Prostitution in ancient Greece

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Prostitution was a common aspect of ancient Greece.[note 1] In the more important cities, and particularly the many ports, it employed a significant number of people and represented a notable part of economic activity. It was far from being clandestine; cities did not condemn brothels, but rather only instituted regulations on them.

In Athens, the legendary lawmaker Solon is credited with having created state brothels with regulated prices. Prostitution involved both sexes differently; women of all ages and young men were prostitutes, for a predominantly male clientele.

Simultaneously, extramarital relations with a free woman were severely dealt with. In the case of adultery, the cuckold had the legal right to kill the offender if caught in the act; the same went for rape. Female adulterers, and by extension prostitutes, were forbidden to marry or take part in public ceremonies.[1]

Pornai

[edit]The pornai (πόρναι)[note 2] were found at the bottom end of the scale. They were the property of pimps or pornoboskós (πορνοβοσκός) who received a portion of their earnings (the word comes from pernemi πέρνημι "to sell"). This owner could be a citizen, for this activity was considered as a source of income just like any other: one 4th-century BC orator cites two; Theophrastus in Characters (6:5) lists pimp next to cook, innkeeper, and tax collector as an ordinary profession, though disreputable.[2] The owner could also be a male or female metic.

In the classical era of ancient Greece, pornai were slaves of barbarian origin; starting in the Hellenistic era the case of young girls abandoned by their citizen fathers could be enslaved. They were considered to be slaves until proven otherwise. Pornai were usually employed in brothels located in "red-light" districts of the period, such as Piraeus (port of Athens) or Kerameikos in Athens.

The classical Athenian politician Solon is credited as being the first to institute legal public brothels. He did this as a public health measure, in order to contain adultery. The poet Philemon praised him for this measure in the following terms:

[Solon], seeing Athens full of young men, with both an instinctual compulsion, and a habit of straying in an inappropriate direction, bought women and established them in various places, equipped and common to all. The women stand naked that you not be deceived. Look at everything. Maybe you are not feeling well. You have some sort of pain. Why? The door is open. One obol. Hop in. There is no coyness, no idle talk, nor does she snatch herself away. But straight away, as you wish, in whatever way you wish.

You come out. Tell her to go to hell. She is a stranger to you.[3]

As Philemon highlights, the Solonian brothels provided a service accessible to all, regardless of income. (One obolus is one sixth of one drachma, the daily salary of a public servant at the end of the 5th century BC. By the middle of the 4th century BC, this salary was up to a drachma and a half.) In the same light, Solon used taxes he levied on brothels to build a temple to Aphrodite Pandemos (literally "Aphrodite of all the people").[4]

In regards to price, there are numerous allusions to the price of one obolus for a cheap prostitute; no doubt for basic acts. It is difficult to assess whether this was the actual price or a proverbial amount designating a "good deal".

Independent prostitutes who worked the street were on the next higher level. Besides directly displaying their charms to potential clients they had recourse to publicity; sandals with marked soles have been found which left an imprint that stated ΑΚΟΛΟΥΘΕΙ AKOLOUTHEI ("Follow me") on the ground.[5] They also used makeup, apparently quite outrageously. Eubulus, a comic author, offers these courtesans derision:

"plastered over with layers of white lead, … jowls smeared with mulberry juice. And if you go out on a summer's day, two rills of inky water flow from your eyes, and the sweat rolling from your cheeks upon your throat makes a vermilion furrow, while the hairs blown about on your faces look grey, they are so full of white lead".[6]

These prostitutes had various origins: Metic women who could not find other work, poor widows, and older pornai who had succeeded in buying back their freedom (often on credit). In Athens they had to be registered with the city and pay a tax. Some of them made a decent fortune plying their trade. In the 1st century, at Qift in Roman Egypt, passage for prostitutes cost 108 drachma, while other women paid 20.[7]

