Modibbo Raji

Modibbo Raji | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | Muhammad Raji b Ali 1790 Maratta, Gobir, present-day Republic of Niger. |

| Died | 1865 (aged 74–75) |

| Resting place | Yola |

| Religion | Islam |

| Children | Abubakar (Alfa), Usman (Baba Modibbo), Mustafa (Ba Dikko), Ahmad (Ba Sambo), Murtala (Baba Girei), Isa (Gaji), Amina, Zainab (Goggo Abu), Asma'u (Goggo Nana), Fatima (Goggo Zahra'u), Hajara (Goggo Hamdalla), Maimuna (Goggo Muna), Hafsat (Goggo Peto) |

| Parents |

|

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Sect | Tijaniyya |

| Jurisprudence | Maliki |

| Teachers | Usman dan Fodio Abdullahi dan Fodio |

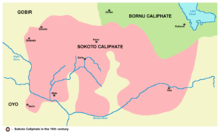

Modibbo Raji (Arabic: محمد راجي بن علي بن أبو بكر; 1790 – 1865) was a 19th-century Fulani Islamic scholar who was part of the community of Usman Dan Fodio, founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, and his brother Abdullahi dan Fodio.[1] After a long career as a teacher, Qadi, Naib (deputy Imam) and Wazir (vizier) in the Gwandu Emirate under his mentor Abdullahi dan Fodio and his successors, Modibbo Raji emigrated in the 1850s and eventually settled in Adamawa.[2] He is generally regarded as the founder of the Islamic scholarly tradition in Adamawa as well as one of the earliest exponents of the Tijjaniyya Islamic sect in the Sokoto Caliphate. He died c. 1865 and was buried in Yola leaving behind his writings both in Arabic and Fulfulde, and a large scholarly community of his sons, daughters, students and associates.[1]

Early life and time in Gwandu

[edit]Modibbo Raji was born in Maratta (in present-day Republic of Niger) to Aliyu Ibn Abubakar who had moved from Zinder to join the community of Usman dan Fodio, which was at the time based in Maratta.[1] His mother Rabi’ah was dan Fodio's cousin.[2] He was taught the Quran as a little boy by his mother after which he obtained advanced Islamic education under both Usman and Abdullahi dan Fodio. The latter remained his teacher and mentor until death. The community subsequently moved to Degel (in present-day Sokoto State, Nigeria) where Modibbo Raji continued his early education. He was 14 years old at the start of Usman Dan Fodio's Jihad. With the establishment of Gwandu Emirate, he went to live there under his teacher Abdullahi dan Fodio, who gave him his daughter in marriage.[2] He rose to become a teacher in Abdullahi Fodio's school and a Qadi under Abdullahi's successor Emir Muhammad (1829–35). He was the deputy or Naib of Emir Muhammad's successor Emir Ibrahim Khalil (1835–60).[2] A few years after the death of Abdullahi dan Fodio in 1828, Modibbo Raji was initiated into the Tijjaniyya Islamic sect by al-Hajj Umar al-Futi. However, he initially kept his membership of the sect secret because the Sokoto establishment at the time belonged to the Qadiriyya sect. He didn't reveal his allegiance to the Tijjaniyya until he had retired from his public roles c. 1848.[1]

Migration to Adamawa

[edit]

Modibbo Raji decided to emigrate during the reign of Emir Khalil of Gwandu, a decision that may have partly emanated from his initiation into the Tijjaniyya sect.[1] Another possible reason was his increasing disillusionment with what was in his view, the setting of decadence in the Caliphate which he clearly alluded to in his Fulfulde poem Alaamaaji Ngirbuki (Signs of Collapse).[3] After openly acknowledging his membership of Tijjaniyya, Modibbo Raji sought permission from Emir Khalil to emigrate. His intention was to travel to the Holy Land, perform the Hajj and eventually settle on the banks of the Nile. The Emir Khalil was initially opposed to the plan but later came around to grant permission.[4] In c. 1855, accompanied by most of his family members, his students and their families, Modibbo Raji left Gwandu and travelled eastwards through Katsina and Kano where he met new companions (who were Islamic scholars in their own right) like Modibbo Nakashiri, Modibbo Sufyanu and Malam Muhammad Na Gano, who either travelled with him or joined him later in Yola. On arrival in Yola, Modibbo Raji was warmly welcomed by the emir Lamido Lauwal who sought to discourage him from proceeding to the East. The Lamido granted a piece of land just south of Yola for Modibbo Raji and his companions to settle, a location that has now grown into the settlement of Wuro Modibbo.[5] Two years later, in c. 1857, Modibbo Raji left Yola to continue his eastward journey. In the 1980s, his descendants built a school in his memory at Wuro Modibbo.

