Nicolae G. Socolescu

Nicolae Gheorghe Socolescu | |

|---|---|

| Niculae Gheorghe Socol | |

| Born | around 1820 |

| Died | 1872 Ploiești, Romania |

| Nationality | |

| Other names | Nicolae Gh. Socolescu; Nicolae G. Socolescu; Niculae Gheorghe Socol; Niculae Gh. Socol; Niculae G. Socol |

| Alma mater | Academy of Fine Arts Vienna |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Years active | 1846-1872 |

| Children | Toma N. Socolescu, Ion N. Socolescu |

| Parent | G. Streza Socol |

| Practice | Architecture, urban planning, civil construction, painter. |

| Buildings | Europa, Carol and Victoria hotels in Ploiești, manors, villas and stores in the Prahova county. |

| Design | Neoclassical architecture |

Nicolae G. Socolescu (born Niculae Gheorghe Socol) was a 19th-century Romanian neoclassical and baroque architect.

Biography

[edit]Originally from Transylvania[e 1] in the Austrian Empire, a native of the village of Berivoiul Mare[b 1][c 1] in Țara Făgărașului, he settled in Wallachia (now Romania) in Ploiești, along with his four brothers, all builders, around 1840–1846.[a 1][d 1] He studied architecture in Vienna.[a 2][d 2] In 1846, he began his career as an architect and a master builder.[a 1][d 1] After leaving the Austro-Hungarian Empire for Romania, as soon as he arrived in Ploiești, he changed his name to Nicolae G. Socolescu.[a 3][d 3] He was one of Prahova County's leading architect-builders in the mid-19th century. He died in 1872[1] and is buried in the courtyard of the Sfântul Spiridon church in Ploiești.[a 4][d 4]

Genealogy

[edit]The Socol family of Berivoiul Mare, part of Țara Făgărașului is a branch of the Socol family of Muntenia, which lived in the county of Dâmbovița. A 'Socol', great boyar and son-in-law of Mihai Viteazul (1557–1601), had two religious foundations in Dâmbovița county, still existing, Cornești and Răzvadu de Sus. He built their churches and another one in the suburb of Târgoviște. This boyar married Marula, daughter of Tudora din Popești, also known as Tudora din Târgșor,[2] sister of Prince Antonie-Vodă. Marula was recognized by Mihai Viteazul as his illegitimate daughter, following an extra-marital liaison with Tudora. Marula is buried in the church of Răzvadu de Sus, where, on a richly carved stone slab,[3] her name can be read.

Nicolae Iorga, the great Romanian historian and friend of his grandson Toma T. Socolescu, found Socol ancestors among the founders of the City of Făgăraș in the 12th century.[b 2] In 1655, the Prince of Transylvania George II Rákóczi ennobled an ancestor of Nicolae G. Socol: "Ștefan Boier din Berivoiul Mare, and through him his wife Sofia Spătar, his son Socoly, and their heirs and descendants of whatever sex, to be treated and regarded as true and undeniable NOBLEMEN.",[b 3] in gratitude for his services as the Prince's courier in the Carpathians, a function "which he fulfilled faithfully and steadfastly for many years, and especially in these stormy times [...]".[b 3][b 4] Around 1846, five Socol[b 5] come to Muntenia, from Berivoiul Mare, in the territory of Făgăraș.

"Five brothers crossed the mountains, all builders, from the Făgăraș region, a village at the foot of the mountains, Berivoiul Mare, where the name of Socol is still widespread today, and where one of their ancestors is said to have come from Munténie, namely from the region of Târgoviște, which is the home of the Socol family, being to this day, near Târgovişte, Valea lui Socol (the Socol Valley), as well as their two founding churches, in Răzvadu de Sus and Cornești.[a 5][c 2]"

One of the brothers was architect Nicolae Gh. Socol (??-1872). He settled in Ploiești around 1840–1845, and named himself Socolescu. He married Iona Săndulescu, from the Sfantu Spiridon suburb. He had a daughter (she died in infancy) and four sons,[a 6][d 5] two of whom became major architects: Toma N. Socolescu and Ion N. Socolescu. The lineage of architects continues with Toma T. Socolescu, and his son Barbu Socolescu.