Their tariffs are difficult to evaluate: they varied significantly. The average charge for a prostitute in 5th and 4th century ranged from three obols to a drachma.[8] Expensive prostitutes could charge a stater (four drachmas),[9] or more, like the Corinthian Lais in her prime did.[10] In the 1st century BC, the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara, cited in the Palatine anthology, V 126, mentions a system of subscription of up to five drachma for a dozen visits. In the 2nd century, Lucian in his Dialogue of the Hetaera has the prostitute Ampelis consider five drachma per visit as a mediocre price (8, 3). In the same text a young virgin can demand a mina, that is 100 drachma (7,3), or even two minas if the customer is less than appetizing. A young and pretty prostitute could charge a higher price than her in-decline colleague; even if, as iconography on ceramics demonstrates, a specific market existed for older women. The price would change if the client demanded exclusivity. Intermediate arrangements also existed; a group of friends could purchase exclusivity, with each having part-time rights.

Musicians and dancers working at male banquets can also undoubtedly be placed in this category. Aristotle, in his Constitution of the Athenians (L, 2) mentions among the specific directions to the ten city controllers (five from within the city and five from the Piraeus), the ἀστυνόμοι astynomoi, that "it is they who supervise the flute-girls and harp-girls and lyre-girls to prevent their receiving fees of more than two drachmas"[11] per night. Sexual services were clearly part of the contract,[12] though the price, in spite of the efforts of the astynomi, tended to increase throughout the period.

Hetaera

[edit]More expensive and exclusive prostitutes were known as hetaerae, which means "companion". Hetaerae, unlike pornai, engaged in long-term relationships with individual clients, and provided companionship as well as sex.[13] Unlike pornai, hetaerae seem to have been paid for their company over a period of time, rather than for each individual sex act.[14] Hetaerae were often educated,[15] and free hetaerae were able to control their own finances.[16] Hetairai are described as providing "flattering and skillful conversation" in Athenaeus' Deipnosophistai. Classical literature describes hetairai as performing similar social functions as intellectual companions.[17]

Temple prostitution in Corinth

[edit]Around the year 2 BC, Strabo (VIII,6,20) in his geographic/historical description of the town of Corinth wrote some remarks concerning female temple servants in the temple of Aphrodite in Corinth, which perhaps should be dated somewhere in the period 700–400 BC:[18]

The temple of Aphrodite was so rich that it employed more than a thousand hetairas,[note 3] whom both men and women had given to the goddess. Many people visited the town on account of them, and thus these hetairas contributed to the riches of the town: for the ship captains frivolously spent their money there, hence the saying: 'The voyage to Corinth is not for every man'. (The story goes of a hetaira being reproached by a woman for not loving her job and not touching wool,[note 4] and answering her: 'However you may behold me, yet in this short time I have already taken down three pieces'.[note 5])

The text in more than one way hints at the sexual business of those women. Remarks elsewhere of Strabo (XII,3,36: "women earning money with their bodies") as well as Athenaeus (XIII,574: "in the lovely beds picking the fruits of the mildest bloom") concerning this temple describe this character even more graphically.

In 464 BC, a man named Xenophon, a citizen of Corinth who was an acclaimed runner and winner of pentathlon at the Olympic Games, dedicated one hundred young girls to the temple of the goddess as a sign of thanksgiving. We know this because of a hymn which Pindar was commissioned to write (fragment 122 Snell), celebrating "the very welcoming girls, servants of Peïtho and luxurious Corinth".[19]

The work of gender researchers like Daniel Arnaud,[20] Julia Assante[21] and Stephanie Budin[22] has cast the whole tradition of scholarship that defined the concept of sacred prostitution into doubt. Budin regards the concept of sacred prostitution as a myth, arguing taxatively that the practices described in the sources were misunderstandings of either non-remunerated ritual sex or non-sexual religious ceremonies, possibly even mere cultural slander.[23] Although popular in modern times, this view has not gone without being criticized in its methodological approach,[24] including accusations of an ideological agenda.[25]

Sparta

[edit]In archaic and classical Sparta, Plutarch claims that there were no prostitutes due to the lack of precious metals and money, and the strict moral regime introduced by Lycurgus.[26] A 6th century vase from Laconia, which shows a mixed-gender group at what appears to be a symposium,[27] might be interpreted as depicting a hetaira, contradicting Plutarch.[28] However, Sarah Pomeroy argues that the banquet depicted is religious, rather than secular, in nature, and that the woman depicted is not therefore a prostitute.[28]

