Potter Building

| Potter Building | |

|---|---|

Seen from across Park Row (2012) | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Financial District, Manhattan, New York |

| Address | 35–38 Park Row or 145 Nassau Street, New York, NY 10038 |

| Coordinates | 40°42′42″N 74°00′24″W / 40.71167°N 74.00667°W |

| Construction started | 1883 |

| Completed | 1886 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 11 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Norris Garshom Starkweather |

Potter Building | |

New York City Landmark No. 1948

| |

| Location | 35–38 Park Row, Manhattan, New York |

| Built | 1883–1886 |

| Architect | Norris Garshom Starkweather |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne, neo-Grec |

| Part of | Fulton–Nassau Historic District (ID05000988) |

| NYCL No. | 1948 |

| Significant dates | |

| Designated CP | September 7, 2005[2] |

| Designated NYCL | September 17, 1996[1] |

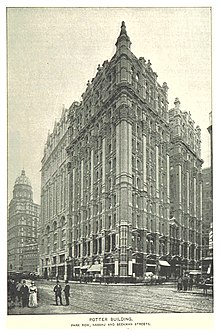

The Potter Building is a building in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The building occupies a full block along Beekman Street with the addresses 38 Park Row to its west and 145 Nassau Street to its east. It was designed by Norris G. Starkweather in a combination of the Queen Anne and neo-Grec styles, as an iron-framed structure.

The Potter Building employed the most advanced fireproofing methods that were available when the building was erected between 1883 and 1886. These features included rolled iron beams, cast iron columns, brick exterior walls, tile arches, and terracotta. The Potter Building was also one of the first iron-framed buildings, and among the first to have a C-shaped floor plan, with an exterior light courtyard facing Beekman Street. The original design remains largely intact.

The building replaced a former headquarters of the New York World, which was built in 1857 and burned down in February 1882. It was named for its developer, the politician and real estate developer Orlando B. Potter. The Potter Building originally served as an office building with many tenants from the media and from legal professions. It was converted into apartments from 1979 to 1981. The Potter Building was designated a New York City landmark in 1996 and is also a contributing property to the Fulton–Nassau Historic District, a National Register of Historic Places district created in 2005.

Site

[edit]The Potter Building is in the Financial District of Manhattan, just east of New York City Hall, City Hall Park, and the Civic Center. The building abuts Park Row for about 97 feet (30 m) to the west, Beekman Street for 144 feet (44 m) to the south, and Nassau Street for about 90 feet (27 m) to the east. The northern wall abuts 41 Park Row on the same block for 104 feet (32 m).[3][4] The Morse Building and 150 Nassau Street are across Nassau Street, while 5 Beekman Street is across Beekman Street.[5] The corner of Park Row and Beekman Street is at an acute angle.[6] The Potter Building's addresses include 35–38 Park Row, 2–8 Beekman Street, and 138–145 Nassau Street.[1][a]

Architecture

[edit]The 11-story Potter Building is arranged in a mixture of styles, including the Queen Anne, neo-Grec, Renaissance Revival, and Colonial Revival styles. As a result, it stands out from the surrounding buildings.[7] The Potter Building's architect, Norris Garshom Starkweather, was known for designing churches and villas in the mid-Atlantic states.[8][9] The building measures 165 feet (50 m) tall from sidewalk to roof, with finials extending upward another 30 feet (9.1 m).[10] The original design remains mostly intact.[1]

The Potter Building employed the most advanced fireproofing methods available at the time of construction, due to its predecessor having burned down. This included the use of rolled iron beams, cast iron columns, brick exterior walls, as well as tile arches and terracotta.[11][12][13] Five iron companies provided the material.[7][14] The fireproofing is insulated by the brick-and-terracotta facade.[15] The Potter Building, characterized by architectural historian Robert A. M. Stern as a "textbook case for fire retardation", was the last major building to be supported by load-bearing walls, which would have been unnecessary in light of the iron superstructure.[16]

Form

[edit]The Potter Building is U-shaped, with a "light court" within the two arms of the "U", facing outward toward Beekman Street.[6][17] The building is one of the city's oldest extant structures with a light court.[6] The Real Estate Record and Guide said that "the rooms on each side are made symmetrical in spite of the irregularity of the lot; the irregularity, of course, appearing in the court itself".[18] A writer for the Fireman's Herald stated that the court split the facade so that "it looks almost like two buildings".[12] There is a fire escape in the middle of the light court.[19]

