New Zealanders

| |

A group of young New Zealanders at a climate change protest in Wellington, 2019 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 5.8 million

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 5,340,000 | |

| 640,770[1] | |

| 58,286[2] | |

| 22,872[2] | |

| 17,485[3] | |

| 4,260[2] | |

| 4,000[4] | |

| 3,146[2] | |

| 3,000[5] | |

| 2,631[6][7] | |

| 2,195[2] | |

| 1,400[8] | |

| 1,256[9] | |

| 4,000 | |

| Languages | |

| English · Te Reo Māori · Other minority languages | |

| Religion | |

| Plurality: Irreligious Minority: Christianity (Anglican, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism) and other minority religions[10] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Australians, Britons | |

New Zealanders (Māori: Tāngata Aotearoa) are people associated with New Zealand, sharing a common history, culture, and language (New Zealand English). People of various ethnicities and national origins are citizens of New Zealand, governed by its nationality law.

Originally composed solely of the indigenous Māori, the ethnic makeup of the population has been dominated since the 19th century by New Zealanders of European descent, mainly of English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish ancestry, with smaller percentages of other European and Middle Eastern ancestries such as Greek, Turkish, Italian and other groups such as Arab, German, Dutch, Scandinavian, South Slavic and Jewish, with Western European groups predominating. Today, the ethnic makeup of the New Zealand population is undergoing a process of change, with new waves of immigration, higher birth rates and increasing interracial marriage resulting in the New Zealand population of Māori, Asian, Pasifika and multiracial descent growing at a higher rate than those of solely European descent, with such groups projected to make up a larger proportion of the population in the future.[11] New Zealand has an estimated resident population of around 5,338,500 (as of June 2024).[12] Over one million New Zealanders recorded in the 2013 New Zealand census were born overseas, and by 2021 over a quarter of New Zealanders are estimated to be foreign born.[13] Rapidly increasing ethnic groups vary from being well-established, such as Indians and Chinese, to nascent ones such as African New Zealanders.[14]

While most New Zealanders are resident in New Zealand, there is also a significant diaspora, estimated at around 750,000. Of these, about 640,800 lived in Australia (a June 2013 estimate[update]),[1] which was equivalent to 12% of the resident population of New Zealand. Other communities of New Zealanders abroad are heavily concentrated in other English-speaking countries, specifically the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada, with smaller numbers located elsewhere.[2] New Zealanders have had a cultural influence on a global scale, through film, language, te ao Māori, art, science, music and technology, and founded the modern women's suffrage and anti-nuclear movements. Technological and scientific achievements of New Zealanders stem back as far as Kupe and the earliest Polynesian navigators, who used sophisticated astral methods that helped laid the groundwork for both navigation and modern astronomy.[15] Modern trench warfare is often argued to have originated in New Zealand among Māori in the 19th century.[16] New Zealanders also pioneered nuclear physics (Ernest Rutherford),[17] the women's suffrage movement (Kate Sheppard), modern Western conceptions of gender identity (John Money) and plastic surgery (Harold Gillies).[18]

New Zealand culture is essentially a Western culture influenced by the unique environment and geographic isolation of the islands, and the cultural input of the Māori and the various waves of multiethnic migration which followed the British colonisation of New Zealand. A colloquial name for New Zealanders is a Kiwi (/kiːwiː/).[19][20][21]

