Presidency of Ernesto Geisel

| |

| Presidency of Ernesto Geisel 15 March 1974 – 15 March 1979 | |

Vice President | |

|---|---|

| Party | ARENA |

| Election | 1974 |

|

| |

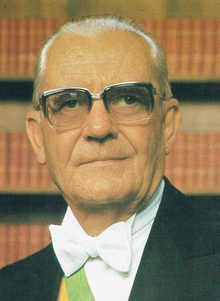

The presidency of Ernesto Geisel began with the inauguration of General Ernesto Geisel as President of the Republic on March 15, 1974 and ended on March 15, 1979 when General João Figueiredo took office.[1]

Ernesto Geisel was the fourth president of Brazil's military dictatorship. During his government, the country's process of re-democratization began, Guanabara was annexed to Rio de Janeiro, the state of Mato Grosso was divided into Mato Grosso do Sul and the Brazilian Miracle and Institutional Act Number Five were abolished.[1]

The administration of Ernesto Geisel was marked by growth of 31.88% in GDP (an average of 6.37%) and 19.23% in per capita income (an average of 3.84%). However, growth slowed after the 1973 Oil Crisis. Geisel took office with inflation at 15.54% and handed over at 40.81%.[1][2]

The president

[edit]Ernesto Geisel began his career in 1921 as a student at the Military College in Porto Alegre and reached his most important political positions during the 1964 military regime as head of the Military Cabinet in the Castelo Branco government and minister of the Superior Military Court in the Costa e Silva administration. He was president of Petrobrás when he was nominated by President Médici as a candidate to succeed him on June 18, 1973.[3]

A month later, he resigned from Petrobrás and was endorsed as a candidate for President of the Republic at ARENA's national convention on September 14; his vice-presidential partner was General Adalberto Pereira dos Santos. On January 15, 1974, they beat the MDB team formed by Ulysses Guimarães and Barbosa Lima Sobrinho by a score of 400 votes to 76 in the first election held by an Electoral College. Geisel was sworn in at a solemn session of the National Congress chaired by Senator Paulo Torres (ARENA-RJ). He followed the moderate line of the armed forces, as he saw the military regime as a transitional measure to ensure liberalism in the country.[Note 1][Note 2][3][4][5]

Ministers and assistants

[edit]Ministers of State

[edit]| Ministry | Responsible | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Justice | Armando Ribeiro Falcão | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of the Navy | Geraldo Azevedo Henning | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of the Army | Vicente de Paulo Dale Coutinho | March 15, 1974 to May 27, 1974 |

| Sílvio Couto Coelho da Frota | May 28, 1974 to October 12, 1977 | |

| Fernando Belfort Bethlem | October 12, 1977 to March 15, 1979 | |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | Antônio Francisco Azeredo da Silveira | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Finance | Mário Henrique Simonsen | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Transportation | Dirceu Araújo Nogueira | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Agriculture | Alysson Paulinelli | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Education and Culture | Ney Amintas de Barros Braga | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Labor and Social Security | Arnaldo da Costa Prieto | March 15, 1974 to May 2, 1974 |

| Ministry of Labor | May 2, 1974 to March 15, 1979 | |

| Ministry of Aeronautics | Joelmir Campos de Araripe Macedo | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Health | Paulo de Almeida Machado | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Industry and Trade | Severo Fagundes Gomes | March 15, 1974 to February 8, 1977 |

| ngelo Calmon de Sá | February 9, 1977 to March 15, 1979 | |

| Ministry of Mines and Energy | Shigeaki Ueki | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Planning and General Coordination | João Paulo dos Reis Veloso | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of the Interior | Maurício Rangel Reis | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Communications | Euclides Quandt de Oliveira | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

| Ministry of Welfare and Social Assistance | Arnaldo da Costa Prieto | May 2, 1974 to July 4, 1974 (cumulatively) |