As precious metals increasingly became available to Spartan citizens, it became easier to access prostitutes. In 397, a prostitute at the perioicic village of Aulon was accused of corrupting Spartan men who went there. By the Hellenistic period, there were reputedly sculptures in Sparta dedicated by a hetaera called Cottina.[26] A brothel named after Cottina also seems to have existed in Sparta, near to the temple of Dionysus by Taygetus, at least by the Hellenistic period.[29]

Social conditions

[edit]

The social conditions of prostitutes are difficult to evaluate; as women were already marginalized in Greek society. We know of no direct evidence of either their lives or the brothels in which they worked. It is likely that the Greek brothels were similar to those of Rome, described by numerous authors and preserved at Pompeii; dark, narrow, and malodorous places. One of the many slang terms for prostitutes was khamaitypếs (χαμαιτυπής) 'one who hits the ground', suggesting to some literal-minded commentators that their activities took place in the dirt or possibly on all fours from behind. Given the Ancient Greeks' propensity for poetic thinking, it seems just as likely that this term also suggested that there is 'nothing lower', rather than that a significant proportion of prostitutes were reduced to plying their trade in the mud.[citation needed]

Certain authors have prostitutes talking about themselves: Lucian in his Dialogue of courtesans or Alciphron in his collection of letters; but these are works of fiction. The prostitutes of concern here are either independent or hetaera: the sources here do not concern themselves with the situation of slave-prostitutes, except to consider them as a source of profit. It is quite clear what ancient Greek men thought of prostitutes: primarily, they are reproached for the commercial nature of the activity. The acquisitiveness of prostitutes is a running theme in Greek comedy. The fact that prostitutes were the only Athenian women who handled money may have increased acrimony towards them. An explanation for their behavior is that a prostitute's career tended to be short, and their income decreased with the passage of time: a young and pretty prostitute, across all levels of the trade, could potentially earn more money than her older, less attractive colleagues. To provide for old age, they thus had to acquire as much money as possible in a limited period of time.

Medical treatises provide a glimpse—but very partial and incomplete—into the daily life of prostitutes. In order to keep generating revenues, the slave-prostitutes had to avoid pregnancy at any cost. Contraceptive techniques used by the Greeks are not as well known as those of the Romans. Nevertheless, in a treatise attributed to Hippocrates (Of the Seed, 13), he describes in detail the case of a dancer "who had the habit of going with the men"; he recommends that she "jump up and down, touching her buttocks with her heels at each leap"[30] to dislodge the sperm, and thus avoid risk. Prostitutes were also probably more likely to practice infanticide than citizen women.[31] In the case of independent prostitutes the situation is less clear; girls could after all be trained "on the job", succeeding their mothers and supporting them in old age.[citation needed]