Ethnic origins

[edit]| 1961 New Zealand census[22][23] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | Population | % of New Zealand population | |||

| European | 2,216,886 | 91.8 | |||

| Māori | 167,086 | 6.9 | |||

| Other | 31,012 | 1.3 | |||

| Total | 2,414,984 | 100.0 | |||

| 2013 New Zealand census[24][25] | |||||

| Ethnic group | Population | % of New Zealand population | |||

| European | 2,969,391 | 74.0 | |||

| Māori | 598,602 | 14.9 | |||

| Asian | 471,708 | 11.8 | |||

| Pacific Islander | 295,941 | 7.4 | |||

| ME/LA/African | 46,956 | 1.2 | |||

| Other | 67,752 | 1.7 | |||

| Total | 4,242,048 | 100.0 | |||

The table above shows the broad ethnic composition of the New Zealand population at the 1961 census compared to that from the most recent data of the 2013 census. People of European descent constituted the majority of the 4.2 million people living in New Zealand, with 2,969,391 or 74.0% of the population in the 2013 New Zealand census.[25] Those of full or part-Māori ancestry comprise 14.9% of New Zealanders. The residual "others" ethnic group consists largely of Asians and Pacific Islanders.[22]

Māori

[edit]

The Māori people are most likely descended from people who emigrated from Taiwan to Melanesia and then travelled east through to the Society Islands.[26] After a pause of 70 to 265 years, a new wave of exploration led to the discovery and settlement of New Zealand in about AD 1250–1300,[27] making New Zealand one of the most recently settled major landmasses. Some researchers have suggested an earlier wave of arrivals dating to as early as AD 50–150; these people then either died out or left the islands.[28][29][30]

Over the following centuries the Polynesian settlers developed into a distinct culture now known as Māori. The population was divided into iwi (tribes) and hapū (subtribes) which would cooperate, compete and sometimes fight with each other. At some point a group of Māori migrated to the Chatham Islands where they developed their distinct Moriori culture.[31][32]

Due to New Zealand's geographic isolation, 500 years passed before the next phase of settlement, the arrival of Europeans. Only then did the indigenous inhabitants need to distinguish themselves from the new arrivals, using the term "Māori" which means "normal" or "ordinary".[33]

Between the mid-1840s through to the 1860s, disputes over questionable land purchases led to the New Zealand Wars, which resulted in large tracts of tribal land being confiscated by the colonial government. Settlements such as Parihaka in Taranaki have become almost legendary because of injustices done there.[34] With the loss of much of their land coupled with high fatality rate due to introduced diseases and epidemics, Māori went into a period of decline, and in the late 19th century it was believed that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race and would be assimilated into the European population.

However, the predicted decline did not occur, and numbers recovered. Despite a high degree of intermarriage between Māori and European populations, Māori were able to retain their cultural identity and in the 1960s and 1970s Māoridom underwent a cultural revival.[35]

The Māori population has seen stability in the 21st century. In the 2013 Census, 598,602 people identified as being part of the Māori ethnic group, accounting for 14.9%[24] of the New Zealand population, while 668,724 people (17.5%) claimed Māori descent.[24] 278,199 people identified as of sole Māori ethnicity, while 291,015 identified as of both European and Māori ethnicity (with or without a third ethnicity), due to a high rate of intermarriage between the two cultures.[36] Under the Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1974, a Māori is defined as "a person of the Māori race of New Zealand; and includes any descendant of such a person", replacing an earlier legal application based on an arbitrarily defined "degree of Maori [sic] blood".[37]

According to the 2006 census, the largest iwi by population is Ngāpuhi (125,601), followed by Ngāti Porou (71,049), Ngāi Tahu (54,819) and Waikato (40,083). However, over 110,000 people of Māori descent in the 2013 census could not identify their iwi.[24] Outside of New Zealand, a large Māori population exists in Australia, estimated at 155,000 in 2011.[38] The Māori Party has suggested a special seat should be created in the New Zealand parliament representing Māori in Australia.[39] Smaller communities also exist in the United Kingdom (approx. 8,000), the United States (up to 3,500) and Canada (approx. 1,000).[40][41]

The most common region this group lived in was Auckland Region (23.9 percent or 142,770 people). They are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders. In addition, more than 120,000 Māori live in Australia. The Māori language (known as Te Reo Māori) is still spoken to some extent by about a fifth of all Māori, representing 3% of the total population. Many New Zealanders regularly use Māori words and expressions, such as "kia ora", while speaking English. Māori are active in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, with independent representation in areas such as media, politics and sport.

