Space Jam

| Space Jam | |

|---|---|

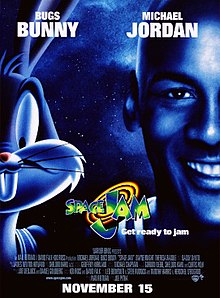

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joe Pytka |

| Written by | |

| Based on | Looney Tunes by Warner Bros. |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by | Sheldon Kahn |

| Music by | James Newton Howard |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $80 million[3] |

| Box office | $250.2 million[4] |

Space Jam is a 1996 American live-action/animated sports comedy film directed by Joe Pytka and written by Leo Benvenuti, Steve Rudnick, Timothy Harris, and Herschel Weingrod. The film stars basketball player Michael Jordan as a fictional version of himself; the live-action cast also includes Wayne Knight and Theresa Randle, as well as cameos by Bill Murray and several NBA players, while Billy West, Dee Bradley Baker, Kath Soucie and Danny DeVito headline the voice cast. The film follows Jordan as he is brought out of retirement by the Looney Tunes characters to help them win a basketball match against invading aliens intent on enslaving them as amusement park attractions.

Space Jam was the first film to be produced by Warner Bros. Feature Animation and was released theatrically in the United States on November 15, 1996, by Warner Bros. under its Family Entertainment label.[1] Critics were divided over its premise of combining Jordan and his profession with the Looney Tunes characters, while praising the technical achievements of its intertwining of live-action and animation.[5] It was a commercial success, grossing over $250 million worldwide to become the highest-grossing basketball film of all time until 2022, as well the tenth-highest-grossing film of 1996.

A standalone sequel, Space Jam: A New Legacy, was released in 2021, with LeBron James in the lead role. The sequel failed to match the commercial success of the first film and received generally negative reviews.

Plot

[edit]In 1973, a young Michael Jordan tells his father, James, about his dreams of playing in the NBA. Twenty years later, following James’ death, Jordan retires from basketball to pursue a career in baseball.

In outer space, amusement park Moron Mountain is in decline. Its proprietor, Mr. Swackhammer, learns of the Looney Tunes from the Nerdlucks, his quintet of alien minions, and orders them to abduct the Tunes to serve as attractions. The Nerdlucks enter the Tunes' universe hidden in the center of the Earth through a parking lot of a Piggly Wiggly and hold them hostage before Bugs Bunny convinces them to allow the Tunes to defend themselves. Tunes challenge the Nerdlucks to a basketball game, noting the latter's small stature. After seeing a documentary about basketball, the Nerdlucks infiltrate various NBA games, stealing the talents of Charles Barkley, Shawn Bradley, Patrick Ewing, Larry Johnson, and Muggsy Bogues. They use these talents to transform into gigantic, muscular versions of themselves known as the "Monstars".

Realizing they need help, the Looney Tunes pull Jordan into their universe as he golfs with Bill Murray, Larry Bird, and Jordan's assistant, Stan Podolak, where Bugs explains their situation to Jordan. However, Jordan is initially reluctant to help, but later agrees after a confrontation with the Monstars, and forms the "Tune Squad” with the Tunes; they are joined by Lola Bunny, with whom Bugs is enamored. Jordan is initially unprepared, and sends Bugs and Daffy Duck to his house in the live-action world to obtain his basketball gear. Jordan's children aid them and agree to keep the game a secret, while Stan, searching for Jordan, notices Bugs and Daffy, follows them to their world, and joins the team. Meanwhile, the incapacity of the five players results in a nationwide panic that culminates in the season's suspension. The players try to restore their skills through various methods, with no success.

The game between the Tune Squad and the Monstars commences, with Swackhammer arriving to observe. The Monstars dominate the first half, lowering the Tune Squad's morale. During halftime, Stan surreptitiously learns how the Monstars obtained their talent and informs the Tune Squad. Disguising a bottle of water as "secret stuff", Bugs and Jordan motivate the Tune Squad, who improve in the second half using their cartoon physics. During a time-out, Jordan raises the stakes with Swackhammer: if the Tune Squad wins, the Monstars must relinquish their stolen talent, and if the Monstars win, Jordan will spend the rest of his life being Moron Mountain's newest attraction. On Swackhammer's orders, the Monstars become increasingly violent, injuring most of the Tune Squad.

With ten seconds left in the game, the Tune Squad is down by one point and one player, with only Jordan, Bugs, Lola, and Daffy still able to play. Murray unexpectedly arrives and joins the team. In the final seconds, Jordan gains the ball with Murray's assistance but is pulled back by the Monstars. On Bugs' advice, Jordan uses cartoon physics to extend his arm and achieve a slam dunk, winning the game with a buzzer beater. After Swackhammer scolds the Monstars for their failure, Jordan helps them realize that they only served him because they were once smaller. Having had enough of their boss's behavior towards them, the Monstars insert Swackhammer inside a missile that sends him to the moon. After relinquishing their stolen talent, the Nerdlucks decide to join the Tunes, while Jordan and Stan return to Earth and return the talent to the five players, whose remarks convince Jordan to return to the NBA.

