Religion in Zimbabwe

Religion in Zimbabwe (2017)[1]

Christianity is the most widely professed religion in Zimbabwe, with Protestantism being its largest denomination.[2]

According to the 2017 Inter Censal Demography Survey by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 69.2 percent of Zimbabweans belong to Protestant Christianity, 8.0 percent are Catholic, in total 84.1 percent follow one of the denominations of Christianity.[1][3] Traditional religions are followed by about four percent, and unspecified and none eight percent. The other major religions of the world such as Islam (0.7%), Buddhism (<0.1%), Hinduism (<0.1%) and Judaism (<0.1%) each have a niche presence.

While the country is majority Christian, in the early 2000s, most people also practiced, to varying degrees, elements of the indigenous religions;[4] religious leaders also reported an increase in adherence to traditional religion and shamanic healers.

The Constitution of Zimbabwe allows for freedom of religion.[5] In 2023, the country was scored 3 out of 4 for religious freedom.[6]

Christianity

[edit]

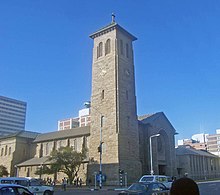

The first Christian mission arrived in Zimbabwe in 1859 because of the efforts of London Missionary Society.[7] Their work began among the Zulu people. David Livingstone appealed to the British government to assign land and protection to Christian missions, which led to a land grant to the Universities Mission in 1888 and the center of missionary activity to the Zulu and Shona peoples.[7] The first Methodist mission arrived in 1896, with members from the United Kingdom and the United States. The British worked with the white settlers, while the Americans worked with the native Africans. The Seventh-Day Adventists and Central African Christian Mission established their missions in 1890s.[7][8] Pentecostalism and African Apostolic Churches arrived in the 1920s, and grew rapidly, with the Zion Christian Church now the largest Protestant following in Zimbabwe.[8] In 1932, Johane Marange (born: Muchabaya Momberume) announced that he had received vision and dream to preach like John the Baptist, an apostle. He baptized many in a local river, and his efforts in the decades that followed led to African Apostolic Church, the second largest ministry in Zimbabwe.[8][9]

Most Zimbabweans Christians are Protestants. The Protestant Christian churches with large membership are Anglican (represented by the Church of the Province of Central Africa), Seventh-day Adventist[10] and Methodist.[11]

There are about one million Roman Catholics in the country (about 7% of the total population).[12] The country contains two archdioceses (Harare and Bulawayo), which each contain three dioceses Chinhoyi, Gokwe, and Mutare; and Gweru, Hwange, and Masvingo; respectively). The most famous Catholic churchman in Zimbabwe is Pius Ncube, the archbishop of Bulawayo, an outspoken critic of the government of Robert Mugabe, who was also Roman Catholic.

A variety of local churches and groups have emerged from the mainstream Christian churches over the years that fall between the Protestant and Catholic churches. Some, such as the Zimbabwe Assemblies of God, continue to adhere to Christian beliefs and oppose the espousal of traditional religions. In the early 2009s, other local groups, such as the Seven Apostles, combined elements of established Christian beliefs with some beliefs based on traditional African culture and religion.[13]

Traditional religions

[edit]About four percent of Zimbabweans express their religion to be Traditional, but most Christians continue to practice elements of their traditional religions. Further, most Zimbabwe churches, like African Churches, now incorporate worship practices that include traditional African rituals, songs, dance, non-Christian iconography and oral culture.[8]

Islam

[edit]

Islam is the religion of less than one percent of the population of Zimbabwe.[3] The Muslim community consists primarily of South Asian immigrants (Indian and Pakistani), a small number of indigenous Zimbabweans, and a very small number of North African and Middle Eastern immigrants. There are mosques located in nearly all of the larger towns. There are 18 in the capital city of Harare, 8 in Bulawayo, and a number of mosques in small towns. The mosques and proselytization effort is financed with the aid of the Kuwaiti-sponsored African Muslim Agency (AMA)[14]

