Palu

Palu | |

|---|---|

| City of Palu Kota Palu | |

Clockwise from the top: Palu seen at night, Palu Nusantara Gong of Peace, Nosarara Nosabatutu Peace Monument, Palontoan flyover, and Floating Mosque of Palu | |

| Motto(s): Maliu Ntuvu (Uniting all existing elements and potential) | |

Interactive map of Palu | |

| Coordinates: 0°53′42″S 119°51′34″E / 0.89500°S 119.85944°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Sulawesi |

| Province | |

| Incorporated | 1 July 1978 |

| City Status | 22 July 1994 |

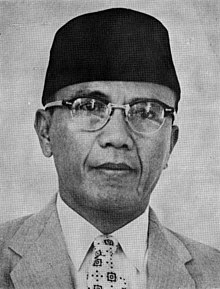

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hadianto Rasyid |

| • Vice Mayor | Reny A. Lamadjido |

| Area | |

• Total | 395.06 km2 (152.53 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 118 m (387 ft) |

| Population (mid 2023 estimate) | |

• Total | 387,493 |

| • Density | 980/km2 (2,500/sq mi) |

| [1] | |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (Indonesia Central Time) |

| Area code | (+62) 451 |

| HDI (2022) | |

| Website | www |

Palu, officially known as the City of Palu (Indonesian: Kota Palu), is the capital and largest city of Central Sulawesi Province in Indonesia. Palu is located on the northwestern coast of Sulawesi and borders Donggala Regency to the north and west, Parigi Moutong Regency to the east, and Sigi Regency to the south. The city boundaries encompass a land area of 395.06 km2 (152.53 sq mi). According to the 2020 Indonesian census, Palu had a population of 373,218, making it the third-most populous city on the island after Makassar and Manado; the official estimate as at mid 2023 was 387,493 - comprising 194,340 males and 193,150 females.[2] Palu is the center of finance, government, and education in Central Sulawesi, as well as one of several major cities on the island. The city hosts the province's main port, its biggest airport, and most of its public universities.

Palu is located in Palu Bay; it was initially a small agricultural town until it was selected to become the capital of the newly created province of Central Sulawesi in 1953. Palu is sited on the Palu-Koro Fault and is frequently struck by earthquakes, such as the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake. According to Indonesia's National Disaster Management Agency, the 2018 earthquake caused "the largest natural soil liquefaction phenomenon in the world".[3] Much of the city's infrastructure was destroyed and large swathes of land were rendered uninhabitable,[4] prompting the local government to plan to relocate the city to a safer location instead of rebuilding in the same place.[5]

History

[edit]Palu was founded as an agricultural town and had been less significant than the then-bigger town of Donggala around 35 km (22 miles) away.[6] The creation of Palu was initiated by people from several villages around Ulayo Mountain. There are different accounts of the origin of the city's name; according to one explanation, it came from the word topalu'e, which means "raised land"; another version states it was derived from the word volo, the name of local bamboo plants.[7]

Early history

[edit]The early history of Palu and its surroundings can be divided into the Tomalanggai Era, the Tomanuru Era, and the Independent Era.[6]

During the Tomalanggai Ere which lasted until the founding of Kaili Kingdom in the 15th century,[8] most of the inhabitants were hunter-gatherers and relatively violent. Due to scarce resources, many tribal groups waged war against each other, and the losing group would need to settle with the winner and work for them. The leaders of these early settlers were called Tomalanggai. The power structure was not yet formalized; the Tomalanggai were essentially absolute rulers with no limits of power, which caused frequent wars and rebellions.[6] The following Tomanuru Era, in which power was consolidated and village structures became formalized, several reforms were made and life was relatively peaceful. According to local legend, during this era, villages were ruled by descendants of gods from heaven. It was said a Tomalanggai one day wanted golden bamboos, which grew around the region, for his water container and commanded his troops to chop all of them. After the bamboo were chopped down, a storm suddenly came but soon stopped; after the storm, a beautiful women appeared where the bamboo was. The Tomalanggai took her to his village and married her, and their descendant was wiser and stronger than his father. The name of the period roughly means "the one that brings blessing". This period lasted until about the 16th century. During this era, an aristocratic class called the madika appeared within Kaili society.[6]

After the Tomanuru Era, the region experienced another historical period Indonesian historians called "zaman Merdeka" or the Independent Era. During this time, kingdoms in the region started to have trade contacts with the outside world and several signs of an early form of democratic government. Kingdoms in the region were no longer led by single power entity; power was devolved to several representative bodies and councils. The power structure was divided into magau (kings) who lead the kingdoms, madika were nobles who led districts, and kapala who led villages. Kingdoms had structures such as patanggota (four officials), pitunggota (seven officials), and walunggota (nine officials), referring to the number of ministries beside the king who managed the kingdom. Kingdoms around the region also developed military structures with full-time officers and commanders. This era lasted roughly until the arrival of the Dutch in the region.[6]

