Old Serbia

Old Serbia (Serbian: Стара Србија, romanized: Stara Srbija) is a Serbian historiographical term[1] that is used to describe the territory that according to the dominant school of Serbian historiography in the late 19th century formed the core of the Serbian Empire in 1346–71.[2][3]

The term does not refer to a defined region but over time in the late 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century it came to include the regions of Raška, Kosovo and Metohija and much of modern North Macedonia.[4][3] The term Old Serbians (Serbian: Старосрбијанци, romanized: Starosrbijanci) were used as designations by Serb authors and later governments for Slavic populations from regions such as Vardar Macedonia.[5] In modern historiography, the concept of Old Serbia as it developed in the 19th century has been criticised as a historical myth, based often on invented or tendentiously interpreted historical events.[3]

Terminology

[edit]Vuk Stefanović Karadžić referred to "Old Serbia" as a territory of the Serb people that was part of medieval Serbia prior to the Ottoman conquest.[6] Milovan Radovanović claims that although the term was not attested until the 19th century it emerged in the colloquial speech of the Serb population[7] who lived in territories of the Habsburg monarchy after the Great Migrations.

The toponym first appeared in the public sphere during the 1860s, the time of the triumph of Vuk Karadžić's ideas. Until then the Serbs imagined the borders of their country spreading northwest.[8] These ideas are grounded in the late-19th-century Serbian nationalism and changed the goal of Serbia's territorial expansion from the west to the south and were important to Serbian nationalism during the Balkan Wars and the First World War.

History

[edit]In the early nineteenth century, Old Serbia as a concept was introduced by Vuk Karadžić in his ethnographic, geographic and historical publications.[9] Karadžić defined Old Serbia as including the Morava-Vardar river valley.[10] In particular, it comprised the Kriva and Pčinja rivers, the area of the Bregalnica river, the northern zone of the river Vardar, and a section of the Morava river.[10] For Karadžić, the Slavic inhabitants of Macedonia were Serbian, detached from its Serb past due to Ottoman rule and propaganda activities undertaken by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.[10] The term Old Serbia was used in literature and from the 1830s onward, its usage widened and denoted a particular area that was not part of the Principality of Serbia.[11]

After its appearance during the 1860s, the term denoted only Raška.[12] Following the Serbian–Ottoman Wars (1876–1878), several authors began to represent the term Old Serbia as synonymous with the Ottoman Vilayet of Kosovo.[11] From 1878 onward, the Serbian state started saying "Old Serbia" also included Kosovo.[13] By 1912, the claims were narrowed to Kosovo only.[13] The critical treatment of facts was damaged by the invocation of the past for the justification of present and future claims, and by the mixture of history and contemporary issues.[14] The core myth of Serbian identity became the idea Kosovo was the cradle of the Serbian nation.[12] Serbian rebels of the First Serbian Uprising and Second Serbian Uprising had no territorial ambitions over Kosovo.[15] A plan made during that period to create a Slav-Serbian empire in the Serb-inhabited areas of the Ottoman Empire excluded Kosovo and Old Serbia.[15]

Serbian interest in the region of Macedonia was defined in a foreign policy program named Načertanije.[16] It was a document whose author Ilija Garašanin, a Serb politician envisioned a Serbian state that included the Principality of Serbia and territories such as Bosnia, Herzegovina, Montenegro and Old Serbia.[16] Garašanin in Načertanije was not clear about the southern confines of this larger state[16] and neither was Kosovo nor Old Serbia mentioned directly.[17] This program responded to the need to spread propaganda among Serbs within the Ottoman Empire.[16]

Serbian engagement with the region started in 1868 with the establishment of the Educational Council (Prosvetni odbor) that opened schools and sent Serb instructors and textbooks to Macedonia and Old Serbia.[18] In May 1877 a delegation of Serbs of Old Serbia presented their request to 'liberate' and unite Old Serbia with the Principality of Serbia to the government of Serbia.[19] They also informed representatives of the Great Powers and the Emperor of Russia about their demands.[19] In the same year the Committee for the Liberation of Old Serbia and Macedonia was founded.[20]

Serbian nationalists envisioned Serbia as a "Piedmont of the Balkans" that would unify certain territories they interpreted as Serbian in the region into one state, like Old Serbia.[22] In the 1877 peace after the Serbian–Ottoman Wars (1876–1878), the Serbs hoped to gain the Kosovo Vilayet and Sanjak of Novi Pazar to the Lim River.[23] With the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, Serbia received full sovereignty and made territorial gains around this time, acquiring the districts of Niš, Pirot, Vranje and Toplica.[23][24]

