Migration of the Serbs (painting)

Seoba Srba[a] (English: Migration of the Serbs) is a set of four similar oil paintings by the Serbian artist Paja Jovanović that depict Serbs, led by Archbishop Arsenije III, fleeing Old Serbia during the Great Serb Migration of 1690–91. The first was commissioned in 1895 by Georgije Branković, the Patriarch of Karlovci, to be displayed at the following year's Budapest Millennium Exhibition. In the view of the Serbian clergy, it would serve to legitimize Serb claims to religious autonomy and partial self-administration in Austria-Hungary by upholding the contention that Serbs left their homeland at the behest of the Holy Roman Emperor to protect the Habsburg monarchy's borders.

Measuring 380 by 580 centimetres (150 by 230 in), the first painting was completed in 1896, and presented to Patriarch Georgije later that year. Dissatisfied, the Patriarch asked Jovanović to adjust his work to conform with the Church's view of the migration. Though Jovanović made the changes relatively quickly, he could not render them in time for the painting to be displayed in Budapest, and it therefore had to be unveiled at the Archbishop's palace in Sremski Karlovci. Jovanović went on to complete a total of four versions of the painting, three of which survive. The first version is on display at the patriarchate building of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Belgrade, the second at the Pančevo Museum, and the fourth at Princess Ljubica's Residence, in Belgrade. Migration of the Serbs holds iconic status in Serbian popular culture, and several authors repute it to be one of Jovanović's finest achievements.

Background

[edit]Great Serb Migration (1690–91)

[edit]

In 1689, Arsenije III, the Archbishop of Peć, incited Serbs in Kosovo, Macedonia and the Sandžak to revolt against the Ottoman Empire and support a Habsburg incursion into the Balkans.[2] On 2 January 1690, the Habsburgs and Serbs were defeated in battle at the Kačanik Gorge. The Habsburgs began to retreat, prompting thousands of Serb villagers to leave their homes and flee north fearing Ottoman reprisals.[3] In Serbian historiography, this event came to be known as the Great Serb Migration.[4] Between 30,000 and 40,000 Serb refugees streamed into Habsburg-held Vojvodina, north of the Danube River, and settled there.[5] The migrants would come to call the regions they had formerly inhabited Old Serbia, and dubbed their adopted homeland "new Serbia".[6]

In 1691, Arsenije struck a deal with Leopold I, who was Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary, whereby the Habsburgs granted the Serbs ecclesiastic autonomy and some degree of self-administration, much to the displeasure of the Roman Catholic Church and Hungarian authorities.[7] Leopold recognized Arsenije as the leader of Habsburg Serbs in both religious and secular affairs, and indicated that this power would be held by all future Archbishops. In 1712, Sremski Karlovci became the Patriarchate for Serbs living in the Habsburg Empire.[8]

Commissioning

[edit]

In the early 1890s, Hungarian officials announced plans for a Budapest Millennium Exhibition to be held in 1896; it was intended to mark the 1,000th anniversary of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, reaffirm Hungary's "national and territorial legitimacy" and the Hungarian people's "natural and historical right in the areas they inhabited."[9] The Exhibition was to be held at Budapest's City Park. Exhibits were to be divided into twelve distinct areas, one of which was visual art.[10] The showpiece of the art exhibit was The Conquest of the Carpathian Basin, a painting by Hungary's foremost history painter, Mihály Munkácsy, that was located in the Hungarian Parliament Building.[11] Several pavilions displaying the cultural and industrial achievements of non-Hungarians living in the Hungarian-administered territories of Austria-Hungary were also built, including one for the Serbs.[12]

In the spring of 1895, on the orders of the Patriarch of Karlovci, Georgije I, the Congress Board of Sremski Karlovci commissioned the young realist Paja Jovanović to paint Migration of the Serbs, intending for it to be displayed as part of the Serb pavilion. Georgije had originally approached the artist Uroš Predić, but Predić said it would take him two years to complete the painting. Jovanović assured the Patriarch that he could finish the work in eight months.[11] The painting was one of two works that Jovanović was hired to paint for the Exhibition, the other being the Vršac triptych, which was commissioned by the Vršac city council.[13]

