Palo Alto, California

Palo Alto, California | |

|---|---|

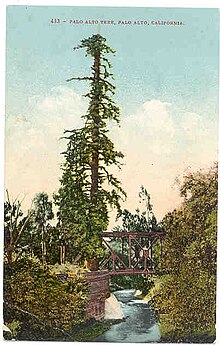

| Etymology: from Spanish palo alto 'tall stick' | |

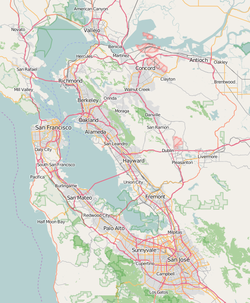

Location in Santa Clara County and California | |

| Coordinates: 37°25′45″N 122°8′17″W / 37.42917°N 122.13806°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Santa Clara |

| Incorporated | April 23, 1894[1] |

| Named for | El Palo Alto |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Body | City council members:[2]

|

| • Mayor | Greer Stone |

| Area | |

• Total | 26.00 sq mi (67.35 km2) |

| • Land | 24.10 sq mi (62.41 km2) |

| • Water | 1.91 sq mi (4.94 km2) 7.38% |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 68,572 |

| • Density | 2,871.52/sq mi (1,047.35/km2) |

| Demonym | Palo Altan |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 94301-94306 & 94309 |

| Area code | 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-55282 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277572, 2411362 |

| Website | cityofpaloalto |

Palo Alto (/ˌpæloʊ ˈæltoʊ/ PAL-oh AL-toh; Spanish for 'tall stick') is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city of Palo Alto was established in 1894 by the American industrialist Leland Stanford when he founded Stanford University in memory of his son, Leland Stanford Jr. Palo Alto later expanded and now borders East Palo Alto, Mountain View, Los Altos, Los Altos Hills, Stanford, Portola Valley, and Menlo Park. As of the 2020 census, the population was 68,572.[5] Palo Alto has one of the highest costs of living in the United States,[6][7] and its residents are among the most educated in the country. However, it has a youth suicide rate four times higher than the national average, often attributed to academic pressure.[8]

As one of the principal cities of Silicon Valley, Palo Alto is home to the headquarters of multiple tech companies, including HP, Space Systems/Loral, VMware, and PARC. Palo Alto has also served as headquarters or the founding location of several other tech companies, including Apple,[9] Google,[10] Facebook, Logitech,[11] Tesla,[12] Intuit, IDEO, Pinterest, and PayPal. Ford Motor Company and Lockheed Martin each additionally maintain major research and technology facilities within Palo Alto.[13][14]

History

[edit]

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Ohlone lived on the San Francisco peninsula; in particular, the Puichon Ohlone lived in the Palo Alto area. The area of modern Palo Alto was first recorded by the 1769 party of Gaspar de Portolá, a 64-man, 200-horse expedition setting out from San Diego to find Monterey Bay.[15] The group trekked past the bay without recognizing it and continued north. When they reached modern-day Pacifica, they ascended Sweeney Ridge and saw the San Francisco Bay on November 2.[15] Portolá descended from Sweeney Ridge southeast down San Andreas Creek to Laguna Creek (now Crystal Springs Reservoir), thence to the San Francisquito Creek watershed, ultimately camping from November 6–11, 1769, by a tall redwood later to be known as El Palo Alto.[15]

In 1777, Father Junipero Serra established the Mission Santa Clara de Asis, whose northern boundary was San Francisquito Creek and whose lands included modern Palo Alto. The area was under the control of the viceroy of Mexico and ultimately under the control of Spain. On November 29, 1777, Pueblo de San Jose de Guadalupe (now the city of San Jose a few miles to the south of what was to be Palo Alto) was established by order of the viceroy despite the displeasure of the local mission. The Mexican War of Independence ending in 1821 led to Mexico becoming an independent country, though San Jose did not recognize rule by the new Mexico until May 10, 1825. Mexico proceeded to sell off or grant much of the mission land.[16]

During the Mexican–American War, the United States seized Alta California in 1846; however, this was not legalized until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on July 4, 1848. Mexican citizens in the area could choose to become United States citizens and their land grants were to be recognized if they chose to do so (though many legal disputes arose over this).[citation needed]

The land grant, Rancho Rinconada del Arroyo de San Francisquito, of about 2,230 acres (9.0 km2) on the lower reaches of San Francisquito Creek (i.e., parts of modern Menlo Park and northern Palo Alto) was given to Maria Antonia Mesa in 1841. She and her husband Rafael Soto (who had died in 1839) had settled in 1835 near present-day Newell and Middlefield roads and sold supplies. In 1839, their daughter María Luisa Soto (1817–1883) married John Coppinger, who was to be, in 1841, the grantee of Rancho Cañada de Raymundo (in modern San Mateo county). Upon Coppinger's death in 1847, Maria inherited it and later married a visiting boat captain, John Greer. Greer owned a home on the site that is now Town & Country Village on Embarcadero and El Camino Real. Greer Avenue and Court are named for him.[citation needed]

To the south of the Sotos, the brothers Secundino and Teodoro Robles in 1849 bought Rancho Rincon de San Francisquito from José Peña, the 1841 grantee.[17] The grant covered the area south of Rancho Rinconada del Arroyo de San Francisquito to more or less present-day Mountain View. The grant was bounded on the south by Mariano Castro's Rancho Pastoria de las Borregas grant across San Antonio Road. This later became the Robles Rancho, which constitutes about 80% of Palo Alto and Stanford University today. In 1863, it was whittled down in the courts to 6,981 acres (28.25 km2). Stories say the grand hacienda was built on the former meager adobe of José Peña near Ferne off San Antonio Road, midway between Middlefield and Alma Street.[18] Their hacienda hosted fiestas and bull fights. It was ruined in the 1906 earthquake and its lumber was used to build a large barn nearby, which was said to have lingered until the early 1950s. On April 10, 1853, 250 acres (1.0 km2), comprising the present-day Barron Park, Matadero Creek and Stanford Business Park, was sold for $2,000 to Elisha Oscar Crosby, who called his new property Mayfield Farm. The name of Mayfield was later attached to the community that started nearby. On September 23, 1856, the Crosby land was transferred to Sarah Wallis to satisfy a debt he owed her.[19] In 1880, Secundino Robles, father to twenty-nine children, still lived just south of Palo Alto, near the location of the present-day San Antonio Shopping Center in Mountain View.[citation needed]

Many of the Spanish names in the Palo Alto area represent the local heritage, descriptive terms, and former residents. Pena Court, Miranda Avenue, which was essentially Foothill Expressway, was the married name of Juana Briones and the name occurs in Courts and Avenues and other street names in Palo Alto and Mountain View in the quadrant where she owned vast areas between Stanford University, Grant Road in Mountain View and west of El Camino Real. Yerba Buena was to her credit. Rinconada was the major Mexican land grant name.[citation needed]

The township of Mayfield was formed in 1855, around the site of a stagecoach stop and saloon known as "Uncle Jim's Cabin" near the intersection of El Camino Real and today's California Avenue in what is now southern Palo Alto.[20] In October 1863 the San Francisco to San Jose railroad had been built as far as Mayfield and service started between San Francisco and Mayfield (the station is now California Avenue); train service all the way to San Jose started in January 1864.[21][22] El Camino became Main Street; the northeast–southwest cross streets were named for Civil War heroes, with California Avenue originally being Lincoln Street. The town had its own newspaper by 1869 (the Mayfield Enterprise, in English and Spanish), incorporated in 1903, and had breweries and a cannery.[20]

