Pear

| Pear | |

|---|---|

| |

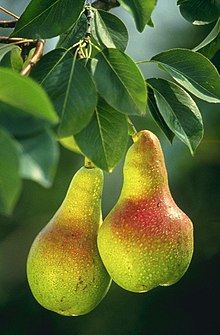

| European pear branch with two pears | |

| |

| Pear fruit cross section | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Subfamily: | Amygdaloideae |

| Tribe: | Maleae |

| Subtribe: | Malinae |

| Genus: | Pyrus L. |

| Species | |

|

About 30 species; see text | |

Pears are fruits produced and consumed around the world, growing on a tree and harvested in late summer into mid-autumn. The pear tree and shrub are a species of genus Pyrus /ˈpaɪrəs/, in the family Rosaceae, bearing the pomaceous fruit of the same name. Several species of pears are valued for their edible fruit and juices, while others are cultivated as trees.

The tree is medium-sized and native to coastal and mildly temperate regions of Europe, North Africa, and Asia. Pear wood is one of the preferred materials in the manufacture of high-quality woodwind instruments and furniture.

About 3,000 known varieties of pears are grown worldwide, which vary in both shape and taste. The fruit is consumed fresh, canned, as juice, dried, or fermented as perry.

Etymology

[edit]The word pear is probably from Germanic pera as a loanword of Vulgar Latin pira, the plural of pirum, akin to Greek apios (from Mycenaean ápisos),[1] of Semitic origin (pirâ), meaning "fruit". The adjective pyriform or piriform means pear-shaped.[2] The classical Latin word for a pear tree is pirus;[3] pyrus is an alternate form of this word sometimes used in medieval Latin.[4]

Description

[edit]

The pear is native to coastal, temperate, and mountainous regions of the Old World, from Western Europe and North Africa east across Asia.[5][6] They are medium-sized trees, reaching up to 20 m tall, often with a tall, narrow crown; a few pear species are shrubby.[7][8]

The leaves are alternately arranged, simple, 2–12 cm (1–4+1⁄2 in) long, glossy green on some species, densely silvery-hairy in some others; leaf shape varies from broad oval to narrow lanceolate.[8] Most pears are deciduous, but one or two species in Southeast Asia are evergreen.[8][9] Some pears are cold-hardy, withstanding temperatures as low as −25 to −40 °C (−13 to −40 °F) in winter, but many grown for agriculture are vulnerable to cold damage.[5][10] Evergreen species only tolerate temperatures down to about −12 °C (10 °F).[11]

The flowers are white, rarely tinted yellow or pink, 2–4 centimetres (1–1+1⁄2 in) diameter, and have five petals, five sepals, and numerous stamens.[8][12] Like that of the related apple, the pear fruit is a pome, in most wild species 1–4 cm (1⁄2–1+1⁄2 in) diameter, but in some cultivated forms up to 18 cm (7 in) long and 9 cm (3+1⁄2 in) broad.[8] The shape varies in most species from oblate or globose, to the classic pyriform "pear shape" of the European pear with an elongated basal portion and a bulbous end.[10]

The fruit is a pseudofruit composed of the receptacle or upper end of the flower stalk (the so-called calyx tube) greatly dilated.[8] Enclosed within its cellular flesh is the true fruit: 2–5 'cartilaginous' carpels,[5][13] known colloquially as the "core".[8]

Pears and apples cannot always be distinguished by the form of the fruit;[14] some pears look very much like some apples, e.g. the nashi pear.[7][15]

History

[edit]

Pear cultivation in temperate climates extends to the remotest antiquity, and evidence exists of its use as a food since prehistoric times. Many traces have been found in prehistoric pile dwellings around Lake Zurich.[16] Pears were cultivated in China as early as 2000 BC.[17] An article on Pear tree cultivation in Spain is brought down in Ibn al-'Awwam's 12th-century agricultural work, Book on Agriculture.[18]

The word pear, or its equivalent, occurs in all the Celtic languages, while in Slavic and other dialects, differing appellations still referring to the same thing are found—a diversity and multiplicity of nomenclature, which led Alphonse Pyramus de Candolle to infer a very ancient cultivation of the tree from the shores of the Caspian to those of the Atlantic.[19]

The pear was also cultivated by the Romans, who ate the fruits raw or cooked, just like apples.[20] Pliny's Natural History recommended stewing them with honey and noted three dozen varieties. The Roman cookbook De re coquinaria has a recipe for a spiced, stewed-pear patina, or soufflé.[21] Romans also introduced the fruit to Britain.[22]