Stay in Kalfou

[edit]

At the eastern boundary of Adamawa Emirate, Modibbo Raji was unable to continue his journey because of troubles in the Sultanate of Bagirmi in the present-day Republic of Chad. He therefore remained in the sub-emirate of Kalfou (in the present-day Far North Region of Cameroon) and founded the settlement of Dinawo (religious town) while waiting for the return of peace to Bagirmi to continue his journey.[1] In the 19th century, Muslim scholars commanded large personal following distinct from those of the rulers in whose territory they settled. The community that he had founded in the Kalfou sub-emirate was distinct by virtue of its Tijjaniyya inclination. This was a source of worry for the then ruler of Kalfou Lamdo Koiranga who appealed to Lamido Lauwal at Yola for a solution. The Lamido then prevailed on Modibbo Raji to return to Yola after a sojourn of several years in Dinawo.[1]

Return to Yola and death

[edit]Modibbo Raji returned to Yola and was housed near the residence of the head of the Lamido's palace guards (Sarkin Dogarai). It was there that he died seven months later at the age of 75 in c. 1865. He was buried within the residence, the site of which has remained a family burial ground (Hubbare) up to the present day.[5]

Legacy

[edit]Modibbo Raji was one of the foremost Islamic scholars in Gwandu Emirate in its early years, and later in Adamawa Emirate. He was also one of the pioneer leaders of Tijjaniyya in the old Sokoto Caliphate, being one of its earliest initiates in the area.[6] In addition to his teaching, judicial and administrative careers, he was also renowned for his writings (in Arabic and Fulfulde) in a literary career that lasted for almost 60 years from 1806 up to his death in 1865.[2] Upon his death, his sons and companions moved out of Yola to settle in and around the nearby town of Girei where they established the most prominent Islamic scholastic community of their time.[1] His sons include Modibbo Usmanu (Baba Modibbo), Modibbo Abubakar (Alfa), Modibbo Murtala (Baba Girei), Modibbo Ahmadu (Ba Sambo), Modibbo Musdafa (Ba Dikko) and Modibbo Isa (Gaji).[5] Modibbo Usmanu was the most prominent member of the late 19th century group of Islamic scholars known by historians as the Girei Ulama.[7] Apart from being a noted scholar and teacher, he held the posts of Chief Qadi of Girei and Chief Imam of Girei central mosque. As Chief Qadi, he was in charge of the northern sub-emirates of Adamawa from Maroua down to Ngaoundere. He died in 1906, a few years after the establishment of colonial rule in Nigeria. Among his students were Modibbo Girei Ahmadu,[1]: 301 a onetime judicial member of the Lamido's Council and Alkali Hamma Joda,[8] a onetime Chief Qadi of Yola. Modibbo Raji's companions Modibbo Nakashiri[9] and Modibbo Sufyanu were also high-ranking members of the Girei scholastic community. One of Modibbo Raji's students Muhammad Tanu Mo’ililal was a prominent Islamic scholar and writer in the later part of the 19th century in Yola.[1]: 212 Modibbo Nakashiri's daughter Amina a.k.a. Inna Jangirde (1877-1947) who is a descendant of Modibbo Raji on her mother's side, was a noted Islamic teacher in Yola who once taught prominent members of the ruling house of Adamawa.[9] Some of Modibbo Raji's daughters were also noted Quranic teachers who ran schools for children and conducted Tafsir for women. The most learned among them were Zainabu (Goggo Abu), Asma'u (Goggo Nana) and Hafsatu (Goggo Peto).[1]: 212