In 1875, French financier Jean Baptiste Paulin Caperon, better known as Peter Coutts, purchased land in Mayfield and four other parcels around three sides of today's College Terrace – more than a thousand acres (4.0 km2) extending from today's Page Mill Road to Serra Street and from El Camino Real to the foothills. Coutts named his property Ayrshire Farm. His fanciful 50-foot-tall (15 m) brick tower near Matadero Creek likely marked the south corner of his property. Leland Stanford started buying land in the area in 1876 for a horse farm, called the Palo Alto Stock Farm. Stanford bought Ayrshire Farm in 1882.[23]

Creation of the town

[edit]

In 1884, Leland Stanford and his wife, Jane lost their only child Leland Stanford Jr. when he died of typhoid fever at age 15 and decided to create a university in his memory. In 1886, they proposed having the university's gateway be Mayfield. However, they had one condition: alcohol had to be banned from the town. Known for its 13 rowdy saloons, Mayfield rejected his request. This led them to drive the formation of a new temperance town with the help of their friend Timothy Hopkins of the Southern Pacific Railroad, who in 1887 bought 740 acres (3.0 km2) of private land for the new townsite. This Hopkins Tract, bounded by El Camino Real, San Francisquito Creek, Boyce, Channing, Melville, and Hopkins Avenues, and Embarcadero Road,[24] was proclaimed a local Heritage District during Palo Alto's centennial in 1994. The Stanfords set up their university, Stanford University, and a train stop (on University Avenue) by the new town. This new community was initially called University Park (the name "Palo Alto" at that time was attached to what is now College Terrace), but was incorporated in 1894 with the name Palo Alto. With the Stanfords' support, Palo Alto grew to the size of Mayfield. Mayfield eventually passed an ordinance banning saloons that took effect in January 1905.[citation needed]

Later history

[edit]On July 2, 1925, Palo Alto voters approved the annexation of Mayfield and the two communities were officially consolidated on July 6, 1925.[20] As a result, Palo Alto has two downtown areas: one along University Avenue and one along California Avenue (renamed after the annexation since Palo Alto already had a Lincoln Avenue).

The Mayfield News wrote its own obituary four days later:

It is with a feeling of deep regret that we see on our streets today those who would sell, or give, our beautiful little city to an outside community. We have watched Mayfield grow from a small hamlet, when Palo Alto was nothing more than a hayfield, to her present size ... and it is with a feeling of sorrow that we contemplate the fact that there are those who would sell or give the city away.[25]

Palo Alto continued to annex more land, including the Stanford Shopping Center area in 1953. Stanford Research Park, Embarcadero Road northeast of Bayshore, and the West Bayshore/San Antonio Road area were also annexed during the 1950s. Large amounts of land west of Foothill Expressway were annexed between 1959 and 1968; this is mostly undeveloped and includes Foothills Park and Arastradero Preserve. The last major annexations were of Barron Park in 1975 and, in 1979, a large area of marshlands bordering the bay.[26]

Many of Stanford University's first faculty members settled in the Professorville neighborhood of Palo Alto. Professorville, now a registered national historic district, is bounded by Kingsley, Lincoln, and Addison Avenues and the cross streets of Ramona, Bryant, and Waverley. The district includes a large number of well-preserved residences dating from the 1890s, including 833 Kingsley, 345 Lincoln, and 450 Kingsley. 1044 Bryant was the home of Russell Varian, co-inventor of the Klystron tube. The Federal Telegraph laboratory site, situated at 218 Channing, is a California Historical Landmark recognizing Lee de Forest's 1911 invention of the vacuum tube and electronic oscillator at that location. While not open to the public, the garage that housed the launch of Hewlett Packard is located at 367 Addison Avenue. Hewlett Packard recently restored the house and garage. A second historic district on Ramona Street can be found downtown between University and Hamilton Avenues. The Palo Alto Chinese School is the oldest in the entire Bay Area. It is also home to the second oldest opera company in California, the West Bay Opera.

One early major business was when Thomas Foon Chew, owner of the Bayside Canning Company in Alviso founded by his father,[27] expanded his business by starting a cannery in 1918 in what was then Mayfield that initially employed 350 workers but later expanded.[28][29] In the 1920s the Bayside Canning Company became one of the largest in the world. In 1949 the Palo Alto cannery, now part of the Sutter Packing Company under the ownership of Safeway, closed; at the time it was the largest employer in Palo Alto with about a 1,000 workers.[28][29] Various businesses used the building since including Fry's Electronics.[28][29]

Palo Alto is also home to a long-standing baseball tradition. The Palo Alto Oaks are a collegiate summer baseball club that has been in the Bay Area since 1950, eight years longer than the San Francisco Giants. The Oaks were originally managed by Tony Makjavich for 49 years.[30] The Oaks were going to fold before the summer 2016 season but were taken on by Daniel Palladino and Whaylan Price, Bay Area baseball coaches who did not want to see the team die. The Oaks have a rich history within the Palo Alto community.[31]

Geography

[edit]

Palo Alto lies in the southeastern section of the San Francisco Peninsula.

It consists of two large parcels of land connected by a narrow corridor. The southern inland section, located south of Interstate 280, is hilly, rural, and lightly populated and is the site of Pearson–Arastradero Preserve and Foothills Park both part of the Palo Alto park system and also large parts of the Los Trancos and Monte Bello Open Space Preserves part of the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District. The city extends as far as Skyline Boulevard along the ridge of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

The northern more densely populated parcel is bordered by San Francisquito Creek (with Menlo Park and East Palo Alto in adjacent San Mateo County beyond) to the north, San Francisco Bay to the north-east, Mountain View, Los Altos, and Los Altos Hills to the east and south-east and Stanford University to the south-west and west. Several major transit routes cross this parcel from the north-west to the south-east. The biggest and closest to the bay is the Bayshore Freeway and going inland are Alma Street/Central Expressway, El Camino Real, and Foothill Expressway. Interstate 280 is parallel and crosses the narrow corridor of land that connects the two parcels that makeup Palo Alto. Somewhat perpendicular to these roads are Sand Hill Road from El Camino until it crosses San Francisquito Creek into Menlo Park, Embarcadero Road, Oregon Expressway/Page Mill Road, Arastradero Road/East Charleston Road, and San Antonio Road (the last forms part of the boundary with Mountain View).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 25.8 square miles (67 km2), of which 23.9 square miles (62 km2) is land and 1.9 square miles (4.9 km2), comprising 7.38%, is water.

The official elevation is 30 feet (9 m) above sea level,[32] but the city boundaries reach well into the northern section of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Water

[edit]Palo Alto is crossed by several creeks that flow north in the direction of the San Francisco Bay, Adobe Creek near its eastern boundary, San Francisquito Creek on its western boundary, and Matadero Creek in between the other two. Arastradero Creek is a tributary to Matadero Creek, and Barron Creek is now diverted to Adobe Creek just south of Highway 101 by a diversion channel. The San Francisquito Creek mainstem is formed by the confluence of Corte Madera Creek and Bear Creek not far below Searsville Dam. Further downstream, Los Trancos Creek is a tributary to San Francisquito Creek below Interstate 280.