Kingdoms in the region during this period included Bangga Kingdom and Pakawa Kingdom, which were located around 30 km (19 miles) from the modern-day location of the city. Other kingdoms in the region, particularly in the Palu Valley, were Palu Kingdom, Tawaeli, Bora, and Sigi. Bangga and Sigi Kingdoms were among the biggest and most powerful, acting as regional powers.[6]

Colonial era

[edit]

Contact with Europeans, particularly Portuguese, occurred since the late 16th century, mainly for trading and rights to use ports. Portuguese influence is evident in several communities of Kaili people, particularly in the region that used to be under the Kulawi Kingdom, around 80 km (50 miles) from Palu, where dress that resembles that of the Portuguese is worn.[6] Contact with the Dutch began in the 19th century when the Portuguese influence in the region had waned. The first kingdom to sign a contract with the Dutch was the Sigi Kingdom, which signed a Large Kontrack in 1863 and Karte Verklaring in 1917. The kingdom of Banawa also signed Large Kontrack in 1888 and Kartte Verklaring in 1904. Other smaller kingdoms soon followed by signing the same contracts and agreements. Between 1863 and 1908, practically all kingdoms in the region were under the influence of the Dutch and were soon incorporated into the Dutch East Indies.[6] There was some local resistance, such as the Donggala War in 1902, which was led by King Tombolotutu; the Sigi War between 1905 and 1908 led by King Toi Dompu; and the Kulawi War between 1904 and 1908. The native kingdoms were mostly defeated in the war and there would be no further significant resistance from the natives until 1942.[6]

World War II and National Revolution

[edit]

In 1942, influenced by World War II and the rising Indonesian nationalism movement, an uprising referred to as Merah Putih Movement (lit: Red and White Movement) appeared in the region. The uprising in this region started on 25 January 1942 when a local Dutch colonial police chief was killed and several officials were taken hostage by the movement. In Central Sulawesi, the movement was closely connected to the one organized by Nani Wartabone in Gorontalo about the same time. The movement controlled the region of the former Kulawi Kingdom and was supported by ex-nobles from the region. The Kingdom of Kulawi was revived and royal troops were mobilized to support the nationalist cause. The movement's stronghold was in Momi Mountain, across the Miu River. As the result of the movement, Toi Torengke the King of Kulawi was arrested. On 1 February 1942, the movement raised the Indonesian flag at Tolitoli and played Indonesia Raya, resulting in an assault by the Dutch military and the killing of several nationalist figures in the region. The movement soon spread to other regions such as Luwuk and Poso. The Red and White Movement pledged its allegiance to the National Government, a provisional Indonesian government set up by Nani Wartabone in Gorontalo. Following the Dutch East Indies' conquest by the Empire of Japan, the Red and White Movement collapsed as result of the arrest of Nani Wartabone by Japanese forces. The nationalist movement in Sulawesi was suppressed and seen with suspicion by Imperial Japanese Navy, which occupied the region, unlike other regions such as Java and Sumatra, which were under control of the Japanese army.[9][6][10]

Following the surrender of Japan and Proclamation of Indonesian Independence in Jakarta, a paramilitary organization named Laskar Tanjumbulu was formed by surviving fighters of the previous Merah Putih Movement. The paramilitaries took over several Japanese military facilities and weapons while distributing news about Indonesian Independence. The remaining Japanese officials transferred governance to several native kings in the region including Palu before leaving. Some of these kings later supported an Indonesian republic and created difficulties for the returning Dutch administration. The King of Palu and Parigi accepted the return of the Dutch administration, which landed in Palu in late 1945. On 31 January 1946, a widespread repression of the nationalist movement occurred. The region, including the city, later became part of State of East Indonesia until the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference, at which the Dutch acknowledged Indonesian sovereignty and the State of East Indonesia was disbanded one year later.[6] In Palu, the dissolution of the State of East Indonesia and return to a unitary republic occurred in a building today called Gedung Juang.[11][12][6]

Modern history

[edit]

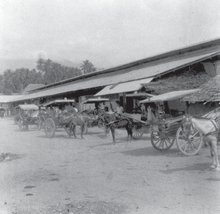

While the city had a Dutch official seat during the colonial era, Palu was still by this time a small agriculture town with little significance, while Central Sulawesi region's economic and political activities were centered around Poso and Donggala.[6] The center of economic activity in the region shifted when the larger Pantoloan Port was built in Palu Bay, and an airport which today become Mutiara SIS Al-Jufrie Airport. The construction of Pantoloan Port which competed with the older Donggala Port initially were met with objections especially from ship owners and officials in Donggala.[6] Palu's population grew dramatically in the 1950s and 60s, while Donggala's population growth stagnated around the 1960s. In 1951, Poso Regency was founded with its capital in Poso and Palu Regency with its capital in Palu. This was met with opposition and conflict between residents of Palu and Donggala, as the Donggala residents believed it would further limit the town's development.[6] To avoid conflict, on 14 September 1951, a motion was sent to Sulawesi governor to rename Palu Regency to Donggala Regency while keeping the capital in Palu as a compromise.[6] Palu continued to outgrow Donggala, and the creation of Palu Administrative City and subsequent creation of Central Sulawesi province in 1964 with Palu as its capital further distanced Donggala from its past status.[6] The province was established on 12 April 1964 due to demand from student groups for its creation to represent the region.[6] The city gained administrative status in 1978 and kotamadya in 1994.[13]

