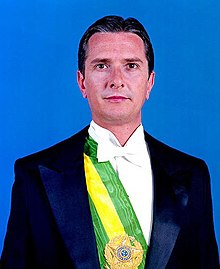

Presidency of Collor de Mello

| |

| Presidency of Collor de Mello 15 March 1990 – 29 December 1992 | |

Vice President | |

|---|---|

| Party | PRN |

| Election | 1989 |

| Seat | Alvorada Palace |

|

| |

The Collor government, also referred to as the Collor Era, was a period in Brazilian political history that began with the inauguration of President Fernando Collor de Mello on March 15, 1990, and ended with his resignation from the presidency on December 29, 1992. Fernando Collor was the first president elected by the people since 1960, when Jânio Quadros won the last direct election for president before the beginning of the Military Dictatorship.[1] His removal from office on October 2, 1992, was a consequence of his impeachment proceedings the day before,[2][3] followed by cassation.[4]

At the time, the national media also referred to the government by República das Alagoas (English: Republic of Alagoas). "It was synonymous for trouble. Journalists love labels, and that one seemed perfect," Ricardo Motta recalls.[5]

The Collor administration registered a 2.06% retraction in GDP and a 6.97% retraction in per capita income.[6]

Among the main laws sanctioned, the following can be cited: Consumer Defense Code (1990), Statute of the Child and Adolescent (1990), Law of the Legal Regime of Public Service Employees (1990), SUS Law (1990), Rouanet Law (1991), Law of Administrative Improbity (1992).[7][8]

Presidency

[edit]Economy

[edit]Collor Plan

[edit]The year before his administration began, official inflation measured by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics reached the unbelievable amount of 1,972.91%[9] and, for this reason, President Collor elected as his priority the fight against spiraling inflation through the so-called Plano Brasil Novo (English: New Brazil Plan), popularly known as the Plano Collor (English: Collor Plan). The plan was the fourth attempt undertaken by the federal government to combat hyperinflation, three of which were undertaken during the Sarney Government.[10] The country's economic situation was so perilous that the discussion did not revolve around the adoption of economic measures, but when and how these measures would be implemented. On the eve of his inauguration, Fernando Collor asked the Sarney government to declare a bank holiday, which only increased speculation about the measures that would be announced.[11]

The day after his inauguration, Collor presented his economic plan: he announced the return of the cruzeiro as the monetary unit to replace the cruzado novo, which had been in effect since January 15, 1989, when the last economic crisis sponsored by his predecessor took place.[10] The cruzeiro would return to circulation on March 19, 1990, in its third and last incursion as national currency, since it would be replaced by the cruzeiro real in 1993. In addition, Collor's measures for the economy also included impact actions such as: reduction of the administrative system with the extinction or merger of ministries and public agencies, dismissal of public employees, and the freezing of prices and salaries.[12]

During his administration, the country opened up to the external market, and efforts were made to eliminate or reduce anti-import barriers, adopting economic liberalization measures in favor of Brazil's insertion in the globalization scenario.[13][14] At the beginning of the government, the Industrial and Foreign Trade Policy (PICE) was launched, with the objective of increasing competitiveness and reducing the national industry's delay, acting internally with privatizations and externally with tax and foreign trade reform.[15] In a trip to Switzerland in 1990, Collor said that "Brazilian cars are carts". Besides the automobile market, the computer market was also leveraged by the opening of trade.[16] Another sector impacted was the cultural one, as it became more accessible and less expensive to release records.[17]

Confiscation of savings

[edit]One of the important points of the plan included the confiscation of bank deposits exceeding Cr$50,000.00 (fifty thousand cruzeiros) for a period of eighteen months, aiming to reduce the amount of money in circulation, as well as changes in the calculation of monetary correction and in the operation of financial investments. Even though bank confiscation was a flagrant disrespect to the constitutional right to property, the economic plan led by Minister of Economy Zélia Cardoso de Mello was approved by the National Congress in a matter of days.[18][19]