In the eyes of the clergy, Migration of the Serbs would help legitimize Serb claims to religious autonomy and partial self-administration in Austria-Hungary.[9] The official Church narrative held that Leopold had requested that the Serbs of Kosovo, Macedonia and the Sandžak settle along the Ottoman–Habsburg frontier to create a buffer against further Ottoman encroachment, and Church officials intended for Jovanović's painting to reflect this view.[14] Hence, the painting had significant political implications.[15] Habsburg Serbs asserted that the agreement between Arsenije and Leopold legitimized their claim to the lands they inhabited. Croatian nationalists decried the Serbs as "uninvited guests" who only acquired Leopold's pledge of autonomy after they had migrated to the Habsburg lands.[16] Migration of the Serbs was thus intended to challenge the historical and political narratives being forwarded by the Croatian and Hungarian painters whose works were also going to be displayed.[17]

Preparation

[edit]The commission offered Jovanović the opportunity to make a name for himself as a serious history painter, given that the subject of the work was an event of international significance and the painting was to be displayed in a foreign capital.[18] To ensure Migration of the Serbs was historically accurate, Jovanović studied authentic medieval weapons, costumes and other objects, later incorporating them into the composition.[19] He also studied medieval histories, collected ethnographical evidence and consulted historians.[18] Notably, the Church asked the historian and Orthodox priest Ilarion Ruvarac to consult Jovanović on the historical details of the migration and accompany him on a visit to the monasteries of Fruška Gora, where the young artist examined a number of contemporary sources and objects from the time.[20]

The art historian Lilien Filipovitch-Robinson notes that Jovanović incorporated modern techniques into the work and emulated the naturalistic approach of contemporary landscape painters, showing he was "at ease with the art of the past and that of his own time".[18] The composition marked a significant departure for Jovanović, who up until that point had painted mostly Orientalist pieces as opposed to ones that depicted specific moments from Serbian history.[21]

History

[edit]Original

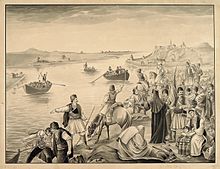

[edit]The original oil painting measures 380 by 580 centimetres (150 by 230 in).[22] It depicts Arsenije leading tens of thousands of Serbs into exile, riding a horse and flanked by a Serb flag.[2][b] In direct reference to the Bible, the image is reminiscent to that of Moses leading the chosen people out of Egypt.[24] The irony, Judah notes, is that the Patriarch is leading his people away from their promised land.[2] The Patriarch and four other figures dominate the composition, staggering unevenly across the canvas as opposed to moving in a straight line. "They punctuate the foreground," Filipovitch-Robinson writes, "directing the eye through the diagonals and curves of their bodies and gesture to the next line of figures behind them. Each subsequent line leads to the next."[25] All age groups are represented in the painting, and Jovanović pays special attention to their facial details.[26] Thousands of figures on horseback and on foot appear in the background before eventually receding into the horizon.[25] The left background shows Serbian warriors pointing their lances at the sky while the right background shows lumber wagons carrying families into exile. At the right foreground, an old man herds his sheep. To the right of the Patriarch, a mother and her infant son sit atop a horse carrying their belongings.[2] The woman is the young wife of militia leader Jovan Monasterlija and the child his son.[27] A mustachioed warrior walks before them with swords fastened to his belt and a rifle resting against his shoulder, "striding purposefully into the future". The warrior's right arm is smeared with blood and bound by a white sling.[2][c]