Cast

[edit]Live-action

[edit]- Michael Jordan as himself[6]

- Wayne Knight as Stan Podolak, a publicist and assistant who aids Jordan[6]

- Theresa Randle as Juanita Jordan, Jordan's wife

- Charles Barkley as himself[6]

- Muggsy Bogues as himself[6]

- Shawn Bradley as himself

- Patrick Ewing as himself[6]

- Larry Johnson as himself

Space Jam's cast includes Manner Washington, Eric Gordon, and Penny Bae Bridges as Jordan's children, Jeffrey, Marcus, and Jasmine, respectively. Brandon Hammond plays the ten-year-old Michael Jordan. Larry Bird and Bill Murray appear as themselves,[6] and Thom Barry portrays Jordan's father, James R. Jordan Sr. Several NBA players make cameo appearances in Space Jam, including Danny Ainge, Steve Kerr, Alonzo Mourning, Horace Grant, A.C. Green, Charles Oakley, Luc Longley, Cedric Ceballos, Derek Harper, Vlade Divac, Brian Shaw, Jeff Malone, Bill Wennington, Anthony Miller, and Sharone Wright, as do coaches Del Harris and Paul Westphal, and broadcasters Ahmad Rashad and Jim Rome. Dan Castellaneta and Patricia Heaton cameo as fans at a game between the New York Knicks and Phoenix Suns.

Voice cast

[edit]- Billy West as Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd

- Dee Bradley Baker as Daffy Duck, Tasmanian Devil, and Bull

- Danny DeVito as Swackhammer, the proprietor of Moron Mountain, an intergalactic amusement park[6]

- Bob Bergen as Porky Pig, Tweety, Marvin the Martian, Barnyard Dawg, Hubie and Bertie[7]

- Bill Farmer as Sylvester, Yosemite Sam, and Foghorn Leghorn

- Maurice LaMarche as Pepé Le Pew

- June Foray as Granny

- Paul Julian as the Road Runner (archive recordings) (uncredited)

- Kath Soucie as Lola Bunny

The Nerdluck voices include Jocelyn Blue as their orange leader, Pound, Charity James as the dim-witted blue Blanko, June Melby as the neurotic green second-in-command Bang, Colleen Wainwright as the diminutive red Nawt, and producer Ivan Reitman's daughter, Catherine, as the eccentric purple Bupkus. Their transformed "Monstar" versions are voiced by Darnell Suttles (Pound), Steve Kehela (Blanko), Joey Camen (Bang), Dorian Harewood (Bupkus), and T.K. Carter (Nawt). Wainwright also voices Sniffles, Kehela also voices Bertie's announcer voice, and Frank Welker voices Jordan's bulldog, Charles.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

In 1992 and 1993, two Super Bowl Nike ads, "Hare Jordan" and "Aerospace Jordan" respectively, aired on television and featured Michael Jordan with the character Bugs Bunny.[3][8] Wieden+Kennedy creative director Jim Riswold conceived the "Hare Jordan" campaign following the popularity of advertisements where Jordan played with Mars Blackmon (played by Spike Lee), a character from She's Gotta Have It (1986); he chose Bugs Bunny for his next campaign because the character was his "childhood hero".[3] Directed by Joe Pytka, "Hare Jordan" took six months and a $1 million budget to make.[3] It was hindered by reluctance from Warner Bros. to allow Nike to modernize Bugs' character; however, the commercial success of both ads "was a nice bit of research for Warner Bros. to understand that the Bugs character still had relevance and to tie it in with Michael", explained Pytka.[9] This led to the company green-lighting a film featuring Jordan and Bugs, which came out of a plane meeting between a Nike executive and producer Ivan Reitman.[8][3] Jordan was offered movie deals previously, but his manager, David Falk, turned them all down because he felt the basketball icon could only act as himself.[3]

The project was closed when Jordan retired from basketball in 1993, only to be reopened in 1995 when Jordan returned as a basketball player.[10] Falk pitched the idea to several major studios, without a story or script written.[3] One of them was Warner Bros., which tried to create more "adult, sophisticated material" that deviated from the formula set by Disney in the animated film market.[11] After Warner Bros. initially rejected Falk's pitch, he called the consumer products division leader, Dan Romanelli, reacting in surprise the studio would turn down a project having potential of high-selling merchandise.[3]

Pytka was informed about the project only months before the start of principal photography; in addition to being hired as director, he also revised the script, including writing a scene where Jordan hits a home run after he returns to Earth that was filmed, but ultimately never used.[9] Spike Lee was also interested in helping Pytka with the screenplay, but Warner Bros. blocked him from the project out of dissatisfaction from how he funded Malcolm X (1992).[9]

Casting

[edit]According to Pytka, it was difficult to get most actors involved with Space Jam due to its odd premise: "I mean, they're going to work with an animated character and an athlete — are you serious? They just didn't want to do it."[9] Before Wayne Knight was cast as Stan, his initial choices were Michael J. Fox and Chevy Chase, whom he had worked with on Doritos commercials; Warner Bros. rejected both actors.[9] Jason Alexander also turned down the role.[12] The easiest actors to obtain were the NBA players, except for Gheorghe Mureșan.[9] Bill Murray's appearance was present in the script from the beginning, but the filmmakers were unable to book him until filming started; there are rumors that Jordan begged Murray to be in the film.[13]

