Robert Poole (industrialist)

Robert Poole | |

|---|---|

Poole (seated), his son George, and grandson Robert, c. 1898 | |

| Born | 1818 |

| Died | 1903 (aged 84–85) United States |

| Occupation(s) | Engineer, inventor |

| Spouse |

Ann Simpson

(m. 1841; died 1891) |

| Children | 8 |

Robert Poole (1818-1903) was an Irish-born engineer, inventor, entrepreneur, and benefactor. In 1843 he founded an ironworks in Baltimore, Maryland. For his workforce he hired members of what would become the first generation of modern metalworkers (machinists, molders, patternmakers, and boilermakers)—an emerging trade whose numbers would swell to 250,000 nationally by the end of the 19th century.[1] His enterprise became the largest of its kind in Maryland,[2] with 800–850 employees, and, from the 1850s on, played a central role in the manufacture of iron-based infrastructure essential for private enterprise and public works in America.[3]

Poole’s company made the columns that encircle the base of the dome of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C., engines that powered Union gunships during the Civil War, hydraulic pumps that dredged the Potomac River (creating park land for national monuments), and complex devices (known as carriages) that controlled the raising and lowering of long-range guns for the defense of the U.S. coastline for the federal government.

For industry, the Poole company produced metal-based turbines and millwork that powered new and expanding manufacturers of flour, fertilizer, paper, and textiles—industries central to a growing economy. Municipalities bought Poole-made steam fire engines, horsecars that ran on rails, and mechanisms that drove urban cable cars—new services for the nation's burgeoning cities.

At Poole's death in 1903, a newspaper headlined his obituary "Captain of Industry Dead."[4] Poole did business in an era of wide-spread industrial strikes; his company went fifty years without one. At his funeral service, a delegation of two hundred and fifty men from his ironworks filed past his casket. Poole is recognized as a benefactor[5] for schools, colleges, and, most notably, a library which he had built and gave to the Enoch Pratt Free Library, the library system for the City of Baltimore.

Early life

[edit]As an only child Poole lived in a one-story dwelling on an eight-acre farm outside the village of Gulladuff, 40 miles (64 km) northwest of Belfast, in what would become Northern Ireland.[5] His father, George Poole (c. 1785-c. 1822), was a farmer; his mother, Mary Shields Poole (1783–1857) was a flax spinner. After his father's death, Poole, age 6, and his mother, 41, immigrated to Baltimore in 1824. (At the time, Baltimore was America's third largest and fastest growing city.) "She must have had friends there," his granddaughter wrote.[6] Poole’s mother supported the family as a seamstress and tutor, and she homeschooled her son.

Starting at the age of 15 Poole apprenticed with a blacksmith, with machinists in textile mills, and with the engineer Ross Winans in the shops of the fledgling Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. From these experiences, Poole learned about iron, metalwork, engines, machinery, and the organization of an industrial enterprise.[7]

Poole Ironworks

[edit]

In 1843, on the northern edge of Baltimore, Poole and his first partner, William Fergusson (1816–1863), hired a small crew of metalworkers and opened for business as the Baltimore Ironworks (generally known as Poole & Fergusson).[8]

During the 1840s and 1850s a tectonic shift had begun in the use of natural resources—away from wood (and its derivative, charcoal), long the nation's primary source of heat, and toward coal, soon to become the dominant fuel for heating homes and factories, for driving steam engines, and for smelting iron.[9] By using coal instead of charcoal (as a source of heat and carbon), together with a process known as hot blast (blowing hot air into smelting furnaces), operators could build larger, more efficient furnaces and vastly increase their production of pig iron (the raw material for finished iron-based products). What had been scarce and expensive became plentiful and affordable—helping set off a wave of industrial diversification that laid the foundation for the Poole company's expansion.