Pyrus nivalis, which has white down on the undersurface of the leaves, is chiefly used in Europe in the manufacture of perry (see also cider).[19][23][24] Other small-fruited pears, distinguished by their early ripening and globose fruit, may be referred to as P. cordata, a species found wild in southwestern Europe.[25][26][27]

The genus is thought to have originated in present-day Western China[28] in the foothills of the Tian Shan, a mountain range of Central Asia, and to have spread to the north and south along mountain chains, evolving into a diverse group of over 20 widely recognized primary species.[9] The enormous number of varieties of the cultivated European pear (Pyrus communis subsp. communis), are likely derived from one or two wild subspecies (P. c. subsp. pyraster and P. c. subsp. caucasica), widely distributed throughout Europe, and sometimes forming part of the natural vegetation of the forests.[5][8] Court accounts of Henry III of England record pears shipped from La Rochelle-Normande and presented to the king by the sheriffs of the City of London.[29] The French names of pears grown in English medieval gardens suggest that their reputation, at the least, was French; a favoured variety in the accounts was named for Saint Rieul of Senlis, Bishop of Senlis in northern France.[30]

Asian species with medium to large edible fruit include P. pyrifolia, P. ussuriensis, P. × bretschneideri, and P. × sinkiangensis.[8] Small-fruited species, such as Pyrus calleryana, may be used as rootstocks for the cultivated forms.[5][31]

Major species

[edit]

|

Cultivation

[edit]

According to Pear Bureau Northwest, about 3,000 known varieties of pears are grown worldwide.[32] The pear is normally propagated by grafting a selected variety onto a rootstock, which may be of a pear or quince variety. Quince rootstocks produce smaller trees, which is often desirable in commercial orchards or domestic gardens. For new varieties the flowers can be cross-bred to preserve or combine desirable traits. The fruit of the pear is produced on spurs, which appear on shoots more than one year old.[33]

There are four species which are primarily grown for edible fruit production: the European pear Pyrus communis subsp. communis cultivated mainly in Europe and North America, the Chinese white pear (bai li) Pyrus × bretschneideri, the Chinese pear Pyrus ussuriensis, and the Nashi pear Pyrus pyrifolia (also known as Asian pear or apple pear), which are grown mainly in eastern Asia.[5] There are thousands of cultivars of these three species.[32] A species grown in western China, P. sinkiangensis, and P. pashia, grown in southern China and south Asia, are also produced to a lesser degree.[5][8]

Other species are used as rootstocks for European and Asian pears and as ornamental trees.[5][31] Pear wood is close-grained and has been used as a specialized timber for fine furniture and making the blocks for woodcuts.[34][35] The Manchurian or Ussurian Pear, Pyrus ussuriensis (which produces unpalatable fruit primarily used for canning) has been crossed with Pyrus communis to breed hardier pear cultivars.[36] The Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana 'Bradford') is widespread as an ornamental tree in North America, where it has become invasive in regions.[37][38][39] It is also used as a blight-resistant rootstock for Pyrus communis fruit orchards.[36][37] The Willow-leaved pear (Pyrus salicifolia) is grown for its silvery leaves, flowers, and its "weeping" form.[5][40]

Cultivars

[edit]The following cultivars have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:[41]

- 'Beth'[42]

- 'Beurré Hardy'[43]

- 'Beurré Superfin'[44]

- 'Concorde'[45]

- 'Conference'[46]

- 'Doyenné du Comice'[47]

- 'Joséphine de Malines'[48]

The purely decorative cultivar P. salicifolia 'Pendula', with pendulous branches and silvery leaves, has also won the award.[49]

Harvest

[edit]Summer and autumn cultivars of Pyrus communis, being climacteric fruits, are gathered before they are fully ripe, while they are still green, but snap off when lifted.[8][50] Certain other pears, including Pyrus pyrifolia and P. × bretschneideri, have both climacteric and non-climacteric varieties.[5][51][52]

Diseases and pests

[edit]| Country | (Millions of tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 19.3 | |

| 0.58 | |

| 0.57 | |

| 0.55 | |

| 0.52 | |

| World | 26.3 |

| Source: FAOSTAT[53] | |

Production

[edit]In 2022, world production of pears was 26 million tonnes, led by China with 73% of the total (table).[53] About 48% of the Southern Hemisphere's pears are produced in the Patagonian valley of Río Negro in Argentina.[54]

Storage

[edit]Pears may be stored at room temperature until ripe.[55] Pears are ripe when the flesh around the stem gives to gentle pressure.[55] Ripe pears are optimally stored refrigerated, uncovered in a single layer, where they have a shelf life of 2 to 3 days.[55]