Facade

[edit]At the time of the Potter Building's construction, the facades of many 19th-century early skyscrapers consisted of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a base, midsection, and capital. The base comprises the bottom two stories, the midsection included the middle seven stories, and the capital was composed of the top two floors.[19] The base has an iron facade and the remaining stories have a red brick and terracotta facade.[20][21] Each side has similar ornamentation, containing column capitals, pediments, corbels, panels, and segmental arches made of terracotta.[6] The ornamental detail is elaborately designed in the classical style and includes massive capitals atop the vertical piers, as well as triangular and swans'-neck pediments.[22][23]

The piers divide the facades into multiple bays, which each contain two windows on each floor.[7] The piers, clad with brick above the second floor, are 4.5 feet (1.4 m) wide at the base, with a uniform width for the building's entire height, but range in thickness from 40 inches (1,000 mm) at the first floor to 20 inches (510 mm) at the eleventh floor. They contain concealed flues that ventilate the gases from the building's furnaces into hidden chimneys underneath the finials atop each pier. The lintels on the upper stories, clad with terracotta, consist of four parallel wrought-iron beams with a width of 21 to 32 inches (530 to 810 mm) between flanges.[10] The lintel beams sit atop iron plates embedded within the masonry of each pier and anchored with a twisted iron strap.[24]

Because of the presence of elevator lobbies at the northern end of the building, the northernmost bays on Park Row and Nassau Street are wider. At Park Row and Beekman Street, a 270-degree-wide column rounds out the corner.[6]

The Potter Building is among the oldest remaining buildings in New York City to retain architectural terracotta. The terracotta was sculpted by the Boston Terra Cotta Company and was more highly detailed than in other contemporary buildings.[25][26][27] At the time, there were no terracotta companies in New York City,[27] and four other firms competed to supply the building's terracotta.[28][29] The structure ultimately included 540 short tons (480 long tons; 490 t) of terracotta.[8] Boston Terra Cotta Company superintendent James Taylor supervised the placement of the terracotta.[25][30] The fourth and eighth floors contain windows ornamented with terracotta segmental arches; the third, fifth, sixth, seventh, and tenth-story windows contain terracotta corbels; and the eleventh-story windows have terracotta hoods.[19]

Features

[edit]

The foundation walls of the Potter Building were 4 feet (1.2 m) thick and sunken to a depth of 22.5 feet (6.9 m). The underlying bedrock layer was more than 100 feet (30 m) below the ground, so the foundations were placed on separate pier footings.[9] The site is 44 feet (13 m) above groundwater. During the construction of the New York City Subway's IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (2 and 3 trains) underneath Beekman Street in 1915, the southern elevation was underpinned using concrete-and-steel tubes sunk to a depth of 56 to 59 feet (17 to 18 m), underneath the groundwater level.[9][31]

The exterior columns are made of iron.[12] All of the above-ground floors were built on girders made of rolled iron.[21] The girders were 15 inches (380 mm) thick and range from 13.75 to 16.25 feet (4.19 to 4.95 m) long. The floor beams, 10.5 inches (270 mm) thick, sit atop the flanges of each girder; their centers are set 4.5 feet (1.4 m) apart, and most of the beams have a uniform length of 18.33 feet (5.59 m).[32] Flat brick arches were placed within each set of floor beams and were leveled with concrete, brick, and stone aggregate. The floors were finished with wood, while the ceilings were finished in plaster.[22]

Potter's original plans for the building were for the first floor to contain bank offices and for the upper floors to be used by other businesses. He wished for the Potter Building to be "an ornament to the neighborhood".[33] Inside were originally 351 suites that could be used by up to 1,800 people at a time.[34] The ceilings of each story are 11 feet (3.4 m) high. The building's upper floors were later converted into apartments of 1,700 square feet (160 m2) each, though the apartments retained the 18.5-inch-thick (47 cm) walls.[35]