European

[edit]

Most European New Zealanders have British and/or Irish ancestry, with smaller percentages of other European ancestries such as Germans, Poles (historically noted as "Germans" due to Partitions of Poland), French, Dutch, Scandinavian and South Slavs.[42] In 1961, the census showed that 91.8% of New Zealanders self-identified as being of European descent, down from 95% in 1926.[22]

The Māori-language loanword Pākehā came into use to refer to European New Zealanders, although some European New Zealanders reject this appellation.[43][44] Twenty-first century New Zealanders increasingly use the word "Pākehā" to refer to all non-Polynesian New Zealanders.[45]

The first Europeans known to have reached New Zealand were the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman and his crew in 1642.[46] Māori killed several of the crew, and no more Europeans went to New Zealand until British explorer James Cook's voyage of 1768–71.[46] Cook reached New Zealand in 1769 and mapped almost the entire coastline. Following Cook, New Zealand was visited by numerous European and North American whaling, sealing, exploring and trading ships. They traded European food and goods, especially metal tools and weapons, for Māori timber, food, artefacts and water. On occasion, Europeans and Māori traded goods for sex.[47] Some early European arrivals integrated closely with the indigenous Māori people and became known as Pākehā Māori. James Belich characterises many of the very early European settlers as forerunners of a "crew culture" – as distinct from the majority of later European immigrants.[48]

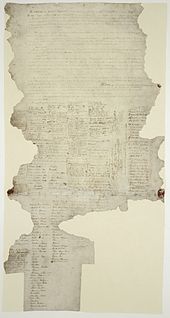

The Treaty of Waitangi was first signed in the Bay of Islands on 6 February 1840.[49] Confusion and disagreement continue to surround the Treaty. However, most New Zealanders still regard "the Treaty" as marking New Zealand's foundation as a nation.

In response to attempts by the New Zealand Company to establish a separate colony in Wellington, and mindful of French claims in Akaroa, Hobson, appointed as Lieutenant-Governor on 14 January 1840, declared British sovereignty over all of New Zealand on 21 May 1840. He published two proclamations published in the New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette issue of 19 June 1840. One "assert[s] on the grounds of Discovery, the Sovereign Rights of Her Majesty over the Southern Islands of New Zealand, commonly called 'The Middle Island' (South Island) and 'Stewart's Island' (Stewart Island / Rakiura); and the Island, commonly called 'The Northern Island', having been ceded Sovereignty to Her Majesty". The second proclamation expanded on how sovereignty over the "Northern Island" had been ceded under the treaty signed that February.[50]

Following the formalising of sovereignty, an organised and structured flow of migrants from Great Britain and Ireland began, and by 1860 more than 100,000 British and Irish settlers lived throughout New Zealand. The Otago Association actively recruited settlers from Scotland, generating a definite Scottish influence in Murihiku, while the Canterbury Association recruited settlers from the south of England, giving a definite English influence to the "Canterbury Settlement".[51] By 1870 the non-Māori population reached over 250,000.[52]

Other settlers came from Germany, Scandinavia, and other parts of Europe as well as from China and the Indian subcontinent, but British and Irish settlers made up the vast majority, and did so for the next 150 years.[21]

Between 1881 and the 1920s, the New Zealand Parliament passed legislation that intended to limit Asiatic migration to New Zealand, and prevented Asians from naturalising.[53] In particular, the New Zealand government levied a poll tax on Chinese immigrants up until the 1930s, when Japan went to war with China. New Zealand finally abolished the poll tax in 1944. An influx of Jewish refugees from central Europe came in the 1930s. Many of the persons of Polish origin in New Zealand arrived as orphans from Eastern Poland via Siberia and Iran in 1944 during World War II.[54]

Post-WWII European immigration

[edit]