On 28 September 2018, the city was hit by a devastating earthquake and tsunami. The city itself also experienced severe soil liquefaction.[14][15] The liquefaction was the biggest in the world and caused massive destruction in parts of the city.[3] The land where liquefaction happened is currently uninhabitable.[4] In the aftermath of the disaster, several calls by politicians were made to relocate the capital city of Central Sulawesi away from Palu due to its vulnerability to earthquakes.[16][17] The plan for city-wide relocation was made by the city government, dubbed Kota Palu Baru (New Palu City) was predicted to cost between five and six trillion of Rupiah.[5] Affected areas of the earthquake are still being rebuilt, with progress only reaching 45% in May 2022 and predicted to last until the end of 2023.[18] Ambiguity of land status outside city boundaries supposedly used for new housing for victims of the earthquake in particular hampered the relocation progress, and as many as 6,000 people still live in temporary housing in 2022.[19]

Geography

[edit]The city of Palu is located in the Palu basin, close to Palu Bay, and lies directly on the Palu-Koro Fault. The basin is mostly composed of alluvial deposits of clay, silt, and sand, which were deposited by the flow of the Palu River from land above the valley. Alluvial sediments around the city are not consolidated and relatively young. The basement rock has been dated to the Cretaceous period. Below the layers of deposits, the rock in the region is mostly tertiary granite and granodiorite. The sediments are between 25 and 125 meters (82 and 410 ft) depending on the location; sediments in the northern part of the city are thicker than those in the south because they are closer to the river's estuary.[20]

The Palu–Koro Fault runs for around 300 km (190 miles) through Palu Bay, cutting into the middle of the city, and is connected to a subduction zone in northern Sulawesi. The abundance of relatively weak sediments below the city was among the causes of massive soil liquefaction and landslides that occurred during the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake; the soil below the city was not consolidated enough.[20][21]

Climate

[edit]Palu has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af), although it is relatively dry due to the strong rain shadow of the surrounding mountains.[22]

| Climate data for Palu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 38 (100) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

35 (95) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

38 (100) |

37 (99) |

37 (99) |

38 (100) |

38 (100) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.6 (79.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.9 (80.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 101 (4.0) |

88 (3.5) |

90 (3.5) |

102 (4.0) |

130 (5.1) |

157 (6.2) |

158 (6.2) |

147 (5.8) |

164 (6.5) |

109 (4.3) |

110 (4.3) |

76 (3.0) |

1,432 (56.4) |

| Average rainy days | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 106 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 76.5 | 75.5 | 76 | 75.5 | 76.5 | 77 | 74 | 74.5 | 73 | 73 | 74.5 | 75 |

| Source 1: weatherbase[23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: climate-data[22] | |||||||||||||

Governance

[edit]Administrative division

[edit]At the time of the 2010 Indonesian census, Palu was divided into four districts (kecamatan); in 2011 these were re-organized into a new division of eight districts. These are tabulated below with their areas and their population at the 2010 census[24] and the 2020 census,[25] together with the official estimates as of mid 2023.[26] The table also includes the number of urban villages (kelurahan) in each district.

| Kode Wilayah |

Name of District (kecamatan) |

Area in km2 | Pop'n census 2010 |

Pop'n census 2020 |

Pop'n estimate mid 2023 |

No. of kelurahan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72.71.02 | Palu Barat (West Palu) |

8.28 | 98,739 | 46,435 | 47,118 | 6 |

| 72.71.06 | Tatanga | 14.95 | [a] | 52,580 | 55,093 | 6 |

| 72.71.05 | Ulujadi | 40.25 | [a] | 35,055 | 36,796 | 6 |

| 72.71.03 | Palu Selatan (South Palu) |

27.38 | 122,752 | 72,059 | 74,481 | 5 |

| 72.71.01 | Palu Timur (East Palu) |

7.71 | 75,967 | 43,318 | 44,021 | 5 |

| 72.71.08 | Mantikulore | 206.80 | [a] | 76,745 | 81,012 | 8 |

| 72.71.04 | Palu Utara (North Palu) |

29.94 | 39,074 | 24,458 | 25,431 | 5 |

| 72.71.07 | Tawaeli | 59.75 | [a] | 22,568 | 23,521 | 5 |

| Totals | 395.06 | 336,532 | 373,218 | 387,493 | 46 |

Local government

[edit]As is the case with all Indonesian cities, the local government of Palu is a second-level administrative division run by a mayor and vice mayor, and the city parliament; it is of equivalent tier as a regency.[27] Executive power lies in the mayor and vice mayor, and legislation duties are carried by local parliament. The mayor, vice mayor, and parliament members are democratically elected by residents of the city.[28] Heads of districts are directly appointed by the city mayor on recommendations from the city secretary.[29][30]