Reitman, serious about the voice actors for the established Looney Tunes characters being far better than their original voice actor, Mel Blanc, and not just replications, was very involved in the voice casting.[14] Joe Alaskey, one of Blanc's successors since the latter's death, was put by Reitman through a set of auditions, which lasted for months until Alaskey grew tired of auditioning and backed out from the project.[15] Billy West learned of Space Jam through Reitman on The Howard Stern Show, who was producing Stern's film, Private Parts. Reitman was impressed by West's voice talent and asked him if he could audition for Space Jam. West accepted, and after doing an audition, he landed the roles of Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd.[16] The casting directors originally planned several voice cameos; however, that did not work out, and Danny DeVito ended up being the only celebrity voice actor in the film, which was for Mr. Swackhammer, who was originally planned to be played by Jack Palance.[14] Swackhammer was also planned to be a live-action character until the very final days of development, with Dennis Hopper possibly playing the role due to his friendship with Pytka.[11]

One thing I heard was that Ivan Reitman, when they were thinking about going ahead with this movie, had phoned up Robert Zemeckis about Who Framed Roger Rabbit and asked, "Do you have any advice on what we should do to make a movie like this?" And he said, "Don't do it, it nearly killed me."

— Neil Boyle, supervising animator[11]

Scale

[edit]The Classic Animation faction of Warner Bros., which animated the commercials and was located in Sherman Oaks, Los Angeles, was originally planned to be the only company responsible for Space Jam. However, after only a week, the animation work was so complicated that Warner Bros. contacted more studios, including reassigning the Feature Animation division in Glendale from working on Quest for Camelot (1998) to Space Jam. Ten of Classic Animation's members, including the production's animation director Tony Cervone, were taken out of the faction to become involved all throughout production, and development artists were reassigned to animating jobs, including supervising animator Bruce Woodside, who had little faith in the project: "Like so many other animators, I adore the classic Warner Bros. characters, but I really had little hope that tying them to the massive anchor of an apparently doomed marketing scheme could actually give them a successful second life in features".[11]

After Cervone was hired as animation director, Jerry Rees contacted Bruce W. Smith about being another animation director on the film; Rees was fired by the time Smith joined, and Pytka hired Smith to direct the animation sequences alongside Cervone.[11] Before January 1996, when animation production was put into overdrive, none of the animators' drafts or concepts for how the film should look met with Reitman's approval;[17] Bill Perkins joined that month as animation art director, and when first arriving at the Sherman Oaks division, "we only had around eight months to do about 52 minutes of animation" and "it was just kind of a little skeleton crew."[11] Cervone highlighted Reitman's role as supervisor: "It started off as a string of gags with no structure, and he helped a lot with that."[18] The drafting process involved the animators and artists using the original cartoons as references.[17] Ultimately, they went with Bob Clampett's style of animation due to being wilder than Chuck Jones' style.[19]

Production of Space Jam totaled around 19 months, with filming taking up ten of them;[11] this was half the time of any other film of its kind according to Smith.[20] The animation was done at a very quick pace by more than 700 workers from 18 studios in London, Canada, California and Ohio,[11][20] starting January 1996 by the recently joined producers Ron Tippe and Allison Abbate.[21] In trying to track the huge amount work done at the 18 studios, Tippe hung stills of all the shots throughout the Feature Animation faction's hallways, with completed ones marked in red.[22]

Features about the film's production, including one from the official website, emphasized its state-of-the art computer technology when it came to its live-action/animation hybrid; "this film could have not been made two years ago," claimed Cervone in 1996.[17] Due to its mixture of various art mediums as well as the "broad sense of humor and entertainment" unique to the Looney Tunes, Smith considered Space Jam an important part of diversifying the animation industry.[23] Space Jam broke the record for amount of composited shots in a featured film,[24] "roughly 1,043" according to Tippe,[10] as well as a record number of FX shots, with around 1,100 in a single 90-minute film; Independence Day (1996), released the same year, had 700 FX shots within two hours of screen time.[8] Tippe claimed the film would have, at most, "multiple characters, multiple levels of effects and, in some cases, up to 70 elements" in one shot.[25]

Filming

[edit]Space Jam was one of the first-ever productions to be shot on a virtual studio.[11] Jordan filmed in a 360-degree green screen room with motion trackers; around him were green-suited NBA players and improv actors from the Groundlings Theatre and School serving as placement identifiers for the animated characters, with a CGI background replica of a real-life setting chroma-keyed in.[11][26][17] Although Bill Murray initially came in only to work on the golf course scene, he then wanted to be in the climactic basketball game after Pytka showed him the process of how he directed the live-action/animation scenes.[9]

