Orson Squire Fowler

Orson Squire Fowler (October 11, 1809 – August 18, 1887) was an American phrenologist and lecturer. He also popularized the octagon house in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Early life

[edit]The son of Horace and Martha (Howe) Fowler, he was born in Cohocton, New York, He prepared for college at Ashland Academy and studied at Amherst College, graduating in the class of 1834.

Career

[edit]With his brother Lorenzo Niles Fowler, he opened a phrenological office in New York City. Orson wrote and lectured on phrenology, preservation of health, popular education and social reform from 1834 to 1887. Lorenzo and his wife Lydia Folger Fowler lectured frequently with Orson on the subject of phrenology.[1] The three were "in large measure" responsible for the mid-19th century popularity of phrenology.[2]

The practice of phrenology was frequently used to justify slavery and to advance a belief in African-American inferiority.[3] Fowler wrote that coarse hair correlated with coarse fibers in the brain, and indicated coarse feelings; that, he wrote, suggested that people of African descent had poor verbal skills and traits that were best suited for nursing children or waiting on tables.[4] At the same time, the phrenological journal edited by Fowler and his brother expressed strong abolitionist sentiments, calling slavery a "a monstrous evil."[5] Fowler's writings were also anti-Semitic.[6] For instance, in "Hereditary Descent" (1843), Fowler wrote that Jewish people were hereditarily acquisitive, deceitful, and destructive[7] (phrenology believes that none of these "organs" are negative as such, but all can be used for good).

Orson edited and published The Phrenological Journal, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from 1838 to 1842. He was a partner with Fowler & Wells, publishers, New York, from 1846 to 1854,[8] residing in Fishkill, New York, and Elizabeth, New Jersey. His sister, Charlotte Fowler Wells, and her husband, were involved in the publishing house, and after it became a stock company, she served as president.

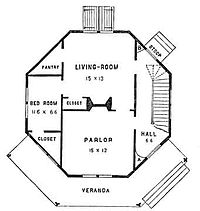

He built a home during 1848–1853, later termed Fowler's Folly, which was an octagon house overlooking the Hudson River. He authored a book, The Octagon House: A Home For All, which claimed benefits to living in such a home, and which was instrumental in igniting a fad that spread fairly widely in the United States and Canada.

He moved his office to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1863, residing in Manchester from 1863 to 1880. He resided in Sharon, New York, from 1883 until August 18, 1887, when he died.

Personal life

[edit]Fowler was married three times: to Mrs. Eliza (Brevoort) Chevalier; to Mrs. Mary (Aiken) Poole; and to Abbie L. Ayres. He had three children.

Fowler was a teetotaller and vegetarian.[9][10] He promoted a vegetarian diet in his book Physiology: Animal and Mental and was vice-president of the American Vegetarian Society in 1852.[10] He defended animal rights and opposed the slaughter of animals. His magazine The American Phrenological Journal also supported vegetarianism.[10]

Legacy

[edit]In 1856, followers of vegetarian Henry S. Clubb tried to establish Octagon City in Kansas. The design was inspired by Fowler's houses and would include octagonal houses and barns. The pioneers could not make it through the winter. The town of Fowler, Colorado, is named for Fowler.[11] Fowler too had an influence on modern psychology. He is remembered as a man of universal reform who preached for education and temperance. [citation needed] Orson, like his sister-in-law Lydia Fowler, held forth for the equality for women at a time when women had virtually no legal rights in the United States. [citation needed] Orson stood for children's rights when child labor was quite acceptable in the burgeoning industrial factories of his country. [citation needed] Fowler as a book seller and publisher was crucial in the original publication of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass and other works.[12]

Books

[edit]- Memory and Intellectual Improvement (1841)

- Physiology, animal and mental: applied to the preservation and restoration of health of body, and power of mind. Physiology: Animal and Mental] (1842)

- Matrimony, or Phrenology applied to the Selection of Companions (1842)