With the agencies of the United Nations dealing with humanitarian efforts following the Second World War, New Zealand accepted about 5,000 refugees and displaced persons from Europe, and more than 1,100 Hungarians between 1956 and 1959 (see Refugees in New Zealand).[55] The post-WWII immigration included more persons from Greece, Italy, Poland and the former Yugoslavia.[56]

New Zealand limited immigration to those who would meet a labour shortage in New Zealand. To encourage those to come, the Government introduced free and assisted passages in 1947, a schema expanded by the First National Government in 1950.[citation needed] However, when it became clear that not enough skilled migrants would come from the British Isles alone, recruitment began in Northern European countries. New Zealand signed a bilateral agreement for skilled migrants with the Netherlands, and a large number of Dutch immigrants arrived in New Zealand. Others came in the 1950s from Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Austria to meet needs in specialised occupations. By the 1960s, the policy of excluding people based on nationality yielded a population overwhelmingly European in origin. By the mid-1960s, a desire for cheap unskilled labour led to ethnic diversification.

Asian

[edit]

In the 2013 Census, Asian ancestries total was 11.8% of the population, Chinese remained the largest Asian ethnic group in 2013, with 171,411 people while Indian was the second-largest Asian ethnic group in 2013, with 155,178 with Filipino a distant third with 40,350 people.[24]

The Asian component actually predates the Pacific component. There had been people of Asian ethnicity living in New Zealand from the early days of European settlement, albeit in very small numbers. During the period of gold rushes later in the nineteenth century the number of Chinese temporary settlers both from China and from Australia and America increased sharply. This was an interlude in many respects, though there was a small population which remained and settled permanently. However, a century later in the 1980s and 1990s the number of people of Asian ethnicities grew rapidly, and they are likely to exceed the Pacific population within the next few years.

Pacific Islanders

[edit]

In the 1950s and 1960s, New Zealand encouraged migrants from the South Pacific.[57] The country had a large demand for unskilled labour in the manufacturing sector. As long as this demand continued, migrants were encouraged by the government to come from the South Pacific, and many overstayed. However, when the boom times stopped, some blamed the migrants for the economic downturn affecting the country, and many of those people suffered dawn raids from 1974.[58][59]

Middle Eastern, Latin American and African

[edit]This component was 1.2% of the total population in the 2013 census.[24] The Latin American ethnic group almost doubled in size between the 2006 and 2013 censuses, increasing from 6,654 people to 13,182. A more recent component comprises refugees and other settlers from Africa and the Middle East, most recently from Somalia. While there had been previous settlers from the Middle East, such as Syrians, people from Equatorial Africa have been very few in the past.

- Middle Eastern ethnic group – 20,406

- African ethnic group – 13,464

Others

[edit]In 2013, 67,752 people or 1.7% self-identified with one or more ethnicities other than European, Māori, Pacific, Asian, Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African. The vast majority of these people, 65,973 people, identified only as 'New Zealander'.[24][60]

Race and ethnic relations

[edit]

After 1840, many issues to do with sovereignty and land ownership remained unresolved and, for a long time, invisible while Māori lived in rural communities. When Māori and Pākehā (Europeans) began living in closer proximity, the belief that the country had "the best race relations in the world" was tested. The first Race Relations Concilitator was appointed in 1971 to help combat racial discrimination among New Zealanders.[61]

Agitation regarding Treaty of Waitangi violations intensified in the 1970s. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975 to consider alleged breaches, and in 1984 was empowered to look back to 1840.[62]

In general, New Zealanders of European descent consider themselves to be mostly free of racial prejudice, perceiving the country to be a more inclusive society, a notion that has been challenged especially by members of ethnic minority groups. According to research published in 2018, which analysed New Zealand adults' reported experience of racism over a 10-year period, reported recent racist experiences were highest among Asian participants followed by Māori and Pacific peoples, with Europeans reporting the lowest experience of racism.[63]

Culture

[edit]New Zealand culture is essentially a Western culture influenced by the unique environment and geographic isolation of the islands, and the cultural input of the Māori and the various waves of multiethnic migration which followed the British colonisation of New Zealand. British settlers brought a legal, political, and economic system that has flourished, along with the British system of agriculture that has transformed the landscape.

