Potrero Hill

Potrero Hill | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 37°45′26″N 122°23′59″W / 37.75716°N 122.39986°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Named for | potrero nuevo (new pasture) |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Shamann Walton |

| • Assemblymember | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. rep. | Nancy Pelosi (D)[2] |

| Area | |

• Total | 1.52 sq mi (3.9 km2) |

| Population | |

• Total | 14,102 |

| • Density | 9,300/sq mi (3,600/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 94107, 94110, 94124 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

Potrero Hill is a residential neighborhood in San Francisco, California. A working-class neighborhood until gentrification in the late 1990s, it is now home to mostly upper-income residents.[4]

Location

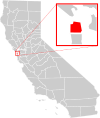

[edit]Potrero Hill is located on the eastern side of the city, east of the Mission District and south of SOMA (South of Market) and the newly[when?] designated district Showplace Square.[5] It is bordered by 16th Street to the north, Potrero Avenue and U.S. Route 101 (below 20th Street) to the west and Cesar Chavez Street to the south. The city of San Francisco considers the area below 20th Street between Potrero Ave and Route 101 to be part of Potrero Hill as well, as outlined in the Eastern Neighborhood Plan.[6]

The area east of Highway 280 between Mariposa and Cesar Chavez (and west of the waterfront) is known as Dogpatch. Dogpatch was originally part of Potrero Nuevo and its history is closely tied to Potrero Hill. Some consider Dogpatch to be its own neighborhood while others disagree, although the City has Dogpatch in its neighborhood plans.[7] Dogpatch has its own neighborhood association but shares merchant association, Democratic caucuses, and general neighborhood matters with Potrero Hill.

Characteristics

[edit]According to Google Earth, the highest point in the neighborhood is 104 meters (about 341 feet) above sea level, at the site of a water tower that was demolished in 2006.

Potrero Hill started as a Caucasian working-class neighborhood in the 1850s. Its central location attracted many working professionals during the dot-com era in the 1990s. Today, it is mostly an upper-middle-class family-oriented neighborhood.[citation needed] In addition to the 101 and 280 Interstate freeways, Caltrain also runs through this area.

History

[edit]Industry first arrived at Dogpatch in the mid-1850s. The earliest residents were mostly European immigrants. Over time, Dogpatch became more industrialized and many residents moved up the hill to Potrero Hill, turning it into a residential neighborhood. It remained blue-collared and working-class until the mid-1990s when gentrification turned it into a mostly working professional neighborhood, zoned by the San Francisco Planning Department to include light industry and small businesses.[8]

Early history

[edit]Potrero Hill was uninhabited land for much of its history, used sporadically by Native Americans as hunting ground. Its soil, developed on ultramafic, serpentine rock,[9] promoted not a closed forest but an open landscape of shrub and grass. In the late 1700s, Spanish missionaries grazed cattle on the hill and named this area Potrero Nuevo,[citation needed] "Potrero" is Spanish for "pasture": "Potrero Nuevo" means "new pasture".

Potrero Nuevo granted to the De Haro family

[edit]Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. In 1844, the Mexican government granted Potrero Nuevo to Francisco and Ramon de Haro, the 17-year-old twin sons of Don Francisco de Haro, then mayor of Yerba Buena. Just two years later, Francisco and Ramon de Haro, along with their uncle Jose de los Reyes Berreyesa, were killed during the Bear Flag Revolt in San Rafael at the order of U.S. Army Major John C. Fremont, who had declared war on Mexico. With the death of his sons, Don Francisco de Haro became owner of Potrero Nuevo.[10][11]

Construction of street grids in the Gold Rush Era

[edit]In 1848, after the conclusion of the Mexican–American War, Mexico ceded all of California, and it was admitted into the Union in 1850. Dr. John Townsend became the second mayor of the town now called San Francisco (changed from Yerba Buena in 1847). He succeeded de Haro, who was distraught over the death of his twin sons.