History

[edit]Context

[edit]The Potter Building lot, and the adjoining lot immediately to its north (which is occupied by 41 Park Row), was the site of the Old Brick Church of the Brick Presbyterian Church, built in 1767-1768 by John McComb Sr.[36][37] Starting in the early 19th century and continuing through the 1920s, the surrounding area grew into the city's "Newspaper Row"; several newspaper headquarters were built on Park Row, including the New York Times Building, the Park Row Building, the New York Tribune Building, and the New York World Building.[37][38] Meanwhile, printing was centered around Beekman Street.[37][39] When the Brick Presbyterian Church congregation moved uptown to Murray Hill in 1857,[40][41] Orlando B. Potter, a politician and a prominent real estate developer at the time, purchased the southern half of the Old Brick Church lot.[17][37][13][42] Potter erected a five-story Italianate stone building on the lot for $350,000 (equivalent to $11 million in 2023[b]); it became the first headquarters of the New York World, which was established in 1860. Potter purchased the building outright in 1867.[37][43]

A fire broke out in the World building around 10:00 p.m. on January 31, 1882,[44][45] supposedly because of a draft of wind from the nearby Temple Court Building.[12][46] The fire destroyed much of the block within a few hours, killing six people[47] and causing more than $400,000 in damage (equivalent to $13 million in 2023[b]);[44][45] The World building was said to have "made itself notorious the country over for burning up in the shortest time on record",[10][12][37] and it took a week to examine the wreckage,[47] Several days after the fire, the Real Estate Record and Guide said that "the ground is so valuable that it will no doubt be immediately built upon".[45][48]

Construction

[edit]

Potter sought to replace the burned-down edifice with a fireproof structure,[7][10][13] having incurred more than $200,000 of losses (equivalent to $6 million in 2023[b]) in addition to loss of income.[49][50] By mid-February 1882, Potter was planning to construct an 11-story building at the site of the old World building, which he specified should be fireproof.[33] In 1883, Starkweather presented plans for the structure, of which the first two stories would have an iron facade and the remainder would have a brick facade.[20] Potter decided to defer construction for one year due to the high cost of acquiring materials.[33]

Construction of the foundation started in April 1883.[51] To test the relative strength of iron versus wooden floor beams, Potter built two small, nearly-identical structures, one with each material. After setting them on fire for two to three days, Potter determined that the iron structure was more suitable for use, since the iron floor suffered little damage compared to the totally-burned wooden floor.[12][50] Plans for the Potter Building were filed with the New York City Department of Buildings in July 1883, at which point it was supposed to cost $700,000 (equivalent to $23 million in 2023[b]).[21]

Construction was underway by mid-1884.[52] Workers were hired by the day, rather than contracted for the entire project.[12] Since the World building fire had occurred during the construction of Potter's 750 Broadway building in NoHo, further uptown, workers from the 750 Broadway project were also contracted to work on the Potter Building. Construction was delayed in May 1884 due to a bricklayers' strike, and the costs increased to $1.2 million (equivalent to $41 million in 2023[b]).[7] Work was also delayed by a painters' and carpenters' strike in 1885.[53] The building was completed in June 1886.[7] Potter's involvement in the process of terracotta selection was so extensive that he founded the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Company with his son-in-law Walter Geer.[8][27][16] An 1888 brochure for the company stated that the Potter Building was "an example of the best use of terra-cotta, both for constructive and ornamental purposes".[25]

Use

[edit]

At the time of its completion, the Potter Building was among the tallest in the area, towering above every other structure except the New York Tribune Building.[15] The Boston Globe called the Potter Building "the tallest straight-wall building in the world".[34] The 1892 King's Handbook of New York City stated that newspapers, magazines, insurance companies, and lawyers occupied 200 offices within the building.[54][55] The newspaper tenants included The Press, a Republican Party-affiliated penny paper, as well as The New York Observer. The Potter Building was also occupied by paper manufacturers Peter Adams Company and Adams & Bishop Company, the Mutual Reserve Fund Life Association insurance company, and the Otis Elevator Company. In addition, Potter occupied the top floor, and his New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company also had offices in the building.[27][55]

Potter died in 1894,[56] and the building was given over to his estate.[55][57] O.B. Potter Properties acquired the building from Potter's estate in 1913.[55] The Potter Building, along with some of the Potter estate's other properties (such as the Empire Building), was sold in 1919 to the Aronson Investing Company.[15][58][55] The building's ownership was then transferred several times within a decade: the Parbee Realty Corporation acquired the structure in 1923,[55] followed by A.M. Bing & Son in 1929,[3] and the 38 Park Row Corporation in 1931, before Parbee re-acquired the Potter Building the following year.[55] The Seaman's Bank for Savings acquired the structure at a foreclosure auction in 1941,[59] and four years later, sold it to Beepark Estates.[55] Tenants throughout this time included the United States Housing Authority, accountants, and lawyers.[55][60] The 38 Park Row Corporation purchased the building in 1954.[55]

