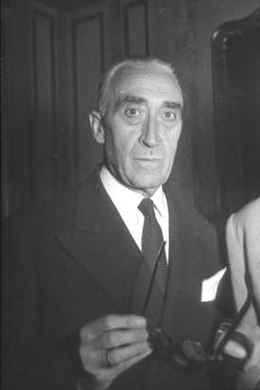

Ricardo Oreja Elósegui

Ricardo Oreja Elósegui | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ricardo Oreja Elósegui 1890 Ibarrangelu, Spain |

| Died | 1974 Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation(s) | lawyer, civil servant |

| Known for | politician, official |

| Political party | Carlism, PCP, PSP, UP, UMN, FET |

Ricardo Oreja Elósegui (1890-1974) was a Spanish Traditionalist politician. Initially in the Carlist ranks, he then joined the breakaway Mellistas, briefly engaged in Partido Social Popular, joined the primoderiverista state party Unión Patriótica, returned to Carlism within Comunión Tradicionalista and eventually settled in Francoist structures. He served in the Cortes during two terms between 1920 and 1923, and then during 5 terms between 1952 and 1965. In 1924-1927 he was the civil governor of the Santander province. In 1938 he formed part of the Gipuzkoan Comisión Gestora. In 1948-1954 he served one term in the Madrid city council, during some time as teniente de alcalde. In 1951-1965 he was sub-secretary in the Ministry of Justice. In 1934-1955 he presided over a large Gipuzkoan metalworking company, Unión Cerrajera.

Family and youth

[edit]

According to one source the Oreja family originated from Orexa, a mountainous hamlet in the province of Gipuzkoa;[1] according to another they were related to Arribe-Atallu, a neighboring small municipality in Navarre.[2] None of the sources consulted provides information on Ricardo's distant ancestors. His paternal grandfather Martin Oreja Arzadun[3] served as a rural physician; in the mid-19th century he was recorded in the Gipuzkoan branch of Sociedad Mutua General de Socorros Mutuos[4] but was noted also as related to Amoroto (Biscay) and Lanciego (Álava).[5] His son and the father of Ricardo, Basilio Oreja Echániz (1851-1914),[6] was also a doctor; at least since the late 1870s he settled in the Biscay town of Ibarrangelu[7] and in the early 20th century he served as its mayor.[8] At unspecified time but prior to 1878 he married Cecilia Elósegui Ayala (born 1853),[9] a girl from Villafranca de Ordizia and descendant to a much branched Gipuzkoan family.[10] The couple had 6 children, born between 1878 and 1891, but 2 siblings perished in early infancy.[11] Ricardo was born as the second youngest child.

It is not clear where the young Ricardo received his school education. In 1908 latest he enrolled in law at the University of Valladolid,[12] but in 1910 he was noted as resident in Madrid.[13] He was an excellent student and in 1912 he obtained Premio Montalbán.[14] He graduated at Universidad Central[15] in 1912.[16] The same year he was admitted to the civil service entrance examination leading to the title of Abogado del Estado,[17] but there was no follow up during the next few years. In 1916 he again entered the examination process,[18] passed to successive stages[19] and was eventually nominated the state lawyer; he ranked 18th on the list, topped by José Calvo Sotelo.[20] He assumed an unspecified law position in Madrid, and in 1919 moved to another unspecified legal job,[21] possibly in Direccion General de Prisiones.[22] In 1920 he was admitted to Colegio de Abogados of San Sebastián and in 1921 he was admitted to Colegio de Abogados of Madrid.[23]

In 1919 Oreja married María del Carmen Aspiunza García[24] (died 1938),[25] descendant to a Madrid bourgeoisie family originated from Amurrio. The couple settled in the capital.[26] They had one child,[27] Fernando Oreja Aspiunza (born 1925);[28] he made his name as a surgeon,[29] holding high positions in orthopedic association SECOT.[30] None of 4 grandchildren from the Oreja Igartúa family became a public figure;[31] most landed jobs in business.[32] Oreja's older brother Benigno Oreja Elósegui emerged as the Spanish urology pioneer and served many years in the Francoist Cortes. The younger brother Marcelino Oreja Elósegui was active as a businessman; killed by revolted workers he became one of the best-known victims of the 1934 revolution. His son and Ricardo's nephew, Marcelino Oreja Aguirre, was foreign minister in the late 1970s, secretary of Council of Europe in the 1980s and EU commissioner in the 1990s. Ricardo's grand-nephews, Marcelino Oreja Arburúa and Jaime Mayor Oreja, are also recognized PP politicians.