Modibbo Raji's grandchildren like Modibbo Dahiru (later known as Galadima Dahiru) and Modibbo Mu'azu were also noted for Islamic scholarship in the early to middle years of the 20th century.[10] Modibbo Dahiru's students at Yola include Wakili Chamba Hamman Tukur and Liman Husseini who was one of the longest-serving Chief Imams of Yola. Modibbo Dahiru along with his cousin Muhammadu Girei (later known as Sardauna) and Mallu Hamman (later known as Waziri Mallu Hamman) were the first natives of Adamawa to undergo Western education when they were sent by the provincial administration in 1911 to attend the new school run by Hanns Vischer (Dan Hausa) in Kano.[10] Upon his return from Kano, Modibbo Dahiru became the first Native Treasurer in the then Yola Province. Later in 1919, he was appointed by Lamido Muhammad Abba as the third Galadima of Adamawa,[10] a title that has now been held by successive descendants of Modibbo Raji for over 100 years.[1]: 432 Other grandchildren of Modibbo Raji were appointed as district heads of Chubunawa, Maiha (Sardauna Muhammadu Girei),[1]: 407 Ga’anda, Mambilla (Usman Muqaddas)[11] and Madagali (Dan Galadima Dahiru Aminu, a great-grandson) at various times in the early to mid-20th century. Galadima Aminu, also a grandson of Modibbo Raji, was one of the longest serving senior councillors in Adamawa Emirate.[12] He held the post of Galadima Adamawa from 1921 to 1967 during which he also doubled as the District Head of Yola (and Jimeta) between 1934 and 1958.[1]: 410 [13]

Later descendants of Modibbo Raji have played prominent roles in the civil service, politics, military, business, academia and various professions in post-independence Nigeria. In their home state of Adamawa, his hundreds of descendants are found mainly in Yola South, Yola North, Girei, Mayo Belwa, Gombi and Song local government areas. Over a century of intermarriage among the descendants of Modibbo Raji and those of his companions Modibbo Nakashiri, Modibbo Sufyanu and Malam Muhammad Na Gano[1]: 366 has created a large, unified community of descendants referred to as the 'Fulbe Hausa', which means the Fulani who came from Hausaland.[14]

Fulfulde

[edit]- Laamii'do mo hawtaaka nusal

- Alaamaaji ngirbuki

- Finndin daanii'do

- Ter'de juul'de

- Yah gi'do am

- Yimre furuu'a

- Yimre yeyraa'be

- Shenii'do Raji

Arabic

[edit]- Ajwiba

- Irshad al-habib ila maqasid al-labib

- Kitab al-jawab

- Lubab al-din

- Al-Qal sa’adat al-mar li-husn al-fal

- Qasidah mimiyya fi ‘l-tasawwuf

- Tahdhir al-Su'adah al-Fa'izin min Ittaiba al-Ashqiya al-Khasirin

- Risala ila amir Gwandu Khalil

- Wasiyya

In the name of God the Merciful and the Compassionate, may the blessing of

God be upon the noble Prophet and his followers in the path of the upright

religion.

From the slave of God Muhammadu Raji b. Ali to the emir of affairs, the wali

of advice, the Wazir, the son of our noble sister Asma' the daughter of the Sheikh,

most perfect peace and most perfect greetings and respect.

This is to let you know our news and that we, praise be to God, are well and in

good health. We have reached the land of the Imam Adama peacefully in regard

to both our religious and worldly affairs, all through your blessing (baraka).

And indeed your messenger, the emir Kassan had exerted himself to fulfill your

wishes and obey your commands, so much so that he executed all your instructions.

We are grateful to you and him. May God place you on the Day of Resurrection

among the leading or chosen people.

Next, convey our greetings to the amir-al-mu'minin (Ali b. Bello 1842-59) and

convey to him our prayer and gratitude - may God increase his greatness and

sovereignty. Indeed he has brought all of us under his authority through his bounty;

verily, his Blessings never allowed us to be thirsty or hungry - praise be to God.

Next, I have learnt from numerous reports that the route to the Holy Places is

impossible except through association with and befriending the unbelievers and

obeying their orders all the way from here to the Holy Places. I did not accept

bargaining with my religion in this manner though a number of the Ulama have

done so. In fact, our Sheikh b. Fodiyo said "To have association with a Kafir

- unbeliever, who is immoral and oppressive, is a sin even if done only outwardly."