According to an article[20] by the academic Carlos Eduardo Carvalho, Professor of the Department of Economics at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and coordinator of the Government Program of the PT's candidacy for the Presidency of the Republic in 1989, the policy measure executed by the Collor government, which became known as confiscation, was not originally part of the Collor Plan and was conceived almost on the eve of its implementation. The confiscation was already a topic in debate among the candidates for the presidential election: "The genesis of the Collor Plan, in other words, how and when the program itself was formatted, was developed in Collor's advisory office from the end of December 1989, after his victory in the second round. The final version was probably greatly influenced by a document (written by Luiz G. Belluzzo and Júlio S. Almeida) discussed in the advisory office of the PMDB candidate, Ulysses Guimarães, and later in the advisory office of the PT candidate, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, between the first and second rounds of voting. Despite the differences in general economic strategies, the candidacies that faced each other amidst the sharp acceleration of price hikes, exposed to the risks of open hyperinflation in the second half of 1989, had no stabilization policies of their own. The proposal for a blockade originated in the academic debate and was imposed on the main presidential candidacies [...] When it became clear that the Ulysses campaign was running out of steam, the proposal was taken to the candidacy of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, of the PT, where it received great support from his economic advisors, and reached Zélia's team after the second round on December 17".[20]

Political articulation

[edit]

The new president Fernando Collor, originally from a state with little political influence and affiliated to a party with little political tradition, felt the need to build a base of support capable of allowing the implementation of his government's program, even though Collor himself was not inclined to connive with parliamentarians in their political contacts in order to approve projects of his interest.[21] This aversion caused a gap between the head of the executive and most of the congressmen who supported him, but, as a rule, his government was supported by politicians from the PFL, PDS, PTB, PL, smaller conservative parties and occasional dissidents.[22]

In the 1989 elections, his allies won in the Federal District and in most of the states, especially the PFL, which elected nine governors, six of them in the Northeast Region. This performance compensated for the defeats suffered in large electoral centers such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Rio Grande do Sul, for example. The curious thing is that, although Fernando Collor's party, the National Reconstruction Party (PRN), elected two senators and forty federal deputies, it did not elect a single governor. In the legislative branch, the PMDB maintained the largest number of seats in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate, and as a result, kept the command of congress for the next two years, a situation that had been in place since the return of the civilians to power in 1985. Throughout 1991, he invested most of his political capital in a negotiation to bring the Brazilian Social Democracy Party into the ranks of the situationist lines, a negotiation that failed, especially after the refusal of Mário Covas and Franco Montoro, the national president of the PSDB at the time.[22]

As for his team, changes would occur within two weeks of his inauguration, when Joaquim Roriz left the Ministry of Agriculture,[23] and in October 1990, when Bernardo Cabral was replaced in the Ministry of Justice and Public Security by the experienced senator Jarbas Passarinho. However, the most significant change would come in May 1991, when Ambassador Marcílio Marques Moreira took over the Ministry of Economy,[24] confirming Collor's appreciation for individuals with a technical and academic profile to the detriment of "career politicians", a trend that would only be reversed in 1992 when he carried out two reforms in his team: one in April and another on the eve of his removal when he made room for conservative political officials. When Collor took office, the number of ministers nominated by him was the lowest in the thirty years prior to 1990, and among those who were awarded a top-level position was former soccer player Artur Antunes Coimbra, also known as Zico, who would leave the post after a year.[25] Over time, the failure of his economic policy and the frequent accusations involving his direct aides (including first lady Rosane Malta, president of the Brazilian Legion of Assistance) resulted in a progressive wearing down of his government.[26][27]

Education

[edit]In 1991, the Integrated Centers for Child Care (CIACs) were established, part of the Minha Gente Project, inspired by the Integrated Centers for Public Education (CIEPs), created during Leonel Brizola's administration as governor of Rio de Janeiro. In 1992, they were renamed Comprehensive Care Centers for Children and Adolescents (CAICs).[28]