Following the Great Eastern Crisis (1875–1878) and the emergence of the Macedonian Question, Serbs were dissatisfied that Bulgaria became a rival for the region of Macedonia or "Old Serbia".[25][26] Kosovo formed part of the Kosovo myth that prior to those events was viewed in spiritual and ethical terms, and an important aspect of Serbian cultural and ordinary life.[27][28] By the 1880s, Serbia saw those areas, referred to as Old Serbia, in territorial terms.[27] The relationship with Austria-Hungary following 1881 considerably affected the Serbian state that moved it to concentrate its regional efforts toward a southerly direction.[29][30] At this time, Old Serbia became integrated into the Serbian state's collective narrative about its own self identity.[27]

A process began in the same decade in Serbia, where diplomacy and foreign policy were deployed to expand Serb influence in Old Serbia, to gather data about the mainly unknown territory and make preparations for future armed conflict with the Ottoman Empire.[27] As such, Guidelines for Establishing Serbia's Influence in Macedonia and Old Serbia were made part of the Serbian government platform in 1887.[27] Over several years, a number of consulates were opened by the Serbian state in Salonika, Skopje, Bitola and Pristina and included consuls such as Milan Rakić and Branislav Nušić who chronicled the difficult security circumstances of Serbs in the Ottoman Empire.[27]

Serbia also used education policy in Old Serbia to advance sentiments of a strong national identification among Orthodox inhabitants to the Serbian state.[27] To bolster Serbian influence in Old Serbia, the St. Sava Society was established (1886) to educate aspiring teachers for the task, and later a department was created in the Serbian Education Ministry with a near identical objective.[31] Starting from 1903, the Serbian political establishment altered the policy for Macedonia and Old Serbia.[29] The focus switched from education propaganda toward providing Serbs in the region with arms resulting by 1904 in Chetnik bands and armed irregulars operating in Macedonia.[29]

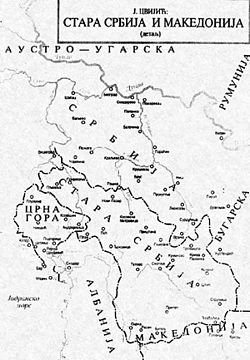

The majority of efforts to include Old Serbia into newer Serb discourses on Serbdom and the larger narrative about Serbia was undertaken by people outside the bounds of the Serb state, such as artists, composers, writers, scientists and other members of the intelligentsia.[31] A prominent example was Jovan Cvijić, a Serb academic who made ethnographic maps depicting the Balkans that aimed to advance Serb claims to Kosovo and his publications influenced later generations of historiographers.[31][10] Cvijić defined Old Serbia as including Kosovo and Metohija, spanning southward and encompassing Debar, Kumanovo, Prilep and Tetovo.[32][33] In 1906–1907, Cvijić wrote the Macedonian Slavs were an "amorphous" and "floating mass", and lacked national identity.[32][10] By regarding northern Macedonia as "Old Serbia", he sought to legitimize Serbia's territorial claims over the territory.[32] Cvijić continuously changed his maps to include or exclude "Macedonian Slavs", altering the location of the boundary between Bulgarians and Serbs and readjusting the colour scheme to show Macedonia as nearer to Serbia.[34]

Ethnographic maps showing the Macedonian region and Old Serbia were part of a wider conflict involving similar competing maps of the region that was played out on the international scene.[35] The ethnographic maps attempted to show and affirm various national perspectives and solutions offered by their authors, like mapping and classifying peoples according to their definitions or new borders, to geopolitical questions in the Balkans.[35] Due to Greek and Serbian cooperation, northerly areas centred around Skopje were not shown in their maps as being part of Macedonia, as Serbia regarded those areas as Old Serbia.[36] Serb authors viewed the Slavic inhabitants of Macedonia as Old Serbians or Southern Serbs, designations that were used more in the past than in modern times.[37]