| Luís Gonzaga do Nascimento e Silva | July 4, 1974 to March 15, 1979 |

Advisory bodies

[edit]| Ministry | Responsible | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Military Office | Hugo de Andrade Abreu | March 15, 1974 to January 6, 1978[Note 3] |

| Gustavo Morais Rego Reis | January 6, 1978 to March 15, 1979 | |

| Civil Cabinet | Golbery do Couto e Silva | March 15, 1974 to March 15, 1979[Note 3] |

| National Information Service | João Batista de Oliveira Figueiredo | March 15, 1974 to June 14, 1978 |

| Armed Forces General Staff | Humberto de Sousa Melo | March 15, 1974 to September 27, 1974[Note 3] |

| Antônio Jorge Correia | October 4, 1974 to August 3, 1976 | |

| Moacir Barcelos Potiguara | August 5, 1976 to October 27, 1977 | |

| Tácito Teófilo Gaspar de Oliveira | October 27, 1977 to December 19, 1978 | |

| José Maria de Andrada Serpa | December 20, 1978 to March 15, 1979 |

Political actions

[edit]

Ernesto Geisel assumed office after promising a "slow, gradual and secure" political opening in order to meet the demands of organized civil society without interrupting the regime. During his administration, there were fewer complaints about the death, torture and disappearance of political prisoners and confrontation with the hardline, a group opposed to the government's directives. Institutional Act Number Five was used to decree federal intervention in Rio Branco in 1975 after the MDB councillors refused to ratify the mayoral nominee and to remove some parliamentarians from office. AI-5 was progressively replaced by "constitutional safeguards".[5][1][6]

In the campaign for the 1974 elections, MDB candidates won sixteen of the twenty-two seats in the Federal Senate and increased their representation in the Chamber of Deputies and the Legislative Assemblies. Fearing that this would happen again, in 1978 the government sanctioned the Falcão Law, which only allowed candidates' CVs to be read out during election time on radio and television.[Note 4][7][8]

On April 8, 1977, the Pacote de Abril (English: April Package) was approved and included an increase in the presidential term from five to six years, the creation of the two-year senator, the maintenance of indirect elections for governor and an increase in the number of federal deputies in the states where the government had a majority. The measures prompted criticism from the opposition, but ensured the election of General João Figueiredo as Ernesto Geisel's successor on October 15, 1978. On December 31, Institutional Act Number Five was revoked.[9][10]

After the deaths of journalist Vladmir Herzog and worker Manuel Fiel Filho in the DOI-CODI, also known as DOPS, between October 1975 and January 1976, the government was forced to curb the actions of the hardliners. This culminated in the replacement of General Sylvio Frota by General Fernando Belfort Bethlem in the Ministry of the Army, as a result of criticism of the High Command of the Armed Forces and the General Command of the National Information System (SNI) for allowing infiltrators to destroy important files on the premises of regional organizations. The measure represented a victory against the "radical" sectors of the Armed Forces. The Geisel government also experienced bomb attacks on the Brazilian Press Association, the Order of Attorneys of Brazil, the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning and the residence of journalist Roberto Marinho.[11][12]

During the Geisel government, the states of Rio de Janeiro and Guanabara merged, the state of Mato Grosso do Sul was created and former presidents Eurico Gaspar Dutra, Ranieri Mazzilli, Juscelino Kubitschek and João Goulart died.[1][13]

Society

[edit]The Divorce Law was sanctioned on December 26, 1977, following the adoption of a simple majority quorum for the approval of constitutional amendments. The inclusion of divorce had been a cause defended by Nelson Carneiro for years.[Note 5][14]

Economic overview

[edit]The Geisel government was marked by the end of the Brazilian Miracle, the 1973 Oil Crisis and an increase in both inflation and external debt. To overcome the obstacles, the government decided to draw up the Second National Development Plan and instituted the National Alcohol Program in order to diversify the energy matrix. Construction began on the Itaipu Hydroelectric Power Plant in partnership with Paraguay and a contract with Bolivia to supply gas to Brazil was signed in 1974. The following year, a nuclear agreement was signed with the then West Germany.[1][15][16][17][18]