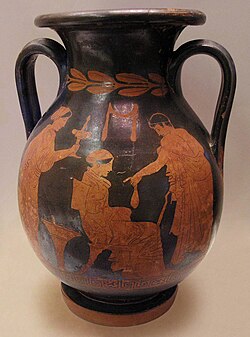

Greek pottery also provides an insight into the daily life of prostitutes. Their representation can generally be grouped into four categories: banquet scenes, sexual activities, toilet scenes and scenes depicting their maltreatment. In the toilet scenes the prostitutes are not presented as portraying the physical ideal; sagging breasts, rolls of flesh, etc.[citation needed] There is a kylix showing a prostitute urinating into a chamber pot. In the representation of sexual acts, the presence of a prostitute is often identified by the presence of a purse, which suggests the relationship has a financial component. The position most frequently shown is the leapfrog—or sodomy; these two positions being difficult to visually distinguish. The woman is frequently folded in two with her hands flat on the ground. Sodomy was considered degrading for an adult and it seems that the leapfrog position (as opposed to the missionary position) was considered less gratifying for the woman.[32] Finally, a number of vases represent scenes of abuse, where the prostitute is threatened with a stick or sandal, and forced to perform acts considered by the Greeks to be degrading: fellatio, sodomy or sex with multiple partners.[citation needed] If the hetaera were undeniably the most liberated women in Greece, it also needs to be said that many of them had a desire to become 'respectable' and find a husband or stable companion.[citation needed] Naeara, whose career is described in a legal discourse, manages to raise three children before her past as a hetaera catches up to her. According to the sources, Aspasia is chosen as concubine or possibly spouse by Pericles. Atheneus remarks that "For when such women change to a life of sobriety they are better than the women who pride themselves on their respectability"[6] (XIII, 38), and cites numerous great Greek men who had been fathered by a citizen and a courtesan, such as the Strategos Timotheus, son of Conon. Finally, there is no known example of a woman of the citizen class voluntarily becoming a hetaera. This is perhaps not surprising, since women of the citizen class would have no incentive whatsoever to do such a thing.

Prostitutes in literature

[edit]

During the time of the New Comedy (of ancient Greek comedy), prostitute characters became, after the fashion of slaves, the veritable stars of the comedies. This could be for several reasons: while Old Comedy (of ancient Greek comedy) concerned itself with political subjects, New Comedy dealt with private subjects and the daily life of Athenians. Also, social conventions forbade well-born women from being seen in public, while the plays depicted outside activities. The only women who would normally be seen out in the street were logically the prostitutes.

The intrigues of the New Comedy thus often involved prostitutes. Ovid, in his Amores, states "Whil'st Slaves be false, Fathers hard, and Bauds be whorish, Whilst Harlots flatter, shall Menander flourish."[33] (I, 15, 17–18). The courtesan could be the young girl friend of the young first star: in this case, free and virtuous, she is reduced to prostitution after having been abandoned or captured by pirates (e.g. Menander's Sikyonioi). Recognized by her real parents because of trinkets left with her, she is freed and can marry. In a secondary role, she can also be the supporting actor's love interest. Menander also created, contrary to the traditional image of the greedy prostitute, the part of the "whore with a heart of gold" in Dyskolos, where this permits a happy conclusion to the play.

Conversely, in the utopian worlds of the Greeks, there was often no place for prostitutes. In Aristophanes' play Assemblywomen, the heroine Praxagora formally bans them from the ideal city:

Why, undoubtedly! Furthermore, I propose abolishing the whores … so that, instead of them, we may have the first-fruits of the young men. It is not meet that tricked-out slaves should rob free-born women of their pleasures. Let the courtesans be free to sleep with the slaves.[34](v. 716–719).

The prostitutes are obviously considered to be unfair competition. In a different genre, Plato, in the Republic, proscribed Corinthian prostitutes in the same way as Attican pastries, both being accused of introducing luxury and discord into the ideal city. The cynic Crates of Thebes, (cited by Diodorus Siculus, II, 55–60) during the Hellenistic period describes a utopian city where, following the example of Plato, prostitution is also banished.

Male prostitution

[edit]The Greeks also had an abundance of male prostitutes, πόρνοι pórnoi.[note 6] Some of them aimed at a female clientele: the existence of gigolos is confirmed in the classical era. As such, in Aristophanes's Plutus (v. 960–1095) an old woman complains about having spent all her money on a young lover who is now jilting her. The vast majority of male prostitutes, however, were for a male clientele.

Prostitution and pederasty

[edit]Contrary to female prostitution, which covered all age groups, male prostitution was in essence restricted to adolescents. Pseudo-Lucian, in his Affairs of the Heart (25–26) expressly states:

"Thus from maidenhood to middle age, before the time when the last wrinkles of old age finally spread over her face, a woman is a pleasant armful for a man to embrace, and, even if the beauty of her prime is past, yet

"With wiser tongue Experience doth speak than can the young." But the very man who should make attempts on a boy of twenty seems to me to be unnaturally lustful and pursuing an equivocal love. For then the limbs, being large and manly, are hard, the chins that once were soft are rough and covered with bristles, and the well-developed thighs are as it were sullied with hairs.[35]"

The period during which adolescents were judged as desirable extended from puberty until the appearance of a beard, the hairlessness of youth being an object of marked taste among the Greeks. As such, there were cases of men keeping older boys for lovers, but depilated. However, these kept boys were looked down upon, and if the matter came to the attention of the public they were deprived of citizenship rights once come to adulthood. In one of his discourses (Against Timarkhos, I, 745), Aeschines argues against one such man in court, who in his youth had been a notorious escort.