Late Restoration

[edit]

Political preferences of Oreja's ancestors are not clear, though all 3 brothers engaged in Carlism. Already during his academic years in Valladolid and in Madrid the young Ricardo was active in the movement, e.g. delivering lectures in local círculos[33] or speaking during rallies like Fiesta de los Martires de la Tradición.[34] In the 1910s the party was increasingly divided between supporters of the claimant Don Jaime and followers of the key theorist, Juan Vázquez de Mella; the points of contention were the question of broad right-wing alliances and Spanish stand during the First World War. All Oreja brothers tended to side with de Mella; when in 1919 the conflict erupted into an open confrontation they decided to abandon the dynastic Jaimista discipline and followed de Mella to build an own organisation.[35]

Before any de Mella party materialized, in 1920 Oreja fielded his candidature to the Cortes. He stood in the Gipuzkoan district of Tolosa and initially was referred to as a Basque nationalist;[36] only later he was identified as a traditionalist of the Mellista breed. The grouping enjoyed much influence in the province and there was no counter-candidate standing; Oreja was declared victorious according to notorious Article 29[37] and entered the legislative as one of two Mellistas.[38] His known activity in the chamber was mostly about the Gipuzkoan paper industry; he advanced its interests with the Diputación[39] and ministerial offices.[40] In 1921 he remained enthusiastic about de Mella and prospects of the party;[41] Oreja accompanied his leader in Madrid[42] and on tours in Catalonia.[43] However, at the time the Mellista structures remained feeble and the movement was influenced by Víctor Pradera, who advocated an alternative, minimalist alliance strategy. Oreja was increasingly bewildered. It is not clear whether he took part in the grand Asamblea de Zaragoza of 1922, already controlled by the Praderistas; representatives of “mellismo ortodoxo” accused him of “imprudencia política tradicionalista”.[44]

At the time Oreja was leaning towards another initiative, formatted as an attempt to launch a Christian-democratic party. Having obtained Pradera's authorization in early 1923 Oreja co-founded Partido Social Popular; together with Salvador Minguijón, Angel Ossorio Gallardo and Manuel Simó Marín he entered its Directorio.[45] In 1923 he renewed his bid for the Cortes mandate; he again stood in Tolosa and again emerged victorious,[46] running on a broad traditionalist ticket;[47] in the chamber he was one of two deputies still associated with increasingly shadowy Mellismo.[48] With other PSP leaders he launched a campaign for fundamental change of the regime, which amounted to doing away with the allegedly obsolete restauración system; in a series of manifestos they advocated proportional electoral system, reform of municipal self-government, and a Catalan autonomy statute.[49] Confronting large sections of the public, they also voiced against the protracted military campaign in Morocco and demanded Spanish withdrawal from the war-engulfed region.[50]

Dictatorship

[edit]

During first weeks following the Primo de Rivera coup Oreja and the PSP leaders remained cautiously supportive of the new military regime. Their manifesto welcomed the dismantling of inefficient, corrupted liberal regime and repeated all earlier reform proposals,[51] accompanied by some new points like institutional support for small property, both urban and rural.[52] In December 1923 the general PSP assembly openly declared full co-operation with directorio militar and proclaimed that support for Primo was a measure of patriotism.[53] However, the dictatorship introduced legislation which rendered regular party activity impossible and PSP operations came to a halt. In mid-1924 Oreja was already noted speaking at rallies of the emergent state quasi-party, Unión Patriótica.[54] He went on with his abogado job, e.g. representing mining companies;[55] he might have been also involved in setup of emerging telecommunications services.[56]

In late 1924 Oreja was first admitted by Alfonso XIII[57] and then nominated civil governor of the Santander province.[58] He served at this role for 26 months, until early 1927.[59] Little is known of his tenure; in historiography it did not attract attention,[60] while contemporary press reported mostly routine duties. Apart from usual admin tasks he was noted as engaged in primoderiverista propaganda[61] and remained busy building the Union Patriótica structures in Cantabria;[62] by virtue of his governor role he presided over the provincial Caridad de Santander.[63] Newspapers hailed him as the administrator who enforced high moral standards and fought pornography.[64] Oreja enjoyed excelled relations with the court and was twice admitted by the ruler in 1926.[65] His photos were published in numerous magazines when in 1926 Alfonso XIII inaugurated the automated Telefónica Nacional phone switchboard by placing a call to Oreja's office in Santander.[66]