Environmental features

[edit]Palo Alto has a number of significant natural habitats, including estuarine, riparian, and oak forest. Many of these habitats are visible in Foothills Park, which is owned by the city. The Charleston Slough contains a rich marsh and littoral zone, providing feeding areas for a variety of shorebirds and other estuarine wildlife.[33]

Climate

[edit]Typical of the South Peninsula region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Palo Alto has a Mediterranean climate with mild, moderately wet winters and warm, dry summers. Typically, in the warmer months, as the sun goes down, the fog bank flows over the foothills to the west and covers the night sky, thus creating a blanket that helps trap the summer warmth absorbed during the day.[citation needed] Even so, it is rare for the overnight low temperature to exceed 60 °F (16 °C).[citation needed]

In January, average daily temperatures range from a low of 39.0 °F (3.9 °C) to a high of 57.8 °F (14.3 °C). In July, average temperatures range from 55.7 to 79.4 °F (13.2 to 26.3 °C). The record high temperature was 108 °F (42 °C) on September 6, 2022, and the record low temperature was 20 °F (−7 °C) on January 11, 1949, and December 24, 1990. Temperatures reach 90 °F (32 °C) or higher on an average of 12.0 days. Temperatures drop to 32 °F (0 °C) or lower on an average of 14.0 days.

Due to the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west, there is a "rain shadow" in Palo Alto, resulting in an average annual rainfall of only 15.12 inches (384 mm). Measurable rainfall occurs on an average of 55.8 days annually. The wettest year on record was 1983 with 32.51 inches (826 mm) and the driest year was 2013 with 3.81 inches (97 mm). The most rainfall in one month was 12.43 inches (316 mm) in February 1998 and the most rainfall in one day was 3.75 inches (95 mm) on February 3, 1998. Measurable snowfall is very rare in the populated areas of Palo Alto, but 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) fell on January 21, 1962.[34] A dusting of snow occasionally occurs in the highest (unpopulated) section of Palo Alto near Skyline Ridge, where the elevation reaches up to 2,812 feet (857 m).[35]

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Palo Alto has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb).[36]

| Climate data for Palo Alto, California, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1922–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

84 (29) |

85 (29) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

108 (42) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

75 (24) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 66.2 (19.0) |

70.9 (21.6) |

75.9 (24.4) |

84.2 (29.0) |

88.6 (31.4) |

93.6 (34.2) |

93.3 (34.1) |

92.4 (33.6) |

91.5 (33.1) |

86.9 (30.5) |

74.4 (23.6) |

65.8 (18.8) |

97.9 (36.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.8 (14.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

65.5 (18.6) |

69.6 (20.9) |

73.3 (22.9) |

78.5 (25.8) |

79.4 (26.3) |

78.7 (25.9) |

79.6 (26.4) |

74.0 (23.3) |

63.7 (17.6) |

57.6 (14.2) |

69.9 (21.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 48.4 (9.1) |

51.0 (10.6) |

54.6 (12.6) |

57.4 (14.1) |

61.4 (16.3) |

65.6 (18.7) |

67.6 (19.8) |

67.0 (19.4) |

66.3 (19.1) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.1 (11.7) |

48.1 (8.9) |

58.5 (14.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 39.0 (3.9) |

41.3 (5.2) |

43.6 (6.4) |

45.3 (7.4) |

49.5 (9.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

55.7 (13.2) |

55.3 (12.9) |

53.0 (11.7) |

48.4 (9.1) |

42.5 (5.8) |

38.6 (3.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 30.6 (−0.8) |

32.5 (0.3) |

35.1 (1.7) |

38.0 (3.3) |

41.6 (5.3) |

46.1 (7.8) |

48.6 (9.2) |

49.7 (9.8) |

46.1 (7.8) |

40.4 (4.7) |

33.5 (0.8) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

22 (−6) |

31 (−1) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

40 (4) |

44 (7) |

37 (3) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.95 (75) |

3.18 (81) |

2.19 (56) |

0.97 (25) |

0.44 (11) |

0.10 (2.5) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.64 (16) |

1.60 (41) |

2.95 (75) |

15.12 (385.06) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.0 | 10.1 | 8.2 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 6.2 | 9.7 | 55.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[37] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2 (mean maxima/minima 1981–2010)[38] | |||||||||||||

Local government

[edit]

Palo Alto was incorporated in 1894. In 1909 a municipal charter created a local government consisting of a fifteen-member city council, with responsibilities for various governmental functions delegated to appointed committees. In 1950, the city adopted a Council–manager government. Several appointed committees continue to advise the city council on specialized issues, such as land-use planning, utilities, and libraries, but these committees no longer have direct authority over City staff. Currently, the city council has seven members.

The mayor and vice-mayor serve one year at a time, with terms ending in January. General municipal elections are held in November of even-numbered years. Council terms are four years long.[39]

According to one study in 2015, the city's effective property tax rate of 0.42% was the lowest of the California cities included in the study.[40]

Politics

[edit]In the California State Legislature, Palo Alto is in the 13th Senate District, represented by Democrat Josh Becker,[41] and in the 23rd Assembly District, represented by Democrat Marc Berman.[42][43]

In the United States House of Representatives, Palo Alto is in California's 16th congressional district, represented by Democrat Anna Eshoo.[44]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Palo Alto has 40,040 registered voters. Of those, 20,857 (52.1%) are registered Democrats, 4,689 (11.7%) are registered Republicans, and 13,520 (33.8%) have declined to state a political party.[45]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 1,658 | — | |

| 1910 | 4,486 | 170.6% | |

| 1920 | 5,900 | 31.5% | |

| 1930 | 13,652 | 131.4% | |

| 1940 | 16,774 | 22.9% | |

| 1950 | 25,475 | 51.9% | |

| 1960 | 52,287 | 105.2% | |

| 1970 | 56,040 | 7.2% | |

| 1980 | 55,225 | −1.5% | |

| 1990 | 55,900 | 1.2% | |

| 2000 | 58,598 | 4.8% | |

| 2010 | 64,403 | 9.9% | |

| 2020 | 68,572 | 6.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[46] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race | Pop 2010 | Pop 2020 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 39,052 | 33,243 | 60.64% | 48.48% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 1,131 | 1,170 | 1.76% | 1.71% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 65 | 37 | 0.10% | 0.05% |

| Asian (NH) | 17,404 | 24,246 | 27.02% | 35.36% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 135 | 146 | 0.21% | 0.21% |

| Some other race (NH) | 254 | 503 | 0.39% | 0.73% |

| Mixed race/multi-racial (NH) | 2,388 | 4,136 | 3.71% | 6.03% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3,974 | 5,091 | 6.17% | 7.42% |

| Total | 64,403 | 68,572 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos can be of any race.

2010

[edit]

The 2010 United States Census reported that Palo Alto had a population of 64,403.[49] The population density was 2,497.5 inhabitants per square mile (964.3/km2). The racial makeup of Palo Alto was 41,359 (64.2%) White, 17,461 (27.1%) Asian, 1,197 (1.9%) African American, 121 (0.2%) Native American, 142 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 1,426 (2.2%) from other races, and 2,697 (4.2%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3,974 persons (6.2%).

The Census reported that 63,820 people (99.1% of the population) lived in households, 205 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 378 (0.6%) were institutionalized.