In 1851, because of disagreements over money and management, Poole ended his partnership with William Fergusson and took on, as his new partner, German H. Hunt (1828–1907), in a business they named the Union Works (generally known as Poole & Hunt). During their collaboration—until 1888, when Hunt retired—Poole managed internal operations of the ironworks; Hunt directed sales, bidding on contracts, and relations with the public.[10]

In 1853, after a fire in their foundry and machine shop, and a city-wide strike of metalworkers, the partners moved their operations from Baltimore to what was then the village of Woodberry,[11] a few miles north of the city. On farmland beside the Jones Falls (falls is a local word for river), they constructed a plant fifty percent larger than the in-town ironworks. Each craft had its own shop of one story; ample space between shops made possible the subsequent enlargement of the business.[12]

It was during this period of transition—to a new partnership and a new location—that Poole's company came to national attention with its work on the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. in the 1850s. Responsible for enlarging and modernizing the overcrowded building, the architect of the project, Thomas U. Walter made architectural history when he selected iron instead of marble for the thirty-six columns (known as a peristyle) that surround the base of the dramatic new dome he designed.

Forty miles away, Poole set precedent, too, when he cast the columns in deep pits in his new foundry. Molding iron in that way and for this purpose had not been accomplished before. The Poole company would go on to supply a total of 2.8 million pounds of structural iron for the new Capitol, chiefly for the dome.[13] For the Capitol project, Poole and Hunt took their instructions from Montgomery C. Meigs of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, superintendent of Capitol construction during the 1850s. (Meigs was later appointed by President Lincoln as Quartermaster of the Union Army during the Civil war).[14]

Simultaneous with the Capitol Project, Meigs was responsible for the building of the Washington Aqueduct, and contracted with the Poole company to supply a derrick, a steam engine, and a stone-smoothing machine for that project.[15] The Poole company worked again in Washington, D.C., in the 1880s, when its hydraulic pumps on barges sucked up muck and debris from the bottom of the Potomac River and, via a pipeline, deposited the material thousands of feet away, on the edge of the city, where it formed the ground for East Potomac Park, home to the Lincoln Memorial and other monuments.[16]

Over his lifetime, Poole was granted eleven patents—one for improving the durability of wheels on railroad rolling stock and another for a device that accelerated the heating of water before it entered a boiler.[17] His most successful invention was a revolving pan that mixed ingredients for commercial fertilizer, a mechanism that was widely adopted in the emerging fertilizer industry during the 1870s and 1880s.[18]

Poole’s openness to the innovations of others freshened his company’s array of products and added to its profitability. George Babcock and Stephen Wilcox, Jr. of Providence licensed the Poole company to manufacture their patented safety boiler. Its water was dispersed in many small tubes that resisted exploding under pressure, a significant improvement over conventional, so-called shell boilers, whose water was concentrated in a single container which, when overheated, could exploded easily and with fatal consequences.[19]

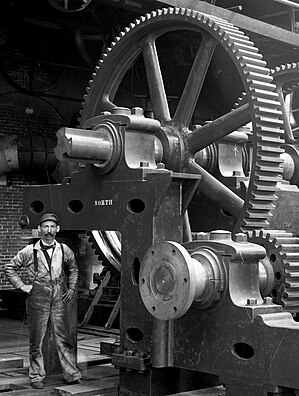

Robert Poole and Englishman John Walker collaborated on the manufacture and use of semi-automated, gear-molding machinery (an advance over cast and machine-cut gears) that, reportedly, sped production and improved their quality.[20] By the end of the nineteenth century, the Poole company was ranked as the leading maker of diversified industrial gearing in the United States—with gears that fit into a child's hand and stood as high as an elephant.[21]

Poole's most important alliance was with James Leffel of Springfield, Ohio, inventor of the so-called double turbine water wheel, a highly efficient mechanism that converted the energy of moving water into rotary power that drove machinery.[22] Leffel’s turbine, and turbines that Poole engineers designed on their own, enable the company to become a significant competitor in the generation and distribution of industrial power, particularly in textile mills in the South after the Civil War and in the paper-making industry in the Northeast.[23] The company’s largest single order—for forty custom-made turbines—was for the hydroelectric station at York Haven, Pennsylvania, beside the Susquehanna River. Twenty of these turbines continue to turn electricity-producing generators today.[24]

“Robert Poole was an exceptional engineer with remarkable insight into the future and anticipation of big things in engineering," wrote editor and author E.A. Suverkrop, in the American Machinist. (vol.52, no.3, 15 January 1920)