Bahá'í Faith

[edit]Bahá'í was brought to Zimbabwe in 1929 by Shoghi Effendi, then Guardian of the religion.[15] In 1953 several Bahá'ís settled in what was then Southern Rhodesia.[16] The first Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assembly was formed in Harare.[15] By the end of 1963 there were 9 assemblies.[17] While still a colony of the United Kingdom, the Bahá'ís nevertheless organised a separate National Spiritual Assembly in 1964.[18] The National Assembly has continued since 1970.[16] In 2003, the 50th anniversary of the Bahá'ís in Zimbabwe, a year of events across the country culminated with a conference of Bahá'ís from all provinces of Zimbabwe and nine countries. There were 43 local spiritual assemblies in 2003.[15]

Hinduism

[edit]There are small number of Hindus in Zimbabwe. Hindus are mainly concentrated in the capital city of Harare. Hindu Society mainly consists of Gujaratis, Goan and Tamil. Hindu Primary and Secondary schools are found in the major urban areas such as Harare and Bulawayo.[19][20][21][22]

Brahma Kumaris have two Centres in Zimbabwe in 2023 (in Harare and Bulawayo).[23] ISKCON has a Centre at Marondera. Ramakrishna Vedanta Society has a centre in Harare.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Inter Censal Demography Survey 2017 Report, Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (2017)

- ^ "Africa: GUINEA-BISSAU, People and Society". CIA The World Factbook. 2011.

- ^ a b Religious composition by country, Pew Research, Washington DC (2012)

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Zimbabwe. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ US State Dept 2022 report

- ^ Freedom House website, retrieved 2024-02-05

- ^ a b c J. Gordon Melton (2005). Encyclopedia of Protestantism. Infobase. pp. 594–595. ISBN 978-0-8160-6983-5.

- ^ a b c d Alister E. McGrath; Darren C. Marks (2008). The Blackwell Companion to Protestantism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 474–476. ISBN 978-0-470-99918-9.

- ^ Charles E. Farhadian (16 July 2007). Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 50, 66–70. ISBN 978-0-8028-2853-8.

- ^ "Adventist Atlas website, Zimbabwe page". Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ "Church in Zimbabwe far behind in communication". Archived from the original on 2008-06-06. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ Statistics relating to the Catholic church in Zimbabwe

- ^ US State Dept 2009, Religion in Zimbabwe This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ James Gow; Funmi Olonisakin; Ernst Dijxhoorn (2013). Militancy and Violence in West Africa: Religion, politics and radicalisation. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-135-96857-1.

- ^ a b c Bahá'í International Community (2003-12-12). "Drumming and dancing in delight". Bahá'í International News Service.

- ^ a b "History of the Zimbabwean Community". The Bahá'í Community of Zimbabwe. National Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Zimbabwe. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land (1964). The Bahá'í Faith: 1844-1963, Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Bahá'í Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963. Israel: Peli - P.E.C. Printing World LTD.Ramat Gan. p. 114.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. p. 629. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ The Hindoo Society Newsletter Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, Harare, Zimbabwe; Current Archives Archived 2016-12-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Modern Temple Rises Out of Zimbabwe Soil Archived 2019-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Hinduism Today (1991)

- ^ The Hindoo Society Archived 2019-01-22 at the Wayback Machine, Harare, Zimbabwe, Official Website

- ^ *Hindus in Zimbabwe Archived 2007-04-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brahma Kumaris Centres in Zimbabwe, retrieved 2023-08-08

Further Reading (Ezra Chitando, Prophets, profits and the Bible in Zimbabwe) [1]

External links

[edit]- Religion in Zimbabwe - RelZim news portal

- ZJC Project on the history of the Zimbabwe Jewish Community

- ^ Chitando, Ezra; Gunda, Masiiwa Ragies; Kugler, Joachim (2013). Prophets, profits and the Bible in Zimbabwe. University of Bamberg. ISBN 9783863091989.