Politics

[edit]Palu People's Representative Council Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Palu | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

New session started | 9 September 2019 |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 35 |

Political groups |

Nasdem Party (4)

Perindo Party (1)

Hanura (4)

Demokrat (3)

Golkar (5)

Gerindra (6)

PAN (2)

PKB (3)

PKS (4)

[31] |

| Elections | |

| Open list | |

Palu is part of 1st Central Sulawesi electoral district, which consists of only the city itself, and has 6 representatives of 45 seats in the provincial parliament. The city is divided into four electoral districts. The city parliament has 35 seats. As the capital of Central Sulawesi, Palu is the location of the governor's office and the seat of the provincial parliament. The table below shows the division of electoral districts in the city and the number of representatives they send to city parliament as of 2019.[32][33]

| Electoral district | Districts | Seats |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Palu City | Mantikulore, East Palu | 11 |

| 2nd Palu City | Tawaeli, North Palu | 4 |

| 3rd Palu City | South Palu, Tatanga | 12 |

| 4th Palu City | West Palu, Ulujadi | 8 |

| Total | 35 | |

Economy

[edit]Palu's gross regional product (GRP) was valued at 24.175 trillion Rupiah in 2020. The city's economic growth was 5.79% in 2019 but later fell to -4.54% in 2020. This contraction on city's economic growth was caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the restrictions that later followed.[34] In 2021, Palu's economic growth again became positive at 5.97%.[35]

Economic activities in Palu are diverse. The largest sectors in the city, according to its contribution to GRP, were construction (19.41%), administration activities and social security (14.74%), and the information and communication sector (10.20%) in 2020.[34] Other sectors present in the city are trade (9.70%), education (7.90%), and manufacturing (6.57%).[34]

Agriculture

[edit]Palu was historically an agricultural town. In 1947, it was estimated 97% of the city's residents were working in agriculture. The biggest agriculture product between the 1940s to 1950s was copra with an output of up to 718,000 tons in 1947.[6]

Despite a large decline, agriculture is still present in Palu. In 2021, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries accounted for 3.83% of the city's GRP. While importance of agriculture to the city's economy is insignificant compared to that in the 1940s and 1950s, agricultural output in terms of tonnage currently is significantly bigger, with rice production as high as 1,492 tons in 2018 compared to 15 tons in 1947; and maize with 3,255 tons in 2021 compared to 10 tons in 1947.[35][6] Other agriculture products from the city include 296.8 tons of groundnuts, 616.6 tons of cassava, 145 tons of chili, 325.4 tons of shallot, 438.5 tons of cayenne pepper, 13.34 tons of spinach, 854.8 tons of tomato, and 49.3 tons of water spinach.[35] Tawaeli district has sizeable herb plants output with 1.9 tons of ginger, 2.6 tons of turmeric, and 3.2 tons of galangal. The city also produces 257.4 tons of mango, 178.8 tons of jackfruit, and 366.3 tons of banana.[35]

The most-populous livestock in the city is chicken with recorded population of 3,449,629 in 2021. The city's fisheries industry includes seafood catches and freshwater aquaculture. The aquaculture industry in the city in 2021 was valued at around 4 billion rupiah, while catches from sea was valued at 45 billion rupiah.[35]

Manufacturing and industry

[edit]

Palu's manufacturing and processing industry consisted of 1,860 registered large-scale companies that employ 9,339 people in 2020. There were also 1,789 registered smaller-to-medium-sized companies in this sector, which employed 6,140 people in the same year.[34] The city is the location of Palu Special Economic Zone, which hosts companies focusing on processing of agricultural and mineral products.[36] In Palu, raw materials used for industries mostly came from outside of the city; these include nickel from Morowali Regency, materials for asphalt from Buton Regency, and cocoa beans from plantations across the province, of which Central Sulawesi is one of the largest producers in the country.[37][38]

Hotels and tourism

[edit]As the capital of Central Sulawesi, Palu has a significant hotel sector. In 2020, there were 116 registered hotels in the city according to Statistics Indonesia. Tourism, however, has been declining; the numbers of foreign and domestic tourists visiting the city decreased from 291,930 domestic visitors and 3,709 foreign visitors in 2017 to 156,733 domestic visitors and 1,110 foreign visitors in 2019. This number further decreased to 70,562 domestic visitors and 194 foreign visitors in 2020.[34] Tourism and the hotel industry in Palu has declined since 2018 due to that year's earthquake and tsunami[39] and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.[40] Although there were signs of recovery in 2019 in the aftermath of the earthquake,[41] the pandemic delayed further recovery of hotel industry until late 2021.[42][43]

The city had 128 registered restaurants in 2021, although the number would be significantly higher if unregistered restaurants are included.[35]