As with its female counterpart, male prostitution in Greece was not an object of scandal. Brothels for slave-boys existed openly, not only in the "red-light district" of Piraeus, the Kerameikon, or the Lycabettus, but throughout the city. The most celebrated of these young prostitutes is perhaps Phaedo of Elis. Reduced to slavery during the capture of his city, he was sent to work in a brothel until noticed by Plato, who had his freedom bought. The young man became a follower of Socrates together with his mentor Plato and gave his name to the Phaedo dialogue of Plato, which relates the last hours of Socrates.[36] Males were not exempt from the city tax on prostitutes. The client of such a brothel did not receive reprobation from either the courts or from public opinion.

Prostitution and citizenship

[edit]If some portions of society did not have the time or means to practice the interconnected aristocratic rituals (spectating at the gymnasium, courtship, gifting),[note 7] they could all satisfy their desires with prostitutes. The boys also received the same legal protection from assault as their female counterparts.

As a consequence, though prostitution was legal, it was still socially shameful. It was generally the domain of slaves or, more generally, non-citizens. In Athens, for a citizen, it had significant political consequences, such as the atimia (ἀτιμία)- loss of public civil rights. This is demonstrated in The Prosecution of Timarkhos: Aeschines is accused by Timarkhos; to defend himself, Aeschines accuses his accuser of having been a prostitute in his youth. Consequentially, Timarkhos is stripped of civil rights; one of these rights being the ability to file charges against someone. Conversely, prostituting an adolescent, or offering him money for favours, was strictly forbidden as it could lead to the youth's future loss of legal status.

The Greek reasoning is explained by Aeschines (stanza 29), as he cites the dokimasia (δοκιμασία): the citizen who prostituted himself (πεπορνευμένος peporneuménos) or causes himself to be so maintained (ἡταιρηκώς hētairēkós) is deprived of making public statements because "he who has sold his own body for the pleasure of others (ἐφ’ ὕβρει eph’ hybrei) would not hesitate to sell the interests of the community as a whole". According to Polybius (XII, 15, 1), the accusations of Timaeus against Agathocles reprise the same theme: a prostitute is someone who abdicates their own dignity for the desires of another, "a common prostitute (κοινὸν πόρνον koinòn pórnon) available to the most dissolute, a jackdaw,[note 8] a buzzard[note 9] presenting his behind to whoever wants it."

Fees

[edit]As with female prostitutes, fees varied considerably. Athenaeus (VI, 241) mentions a boy who offers his favours for one obolus; again, the mediocrity of this price calls it into some doubt. Straton of Sardis, a writer of epigrams in the 2nd century, recalls a transaction for five drachma (Palatine anthology, XII, 239). In the forensic speech Against Simon, the prosecutor claimed to have hired a boy's sexual services for the price of 300 drachma, much more than what "middle range" hetaira typically charged.[37][38] And a letter of pseudo-Aeschines (VII, 3) estimates the earnings of one Melanopous at 3,000 drachma; probably through the length of his career.

The categories of male prostitution should be so separated: Aeschines, in his The Prosecution of Timarkhos (stanza 29, see above) distinguishes between the prostitute and the kept boy. He adds a little later (stanzas 51–52) that if Timarkhos had been content to stay with his first protector, his conduct would have been less reprehensible. It was not only that Timarkhos had left this man—who no longer had the funds to support him—but that he had 'collected' protectors; proving, according to Aeschines, that he was not a kept boy (hêtairêkôs), but a vulgar whore (peporneumenos).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This article was originally translated from the French Wikipedia article Prostitution en Grèce antique 22 May 2006.