The development of a New Zealand identity and national character, separate from the British colonial identity, is most often linked with the period surrounding the First World War, which gave rise to the concept of the Anzac spirit.[64] However, cultural links between New Zealand and Great Britain are maintained by a common language, sustained immigration from the UK, and the fact that many young New Zealanders spend time in Britain on "overseas experience", known as "OE".[65] New Zealanders also identify closely with Australians, as a result of the two nations' shared historical, cultural and geographic characteristics.[66]

The New Zealand government promotes Māori culture by supporting Māori-language schools, by ensuring the language is visible in government departments and literature, by insisting on traditional Māori welcomes (pōwhiri) at government functions and state school award programs,[67] and by having Māori run the welfare services targeted at their people.[68]

New Zealanders are distinctive for their twangy dialect of English and propensity to travel long distances, and are quickly associated with the All Blacks rugby team and the haka. A tradition of resourcefulness came from the pioneering backgrounds of both Māori and non-Māori.

National personifications

[edit]

Zealandia is a national personification of New Zealand and New Zealanders. In her stereotypical form, Zealandia appears as a woman of European descent who is dressed in flowing robes (or gown).[69][70] She is similar in dress and appearance to Britannia (the female personification of Britain), who is said to be the mother of Zealandia.[70]

As a rhetorical evocation of a New Zealand national identity,[69] Zealandia appeared on postage stamps, posters, cartoons, war memorials, and New Zealand government publications most commonly during the first half of the 20th century. The personification was a commonly used symbol of the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition, which was held in Wellington in 1939 and 1940.[69] Two large Zealandia statues serve as war memorials that honour the casualties of the Second Boer War: one is in Waimate and the other is in Palmerston.[69] Some smaller statues exist in museums and in private hands.

The female figure who appears on the left side of the national coat of arms has been identified as Zealandia[71] (in a "cut down nightie").[70]

Inventions

[edit]Māori, and other Polynesians, have been credited by many historians as being the world's foremost navigators prior to the modern age.[72][73] Polynesians made contact with nearly every island within the vast Polynesian Triangle, inventing the catamaran and conceiving some of the most complex astronomy in the world to help navigate the Pacific. The continuance of this knowledge after the immediate settlement of New Zealand is evident in the non-tangible 360° compass developed and used by Māori long before European settlement. Māori compasses were divided into 32 different whare, or houses, between north, south, east, and west. This helped navigators memorise upwards of 200 stars. Memorisation was integral to Māori knowledge, which had no written language.[74] Oral tradition was maintained in New Zealand by guilds for centuries after Māori arrival, despite later colonial efforts to suppress it.

In the New Zealand Wars (1845–1872), the Māori developed elaborate trench and bunker systems as part of the already-existent fortified areas known as pā, employing them successfully as early as the 1840s to withstand British artillery bombardments.[75][76] These systems included firing trenches, communication trenches, tunnels, and anti-artillery bunkers. The Ngāpuhi pā Ruapekapeka is often considered to be the most technologically impressive by historians, and was described in 2017 as "one of the most sophisticated military installations" the British Empire had ever tackled, by broadcaster Mihingarangi Forbes for RNZ.[77][78] There has been an academic debate surrounding this since the 1980s, when in his book The New Zealand Wars, historian James Belich claimed that Northern Māori had effectively invented trench warfare during the first stages of the New Zealand Wars. However, given that trenches of some form or another have always been present in human warfare, this conclusion has been contentious and criticised by other historians.[79]

New Zealanders in the modern era have been prolific innovators. Instant coffee, today a staple drink across the world, was first invented in Invercargill in 1890 by food chemist David Strang.[80] Katherine Sheppard, a suffragette, is regarded as the mother of the modern women's suffrage movement. Her efforts within the Women's Christian Temperance Union New Zealand led to New Zealand becoming the first nation in the world to enact universal suffrage.