The New York World and Tribune buildings to the north were demolished in the 1950s and 1960s, and Pace College (later Pace University) built 1 Pace Plaza on the site of the latter.[61] The university also acquired the Potter Building and other nearby buildings in 1973, with plans to destroy them and build an office tower. These plans did not proceed and Pace sold the building in 1979 to a joint venture named 38 Park Row Associates,[55] composed of Martin Raynes and the East River Savings Bank.[62] 38 Park Row Associates converted the building into residential cooperatives and gave it to the 38 Park Row Residence Corporation in 1981.[55]

Following the residential conversion, a structural engineer noted that the facade had "significant deterioration particularly in the mortar jointings". The Potter Building's co-op board subsequently arranged for a renovation of the facade in 1992-1993, to be carried out by Siri + Marsik and Henry Restoration.[35] The Potter Building, along with the Manhasset Apartments and 110 East 42nd Street,[63] was made a New York City designated landmark on September 21, 1996.[1] A controversy ensued in 1999 when the Blimpie restaurant at the Potter Building's ground level decided to place outdoor seating on Nassau Street, which had recently been converted from a weekday-only pedestrian zone into a full-time pedestrian plaza. Residents of the Potter Building complained that the seating violated a city ordinance on sidewalk cafes.[64] In 2005, the Potter Building was designated as a contributing property to the Fulton–Nassau Historic District,[23] a National Register of Historic Places district.[2]

Critical reception

[edit]

Lower Manhattan's late-19th century skyscrapers generally received mixed reception,[6] and the Potter Building was especially criticized by professional architectural journals.[65] A Real Estate Record and Guide writer remarked in 1885 that "there is not an interesting or refined piece of detail in the whole building".[18] The critic also said that the building's design focused too much on its vertical aspect,[18][16] though this contrasted with the opinions of other contemporary critics, who generally saw vertical emphasis favorably.[6] In 1889, a writer for the same magazine compared the Potter Building with the Times Building at 41 Park Row, saying that the Potter Building's architect "contrived to make [it] appear at once monotonous and uneasy".[66]

There were also positive reviews of the design. An 1885 Carpentry and Building article stated that the building was "one of the most conspicuous new buildings in the lower part of New York City", because of its juxtaposition of iron with brick and terracotta.[12] The King's Handbook described the Potter Building as being among the city's "great and illustrious monuments of commercial success",[54] while an 1899 architecture guidebook said that the Potter Building's "design is unusual and perhaps excessive in detail, but has great interest in the disposition of its masses."[67] Later, in 1991, New York Times writer David W. Dunlap described the Potter Building as "almost hallucinatory in its Victorian encrustation".[68] Architectural writers Sarah Landau and Carl Condit characterized the Potter Building as "distinguished above all by its ruggedly picturesque red brick and cast-iron-clad outer walls abundantly trimmed with terra-cotta".[17]

References

[edit]Informational notes

- ^ Address numbers on the southeast side of Park Row run consecutively because the northwest side of the street is occupied by City Hall Park. In the area's standard address numbering system, odd- and even-numbered addresses are on opposite sides of the street.[5]

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

Citations

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 1.

- ^ a b "National Register of Historic Places 2005 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2005. p. 242. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "A.M. Bing & Son Buy the Potter Building; Operators Acquire Eleven-Story Offices at 38 Park Row-- Former Wallack's Theatre Sold". The New York Times. April 18, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 137, 139.

- ^ a b "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 414.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 139.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The New Potter Building". Fireman's Herald. Building. Vol. 1–3. William T. Comstock. 1883. p. 89. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2005, p. 29.

- ^ Building Age. David Willaims Company. 1885. pp. 161–162. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Potter Building, Opposite City Hall, is Sold". New-York Tribune. December 5, 1919. p. 21. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. Monacelli Press. pp. 415, 418. ISBN 978-1-58093-027-7. OCLC 40698653.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 137.