- ^ The first noted occurrence of this word is found in Archilochus, a poet at the beginning of the 6th century BC(fragment 302)

- ^ The Greek εταίρα (hetaira) means literally: female companion, female mate.

- ^ One of the main tasks of these women was the processing of wool (source: [Radt,6], p. 484)

- ^ The Greek text has here a sexual pun which is hardly translatable. ιστός means: 1) (the standing posts of a) weaving loom (n.b.: ancient Greece initially knew the vertical loom); 2) mast; 3) (metonym) woven tissue. καθει̃λον ιστους means then, firstly: taking down the woven web from the loom; secondly: lowering the mast. Thirdly the hint on 'lowering' some other kind of 'mast'. (Sources: Greek dictionary, [Baladië], [Radt,2], [Radt,6])

- ^ The first recorded use of this word is in graffiti from the island of Thera(Inscriptiones Græcæ, XII, 3, 536). The second is in Aristophanes' Plutus, which dates from 390 BCE

- ^ The ἀρπαγμός harpagmos, a Cretan ritual abduction lasting supposedly two months, is hardly compatible with having full-time employment.

- ^ To the Greeks, the jackdaw or jay did not have a good reputation; hence the phrase "jays with jays", or "like attracts like", and the word is used as an insult.

- ^ In Classical Greek, the word used for buzzard was τριόρχης triórkhês—literally meaning "with three balls"; the animal wαs thus a symbol of lasciviousness.

References

[edit]- ^ "WLGR". www.stoa.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Keuls, p.154.

- ^ Philemon, The Brothers (Adelphoi), cited by the Hellenistic author Athenaeus in his book The Deipnosophists ("The Sophists at dinner"), book XIII, as cited by Laura McClure, Courtesans at table: gender and Greek literary culture in Athenaeus. (Routledge, 2003)

- ^ Burnett, Anne (2012). "Brothels, Boys, and the Athenian Adonia". Arethusa. 45 (2): 177–194. doi:10.1353/are.2012.0010. JSTOR 26322729. S2CID 162809295.

- ^ Halperin, One Hundred Years of Homosexuality, p.109.

- ^ a b of Athenaeus, Deipnosophisae. trans. Charles Burton Gulick, 1937l; accessed 19 May 2006

- ^ W. Dittenberger, Orientis Graeci inscriptiones selectæ (OGIS), Leipzig, 1903–1905, II, 674.

- ^ Ar. Thesm. 1195; Antiph. 293.3; PI. Com. 188.17

- ^ Theopomp. Com. 21: οὗ φησιν εἶναι τῶν ἑταιρῶν τὰς μέσας στατηριαίας

- ^ Epicr. 3.10-9

- ^ Aristotle in 22 vols, trans. H. Rackham [1]; accessed 20 May 2006

- ^ See, for example The Wasps by Aristophanes, v. 1342 ff.

- ^ Kurke, Leslie (1997). "Inventing the "Hetaira": Sex, Politics, and Discursive Conflict in Archaic Greece". Classical Antiquity. 16 (1): 107–108. doi:10.2307/25011056. JSTOR 25011056.

- ^ Hamel, Debra (2003). Trying Neaira: The True Story of a Courtesan's Scandalous Life in Ancient Greece. New Haven & London: Yale. p. 12.

- ^ Kapparis, Konstantinos A. (1999). Apollodoros 'Against Neaira' [D.59]. p. 6.

- ^ Kapparis, Konstantinos A. (1999). Apollodoros 'Against Neaira' [D.59]. p. 7.

- ^ McClure, Laura. "Subversive Laughter: The Sayings of Courtesans in Book 13 of Athenaeus' Deipnosophistae". The American Journal of Philology. 124 (2): 265.

- ^ See Introduction in [Baladié]. The fragment is in Geographika VIII,6,20

- ^ (in French) Trans. Jean-Paul Savignac for les éditions La Différence, 1990.

- ^ Arnaud 1973, pp. 111–115.

- ^ Assante 2003.

- ^ Budin 2008.

- ^ Budin 2008; more briefly the case that there was no sacred prostitution in Greco-Roman Ephesus Baugh 1999; see also the book review by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, April 28, 2009 Archived 12 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Rickard 2015.