When in 1927 Oreja was released from the governor post[67] the press speculated that he would assume some prestigious position in Asamblea Nacional Consultiva, sort of primoderiverista quasi-parliament;[68] however, nothing is known of his appointment. The same year he tried to set up Reformatorio de Menores, a corrective institution for the youth, and started gathering funds,[69] yet it is not clear whether the project bore any fruit. In 1928 he entered executive board of a construction company Agróman, co-founded by his brother Marcelino[70] and specialized in governmental contracts.[71] Some sources claim he was engaged in Sociedad de Estudios Vascos, the institution which promoted Basque culture.[72] Politically he cultivated the Mellista link[73] and approached the circle of Pemán.[74] Following the fall of Primo in 1930 Oreja engaged in Unión Monárquica Nacional, formed part of its secretariado[75] and spoke at some UMN rallies, e.g. in Bilbao.[76] The dictablanda regime initially intended to organize general elections; in early 1931 Oreja was rumored to stand in Tolosa and to compete against a Jaimista candidate, Roman Oyarzun.[77]

Republic

[edit]

Following the fall of the monarchy and emergence of the republic Oreja initially remained on the sidelines of national politics. Unión Monárquica Nacional disintegrated and some of its leaders went on exile; there is no information either on further Oreja engagements in UMN or on his standing in the general elections of June 1931. His only known public role was the leading position in Asociación de Padres de Familia, a lay Catholic pressure group. He presided over numerous meetings, also beyond Madrid,[78] and delivered lectures on dangers of secularization, advanced by the republican government. In practice this campaign boiled down to defense of Catholic schools, incompatible with the new constitution and supposed to disappear.[79] In 1932 Oreja was together with his brother Marcelino – at the time the Cortes deputy - ridiculed by the progressist press as a die-hard reactionary.[80]

After the 1934 assassination of Marcelino Oreja Ricardo provided the account of the event to the press; his communications were very matter-of-fact and he refrained from an emotional, vengeful tone.[81] Ricardo replaced the late Marcelino as business executive in Agróman,[82] though also in Unión Cerrajera, one of the largest Gipuzkoan companies, based in Mondragón; Marcelino had earlier married a daughter of its manager and in the early 1930s he had assumed top administrative duties in Unión himself. The company specialized in metalworking; in 1934 Ricardo assumed presidency of its Consejo de Administración,[83] though daily management of the company was with his brother-in-law José María Agirre Isasi.[84]

First confirmed information on Oreja's return to Carlist engagements is from 1935; early that year he took part in a mass in Madrid, which was about dedication of Secretariado de los Diputados Tradicionalistas to the Sacred Heart of Jesus.[85] Few months later he was noted as far as on Balearic Islands on a Carlist propaganda tour, speaking along such party activists like Luis Arellano, José Lamamie de Clairac and Tomas Quint Zaforteza,[86] and in October numerous traditionalists accompanied him during a mass on a first anniversary of Marcelino's death.[87] In early 1936 Oreja was already regularly engaged in Comunión Tradicionalista events.[88] During general elections of February he appeared as a CT candidate within a joint monarchist alliance of Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria in Gipuzkoa.[89] The list did well, with slightly less votes than the leading PNV one; with 44,769 votes Oreja was the third most-voted candidate in the province.[90] Due to electoral stalemate between PNV, CCR and Frente Popular[91] no list was declared victorious and the second round was needed. However, for reasons which are not clear[92] the monarchists withdrew from the race.[93]

Civil War

[edit]

None of the sources consulted provides information whether Oreja was engaged in the Carlist conspiracy against the republic or whether he was active during the July coup. It is neither clear whether at the outbreak of the Civil War he resided in Vascongadas or in Madrid; it is known that his wife was trapped in the capital. Gipuzkoa was seized by the Nationalists in the late summer of 1936, but there is no data on Oreja until the spring of 1937. In late May of that year the Popular Tribunal of Bilbao, still held by the Republicans, tried him and some other personalities in absentia; they were charged with subversive activities against established legal authorities. Oreja was declared guilty of preparing a military rebellion and sentenced to 20 years imprisonment.[94]