There were 26,493 households, out of which 8,624 (32.6%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 13,975 (52.7%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,843 (7.0%) had a female householder with no husband present, 659 (2.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 979 (3.7%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 188 (0.7%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 7,982 households (30.1%) were made up of individuals, and 3,285 (12.4%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41. There were 16,477 families (62.2% of all households); the average family size was 3.04.

The population was spread out, with 15,079 people (23.4%) under the age of 18, 3,141 people (4.9%) aged 18 to 24, 17,159 people (26.6%) aged 25 to 44, 18,018 people (28.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 11,006 people (17.1%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.7 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 93.0 males.

There were 28,216 housing units at an average density of 1,094.2 units per square mile (422.5 units/km2), of which 14,766 (55.7%) were owner-occupied, and 11,727 (44.3%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.5%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.6%. 39,176 people (60.8% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 24,644 people (38.3%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

[edit]As of the census of 2000, there were 58,598 people, 25,216 households, and 14,600 families residing in the city.[50] The population density was 955.8/km2 (2,476/sq mi). There were 26,048 housing units at an average density of 424.9/km2 (1,100/sq mi). The racial makeup of the city was 75.76% White, 2.02% Black, 0.21% Native American, 17.22% Asian, 0.14% Pacific Islander, 1.41% from other races, and 3.24% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.65% of the population.

There were 25,216 households, of which 27.2% had resident children under the age of 18, 48.5% were married couples living together, 7.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.1% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.30 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.2% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 32.4% from 25 to 44, 25.9% from 45 to 64, and 15.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.8 males. For every 100 females aged 18 and over, there were 93.6 males.

According to a 2007 estimate, the median income for a household in the city was $119,046, and the median income for a family was $153,197.[51] Males had a median income of $91,051 versus $60,202 for females. The per capita income for the city was $56,257. About 3.2% of families and 4.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.0% of those under age 18 and 5.0% of those age 65 or over.

Housing

[edit]

Palo Alto, north of Oregon Expressway, is filled with older homes, including Craftsman and California Colonials, some of which date back to the 1890s but most of which were built in the first four decades of the 20th century. South of Oregon Expressway, the homes, including many Joseph Eichler-designed or Eichler-style houses, were primarily built in the first 20 years after World War II.

While the city contains homes that now cost anywhere from $800,000 to well over $40 million, much of Palo Alto's housing stock is in the style of California mid-century middle-class suburbia. The median home sale price for all of Palo Alto was $1.2 million in 2007[52] and $1.4 million in July 2009.[53] Palo Alto ranked in as the 5th most expensive city in the United States as of 2007[update], with an average home sales price of $1,677,000.[54] In 2010, Palo Alto ranked as the 2nd most expensive city in the United States, with a four-bedroom, two-bathroom home listing for $1.48 million on average.[55] Palo Alto is by some measures the most expensive college town in the United States.[56]

By 2020, residents' opposition to new housing has resulted in Palo Alto only allowing construction of enough low-income housing to meet 13% of its state-mandated share, and 6% of its share for very-low-income housing.[57]

History of housing

[edit]In the 1920s, racial covenants were used that banned "persons of African, Japanese, Chinese, or Mongolian descent" from purchasing or renting homes in many neighborhoods throughout Palo Alto.[58] In the 1950s, some movements opposed these policies, including the Palo Alto Fair Play Association, as well as architect and developer Joseph Eichler, who built almost 3,000 homes in Palo Alto.[58]

Blockbusting strategies were also employed to instill fear in white neighborhoods and cause White flight out of areas on the outskirts of the city. Blockbusting refers to a practice realtors adopted in which they would advertise the incoming presence of a black family to a neighborhood, causing panic among the white residents who would consequently sell their houses at deflated prices very quickly.[59] One famous blockbusting event is responsible for the prevailing demographic divides between Palo Alto and East Palo Alto.[60]

One of the most destructive policies at the time was redlining. Redlining was a policy put in place by the Federal Housing Association starting in 1937. Through the program, the association could rank neighborhoods from Type A, which was desirable, to Type D (outlined in red) which was deemed hazardous. Residents in Type D neighborhoods were ineligible for loans to buy or fix houses. The program was implemented in a way so that neighborhoods with any kind of African American population were ranked type C or D.[61] This was also the case in Palo Alto and the surrounding areas. Palo Alto's White neighborhoods were ranked mostly Type A and B, allowing for wealth accumulation and eventually resulting in the high housing prices we see today. On the other hand, the surrounding areas were all marked Type C and D, and African Americans found themselves being driven to the outskirts of Palo Alto, what is now mostly East Palo Alto, where there was no money from loans in the economy, leading to a state of decay.[60]

However, for the most part, Palo Alto's housing was built on policies that are still reflected in the current demographics.[60]

Economy

[edit]

Palo Alto serves as a central economic focal point of the Silicon Valley and is home to more than 7,000 businesses employing more than 98,000 people.[62] In the mid-1950s Palo Alto had a railroad village feel and the streets were lined with bungalows and prim storefronts. At a time when only 7 percent of American adults had completed four years of college, more than a third of men living in the Palo Alto suburb had a college degree.[63] In 1949 Wallace Sterling had been appointed as Stanford's president and Frederick Terman became provost. The fledgling Stanford University was reorganized, offering applied educational programs on physics, material science, and electrical engineering. Stanford's basic research capabilities were built up and the laboratory facilities for applied work were brought together in the Stanford Electronics Laboratories.[64]

Many prominent technology firms reside in the Stanford Research Park on Page Mill Road, while nearby Sand Hill Road in the adjacent city of Menlo Park is a notable hub of venture capitalists.

A number of prominent Silicon Valley companies no longer reside primarily in Palo Alto. These include Google (now in Mountain View),[65][66] Facebook (now in Menlo Park),[67] and PayPal (now in San Jose).[65][68]

In 2021, Tesla, Inc. moved its headquarters from Palo Alto to Austin, Texas.[12]

Palo Alto's retail and restaurant trade includes Stanford Shopping Center, an upscale open air shopping center established in 1955, and downtown Palo Alto, centered on University Avenue.[69]

Palo Alto is the location of the first street-level Apple Store,[70] the first Apple mini store,[71] the first West Coast Whole Foods Market store,[72] and the first Victoria's Secret.[73]

Top employers

[edit]

According to the city's 2023 Annual Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[74] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hewlett-Packard | 14,673 |

| 2 | SAP Labs | 14,164 |

| 3 | VMware | 10,720 |

| 4 | Stanford Health Care | 5,500 |

| 5 | Stanford University | 4,060 |

| 6 | Veteran's Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System | 4,400 |

| 7 | Varian Medical Systems | 3,490 |

| 8 | Cooley LLP | 2,324 |

| 9 | Palantir Technologies | 2,026 |

| 10 | Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati | 1,701 |

Utilities

[edit]Palo Alto has a city-run and owned utility, City of Palo Alto Utilities (CPAU), which provides water, electric, gas service, and waste water disposal within city limits,[75] with the minor exception of a rural portion of the city in the hills west of Interstate 280, past the Country Club, which does not receive gas from the city. Almost all other communities in northern California depend on Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) for gas and electricity.

Water and Gas Services (WGS) operates gas and water distribution networks within the city limits. The city operates both gas meters and the distribution pipelines. Water comes from city-operated watershed and wells and the City and County of San Francisco Hetch Hetchy system. The city is located in Santa Clara Valley Water District, North Zone. Hetch Hetchy pipeline #3 and #4 pass through the city.