The historian, cartographer and geographer Dimitrie Papazoglu evokes, in 1891,[e 2] the presence of Romanian boyars of the first rank Socoleşti, in Bucharest, descendants of Socol from Dâmbovița. Finally, Constantin Stan also refers, in 1928, to the precise origin of Nicolae Gheorghe Socol :

"At the foot of the Carpathians, on the right bank of the stream of the same name, lies the commune of Berivoiul Mare [...], one of the oldest villages in the Olt household [...]. The inhabitants are composed of serfs and former boyars. [...], and the Romanian boyar families were: Socol, Boyer, Sinea and Răduleț, soldiers with border guard privileges.[...] The G. Streza Socol family gave birth to Nicolae Socol, a graduated architect from Vienna, who settled in the town of Ploeşti with several of his brothers around the middle of the last century[e 3]

| Niculae Gheorghe Socol (~1820-1872) architect and builder in Ploiești | Ioana Săndulescu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alexandrina Nicolau (1860–1900) | Toma N. Socolescu (1848–1897) architect and builder in Ploiești | Nicolae N. Socolescu timber merchant | Ghiță N. Socolescu artist painter, dead during his graduate studies | Ion N. Socolescu (1856–1924) architect | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Florica Tănescu (1887-1969) | Toma T. Socolescu (1883–1960) professor-architect | Florica T. Socolescu | Smaranda T. Socolescu | Ioan T. Socolescu | Coralia-Ioana-Margareta T. Socolescu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mircea Socolescu (1907–1978) settled in France in 1945, married without children | Toma Gheorghe Barbu Socolescu (1909–1977) professor-architect | Irena Gabriela Vasilescu (1910–1993) artist painter, teacher | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mihai Ștefan Marc Socolescu (1942–1994) teacher | Maria Lois (1942-2021) teacher | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Laura Socolescu (1967) settled in France – artist-choreographer, dancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Architectural achievements

[edit]The period in which Socol settled in Wallachia corresponded to a political and cultural desire, widely shared in the country, to move closer to the West and away from Eastern culture. A genuine desire to assimilate Western values permeated all the Romanian society. Architecture has obviously been one of the most visible expressions of this trend.

As a result, demand for neo-classical and baroque buildings - the architectural styles in vogue in Western Europe - quickly took over from other styles.[4] In addition, the city was booming economically and commercially, with the construction of the first oil refineries and factories.[e 4]

Applying the concepts and style he learned from his Viennese architectural studies, Socol's works include neo-classical and neo-Gothic but also eclectics.[c 3]

He was the first Romanian architect to settle in Ploiești, having practiced architecture in the region for 30 years as early as 1840.[a 7][d 6]

Most of the architects practicing in Romania at the time were foreigners,[e 5] often from Transylvania, and few reached the level of the foreign architects brought in by the princes and rulers of the epoch.[a 2][d 2] It should be remembered that the first architectural education in the country dates back only to 1864, with the creation of the Architecture section within the School of Fine Arts, a section created by architect Alexandru Orăscu.[a 8][d 7] The architect responded to a strong demand for occidentalization and also for the transformation of traditional inns (han) into more comfortable single-storey houses, or even upmarket hotels. Morevor, he built numerous stores and boutiques for Ploiești merchants. Lastly, he was one of the founders and builders of the Sfântul Spiridon church in the suburb near the city center, where he lived.[c 4][d 8]

In Ploiești

[edit]- The family home, located in Ploiești suburb called Sfântul Spiridon,[a 9][c 4][d 9] circa 1846. It was destroyed during the construction of the Central Market Halls of Ploiești in the 1930s.[b 6]

- Europa hotel, it originally hosted stores on the first floor and residential apartments upstairs,[a 10][c 4][d 10] built for the Radovici brothers. They played leading political roles at the time: Alexandru G. Radovici, a politician of national stature who was elected deputy, senator, mayor of Ploiești, but also minister of industry and commerce and vice-president of the Chamber of Deputies before 1914, ending up Director of the Central Bank during the war,[d 11][5] and his brother the Dr. Ioan G. Radovici.[d 12] Later renovated, then raised by one storey and attic-roofed by his grandson Toma T. Socolescu before 1914, it was badly damaged by the American bombardments of 1944, poorly rebuilt, and finally destroyed in the 1960s-70s by the Communists to make way for the administrative palace.[f 1]