With the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848, San Francisco experienced unprecedented rapid growth. Townsend envisioned developing Potrero Hill as a community for migrants and their newfound riches. Townsend, a good friend of de Haro, approached him about dividing his land into individual lots and selling them.[citation needed] De Haro, with his land rights already challenged and fearing that the United States government would now strip him of Potrero Nuevo, agreed to Townsend's suggestion. Together with surveyor Jasper O'Farrell, recent emigrant Cornelius De Boom, and Captain John Sutter, they hashed out the grid and street names. Townsend named the north-south streets after American states (Arkansas, Utah, Kansas, etc.) and the east-west streets after California counties (Mariposa, Alameda, Butte, Santa Clara, etc.). At this time, Potrero Hill was not part of San Francisco, so the men marketed this area as "South San Francisco".[citation needed]

Historians speculate that "merging the United States with the counties of California would attract homesick easterners" and their newly acquired gold-rush riches to settle in the neighborhood.[11] There is also speculation that Townsend named the north-south streets after states which he had been to, with Pennsylvania Street (his home state) being an extra wide street. However, there is no record of Townsend ever having been to Texas or Florida, whose names appear as streets. Another theory is that battleships named after the states were the source of the street names.[12] The east-west county street names survived until 1895, but as the city expanded, the Post Office demanded a simplification of the street grids. Most of the county streets took the names of the numbered streets that connected them to downtown, but because they didn't all line up exactly, a few county streets survived (such as Mariposa and Alameda).[11]

By the standard of the mid-nineteenth century, Potrero Hill was not a convenient location to get to—it was still separated by Mission Bay, which was not yet filled in. Prospective buyers partly deemed Potrero Hill too far away and were wary of De Haro's uncertainty as legal owner of the land.[citation needed] As a result, only a few lots were sold. In late 1849, Don Francisco de Haro died, and he was buried in Mission Dolores.

Industry and squatters

[edit]After the death of de Haro, squatters began to overtake Potrero Hill around Potrero Point. The de Haro family tried to maintain control of the land but the family's ownership became a legal matter. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court when in 1866 it ruled against the de Haro family. Residents of Potrero Hill celebrated with bonfires after learning of the outcome, some of whom gained title to the lot where they squatted through the Squatter's Rights.

Development eventually came in the early 1850s, not in the form of rich gold-miners envisioned by Townsend, but in a more blue-collar variety. The forerunner of PG&E opened a plant in the eastern shores of Potrero Hill (modern day Dogpatch) in 1852. Not long after, a gunpowder factory (gunpowder was vital for gold mining) opened nearby; then shipyards, iron factories, and warehouses followed. In 1856, San Francisco Cordage (agents: Tubbs & Co.) opened its extensive manufactory of Manila rope.[13] Potrero Point experienced a minor boom in housing as factory workers preferred to live nearby. The opening of the Long Bridge in the 1860s would drastically change the dynamics of Potrero Hill.

The Long Bridge opened up Potrero

[edit]In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Pacific Railway Act that provided Federal government support for the building of the first transcontinental railroad. In anticipation of the railroad, San Francisco built the Long Bridge in 1865 that connected San Francisco proper (foot of Third St.) over Mission Bay to Potrero Hill and Bayview. Potrero Hill, once deemed too far south, was suddenly a mile-long promenade away. The Long Bridge completely transformed Potrero Nuevo from no man's land to a central hub. One of the first of many waves of real estate speculation on Potrero Hill soon followed. The Long Bridge was closed after Mission Bay was filled in the early 1900s, which made Potrero Hill an even more desirable location.[citation needed]

European migration

[edit]

Potrero Hill was spared from the earthquake that struck San Francisco in 1906. Displaced San Franciscans set up tents and shelter on the hill. Many residents moved to the hill after their dwellings were devastated by fire, including a large population of Russian and Slovenian immigrants who previously resided in South of Market. The influx of new residents to Potrero Hill diversified the neighborhood's demographic.