Benefactor

[edit]Poole responded to needs, one by one, as they came to his attention, not as part of any organized program of philanthropy. On land adjoining his ironworks, in the early 1880s, he underwrote the construction of a public school building that could house 350 pupils.[25] In the 1890s, he gave money to support both The Woman’s College (later Goucher College) and Morgan College (later Morgan State University), where he was a trustee (1893–1901).[26] Although he was a Methodist, Poole paid for rebuilding and enlarging St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Hampden-Woodberry.[27] In 1899, he financed the construction of a branch library in Hampden-Woodberry and donated the building and its books to the Enoch Pratt Free Library of Baltimore.[28] During his lifetime, his gifts to institutions totaled the modern equivalent of $4–5 million dollars. After his death in 1903, trustees learned that he held mortgages, many for long-time employees, worth $3.4 million today, only a fraction of which was repaid.[29]

Personal life

[edit]On 7 November 1841 Robert Poole and Ann Simpson (1818–1891) were married in the Emory Methodist Episcopal Church in her home town of Ellicott Mills, Maryland.[30] Ann Simpson was born in Washington, D.C., the youngest of five children of Welsh-born parents. She bore eight children, six of whom lived to adulthood.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ David R. Meyer, Networked Machinists: High Technology Industries in Antebellum America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2006), 17. Maier, Pauline, Merritt Roe Smith, Alexander Keyssar, and Daniel J. Kevles. “Changing Occupational Structure 1870– 1900,” Table 18.1, Inventing America: A History of the United States. (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2006), 517.

- ^ John Thomas Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County from the Earliest Period to the Present Day (Philadelphia: L.H. Everts, 1881), 838. “By 1881, Poole & Hunt was described as the largest iron works in Maryland…” From “Poole & Hunt Company Buildings”, Maryland National Register of Historic Places, 1973, National Register Reference Number, 73002194, Sec.7, p.1. (This report originally carried the reference number, B-1007.) https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/NR_PDFs/NR-184.pdf.

- ^ Steven C. Swett, The Metalworkers (Baltimore: The Baltimore Museum of Industry, 2022), 84–115 (U.S. Capitol), 116–121 (Washington Aqueduct), 123–130 (steam fire engines), 131–138 (horse cars), 139–144 (Union gunboats), 255–296 (fertilizer, textiles, inclined plane, lighthouses, dredging the Potomac River, pulp and paper mills, flour mills and grain elevators, urban cable cars), 307–330 (gun and mortar carriages, copper mining, hydroelectricity).

- ^ Baltimore American, 14, 16 and 18 January 1903 and The Sun, 15, 16 and 18 January 1903.

- ^ a b "Character sketches of Robert Poole emphasize that his charitable nature more than balanced his technological skill and bold business acumen." "Poole & Hunt Company Buildings", Maryland National Register, No. 73002194, Sec.8, p 2.

- ^ Anna Howard Poole, "Robert Poole & Family," Anna (Norwich, Vermont: Bragg Hill Press, 2000), 121.

- ^ Swett, The Metalworkers, 6–14.

- ^ Swett, The Metalworkers, 22–30.

- ^ Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. "Anthracite Coal and the Beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the United States," The Business History Review vol. 46, no. 2 (Summer 1972): 141–181; W. Ross Yates, "Discovery of the Process for Making Anthracite Iron," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography vol. 98, no. 2 (April 1974): 206–223; Vera F. Eliasberg, "Some Aspects of Development in the Coal Mining Industry, 1839–1918," in Output, Employment and Productivity in the United States after 1800: Studies in Income and Wealth, Dorothy S. Buck, ed. (New York: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1966), 405–439.

- ^ Swett, The Metalworkers, 27–30, 298–299.

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/df49ff2d-5cc7-416a-8b51-0f0228943942

- ^ "Poole & Hunt Foundry/Clipper Mill Park | Baltimore Industry Tours". www.baltimoreindustrytours.com.

- ^ William Allen, The Dome of the United States Capitol: An Architectural History (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1992), 31–32; Susan Brizzolara Wojcik, Thomas U. Walter and Iron in the United States Capitol: An Alliance of Architecture, Engineering and Industry [PhD diss., University of Delaware, 1998], 2/3:584–587. Swett, The Metalworkers, 114.

- ^ William C. Allen, "M. C. Meigs, Engineer-in-Charge", History of the United States Capitol (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2001), 215–262. Swett, The Metalworkers, 97–114.