Old Serbia as a term evoked strong symbolism and message regarding Serb historical rights to the land whose demographics were seen to have been altered in the Ottoman period to favour Albanians at the conclusion of the seventeenth century.[29] Theories advanced at the time like those by Cvijić referred to the Albanians in the area as a result of metastasis and due to a "great Albanian campaign to the east".[29] The more prominent theory stated that Ottoman aims were to split the Serbian principality from Old Serbia that involved installing Muslim Albanians into the area.[29] It claimed that the evidence lay in the settlement pattern of Albanians as dispersed and not compact.[29] The theory concluded that Serbian abilities were diminished for liberation wars of the future as Albanians formed a "living wall" spanning from Kosovo to the Pĉinja area, limiting the spread of Serb influence.[29] As a result of the Serbian-Ottoman war, the Albanian inhabited area shrank after they were expelled from the Toplica and Morava valleys by the Serbian army in 1878.[29]

Before the events of the Berlin Congress, only a small number of Serbian accounts existed that described Old Serbia and Macedonia in the early nineteenth century.[28] Old Serbia became a topic of focus (mid nineteenth - early twentieth centuries) in Serbian travelogues by Serb authors[a] from Serbia and Austria-Hungary.[38] In the aftermath of the Serbo-Bulgarian War (1885), several travelogues were published on Old Serbia by politicians and intellectuals seeking to counter "Bulgarian propaganda".[39]

The travel accounts through use of geography, history, philology and ethnography sought to bolster nationalist claims that those lands were for the Serbs.[40] Focusing on language and cultural aspects, the travellers sought to present and connect the Serbs of Serbia and Austria-Hungary to the inhabitants of Old Serbia as synonymous and one nation that lacked differences.[34] Many realities of the day were bypassed such as interpreting demographics in an unclear or doubtful manner, or by digressing through subjects of geography and history.[34]

Travels through Old Serbia were presented as a movement through time and observations by writers focused on the medieval period and landscape geography, as opposed to the reality of the day.[41] These accounts contained portrayals and metaphors about Serb travellers in danger encountering the national cultural extinction of local Serbs or biological threats.[42][43] The links travelogues drew to Old Serbia with inhabitants under threat had an important impact through discourse in connecting an emerging Serb national identity with Kosovo.[42]

Serb travelogues defined Old Serbia in its minimum extent as being Kosovo and at its wider range as encompassing north western Macedonia and northern Albania.[44] Travellers writing about Macedonia used cultural and socio-linguistic depictions to state that local Christian Slavic inhabitants were exposed to Bulgarian propaganda that inhibited their ability to become Serbian.[44] Efforts were devoted to interpreting linguistic and cultural information to present Macedonians as nearer to the Serbs than Bulgarians.[34] These included focusing on local customs in the area like family saint days and regarding them as part of similar traditions (Slava) in Serbia.[45] Local traditional songs and epic poetry were scrutinised to met the criteria of being classified Serbian, not Bulgarian, such as folklore about medieval Prince Marko were deemed as examples of Serbian culture.[45] Due to competition from the Bulgarian national movement, efforts were devoted to delineate a boundary in areas where differences among religions were nonexistent.[46]

-

Novo Brdo Fortress, a medieval Serbian fortress in Kosovo

-

Patriarchal Monastery of Peć in Kosovo, the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Church from the 14th century when its status was upgraded into a patriarchate, today a UNESCO World Heritage Site

In areas where the population was mainly Albanian, the appropriation undertaken by travel writers was reinforced through narratives of history, positions based on economic and geographic issues, at times that involved fabricating information and creating the room for discrimination on cultural and racial grounds toward non-Slavs.[47] It would entail presenting non Orthodox Slavic inhabitants as either recent religious converts, immigrants or people who underwent a language shift.[34] Peoples like the Turks, Turkifed inhabitants and Albanians (in several texts called "Arnauts") were portrayed as converted inhabitants who were former Serbs.[48] The process allowed the lands of Old Serbia to be denoted as Serbian and implied a future removal of political rights and ability for self determination from non-Slavic inhabitants such as Albanians, whom were viewed as the cultural and racial "other", unhygienic, and a danger.[49] As travelogues were presented as firsthand accounts and truth, their contents aimed to get a reader to react and identify as a person with the imagined community of a nation.[50]

At the same time, songs from oral traditions, collected and catalogued from Macedonia and Kosovo (Old Serbia) began to be played in Serbia and were reworked by modern Serbian composers into Serb songs through the addition of then contemporary musical European styles.[42] Kosovo, which was listed as "Old Serbia", was classified as an "unredeemed Serbian" region by the Black Hand, a secret society formed by Serb officers that generated nationalist material and armed activity by bands outside Serbia.[51]