While Oreja's trial was in course in Republican Bilbao, he resided some 40 km away but across the frontline, in the Nationalist-held Gipuzkoan Mondragón. Unión Cerrajera as a large metalworking company which employed some 900 people turned vital for the Nationalist arms industry,[95] and Oreja as president of its board remained heavily engaged in the task of re-shaping the production to suit military needs of the army.[96] His role at the helm of UC translated into important position within the nascent provincial Francoist regime; he remained in touch with Jefé Provincial of the emergent state party Falange Española Tradicionalista and took part in some official acts, like granting the status of tenientes honoriarios to all Carlist veterans from the Third Carlist War.[97]

Until mid-war Oreja did not assume any position within the Nationalist administration and maintained low public profile. It is not clear whether this strategy was related to his wife having been first imprisoned and then held under police surveillance in Madrid. Released from prison in early 1937 she remained in very poor health and was under intense medical care.[98] Officials of the Basque government, including secretariat of the prime minister José Aguirre and the Republican minister of justice Manuel Irujo, were engaged in efforts to issue Carmen Aspiunza a passport and to secure her exit from the Republican zone; it is not identified what backstage mechanism triggered this intervention. However, the minister of interior Julián Zugazagoitia opposed the plan and suggested that Oreja's wife be held in Madrid awaiting a would-be exchange for a Republican figure in Nationalists’ captivity.[99] Eventually, Aspiunza passed away in Madrid in the spring of 1938.[100]

In May 1938 latest Oreja was nominated to the Gipuzkoan Comisión Gestora, a provincial body appointed by the regime and supposed to temporarily replace the dissolved elected self-governmental structure, Diputación Provincial.[101] It is not clear how long Oreja remained within the Comisión; local press provided the related information scarcely and not later than in 1938.[102] He was rather routinely reported as president of Consejo de Administración of Unión Cerrajera;[103] in 1939 he set up Escuela de Aprendices de la Unión Cerrajera, a vocational school operated by the company.[104]

Early Francoism

[edit]During the early post-war period Oreja did not engage in politics. None of the sources consulted notes his activity within the Carlist ranks, be it in the mainstream Javierista current or in the carloctavista and juanista factions. He remained fully aligned with the regime and supported some of its initiatives, e.g. by donating money to División Azul in 1941.[105] In the mid-1940s[106] he was active in Consejo of Confederación de Padres de Familia, nominated to the executive by the Madrid archbishop.[107] At least until the end of the decade he remained engaged also in Junta Madrileña of Patronato de Protección a la Mujer and in Patronato de Formación Profesional y Obrera.[108] The latter later evolved into Acción Social Patronal, a Catholic organisation in-between a trade union, a think-tank, a lobbying group, a charity organisation, an educational institution and a mutual help association; Oreja held a seat in its Comisión Nacional.[109] Though he returned to Madrid Oreja kept serving as president of Unión Cerrajera, which posed some problems in practical terms.[110]

In 1948 Oreja decided to take part in the first municipal elections under Francoism and to run for the Madrid ayuntamiento. He fielded his candidature in a curia named tercio familiar[111] and formed a list of technocratic professionals, headed by Luis Calvo Sotelo;[112] with 107,835 votes he was comfortably elected.[113] At unspecified time but prior to 1951 he was nominated the deputy mayor; in the council he was responsible for so-called Cuarta Zona and headed Comisión de Hacienda.[114] Following 3 years of service with great fanfare he received homage from other members of the city council.[115] At the time he was employed in Tribunal Económico Administrativo Central, a regulatory body within the ministry of economy.[116]

In 1951 Oreja was admitted at a personal audience by Franco; the subject of their meeting has not been disclosed.[117] It might have been related to Oreja's ascendance to a high governmental job; the same year he was nominated sub-secretario, effectively the deputy minister, in Ministerio de Justicia,[118] just assumed by another fellow ex-Carlist Antonio Iturmendi. However, he stayed clear of independent Carlist politics and remained firmly within the limits of loyalty to caudillo; the only Traditionalist feature he permitted himself was cultivating of the Vázquez de Mella memory.[119] In 1952 he was again admitted by Franco[120] and received Gran Cruz del Mérito Civil.[121] Also in 1952 he received his Cortes mandate from the pool of Franco's personal appointees;[122] In the chamber Ricardo joined his brother Benigno, who had served three earlier terms since 1943. In 1954 Oreja's term in the Madrid ayuntamiento came to an end.[123]

Mid- and late Francoism

[edit]