- ^ Ipsen 2014.

- ^ a b Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- ^ Conrad M. Stibbe, Lakonische Vasenmaler des sechtsen Jahrhunderts v. Chr., Number 191 (1972), pl. 58. Cf. Maria Pipili, Laconian Iconography of The Sixth Century BC, Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph, Number 12, Oxford, 1987.

- ^ a b Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 109.

- ^ Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 119.

- ^ Hippocrates. De semine/natura pueri trans. Iain Lonie, in David Halperin. One Hundred Years of Homosexuality; And Other Essays on Greek Love. Routledge, 1989. ISBN 0-415-90097-2

- ^ Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves 1994 [1975] p.91.

- ^ Cf. Eva C. Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus, ch. 6 "The Athenian Prostitute", pp. 174–179.

- ^ Ovid, Amores, trans Christopher Marlowe; accessed 21 May 2006

- ^ Aristophanes. Ecclesiazusae. The Complete Greek Drama, vol. 2. Eugene O'Neill, Jr. New York. Random House. 1938; accessed 21 May 2006

- ^ Pseudo-Lucian, Affairs of the Heart, trans. A.M. Harmon (Loeb edition)

- ^ Cited in Diogenes Laërtius, II, 31.

- ^ Konstantinos Kapparis (2018). Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World. De Gruyter. p. 215. ISBN 978-3110556759.

- ^ Laurie O'Higgins (2007). Women and Humor in Classical Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0521037907.

Sources

[edit]- Arnaud, Daniel (1973). "La prostitution sacrée en Mésopotamie, un mythe historiographique?". Revue de l'Histoire des Religions (183): 111–115.

- Assante, Julia (2003). "From Whores to Hierodules: the Historiographic Invention of Mesopotamian Female Sex Professionals". In Donohue, A. A.; Fullerton, Mark D. (eds.). Ancient Art and its Historiography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815673.

- (in French) [Baladié] Strabon. Géographie. Tome V. (Livre VIII). Texte établi et traduit par Raoul Baladié, Professeur à l’Université de Bordeaux III. Société d’édition « Les Belles Lettres », Paris; 1978.

- Baugh, S. M. (September 1999). "Cult Prostitution In New Testament Ephesus: A Reappraisal". Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 42 (3): 443–460.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2008). The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521880909.

- Ipsen, Avaren (2014). Sex Working and the Bible. Routledge. ISBN 9781317490661.

- (in German) [Radt,2] Strabons Geographika. Band 2: Buch V-VIII: Text und Übersetzung. Mit Übersetzung und Kommentar herausgegeben von Stefan Radt. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen; 2003.

- (in German) [Radt,6] Stefan Lorenz Radt – Strabons Geographika. Band 6: Buch V-VIII: Kommentar. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen; 2007.

- Rickard, Kelley (2015). "A Brief Study into Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity". ResearchGate.

Further reading

[edit]- David M. Halperin, « The Democratic Body; Prostitution and Citizenship in Classical Athens », in One Hundred Years of Homosexuality and Other Essays on Greek Love, Routledge, "The New Ancient World" collection, London-New York, 1990 ISBN 0-415-90097-2

- Kenneth J. Dover, Greek Homosexuality, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Massachusetts), 1989 (1st edition 1978). ISBN 0-674-36270-5

- Eva C. Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1993. ISBN 0-520-07929-9

- Sarah B. Pomeroy, Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity, Schocken, 1975. ISBN 0-8052-1030-X

- (in German) K. Schneider, Hetairai, in Paulys Real-Encyclopädie der classichen Altertumwissenschaft, cols. 1331–1372, 8.2, Georg Wissowa, Stuttgart, 1913

- (in French) Violaine Vanoyeke, La Prostitution en Grèce et à Rome, Les Belles Lettres, "Realia" collection, Paris, 1990.

- Hans Licht, Sexual Life in Ancient Greece, London, 1932.

- Allison Glazebrook, Madeleine M. Henry (ed.), Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 BCE-200 CE (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011) (Wisconsin studies in classics).