Upon first seeing it, Georgije was displeased by Jovanović's depiction of the exodus, particularly the sight of sheep and wagons carrying women and children, saying it made the migrants look like "rabble on the run".[29] The source of the Patriarch's displeasure lay in differing interpretations of what had originally caused the migration to take place; the Church maintained that Arsenije was simply heeding the call of the Holy Roman Emperor to head north. Having studied Ruvarac's work, Jovanović came to hold the view that fear of Ottoman persecution, rather than the desire to protect the Habsburg frontier, had prompted the migrants to leave their homes.[30] Jovanović duly took the painting back to his studio and altered it to the Patriarch's liking, removing the sheep, lumber wagons, and the woman and her infant son, putting stylized warriors in their place.[27] He also placed the letter Leopold had supposedly sent the Serbs inviting them to settle Vojvodina in the hand of Isaije Đaković, a priest riding beside Arsenije.[31] Although these changes were made relatively quickly, Jovanović could not render them in time for the painting to be displayed in Budapest.[32] Hence, only the Vršac triptych was displayed at the Millennium Exhibition.[33]

Migration of the Serbs was unveiled at the Archbishop's palace in Sremski Karlovci in 1896.[27] It was kept there until 1941, when Ustaše fascists looted the palace and stole it, cut it out of its frame and took it to Zagreb, where it remained until the end of the war. After the war, the painting was returned to Serbia, briefly put on display at Belgrade's National Museum, and then given back to the Serbian Orthodox Church. It was ultimately put on display at the patriarchate building in Belgrade, where it remains. It began undergoing restoration in 2004.[34]

Other versions

[edit]While working on the copy that the Patriarch had commissioned, Jovanović began a second version of the painting, one that retained the woman and her child, the herd of sheep and the wagons carrying refugees.[35] This, Filipovitch-Robinson asserts, is indicative of "Jovanović's firmness of conviction and artistic integrity."[25] The second version was smaller than the first, measuring 126 by 190 centimetres (50 by 75 in).[36] Like the first, it was completed in 1896, and came to be called the "Pančevo version" as it was acquired by the Pančevo Museum in the 1970s.[25] Shortly after its completion, the rights to the Pančevo version were purchased by Zagreb art collector Petar Nikolić, who secured the right to publish lithographic reproductions of the painting for the next fifty years.[37] Such prints became quite popular, and could be found in Serb homes up to the end of the 20th century.[38] As the Pančevo version was the first to be lithographically reproduced, it became the best known rendition.[25] It was displayed at the 1900 Exposition Universelle (world's fair) in Paris.[39]

At the height of World War II, Jovanović created a third version on behalf of a Belgrade physician named Darinka Smodlaka, who requested that the figure of Monasterlija's wife bear her likeness.[35][d] This version measured 65.2 by 96.5 centimetres (25.7 by 38.0 in).[40] Its current whereabouts are unknown, and it is presumed lost. In 1945, as the war neared its end, a wealthy Serbian merchant named Milenko Čavić commissioned a fourth and final version, incorrectly assuming that the others had been destroyed in the fighting. Čavić gifted the painting to the Mandukić family at the war's end. They emigrated to the United States following the communist takeover of Yugoslavia in 1945, and took it with them to New York. This version was returned to Belgrade in 2009, and is currently on display at Princess Ljubica's Residence.[35] It measures 100 by 150 centimetres (39 by 59 in).[40]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

The painting was well received in Serbia and abroad;[41] it has since attained iconic status in Serbian popular culture.[42] An allusion to it is made in Emir Kusturica's 1995 film Underground, in which war refugees are depicted marching towards Belgrade in similar fashion, following the German bombing of the city in April 1941.[43] Several authors have noted similarities between Jovanović's depiction of the migration and images of other upheavals in Serbian history. Historian Katarina Todić observes that there are striking similarities between the painting and photographs of the Royal Serbian Army's retreat to the Adriatic coast during World War I.[44]