In the mid-1950s Oreja reached the regular retirement age. One source claims that in 1955 he ceased as president of Consejo de Administración of Unión Cerrajera,[124] though another one suggests that he performed some roles in the company, possibly as an honorary president, during the following 20 years. At the time the company employed 1,700 people and was the largest industrial enterprise in Gipuzkoa.[125] Some authors claim that the year of 1956, the first one after his resignation, was the turning point for the company and the moment it entered the downward path.[126] In 1955 the primate nominated him vice-president of Consejo de Confederación Católica Nacional de Padres de Familia.[127] Oreja was also active as vice-president in a conservative think-tank Instituto Histórico-Jurídico Francisco Suarez, in the late 1950s renamed to Asociación International Francisco Suarez;[128] as such he at times delivered lectures at various ateneos.[129] Círculo Cultural Juan Vázquez de Mella, a quasi-political Traditionalism-flavored chain freshly permitted by the regime, declared him an honorary member in 1959.[130]

Oreja was repeatedly re-appointed to the Cortes, always from the pool of personal Franco's appointees, in 1955,[131] 1958,[132] 1961[133] and 1964.[134] Little is known about his labors in the chamber except some role in a commission working on Ley de Principios del Movimiento Nacional, the law which thwarted the last Falangist attempt to convert the regime into a totalitarian system.[135] His term commenced in 1964 was to expire in 1967, but in 1965 and aged 75 Oreja resigned the mandate.[136] The same year he terminated his 14-year-long service as subsecretario de justicia.[137] Little is known of his role in the ministry.[138] The press reported of his routine official duties, like homage to civil war combatants,[139] openings of new institutions[140] or giving lectures.[141] Historiographic works suggest at various points he supervised religious issues,[142] prisons,[143] and juvenile crime.[144] He received a number of orders,[145] the most prestigious one having been Gran Cruz de San Raimundo de Peñafort.[146] His traditionalist penchant was demonstrated only when fully integrated within the Francoist ideology,[147] e.g. when meeting ex-requetés, lecturing about Vázquez de Mella or taking part in the official version of the Martires de la Tradición feast.[148]

During late Francoism Oreja mostly withdrew into privacy and was barely active in public, e.g. in 1967 he was noted as the former Ministry of Justice official present during opening of a new ministerial building, the construction of which he reportedly had initiated.[149] He was well established within the regime top strata and within the Basque industrial oligarchy alike; the list of guests at various family events he attended reads like a report from an official or industry ceremony.[150] The last moment he appeared in politics occurred in 1969; as the regime expulsed a progressist carlohuguista pretendent prince Carlos Hugo, the administration was eager to demonstrate that caudillo enjoyed unlimited Carlist support. Oreja headed a group of former Carlist deputies[151] admitted by the dictator who declared their full loyalty to Franco and to the regime; the event received wide public coverage.[152]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ according to Marcelino Oreja Aguirre, Antecedentes de la Revolución de octubre de 1934 y su repercusión en el País Vasco, [in:] Euskonews service 2011, available here

- ^ José María Urkia Etxabe, Benigno Oreja, pionero de la Urología en Euskadi, [in:] Noticias de Gipuzkoa, 15.10.14

- ^ he married Getrtudis Echániz Urquiaga, see Martin Oreja Arzadun entry, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ Boletin de Medicina, Cirurgía y Farmacia 19.03.48, available here

- ^ Boletin de Medicina, Cirurgía y Farmacia 24.08.51, available here

- ^ Basilio Oreja Echaniz entry, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ he is first time mentioned in Anuario-almanaque del comercio, de la industria, de la magistratura y de la administración (1879), p. 1215, available here

- ^ Oreja Echaniz was listed as alcalde in 1900 and 1902, compare Annual del comercio, de la industria, de la magistratura y de la administración (1900), p. 545, available here

- ^ Cecilia Elósegui Ayala entry, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ Urkia Etxabe 2014

- ^ Florencio (1882-1884) and Pascual (1888-1890), see Cecilia Elósegui Ayala entry, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 03.02.08, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 19.04.10, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 02.03.12, available here

- ^ Mundo Gráfico 20.03.12, available here

- ^ certificate issued by Colegio de Abogados de Madrid 11.07.21, available here Archived 2021-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 09.11.12, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de España 18.04.16, available here

- ^ La Mañana 23.05.16, available here

- ^ La Epoca 05.06.16, available here

- ^ La Tierra de Segovia 24.05.19, available here

- ^ see certificate issued by Jefe del Registro Central de Penados y Rebeldes within Direccion General de Prisiones, 14.07.21, [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid available here

- ^ certificate issued by Colegio de Abogados de Madrid, 11.07.21, [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid available here