The city operates its own electric power distribution network and telemetry cable network. Interconnection points tie the city into PG&E's electric transmission system, which brings power from several sources to the city. Palo Alto is a member of a joint powers authority (the Northern California Power Agency), which cooperatively generates electricity for government power providers such as the City of Santa Clara, the City of Redding, and the Port of Oakland. Roughly the same group of entities operate the Transmission Agency of Northern California (TANC). TANC transports power over its own lines from as far as British Columbia through an interconnection with the federal Bonneville Power Administration. A local oddity is a series of joint poles; those primary conductor cross arms are marked PGE and CPA (City of Palo Alto) to identify each utility's side of the shared cross arms.

Palo Alto has an ongoing community debate about the city providing fiber optic connectivity to all residences.[citation needed] A series of pilot programs have been proposed. One proposal called for the city to install dark fiber, which would be made live by a contractor.[citation needed]

Services traditionally attributed to a cable television provider were sold to a regulated commercial concern. Previously the cable system was operated by a cooperative called Palo Alto Cable Coop.[citation needed]

The former Regional Bell Operating Company in Palo Alto was Pacific Telephone, now called AT&T Inc., and previously called SBC and Pacific Bell. One of the earliest central office facilities switching Palo Alto calls is the historic Davenport central office (CO) at 529 Bryant Street.[citation needed] The building was sold and is now the home of the Palo Alto Internet Exchange. The former CO building is marked by a bronze plaque and is located on the north side of Bryant Street between University Avenue and Hamilton Avenue. It was called Davenport after the exchange name at the introduction of dial telephone service in Palo Alto.[citation needed] For example, modern numbers starting with 325- were Davenport 5 in the 1950s and '60s. The Step-by-Step office was scrapped and replaced by stored-program-controlled equipment at a different location about 1980. Stanford calls ran on a Step-by-Step Western Electric 701 PBX until the university purchased its own switch about 1980. It had the older, traditional Bell System 600 Hz+120 Hz dial tone. The old 497-number PBX, MDF, and battery string were housed in a steel building at 333 Bonair Siding. From the 1950s to 1980s, the bulk of Palo Alto calls were switched on Number 5 Crossbar systems. By the mid-1980s, these electromechanical systems had been junked. Under the Bell System's regulated monopoly, local coin telephone calls were ten cents until the early 1980s.[citation needed]

During the drought of the early 1990s, Palo Alto employed water waste patrol officers to enforce water saving regulations.[citation needed] The team, called "Gush Busters", patrolled city streets looking for broken water pipes and poorly managed irrigation systems. Regulations were set to stop restaurants from habitually serving water, runoff from irrigation, and irrigation during the day. The main goal of the team was to educate the public in ways to save water. Citations consisted of Friendly Reminder postcards and more formal notices. To help promote the conservation message, the team only used bicycles and mopeds.[citation needed]

Fire and police departments

[edit]

The city was among the first in Santa Clara County to offer advanced life support (ALS) paramedic-level (EMT-P) ambulance service. In an arrangement predating countywide paramedic service, Palo Alto Fire operates two paramedic ambulances which are theoretically shared with county EMS assets. The Palo Alto Fire Department is currently the only fire department in Santa Clara County that routinely transports patients. Rural Metro holds the Santa Clara County 911 contract and provides transportation in other cities. Enhanced 9-1-1 arrived in about 1980 and included the then-new ability to report emergencies from coin telephones without using a coin. Palo Alto Fire also has a contract with Stanford University to cover most of the campus.[76] In all, the Fire Department has six regular stations plus one opened only during the summer fire season in the foothills.[77]

The police station was originally housed in a stone building at 450 Bryant Street.[78] Still engraved with the words Police Court, the building is now a non-profit senior citizen center, Avenidas.[79] The police are now headquartered in the City Hall high rise. The department has just under 100 sworn officers ranking supplemented by approximately ten reserve officers and professional staff who support the police department and the animal services organization.

Education

[edit]

Public schools

[edit]

The Palo Alto Unified School District provides public education for most of Palo Alto. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, Palo Alto has a student-teacher ratio of 14.9,[80] much lower than some surrounding communities. Juana Briones Elementary has a student/teacher ratio of 14.4.[81] The school board meets at 7 p.m. on the 2nd and 4th Tuesdays of the month; the meetings are open to the public and city, cast live on Channel 28. Channel 28 is operated by the Mid-peninsula Community Media Center[82] in Palo Alto, which is affiliated with the Alliance for Community Media.[83] ACM represents over 2,000 PEG channels in the US. Government-access television (GATV) Cable TV. Palo Alto students attend one of two high schools, Gunn High School or Palo Alto High School. There are also three middle schools, JLS, Greene, and Fletcher.

The Los Altos School District and Mountain View–Los Altos Union High School District provide public education for the Monroe neighborhood portion of Palo Alto off El Camino Real south of Adobe Creek.

Private schools

[edit]

- Athena Academy—a 1st through 8th grade school for dyslexic students founded in 2010.[84]

- Bowman School – a Pre-K to 12 Montessori school founded in 1995[85][86]

- Castilleja School – an all-girls' college preparatory school for grades 6–12 founded in 1907

- Challenger School – a K–8 School[87]

- Esther B. Clark School – a school for children with mental or behavioral challenges[88]

- Fusion Academy Palo Alto – a small for-profit 1-1 alternative school for 6–12[89]

- Gideon Hausner Jewish Day School – a K–8 Jewish day school that opened in 1990; school's name changed from Mid-Peninsula Jewish Community Day School (MPJCDS) to its current name in 2003 to honor Gideon Hausner.[90] Current enrollment is about 300.[91]

- The Girls' Middle School – an independent, all-girls day school founded in 1998 in Mountain View and moved to Palo Alto in 2011. It has about 200 students in grades 6–8.[92][93]

- Kehillah Jewish High School – a high school with both secular and Jewish studies founded in 2002 in San Jose and moved to Palo Alto in 2005.[94]

- Keys School – a co-ed, independent K-8 school[95]

- Living Wisdom School – a K-8 school[96]

- Meira Academy – an Orthodox Jewish all-girls high school, founded in 2011[97]

- Sand Hill School – a K–7 school[98]

- St. Elizabeth Seton Catholic School – a Catholic school for preschool through eighth grade located in Palo Alto[99]

- Silicon Valley International School – a bilingual immersion school with its Palo Alto campus housing the K–5 elementary school. Established in 1979.[100][101]

- Stratford School – a K–8 school[102]

- Tru School – a K–5 school[103]

Weekend schools

[edit]- Palo Alto Chinese School – oldest Chinese school in Bay Area.

Higher education

[edit]Palo Alto is home to Palo Alto University, a school focused on psychology.

The main academic campus of Stanford University, a private research university, is adjacent to Palo Alto.[104] The university also includes lands in the Palo Alto city limits.[105]

Libraries

[edit]

The Palo Alto City Library has five branches, with a total of 265,000 items in their collections.[106] The Mitchell Park Library was rebuilt between 2010 and December 2014 to become the largest in Palo Alto. The former Main Library was then renamed the Rinconada branch. Palo Alto Children's Library is located close to the former Main Library. There are smaller branches in the Downtown and College Terrace neighborhoods.