- Victoria hotel, on the strada Romană, which for a time remained the property of Tane and Panait Tănescu.[a 11][d 13]

|

|

|

| Niculae Gh. Socol's hotels. |

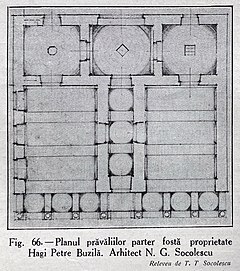

- The Hagi Petre Buzilă or Bujilă's inn (hanul Hagi Petre Buzilă), in 1858, at the crossroads of calea Câmpinii[6] and strada Romană.[a 12][d 14] The former Tribunal moved there in November 1860, renting its premises.[a 13][d 15] It was bombed in 1944 and destroyed immediately after the war.[f 2][7]

- The inn of Hagi Niţă Pitiși or Hagi Niţă Pittiș, in 1857, located near the halls.[a 14][d 16] It is in the same style as the Hagi Petre Buzilă inn.[a 12][d 14] In 1937, Toma T. Socolescu made a description of the master of the house:[a 15][d 17]

The building was still intact in 1938. Damaged by the 1944 American bombings of 1944, it was rebuilt in a completely different style to the original (without decorations and with an additional storey). It was eventually demolished in the 1950s, and replaced by a seven-storey, unstyled Communist housing block.[f 3]"A native of Transylvania, he was a leading merchant on the strada Lipscani; a religious man, he closed his store during religious services on Sundays and public holidays, and was much appreciated by his fellow citizens. The building is still preserved in its original shape."

- A big boyar house for the commissioner Panaiote Filitis,[a 16][d 18] located calea Câmpinii.[6] A house that he also restored later for the new owner: Dumitru D. Hariton, mayor of Ploiești from May 1892 to August 1894.[a 2][d 2] The building has since been demolished.

- A store with several boutiques, located at the intersection of calea Romană and calea Câmpinii[6] for Hagi Petre Buzilă, circa 1852.[a 7][d 6] His grandson Toma T. Socolescu described its architecture 70 years later in his work Arhitectura în Ploești, studiu istoric:[8]

Half of it was later destroyed for another construction. It no longer exists today."It was one of the most successful and characteristic buildings of this so-called Austrian style, but which had the stamp of northern Italian influence: a neo-Gothic one, with rich and fine ornamentation, under cornices as well as in the tympanums of the arches, and which would have deserved to be kept, especially since it was still very well preserved".[a 7][d 6]

|

|

|

| Niculae Gh.Socol's inns. |

Outside Ploiești

[edit]

- In Câmpina, around 1850, Zaharia Carcalechi's house, journalist and publisher native from Brașov. It later became, in 1877, the town hall of Câmpina.[a 2][d 2] Restored by his son Toma N. Socolescu around 1880,[c 1] it is located at the intersection of Doftanei avenue,[9] and the city's central boulevard, Carol I Boulevard.[10] It was demolished in 1922, and another town hall was built on the same site.[11]

- Bărcănescu or palatul Bărcănescu family Palace in the municipality of Bărcănești.[a 2][d 2]

- Many buildings in Târgoviște.[a 2][d 2]

Attributed works

[edit]The absence of archives and written traces in the 19th century makes it difficult to attribute certain works.[e 6] However, the work of Toma T. Socolescu in his historical study on the architecture of Ploiești, and in particular his research around 1937 in the city court archives, as well as in those of the town hall,[a 17] in order to find conclusive evidence on ancient constructions, allows other works to be attributed to the architect. The author of the study, a connoisseur of Romanian architecture from the 18th century,[12] makes an analysis of the buildings styles and relies on testimonials from descendants:[a 2][d 2]