Health

[edit]CIACs were active in vaccination services, and community health agent posts and educational campaigns were expanded. According to Liz Batista, for Estadão (2021): "The campaigns that immunized against polio, measles, pertussis, diphtheria and tetanus, counted on the active participation of President Fernando Collor de Mello. Presidential trips and public events - mainly in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil - began to include vaccination acts". In a meeting of Ibero-American countries, the president offered help for immunization campaigns to more than 21 countries. Health Minister Alceni Guerra was awarded by UNICEF for the CIACs, a project that became a reference for other countries in their efforts to vaccinate children.[29]

International Policy

[edit]On March 26, 1991, Collor signed the Treaty of Asunción, the document that established the Mercosur.[30]

Indigenist Policy

[edit]He signed a decree on May 25, 1992,[31] which ratified the demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory (9.4 million ha).[32] The demarcation had been published in a decree signed by his Minister of Justice, Jarbas Passarinho, in 1991.[33] That same year, Collor also authorized the demarcation of the Menkragnoti Indigenous Territory (4.9 million ha).[34][35]

Social Security

[edit]He sanctioned Law 8,123, of 1991, which provides for the Social Security Benefit Plans, determining, among other provisions, the "uniformity and equivalence of benefits and services to urban and rural populations".[36] Rural pensioners now receive a minimum wage as a basic benefit instead of the half wage that was in effect until then. The regulation of the benefits was made by Decree no. 611, of July 21, 1992, which was revoked and replaced in 1997.[37] Decree no. 99,350, of June 27, 1990, merged the Institute of Financial Administration of Social Security and Social Assistance (IAPAS) with the National Institute of Social Security (INPS), creating the federal autarchy National Social Security Institute (INSS).[38]

Environment

[edit]He commanded the work of the Earth Summit at Rio-92, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development.[39] Due to the event, he transferred the federal capital to Rio de Janeiro from July 3 to 14, 1992, and called on the Armed Forces to provide security.[40] According to Celso Lafer (2012), who was his foreign minister: "President Collor's political will in this field is also very representative of his commitment to reformulate Brazil's domestic and international agenda in the post-Cold War world, which is an identifying mark of his government".[41] By decree of April 25, 1990, he created the Interministerial Commission for the Preparation of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Cima).[42]

Impeachment

[edit]

In mid-1991, accusations of irregularities began to appear in the press, involving people in Fernando Collor's close circle, such as ministers, friends of the president, and even the first lady Rosane Collor.[43] In an interview for Veja magazine in May 1992, Pedro Collor de Mello, the president's brother, exposed the corruption scheme that involved the former campaign treasurer Paulo César Farias, among other compromising facts for the president.[27] In the midst of the strong popular commotion, a Parliamentary Inquiry Commission was installed to investigate the president's responsibility over the publicized facts. On October 2, the impeachment process was opened in the Chamber of Deputies, driven by the massive presence of the people in the streets, such as the Caras-pintadas movement.[44]

On September 29, by 441 to 38 votes, the Chamber of Deputies authorizes the opening of impeachment proceedings against the president, which implies his temporary removal from office until a final decision is made by the Federal Senate. Collor resigns before being convicted. The presidency is assumed by then vice-president Itamar Franco.[45][46][47]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ "Primeiro presidente eleito após regime militar, Collor adota plano para matar inflação 'com um só tiro'". Agência Senado. 2010-03-24. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ "Impeachment de Collor faz 20 anos; relembre fatos que levaram à queda". 2012-09-28.

- ^ "Biblioteca da Presidência da República - Fernando Collor". Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ^ "Relembre o impeachment do presidente Fernando Collor, o 'caçador de marajás'". 2013-07-28.

- ^ Motta, Ricardo (2012-09-29). "Há 20 anos ruiu a República das Alagoas". Archived from the original on 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ "GDP growth (annual %) - Brazil". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- ^ "Collor ressalta importância de leis que sancionou como presidente da República". Agência Senado. 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ "Implantado por Collor, SUS faz 32 anos com mais de 91 bi de atendimentos". 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Carvalho, Sandra (2022-09-13). "Perdas econômicas, ganhos democráticos". Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ a b Moraes, Roberto Campos de (1989). "O Plano Verão: Prelúdio ao Plano Inverno (Outono?)". Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ "Há 30 anos, brasileiro recebia o anúncio de confisco da poupança". 2020-03-15. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ Welch, John; Birch, Melissa; Smith, Russell. "Economics: Brazil". Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Plano Collor, abertura de mercados e impeachment marcaram primeiro governo eleito após o Regime Militar". Agência Senado. 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Hidalgo, Maria Theresa Campos (2006). "A abertura comercial do Brasil nos anos 90 e sua relação com a terceirização de atividades". Federal University of Paraná. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Moreti, Fernando Piloto (2011). "Abertura comercial brasileira: contrapondo opiniões". São Paulo State University.