Media

[edit]

The Palo Alto Daily Post publishes six days a week. Palo Alto Daily News, a unit of the San Jose Mercury News, publishes five days a week. Palo Alto Weekly is published on Fridays. Palo Alto Times, a daily newspaper, served Palo Alto and neighboring cities beginning in 1894. In 1979, it became the Peninsula Times Tribune. The newspaper ceased publication in 1993.[107]

KDOW, 1220 AM, began broadcasting in 1949 as KIBE. It later became KDFC, simulcasting classical KDFC-FM. As KDOW it broadcasts a business news format. The transmitter is in East Palo Alto near the western approach to the Dumbarton Bridge. Power is 5,000 watts daytime and 145 watts nighttime. KZSU at 90.1 FM is owned by Stanford University. KFJC at 89.7 FM is licensed to nearby Los Altos and is licensed to the Foothill-De Anza Community College District.

KTLN-TV, virtual channel 68, transmits from Mt. Allison across San Francisco bay, east of Palo Alto.

The Midpeninsula Community Media Center provides public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable television channels 26, 28, 29, 30 and 75.[108]

Transportation

[edit]

Roads

[edit]Palo Alto is served by two major freeways, Highway 101 and Interstate 280 and is traversed by the Peninsula's main north–south boulevard, El Camino Real (SR 82). Santa Clara County maintains 2 expressways in Palo Alto; Route G3 is the city's main east–west route and is the only road in the city that connects the two freeways directly. Route G6 travels through the city as Alma Street, serving as an alternate route to SR 82. The city is also served indirectly by State Route 84 which traverses the Dumbarton Bridge to the north, and State Route 85 via Mountain View to the south.

There are no parking meters in Palo Alto, and all municipal parking lots and multi-level parking structures are free but limited to two or three hours per weekday 8am–5pm.[109] Downtown Palo Alto has recently added many new lots to fill the overflow of vehicles.[110] Beginning in 2014, Palo Alto has begun implementing permit parking in some areas of the town.[111]

Air

[edit]Palo Alto is served by Palo Alto Airport (KPAO), one of the busiest single-runway general aviation airports in the country. It is used by many daily commuters who fly (usually in private single-engine aircraft) from their homes in the Central Valley to work in the Palo Alto area.

The nearest commercial airport is San Jose International Airport (SJC) (also known as Norman Mineta Airport), about 15 miles (24 km) southeast. Nearby is San Francisco International Airport (SFO), about 21 miles (34 km) north.

Rail

[edit]

Passenger train service is provided exclusively by Caltrain, with service between San Francisco and San Jose, extending to Gilroy. Caltrain has two regular stations in Palo Alto, the main one at the Palo Alto Station in downtown Palo Alto (local, limited, and express). The main Palo Alto station is the second busiest (behind 4th and King in San Francisco) on the entire Caltrain line. The other station is located at California Avenue, (local and limited).[112] A third, the Stanford station, located beside Alma Street at Embarcadero Road, is used for occasional sports events (generally football) at Stanford Stadium. Freight trains through Palo Alto are operated by Union Pacific (formerly Southern Pacific).

There are 4 grade crossings within city limits, at the intersections of Alma St, Churchill Ave, Meadow Dr, and Charleston Rd. The city has made plans upgrade the southern crossings and even proposed closing the Churchill Ave crossing completely to road traffic, but the project has been a hot-button issue for local residents and politicians for over a decade. The current proposed solution is elevating the tracks above grade, while lowering the roadway below grade.[113] A subway tunnel underneath the right of way and converting the old track bed into a park was also proposed, but eventually dropped after it was deemed to be too costly and concerns over environmental impacts.[114] Despite increased train service and Caltrain already installing Electric Service equipment on the mainline, Palo Alto has no green-lighted plans to address the crossings, except for immediate changes at Churchill Ave to address safety concerns at that intersection.[115]

Bus

[edit]The Palo Alto Transit Center adjacent to the Palo Alto Train Station is the major bus hub for northern Santa Clara county. The Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) provides primary bus service through Palo Alto with service to the South Bay and Silicon Valley. San Mateo County Transit District (SamTrans) provides service to San Mateo County to the north but some lines include the Palo Alto Transit Center. The Stanford University Free Shuttle (Marguerite) provides a supplementary bus service between Stanford University and the Palo Alto Transit Center, and the Palo Alto Free Shuttle (Crosstown and Embarcadero), which circulates frequently, and provides service to major points in Palo Alto, including the main library, downtown, the Municipal Golf Course, the Palo Alto Transit Center, and both high schools.[116] The Dumbarton Express is a weekday-only limited stop bus service that connects Union City BART in the East Bay to Palo Alto via the Dumbarton Bridge serving Stanford University, Stanford Research Park, Palo Alto Transit Center, and Veterans Hospital.

Cycling

[edit]

Cycling is a popular mode of transportation in Palo Alto. 9.5% of residents bicycle to work,[117] the highest percentage of any city in the Bay Area, and third highest in the United States, after Davis, California and Boulder, Colorado. Since 2003, Palo Alto has received a Bicycle Friendly Community status of "Gold" from the League of American Bicyclists.

The city's flat terrain and many quiet tree-shaded residential streets offer comfort and safety to cyclists, and the temperate climate makes year-round cycling convenient. Palo Alto pioneered the bicycle boulevard concept in the early 1980s, enhancing residential Bryant Street to prioritize it for cyclists by removing stop signs, providing special traffic signals, and installing traffic diverters, and a bicycle/pedestrian bridge over Matadero Creek.[citation needed] However, busy arterial streets which often offer the fastest and most direct route to many destinations, are dangerous for cyclists due to high volumes of fast-moving traffic and the lack of bicycle lanes.[citation needed] El Camino Real, Alma Street, and Embarcadero and Middlefield roads, all identified as "high priorities" for adding bicycle lanes to improve safety by the 2003 Palo Alto Bicycle Transportation Plan, still contain no provisions for cyclists.

The Palo Alto Police Department decided to stop using tasers to detain bicyclists after a 2012 incident in which a 16-year-old boy, who had bicycled through a stop sign, was injured after police officers pursued him, fired a taser at him and suddenly braked their patrol car in front of him, causing the boy to crash.[118]

Walking

[edit]Conditions for walking are excellent in Palo Alto except for crossing high-volume arterial streets such as El Camino Real and Oregon Expressway. Sidewalks are available on nearly every city street, with the notable exception of the Barron Park neighborhood, which was the last to be incorporated into the city. Palo Alto's Street grid is well-connected with few dead-end streets, especially in the city's older northern neighborhoods. An extensive urban forest, which is protected by the city's municipal code, provides shade and visual diversity, and slows motor vehicle traffic. 4.8% of residents walk to work.[117]

Sister cities

[edit]Palo Alto has seven sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Heidelberg, Germany, since 2017 [120]

Heidelberg, Germany, since 2017 [120]

In 1989, Palo Alto received a gift of a large, whimsical wooden sculpture called Foreign Friends (Fjärran Vänner)—of a man, woman, dog and bird sitting on a park bench—from Linköping. The sculpture was praised by some, called "grotesque" by others, and became a lightning rod for vandals. It was covered with a large, addressed postcard marked "Return to Sender." A former Stanford University professor was arrested for attempting to light it on fire. It was also doused with paint.[121] When the original heads were decapitated on Halloween, 1993, the statue became a shrine—flowers bouquets and cards were placed upon it. Following an anonymous donation, the heads were restored. Within weeks, the restored heads were decapitated again, this time disappearing. The heads were eventually replaced with new ones, which generated even more distaste, as many deemed the new heads even less attractive.[121]

A few months later, the man's arm was chopped off, the woman's lap was vandalized, the bird was stolen, and the replacements heads were decapitated and stolen.[121] The sculpture was removed from its location on Embarcadero Road and Waverley Avenue in 1995, dismantled, and placed in storage until it was destroyed in 2000. Ironically, the statue was designed not as a lasting work of art, but as something to be climbed on with a lifespan of 10 to 25 years.[122]

Notable buildings and other points of interest

[edit]Historical buildings and architecture

[edit]

- Frenchman's Tower was built in 1876[123]

- Former Palo Alto Community House, at the intersection of University Avenue and El Camino Real; designed by Julia Morgan as the YWCA Hostess House but first used as a social centre in Camp Fremont during World War I; now a restaurant, MacArthur Park.