- Self Culture and Perfection of Character (1843)

- Education and Self-improvement

- Hereditary Descent, its Laws and Facts applied to Human Improvement (1843)

- Religion; Natural and Revealed (1844)

- Love and Parentage (1844)

- Maternity: or the Bearing and Nursing of Children (1848)

- The Octagon House: A Home for All (1848, the 1853 edition reprinted with new illustrations 1973)

- Self-Instructor in Phrenology and Physiology (1849), with Lorenzo Niles Fowler

- Sexual Science (1870)

- Phrenology Proved, Illustrated and Applied

- Amativeness

- Human Science, or Phrenology (1873)

- Creative and Sexual Science, or Manhood, Womanhood, and their Interrelations (1875)

- Sexuality Restored, and Warning and Advice to Youth Against Perverted Amativeness, Including Its Prevention and Remedies, as Taught by Phrenology and Physiology (1870) [13]

References

[edit]- ^ "Noted Phrenologist Dead: Lorenzo N. Fowler Succumbs to a Paralyzing Stroke" (obituary), The New York Times, 4 September 1896.

- ^ Engs, Ruth Clifford. Clean Living Movements: American Cycles of Health Reform, p.71, "The Fowlers" in "Inherited Realities, Phrenology, and Eugenic Undercurrents". Greenwood (2001).

- ^ Severson, Kim (August 22, 2017). "Tom Colicchio Changes His Restaurant's Racially Tinged Name". The New York Times.

- ^ Severson, supra; see also, Fowler, Orson Squire, "Hereditary Descent: Its Laws and Facts Applied to Human Improvement," Fowler and Wells Phrenological Cabinet (1848), at 134-35

- ^ "The American Phrenological Journal and Miscellany". A. Waldie. July 30, 1849 – via Google Books.

- ^ Pawley, Christine (June 30, 2009). Reading on the Middle Border: The Culture of Print in Late-Nineteenth-Century Osage, Iowa. Univ of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9781558497825 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fowler, Orson Squire (July 30, 1848). "Hereditary Descent: Its Laws and Facts Applied to Human Improvement". Fowlers and Wells – via Google Books.

- ^ J.E.S., "Phrenology and the Fowler Publications", The National Era, (Thursday, July 5, 1849), p.108.

- ^ Lane, Mills; Bullock, Marshall. (1985). North Carolina. Beehive Press. p. 231. "Orson Squire Fowler (1809–87) was a phrenologist, vegetarian, teetotaler, sex educator and publisher whose exotic, quixotic architectural ideas appealed to the emotional and idealistic age in which he lived."

- ^ a b c Iacobbo, Karen; Iacobbo, Michael. (2004). Vegetarian America: A History. Praeger Publishing. pp. 85-86. ISBN 0-275-97519-3

- ^ "Fowler, CO. - Community Powered! :: History, O.S. Fowler". www.fowlercolorado.com.

- ^ Madeleine, Stern (1971). Heads & Headlines: The Phrenological Fowlers. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 99–123. ISBN 0-8061-0978-5.

- ^ Sexuality Restored, and Warning and Advice to Youth Against Perverted Amativeness. H.O. Houghton. 1870. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Applegate, Debby. The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher. Doubleday, 2006.

External links

[edit]- Martin, John H. Orson Squire Fowler: Phrenology and Octagon Houses

- Works by Orson Squire Fowler at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Orson Squire Fowler at the Internet Archive

- Fowler, Colorado Archived 2008-09-12 at the Wayback Machine; named for O.S. Fowler

- Inventory of octagon houses Archived 2021-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- 1809 births

- 1887 deaths

- Amherst College alumni

- Temperance activists from New York (state)

- American vegetarianism activists

- People from Cohocton, New York

- People from Elizabeth, New Jersey

- People from Fishkill, New York

- People from Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts

- People from Sharon, New York

- Phrenologists

- Scientists from Philadelphia

- Octagon houses