Sexologist John Money, recognised today as a contentious figure for his experiments regarding children and the David Reimer case, was a pioneer of modern gender identity studies. Money's theory that gender is learnt has become outdated and even condemned,[81] although his terms gender role and sexual orientation remain common in modern parlance. He also established the Johns Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic, the first clinic in the United States to perform sexual reassignment surgeries.[82][83] Surgeon and otolaryngologist Harold Gillies is regarded as the father of modern plastic surgery, which he pioneered on soldiers physically dismembered beyond regular care during the First World War.[18][84]

Language

[edit]English (New Zealand English) is the dominant language spoken by New Zealanders, and a de facto official language of New Zealand. According to the 2013 New Zealand census,[85] 96.1% of New Zealanders spoke English. The country's de jure official languages are Māori (Te Reo) and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL). Other languages are also used by ethnic communities.

Religion

[edit]

Just under half of the population at the 2013 census[85] declared an affiliation to Christianity. However, regular church attendance is probably closer to 15%.[86] Before European colonisation the religion of the indigenous Māori population was animistic, but the subsequent efforts of missionaries such as Samuel Marsden resulted in many Māori converting to Christianity.

Religious affiliation has been collected in the New Zealand census since 1851. One of the many complications in interpreting religious affiliation data in New Zealand is the large proportion who object to answering the question, roughly 173,000 in 2013. Most reporting of percentages is based on the total number of responses, rather than the total population.

See also

[edit]- Kiwi (nickname)

- Demographics of New Zealand

- Lists of New Zealanders

- List of prime ministers of New Zealand

References

[edit]- ^ a b Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection (2 January 2014). "Fact Sheet 17 – New Zealanders in Australia". Archived from the original on 12 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f John Bryant and David Law (September 2004). "New Zealand's Diaspora and Overseas-born Population: The diaspora". New Zealand Treasury. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ "Immigrant status and period of immigration by place of birth and citizenship: Canada, provinces and territories and census metropolitan areas with parts". Statistics Canada. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ Matthew Chung (6 November 2009). "From F1 to Fifa, the show rolls on". The National. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "Living in Hong Kong". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland (Stand: 31. Dezember 2014)".

- ^ "Pressemitteilungen – Ausländische Bevölkerung – Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis)" (in German). Destatis.de. 29 March 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Erwin Dopf. "Présentation de la Nouvelle-Zélande, Relations bilatérales". diplomatie.gouv.fr. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "Imigrantes internacionais registrados no Brasil". www.nepo.unicamp.br. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "2018 Census totals by topic" (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet). Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Gillian Smeith and Kim Dunstan (June 2004). "Ethnic Population Projections: Issues and Trends". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ "Aotearoa Data Explorer". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Number of overseas-born tops 1 million, 2013 Census shows". Statistics New Zealand. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Walrond, Carl (2015). "Africans". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Vermillion, Stephanie. "Polynesia's master voyagers who navigate by nature". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Ruapekapeka". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Ernest Rutherford | Accomplishments, Atomic Theory, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Walter Ernest O'Neil Yeo – One of the first people to undergo Plastic Surgery". The Yeo Society. 28 August 2008.

- ^ "Definition of 'kiwi'". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Gary Morley (24 June 2010). "Kiwis hope to take flight at World Cup". CNN. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Kiwi and people: early history". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ a b c "The Population of New Zealand" (PDF). cicred. 1974. p. 53. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

TOTAL POPULATION BY ETHNIC ORIGIN 1916–1971 The New Zealand population can broadly be classified, according to ethnic origin, into three main groups: Europeans, Maoris and "others"

- ^ "Total and Mäori Populations 1858–2001 Censuses of Population and Dwellings" (PDF). Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g 2013 Census QuickStats about culture and identity Archived 15 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine Available from stats.govt.nz.