Concept drawings and discussions between the animators and Pytka about how the animation would be incorporated into the live-action shots took place on set during shooting, and re-writes to the script would be done daily.[11] As an experienced commercial and music video director working on a sports film, Pytka took on fast, unlimited camera movements and Dutch angles;[17][11] this made integrating the characters into the shots challenging for the animators.[17] To connect the real and animated worlds together, blue-screen shots of miniatures by Vision Crew Unlimited were used; these include a Christo-inspired interpretation of The Forum arena for exterior shots, city rooftops for a transition scene with a wide skyline view of Chicago serving as the chroma-keyed background,[27] and space ship parts initially produced by Boss Film Studios for a Philip Morris advertisement.[22]

Music

[edit]The soundtrack sold enough albums to be certified as 6-times Platinum.[28] The song "I Believe I Can Fly" by musical artist R. Kelly earned him three Grammy Awards.[29] Other tracks included a cover of Steve Miller Band's "Fly Like an Eagle" (by Seal), "Hit 'Em High (The Monstars' Anthem)" (by B-Real, Busta Rhymes, Coolio, LL Cool J, and Method Man), "Basketball Jones" (by Barry White & Chris Rock), "Pump up the Jam" (by Technotronic), "I Turn to You" (by All-4-One) and "For You I Will" (by Monica). The film's title song was performed by the Quad City DJ's.

There was also an original scoring soundtrack featuring most of James Newton Howard's score from the film, except the main Merrie Melodies Theme itself.

Coincidentally, Biz Markie, who was a guest vocalist on the Spin Doctors's cover of KC and the Sunshine Band's "That's the Way (I Like It)" on the soundtrack died from complications from type 2 diabetes on the release date of the sequel.[30]

Animation and design

[edit]Technology

[edit]Space Jam was one of the earliest animated productions to use digital technology. 2D animation and backgrounds were first done on paper with pencil at the Sherman Oaks studio before being scanned into Silicon Graphics Image files through Cambridge Animation Systems' software Animo and were then sent to Cinesite via a File Transfer Protocol, for its team to touch upon, digitally color, and composite into shots in Photoshop before being sent back to Sherman Oaks.[22] Unlike previous projects that used the Cineon digital film system, Cinesite used the quicker Inferno and Flame systems for Space Jam.[22] The film's Holly render farm consisted of 16 central processing units, four gigabytes of shared memory, and took up one million dollars of the film's budget, "on top of which the deskside boxes had 256 megabytes of RAM to splurge on whatever scene you needed to create and render," explained Privett.[27]

Cinesite had begun developing proprietary software for motion tracking when working on Under Siege 2: Dark Territory (1995), which involved most of its shots incorporating a digital background; this made the company prepared for Space Jam, which consists of a bunch of moving camera shots with 3D backgrounds to be added.[22] The CGI backgrounds moved around with the motion trackers via Cinesite's proprietary software Ball Buster, which identified the markers through algorithm.[22] To avoid mistakes in the visuals as much as possible, Cinesite artists worked on the film by frame instead of viewing each shot as a whole; those, such as Jonathan Privett were dissatisfied with the method, primarily because it put them under much pressure: "We much preferred the good old fashioned run-at-24-fps, just-as-the-viewer-sees-it approach."[22]

Backgrounds

[edit]The design of the stadium was heavily dictated by that of the film's many characters, and it was such a long process that it went through 94 revisions, explained Cinesite digital effects supervisor Carlos Arguello: "Tasmanian Devil was brown so we couldn't have a wooden brown upper level, and there were so many colorful characters, and Michael Jordan and everybody had to look good in all the scenes."[27]

For scenes that take place in the stadium, shortcuts were made. For crane shots of the crowd of 15,000 people in the final basketball sequence, it was created with live-action extras, cloned animated crowd members, and a few computer-generated characters walking around the aisles in the stadium.[24] When these shots involved camera movements, a few 2D extras were animated to reflect the angle of the camera, but much lighting was added to distract from the crowd, thus minimizing this work.[27] The reflections of the floor on the gym were also "fake[d]" as raytracing would've meant rendering it for four days per a few frames.[27]

Characters

[edit]Abbate suggested the hurried workflow of the animators bled into the character animation, resulting in a quick-witted style the Looney Tunes cartoons are most known for.[10]

Although the animators had to work with almost 100 characters, they were the most focused on Bugs and Daffy not only because they were principal characters, but also because they were the most recognizable Warner Bros. characters to general audiences.[14] Sculpting was incorporated the most on Bugs and Lola, including in "beauty shots" or sequences where Bugs and Lola are together.[27] Perkins conceived the idea of the villains being secondary colors, as the main Looney Tunes were either primary colors, black, or brown.[17]

There was also a lot of experimentation with motion blur with the 2D characters, especially Tweety; as Simon Eves explained, "The workflow was that an artist would track some specific points on the sequence of 2D character-on-black that came from the animation house, and I think it was able to take a basic roto shape as well, and then it would generate an interpolated motion vector field which could be applied as a variable directional blur. The field would deform based on the relative motion of the tracking points on the camera, to produce more accurate blur as the character deformed."[22]

Release

[edit]Warner Bros. released Space Jam through its Family Entertainment division on November 15, 1996.

