Battle of Montgomery's Tavern

| Battle of Montgomery's Tavern | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Upper Canada Rebellion and the Rebellions of 1837–1838 | |||||||

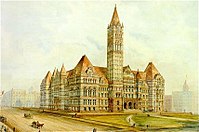

Depiction of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Opposition rebels |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Anthony Van Egmond | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 210 militia |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Official name | Montgomery's Tavern National Historic Site of Canada | ||||||

| Designated | 1925 | ||||||

| History of Toronto | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Events | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Other | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Montgomery's Tavern was an engagement which took place on December 7, 1837 during the Upper Canada Rebellion. The abortive revolutionary insurrection, inspired by William Lyon Mackenzie, was crushed by British authorities and Canadian volunteer units near John Montgomery's tavern on Yonge Street at Eglinton, north of Toronto.

The site of Montgomery's Tavern was designated a National Historic Site in 1925[1][2] and a historical marker sits at the south-west corner of Yonge Street and Broadway Avenue.

Background

[edit]In 1835, Sir Francis Bond Head was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. The reformers of Upper Canada initially believed that he would support restructuring the governance system of the province.[3] However, Bond Head believed the reformers were disloyal to the British Empire, and he supported the Family Compact. Bond Head called an election in 1836[4] and campaigned for Tory candidates.[5] Many reform candidates lost their seats, and the new Tory-dominated legislature passed legislation that entrenched their power or supported their business enterprises.[6]

When the Lower Canada Rebellion broke out in the fall of 1837, Bond Head sent the British troops stationed in Toronto to help suppress it. William Lyon Mackenzie was sent by rebel leaders into communities north of Toronto to gauge support for a rebellion. He organized militias and upon his return to Toronto informed rebel leaders that the rebellion would begin on December 7, 1837.[7]

Anthony Anderson and Samuel Lount were commanders of the forces gathered at Montgomery's Tavern.[7] While on a scouting mission, Mackenzie, Anderson and other rebels encountered John Powell.[8] While attempting to take them prisoner, Powell shot Anderson and escaped to Toronto.[9] Lount refused to command the rebels by himself, so the leadership decided that Mackenzie would be the commander.[10]

On December 5, Allan MacNab arrived in Toronto with sixty men from the Hamilton area. MacNab was named commander-in-chief and leader of the battle against the rebels by Bond Head.[11] At a council-of-war meeting on December 6, James FitzGibbon was furious at this appointment because he felt he was the best person for the role, and he left the meeting early. The meeting decided to attack the rebels the next day, and MacNab informed FitzGibbon that he had resigned as the leader so FitzGibbon could take the role.[12]

Prelude

[edit]FitzGibbon organized the government's forces for an attack on the rebels. The government forces had 1,200 men and two cannons, and Bond Head ordered that they march towards Montgomery's Tavern at noon on 7 December 1837.[13] FitzGibbon sent two detachments ahead of the group to march several hundred yards away from either side of Yonge Street. The rest of the army marched up the street.[14]

Anthony Van Egmond arrived at the tavern on December 7 expecting to command a well-armed rebel force. When he saw the poorly equipped militia, he proposed defending their position until reinforcements arrived from the rural areas of Upper Canada. Mackenzie demanded that Egmond plan to attack the government troops instead and the rebel leaders decided to send 60 riflemen to the Don Bridge to divert the government troops if they arrived from that path.[13]

Battle

[edit]A sentinel of the rebels saw the government's troops approach the tavern from Gallows Hill.[15] One hundred and fifty men were posted in the woods approximately a half-mile south of the tavern on the west side of Yonge Street. Several dozen took up positions behind stump fences on the east side of Yonge Street. The rest of the rebels were at the tavern without arms.[14]

When the government forces arrived the rebels fired upon them. FitzGibbon split the militias at the front of the group into two sections to continue their march. Major Carfrae turned his artillery and fired upon the rebels. The western detachment that had been sent ahead earlier that day attacked the rebels, who fled towards the tavern. The government army's march continued to Montgomery's tavern. A cannonball shot through the dining room window and the rebels in the tavern fled. When Bond Head arrived at the tavern he ordered that it be burned down.[14]

Sir John A. Macdonald served as a Private in the Commercial Bank Guard on active duty in Toronto guarding the Commercial Bank of the Midland District on King Street. The company was present at Montgomery's Tavern and Macdonald recalled in an 1887 letter to Sir James Gowan that:

"I was in the Second or Third Company behind the cannon that opened out on Montgomery’s House. During the week of the rebellion I was [in] the Commercial Bank Guard in the house on King Street, afterward the habitat of George Brown’s 'Globe'."[16]

Aftermath

[edit]

The rebels fled to the United States, travelling in groups of two.[14] Van Egmond and Lount were captured by British forces; the former died of an illness he received while imprisoned and the latter was hanged for treason. Other men were also sentenced to hang for treason and ninety-two men were sent to Van Diemen's Land.[17] A group of rebels escaped Fort Henry and travelled to the United States.[18]

Following the rebellion, the site of the tavern was used to build a hotel, with the structure of the old Davisville Hotel.[19] In 1858 it was sold to hotelier Charles McBride of Willowdale, who renamed the tavern Prospect House.[20] The tavern would serve as Masonic Lodge and North Toronto township council office. McBride sold the hotel in 1873 to build another hotel, Bedford Park Hotel, on Yonge Street. Prospect House burned down in 1881, and the vacant land was sold to the proprietor (and later as a hotelier) John Oulcott of Toronto, who rebuilt a three-storey Oulcott's Hotel (Eglinton House) in 1883.[21] Oulcott sold out in 1912 and the hotel went to various owners.

In 1913, the federal government purchased the hotel and remodelled it as a post office for the North Toronto postal district.[22] It was torn down in the 1930s and replaced by the current structure.[21] The site of the tavern is now occupied by a two-storey Art Deco post office designed by Murray Brown and built in 1936. The building, known as Postal Station K, bears the cypher EviiiR for Edward VIII, who reigned as king for eleven months in 1936. It is one of the few buildings to bear this mark in Toronto.[citation needed]

As of spring 2016, construction is underway to incorporate the former post office building into a new structure that will include retail space and a podium for the 27-storey Montgomery Square luxury rental apartment tower.[needs update]

References

[edit]- ^ "Montgomery's Tavern National Historic Site of Canada". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved December 8, 2018., Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada.

- ^ Montgomery's Tavern. Canadian Register of Historic Places.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 161.

- ^ Craig 1963, pp. 232–238.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 173.

- ^ Schrauwers 2009, pp. 184–191.

- ^ a b Kilbourn 2008, p. 194.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 203.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 204.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 206.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 216.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 220.

- ^ a b Kilbourn 2008, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d Kilbourn 2008, p. 223.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 222.

- ^ Johnson, J.K. (1968). The Papers of the Prime Ministers, Volume 1: The Letters of Sir John A. Macdonald, 1836-1857. Ottawa: Public Library of Canada.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 231.

- ^ Kilbourn 2008, p. 244.

- ^ Jackes, p. 11.

- ^ Mulvany & Adam 1885, p. 229 229.

- ^ a b Berchem 1996, p. 91.

- ^ "North Toronto's New Post Office". The Toronto World. September 8, 1913. p. 3. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

Works cited

[edit]- Berchem, F.R. (1996). Opportunity Road: Yonge Street 1860–1939. Toronto: Natural Heritage/Natural History. ISBN 978-1-4597-1337-6. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- Craig, Gerald (1963). Upper Canada: The Formative Years 1784–1841. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Jackes, Lyman B. "The Building That Rose From the Ruins of the Famous Montgomery's Tavern". Tales of north Toronto. Vol. 2. Toronto: Canadian Historical Press. p. 11.

- Kilbourn, William (2008). The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-77-070324-7. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- Mulvany, Charles Pelham; Adam, Graeme Mercer (1885). History of Toronto and county of York, Ontario. C.B. Robinson. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- Read, David Breakenridge (1896). The Canadian Rebellion of 1837. Toronto: C.B. Robinson.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength: W.L. Mackenzie, the Children of Peace, and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9927-3. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Wrong, George M.; Langton, H. H. (2009). The Chronicles of Canada: Volume VII – The Struggle for Political Freedom. Fireship Press. ISBN 978-1-934757-50-5. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Upper Canada, The Confrontation at Montgomery's Tavern

- Colonel Moodie Rides Down Yonge Street

- Statement of proceedings in Toronto against MacKenzie's mob of assassins, prepared for the Upper Canada Herald by three gentlemen who were eye-witnesses, 1837

- Review of Mackenzie's publications on the revolt before Toronto, in Upper Canada, 1838