In August 1906 a group of Spiritual Christians from Russia (Molokans and a few Pryguny) arrived from Hawaii, where they refused to farm sugar cane, but some got work with the steamship lines and were transferred to San Francisco. More Molokans arrived from Los Angeles, Russia and Manchuria. By 1928 they built a 2-story meeting hall on Carolina street, and soon organized the Russian Sectarian Cemetery in Colma with Spiritual Christian Baptists, Evangelicals and Adventists from Russia.[citation needed]

By the early 1900s, a large concentration of European immigrants had settled. The new immigrants, now displaced by the earthquake and fire, had the burden of starting a new home and the strains of entering a new culture. Rev. William E. Parker, Jr., pastor of Olivet Presbyterian Church at 19th and Missouri Street took action by opening his home and began offering English classes.[14] Initially the classes were held for men and later offered for women and youth. In 1918, the growing needs of the neighborhood warranted the incorporation of the Neighborhood House under the California Synodical Society of Home Missions, an organization of Presbyterian Church women. In 1919, renowned architect Julia Morgan was commissioned to design a permanent neighborhood house, now at 953 De Haro Street. On June 11, 1922, the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House, fondly nick-named "the NABE", was completed.[15][16]

The two earliest residential neighborhoods were the Irish Hill and Dutchman's Flat (both located in modern-day Dogpatch). The infamous Irish Hill, located east of Illinois St and right next to the factories, housed mainly Irish factory workers in boarding houses. Irish gangs were formed and crimes were rampant.[citation needed] Irish Hill was leveled for use as landfill and the residents displaced in 1918.

Over half of Potrero Hill's population at this time was Irish immigrants; Scots, Swiss, Russians, Slovenians, Serbians and Italians made up most of the remaining population. Native born whites made up less than 20% of the population.[citation needed] Today, the remnant of these ethnic groups' heritage is still visible, such as Slovenian Hall on Mariposa St. and the First Russian Christian Molokan Church on Carolina St.

Potrero Hill settlement and Dogpatch industrialization

[edit]As Dogpatch became more industrialized, with warehouses and factories expanded west of Illinois St, many Dogpatch residents moved west up onto Potrero Hill. The divide between the industrial Dogpatch and the residential Potrero Hill would grow over time, each neighborhood developing its own distinct feel.[citation needed]

Freeways and southern development

[edit]Originally, four public housing projects were constructed during and after World War II. Two housing projects have since been removed to make way for the Starr King Elementary School and townhouses.

The United States' decision to enter WWII created an industrial boom in Dogpatch, led by the shipyards that constructed Navy ships. Potrero Hill's South Slope experienced a significant increase in housing and population as a result.

In the 1950s the James Lick Freeway (US Route 101) that slices through the neighborhood was constructed amid much controversy. To obtain the necessary land for the freeways, some residents were forced to vacate their homes in exchange for significantly below-market prices paid by the government. In the 1960s, another freeway (Interstate 280) was constructed along Potrero Hill's East side amid similar controversies.

Hotbed for artists and LGBT

[edit]In the 1960s many artists and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community began to move to Potrero Hill, drawn by its location and affordable rent. Many artist studios, showrooms and art schools were set up nearby in response to Potrero Hill's explosion as a creative hub. The city has since designated the collection of designer warehouses, art schools, and showrooms just north of Potrero Hill as a special light-industrial district and named this area the Showplace Square.[5]

Dot-com and gentrification

[edit]

With its close proximity to offices in SOMA, Financial District, and Multimedia Gulch (Mission District bordered by 16th St, Potrero Ave, Folsom St, and 20th St.), and the burgeoning night life and dining in the Mission District, SOMA, and its own 18th St. corridor, Potrero Hill, along with its neighboring Mission District, drew many high-tech professionals in the dot-com era, driving up real estate prices and rent. Up until 2015, it was home to the American headquarters for major game publisher SEGA. The neighborhood saw a drastic change from mostly working-class to mostly white-collared professionals.[citation needed]

Modern era

[edit]The neighborhood is[when?] still in the midst of change and transformation with the implementation of the city's Eastern Neighborhood Plan,[17] the redevelopment of Potrero Annex and Potrero Terrace housing projects, and its neighboring Mission Bay's development into a bio-technology hub. Redevelopment of the southern edge of Potrero Hill began in 2020.[18]

Demographics

[edit]According to the 2005 to 2010 census data gathered by the San Francisco Planning Dept.[19]

| Total Population | 12,110 |

| Male | 52% |

| Female | 43% |

| Median Household Income | $98,182 |

| Median Family Income | $110,657 |

| Per Capita Income | $58,650 |

| White | 66% |

| Asian | 13% |

| Latino (of any race) | 13% |

| Other | 10% |

| African American | 9% |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1% |

| Total Households | 5,810 |

| Family Households | 43% |

| Households with Children, % of Total | 19% |

| Non-Family Households | 57% |

| Single Person Households, % of Total | 38% |

| Avg. Household Size | 2.3 |

| High School or Less | 17% |

| Some College/Associate Degree | 18% |

| College Degree | 36% |

| Graduate/Professional Degree | 28% |

Attractions

[edit]

The hub of Potrero Hill is the 18th Street corridor that features many trendy restaurants.