"From their architecture, from the period in which they were built, and from the assertion of the old man V. Pitişi, son of Hagi N. Pitişi, I can state with certainty that these two inns, which are undeniably made by the same architect, and the Moldavia hotel, the I. Radovici's house as it was (today hotel Carol), the house of brothers I. and G. Radovici (today hotel Europa), restored by myself, the former Victoria hotel (Fig. 65) once owned by Tane and Panait Tănescu, the former Panaiote Filitis's house on calea Câmpinii,[6] later owned by D. D. Hariton, — also on Câmpinii street, the Petrache Filitis'house, later by N. Rășcan, the Sfântul Spiridon church, the row of stores P. P. Panțu, now transformed into a facade, formerly owned by Hagi Jecu and many others in the same style and from the same period were built — both plans as well as execution, as was usual at the time, by Nicolae G. Socolescu (originally Socol), building architect”.[13]

We can thus list the works attributed to Nicolae Gheorghe Socolescu by Toma T. Socolescu:

- The Moldavia hotel, resulting from the transformation of a post office for Nica Filip family, still standing in 1937.[a 18][d 19][e 6]

- The luxury hotel Carol Palace after the transformation of Dr. I. Radovici residence.[a 19][d 20] It was located at strada Unirii and strada Romană intersection. It was destroyed by the communists in the 1980s to make way for the extension of the new telecommunications building, which was in turn abandoned in the 2000s.[f 4]

- Petrache Filitis's house,[a 2][d 2] on calea Câmpinii,[6] at the crossing of strada Carpați, which later became N. Rășcan street. Degraded over time by a succession of tragic events: the 1940 earthquake, the American bombings of 1944, then the dispossession by the communists, it ended up like most of the houses unmaintained or unconsolidated by the communists: destroyed in the 1980s.[f 5]

- Sfântu Spiridon church in the suburb of the same name where he lived.[a 2][d 2] The church was consecrated on December 11, 1854.[a 1][d 1] Among the benefactors, the architect's name appears on a pisania (engraved stone plaque) above the church door.[e 7]

- A row of stores for P. P. Panţu, formerly owned by Hagi Jecu, whose facades were later transformed.[a 2][d 2]

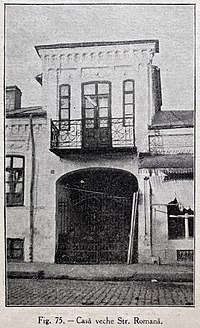

- Two buildings constructed by Nicolae Socol and his son Toma N. Socolescu on strada I. G. Duca (now Romană), the first on the corner with strada Negustori, with stores on the first floor, and the second a small dwelling house on the same I. G. Duca street at no. 108. On their frontispiece, are drawn the two lions found in other buildings of the period, all in a delicate neo-classical style.[a 20][d 21] The first house now located at the corner of strada Romană and strada Ştefan Greceanu, is still visible, it is the Călugăru inn or hanul Călugăru. The wing located at strada Romană is clearly recognizable,[a 21][d 22] with its entrance gate unchanged fromthe original, although the pediment of the entrance for carts and carriages has been disfigured. This construction would therefore be the only one still existing and recognizable today in Ploiești, built by Niculae Gheorghe Socol.

Legacy

[edit]Influenced by the Austrian classical and baroque styles he observed in Vienna, Nicolae G. Socolescu was a neoclassical architect.[e 8] He was among the first active Romanian architects. He participated in the movement of modernization of the country in architecture and civil construction.[e 9] Along with the architects of his time, all of whom had been trained in Western Europe, he passed on to the country what he had seen and learned during his stay in Vienna. Western styles, with their strong cultural influence: Neoclassical, Baroque, Italian or Neo-Gothic, were highly prized by Prahova's merchants, its main customers, who were also eager to westernize[e 10] and detach themselves from Oriental influence, in particular that of their former protector: the Ottoman Empire, from which the country was in the process of freeing itself completely. Socol marked Ploiești with his style for almost 100 years (1846 to 1944), and his art, through the Carol Hotel, was still present until 1980, before Ceaușescu's systematization.