- Lou Henry Hoover Girl Scout House, "the oldest scout meeting house remaining in continuous use in the United States".[124]

- Packard's garage where the company Hewlett-Packard was started in 1939.

- Printers Inc. Bookstore, now defunct, was a landmark independent bookstore on California Ave. and was referenced in Vikram Seth's novel, The Golden Gate. It closed in 2001.

- Ramona Street Architectural District one block of downtown office buildings and restaurants designed and built by Pedro Joseph de Lemos

- Saint Thomas Aquinas Church is the oldest church in Palo Alto.

- Woman's Club of Palo Alto was built in 1916 in a Tudor-Craftsman style, listed in 2014 in the National Register of Historic Places.

Nature and hiking

[edit]

- Arastradero Preserve

- Elizabeth F. Gamble Garden, public botanical garden[125]

- Esther Clark Park, a small open oak/grassland park connecting to Los Altos Hills

- Foothills Nature Preserve

- Palo Alto Baylands Nature Preserve

Museums, art, and entertainment

[edit]

- Palo Alto Art Center

- Pacific Art League

- Stanford Shopping Center

- University Avenue (Downtown Palo Alto)

- Palo Alto Children's Theatre

- Palo Alto Players

- Stanford Theatre

- Palo Alto Junior Museum and Zoo

- The Foster Museum

- Winter Lodge Ice Skating Rink

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of cities and towns in California

- List of cities and towns in the San Francisco Bay Area

- List of people from Palo Alto

- Mayfield Brewery

References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council & Mayor". City of Palo Alto. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Palo Alto". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Palo Alto (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 26, 2021.

- ^ Scheinin, Richard (March 29, 2016). "Palo Alto, Atherton crack top 10 priciest ZIP codes in U.S." San Jose Mercury News.

- ^ White, Martha C. (January 5, 2015). "America's Most Outrageously Expensive Places to Live". Time.

- ^ "CDC releases preliminary findings on Palo Alto suicide clusters". The Stanford Daily. July 21, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Apple – 1 operation manual, 1976" (PDF). S3data.computerhistory.org. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Green, Jason (July 17, 2013). "Google Buys Nearly 15 acres in Palo Alto". San Jose Mercury-News. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ "Logitech History" (PDF). Logitech.com. March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Lora Kolodny (October 7, 2021). "Tesla moves headquarters from California to Texas". CNBC. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Ford Opens New Silicon Valley Research Center to Drive Innovation in Connectivity, Mobility, Autonomous Vehicles | Ford Media Center". media.ford.com. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ "Advanced Technology Center". Lockheed Martin. August 4, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rolle, Andrew (1987). California: A History (4th ed.). Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson. p. 52. ISBN 0-88295-839-9. OCLC 13333829.

- ^ "Early History". National Park Service. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ "Plat of the Rancho Rincon de San Francisquito, finally confirmed to Teodoro and Secundino Robles : [Santa Clara Co., Calif.] / as located by the U.S. Surveyor General". Cdlib.org. August 23, 1863.

- ^ "Spanishtown Site". Nps.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Graham, Doug (Summer 2003). "Barron Park History". Barron Park Association Newsletter. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ward Winslow, ed. (1993). "Neighboring Mayfield". Palo Alto: A Centennial History. Palo Alto, California: Palo Alto Historical Association. pp. 23–43. ISBN 9780963809834.

- ^ "The San Jose Railroad". Daily Alta California. October 18, 1863. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ "Early Milestones". Caltrain.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Holloway, Christy (Spring–Summer 2011). "A Brief Human and Natural History of Stanford's Dish Open Space". Sandstone and Tile: 15–20. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ "Palo Alto Comprehensive Plan, page L-3". Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- ^ Diamond, Diana (January 6, 2015). "Laying it on thick during change of the guard in Palo Alto". Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Land Use and Community Design". Palo Alto Comprehensive Plan. p. 50. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- ^ "Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California (Chinese Americans)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Sheyner, Gennady (July 31, 2019). "History of Fry's site complicates city's redevelopment plans". www.paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Staff Report (ID # 10499): HRE Cannery (PDF). Palo Alto Historic Resources Board. July 25, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Palo Alto Oaks headed to the World Series". Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Sports, John Reid/Palo Alto Online. "The Palo Alto Oaks gain new baseball life for a second time". Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "GNIS Detail – Palo Alto". geonames.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Jenks, 1976

- ^ "Central California". Dri.edu.

- ^ "Snow-capped Palo Alto". Palo Alto Online. December 15, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Palo Alto, California Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.com.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Palo Alto, CA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ "City Council & Mayor". City of Palo Alto. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Landes, Emily (December 3, 2016). "S.F. lost almost $450 million in revenue last year thanks to Prop. 13". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "Senators". State of California.

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ "Members: Assembly Internet". State of California.

- ^ "California's 16th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015. Until 1980 Palo Alto grew in part by annexing neighboring communities

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Palo Alto, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "P2 HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Palo Alto, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Palo Alto city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Palo Alto city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 23, 2024.

- ^ "S1903: Median Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2007 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars) 2005–2007 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Configurable Real Estate Data Reports – CoreLogic". Corelogic.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Configurable Real Estate Data Reports – CoreLogic". Corelogic.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2010.

- ^ "2007 Coldwell Banker Home Price Comparison Index Reveals That $2.1 Million Separates Beverly Hills from Killeen, Texas" (Press release). Coldwell Banker. September 26, 2007. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2022 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Top 10 most expensive real estate markets in the US". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 27, 2011.

- ^ "Coldwell Banker Ranks Major College Football Town's Home Affordability" (Press release). Coldwell Banker. November 18, 2008. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2022 – via Business Wire.

- ^ Hansen, Louis (June 23, 2020). "Fierce, 7-year NIMBY battle in Palo Alto reaches a conclusion – Big $5 million homes rise on site once eyed for affordable senior units". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

Silicon Valley cities have widely and prodigiously failed to meet state goals for affordable housing. Palo Alto is near the bottom of the pack, providing just 6 percent of its target for very low income housing, and 13 percent of its low income housing in the most recent development period. New state guidelines will impose stiffer penalties for ignoring the standards. But the community resistance to new housing common in Palo Alto and many other Bay Area cities has a stubborn and lasting affect.

- ^ a b Kenrick, Chris (July 3, 2020). "Not all neighborhoods were created equal in Palo Alto – A look at how real estate policies undermined Black homeownership". Palo Alto Online.