The stretch of Vermont Street between 20th Street and 22nd Street has many switchbacks, similar to the tourist attraction Lombard Street, known as "the most crooked street in the world." Vermont Street features a series of seven sharp turns, making it more crooked than better-known Lombard Street. (Vermont, while steeper than Lombard, has one fewer turn). Bottom of the Hill on 17th Street is a popular live music venue. Football star O. J. Simpson once lived in the public housing projects on the southeastern side of the hill. 18th Street runs through the heart of the north side of the hill and is home to three blocks that serve as the primary shopping and dining spot in the neighborhood.[20][21][22][23] The powder blue water tower, located near 22nd Street and Wisconsin Street, was demolished in mid-2006 (as part of a seismic upgrade and due to the fact that it was no longer needed). The main campus of the California Culinary Academy was located at 350 Rhode Island Street until 2017. The facilities included professional kitchens, student-staffed restaurants, lecture classrooms, a library, and a culinary laboratory. At the foot of Potrero Hill is the campus of the California College of the Arts and the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts.

The Anchor Brewing Company operated a brewery and distillery on Mariposa Street, between Carolina and De Haro Streets. It produced California Common beer, also known as Steam Beer, a trademark owned by the company. SEGA of America, the American publishing arm for one-time gaming giant SEGA, once operated out of an office on Rhode Island St.

The Potrero Hill Neighborhood House,[24] known as "the NABE", is located at the top of De Haro Street, at Southern Heights Avenue, and offers various community services. It was designed by architect Julia Morgan.

The headquarters for the Discovery Channel program MythBusters is located at the southern edge of the neighborhood.[citation needed]

Two freeways run through Potrero Hill, US Route 101 on the western side and Interstate 280 on the eastern side. Caltrain's 22nd Street station is on the eastern edge of the hill, and the San Francisco Municipal Railway (MUNI), provides bus service in the area (the 19-Polk, 22-Fillmore, 10-Townsend, and 48-Quintara - 24th St) and the new light rail service, completed in 2006, on 3rd Street (the T-Third Street).[25]

Living

[edit]Potrero Hill has deep working-class roots but over the last two decades[when?] has experienced rapid transition to a white-collar neighborhood. It is popular with families and working professionals, many with ties to the technology industry.[citation needed]

Architecture

[edit]Single-family homes comprise 33% of the housing stock, while 2–4 unit buildings comprise 34%.[citation needed]

Most of Potrero Hill's soil is serpentine, the best soil for ensuring a solid foundation. Thus,[original research?] this area managed to survive two major San Francisco earthquakes.{{ However, drilling through the serpentine rocks is time- and labor-intensive, so many houses were built by conforming to the slope of the hill. As a result, some houses on Potrero Hill have long staircases leading to the front entrances, often with detached garages at the street level. Houses on the elevated side of the hill usually are two to four stories high to maximize the view. Houses on the other side of the street from the elevated side usually look like single-story homes but typically have one or more levels underneath the street level.

Amenities

[edit]Mckinley Square is a park that sits atop Potrero Hill. Part of Vanessa Diffenbaugh's book The Language of Flowers[26] describes the park. The park contains several levels of trails that make up the official off-leash dog area. Its adjacent Potrero Hill Community Garden[27] was established in the 1970s, operating under the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and boasts panoramic view of the city. Potrero Hill Recreation Center was renovated in 2011 and has a baseball field, a tennis court, a basketball court, and a dog park. Likewise, the Jackson Playground at the North Slope also has a baseball field, a tennis court, and a basketball court. Both Rec & Park facilities have a children's playground. The public library[28] was renovated in 2010 and is located on 20th St. and Connecticut St.