Almost all of his works have been destroyed or radically transformed over time.[e 11] The construction of the Central Market Hall (1935–1936) initially necessitated the destruction of some of his works.[e 12] It was the American bombings of 1944 that destroyed a substantial part of his achievements, most of which were still standing at the time. The communist systematization delivered the final blow and erased almost all visible traces of his architectural work.[e 7] Only the building of the former Călugăru inn, in Ploiești, remains.[14] Socol, however, laid the foundations for the creative and innovative activity of his descendants: Ion N. and then Toma T. Socolescu. His financial comfort was also a stepping stone[e 7] for his two sons who took up the torch of architecture: Ion N. Socolescu and Toma N. Socolescu and left a deep mark on Romanian architecture.[15]

|

|

| Niculae Gh.Socol's stores. |

Bibliography

[edit]- (in Romanian) Socolescu, Toma T. (2004). Amintiri [Memories] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Caligraf Design. ISBN 973-86771-0-6.[16]

- (in Romanian) Socolescu, Toma T. (2004). Fresca arhitecților care au lucrat în România în epoca modernă 1800 - 1925 [Fresco of architects who worked in Romania in the modern era 1800 - 1925] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Caligraf Design. ISBN 973-86771-1-4.[17]

- (in Romanian) Socolescu, Toma T. (1938). "Preface by Nicolae Iorga". Arhitectura în Ploești, studiu istoric [Architecture in Ploești, historical study] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Cartea Românească. 16725..[18] The book contains many of the chapters written (by the architect) for Ploești's monograph by Mihail Sevastos.

- (in Romanian) Sevastos, Mihail (1937). Monografia orașului Ploești [Monograph of the city of Ploești] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Cartea Românească..[19]

- (in Romanian) Petrescu, Gabriela (2024). ARHITECȚII SOCOLESCU 1840-1940, Studiu monografic [SOCOLESCU ARCHITECTS 1840-1940, Monographic study] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Simetria. ISBN 978-973-1872-55-1.[20]

- (in Romanian) Lucian Vasile, historian, expert and head of office at the Institute for the Investigation of the Crimes of Communism and the Memory of Romanian Exile, President of the Association for Education and Urban Development (AEDU),[21][22] author of the specialized site on the city of Ploiești and its history: RepublicaPloiesti.net.

- (in Romanian) Vasile, Lucian (2016). Orașul sacrificat. Al Doilea Război Mondial la Ploiești [The sacrificed city. World War II in Ploiești] (in Romanian) (2nd ed.). Ploiești: Asociatia pentru Educatie si Dezvoltare Urbana. ISBN 978-973-0-21379-9..[23]

External links

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- (a) Socolescu, Toma T. (1938). "prefaced by Nicolae Iorga". Arhitectura în Ploești, studiu istoric [Architecture in Ploești, historical study] (in Romanian). București: Cartea Românească. 16725.

- ^ a b c p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j p. 47.

- ^ pp. 37, 47, 48 and 105.

- ^ p. 105.

- ^ translation of an extract from page 37.

- ^ pp. 105-106.

- ^ a b c p. 48.

- ^ pp. 14 and 47.

- ^ p. 41.

- ^ pp. 37-38.

- ^ pp. 44-45 (photograph of the time) and 47.

- ^ a b pp. 42-43.

- ^ Note 5, pp. 46-47.

- ^ pp. 42-43 and 46.

- ^ p. 42.

- ^ pp. 32-33.

- ^ page 1 "CUVÂNT INTRODUCTIV", the book is also regularly annotated with local archive sources on which the author relies.

- ^ pp. 43 and 47.

- ^ pp. 47 and 104.

- ^ pp. 51-52.

- ^ Comparison with its photograph available on page 52, also published in this article.

- (b) Socolescu, Toma T. (2004). Amintiri [Memories] (in Romanian). București: Editura Caligraf Design. ISBN 973-86771-0-6.

- ^ pp. 14-15.

- ^ Note 8 - p. 15.

- ^ a b pp. 8-9 - Extract from the ennoblement deed of July 14, 1655.

