Mary of Bethany

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

Mary of Bethany | |

|---|---|

Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, Johannes Vermeer, before 1654–1655, oil on canvas (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh) – Mary is seated at the feet of Jesus | |

| Disciple of Jesus; Righteous Mary; Sister of Lazarus and Martha; The Anointer; Myrrhbearer | |

| Born | Bethany, Judaea, Roman Empire [1] |

| Died | 1st Century AD |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Orthodoxy Oriental Orthodoxy Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Major shrine | The Holy Monastery of Martha and Mary in Al-Eizariya (Bethany), Palestine[2] |

| Feast | June 4 (Eastern), July 29 (Western) |

| Attributes | Woman holding an alabaster jar of myrrh perfume and holding her hair |

| Patronage | Patroness of Spiritual Studies, Lectors and Commentators in the Philippines [3] |

Mary of Bethany[a] is a biblical figure mentioned by name in the Gospel of John and probably the Gospel of Luke in the Christian New Testament. Together with her siblings Lazarus and Martha, she is described as living in the village of Bethany, a small village in Judaea to the south of the Mount of Olives near Jerusalem.[4]

Western Christianity initially identified Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene and the sinful woman of Luke 7 (Luke 7:36–50). This influenced the Roman Rite liturgy of the feast of Mary Magdalene, with a Gospel reading about the sinful woman and a collect referring to Mary of Bethany. After the liturgical revision in 1969 and 2021, the feast of Mary Magdalene continues to be on 22 July, while Mary of Bethany is celebrated as a separate saint, along with her siblings Lazarus and Martha on 29 July. [5][6] In Eastern Christianity and some Protestant traditions, Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene are also considered separate persons.[7] The Eastern Orthodox Church has its own traditions regarding Mary of Bethany's life beyond the gospel accounts.

Biblical references

[edit]Gospel of John

[edit]

In the Gospel of John, a Mary appears in connection to two incidents: the raising from the dead of her brother Lazarus[8] and the anointing of Jesus.[9] The identification of this being the same Mary in both incidents is given explicitly by the author: "Now a man named Lazarus was sick. He was from Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. This Mary, whose brother Lazarus now lay sick, was the same one who poured perfume on the Lord and wiped his feet with her hair."[10] The mention of her sister Martha suggests a connection with the woman named Mary in Luke 10:38-42.

In the account of the raising of Lazarus, Jesus meets with the sisters in turn: Martha followed by Mary. Martha goes immediately to meet Jesus as he arrives, while Mary waits until she is called. As one commentator notes, "Martha, the more aggressive sister, went to meet Jesus, while quiet and contemplative Mary stayed home. This portrayal of the sisters agrees with that found in Luke 10:38–42."[11] When Mary meets Jesus, she falls at his feet. In speaking with Jesus, both sisters lament that he did not arrive in time to prevent their brother's death: "Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died."[12] But where Jesus' response to Martha is one of teaching, calling her to hope and faith, his response to Mary is more emotional: "When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who had come along with her also weeping, he was deeply moved in spirit and troubled.[13] As the 17th century Welsh commentator Matthew Henry notes, "Mary added no more, as Martha did; but it appears, by what follows, that what she fell short in words she made up in tears; she said less than Martha, but wept more."[14]

Anointing of Jesus

[edit]A narrative in which Mary of Bethany plays a central role is the anointing of Jesus, an event reported in the Gospel of John in which a woman pours the entire contents of an alabastron of very expensive perfume over the feet[15] of Jesus. Only in this account[16] is the woman identified as Mary, with the earlier reference in John 11:1–2 establishing her as the sister of Martha and Lazarus.

Six days before the Passover, Jesus arrived at Bethany, where Lazarus lived, whom Jesus had raised from the dead. Here a dinner was given in Jesus' honor. Martha served, while Lazarus was among those reclining at the table with him. Then Mary took about a pint of pure nard, an expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesus' feet and wiped his feet with her hair. And the house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume.

But one of his disciples, Judas Iscariot, who was later to betray him, objected, "Why wasn't this perfume sold and the money given to the poor? It was worth a year's wages." He did not say this because he cared about the poor but because he was a thief; as keeper of the money bag, he used to help himself to what was put into it.

"Leave her alone", Jesus replied. "It was intended that she should save this perfume for the day of my burial. You will always have the poor among you, but you will not always have me."

The woman's name is not given in the Gospels of Matthew[17] and Mark,[18] but the event is likewise placed in Bethany, specifically at the home of one Simon the Leper, a man whose significance is not explained elsewhere in the gospels.