Education

[edit]The two San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) elementary schools serving Potrero Hill are Starr King Elementary School and Daniel Webster Elementary School.[29] Starr King offers the only public Mandarin immersion elementary school program on the city's east side. Webster opened in 1936 and has a bilingual Spanish program.[30] SF International High School is also located in Potrero Hill.

Movies and arts

[edit]Potrero Hill was the fictional home neighborhood of Inspector Harry Callahan in the Dirty Harry movie series.

Parts of the famous car chase scene featuring Steve McQueen in the classic 1968 action film Bullitt were shot in the Potrero Hill neighborhood (Kansas Street and 20th Street and, seconds later, at Rhode Island Street and 20th Street).

The 1990 movie Pacific Heights was shot on location at Potrero Hill, not at the location of the movie's title.

In the 1993 film The Joy Luck Club (film), the character Rose Hsu Jordan lives with her husband at Rhode Island Street and 18th Street, in a modern house once owned by real-life musician Joan Jeanrenaud of the Kronos Quartet. The Jordan character fought for the house in a divorce settlement.

In the 2001 film Sweet November, the character Sara Deever (played by Charlize Theron) lives at 18th Street and Missouri Street.

The 2011 film Contagion features a scene shot on a steep block of De Haro Street between 20th Street and Southern Heights Avenue with a great view of downtown in the background.

In the 1981 film Chu Chu and the Philly Flash, Chu Chu (played by Carol Burnett) lives in a place on Southern Heights Avenue that has since been demolished and reconstructed as an apartment building.

In author James Patterson's bestselling Women's Murder Club book series, protagonist Lt. Lindsay Boxer, a San Francisco policewoman, lives in a walk-up on Potrero Hill, from which she can see Oakland and the Bay.

In the 1970s TV series The Streets of San Francisco, Lt. Mike Stone (played by Karl Malden) lives in a house on De Haro Street. Potrero Hill is also featured in the television series Nash Bridges and Party of Five.

The 2002 film 40 days and 40 nights was filmed in this area.

Notable residents

[edit]- Art Agnos, former mayor of San Francisco

- John L. Burton, John Lowell Burton is the Chairman of the California Democratic Party since April 2009; he is an American politician who served as a Democratic California State Senator from 1996 until 2004, representing the 3rd District.

- Robert Bechtle, photorealist painter, used the hill for both a home and subject matter for his art.

- Wayne M. Collins (1899–1974), civil rights attorney who grew up in the Potrero Hill neighborhood.

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti, poet and co-founder of City Lights, America's first all-paperback bookstore; Ferlinghetti bought the house at 706 Wisconsin St. in 1957.

- Danny Glover, movie actor, lived in the Potrero Hill housing projects as a youth.

- Frank Herbert, science fiction author, lived at 412 Mississippi Street, San Francisco, where he wrote Dune, published 1965.[31]

- Joan Jeanrenaud, cello player and member of the Kronos Quartet.

- Gene Merlino, Grammy Award winning singer and musician, was born near Kansas and 19th Streets and lived there for 25 years.

- Miguel Migs, deep house producer and deejay; founder of Salted Music: a house music record label (originally spun off from another San Francisco-based label; Om Records)

- Peter Orlovsky, poet Allen Ginsberg's partner, lived at 5 Turner Terrace, one of several federal post-WWII Potrero Hill housing projects, in the 1950s.

- Terry Riley composed the piece "In C" "in a tiny house at the top of Potrero Hill"[32] in 1964. This work had a profound effect on music composition.

- O. J. Simpson, American athlete and actor, lived in the Potrero Hill housing projects as a youth.

- Kevin Starr, historian and author, winner of National Humanities Medal and inductee to California Hall of Fame, also grew up in the Potrero Hill housing projects as a youth.

- Blanche Thebom, American mezzo-soprano who sang with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City for almost 20 years[33]

- Wayne Thiebaud, painter, lived on and painted Potrero Hill for years.