Finance and banking

[edit]Palu is the financial center of Central Sulawesi. Bank Sulteng (Central Sulawesi Bank), the regional development bank of the province, is headquartered in the city.[44] The city has 215 registered cooperatives with combined assets of around 22 billion rupiah. The trading and wholesale sector, totaling almost 4 billion rupiah worth of credits, is the largest sector that received credit from banks in the city. In total, Palu's economy has 16 billion rupiah worth of credits from banks. The city has 27 branches of national and international banks, and several municipally-owned people's credit banks (BPR).[35] The city has several insurance companies and is the location of the Central Sulawesi branch of Indonesia Stock Exchange.[35]

Demographics

[edit]In 2020, Palu's population was 373,218 with a population density of 944.71 per square kilometer. The sex ratio in the city was 100, meaning the ratio of males to females is relatively equal and stable. The number of people aged 15 and older, who are considered part of workforce by Statistics Indonesia, was 201,083. As with other regions in Indonesia, the populace of Palu is relatively young; most population in 2020 were between 20 and 30 years old. The population of the city's Mantikulore district grew 1.77% growth between 2010 and 2020—the fastest growth in the city—while the slowest was West Palu with 0.43% population growth. The poverty rate in 2021 was 7.17% of the population and the unemployment rate was 7.61%.[35]

The region's native Kaili people form the majority of the city's population, and there are significant populations of Bugis and Minahasan migrants from neighboring provinces, who mostly work as traders and government workers. There are small populations of Chinese Indonesians and Arab Indonesians, as well as other ethnicities from all over Indonesia such as Batak, Javanese, Malays, and Minangkabau. As a capital city and an economic center, Palu attracts migrants looking for economic opportunities from all around Indonesia.[6]

Most of the city's population are Muslims; the region was converted to Islam in the 17th century. The population of Christians are mostly migrants from other parts of Indonesia but there is also a local Christian population due to missionary activities in the region that started in 1888. Other minorities exist are Buddhists and Hindus from other parts of Indonesia.[6] As of 2021[update], Palu has 504 mosques, 108 Protestant churches, 2 Catholic churches, 4 Balinese temple, and 4 Vihāra.[45]

The relationship between the Kaili and Minahasan populations was tense during its early days partly due to religious differences between the mostly-Muslim Kaili and the mostly-Christian Minahasan; and because the Minahasan, who were usually government workers during the colonial era and the early days of Indonesian republic, were generally considered financially more capable.[6] There was also brief tension between Bugis and Kaili people due to perceived economic differences, resulting in riots at traditional market in 1992 and 2004.[46][47]

Education

[edit]

As of 2020[update], Palu has 171 kindergartens, 190 elementary schools, 73 junior high schools, and 39 senior high schools. There were also 26 vocational high schools in the city in the same year. According to Statistics Indonesia, there are 13 universities and higher-education institutions in the city as of 2021[update].[48]

The city's most prominent university is Tadulako University, which is the main public university of Central Sulawesi. It has B accreditation and more than 40,000 students registered according to Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology.[49] Datokarama Islamic State University[50] was previously named State Islamic Institute of Datokarama Palu before being upgraded into university status on 8 July 2021.[50] Public colleges in the city include Kemenkes Health Polytechnic owned by Ministry of Health.[51] The city also hosts private universities and colleges such as Alkhairaat University, Muhammadiyah Palu University, Palu Theological College, and Palu Polytechnic.[52]

The city also hosts a public library that is managed by the provincial government.[53][54] Palu's literacy rate is relatively high at 99.60% for people between 15 and 19 years old, and 99.84% on average in the wider city population.[48]

Healthcare

[edit]

As of 2020[update], Palu has 13 hospitals—including three maternity hospitals—as well as 17 polyclinics, 39 puskesmas, and 35 registered pharmacies.[48]

One of the main public hospitals in the city is Undata Regional Hospital, which is managed by the government of Central Sulawesi province and is classified as B-class under government requirements for facilities and services rendered. It is also the main referral hospital for the province.[55][56][57] Other public hospitals in the city are Anutapura Palu Regional Hospital, Palu Wirabuana Hospital, Bhayangkara Hospital, and Madani Regional Hospital.[58][59][60] There are also private hospitals in the city such as Woodward Hospital, Budi Agung Hospital, and Sis Aljufri Hospital.[61][48]

The city also has 227 healthcare posts and 28 registered medical clinics, as of 2020.[48]

Culture and entertainment

[edit]Monuments

[edit]