- ^ Mendonça, Jacy de Souza (2020-08-29). "Collor tinha razão; o carro brasileiro era uma carroça". Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Schott, Ricardo (2016-10-31). "Raimundos: A corrida do ouro". Super Interessante.

- ^ "A perplexidade do brasileiro diante do confisco das contas bancárias e poupanças (05' 44")". 2006-07-23. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Entre infartos, falências e suicídios: os 30 anos do confisco da poupança". Uol. 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ a b Carvalho, Carlos Eduardo (2006-04-01). "As origens e a gênese do Plano Collor". Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- ^ "Impeachment de Collor completa 15 anos". G1. 2007-12-29. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ a b "COLLOR, Fernando". Atlas Histórico do Brasil. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Joaquim Domingos Roriz". 2016-12-07. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Ministros de Estado da Fazenda - República". Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ Lima, Marcos Paulo (2023-03-03). "A vida discreta de Zico em Brasília quando foi ministro do Esporte". Correio Braziliense. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Mendes, Priscilla (2013-05-06). "Relembre casos do governo Collor que envolveram PC Farias". G1. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ a b Bertoni, Estevão; Varella, Juca (2018-07-13). "O crime que abalou o país". Uol. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "CIACs (Centros Integrados de Atendimento à Criança)". EducaBrasil. 2011. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Batista, Liz (2021-04-29). "Presidentes e vacinas: saiba como governantes atuaram em campanhas de imunização no Brasil". Estadão. Retrieved 2023-03-03.

- ^ Westin, Ricardo (2021-03-05). "Criação do Mercosul pôs fim às tensões históricas entre Brasil e Argentina". Agência Senado. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Em meio à crise, ex-presidente relembra demarcação da TI Yanomami". Folha de Boa Vista. 2023-01-23. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Decreto de 25 de maio de 1992". Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ Passarinho, Jarbas (1991). "Portaria nº 580 de 15 de novembro de 1991".

- ^ "Collor demarca área indígena com 4,9 milhões de hectares". Jornal do Brasil. 1991-11-29. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Índios ganham mais 4,9 milhões de hectares". Correio Braziliense. 1991-11-28. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Lei nº 8.213 de 24 de julho de 1991".

- ^ "Decreto nº 611 de 21 de julho de 1992".

- ^ "Decreto nº 99.350 de 27 de junho de 1990".

- ^ Cardim, George (2011-06-15). "Collor é homenageado na celebração dos 20 anos da Rio-92". Rádio Senado. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ "Rio-92: mundo desperta para o meio ambiente". 2009-12-10. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ Lafer, Celso (2012-04-04). "O significado da Rio-92 e os desafios da Rio+20" (PDF).

- ^ "Decreto nº 99.221 de 25 de abril de 1990".

- ^ Rodrigues, Natália. "Governo de Fernando Collor". InfoEscola. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "Relembre o impeachment e o governo Collor". Folha de São Paulo. 2010-10-02. Retrieved 2023-04-19.

- ^ Ziegler, Maria Fernanda (2007-12-01). "O impeachment de Collor". Archived from the original on 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ "20 ANOS DO IMPEACHMENT DO COLLOR". Retrieved 2023-01-31.

- ^ "Arquivo Gaúcha relembra cobertura do impeachment de Fernando Collor". 2016-07-02. Retrieved 2023-01-31.

Additional Reading

[edit]- Antonio Villa, Marco (2016-06-13). Collor presidente: trinta meses de turbulências, reformas, intrigas e corrupção. Record. ISBN 9788501090539.