- ^ a b 2013 Census results: New Zealand

- ^ Wilmshurst, J. M.; Hunt, T. L.; Lipo, C. P.; Anderson, A. J. (2010). "High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (5): 1815–20. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.1815W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015876108. PMC 3033267. PMID 21187404.

- ^ Irwin, Geoff; Walrond, Carl (4 March 2009). "When was New Zealand first settled? – The date debate". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Mein Smith (2005), pg 6.

- ^ Lowe, David J. (2008). Lowe, David J. (ed.). Guidebook for Pre-conference North Island Field Trip A1 'Ashes and Issues' (28–30 November 2008). Australian and New Zealand 4th Joint Soils Conference, Massey University, Palmerston North (1–5 December 2008) (PDF). New Zealand Society of Soil Science. pp. 142–147. ISBN 978-0-473-14476-0. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ^ Sutton et al. (2008), pg 109. "This paper ... affirms the Long Chronology [first settlement up to 2000 years BP], recognizing it as the most plausible hypothesis."

- ^ Clark (1994) pg 123–135

- ^ Davis, Denise (11 September 2007). "The impact of new arrivals". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Hare, McLintock, Alexander; Gully, John Sidney (1966). "The Word 'Maori'". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Parihaka Attack". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Māori – Urbanisation and renaissance". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ "Ethnic group (detailed single and combination) by age group and sex, for the census usually resident population count, 2013". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ "Maori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 (1974 No 73)". www.nzlii.org. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Hamer, Paul (2012), Māori in Australia: An Update from the 2011 Australian census and the 2011 New Zealand General Election, SSRN 2167613

- ^ "Sharples suggests Maori seat in Australia". Television New Zealand. 1 October 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ Walrond, Carl (4 March 2009). "Māori overseas". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ New Zealand-born figures from the 2000 U.S. Census; maximum figure represents sum of "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" and people of mixed race. United States Census Bureau (2003)."Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles (STP-159): Country of Birth: New Zealand" (PDF). (103 KB). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand: New Zealand Peoples Archived 20 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Misa, Tapu (8 March 2006). "Ethnic Census status tells the whole truth". New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Draft Report of a Review of the Official Ethnicity Statistical Standard: Proposals to Address the 'New Zealander' Response Issue" (PDF). Statistics New Zealand. April 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Ranford, Jodie. "'Pakeha', Its Origin and Meaning". Māori News. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

Originally the Pakeha were the early European settlers, however, today 'Pakeha' is used to describe any peoples of non-Maori or non-Polynesian heritage. [...] It is merely a means by which the peoples of Aotearoa differentiate between the indigenous peoples and the early European Settlers, or the Maori and the other, irrelevant of race, colour, ethnicity, and culture.

- ^ a b Mein Smith (2005), pg 23.

- ^ King (2003) pg 122.

- ^

Belich, James (1996). Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders From Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century. Auckland: Penguin (published 2007). ISBN 9781742288222. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

Old New Zealand did not finally fade away until the early twentieth century, but in the half-century before this it was largely transformed into what a later chapter will call 'crew culture'. This culture differed sharply from mainstream Pakeha society, shared many of the characteristics of the Old New Zealand Tasmen, and was their heir. But it tended more to miners and navvies than whalers and sealers; was much larger; worked more in tandem with mainstream Pakeha; and from the 1860s was increasingly disconnected from its old Maori partner.

- ^ Political and constitutional timeline, New Zealand History online, Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Updated 6 December 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette". Hocken Library. 19 June 1840. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ^ "History of Immigration – 1840 – 1852". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "History of Immigration – 1853 – 1870". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "1881–1914: restrictions on Chinese and others". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "Polish Orphans — Refugees". 16 November 2012 – via Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

The photo shows some of them on board the General G. Randall on the day they arrived.