Palu has a number of tourist sites and recreational places. Among them is Nosarara Nosabatutu Peace Monument, which contains a three-story building and is located adjacent to Nusantara Gong of Peace. The building's name is from a Kaili language phrase that means "we are siblings, we are united". The monument was built to commemorate the Poso riots, a communal conflict between Christians and Muslims in neighboring Poso Regency.[62] The monument functions as a museum containing messages about the importance of peace from different religions, and portraits and biographies of several figures advocating for peace, and displays several traditional crafts from several Indonesian cultures. The site is a popular with city residents because there are several cafes and an urban park nearby.[63] A site nearby the monument is used as an evacuation site in an event of a tsunami.[64] Nusantara Gong of Peace located in the site weights 180 kilograms (400 lb) and has a diameter of two meters (6.6 ft). The gong contains symbols of the five religions that were recognized in Indonesia at its construction, as well as the coats of arms of the then-33 provinces, and 444 regencies and cities in Indonesia.[63][64]

Other sites

[edit]

Other popular sites in the city include Citraland Palu, an amusement park which contains a Ferris wheel, urban parks, bumper cars, as well as cafes and shops around the area.[65][66] Palu Museum is focused on the history of Central Sulawesi; Sou Raja is a former palace of a local kingdom; and natural attractions include Talise Beach, Pantoloan Beach, and Kaombana Urban Forest.[67] The city also has several shopping malls.[68][69][70]

Transportation

[edit]

Palu has 851.6 km (529.2 miles) of road, from which 842.2 km (523.3 miles) are paved with asphalt. The city's main container port is Pantoloan Port, which is the main port of Central Sulawesi and the busiest in the province.[71] Pantoloan Port is used for direct exports from Sulawesi.[72] There are also smaller ports in the city such as Wani Port.[73]

Palu is served by Mutiara SIS Al-Jufrie Airport, which is the province's largest airport, and one of two airports in the province that can handle large aircraft such as the Boeing 737, the other being Syukuran Aminuddin Amir Airport in Banggai Regency.[74] It served around 1.2 million people in 2019 and handled around six million tons of cargo.[45] Pelni operates ship routes to Eastern Indonesia, Balikpapan, and Surabaya.[75]

Perum DAMRI, a state-owned bus company, served several bus route to and from Palu. Many routes were closed due to financial problems the company branch in the city experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and Russian invasion of Ukraine; as of 2022[update], the company branch operates 14 long-distance bus routes.[76] Many private bus companies serve the city, notably the route to Makassar.[77][78]

Share taxis known as angkot used to be a prominent means of public transport Palu but online ride-hailing services such as Gojek and Grab out-competed angkot. As of 2021, only 46 angkot vehicles remained operational compared to 400 in 2017.[79][80] COVID-19 pandemic, Russian invasion of Ukraine and earthquake disaster in 2018 also affected angkot business.[79] The city also has rickshaws; in June 2022, the city's mayor passed a regulation ordering all manual rickshaws in the city to be converted into auto rickshaws. The conversion is expected to finish in 2024.[81]

In the city center around Vatulemo Square and along Moh. Yamin Street, car-free days are held every weekend from 06:00 to 10:00 am.[82][83]

Media

[edit]Several mass media companies are based in Palu. In 2021, Statistics Indonesia noted there were 82 online newspapers operating in the city.[45] Prominent newspapers in the city include SultengRaya, Tribun Palu, and the media wing of Alkhairaat.[84] The city also has local television channels such as Palu TV,[85] a state-owned television station TVRI for Central Sulawesi province, and radio stations that are part of Radio Republik Indonesia.[86][87]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2024.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2024.

- ^ a b "BNPB Ungkap Tiga Bencana Indonesia Sebagai Fenomena Langka". CNN Indonesia. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Likuifaksi Palu Terbesar di Dunia" (in Indonesian). 12 October 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Dipindahkan, Ini Tiga Alternatif Lokasi Kota Palu Baru" (in Indonesian). 16 October 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Mamar, Sulaiman (1984–1985). Sejarah sosial daerah Sulawesi Tengah (wajah kota Donggala dan Palu). Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Direktorat Sejarah dan Nilai Tradisional, Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Sejarah Nasional. OCLC 15864232.

- ^ Putong, Ady (2 October 2018). "Kota Palu Dan Misteri Topalu'e yang Berarti Tanah Terangkat". Barta1.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ^ Septiwiharti, Dwi (4 August 2020). "Budaya Sintuvu Masyarakat Kaili di Sulawesi Tengah [The Sintuvu Culture of the Kaili People in Central Sulawesi]". Naditira Widya (in Indonesian). 14 (1): 47–64. doi:10.24832/nw.v14i1.419. ISSN 2548-4125.

- ^ Elson, Robert Edward (2009). The Idea of Indonesia (in Indonesian). Penerbit Serambi. ISBN 978-979-024-105-3. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ Kahin (1952), p. 355

- ^ "Gedung Juang Saksi Bisu Kemerdekaan di Sulawesi Tengah". KOMPAS.tv (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Putri, Arum Sutrisni, ed. (12 March 2020). "Kembali ke Negara Kesatuan Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Pemerintah Kota Palu. (2009). Palu Kota Dua Wajah. Palu: CACDS.