In Serbian historiography, the First Balkan War (1912–1913) is also known as War for Liberation of Old Serbia.[citation needed] Later, in 1913 the Sandžak, Kosovo and Metohija and Vardar Macedonia became part of the Kingdom of Serbia. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Serb publications aiming to counter Albanian interests and to justify Serbian historical claims in Kosovo and Macedonia through the recreation of Old Serbia in those territories appeared.[52] The acquisition of new lands was interpreted by individuals such as Vaso Čubrilović, a Serb intellectual, as the realisation of Garašanin's concept.[53] In 1914, groups within the Serbian army expressed dissatisfaction with certain elements of civilian governance in Old Serbia (Macedonia) and sought to undermine the Serb government by aiding a plot to kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne.[54]

At the end of the First World War, Serbia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the state placed its efforts toward speeding up the incorporation of newly acquired lands such as Kosovo, Macedonia and Sandžak.[53] These areas deemed as Old Serbia were subsequently organised into a province (pokrajina) that was given the official name of South Serbia.[53][55] To integrate the region after perceived centuries of "separation" between the area and Serbia, national, cultural and economic considerations were seen as a centre of focus in Old Serbia for some high ranking Serb officials.[56] Institutions were founded to accelerate the regional economy such as a prominent bank in Skopje (1923) named "Old Serbia".[57] The government of Nikola Pašić treated the Slavic population of Vardar Macedonia as either Serbs or as Old Serbians (Starosrbijanci).[58] Following the Second World War, Yugoslavia was reorganised as a federal state, with Serbia as one of six republics.[59] Serbia was most affected by the internal territorial changes as it lost control of what had been defined as Old Serbia, which became the separate republic of Macedonia.[59]

The stances and opinions of the early twentieth century Serbian intelligentsia have left a legacy in the political space as those views are used in modern discourses of Serb nationalism to uphold nationalistic claims.[50] Travelogues have been republished and often lack critical analysis of the period in which they were written. This also applies to some materials such as often inaccurate "ethnic maps", that have been re-proposed in some modern academic publications by Serbian authors.[50]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^

Serb travelogues and their authors are:[60]

- Gedeon Josif Jurišić (1852): Dečanski Prevenac [Dečani's Pathfinder]

- Miloš S. Milojević (1871–1877): Putopis dela prave (Stare) Srbije [Travelogue through a Portion of (Old) Serbia]

- Panta Srećković (1875–1882): Putničke slike (Kosovo; Familijarna grobnica Mrnjavčevića; Podrim i Metohija) [Journey Images (Kosovo; Tomb of the Mrnjavčević Family; Podrim and Metohija]

- Vladimir Karić (1889): Carigrad, Sveta Gora, Solun. Putničke crtice s beleškama o narodnoj propagandi na Istoku [Constantinople, Mount Athos, Thessaloniki. Travel Sketches with Notes about Traditional Customs of the East]

- Spiridon Gopčević (1890): Stara Srbija i Makedonija. Moj putni izveštaj [Old Serbia and Macedonia. My Travel Report]

- Stojan Novaković (1892): S Morave na Vardar: 1886. Putne beleške [From the Morava to Vardar: 1886. Travel Notes]

- Spira Kalik (1894): Iz Beograda u Solun i Skoplje s Beogradskim pevačkim društvom putničke beleške [From Belgrade to Thessaloniki and Skopje with the Belgrade Singing Society: Traveller's Notes]

- Branislav Nušić (1894): S obala Ohridskog jezera [From the Banks of Lake Ohrid]

- Milojko V. Veselinović (1895): Pogled kroz Kosovo [A view of Kosovo]

- Branislav Nušić (1892–1902): S Kosova na sinje more [From Kosovo to Open Sea]

- Ivan Nušić (1895): Pogled kriz Kosovo [A view of Kosovo]

- Ivan Ivanić (1903): Na Kosovu: Sa Šara, po Kosovu, na Zvečan. Iz putnih beležaka Ivana Ivanića [In Kosovo: From Šar through Kosovo, to Zvečan. The Travel Notes of Ivan Ivanić]

- Ivan Ivanić (1906–1908): Maćedonija i Macedonći. Putopisne beleške [Macedonia and Macedonians. Travel Notes]

- Todor P. Stanković (1910): Putne beleške po Staroj Srbiji: 1871-1898 [Travel Notes from Old Serbia 1871-1898]

References

[edit]- ^ Milovan Radovanović (2004). Etnički i demografski procesi na Kosovu i Metohiji. Liber Press. p. 33. ISBN 9788675560180. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ Dedijer, Jevto (2000) [1998]. "Stara Srbija". Давидовић.

