YPG no threat to Turkey, US top general argues". Hurriyet Daily News. 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- 21st-century revolutions

- Conflicts in 2015

- Conflicts in 2016

- Kurdistan independence movement

- Kurdish rebellions in Syria

- Politics of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

- 2012 in the Syrian civil war

- 2013 in the Syrian civil war

- 2014 in the Syrian civil war

- 2015 in the Syrian civil war

- Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria

- Feminist movements and ideologies

- Islam-related controversies

- Military operations of the Syrian civil war

- Kurdish secession in Syria

- Socialism in Syria

- Socialist feminism

- Al-Hasakah Governorate in the Syrian civil war

- Raqqa Governorate

- Aleppo Governorate

- Military operations of the Syrian civil war involving the Syrian government

- Military operations of the Syrian civil war involving the Free Syrian Army

- Syrian civil war

- Socialist revolutions