- ^ Safitri, Eva. "BNPB: Tinggi Tsunami Capai 5 Meter di Palu". detiknews (in Indonesian). Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Putra, Nanda Perdana (29 September 2018). "BNPB: Tsunami di Palu Tingginya Hampir 6 Meter". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Santoso, Bangun; Sari, Ria Rizki Nirmala (10 October 2018). "Rawan Gempa, Ibu Kota Sulteng Diusulkan Pindah dari Palu". suara.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Mashabi, Sania (9 October 2018). "DPR Usul Ibu Kota Sulawesi Tengah Dipindahkan dari Kota Palu". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ "Completed and 45% occupied, Ministry of PUPR Targets Huntap Development for Central Sulawesi to be Completed in December 2023".

- ^ Litha, Yoanes (7 January 2022). "Pembangunan Hunian Tetap Bagi Penyintas Bencana Alam di Sulteng Terhambat". VOA Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Investigasi_Awal_LongsorLikuifaksi_Geotechnical_Extreme_Events_Reconnaissance_Akibat_Gempa_Palu" (PDF).

- ^ Jalil, Abdul; Fathani, Teuku Faisal; Satyarno, Iman; Wilopo, Wahyu (24 August 2021). "Liquefaction in Palu: the cause of massive mudflows". Geoenvironmental Disasters. 8 (1): 21. Bibcode:2021GeoDi...8...21J. doi:10.1186/s40677-021-00194-y. ISSN 2197-8670. S2CID 237272220.

- ^ a b "CLIMATE TABLE // HISTORICAL WEATHER DATA". climate-data.org. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "PALU, INDONESIA". weatherbase.com. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2024.

- ^ "UU 22 1999" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "UU 8 2015" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ "PP No. 17 Tahun 2018 tentang Kecamatan [JDIH BPK RI]". peraturan.bpk.go.id. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Government Law No.19 1998

- ^ "Pelantikan 35 anggota DPRD Kota Palu". Antaranews.com. 9 September 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Keputusan KPU Nomor 289/PL.01.3-Kpt/06/KPU/IV/2018 tentang Penetapan Daerah Pemilihan dan Alokasi Kursi Anggota Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Provinsi dan Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Kabupaten/Kota di Wilayah Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah dalam Pemilihan Umum Tahun 2019" (PDF). KPU RI. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Keputusan KPU Nomor 289/PL.01.3-Kpt/06/KPU/IV/2018 tentang Penetapan Daerah Pemilihan dan Alokasi Kursi Anggota Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Provinsi dan Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Kabupaten/Kota di Wilayah Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah" (PDF). KPU RI. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Statistik Daerah Kota Palu 2021". palukota.bps.go.id. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Kota Palu Dalam Angka 2022". palukota.bps.go.id. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Jemali, Videlis (28 October 2020). "38 Perusahaan Berinvestasi di Kawasan Ekonomi Khusus Palu". kompas.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "KEK Palu". kek.go.id. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Downstream-Based Central Sulawesi Chocolate Development".

- ^ Sofia, Hanni (29 September 2018). "Kemenpar sebut lebih 200 kamar hotel di Palu terdampak gempa". Antara News. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ Susanto, Heri (18 April 2020). "Opsi Sulit Industri Hotel Sulteng Bertahan pada Masa Pandemi Covid-19". liputan6.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ Hajiji, Muhammad (24 September 2019). "Setahun bencana Sulteng, perhotelan di Palu mulai bangkit". Antara News. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ Murdaningsih, Dwi (2 September 2021). "Okupansi Hotel di Sulteng Mulai Naik". Republika Online (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Okupansi Hotel di Sulteng Mulai Meningkat". beritasatu.com (in Indonesian). 1 September 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Bank Sulteng". www.banksulteng.co.id. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Kota Palu Dalam Angka 2021". palukota.bps.go.id. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ AEPU, SITI HAJAR N. (5 July 2013). MODEL PENGELOLAAN KONFLIK DI PASAR INPRES MANONDA PALU KECAMATAN PALU BARAT SULAWESI TENGAH (masters thesis) (in Indonesian). Universitas Hasanuddin.