- ^ Gaspaire, Brent (January 7, 2013). "Blockbusting". Blackpast.org.

- ^ a b c Montojo, Nicole; Moore, Eli; Mauri, Nicole (October 2, 2019). "Roots, Race & Place: A History of Racially Exclusionary Housing in the San Francisco Bay Area". Othering and Belonging Institute. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ "Palo Alto History". Paloaltohistory.org.

- ^ "Palo Alto Business Facts". Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Margaret O'Mara (2019). The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 9780399562198.

- ^ Margaret O'Mara (2019). The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 30. ISBN 9780399562198.

- ^ a b Peter Day (August 27, 2010). "165 University Avenue: Silicon Valley's 'lucky building'". BBC News. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Julie Bort (October 6, 2013). "Tour Google's Luxurious 'Googleplex' Campus In California". Business Insider Inc. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Emil Protalinski (December 19, 2011). "Facebook completes move from Palo Alto to Menlo Park". ZDNet. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Jordan Novet (February 11, 2014). "PayPal chief reams employees: Use our app or quit". VentureBeat. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ Slice of cheese pizza at Tresidder Union: $2.75 Econ 1 textbook: $123.56 Undergraduate tuition: $29,847 Bloomingdale's across the street Priceless Archived February 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine By Jesse Oxfeld, (July/August 2004) Feature Story, STANFORD Magazine, accessed August 18, 2006

- ^ Apple Stores – 2001–2003 Archived June 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine – accessed November 30, 2010

- ^ Press Info – Apple Unveils New "Mini" Retail Store Design Archived March 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Apple (October 14, 2004). Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Whole Foods Market History". Wholefoodsmarket.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ 5 Things You Didn't Know: Victoria's Secret. AskMen. Retrieved on July 21, 2013

- ^ "City of Palo Alto FY 2023 CAFR" (PDF). Cityofpaloalto.org. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ "Utilities – City of Palo Alto". Cityofpaloalto.org.

- ^ Frazier, Greg (October 19, 2017). "Palo Alto cuts 11 firefighter jobs after Stanford reduces contract". The Mercury News. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "City of Palo Alto, CA – Fire Stations". Cityofpaloalto.org. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ George, Carolyn. "440 – 450 Bryant Street". Pastheritage.org. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "The History of our Programs & Services | Avenidas". Avenidas. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "District Detail for Palo Alto Unified". National Center for Educational Statistics. Retrieved April 18, 2010.

- ^ "Search for Public Schools – School Detail for Juana Briones Elementary". Ed.gov.

- ^ "MidPen Media Center – Lights, Cameras, Community Action". Midpenmedia.org.

- ^ "No content available". alliancecm.org.

- ^ "Our Story". Athena Academy. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Jacqueline (May 11, 2017). "Palo Alto: Bowman school plans large expansion". The Mercury News. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "About – Bowman School". Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Palo Alto, CA Private School | Preschool – 8th Grade". Challenger School. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "Esther B. Clark School". Children's Health Council. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- ^ Kadvany, Elena (July 3, 2015). "Where Palo Alto students learn in a class of one". Paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- ^ "Our History - Gideon Hausner Jewish Day School". www.hausnerschool.org. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "Hausner at a Glance - Gideon Hausner Jewish Day School". www.hausnerschool.org. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "The Girls' Middle School – Igniting the spark of knowledge & self-discovery". Girlsms.org.

- ^ "Mission, History, & Future – The Girls' Middle School". Girlsms.org. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Kehillah High sees big growth". Jweekly.com. May 6, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Our Mission". Keys School. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- ^ "Living Wisdom School". Livingwisdomschool.org/.

- ^ "Meira Academy". Meiraacademy.org.

- ^ "Sand Hill School". Chconline.org.

- ^ "About Us". setonpaloalto.org. St. Elizabeth Seton Catholic School. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- ^ "From Peninsula French American School to INTL | Palo Alto, Menlo Park". www.siliconvalleyinternational.org. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "Elementary School at INTL | Private School in Palo Alto, CA". www.siliconvalleyinternational.org. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "Bay Area Independent School, Best Schools in California, K-8 School". Stratfordschools.com.

- ^ "Tru – a private school in Palo Alto". truschool.org.

- ^ "Palo Alto General Plan Update: Land Use Element" (PDF). City of Palo Alto. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "2020 census - census block map: Palo Alto city, CA" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 3 (PDF p. 4/7). Retrieved July 1, 2023.

Stanford Univ

- ^ "Library". Cityofpaloalto.org. Archived from the original on August 7, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2009.

- ^ "The Media Business: Paper Closes In California". The New York Times. March 15, 1993. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ "MidPen Media Center – Lights, Cameras, Community Action". Communitymediacenter.net.

- ^ "City of Palo Alto, CA – Parking". Cityofpaloalto.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Sheyner, Gennady (October 12, 2017). "Commission pans parking meter plan". Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Sheyner, Gennady (December 3, 2014). "Palo Alto launches downtown parking-permit program". www.paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Caltrain This station was the primary station for Mayfield before it was annexed. Timetable". Caltrain.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014.

- ^ Sheyner, Gennady (November 24, 2023). "Caltrain plans for 4-track segments complicate Palo Alto's effort to redesign rail crossings". Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

- ^ Report of the Expanded Community Advisory Panel (XCAP) on Grade Separations for Palo Alto (PDF) (Report). Connecting Palo Alto. March 4, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "Alma Street/Churchill Avenue Safety Improvements Project". City of Palo Alto Office of Transportation. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "Free Shuttle Schedule". Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b "American Community Survey 2010 – 2012, Table S0801, Commuting Characteristics By Sex", U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Green, Jason (January 9, 2014). "Palo Alto: Police no longer using Tasers to stop fleeing cyclists". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- ^ "Sister City Organization of Palo Alto". City of Palo Alto. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ "Heidelberg Adopted as Palo Alto's Newest Sister City". City of Palo Alto. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Foreign Friends: An Unfriendly Welcome". Palo Alto History.

- ^ "Everyone's a critic". Palo Alto Online. June 29, 2005.

- ^ Cady, Theron G. (1948), The Legend of Frenchmen's Tower, Peninsula Life Magazine: C-T Publishers, San Carlos, California, archived from the original on May 24, 2017, retrieved August 10, 2011

- ^ "Palo Alto Girl Scouts". Girlscoutsofpaloalto.org.

- ^ Reckers, Ed. "Elizabeth F. Gamble Garden". Gamblegarden.org.

Further reading

[edit]- A description of high-tech life in Palo Alto around 1995 is found in the novel by Douglas Coupland, Microserfs.

- Tarnoff, Ben, "Better, Faster, Stronger" (review of John Tinnell, The Philosopher of Palo Alto: Mark Weisner, Xerox PARC, and the Original Internet of Things, University of Chicago Press, 347 pp.; and Malcolm Harris, Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World, Little, Brown, 708 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 14 (September 21, 2023), pp. 38–40. "[Palo Alto is] a place where the [United States'] contradictions are sharpened to their finest points, above all the defining and enduring contradictions between democratic principle and antidemocratic practice. There is nothing as American as celebrating equality while subverting it. Or as Californian." (p. 40.)

- Bowling, Matt, and Betty Gerard. Palo Alto Remembered: Stories from a City’s Past. Palo Alto, California: Palo Alto Historical Association, 2012.

- Harris, Malcolm. Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World. First edition. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2023.