Pears ripen at room temperature. Ripening is accelerated by the gas ethylene.[56] If pears are placed next to bananas in a fruit bowl, the ethylene emitted by the banana causes the pears to ripen.[57] Refrigeration will slow further ripening. According to Pear Bureau Northwest, most varieties show little color change as they ripen (though the skin on Bartlett pears changes from green to yellow as they ripen).[58]

Uses

[edit]Cooking

[edit]

Pears are consumed fresh, canned, as juice, and dried. The juice can also be used in jellies and jams, usually in combination with other fruits, including berries. Fermented pear juice is called perry or pear cider and is made in a way that is similar to how cider is made from apples.[5][10] Perry can be distilled to produce an eau de vie de poire, a colorless, unsweetened fruit brandy.[59]

Pear purée is used to manufacture snack foods such as Fruit by the Foot and Fruit Roll-Ups.[60][61][62]

The culinary or cooking pear is green but dry and hard, and only edible after several hours of cooking. Two Dutch cultivars are Gieser Wildeman (a sweet variety) and Saint Remy (slightly sour).[63]

Timber

[edit]Pear wood is one of the preferred materials in the manufacture of high-quality woodwind instruments and furniture, and was used for making the carved blocks for woodcuts. It is also used for wood carving, and as a firewood to produce aromatic smoke for smoking meat or tobacco. Pear wood is valued for kitchen spoons, scoops and stirrers, as it does not contaminate food with color, flavor or smell, and resists warping and splintering despite repeated soaking and drying cycles. Lincoln[64] describes it as "a fairly tough, very stable wood... (used for) carving... brushbacks, umbrella handles, measuring instruments such as set squares and T-squares... recorders... violin and guitar fingerboards and piano keys... decorative veneering." Pearwood is the favored wood for architect's rulers because it does not warp. It is similar to the wood of its relative, the apple tree (Malus domestica) and used for many of the same purposes.[64]

Nutrition

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 239 kJ (57 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15.23 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 9.75 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 3.1 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.14 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.36 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 84 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[65] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[66] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Raw pear is 84% water, 15% carbohydrates and contains negligible protein and fat (table). In a 100 g (3+1⁄2 oz) reference amount, raw pear supplies 239 kilojoules (57 kilocalories) of food energy, a moderate amount of dietary fiber, and no micronutrients in significant amounts (table).

Research

[edit]A 2019 review found preliminary evidence for the potential of pear consumption to favorably affect cardiovascular health.[67]

Cultural references

[edit]Pears grow in the sublime orchard of Alcinous, in the Odyssey vii: "Therein grow trees, tall and luxuriant, pears and pomegranates and apple-trees with their bright fruit, and sweet figs, and luxuriant olives. Of these the fruit perishes not nor fails in winter or in summer, but lasts throughout the year."[68]

"A Partridge in a Pear Tree" is the first gift in the cumulative song "The Twelve Days of Christmas".[69]

The pear tree was an object of particular veneration (as was the walnut) in the tree worship of the Nakh peoples of the North Caucasus – see Vainakh mythology and see also Ingushetia – the best-known of the Vainakh peoples today being the Chechens of Chechnya. Pear and walnut trees were held to be the sacred abodes of beneficent spirits in pre-Islamic Chechen religion and, for this reason, it was forbidden to fell them.[70]

Gallery

[edit]-

Pears simmered in red wine

-

Pear in a bottle of pear eau de vie

-

Pear blossom in eastern Siberia

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "pear". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "pyriform, adj". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "pĭrus". A Latin Dictionary. Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022 – via the Perseus Project.

- ^ Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange. "PYRUS". Glossarium Mediae et Infimae Latinitatis. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022 – via Logeion.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bell, Richard L.; Itai, Akihiro (2011), Kole, Chittaranjan (ed.), "Pyrus", Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 147–177, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16057-8_8, ISBN 978-3-642-16056-1, retrieved 7 June 2024

- ^ Janick, Jules; Moore, James N., eds. (1996). Fruit breeding. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-12675-1.

- ^ a b "Pyrus communis - Plant Finder". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Quinet, Muriel; Wesel, Jean-Pierre (2019), Korban, Schuyler S. (ed.), "Botany and Taxonomy of Pear", The Pear Genome, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–33, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11048-2_1, ISBN 978-3-030-11048-2, retrieved 7 June 2024

- ^ a b Rubtsov, G. A. (July 1944). "Geographical Distribution of the Genus Pyrus and Trends and Factors in Its Evolution". The American Naturalist. 78 (777): 358–366. doi:10.1086/281206. ISSN 0003-0147.