According to the Markan account, the perfume was the purest of spikenard. Some of the onlookers were angered because this expensive perfume could have been sold for a year's wages, which Mark enumerates as 300 denarii, and the money given to the poor. The Gospel of Matthew states that the "disciples were indignant" and John's gospel states that it was Judas Iscariot who was most offended (which is explained by the narrator as being because Judas was a thief and desired the money for himself). In the accounts, Jesus justifies Mary's action by stating that they would always have the poor among them and would be able to help them whenever they desired, but that he would not always be with them and says that her anointing was done to prepare him for his burial. As one commentator notes, "Mary seems to have been the only one who was sensitive to the impending death of Jesus and who was willing to give a material expression of her esteem for him. Jesus' reply shows his appreciation of her act of devotion."[11] The accounts in Matthew and Mark adds these words of Jesus, "I tell you the truth, wherever this gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her".[19]

Easton (1897) noted that it would appear from the circumstances that the family of Lazarus possessed a family vault[20] and that a large number of Jews from Jerusalem came to console them on the death of Lazarus,[21] that this family at Bethany belonged to the wealthier class of the people. This would help explain how Mary of Bethany could afford to possess quantities of expensive perfume.[22]

A similar anointing is described in the Gospel of Luke[23] as occurring at the home of one Simon the Pharisee in which a woman who had been sinful all her life, and who was crying, anointed Jesus' feet and, when her tears started to fall on his feet, she wiped them with her hair. Luke's account (as well as John's) differs from that of Matthew and Mark by relating that the anointing is to the feet rather than the head. Although it is a subject of considerable debate, many scholars hold that these actually describe two separate events.[24]

Jesus' response to the anointing in Luke is completely different from that recorded in the other gospels to the anointing in their accounts. Rather than Jesus' above-mentioned comments on the "poor you will always have with you", in Luke he tells his host the Parable of the Two Debtors. As one commentator notes, "Luke is the only one to record the parable of the two debtors, and he chooses to preserve it in this setting. ...If one considers the other gospel accounts as a variation of the same event, it is likely that the parable is not authentically set. Otherwise, the powerful message from the parable located in this setting would likely be preserved elsewhere, too. However, if one considers the story historically accurate, happening in Jesus' life apart from the similar incidents recorded in the other gospels, the question of the authenticity of the parable receives a different answer. ...John Nolland, following Wilckens' ideas, writes: 'There can hardly be a prior form of the episode not containing the present parable, since this would leave the Pharisee's concerns of v 39 with no adequate response'."[25]

Luke 10

[edit]In chapter 10 of the Gospel of Luke, Jesus visits the home of two sisters named Mary and Martha, living in an unnamed village. Mary is contrasted with her sister Martha, who was "cumbered about many things"[26] while Jesus was their guest, while Mary had chosen "the better part", that of listening to the master's discourse.[22]

As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, He came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord's feet listening to what he said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, "Lord, don't you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!" "Martha, Martha," the Lord answered, "you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her."

For Mary to sit at Jesus' feet, and for him to allow her to do so, was itself controversial. In doing so, as one commentator notes, Mary took "the place of a disciple by sitting at the feet of the teacher. It was unusual for a woman in first-century Judaism to be accepted by a teacher as a disciple."[27]

Most Christian commentators have been ready to assume that the two occurrences of sisters named as Mary and Martha refer the same pair of sisters.

Medieval Western identification with Mary Magdalene

[edit]In medieval Western Christian tradition, Mary of Bethany was identified as Mary Magdalene perhaps in large part because of a homily given by Pope Gregory the Great in which he taught about several women in the New Testament as though they were the same person.[28] This led to a conflation of Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene as well as with another woman (beside Mary of Bethany who anointed Jesus), and the woman caught in adultery. Eastern Christianity never adopted this identification. In his article in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia, Hugh Pope stated, "The Greek Fathers, as a whole, distinguish the three persons: the 'sinner' of Luke 7:36–50; the sister of Martha and Lazarus, Luke 10:38–42 and John 11; and Mary Magdalen."[29]

Father Hugh Pope enumerated the accounts of each of these three persons (the unnamed "sinner", Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Bethany) in the Gospel of Luke and concluded that, based on these accounts, "there is no suggestion of an identification of the three persons, and if we had only Luke to guide us we should certainly have no grounds for so identifying them [as the same person]." He then explains first the position, at that time general among Catholics, equating Mary of Bethany with the sinful woman of Luke by referring to John 11:2, where Mary is identified as the woman who anointed Jesus, and noting that this reference is given before John's account of the anointing in Bethany:

John, however, clearly identifies Mary of Bethany with the woman who anointed Christ's feet (12; cf. Matthew 26 and Mark 14). It is remarkable that already in John 11:2, John has spoken of Mary as "she that anointed the Lord's feet", he aleipsasa. It is commonly said that he refers to the subsequent anointing which he himself describes in 12:3–8; but it may be questioned whether he would have used he aleipsasa if another woman, and she a "sinner" in the city, had done the same. It is conceivable that John, just because he is writing so long after the event and at a time when Mary was dead, wishes to point out to us that she was really the same as the "sinner". In the same way Luke may have veiled her identity precisely because he did not wish to defame one who was yet living; he certainly does something similar in the case of St. Matthew whose identity with Levi the publican (5:27) he conceals. If the foregoing argument holds good, Mary of Bethany and the "sinner" are one and the same.[29]