- ^ a b c Atanasovski 2019, p. 34

- ^ Ivo Banač (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0801494932. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ Marinov 2013, pp. 275, 324.

- ^ Vladimir Stojančević (1988). Vuk Karadžić i njegovo doba: rasprave i članci. Zavod za udžbenike i nastavna sredstva.

- ^ Milovan Radovanović (2004). Etnički i demografski procesi na Kosovu i Metohiji. Liber Press. p. 38. ISBN 9788675560180. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ Andrew Light, Jonathan M. Smith as ed., Philosophy and Geography II: The Production of Public Space, Rowman & Littlefield, 1998, ISBN 0847688100, p. 241.

- ^ Vučetić 2018, pp. 242–243.

- ^ a b c d e Vučetić 2018, p. 243

- ^ a b Jovanović 2019, p. 39.

- ^ a b Rama 2019, p. 76.

- ^ a b Rama, Shinasi A. (2019). Nation Failure, Ethnic Elites, and Balance of Power: The International Administration of Kosova. Springer. pp. 76, 80–81. ISBN 9783030051921.

- ^ Madgearu, Alexandru; Gordon, Martin (2008). The Wars of the Balkan Peninsula: Their Medieval Origins. Scarecrow Press. pp. 175. ISBN 9780810858466.

Stara Srbija.

- ^ a b Ejdus 2019, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c d Vučetić 2018, p. 236.

- ^ Ejdus 2019, p. 46.

- ^ Rossos, Andrew (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A history. Hoover Press. p. 275. ISBN 9780817948832.

- ^ a b Mitrović, Andrej (1996). Stojanu Novakoviću u spomen: o osamdesetogodišnjici smrti. Srpska književna zadruga. p. 68. ISBN 9788637906247. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Dragoslav Srejović; Slavko Gavrilović; Sima M. Ćirković (1983). Istorija srpskog naroda: knj. Od Berlinskog kongresa do Ujedinjenja 1878-1918 (2 v.). Srpska književna zadruga. p. 291. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Yosmaolğu, Ipek K. (2010). "Constructing national identity in Ottoman Macedonia". In Zartman, I. William (ed.). Understanding life in the borderlands: Boundaries in depth and in motion. University of Georgia Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780820336145.

- ^ Jelavich 1983, p. 109.

- ^ a b Jelavich 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Ejdus 2019, p. 48.

- ^ Crampton 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Vučetić 2018, p. 237.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ejdus 2019, p. 49.

- ^ a b Atanasovski 2019, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jovanović 2019, p. 40.

- ^ Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780521274593.

- ^ a b c Ejdus 2019, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Marinov 2013, p. 315.

- ^ Vučetić, Biljana (2018). "Serbia and the Macedonian Question: The intertwining of Politics and Science". In Motta, Giuseppe (ed.). Dynamics and Policies of Prejudice from the Eighteenth to the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 243–244. ISBN 9781527517004.

- ^ a b c d e Atanasovski 2019, p. 33.

- ^ a b Atanasovski 2019, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Marinov 2013, p. 298.

- ^ Marinov 2013, p. 275.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, p. 24.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 22, 26, 33–34.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 26–27, 33.

- ^ a b c Ejdus, Filip (2019). Crisis and Ontological Insecurity: Serbia's Anxiety over Kosovo's Secession. Springer. p. 51. ISBN 9783030206673.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b Atanasovski2019, p. 22.

- ^ a b Atanasovski 2019, p. 31.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, p. 30.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 22–23, 33–34.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Atanasovski 2019, pp. 33–34.

- ^ a b c Atanasovski 2019, p. 34.

- ^ Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2003). "Serbia, Montenegro and Yugoslavia". In Djokić, Dejan (ed.). Yugoslavism: Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 9781850656630.

- ^ Jovanović, Vladan (2018). "The Savages Attack from Behind: Anthropological Stereotypes about Albanians in Serbian Public Discourse". In Motta, Giuseppe (ed.). Dynamics and Policies of Prejudice from the Eighteenth to the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 258–259. ISBN 9781527517004.