- ^ Lampe, Ilyas; Anriani, Haslinda B. (4 June 2016). "Stereotipe, Prasangka dan Dinamika Antaretnik". Jurnal Penelitian Pers Dan Komunikasi Pembangunan (in Indonesian). 20 (1): 19–32. doi:10.46426/jp2kp.v20i1.42 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2527-693X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e "Kota Palu Dalam Angka 2022". palukota.bps.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "PDDikti - Pangkalan Data Pendidikan Tinggi". pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Hajiji, Muhammad (19 July 2021). Jauhary, Andi (ed.). "IAIN Palu resmi alih status jadi Universitas Islam Negeri Datokarama". Antara News. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Poltekkes Kemenkes Palu". siskerma-bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "PDDikti - Pangkalan Data Pendidikan Tinggi". pddikti.kemdikbud.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Dinas Perpustakaan dan Kearsipan Daerah Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah - Jaringan Informasi Kearsipan Nasional". jikn.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Layanan Perpustakaan Daerah Sulteng Kembali Dibuka | KabarSelebes.id" (in Indonesian). 12 June 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Sejarah". RSUD Undata | Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah (in Indonesian). Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Informasi SDM Kesehatan Nasional". bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Tugas dan Fungsi". RSUD Undata | Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah (in Indonesian). Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Informasi SDM Kesehatan Nasional". bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Informasi SDM Kesehatan Nasional". bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Informasi SDM Kesehatan Nasional". bppsdmk.kemkes.go.id. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "RUMAH SAKIT – Pemerintah Kota Palu". Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Gong Perdamaian Nusantara Palu". www.djkn.kemenkeu.go.id. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b Muththalib, Abdullah (25 November 2020). "Tugu Perdamaian Nosarara Nosabatutu, Tujuan Bersantai Favorit Warga Palu". Celebes. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b Agmasari, Silvita (29 September 2018). Asdhiana, I Made (ed.). "Gong Perdamaian Palu, Mencegah Konflik dan Tempat Evakuasi Tsunami". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Suta, Ketut (16 May 2022). "Libur Akhir Pekan, Warga Padati Kawasan Citraland Palu". Tribunpalu.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Wahana Bermain Di Citraland, Alternatif Wisata Kota Kekinian". SultengRaya (in Indonesian). 29 December 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "10 Tempat Wisata di Palu Terbaru yang Lagi Hits". Senang Rekreasi. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "PUSAT PERBELANJAAN – Pemerintah Kota Palu". Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Salam, Mohamad (3 February 2022). "Wahana Human Claws Hadir di Palu Grand Mall, Berikut Tarif dan Syaratnya". Tribunpalu.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ RRI 2022, LPP. "PT CNE Percepat Pembangunan New Mall Tatura Palu". rri.co.id. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Pantoloan, Pelabuhan Indonesia-Pelabuhan. "Pelabuhan Indonesia - Pelabuhan Pantoloan | Shipsapp". shipsapp.co.id. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Gubernur Sulawesi Tengah Drs. H. Longki Djanggola, M.Si. Gowes dari Palu – Pantoloan untuk Melaksanakan Pelepasan Direct Export dari Terminal Peti Kemas Kelapa dan Kayu Olahan Ke Vietnam, Korea, China, Jepang dan Malaysia – Dinas Penanaman Modal dan Pelayanan Terpadu Satu Pintu Provinsi Sulawesi Tengah" (in Indonesian). 14 September 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Pasca Bencana, Rehabilitasi Pelabuhan Wani, Palu Dimulai". BISNISNEWS.id. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Malaha, Rolex, ed. (2 November 2017). "Sulteng terbanyak miliki bandar udara". Antara News Palu. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Omed, Kata (27 April 2022). "Jadwal Kapal Pelni Dari Pantoloan Palu Bulan Juni 2022 Dan Harga Tiketnya". KATA OMED. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Bus Damri di Palu Tersisa 14 Unit, Sejumlah Rute Ditutup". SultengTerkini (in Indonesian). 19 May 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Saleha, Nur (18 March 2021). Natalia, Kristina (ed.). "Bus Borlindo Palu-Makassar Resmi Beroperasi, Yuk Cek Promo Tiket Murah Hingga Akhir Maret". Tribunpalu.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Bus Palu Makassar: Jadwal dan Harga Tiket". Keposiasi. 2 January 2020. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b Saleha, Nur (22 April 2021). "Angkutan Umum Minim di Palu, Begini Penjelasan Dishub". Tribunpalu.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Angkot di Palu Tinggal 46 Unit yang Beroperasi". SultengTerkini (in Indonesian). 26 October 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "Becak Jadi Bentor, Simak Regulasi Wali Kota Palu - Respon Sulteng". news.allauction.live (in Indonesian). 15 June 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Burase, Amar, ed. (28 March 2021). "Car Free Day, Jaga Palu!". kumparan (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Lawani, Firmansyah (19 March 2021). "Ini Jalan-Jalan Palu Ditutup Saat Car Free Day". KAILIPOST (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Jamaluddin, Indar Ismail; Phradiansah (2020). "Media Siber Merespons Solidaritas Publik Terdampak Covid-19 di Palu Sulawesi Tengah". Prosiding Nasional Covid-19: 37–51.

- ^ Dede; Mingkid, Elfie; Golung, Anthonius (2019). "PERANAN JURNALIS MEDIA TELEVISI DALAM PROSES PEMULIHAN KORBAN BENCANA ALAM DI KOTA PALU (STUDI PADA PALU TV)". Acta Diurna Komunikasi. 1 (3). ISSN 2685-6999.

- ^ "Serah Terima Jabatan Kepala LPP RRI Palu – Pemerintah Kota Palu". 24 February 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Rahman, Muhammad Taupik. Hanafi, Imam (ed.). "Sejarah pertelevisian di Indonesia dari analog hingga digital". ANTARA News Kalimantan Selatan. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

References

[edit]Kahin, George McTurnan (1952). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9108-8.