The journalist John Kifner describes Migration of the Serbs as a "Balkan equivalent to Washington Crossing the Delaware ... an instantly recognizable [icon] of the 500-year struggle against the Ottoman Turks."[38] Professor David A. Norris, a historian specializing in Serbian culture, calls Jovanović's approach "highly effective", and writes how the stoic attitude of the priests, warriors and peasants reminds the viewer of the historical significance of the migration. He asserts that Migration of the Serbs and similar paintings stimulated a "revived collective memory" among the new Serbian middle class, "transforming ... folk memory into a more modern vehicle for the invention of a new national ideology based on the Serbian struggle for freedom from foreign domination."[45] Art historian Michele Facos describes the painting as a celebration of the Serbs' "valiant effort to defend Christian Europe against ... the Ottoman Turks."[46]

Filipovitch-Robinson ranks the painting among Jovanović's three best works, alongside The Takovo Uprising (1894) and The Proclamation of Dušan's Law Codex (1900).[47][e] This view is shared by the art historian Jelena Milojković-Djurić, as well as Judah.[41] Filipovitch-Robinson praises Jovanović's "uncompromising realism" and commends his portrayal of the migrants.[18] She writes that the Pančevo version "validates Jovanović as an insightful commentator on ... Balkan history", and is indicative of "the methodology and technical skill which had already brought him international acclaim."[25] Jovanović "persuades the viewer of the believability and authenticity of the event," she writes. "He captures the determination, strength, and dignity of a people. [...] Regardless of the reasons for this migration, they move forward in unison to meet the hard challenges of an unknown land."[26]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Seoba Srba (Serbian Cyrillic: Сеоба Срба) is how the painting is most commonly referred to in Serbian. The full title is Seoba Srba pod patriarhom Arsenijom III Crnojevićem (Migration of the Serbs under Patriarch Arsenije III Crnojević).[1]

- ^ Jovanović modeled the figure of Arsenije after Patriarch Georgije himself.[23]

- ^ Jovanović modeled the warrior after his acquaintance Nikola Igić, a judge from Vojvodina.[28]

- ^ The amount Smodlaka paid for this version is unknown.[35]

- ^ The latter is sometimes erroneously referred to as The Coronation of Tsar Dušan.[48]

References

[edit]- ^ Popovich 1999, pp. 169–171.

- ^ a b c d e Judah 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Judah 2002, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Malcolm 1998, p. 139.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 20; Lampe 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Judah 2000, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Albert 2015, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Kusovac 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Albert 2015, p. 119.

- ^ Kusovac 2009, p. 60.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 42; Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Popovich 1999, p. 170.

- ^ Miller 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2007, p. 125.

- ^ a b c d Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 43, note 25.

- ^ Milojković-Djurić 1988, pp. 17–18; Medaković 1994, p. 254.

- ^ Antić 1970, p. 31.

- ^ Petrović 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Medaković 1994, p. 254; Kusovac 2009, p. 136.

- ^ Popovich 1999, pp. 170–171; Segesten 2011, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c d e f Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 43.

- ^ a b Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Milojković-Djurić 1988, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Kusovac 2009, p. 136.

- ^ Judah 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 43; Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 60, note 60.

- ^ Medaković 1994, p. 254.

- ^ Milojković-Djurić 1988, pp. 17–18; Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 43, note 22.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 61, note 68.

- ^ "Restoration of Paja Jovanović's Famous Masterpiece "The Migration of the Serbs" Begins". Serbian Orthodox Church. 18 August 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Četiri originala "Seobe Srba"" (in Serbian). Politika. 15 September 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2008, p. 43; Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Kusovac 2009, p. 138.

- ^ a b Kifner, John (10 April 1994). "Through the Serbian Mind's Eye". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2005, p. 324.

- ^ a b Petrović 2012, p. 69.

- ^ a b Milojković-Djurić 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Kusovac 2009, p. 133; Segesten 2011, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Browne 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Todić 2014, p. 446.

- ^ Norris 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Facos 2011, p. 393.