Home media

[edit]Warner Home Video released the film on VHS, DVD, and LaserDisc on March 11, 1997.[31] The VHS tape was reprinted and re-released through Warner Home Video's catalog promotions: The Warner Bros. 75th Anniversary Celebration (1998), Century Collection (1999), Century 2000 (2000) and Warner Spotlight (2001). The film was re-released on DVD on July 25, 2000. On October 28, 2003, the film was once again re-released as a 2-disc, special-edition DVD including newly made extras such as a commentary track, a featurette, production notes, and an hour of previously released Looney Tunes shorts and a TV special.

On November 6, 2007, Space Jam was featured as one of four films in Warner Home Video's 4-Film Favorites: Family Comedies collection DVD (the other three being Looney Tunes: Back in Action—which was released seven years after Space Jam—Osmosis Jones and Funky Monkey). On February 8, 2011, the first disc of the previous 2-disc edition was released by itself in a film-only edition DVD and on October 4, the film was released for the first time in widescreen HD on Blu-ray which, save for the Looney Tunes shorts, ported over all the extras from the 2003 2-disc edition DVD.

A double DVD release, paired with Looney Tunes: Back in Action, was released on June 7, 2016.[32] On November 15, 2016, Warner Bros. released another Space Jam Blu-ray to commemorate the film's 20th anniversary.[33]

On July 6, 2021, the film arrived on Ultra HD Blu-ray to celebrate the 25th anniversary and the release of Space Jam: A New Legacy.

Other media

[edit]Space Jam later expanded into a media franchise which includes comics, video games and merchandise. The Space Jam franchise is estimated to have generated $6 billion in total revenue. This includes a wide variety of merchandise, such as Air Jordans, Bugs Bunny shirts, Happy Meals, Mugsy Bogues jerseys, and Tweety gowns.[34]

The film was adapted into a graphic novel published by DC Comics through their imprint "Warner Bros. Family Entertainment Reading" that published the "Looney Tunes", "Tiny Toon Adventures", "Animaniacs" and "Pinky & The Brain" monthly comic books. The special issue was written by David Cody Weiss and drawn by Leonardo Batic.[35]

A licensed pinball game by Sega, a video game for the PlayStation, Sega Saturn and MS-DOS by Acclaim, and a handheld LCD game by Tiger Electronics were released based on the film.[36]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Space Jam grossed $90.5 million in the United States, and $159.7 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $250.2 million.[37]

Domestically, it debuted to $27.5 million from 2,650 theaters, topping the box office. The film then made $16.2 million in its sophomore weekend but it dropped to second place behind Star Trek: First Contact and $13.6 million in its third place behind Star Trek: First Contact and 101 Dalmatians.[4]

In China, the film was released in 1997 and grossed CN¥24.1 million.[38]

Critical response

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Space Jam holds an approval rating of 44% based on 87 reviews, with an average rating of 5.4/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "While it's no slam dunk, Space Jam's silly, Looney Toons-laden slapstick and vivid animation will leave younger viewers satisfied – though accompanying adults may be more annoyed than entertained."[39] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 59 out of 100 based on 22 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[40] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[41]

Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel of the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Tribune both gave Space Jam a thumbs up,[42] although Siskel's praise was more reserved.[43] In his review, Ebert gave the film three-and a-half stars and noted, "Space Jam is a happy marriage of good ideas—three films for the price of one, giving us a comic treatment of the career adventures of Michael Jordan, crossed with a Looney Tunes cartoon and some showbiz warfare. ... the result is delightful, a family movie in the best sense (which means the adults will enjoy it, too)."[42] Siskel focused much of his praise on Jordan's performance, saying, "He wisely accepted as a first movie a script that builds nicely on his genial personality in an assortment of TV ads. The sound bites are just a little longer."[43] Leonard Maltin also gave the film a positive review (three stars), stating that "Jordan is very engaging, the vintage characters perform admirably ... and the computer-generated special effects are a collective knockout."[44] Todd McCarthy of Variety praised the film for its humor as well as the Looney Tunes' antics and Jordan's acting.[45]

Although Janet Maslin of The New York Times criticized the film's animation, she later went on to say that the film is a "fond tribute to [the Looney Tunes characters'] past."[6] Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune complained about some aspects of the movie, stating, "...we don't get the co-stars' best stuff. Michael doesn't soar enough. The Looney Tunes don't pulverize us the way they did when Chuck Jones, Friz Freleng or Bob Clampett were in charge." Yet overall, he also liked the film, giving it 3 stars and saying: "Is it cute? Yes. Is it a crowd-pleaser? Yup. Is it classic? Nope. (Though it could have been.)" TV Guide gave the movie only two stars, calling it a "cynical attempt to cash in on the popularity of Warner Bros. cartoon characters and basketball player Michael Jordan, inspired by a Nike commercial." Margaret A. McGurk of The Cincinnati Enquirer gave the film 2+1⁄2 stars out of four writing, "Technical spectacle amounts to nothing without a good story."[46]

Veteran Looney Tunes director Chuck Jones was critical of the film and its premise, opining that Bugs Bunny would not have enlisted help from others in resolving a conflict.[47]