- ^ a b c Hedrick, U.P.; Howe, G.H.; Taylor, O.M.; Frances, E.H.; Tukey, H.B. (1921). The Pears of New York. Albany: J. B. Lyon Co.

- ^ "Evergreen Pear - SelecTree: A Tree Selection Guide". selectree.calpoly.edu. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ Pear Fruit Facts Page Information. bouquetoffruits.com

- ^ "Pyrus in Flora of North America @ efloras.org". www.efloras.org. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ The New Werner Twentieth Century Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Standard Work of Reference in Art, Literature, Science, History, Geography, Commerce, Biography, Discovery and Invention. Werner Company. 1907. p. 456.

- ^ Nelson, John. "Spring blooming Asian pear looks much like an apple | Mystery Plant". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ Antolín, Ferran; Bleicher, Niels; Brombacher, Christoph; Kühn, Marlu; Steiner, Bigna L.; Jacomet, Stefanie (6 June 2016). "Quantitative approximation to large-seeded wild fruit use in a late Neolithic lake dwelling: New results from the case study of layer 13 of Parkhaus Opéra in Zürich (Central Switzerland)". Quaternary International. Archaeobotany of wild plant use: Approaches to the exploitation of wild plant resources in the past and its social implications. 404: 56–68. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.003. ISSN 1040-6182.

- ^ Clement, Charles R. (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 0415927463.

- ^ Ibn al-'Awwam, Yaḥyá (1864). Le livre de l'agriculture d'Ibn-al-Awam (kitab-al-felahah) (in French). Translated by J.-J. Clement-Mullet. Paris: A. Franck. pp. 240–242 (ch. 7 - Article 12). OCLC 780050566. (pp. 240–242 (Article XII)

- ^ a b de Candolle, Alphonse (1908). The Origin of Cultivated Plants: The International Scientific Series Volume XLVIII. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne (2009). A History of Food. John Wiley & Sons. p. 573. ISBN 978-1-4443-0514-2.

- ^ Grainger, Sally & Grocock, Christopher (2006). Apicius (with an introd. and an Engl. transl.). Blackawton, Totnes: Prospect Books. p. IV.2.35. ISBN 978-1-903018-13-2.

- ^ Lyle, Katie Letcher (2010) [2004]. The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants, Mushrooms, Fruits, and Nuts: How to Find, Identify, and Cook Them (2nd ed.). Guilford, CN: FalconGuides. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-59921-887-8. OCLC 560560606.

- ^ Kole, Chittaranjan; Kole, Chittaranjan (2011). Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding Resources Temperate Fruits. Biomedical and Life Sciences (Springer-11642). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg Springer e-books. ISBN 978-3-642-16057-8.

- ^ Itai, A. (2007), Kole, Chittaranjan (ed.), "Pear", Fruits and Nuts, vol. 4, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 157–170, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-34533-6_6, ISBN 978-3-540-34531-2, retrieved 8 June 2024

- ^ Aldasoro, J. J.; Aedo, C.; Garmendia, F. MuñOz (28 June 2008). "The genus Pyrus L. (Rosaceae) in south-west Europe and North Africa". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 121 (2): 143–158. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1996.tb00749.x.

- ^ AYDIN, ZÜBEYDE; DÖNMEZ, ALİ (1 January 2015). "Taxonomic and nomenclatural contributions to Pyrus L. (Rosaceae) from Turkey". Turkish Journal of Botany. 39 (5): 841–849. doi:10.3906/bot-1411-34. ISSN 1300-008X.

- ^ "Pyrus cordata | Plymouth pear Trees/RHS Gardening". www.rhs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Silva, G. J.; Souza, Tatiane Medeiros; Barbieri, Rosa Lía; Costa de Oliveira, Antonio (2014). "Origin, Domestication, and Dispersing of Pear ( Pyrus spp.)" (PDF). Advances in Agriculture. 2014: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2014/541097. ISSN 2356-654X.

- ^ Amherst, Alicia (1895). A History of Gardening in England by the Hon. Alicia (M.T.) Amherst ... B. Quaritch.

- ^ Cecil, Evelyn (2006). A History of Gardening in England. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 35 ff. ISBN 978-1-4286-3680-4.

- ^ a b "Rootstocks for Pear | WSU Tree Fruit | Washington State University". Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Pear Varieties". Usapears.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ RHS Fruit, Harry Baker, ISBN 1-85732-905-8, pp100-101.