- ^ Filipovitch-Robinson 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Antić 1970, p. 18.

Bibliography

[edit]- Albert, Samuel D. (2015). "The Nation For Itself: The 1896 Hungarian Millennium and the 1906 Bucharest National General Exhibition". In Petrová, Marta (ed.). Cultures of International Exhibitions 1840–1940: Great Exhibitions in the Margins. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 113–37. ISBN 978-1-4724-3281-0.

- Antić, Radmila (1970). Paja Jovanović. Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Belgrade City Museum. OCLC 18028481.

- Browne, Dennis (2013). "Emir Kusturica: "Underground" and "Life is a Miracle"". In Kazecki, Jakub; Ritzenhoff, Karen A.; Miller, Cynthia J. (eds.). Border Visions: Identity and Diaspora in Film. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-9051-0.

- Facos, Michelle (2011). An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-84071-5.

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2005). "Inspiration and Affirmation of Revolution in Nineteenth-Century Serbian Painting" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 19 (2). Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers: 317–28. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2016.

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2007). "Exploring Modernity in the Art of Krstić, Jovanović and Predić" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 21 (1). Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers: 115–35. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2008). "Paja Jovanović and the Imagining of War and Peace" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 22 (1). Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers: 35–53. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015.

- Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien (2014). "From Tradition to Modernism: Uroš Predić and Paja Jovanović". In Bogdanović, Jelena; Filipovitch-Robinson, Lilien; Marjanović, Igor (eds.). On the Very Edge: Modernism and Modernity in the Arts and Architecture of Interwar Serbia (1918–1941). Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press. pp. 31–63. ISBN 978-90-5867-993-2.

- Judah, Tim (1999). "The Serbs: The Sweet and Rotten Smell of History". In Graubard, Stephen Richards (ed.). A New Europe for the Old?. Piscataway, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 23–47. ISBN 978-1-4128-1617-5.

- Judah, Tim (2000) [1997]. The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (2nd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.

- Judah, Tim (2002). Kosovo: War and Revenge. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09725-2.

- Kusovac, Nikola (2009). Паја Јовановић [Paja Jovanović] (in Serbian). Belgrade: National Museum of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-80619-55-2.

- Lampe, John R. (2000) [1996]. Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-66613-5.

- Medaković, Dejan (1994). Srpski slikari XVIII–XX veka: Likovi i dela [Serbian Painters, 18th–20th century: Portraits and Works] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Prosveta. ISBN 978-86-07-00757-8.

- Miller, Nicholas J. (1997). Between Nation and State: Serbian Politics in Croatia Before the First World War. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822939894.

- Milojković-Djurić, Jelena (1988). Tradition and Avant-Garde: Literature and Art in Serbian Culture, 1900–1918. Vol. 1. Boulder, Colorado: Eastern European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-131-9.

- Norris, David A. (2008). Belgrade: A Cultural History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-970452-1.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History of an Idea. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6708-5.

- Petrović, Petar (2012). Паја Јовановић: Систематски каталог дела [Paja Jovanović: A Systematic Catalogue of His Works] (in Serbian). Belgrade: National Museum of Serbia. ISBN 978-86-7269-130-6.

- Popovich, Ljubica (1999). "Internationalism and Ethnicity: A Case Study of Serbian Painting" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 13 (1). Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers: 160–85. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2016.

- Segesten, Anamaria Dutceac (2011). Myth, Identity and Conflict: A Comparative Analysis of Romanian and Serbian Textbooks. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-4867-9.

- Todić, Katarina (2014). "In the Name of Father and Son: Remembering the First World War in Serbia". In Bürgschwenter, Joachim; Egger, Matthias; Barth-Scalmani, Gunda (eds.). Other Fronts, Other Wars? First World War Studies on the Eve of the Centennial. Leiden, Netherlands: BRILL. pp. 437–63. ISBN 978-90-04-27951-3.