Accolades

[edit]- 1997 ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards

- Won: Most Performed Songs from Motion Pictures (Diane Warren for the song "For You I Will")

- Won: Top Box Office Films (James Newton Howard)

- 1997 Annie Awards

- Won: Best Individual Achievement: Technical Achievement

- Nomination: Best Animated Feature

- Nomination: Best Individual Achievement: Directing in a Feature Production (Bruce W. Smith and Tony Cervone)

- Nomination: Best Individual Achievement: Producing in a Feature Production (Ron Tippe)

- 1997 Grammy Awards

- Won: Best Song Written Specifically for Motion Picture or for Television (R. Kelly for the song "I Believe I Can Fly")

- 1997 MTV Movie Awards

- Nomination: Best Movie Song (R. Kelly for the song "I Believe I Can Fly")

- 1997 Satellite Awards

- Nomination: Best Motion Picture- Animated or Mixed Media (Daniel Goldberg, Joe Medjuck, Ivan Reitman)

- 1997 World Animation Celebration

- Won: Best Use of Animation in a Motion Picture Trailer

- 1997 Young Artist Awards

- Nomination: Best Family Feature- Animation or Special Effects

Legacy

[edit]Cultural influence

[edit]The Monstars make a cameo in the Pinky and the Brain episode "Star Warners". Jordan, who was a spokesman for MCI Communications before the film was made, would appear with the Looney Tunes characters (as his "Space Jam buddies") in several MCI commercials for several years after the film was released before MCI merged with WorldCom and subsequently Verizon Communications.[48] Bugs had previously appeared with Jordan as "Hare Jordan" in Nike ads for the Air Jordan VII and Air Jordan VIII.[49][50] In the next theatrical Looney Tunes film, Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Jordan appears in archive footage from this film as one of the disguises of Mr. Chairman (Steve Martin). In 2013, Yahoo! Screen released a parody of ESPN's 30 for 30 about the game shown in the film. The short dates the game as taking place on November 17, 1995, although Jordan's real-life return to basketball when it occurred on March 18.[51] In April 2019, the website SBNation ran a mockumentary April Fools Day episode of its popular Rewinder series on Jordan's climactic shot.[52] The Nerdlucks appeared in the Teen Titans Go! original film Teen Titans Go! See Space Jam which aired on Cartoon Network on June 20, 2021, and was released on digital on July 27, 2021.[53]

The film's official website spacejam.com, created in 1996 alongside promotion of the film, remained unchanged but active for 25 years prior to the release of the film's sequel, an unusual aspect to film promotion websites. The site was one of the earliest film promotion websites, and included a number of unrefined web design facets, such as heavy use of animated GIFs. While the site's content had been moved under Warner Bros.'s site around 2003, the site's design gained a resurgence of interest around 2010 as an historical artifact of the early days of the web, and Warner Bros. returned the site to the spacejam.com address in response.[54] Following the release of Space Jam: A New Legacy's first trailer in April 2021, the website was updated for promotion of the new film, though the 1996 content remained available as a separate landing page.[55]

A television film crossover with Teen Titans Go!, Teen Titans Go! See Space Jam, aired on Cartoon Network in June 2021. The film features the Teen Titans meeting the Nerdlucks and providing humorous commentary over the original film. The movie's length is slightly abridged, omitting the opening credits and several scenes that do not feature the Looney Tunes, and the soundtrack is replaced by an original score.[56]

Sequel

[edit]A sequel to Space Jam was planned as early as 1996. As development began, Space Jam 2 was going to involve a new basketball competition with Michael Jordan and the Looney Tunes against a new alien villain named Berserk-O!. Artist Bob Camp was tasked with designing Berserk-O! and his henchmen. Joe Pytka would have returned to direct while Cervone and his creative partner Spike Brandt signed on to direct the animation sequences. However, Jordan did not agree to star in a sequel, and Warner Bros. eventually cancelled plans for Space Jam 2.[57]

Several potential sequels, including Spy Jam with Jackie Chan that would end up becoming the basis for Looney Tunes: Back in Action, Race Jam with Jeff Gordon, Golf Jam with Tiger Woods,[58][59] and Skate Jam with Tony Hawk were all discussed but never came to be.[60]

In February 2014, Warner Bros. officially announced development of a sequel that will star LeBron James.[61] In July 2015, James and his film studio, SpringHill Entertainment, signed a deal with Warner Bros. for television, film and digital content after receiving positive reviews for his role in Trainwreck.[62][63][64] By 2016, Justin Lin signed onto the project as director, and co-screenwriter with Andrew Dodge and Alfredo Botello.[65] By August 2018, Lin left the project, and Terence Nance was hired to direct the film.[66] In September 2018, Ryan Coogler was announced as a producer for the film.[67] Filming would take place in California[68][69] and within a 30-mile radius of Los Angeles.[70] Prior to production, the film received $21.8 million in tax credits as a result of a new tax incentive program from the state.[68][71][72]

In February 2019, after releasing the official logo with a promotional poster, Space Jam 2 was announced to be scheduled for release on July 16, 2021.[73] Principal photography began on June 25, 2019.[74][75] On March 4, 2021, it was confirmed that the sequel would also feature various characters in the Warner Bros. film and television archive.[76]

Jordan was reportedly set to make a cameo in Space Jam 2, as the makers teased the fans in June 2021 that "Jordan will appear in the film, but not in the way you would expect it." In fact, as shown in the film, he appeared in various pictures from his career and the Space Jam film. In a scene, Sylvester claimed to have found Jordan, but he actually found actor Michael B. Jordan, who thus made the cameo expected to be made by the former Bulls star.