- ^ p. 14 - Toma T. Socolescu writes:

"My grandfather, Nicolae Gh. Socolescu, also an architect, having finished his studies in Vienna, was a descendant of a family that, through a distant ancestor, had obtained a noble rank, in 1655, from G. Rakoczy. The original document written in calfskin, in Latin, with gold letters and the family emblem in colors, laced and bearing the princely seal in red wax, is in the possession of Major S. Socol, former mayor of the city of Făgăraș, where he lives." (Translated from Romanian)

- ^ p. 14 - Toma T. Socolescu writes:

"N. G. Socolescu (Socol, in Ardeal) came to Muntenia from the Berivoiul Mare commune, located at the foot of the mountains in the Făgăraș region, and settled in Ploiesti, together with his five other brothers, - around the revolution, around 1846, - namely in Sf. Spiridon outskirts. During my childhood and until later, there was his house in Culea Căleni, a ground-floor house, square-shaped, set back from the street and surrounded by a garden. He married Ioana, born Săndulescu, from the same suburb, and his name appears among the founders in the parish registers; and as was customary at the time, I believe he was also buried there - although the searches I made were unsuccessful - in 1872." (Translated from Romanian)

- ^ p. 15.

- (c) Socolescu, [Toma T. (2004). Fresca arhitecților care au lucrat în România în epoca modernă 1800 - 1925 [Fresco of architects who worked in Romania in the modern era 1800 - 1925.] (in Romanian). București: Editura Caligraf Design. ISBN 973-86771-1-4.

- (d) Sevastos, Mihail (1937). Monografia orașului Ploești [Monograph of the city of Ploești] (in Romanian). București: Cartea Românească.

- ^ a b c p. 177.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j p. 187.

- ^ pp. 138, 177, 187 and 214.

- ^ p. 214.

- ^ pp. 214-215.

- ^ a b c p. 188.

- ^ pp. 154 and 187.

- ^ p. 761.

- ^ p. 181.

- ^ pp. 177-178.

- ^ page 431: Biography of the politician; p. 422: 'The Mayors's Gallery'.

- ^ pp. 136-137. A humanist doctor who cared for the poor and unfortunate in hospital and devoted his time to the commun good, he was also a member of parliament, a prefect and a member of a parliamentary reform commission.

- ^ pp. 184-185 and 187.

- ^ a b pp. 182-183.

- ^ Note 5, pp. 186-187.

- ^ pp. 182-183 and 186.

- ^ p. 182.

- ^ pp. 172-173.

- ^ pp. 183 and 187.

- ^ pp. 187 and 213.

- ^ pp. 191-192.

- ^ Comparison with its photograph available on page 192, also published in this article.

- (e) Petrescu, Gabriela (2024). ARHITECȚII SOCOLESCU 1840-1940, Studiu monografic [Solescu Architects 1840-1940, Monographic Study] (in Romanian). București: Editura Simetria. ISBN 978-973-1872-55-1.

- ^ p.19.

- ^ p. 17 - Papazoglu, Dimitrie (2005). Istoria fondărei orașului București [History of the foundation of Bucharest] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Curtea Veche. p. 59. ISBN 973-669-107-1.

- ^ translation from Romanian of extracts from passages quoted on page 17 - Stan, Constantin (1928). Şcoala poporană din Făgăraş şi depe Târnave, Volumul I, Făgăraşul [People's school in Făgăraș and on the Târnave, Vol I, Făgăraşul] (in Romanian). Sibiu: Tiparul institutului de arte Grafice “Dacia Traiană”. pp. 150–152.

- ^ p. 18.

- ^ p. 20 -

(Translated from Romanian).Foreign architects, engineers and craftsmen played an important role in the Principality's modernization history.

Among the few Romanian architects active in the first half of the 19th century were: in Moldova, Gh. and D. Asachi, Al. Costinescu, and in Muntenia, Nicolae G. Socolescu, à Ploiești, Jupân Ioniță and Vitul in Bucharest, Alexandru Orăscu, with studies in Berlin and Munich. In 1843, the architect of the city of Ploiești was the Swiss Johann Schlatter, and in 1847, the city's architect was the Austrian Karl Hartel, the author of the first building of the courthouse, police and fire department pavilion, designed in neoclassical style. - ^ a b p. 21.

- ^ a b c p. 25.

- ^ p. 20.

- ^ pp. 19-25.

- ^ pp. 19-21.

- ^ p. 14.

- ^ pp. 20, 22 and 25.

- (f) Vasile, Lucian (August 2009). "RepublicaPloiesti.net". Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești.