- ^ a b c Jovanović, Vladan (2019). ""Reconquista of Old Serbia": On the continuity of territorial and demographic policy in Kosovo". In Pavlović, Aleksandar; Draško, Gazela Pudar; Halili, Rigels (eds.). Rethinking Serbian-Albanian Relations: Figuring out the Enemy. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 9781351273145.

- ^ Crampton, Richard J. (2003). Eastern Europe in the twentieth century–and after. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781134712229.

- ^ Boškovska 2017, pp. 31, 101.

- ^ Boškovska, Nada (2017). Yugoslavia and Macedonia Before Tito: Between Repression and Integration. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 9781786730732.

- ^ "Banka 'Stara Srbija AD' u Skoplju između dva svetska rata". scindeks.nb.rs. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06.

- ^ Marinov 2013, p. 324.

- ^ a b Marinov, Tchavdar (2013). "Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism". In Daskalov, Roumen; Marinov, Tchavdar (eds.). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. Brill. p. 381. ISBN 9789004250765.

- ^ Atanasovski, Srđan (2019). ""Producing Old Serbia: In the footsteps of travel writers on the path of folklore". In Pavlović, Aleksandar; Draško, Gazela Pudar; Halili, Rigels (eds.). Rethinking Serbian-Albanian Relations: Figuring out the Enemy. Routledge. pp. 23, 25. ISBN 9781351273145.

Serb Travelogues and associated material

[edit]- Miloš S Milojević (1871). Putopis dela prave (stare) Srbije. U Državnoj štampariji. (Public domain)

- Gopčević, Spiridion (1890). Stara Srbija i Makedonija. Beograd, Parna štamparija D. Dimitrijevića. (Public domain)

- Jovan Hadži-Vasiljević (1906). Stara Srbija i Maćedonija: sa gledišta geografskog, istorijskog i političkog. Štamp. D. Dimitrijevića.

- Todor P. Stanković (1910). Putne beleške po staroj Srbiji, 1871-1898. Beograd : Stamparija D. Muncá i M. Karića. (Public domain)

- Ѳ. М Бацетич; Добрило Аранитовић (2001). Стара Србија: прошлост, садашњост, народни живот и обичаји. Историјски музеј Србије.

- Мирчета Вемић (2005). Етничка карта дела Старе Србије: Према путопису Милоша С. Милојевића 1871–1877. год. Geografski institut „Jovan Cvijić“ SANU. ISBN 978-86-80029-29-0.

- Spiridion Gopčević (2008). Стара Србија и Македонија: фототипско издање. Народна и универзитетска библиотека "Иво Андрић" Приштина. ISBN 978-86-7935-113-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Raičević, Svetozar (1933). "Etnološke beleške iz Južne Srbije". Narodna starina. 12 (32): 279–284.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Jagodić, Miloš. "Планови o политици Србије према Старој Србији и Македонији (1878–1885)." Историјски часопис 60 (2011): 435–460.

- Zarković, V. (2011). "The work of Serbian diplomacy on the protection of Serbs in old Serbia in the last decade of the 19th century" (PDF). Baština (30): 105–116.

- Црквене прилике у Старој Србији од укидања Пећке патријаршије до Велике источне кризе (1766–1878), у: Историја и значај Призренске богословије : (поводом 140 годишњице од оснивања). - Ниш : Филозофски факултет : Призренска богословија Св. Кирила и Методија : Центар за црквене студије, 2013, 9-29.

- Vladimir D. Vučković (2014). Stara Srbija i Makedonija: oslobođenje i uređenje. Medivest KT. ISBN 978-86-88415-52-1.

- Jagodić, Miloš. "Извештај Василија Ђорђевића о догађајима у Старој Србији из јула 1854." Мешовита грађа 36 (2015): 195–206.

- Šešum, Uroš S. (2016). "Србија и Стара Србија: (1804-1839)" (Document). Универзитет у Београду, Филозофски факултет.

- Šćekić, Radenko, Žarko Leković, and Marijan Premović. "Political Developments and Unrests in Stara Raška (Old Rascia) and Old Herzegovina during Ottoman Rule." Balcanica XLVI (2015): 79-106.

- NEDELJKOVIĆ, SLAVIŠA. "BETWEEN THE IMPERIAL GOVERNMENT AND REBELS (Old Serbia during the rebellion of the Shkodra Pasha Mustafa Bushati and the Bosnian aristocracy 1830–1832)." Istraživanja: Journal of Historical Researches 26 (2016): 91-105.

External links

[edit]