- ^ "The 1950s – Overview". nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 1 May 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ "History of Immigration – 1840 – 1852". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "Pacific Islands and New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ Anae, Melanie (2012). "Overstayers, Dawn Raids and the Polynesian Panthers". In Sean, Mallon (ed.). Tangata O Le Moana: New Zealand and the People of the Pacific. Te Papa Press. pp. 227–30. ISBN 978-1-877385-72-8.

- ^ Damon Fepulea'I, Rachel Jean, Tarx Morrison (2005). Dawn Raids (documentary). Television New Zealand, Isola Publications.

- ^ 2013 Census tables about a place: New Zealand Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ethnic groups of people in New Zealand

- ^ "The people of New Zealand". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "About the Waitangi Tribunal". waitangitribunal.govt.nz. Waitangi Tribunal. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Harris, Ricci B.; Stanley, James; Cormack, Donna M. (3 May 2018). "Racism and health in New Zealand: Prevalence over time and associations between recent experience of racism and health and wellbeing measures using national survey data". PLOS ONE. 13 (5): e0196476. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1396476H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0196476. PMC 5933753. PMID 29723240.

- ^ "The Spirit of ANZAC". ANZAC Day Commemoration Committee. 26 November 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Make your overseas experience relevant to New Zealand". newzealandnow.govt.nz. New Zealand Immigration. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Australia and New Zealand – Common culture". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Haerewa, Ngarangi (17 August 2016). "Māori Culture: What Is A Pōwhiri?". Culture Trip. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ Gray, Mel; Coates, John; Bird, Michael Yellow (2008). Indigenous Social Work Around the World: Towards Culturally Relevant Education and Practice. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 114. ISBN 9780754648383.

- ^ a b c d Wolfe, Richard (July–September 1994). "Zealandia – mother of the nation?". New Zealand Geographic. No. 23. Auckland. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Denis James Matthews Glover, "A National Symbol?" in An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand (A. H. McLintock ed, 1966). Retrieved on 5 June 2017.

- ^ National Arms of New Zealand – Heraldry of the World. Last modified on 21 January 2016. Retrieved on 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Polynesia's Genius Navigators". PBS. 15 February 2000. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "How did Polynesian wayfinders navigate the Pacific Ocean? – Alan Tamayose and Shantell De Silva". TED-Ed. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Te Kāpehu Whētu- The Māori Star Compass | by Education at Waitangi". www.waitangi.org.nz. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ Cowen, James (1955). "Chapter 7: The Attack on Ohaeawai". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period (1845–1864). Vol. I. Wellington: R.E. Owen, Government Printer.

- ^ "Early Maori military engineering skills to be honoured by New Zealand Professional Engineers". New Zealand Department of Conservation. 14 February 2008. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "NZ WARS – The Stories of Ruapekapeka". RNZ. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ "NZ WARS – The Stories of Ruapekapeka". RNZ. 25 October 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2023.

- ^ "Ruapekapeka | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "First Annual Report". Patents, Designs and Trade-marks. New Zealand. 1890. p. 9.

- ^ "Dr. Money and the Boy With No Penis". Horizon. Season 41. Episode 8. 4 November 2004. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ Ehrhardt, Anke A. (August 2007). "John Money, PhD". The Journal of Sex Research. 44 (3): 223–224. doi:10.1080/00224490701580741. JSTOR 20620298. PMID 3050136. S2CID 147344556.

- ^ Tosh, Jemma (25 July 2014). Perverse Psychology: The pathologization of sexual violence and transgenderism. Routledge. ISBN 9781317635444.

- ^ The birth of plastic surgery National Army Museum website

- ^ a b Table 28, 2013 Census Data – QuickStats About Culture and Identity – Tables.

- ^ Opie, Stephen (June 2008). Bible Engagement in New Zealand: Survey of Attitudes and Behaviour (PDF). Bible Society of New Zealand. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

External links

[edit]- Demographics of New Zealand's Pacific Population—Statistics New Zealand

- Population clock—Statistics New Zealand