Because of this, I turned to the right-handside and stayed in the land of

Lawal b. Adama.

Elegy

[edit]Modibbo Raji's elegy Woyrude Modibbo Raji,[16] also referred to as Fayaa Fukarabe, was composed by his student Muhammad Tanu Mo'Ililal. The 31-verses-long elegy was composed in the Fulfulde language and written in the Ajami script. In this audio file, the elegy is recited by Hadijatu Adda Yola a widow of Modibbo Raji's grandson Galadima Bello Ahmad.

Further reading

[edit]- Abba, I. Alkali. "Islam in Adamawa in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries." M.A. Thesis, ABU, 1976

- Abubakar, Sa'ad. "The Foundation of an Islamic Scholastic Community in Yola." Paper presented at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Seminar, ABU, 1972

- Muhammad Tanu Mo'ililal. Fayaa Fukarabe (an elegy on Modibbo Raji's death), NHRS, ABU Zaria

- Kirk-Greene A.H.M., Adamawa Past and Present, (London, 1958)

- Strumpell, Kurt. History of Adamawa according to oral tradition. In: Special print from messages from the Geographical Society in Hamburg. Volume 26, Hamburg 1912

External links

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Abubakar, Sa'ad (2008). Lamibe Fombina: A History of Adamawa Emirate, 1809-2008. Ibadan: Book Wright Nigeria (Publishers). pp. 213–217. ISBN 978-978-245-744-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Hunwick, John (1994). Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of central Sudanic Africa Vol.2. Volume 13. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 434–436. ISBN 9004104941.

- ^ Bobboyi, Hamid (2008). Ajami literature and the study of the Sokoto Caliphate. In: S. Jeppie, SB Diagne (Eds). The Meanings of Timbuktu. Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0796922045.

- ^ Last, DM (1967). Literature of the North: Additions to the collection of Manuscripts on Microfilm at Zaria 1966-67. Zaria: Northern History Research Scheme, Second Interim Report. pp. 31 ff.

- ^ a b c Raji, AM. (1978). The life and career of Modibbo Muhammad Raji B. Ali 1790-1862. B.A. Thesis. Bayero University, Kano.

- ^ Njeuma, MZ (2012). Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG. p. 97. ISBN 978-9956726950.

- ^ M. Abba, A. Fari, Y. Wali. The role of Girei Ulama in sustaining the government and administration of the emirate of Fombina 1809-1901. In S. Abubakar (Ed). Papers on Nigerian History, Vol.1, Abuja 1996, p. 69.

- ^ Njeuma, MZ (2012). Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG. p. 112. ISBN 9956726958.

- ^ a b Hunwick, John (1994). Arabic Literature of Africa: The writings of central Sudanic Africa Vol.2. Volume 13. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. pp. 437. ISBN 9004104941.

- ^ a b c Tukur, MM (2016). British Colonisation of Northern Nigeria, 1897-1914. A Reinterpretation of Colonial Sources. Dakar, Senegal: Amalion Publishing. p. 486. ISBN 9782359260465.

- ^ Hare, John (2013). Last Man In. The End of Empire in Northern Nigeria. Kent, UK: Neville & Harding. p. 102. ISBN 9780948028038.

- ^ Njeuma, MZ (2012). Fulani Hegemony in Yola (Old Adamawa) 1809-1902. Bamenda, Cameroon: Langaa RPCIG. p. 240. ISBN 9956726958.

- ^ "Yola district gets new ruler". Blueprint. August 19, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Tukur, MM (2016). British Colonisation of Northern Nigeria, 1897-1914. A Reinterpretation of Colonial Sources. Dakar, Senegal: Amalion Publishing. p. 512. ISBN 9782359260465.

- ^ Hamid Bobboyi, Alkasum Abba (2009). Adamawa Emirate 1809-1901, A Documentary Source Book. Abuja: Centre for Regional Integration. pp. 150–152. ISBN 9789789011292.

- ^ Waynude Modibbo Raji [19th century ], British Library, EAP387/1/4/1, https://eap.bl.uk/archive-file/EAP387-1-4-1