- ^ a b c "The Potter Building" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 35, no. 901. June 20, 1885. pp. 701–702. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Out Among the Builders" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 32, no. 800. July 14, 1883. p. 501. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c "A New Building in Park-Row". The New York Times. July 20, 1883. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, p. 141.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2005, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 139, 141.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Geer 1920, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2005, p. 30.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Geer 1920, p. 84.

- ^ Geer 1920, pp. 87–88.

- ^ "Jacking Tests on Piles". Engineering News. Vol. 74. September 16, 1915. p. 559. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 141, 414.

- ^ a b c "Out Among the Builders" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 29, no. 727. February 18, 1882. p. 142. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Heaven-Kissing Roofs". The Boston Globe. March 7, 1887. p. 3. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Postings: $1 Million Facelift; Preserving the Terra Cotta". The New York Times. March 8, 1992. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Geer 1920, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 3.

- ^ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 893. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- ^ "Paternoster Row of New-York". New York Mirror. Vol. 13. May 14, 1836. p. 363. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "City Items. The New "Brick Church"". The New York Times. September 30, 1858. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Knapp, Shepherd (1909). A history of the Brick Presbyterian church in the city of New York. New York: Trustees of the Brick Presbyterian church. pp. 277–292. OCLC 1050750793.

- ^ Geer 1920, p. 77.

- ^ Potter 1923, p. 40.

- ^ a b "Flames in a Death-Trap; the Potter Building Completely Destroyed. Loss of at Least Five Lives and $700,000 in Property". The New York Times. February 1, 1882. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c "That Fire" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 29, no. 725. February 4, 1882. p. 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "History of architecture and the building trades of greater New York". Union History Co. 1899. p. 317. hdl:2027/pst.000004890652. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2020 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b "No More Bodies Found.; the Work of Excavation in the Ruins of the Potter Building". The New York Times. February 6, 1882. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Potter 1923, p. 129.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 11.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 31, no. 788. April 21, 1883. p. 163. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Prominent Buildings Underway" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 33, no. 836. March 12, 1884. p. 289. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Strikers Gain a Victory.; They Make a Stubborn Contractor Yield Every Point". The New York Times. August 20, 1885. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ a b King, Moses (1892). King's Handbook of New York City: An Outline History and Description of the American Metropolis. Moses King. p. 778. OCLC 848600041.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 7.

- ^ "Orlando B. Potter Dead; Fell in Fifth Avenue and Expired Immediately". The New York Times. January 3, 1894. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Transfer of the Potter Estate". The New York Times. February 1, 1894. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Potter 1923, p. 240.

- ^ "Old Potter Building is Bid in by Bank; 'Newspaper Row' Structure Goes to Seamen's Savings". The New York Times. April 9, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Fpha Gets Space for New Offices; Leases in 38 Park Row in Consolidation Plan -- Hatters Rent Broadway Store". The New York Times. September 14, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Porterfield, Byron (May 20, 1966). "'Newspaper Row' Shrinking Again; The Old Tribune Building on Nassau Is Giving Way to Pace College Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (July 29, 1979). "Wall St. Image Facing Change As Apartments Replace Offices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Three Buildings Join City's Landmarks List". The New York Times. September 22, 1996. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ Stamler, Bernard (May 16, 1999). "Sidewalk Cafes Up Close; Outdoor Seats Outrage Some On Nassau St". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 142.

- ^ "The 'Times' Building" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 43, no. 1087. January 12, 1889. p. 32. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ New York Union History Company (1899). History of Architecture and the Building Trades of Greater New York. History of Architecture and the Building Trades of Greater New York. Union History Company. p. 100. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (September 15, 1991). "Hidden Corners of Lower Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

Bibliography

- "Fulton–Nassau Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 7, 2005.

- Geer, Walter (1920). The story of terra cotta. The Library of Congress. New York, T. A. Wright. OCLC 1157574719.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- Potter, Blanche (1923). More Memories: Orlando Bronson Potter and Frederick Potter. J.J. Little & Ives Co.

- "Potter Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 17, 1996.

External links

[edit]- 1886 establishments in New York (state)

- Apartment buildings in New York City

- Cast-iron architecture in New York City

- Civic Center, Manhattan

- Commercial buildings completed in 1886

- Financial District, Manhattan

- Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Residential buildings completed in 1886