- ^ El Debate 08.02.19, available here

- ^ Movimiento Nobiliario 1931-1940, p. 83, available here

- ^ first at Calle Marques del Duero 6, see here, and then at Calle Serrano 20, Madrid Automóvil May 1928, available here

- ^ Movimiento Nobiliario 1931-1940, p. 83, available here

- ^ El Pueblo Cantabro 23.09.25, available here

- ^ ABC 29.07.51, available here

- ^ Eduardo Jordá López, 75. Aniversario. Historia de SECOT, Madrid 2010, p. 35

- ^ Fernando Oreja Aspiunza married María Teresa Igartúa Acha, ABC 16.06.54, available here

- ^ ABC 04.04.74, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 03.02.08, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 21.03.08, available here

- ^ José Luis Orella Martínez, El origen del primer Catolicismo social Español [PhD thesis, Universidad de Educación a Distancia], Madrid 2012, p. 182

- ^ La Voz 10.12.20, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1920 mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de España 13.12.20, available here, Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista: historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820, p. 211

- ^ La Voz 22.01.21, available here

- ^ La Voz 16.03.21, available here

- ^ Oreja declared “soy un entusiasta, un optimista, pues con un hombre que es la encarnación del talento, de la abnegación y del sacrificio, que enarbola una bandera de principios sagrados, no se puede sentir nunca el desaliento”, referred after Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 221-222

- ^ La Epoca 04.06.21, available here

- ^ Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 221-222

- ^ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 241

- ^ La Correspondencia de España 10.01.23, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1923 mandate at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia de España 30.04.23, available here

- ^ Andrés Martín 2000, p. 242

- ^ La Voz 08.07.23, available here

- ^ El Sol 07.02.23, available here

- ^ El Sol 02.10.23, available here

- ^ La Acción 08.12.23, available here

- ^ El Debate 21.12.23, available here

- ^ El Debate 05.06.24, available here

- ^ El Debate 29.05.24, available here

- ^ see a note in El Orzán 15.11.24, available here, which suggests that Oreja had some business links with the telecom industry

- ^ El Sol 17.12.23, available here

- ^ La Epoca 10.12.23, available here

- ^ La Voz 15.02.27, available here

- ^ except work on Museo Prehistorico in Santander; Oreja supported its emergence, Ignacio Castanedo Tapia, Virgilio Fernandez Acebo, El manuscruto ‘Museo Prehistórico de Santander’ de Jesús Carballo, Santander 2019, pp. 7, 9

- ^ El Cantábrico 27.04.26, available here

- ^ La Región 25.06.26, available here

- ^ La Montaña 10.12.26, available here

- ^ Revista católica de las cuestiones sociales February 1925, available here

- ^ La Correspondencia Militar 02.03.26, available here, also La Nación 10.06.26, available here

- ^ Nuevo Mundo 03.09.26, available here, La Esfera 04.09.26, available here

- ^ El Imparcial 27.02.27, available here

- ^ El Pueblo Cantabro 28.01.27, available here

- ^ El Cantábrico 29.03.27, available here

- ^ Oreja Aguirre 2011

- ^ e.g. Agróman was contracted for refurbishment works at Universidad Central, see ABC 24.07.30, available here

- ^ Oreja Elósegui, Ricardo, [in:] Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia, available here, Idioia Estornés Zubizarreta, La Sociedad de Estudios Vascos. Aportación de Eusko Ikaskuntza a la Cultura Vasca, Donostia 1983, ISBN 848624000X, p. 60. Details of his alleged engagement in SEV are not clear. It is confirmed that Oreja at least donated money to SEV, for 1928 see Eusko-Ikaskuntza 1926-1928, San Sebastián 1929, p. 46

- ^ in 1928 Oreja was in Comisión ejecutiva of Junta Organizadora which prepared ceremonies related to de Mella’s funeral, El Debate 03.06.28, available here. In 1929 Oreja appeared at homage to Vazquez de Mella organized on the first anniversary of his death, El Imparcial 27.02.29, available here

- ^ in 1929 Oreja attended a banquet intended as homage to Pemán, La Nación 05.11.29, available here

- ^ La Epoca 15.04.30, available here

- ^ La Nación 06.01.30, available here

- ^ El Debate 12.02.31, available here

- ^ e.g. in Ciudad Real, see La Nación 07.06.32, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia [Manila] 02.08.32, available here