After the release of Space Jam 2, a third film was in talks by director Malcolm D. Lee with Dwayne Johnson involved as the lead, transitioning on the sports genre from basketball to professional wrestling.[77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "Space Jam". Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (November 26, 1996). "What's Up, Doc? Warner Bros. Animation Thanks to 'Space Jam'". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

Max Howard, president of Warner Bros. Feature Animation, admitted he didn't expect the impressive showing of Space Jam:

- ^ a b c d e f g h Twenty years later, ‘Space Jam’ is the movie we never knew we needed. Archived February 18, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The Washington Post. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ a b "Space Jam (1997)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Space Jam (1996), November 15, 1996, retrieved July 11, 2021

- ^ a b c d e f g h Maslin, Janet (November 15, 1996). "Icons Meet: Bugs, Daffy And Jordan". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 31, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ @bobbergen (March 23, 2021). "Barnyard Dog in Space Jam. HH in several projects" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c Bittner 1996, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lawrence, Derek (November 15, 2016). "Space Jam: The story behind Michael Jordan's improbable victory". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lyons 1996a, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Failes, Ian (November 15, 2016). "The Oral History of 'Space Jam': Part 1 – Launching the Movie". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "His Airness vs. Air: The making of 'Space Jam' Jordan conquers another challenge: The movies - Chicago Tribune". Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Lior (July 14, 2021). "Hoop There It Is". The Ringer. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bittner 1996, p. 55.

- ^ Greene, James (December 3, 2012). "Sufferin' Succotash! Looney Tunes Voice Actor Joe Alaskey On Bugs Bunny, Geraldo, & Why He Wasn't In 'Space Jam'". Vulture.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Dur, Taimur (July 14, 2021). "INTERVIEW: Billy West reveals how The Howard Stern Show led to voicing Bugs Bunny in Space Jam". The Beat (Interview). Archived from the original on July 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lyons 1996b, p. 13.

- ^ Bittner 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Bittner 1996, p. 55–56.

- ^ a b Bittner 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Lyons 1996b, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Failes, Ian (November 16, 2016). "The Oral History of 'Space Jam': Part 2 – The Perils of New Tech". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Lyons 1996b, p. 10.

- ^ a b Lyons, Mike (December 1996). "Space Jam: Special F/X". Cinefantastique. Vol. 28, no. 6. p. 12.

- ^ Lyons 1996a, p. 9.

- ^ Lyons 1996, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f Failes, Ian (November 18, 2016). "The Oral History of 'Space Jam': Part 3 – Reflections on A Beloved Film". Cartoon Brew. Archived from the original on July 2, 2020. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- ^ "RIAA Gold and Platinum Searchable Database". Archived from the original on February 23, 2011. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ "Grammy- Past Winners Search". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ Ma, David (July 16, 2021). "Biz Markie, Pioneering Beatboxer and 'Just a Friend' Rapper, Dies at 57". NPR.

- ^ "New Video Releases". The New York Times. March 7, 1997. p. B15. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "Space Jam/Looney Tunes: Back in Action". Amazon.com. December 17, 2016. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ^ ""Space Jam" 20th Anniversary" (Press release). Warner Bros. October 20, 2016. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "Let's Be Honest, 'Space Jam' Actually Sucked". Highsnobiety. September 29, 2018. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ "Leonardo Batic". lambiek.net. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ "Celebrity Sightings". GamePro. No. 92. IDG. May 1996. p. 21.

- ^ "Space Jam". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Plasser, Gunda (2002). Southern California and the World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-275-97112-0. Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ "Space Jam". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ "Space Jam". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Cinemascore". Archived from the original on December 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (November 15, 1996). "Space Jam Movie Review & Film Summary (1996)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 1, 2014 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (November 15, 1996). "Mj Delivers on the Screen In 'Space Jam'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 4, 2009). Leonard Maltin's 2010 Movie Guide. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-101-10876-5. Retrieved October 1, 2014 – via Google Books.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (November 17, 1996). "Film Reviews: Space Jam". Variety. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ McGurk, Margaret (November 15, 1996). "Dazzle of 'Space Jam' can't hide its lame story". The Cincinnati Enquirer. p. 26. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Boone, Brian (May 20, 2020). "The Untold Truth Of Space Jam". Looper.com. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Porter, David L. (2007). Michael Jordan: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33767-3. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- ^ Hare Jordan & Air Jordan - Air Jordan VII Archived July 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine YouTube (created by Nike and Warner Bros.)

- ^ Hare Jordan & Air Jordan - Air Jordan VIII Archived January 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine YouTube (created by Nike and Warner Bros.)