- ^ Harry C. Ways, "Montgomery C. Meigs and the Washington Aqueduct," Montgomery C. Meigs and the Building of the Nation's Capital, ed. William C. Dickinson et al, (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2001), 21–48; https://www.nps.gov/places/washington-aqueduct.htm. Swett, The Metalworkers, 116–121.

- ^ Peter C. Hains, "Reclamation of the Potomac Flats at Washington, D.C.," address given on 20 December 1893, and printed in Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers vol. 31 (January–June 1894): 55–80. Gordon S. Chappell, East and West Potomac Park: A History (Denver, Colorado: National Park Service, June 1973), 67. Swett, The Metalworkers, 269–274.

- ^ U.S. patents “Improvement in Casting Car-Wheels” (1858, no. 20,022), “Improvement in feed water heaters (1865, no. 47,499). Swett, The Metalworkers, 194–199.

- ^ U.S. patent for “Improved Machine for Rubbing and Mixing” (1867, no. 65,268).

- ^ U.S patent for "Improvement in Steam Generators," issued to George H. Babcock and Stephen Wilcox, Jr., United States Patent no. 65,042, 28 May 1867. https://www.babcock.com/home/about/corporate/history. Swett, The Metalworkers, 214–220.

- ^ S. Grove, address to the Foundrymen's Association, 3 April 1895, in Philadelphia, reprinted in The Iron Age [11 April 1895]: 760.

- ^ Swett, The Metalworkers, 225–229.

- ^ Carl M. Becker, "James Leffel: Double Turbine Water Wheel Inventor,” Ohio History: The Scholarly Journal of the Ohio Historical Society 75, no. 4 (Autumn 1966): 200–211 (now The Ohio History Journal). Swett, The Metalworkers, 147–153.

- ^ For data on orders from Poole & Hunt’s customers for turbines, penstocks, and related machinery that the company filled between 29 June 1866 and 28 February 1901, see typed, three-page summary from Poole Collection, Division of Work & Industry, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Swett, The Metalworkers: textiles (259–262), C&O incline plane (263–267), pulp and paper(275–281), and flour (282–286).

- ^ A.J. Althouse, untitled manuscript on the early history of the York Haven hydroelectric power plant, dated May 1942, nine pages of typewritten text, plus photographs, in the possession of the York County Heritage Trust Library/Archives. “York Haven, Pa., Transmission Plant" in Electrical World and Engineer vol. 42, no. 12 (19 September 1903): 471–472; "Electrical Transmission System of the York Haven Water and Power Company," in Electrical World vol. 49, no. 9 (2 March 1907): 425–431. Major historical developments in the design of water wheels and Francis hydroturbines by B. J. Lewis, J. M. Cimbala, and A. M. Wouden at opscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/22/1/012020/pdf. Swett, The Metalworkers, 322–330.

- ^ Robert Poole Lease to the School Commissioners of Baltimore County, signed by Robert Poole; German H. Hunt; John L. Turner, President; and W. Horace Soper, secretary, on 19 September 1862, and recorded on 3 February 1863 (Baltimore County Circuit Court Land Records Liber GHC 36, folio 326–328). Deirdre Lane Durbin, "Hampden-Woodberry: A ‘Model’ of the Model Company Town,” in Hampden-Woodberry: Mill Communities of the Jones Falls Valley (University of Maryland, Spring 1988), Collection of the Enoch Pratt Free Library.

- ^ Edward N. Wilson, The History of Morgan State College: A Century of Purpose in Action (New York: Vantage Press, 1975), 177. The Sun, 21 January 1902.

- ^ The Sun, 19 November 1900, 18 March 1901. Poole gave seven acres to St. Mary’s Episcopal Church to enlarge its cemetery (The Sun, 21 February 1900).

- ^ “Woodberry Library. Mr. Robert Poole Gives The Site and Buildings. Seventh Pratt Branch" (The Sun, 2 August 1899). Swett, The Metalworkers, 341–348.

- ^ Swett, The Metalworkers, n13, 453. Data about Poole's private philanthropy comes from a study of his real estate transactions in Baltimore City and Baltimore County between 1851 and 1901, prepared in 2013 by Victoria Kinnear of Baltimore, researcher and genealogist, based on her examination of city and county deeds during these fifty years.

- ^ The Sun, 9 November 1841.

- ^ Poole family genealogy, Swett, The Metalworkers, 383.

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (May 2023) |