- ^ Luz 14.06.32, available here

- ^ La Nación 18.10.34, available here

- ^ since 1933 he started to appear as “personal técnico” of Agróman, “empresa constructora”, Guadalquivir March 1933, available here

- ^ Unión Cerrajera, [in:] Eusko Auñamendi Entziklopdia, available here, see also El Financiero 19.08.35, available here

- ^ Agirre was brother to Marcelino's wife, Josemari Velez de Mendizabal, José Ángel Barrutiabengoa, Juan Ramón Garai, “Ama” Cerrajera, Donostia 2007, p. 92

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 15.02.34, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 30.04.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 09.10.35, available here

- ^ e.g. in January 1936 Oreja attended a mass to honor the claimant Alfonso Carlos; the accompanying evening event was presided by Manuel Fal Conde, El Siglo Futuro 23.01.36, available here

- ^ the campaign slogans of Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria were ¡Por Dios y por la Patria! ¡Por el orden, por la paz y por la justicia social! ¡Pos las víctimas de octubre! ¡A votar contra la revolución y sus cómplices!, El Nervión 03.02.36, available here

- ^ the leading contender Manuel Irujo (PNV) gathered 47,492 votes, José Múgica (Renovación Española) gathered 45,743 votes, and Oreja gathered 44,759 votes, El Nervión 17.02.36, available here

- ^ average votes gathered by 3 competing lists were PNV 48,912, CCR 43,694, FP 40,033, José Luis de la Granja Sainz, Nacionalismo y II República en el País Vasco: Estatutos de autonomía, partidos y elecciones. Historia de Acción Nacionalista Vasca, 1930-1936, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788432315138, p. 591

- ^ the Candidatura Contrarrevolucionaria contenders published an open letter, which in very vague and ambiguous terms discussed the withdrawal, El Siglo Futuro 29.02.36, available here. The decision was probably related to a pastoral letter of bishop of Vitoria, who declared that PNV and CCR were equally Catholic, La Nación 28.02.36, available here

- ^ Ahora 28.02.36, available here

- ^ La Libertad 26.05.37, available here

- ^ Unión Cerrajera, [in:] Eusko Auñamendi Entziklopdia, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 01.06.37, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 15.03.38, available here

- ^ see Fondo Irujo, [in:] Eusko Ikaskuntza digital archive, available here. At the same address there was also a "Fernando Ortiz Aspiunza", a boy of 11 years, reported as resident. This might be a typo and the person in question might have been Oreja's son, Fernando Oreja Aspiunza, born 1925.

- ^ on August 30, 1937, Zugazagoitia wrote to Irujo: "“cabe esperar que esta señora, a cuya evacuación no me opondre en ningún caso, pueda servir para canjearla por alguna compañera nuestra. Me parece que nos pierde demasiado la blandenguería. Esta señora vive por efecto de inyecciones, según se dice an la carta del Presidente del Gobierno vasco, pero esa situación le envidiarían muchas compañeras mías que ya no pueden vivir ni con inyecciones ni sin ellas por haberlas ejecutado los facciosos. A mi juicio procedería que esta señora fuera tenida en cuenta por el Ministerio de Estado para ofrecerla en canje por alguna otra persona que pueda interesarnos”, see Fondo Archivo Histórico del Gobierno Vasco. Fondo del Departamento de Presidencia, [in:] Dokuklik Euskadi service, available here

- ^ Movimiento Nobiliario 1931-1940, p. 83, available here

- ^ Oreja Elósegui, Ricardo entry, [in:] Eusko Auñamendi Entziklopedia, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 02.06.38, available here

- ^ Velez, Barrutiabengoa, Garai 2007, p. 92

- ^ Ana Cuevas Badallo, Obdulia Torres González, Rodrigo López Orellana, Daniel Labrador Montero, Cultura científica y cultura tecnológica: Actas del IV Congreso Iberoamericano de Filosofía de la Ciencia y la Tecnología, Salamanca 2018, ISBN 9788490129111, p. 24; Velez, Barrutiabengoa, Garai 2007, p. 77

- ^ ABC 18.11.41, available here

- ^ El Adelanto 18.09.43, available here

- ^ ABC 30.11.44, available here

- ^ ABC 24.04.49, available here

- ^ José Andrés-Gallego, Antón M. Pazos, La Iglesia en la España contemporánea, Madrid 1999, ISBN 9788474905205, p. 92

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 21.09.45, available here. Compare a later anecdote featuring Agirre, who travelled to Madrid to speak to Oreja; when their conversation was 3 times interrupted by phone calls he concluded that "perhaps I will return to Mondragon and have a phone chat with you"