- ^ Vasile, Lucian (September 2012). "Hotel Europa". Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Vasile, Lucian (August 2009). "Cladirile Primariei din Ploiesti" [Ploiesti City Hall buildings]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ History and photographs: Vasile, Lucian (January 2022). "Care-i treaba cu blocul "7 etaje"?" [What about the “7 stage” block?]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Hotel Carol history: Vasile, Lucian (January 2011). "Palatul Telefoanelor" [The Telephone Palace]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- Additional information and photographs on the following pages:

- Vasile, Lucian (June 2016). "Top 10 clădiri dispărute ale orașului Ploiești" [Top 10 missing buildings of Ploiești]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- Carol history: Vasile, Lucian (October 2020). "Cât costa o cameră la hotelurile din Ploiești în 1934?" [How much did a hotel room in Ploiesti cost in 1934?]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- Carol history: Vasile, Lucian (September 2012). "Hotel Europa". Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024..

- ^ Photographs and history of the Rășcan house degradation: Vasile, Lucian (March 2013). "Inapoi pe Calea Campinii" [Back to Calea Campinii]. Republica Ploiesti - Povești despre vechiul Ploiești (in Romanian). Ploiești. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- Other notes and references :

- ^ Predescu, L. (1940). fr:Enciclopedia Cugetarea [Cugetarea Enciclopedy] (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Cugetarea – Georgescu Delafras. pp. 792–793.

- ^ (in Romanian) Article Mihai Viteazul, Enciclopedia României - Mihai Viteazul, Origin and family.

- ^ Slavonic inscription on the cross on the tombstone of Răzvadu de Sus: " Died, the servant of God Marula, Master of the Royal Court, Lady of Messire Socol, former Grand Master of the Royal Court, daughter of the late Prince Mihai and Lady Tudora, in the year 1647, during the reign of Prince Ion Matei Basarab in 17 December, around the tenth hour of the night, solar calendar of the 21st year ", according to the Romanian translation done by G.D Florescu in 1944 from an original slave version:

" A răposat roaba lui Dumnezeu Marula clucereasa jupanului Socol fost mare clucer, fiică a răposatului Io Mihai Voevod și a jupînesei Tudora la anul 1647 în zilele lui Ion Matei Basarab voevod în luna decembrie 17 zile spre al zecilea ceas din noapte crugul solar temelia 21 ".

(in Romanian) Source: G.D. Florescu, Idem, Un sfetnic al lui Matei Basarab, ginerele lui Mihai Viteazul, in Revista istorică română, XI–XII, 1941–1942, pp. 88–89. - ^ Moldovan, Horia (2013). Johann Schlatter : cultură occidentală şi arhitectură românească (1831-1866) [occidental culture and Romanian architecture (1831-1866)] (in Romanian). Rennes: Simetria. ISBN 978-973-1872-26-1. - Available at the Ion Mincu University of Architecture library under reference 'III 5369' Direct link.

- ^ Alexandru G. Radovici mayor of Ploiești from May 1898 to May 1899, then president of the interim commission from February to April 1901; Ion N. Radovici from June 1876 to June 1877.

- ^ a b c d e Which became Bulevard Republicii

- ^ Building photographs just after the American bombings of 1944: Vasile, Lucian (2014). Orașul sacrificat. Al Doilea Război Mondial la Ploiești [The sacrificed city. World War II in Ploiești] (in Romanian) (1st ed.). Ploiești: Asociatia pentru Educatie si Dezvoltare Urbana. p. 336. ISBN 978-973-0-21379-9.

- ^ translation: Architecture in Ploiești, historical study.

- ^ then called Telegii Alley, and later I.C Brătianu.

- ^ History and photographs on the Câmpina TV website: "Câmpina, România 100. Casa Carcalechi, de ieri, primul sediu al Primăriei Câmpina, aceeaşi zonă în zilele noastre" [Câmpina, Romania 100. Casa Carcalechi, from yesterday, the first Câmpina City Hall building, same area today]. Câmpina TV (in Romanian). October 14, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Information and photographs on the Câmpina TV website: "S-a întâmplat în Câmpina, de-a lungul timpului, la data de 17 octombrie" [It happened in Câmpina, over time, on October 17]. Câmpina TV (in Romanian). Câmpina. October 17, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2024. And "Câmpina, România 100. Primăria din perioada interbelică, blocurile de astăzi" [Câmpina, Romania 100. Interwar town hall, today's blocks]. Câmpina TV (in Romanian). Câmpina. October 13, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2024. Other information on the Câmpina town hall website - Town Hall photograph after 1922.