- Erling Wold, composer and Associate Music Director of the San Francisco Composers Chamber Orchestra

- Jacob Weisman, World Fantasy Award–winning publisher of Tachyon Publications

Public housing projects

[edit]Two public housing projects—the Potrero Terrace and Potrero Annex—are located in the South Slope. An estimated 1,200 people live[when?] in the Terrace and Annex with 555 of the 606 units occupied. The non-profit organization Hope SF, partnering with a private developer, is planning[when?] to demolish the projects and build mixed-income housing under the plan Rebuild Potrero.[34]

See also

[edit]- Dogpatch, San Francisco, California

- Irish Hill (San Francisco)

- List of San Francisco, California Hills

- Mission Bay, San Francisco, California

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "California's 11th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b "Potrero Hill neighborhood in San Francisco, California (CA), 94107, 94124 subdivision profile". City-Data.com. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Carpenter, Les (2016-02-03). "How the poor neighborhood that OJ forgot turned rich and forgot him back". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ a b "Showplace Square Open Space Plan - Planning Department". www.sf-planning.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- ^ "Eastern Neighborhood Plan". Archived from the original on 2013-08-29. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- ^ "Central Waterfront/Dogpatch Public Realm Plan". sfplanning.org. San Francisco Board of Supervisors. October 2018.

- ^ The Potrero View, June, 2008 https://web.archive.org/web/20080701184050/http://www.potreroview.net/news10034.html

- ^ "Serpentine Grasslands and Maritime Chaparral - FoundSF". foundsf.org.

- ^ Solnit, Rebecca (2006-06-25). "Of illegal immigration and bloodshed -- in 1846 / Celebrated killings highlight dubious path to statehood". Sfgate.

- ^ a b c "The Potrero View : Serving the Potrero Hill, Dogpatch, Mission Bay & SOMA neighborhoods of San Francisco since 1970". Archived from the original on 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ^ "San Francisco Days: An Exploration of San Francisco Neighborhoods". www.sanfranciscodays.com.

- ^ "The San Francisco Cordage and Oakum Manufactory". cdnc.ucr.edu. Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 12, Number 1811. 16 January 1857.

- ^ Carlsson, Chris. "Neighborhood House". FoundSF. Retrieved 2023-05-23.

- ^ Linenthal, Peter; Johnston, Abigail (2005-07-27). San Francisco's Potrero Hill. Potrero Hill Archives Project. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 73–75. ISBN 978-1-4396-3082-2.

- ^ Linenthal, Peter; Johnston, Abigail (2009-04-01). Potrero Hill. Arcadia Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7385-5966-7.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "REBUILDPotrero". Mysite. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-07-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ SFGate San Francisco Neighborhood Guide; last accessed 16 February 2008.

- ^ SF Weekly Restaurant Guide; last accessed 16 February 2008. Archived January 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 7X7, "Bringing Up Baby" Archived 2007-10-19 at archive.today; last accessed 16 February 2008.

- ^ SF Station, "A Magnificent Potrero Hill Trio" Archived 2008-02-12 at the Wayback Machine; last accessed 16 February 2008.

- ^ "nabe". nabe.

- ^ "Route Guide for All Muni Lines". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ^ Diffenbaugh, Vanessa (3 April 2012). The Language of Flowers: A Novel. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345525550 – via Amazon.

- ^ "Potrero Hill Community Garden". www.potrerogarden.org.

- ^ "Potrero". SFPL.

- ^ "Final Recommendations for Elementary Attendance Areas Prepared for September 28, 2010 Board Meeting." San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved on April 18, 2018.

- ^ "Daniel Webster Elementary School." San Francisco Unified School District. Retrieved on April 18, 2018.

- ^ The Potrero View, September 2021

- ^ Ramon Sender In C 25th Anniversary Concert liner notes New Albion Records

- ^ Blanche Thebom: A True Diva Archived 2010-05-17 at the Wayback Machine The Potrero View, May 2010

- ^ Rebuild Potrero.

Further reading

[edit]- San Francisco's Potrero Hill by Peter Linenthal, Abigail Johnston, and the Potrero Hill Archives Project, Arcadia Publishing, 2005. Includes early Native American Ohlone history, Mission Dolores, early industry, both world wars, the 1960s, and recent developments.

External links

[edit]- SF Planning Commission - Eastern Neighborhoods Community Plans Archived 2011-06-16 at the Wayback Machine

- San Francisco Neighborhoods: Potrero Hill—Neighborhood guide from the San Francisco Chronicle

- Potrero Hill SF—Neighborhood guide and blog

- Potrero Boosters Neighborhood Association

- Showplace Square/Potrero Hill AREA PLAN