I Taw a Putty Tat

| I Taw a Putty Tat | |

|---|---|

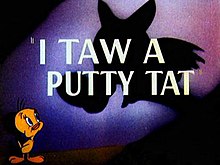

The original title card of the cartoon | |

| Directed by | I. Freleng |

| Story by | Tedd Pierce[1] |

| Starring | Mel Blanc |

| Music by | Carl Stalling |

| Animation by | Virgil Ross Gerry Chiniquy Manuel Perez Ken Champin Pete Burness (uncredited) |

| Layouts by | Hawley Pratt |

| Backgrounds by | Paul Julian |

| Color process | In: Cinecolor (two-strip, original release) Print by: Technicolor (production, three-strip, reissue) |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 7 minutes (one reel) |

| Language | English |

I Taw a Putty Tat is a 1948 Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies animated cartoon directed by Friz Freleng.[3] The short was released on April 1, 1948, and stars Tweety and Sylvester.[4]

Both Tweety and Sylvester are voiced by Mel Blanc. The uncredited voice of the lady of the house (seen only from the neck down, as she talks on the phone) is Bea Benaderet.[5]

This is the first film whose title included Tweety's speech-impaired term for a cat.

Plot

[edit]Sylvester awaits the arrival of a new canary after the previous house bird has mysteriously disappeared (one of several such disappearances, according to stencils the cat keeps on a wall hidden by a curtain, confirmed by his "hiccup" of some yellow feathers). Upon the arrival of the bird, Sylvester pretends to play nice in order to abuse and eventually make a meal of the sadistic canary.

A series of violent visual gags ensues in which Tweety physically subdues the threatening cat by smoking him up, hitting him on the foot with a mallet, feeding him some alum and using his uvula as a punching bag.

A couple of racial or ethnic gags are included. Sylvester imitates a Swedish-sounding maid, in an imitation of radio comedian El Brendel, who feigns complaining about having to "clean out de bird cage." He reaches into the covered cage and grabs what he thinks is the bird. The canary whistles at him. The confused cat opens his fist to find a small bomb, which promptly explodes, covering the cat in "blackface" makeup. His voice pattern then changes to something sounding like "Rochester", when he utters, "Uh-oh, back to the kitchen, ah smell somethin' burnin'!" just before passing out in the doorway. (This gag is often edited out for television broadcasts.)

A more subtle gag occurs when Tweety, inside the cat's mouth, yells down its gullet. The answer comes back, "There's nobody here but us mice!", which is a reference to the Louis Jordan hit "Ain't Nobody Here but Us Chickens" (1946).

At the climax, Tweety has managed to trap Sylvester inside the birdcage, and has introduced a "wittle puddy dog" (rhymes with "puppy dog"; a not-so-little "pug dog", an angry bulldog - in his first appearance). Their deadly battle occurs under the wrap the bird has thrown over the cage.

The film ends with the lady of the house calling the pet shop again, this time ordering a new cat, while Tweety lounges in Sylvester's old bed. Overhearing the woman telling the pet shop that the cat will have a nice home here, Tweety reveals the silhouette of a cat now stencilled on the wall, and closes the cartoon with a comment to the camera, "Her don't know me very well, do her?" a variant on one of Red Skelton's catchphrases by his "Mean Widdle Kid" character from radio.

History

[edit]This cartoon is a color remake of a black and white short film titled Puss n' Booty (1943) which was directed by Frank Tashlin and written by Warren Foster (who would later be the main writer for most Tweety/Sylvester cartoons in the 1950s, such as Tweety's S.O.S., Snow Business and the Oscar-winning Birds Anonymous). In this previous version, a generic cat and canary team called Rudolph and Petey were used but the plot along with some gags and story elements were re-used. Puss N' Booty was notable as it was the final black and white cartoon ever released by WB.

After winning the Academy Award for Animated Short Film in 1947 for Tweetie Pie, a film which combined for the first time two of the studio's latest animated stars, Tweety Bird and Sylvester, there was a demand for more short films using the characters. Freleng himself said he could not imagine Tweety working with any other partners than Sylvester (in contrast, Sylvester still had his fair share of cartoons without Tweety and later Speedy Gonzales).

I Taw a Putty Tat was Freleng's second film teaming the characters and was released less than a year after Tweetie Pie. It is noticeable that while this cartoon was directed by Friz Freleng, the Tweety we see in it is by far closer to the aggressive little bird used in his first few cartoons directed by Bob Clampett than the more subdued and naive character he would become a few years later as the series progressed.

The short is also the first time in a Sylvester/Tweety short where Sylvester speaks.

Production

[edit]Bea Benaderet provided the voice of the housemistress but she did not get credit as with most voice actors at the studio, Mel Blanc being the exception. Amongst the musical quotations in the Carl Stalling film score (with or without lyrics accompanying them) are extracts from Singin' in the Bathtub, She Was an Acrobat's Daughter and Ain't We Got Fun.

The animators for the cartoon were Ken Champin, Gerry Chiniquy, Manuel Perez, Virgil Ross, and an uncredited Pete Burness. Paul Julian was the background artist, while Hawley Pratt was the layout artist.

Home media

[edit]- Bugs Bunny: Superstar, Part 1 (1975) (uncut) on Looney Tunes Golden Collection: Volume 4

- The Golden Age of Looney Tunes, Volume 4 Laserdisc set.

- Romance on the High Seas, edited

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Beck, Jerry (1991). I Tawt I Taw a Puddy Tat: Fifty Years of Sylvester and Tweety. New York: Henry Holt and Co. p. 94. ISBN 0-8050-1644-9.

- ^ Cue: The Weekly Magazine of New York Life. (1948). United States: Cue Publishing Company.

- ^ Beck, Jerry; Friedwald, Will (1989). Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies: A Complete Illustrated Guide to the Warner Bros. Cartoons. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. p. 143. ISBN 0-8050-0894-2.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Scott, Keith (2022). Cartoon Voices from the Golden Age, 1930-70. BearManor Media. p. 73. ISBN 979-8-88771-010-5.

External links

[edit]- 1948 films

- 1948 animated films

- 1948 short films

- Merrie Melodies short films

- Sylvester the Cat films

- Tweety films

- Animated films about dogs

- Short films directed by Friz Freleng

- Films scored by Carl Stalling

- Warner Bros. Cartoons animated short films

- 1940s Warner Bros. animated short films

- Hector the Bulldog films