- ^ Toma T. Socolescu has written a reference work on the architects who worked in Romania from 1800 to 1925: Fresca arhitecților care au lucrat în România în epoca modernă 1800 - 1925

- ^ Translated from Romanian.

- ^ in 2024.

- ^ See Gabriela Petrescu's article: Ion N. Socolescu.

- ^ The work is available for consultation:

- (in Romanian) at "Nicolae Iorga" County Library in Ploiești on Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova catalog, reference cota topografica 'DIV 919'.

- (in Romanian) at the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urban Planning - Library website: Direct link, on BUAUIM catalog, reference 'III 5037'.

- (in Romanian) at the Romanian National Library on BNR catalog, reference 'IV 71751'.

at the Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg on BNU Strasbourg catalog, reference 'BH.32.336'.

at the Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg on BNU Strasbourg catalog, reference 'BH.32.336'.

- ^ The work is available for consultation:

- (in Romanian) at "Nicolae Iorga" County Library in Ploiești on Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova catalog, reference cota topografica 'DIV 918'.

- (in Romanian) at the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urban Planning - Library website: Direct link, on BUAUIM catalog, references 'III 5036' and 'III 2892' for the 1955 copy.

- (in Romanian) at the Bucharest Carol I Central University Library. (Biblioteca Centrală Universitară Carol I), on BCUB catalog, reference 'IV518874'.

- (in Romanian) at the Romanian National Library on BNR catalog, reference 'IV 71752'.

at the British Library on BL catalog, reference 'YF.2006.b.1101'.

at the British Library on BL catalog, reference 'YF.2006.b.1101'.

- ^ The book is available:

- (in Romanian) at "Nicolae Iorga" County Library in Ploiești on Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova catalog, reference cota topografica 'ADIV 836'.

at the "Bibliothèque nationale de France" on BnF catalog, reference 'notice FRBNF31380368'.

at the "Bibliothèque nationale de France" on BnF catalog, reference 'notice FRBNF31380368'.

- ^ The monograph is available:

- (in Romanian) at "Nicolae Iorga" County Library in Ploiești on Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova catalog, reference cota topografica 'DV 87', and also in a newer 2002 edition, reference cota topografica 'ADV 661'.

- (in Romanian) at the Bucharest Carol I Central University Library. (Biblioteca Centrală Universitară Carol I), on BCUB catalog, reference '65293'.

- (in Romanian) as well as at the Romanian Academy Library on AR catalog, reference 'III 814535'.

- ^ The book is available:

- (in Romanian) at the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urban Planning - Library website: Direct link, on BUAUIM catalog, reference 'II 8867'.

- (in Romanian) at the Romanian National Library on BNR catalog, reference 'IV 120354'.

- ^ (in Romanian) Asociația pentru Educație și Dezvoltare Urbană.

- ^ (in Romanian) CV de Lucian Vasile.

- ^ The book is available:

- (in Romanian) at "Nicolae Iorga" County Library in Ploiești on Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova catalog, reference cota topografica 'AII 77997' (2014 edition).

- (in Romanian) at the Bibliothèque du județ "Nicolae Iorga" à Ploiești sur le catalogue de la Biblioteca Judeteana "Nicolae Iorga" Prahova, sous la référence

- (in Romanian) at the Bucharest Carol I Central University Library. (Biblioteca Centrală Universitară Carol I), on BCUB catalog, references 'II332442' and '87382'.

- (in Romanian) at the Romanian National Library on BNR catalog, reference 'II 628139'.

- (in Romanian) as well as at the Romanian Academy Library on AR catalog, reference 'II 993585' and 'II 1043915'.

at the British Library on BL catalog, reference 'YF.2018.a.3147'.

at the British Library on BL catalog, reference 'YF.2018.a.3147'.