- ^ "Pear | The Wood Database (Hardwood)". Archived from the original on 24 March 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Woodcut". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 8 June 2024. Archived from the original on 15 May 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ a b Bell, Richard L. (2019), Korban, Schuyler S. (ed.), "Genetics, Genomics, and Breeding for Fire Blight Resistance in Pear", The Pear Genome, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 243–264, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11048-2_13, ISBN 978-3-030-11047-5, retrieved 8 June 2024

- ^ a b Culley, Theresa M.; Hardiman, Nicole A. (1 December 2007). "The Beginning of a New Invasive Plant: A History of the Ornamental Callery Pear in the United States". BioScience. 57 (11): 956–964. doi:10.1641/b571108. ISSN 1525-3244.

- ^ Vincent, Michael A. (1 March 2005). "On the Spread and Current Distribution of Pyrus calleryana in the United States". Castanea. 70 (1): 20–31. doi:10.2179/0008-7475(2005)070[0020:OTSACD]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0008-7475.

- ^ Owen, Luke (27 March 2024). "Bradford Pear: An Invasive Pest". buncombe.ces.ncsu.edu. Archived from the original on 29 May 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "Pyrus salicifolia 'Pendula' - Plant Finder". www.missouribotanicalgarden.org. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ "AGM Plants" (PDF).

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Pyrus communis 'Beth' (D) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Pyrus communis 'Beurré Hardy'". Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Pyrus communis 'Beurré Superfin'". Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Pyrus communis 'Concorde' PBR (D) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Pyrus communis 'Conference' (D) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Pyrus communis 'Doyenné du Comice'". Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "RHS Plant Selector Pyrus communis 'Joséphine de Malines' (D) AGM / RHS Gardening". Apps.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "RHS Plantfinder - Pyrus salicifolia 'Pendula'". Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Marini, Richard P. (2009). "Growing Pears in Virginia". Virginia Cooperative Extension. Publication 422-017. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024.

- ^ Itai, Akihiro; Fujita, Naoko (February 2008). "Identification of Climacteric and Nonclimacteric Phenotypes of Asian Pear Cultivars by CAPS Analysis of 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate Synthase Genes". HortScience. 43 (1): 119–121. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.43.1.119. ISSN 0018-5345.

- ^ Korban, Schuyler S., ed. (2019). The pear genome. Compendium of plant genomes. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-11047-5.

- ^ a b "Production of pears in 2022, Crops/Regions/World Regions/Production Quantity/Year by picklists". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division. 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Las peras de Río Negro convierten al país en el segundo exportador a nivel mundial". Registro Civil (in Spanish). 31 January 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Canadian Produce Marketing Association > Home Storage Guide for Fresh Fruits & Vegetables. cpma.ca

- ^ Himmelblau, David M.; Riggs, James B. (2022). Basic principles and calculations in chemical engineering. International series in the physical and chemical engineering sciences (Ninth ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-732717-1.

- ^ Scott, Judy & Sugar, David (2011). "Pears can be ripened to perfection". extension.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Pear Bureau Northwest". Usapears.org. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Stewart, Amy (2013). The drunken botanist: the plants that create the world's great drinks. A New York Times bestseller. Chapel Hill, N.C: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. ISBN 978-1-61620-046-6.

- ^ "Global and Japan Pear Puree Market Analysis 2022: Industry Size, Share, Emerging Trends, Growth Opportunities And Forecast To 2028". www.stratagemmarketinsights.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "EWG's Food Scores: Fruit by the Foot Fruit Flavored Snacks, Strawberry, Strawberry". www.ewg.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "EWG's Food Scores: Fruit Roll Ups Blue Raspberry, Berry Punch Fruit Flavored Sour Snacks, Blue Raspberry, Berry Punch". www.ewg.org. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Koene, A. (2005). Food Shopper's Guide to Holland: A Comprehensive Review of the Finest Local and International Food Products in the Dutch Marketplace. Eburon Uitgeverij B.V. p. 79. ISBN 978-90-5972-092-3.

- ^ a b Lincoln, William (1986). World Woods in Color. Fresno, California, USA: Linden Publishing Co. Inc. pp. 33, 207. ISBN 0-941936-20-1.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Gayer BA, Avendano EE, Edelson E, et al. (2019). "Effects of Intake of Apples, Pears, or Their Products on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Current Developments in Nutrition. 3 (10): nzz109. doi:10.1093/cdn/nzz109. PMC 6813372. PMID 31667463.

- ^ Homer (1975) [Composed 8th century BCE]. The Odyssey of Homer. Translated by Lattimore, Richmond. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060904791.

- ^ Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. "The twelve days of Christmas". Broadside Ballads Online. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ The Chechens: A Handbook by Jaimoukha, Amjad. Published by Psychology Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-32328-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Joan Morgan (2015). The Book of Pears: The Definitive History and Guide to Over 500 Varieties. Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1603586665.