- ^ ABC 11.12.51, available here

- ^ ABC 23.11.48, available here

- ^ ABC 19.11.48, available here

- ^ ABC 29.07.51, available here

- ^ ABC 01.12.51, available here

- ^ ABC 29.07.51, available here

- ^ ABC 16.11.51, available here

- ^ ABC 31.07.51, available here

- ^ in 1953, on the 25th anniversary of de Mella’s death, Oreja attended a related ceremony, ABC 27.02.53, available here

- ^ ABC 20.11.52, available here

- ^ ABC 06.01.52, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1952 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ ABC 16.11.54, available here

- ^ Velez, Barrutiabengoa, Garai 2006, p. 92

- ^ ABC 04.06.74, available here

- ^ Josemari Velez de Mendizabal Azkarraga, Unión Cerrajera S.A., un patrimonie de cien años, [in:] Euskonews service 2006, available here

- ^ ABC 01.05.55, available here

- ^ ABC 30.12.55, available here

- ^ see e.g. his lecture in the Barcelona Ateneo, ABC 06.02.57, available here

- ^ ABC 11.11.59, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1955 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1958 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1961 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ see Oreja’s 1965 ticket at the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Sigfredo Hillers de Luque, España: Régimen jurídico-político de Franco (1936-1975) versus Régimen político actual de Juan Carlos I/Felipe VI (partitocracia coronada), Madrid 2015, ISBN 9781463370114, p. 112

- ^ ABC 22.09.65, available here

- ^ for his release note see BOE 174 (1965) 22.07.1965, p. 10347

- ^ a particularly puzzling episode is Oreja's intervention in favor of Jesus Navarro, a petty criminal involved in the killing of a prostitute Carmen Broto, La Vanguardia 26.03.91, available here. The murder gained nationwide attention as links to politics, religion and business were widely suspected, with many prestigious personalities intervening so that Navarro's death penalty is changed to lifetime incarceration

- ^ ABC 10.07.56, available here

- ^ ABC 13.10.60, available here

- ^ ABC 21.06.61, available here

- ^ in 1963 Oreja was engaged against Catholic scouting in Catalonia; the ministry had some misgivings about its independent position and Catalanist threads, Josep Clara, Ripoll 1963: contrentració escolta i teatre polític. “Manifestaciones inadmisibles contra la unidad nacional”, [in:] Butlleti de la Societat Catalana d’Estudis Histórics XXVI (2015), p. 238

- ^ Josep Clara, El bisbe Narcís Jubany contra les clarisses de salt, [in:] Annals de l’Institut d’Estudis Gironins LVII (2016)p. 276

- ^ International Child Welfare Review 16 (1962), p. 216

- ^ ABC 07.02.61, available here

- ^ ABC 24.01.58, available here

- ^ however, until 1968 Oreja maintained private correspondence with Manuel Fal Conde, see catalogue of Fondo Manuel Fal Conde, [in:] Universidad de Navarra archive, p. 214, available here

- ^ ABC 11.03.62, available here; mainstream Carlists used to stage their own version of the event, in the late 1960s increasingly formatted in anti-Franco terms

- ^ ABC 10.12.67, available here

- ^ ABC 08.01.71, available here

- ^ with Together with Romualdo de Toledo, Zamanillo, Oriol (JL), Carcér and Ramírez Sinues,

- ^ Diario de Burgos 27.03.69, available here, also ABC 27.03.69, available here

Further reading

[edit]- Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista: historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820

- Sharryn Kasmir, The Myth of Mondragon. Cooperatives, Politics and Working-Class Life in a Basque Town, New York 1996, ISBN 0791430030

- Josemari Velez de Mendizabal, José Ángel Barrutiabengoa, Juan Ramón Garai, “Ama” Cerrajera, Donostia 2007

External links

[edit]- Businesspeople from the Basque Country (autonomous community)

- Carlists

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Corporatism

- Education activists

- Spanish far-right politicians

- Madrid city councillors

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Spanish Restoration

- Members of the Cortes Españolas

- People from Busturialdea

- Politicians from Cantabria

- Politicians from Madrid

- Politicians from the Basque Country (autonomous community)

- Regionalism (politics)

- Roman Catholic activists

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish civil servants

- Spanish jurists

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish municipal councillors

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- University of Valladolid alumni

- 20th-century Spanish businesspeople