Due to the rise in the cost of living and inflation, workers began to organize and protest more emphatically. As a result, the trade union movement in the Greater ABC region gained prominence and the figure of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was projected nationally. The repercussions of the movement led the government to ban strikes in essential sectors.[1][19][20]

Foreign relations

[edit]Brazil established diplomatic relations with China and with Eastern European countries such as Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania, and was the first nation to recognize Angola's independence. Relations with the United States were cut during the Jimmy Carter administration after accusations of human rights violations. Geisel strengthened diplomatic ties with China and reached a nuclear agreement with Germany.[1][21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Federal deputies José Maria Alkmin, Oscar Pedroso Horta and Stélio Maroja were absent from the vote for health reasons, while Fernando Gama, Jerônimo Santana and Nadyr Rossetti did not vote for the MDB candidates.

- ^ The choices of Castelo Branco, Costa e Silva and Emílio Médici were made by the National Congress, the last two already under bipartisanship and without the participation of the MDB.

- ^ a b c As of May 2, 1974, the holder of the post was granted the status of Minister of State.

- ^ The law, sanctioned under the number 6.339 on July 1, 1976, was named after its creator, the then Minister of Justice Armando Falcão.

- ^ Originally, divorce was included in Constitutional Amendment No. 9 of June 28, 1977.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Ernesto Geisel". UOL. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "GDP growth (annual %) - Brazil". The World Bank. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ a b "GEISEL, Ernesto". FGV. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Oliveira, Dante (2013). "Dante de Oliveira: ensaio biográfico e seleção de discursos". Edições Câmara (69).

- ^ a b "Abertura Política". InfoEscola. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "Discurso proferido na transmissão do poder". Federal Government of Brazil. Retrieved 2024-01-05.

- ^ "Lei Falcão faz 30 anos". Agência Senado. 2006-07-03. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Oliveira, Guilherme (2016-10-17). "Há 40 anos, Lei Falcão reduzia campanha eleitoral na TV a 'lista de chamada'". Agência Senado. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Paganine, Joseana (2017-03-31). "Há 40 anos, ditadura impunha Pacote de Abril e adiava abertura política". Agência Senado. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Koerner, Andrei (2018). "Um supremo coadjuvante: a reforma judiciária da distensão ao Pacote de Bril de 1977". CEBRAP. 37 (1).

- ^ Carneiro, Paulo Luiz (2016-01-13). "Morte do operário Manuel Fiel no DOI-Codi, em 1976, precipita abertura política". O Globo. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Reina, Eduardo (2022-01-08). "Ditadura no Brasil: EUA previam que Figueiredo poderia renunciar à Presidência, revelam documentos inéditos". BBC. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "Lista com todos os presidentes do Brasil". UOL. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "LEI Nº 6.515, DE 26 DE DEZEMBRO DE 1977". Federal Government of Brazil. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "Proálcool". UOL. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Maringoni, Gilberto (2016-11-23). "A maior e mais ousada iniciativa do nacional‑desenvolvimentismo". IPEA. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ "Decreto nº 76.593, de 14 de Novembro de 1975". Federal Government of Brazil. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Maciel, João Vitor (2017). "II PND: o desenvolvimento brasileiro segundo a teoria da dependência" (PDF). UFRJ.

- ^ "As greves no ABC e o fim da ditadura". UOL. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

- ^ Ramalho, José Ricardo; Rodrigues, Iram (2018). "Sindicalismo do ABC e a era Lula: contradições e resistências". Lua Nova (104): 67–96. doi:10.1590/0102-067096/104.

- ^ Lima, Sérgio Eduardo; Villafañe, Luis Claudio (2015). "Quarenta anos das relações Brasil-Angola : documentos e depoimentos". FUNAG.