- ^ ESPN 30 for 30 Short - Tune Squad vs. Monstars (the Space Jam Game) Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine YouTube (created by Yahoo! Screen and Warner Bros.)

- ^ "Michael Jordan's life-saving dunk from Space Jam gets a deep rewind". Secret Base. April 4, 2010. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Robin & Co. Cheer on the Tunes in 'Teen Titans Go! See Space Jam' Original Movie". May 27, 2021. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ Malinowski, Erik (August 19, 2015). "'Space Jam' Forever: The Website That Wouldn't Die". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 3, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Hollister, Sean (April 3, 2021). "25 years later, Space Jam has a new website – and the first trailer for the sequel". The Verge. Archived from the original on April 3, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Liu, Narayan (May 27, 2021). "Cartoon Network Goes Meta with Teen Titans Go! See Space Jam Movie". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 27, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ "Artist Bob Camp recalls the ill-fated "Space Jam 2"". Animated Views. November 30, 2012. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2014.

- ^ ""Space Jam" Director Reveals Spike Lee Almost Wrote the Film, Scrapped Tiger Woods Sequel". Mr. Wavvy. November 15, 2016. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Space Jam 2 You Never Saw Almost Featured Tiger Woods". November 15, 2016. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ Hawk, Tony (January 5, 2019). "Production still". Twitter. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ Busch, Anita (February 21, 2014). "Ebersols Aboard To Produce And Script Warner Bros' 'Space Jam 2′ As A Starring Vehicle For LeBron James". Deadline. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "LeBron James signs with Warner Bros., stokes rumors of 'Space Jam' sequel". Los Angeles Times. July 22, 2015. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.

- ^ "LeBron James: I'll help pay for hundreds of kids to go to college". TODAY.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (August 14, 2015). "LeBron James Hopeful for 'Great Things' in 'Space Jam 2′". Collider. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (May 2, 2016). "Justin Lin Circling 'Space Jam' Sequel Starring LeBron James (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ^ Gonzalez, Umberto (August 3, 2018). "'Space Jam 2': Terence Nance in Advanced Talks to Direct Lebron James (Exclusive)". The Wrap. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2018.

- ^ "SpringHill Ent. on Twitter". Twitter. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ a b McNary, Dave (November 19, 2018). "LeBron James' 'Space Jam 2' Set to Film in California". Variety. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Space Jam 2 Will Shoot in California". MovieWeb. November 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ ""Space Jam 2" To Film in California - Dark Horizons". Dark Horizons. November 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "'Space Jam 2' Among Projects to Receive California Tax Credits". TheWrap. November 19, 2018. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ Ng, David (November 19, 2018). "'Space Jam 2,' starring LeBron James, to receive $21.8-million tax break to shoot in California". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2018.

- ^ "Announcement". Twitter. February 22, 2019. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- ^ "Production Begins on LeBron James' Space Jam 2". ComingSoon.net. June 26, 2019. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ "Space Jam 2: Lebron James Confirms Start of Production". ScreenRant. June 25, 2019. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

- ^ Haylock, Zoe (March 4, 2021). "The Space Jam Sequel Will Send LeBron James Through the Warner Bros. Film Archive". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Sanchez, Gabrielle (July 21, 2021). "Space Jam: A New Legacy director Malcom D. Lee is down to make a third film starring Dwayne Johnson". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 24, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bittner, Drew (December 1996). "Space Jam". Starlog. No. 233. pp. 52–57.

- Lyons, Mike (November 1996a). "Space Jam". Cinefantastique. Vol. 28, no. 4/5. pp. 7–9.

- Lyons, Mike (December 1996b). "Space Jam". Cinefantastique. Vol. 28, no. 6. pp. 10–11, 13.

External links

[edit]- 1996 films

- Space Jam

- 1996 animated films

- 1996 children's films

- 1996 comedy films

- 1990s American animated films

- 1990s children's animated films

- 1990s fantasy comedy films

- 1990s science fiction comedy films

- 1990s sports comedy films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about alien visitations

- American alternate history films

- American basketball films

- American fantasy comedy films

- American science fiction comedy films

- American slapstick comedy films

- American sports comedy films

- American films with live action and animation

- Animated films about extraterrestrial life

- Animated films based on animated series

- Animated films about parallel universes

- Animated crossover films

- Animated sports films

- Bugs Bunny films

- Rotoscoped films

- Works based on advertisements

- Films about animation

- Films adapted into comics

- Films directed by Joe Pytka

- Films produced by Ivan Reitman

- Films with screenplays by Herschel Weingrod

- Films with screenplays by Timothy Harris (writer)

- Films scored by James Newton Howard

- Michael Jordan

- Cultural depictions of Vlade Divac

- Looney Tunes films

- Films set in Chicago

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in amusement parks

- Films set on fictional planets

- Films set in 1973

- Films set in 1993

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Chicago

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films shot in New York City

- Warner Bros. animated films

- Warner Bros. Animation animated films

- Films about the NBA

- 1996 science fiction films

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- English-language science fiction comedy films

- Warner Bros. films

- English-language fantasy comedy films

- English-language sports comedy films