Hugh Pope then explained the identification of Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalene by the presumption that, because of Jesus' high praise of her deed of anointing him, it would be incredible that she should also not have been at his crucifixion and resurrection. Since Mary Magdalene is reported to have been present on those occasions, by this reasoning, she must therefore be the same person as Mary of Bethany:

An examination of John's Gospel makes it almost impossible to deny the identity of Mary of Bethany with Mary Magdalen. From John we learn the name of the "woman" who anointed Christ's feet previous to the last supper. We may remark here that it seems unnecessary to hold that because Matthew and Mark say "two days before the Passover", while John says "six days" there were, therefore, two distinct anointings following one another. John does not necessarily mean that the supper and the anointing took place six days before, but only that Christ came to Bethany six days before the Passover. At that supper, then, Mary received the glorious encomium, "she hath wrought a good work upon Me. ...In pouring this ointment upon My body she hath done it for My burial. ...Wheresoever this Gospel shall be preached ... that also which she hath done shall be told for a memory of her." Is it credible, in view of all this, that this Mary should have no place at the foot of the cross, nor at the tomb of Christ? Yet it is Mary Magdalen who, according to all the Evangelists, stood at the foot of the cross and assisted at the entombment and was the first recorded witness of the Resurrection. And while John calls her "Mary Magdalen" in 19:25, 20:1, and 20:18, he calls her simply "Mary" in 20:11 and 20:16.[29]

French scholar Victor Saxer dates the identification of Mary Magdalene as a prostitute, and as Mary of Bethany, to a sermon by Pope Gregory the Great on 21 September 591 A.D., where he seemed to combine the actions of three women mentioned in the New Testament and also identified an unnamed woman as Mary Magdalene. In another sermon, Gregory specifically identified Mary Magdalene as the sister of Martha mentioned in Luke 10.[30] But according to a view expressed more recently by theologian Jane Schaberg, Gregory only put the final touch to a legend that already existed before him.[31]

Western Christianity's identification of Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany was reflected in the arrangement of the General Roman Calendar, until this was altered in 1969,[32] reflecting the fact that by then the common interpretation in the Catholic Church was that Mary of Bethany, Mary Magdalene and the sinful woman who anointed the feet of Jesus were three distinct women.[33]

Eastern Orthodox tradition

[edit]In Orthodox Church tradition, Mary of Bethany is honored as a separate individual from Mary Magdalene. Though they are not specifically named as such in the gospels, the Orthodox Church counts Mary and Martha among the Myrrh-bearing Women. These faithful followers of Jesus stood at Golgotha during the Crucifixion of Jesus and later came to his tomb early on the morning following the Sabbath with myrrh (expensive oil), according to the Jewish tradition, to anoint their Lord's body. The Myrrhbearers became the first witnesses to the Resurrection of Jesus, finding the empty tomb and hearing the joyful news from an angel.[34]

Orthodox tradition also relates that Mary's brother Lazarus was cast out of Jerusalem in the persecution against the Jerusalem Church following the martyrdom of St. Stephen. His sisters Mary and Martha fled Judea with him, assisting him in the proclaiming of the Gospel in various lands.[35] According to Cyprian tradition, the three later moved to Cyprus, where Lazarus became the first Bishop of Kition (modern Larnaca).[36]

Later life

[edit]There are several traditions surrounding the later life of Mary of Bethany. One tradition holds that she traveled to Ephesus with the Apostle John and lived there until her death. Another tradition suggests that she went to France with Lazarus and Martha, and may have settled in the town of Tarascon, where she is still venerated as a saint.

Commemoration as a saint

[edit]In the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, Mary of Bethany is celebrated, together with her brother Lazarus, on 29 July, the memorial of their sister Martha.[5] In 2021, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments added their names to the memorial, making it a liturgical celebration of all three family members.[37]

Also in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church, 29 July is the date of the commemoration of Mary (together with Martha and Lazarus), as is the case in the Calendar of saints of the Episcopal Church and the Church of England (together with Martha).[38]

She is commemorated in the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches with her sister Martha on 4 June, as well as on the Sunday of the Myrrhbearers (the Third Sunday of Pascha). She also figures prominently in the commemorations on Lazarus Saturday (the day before Palm Sunday).

Mary is remembered (with Martha and Lazarus) in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 29 July.[39]

Gallery

[edit]-

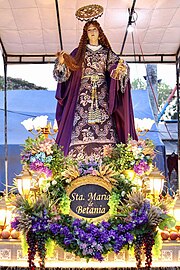

Processional Statue Image of St. Mary of Bethany in Milaor, Camarines Sur

-

Processional Statue Image of St. Mary of Bethany in Dumangas, Iloilo

Notes

[edit]- ^ Judeo-Aramaic: מרים, Maryām, rendered Μαρία, Maria, in the Koine Greek of the New Testament; form of Hebrew מִרְיָם, Miryām, or Miriam, "wished for child", "bitter" or "rebellious".

References

[edit]- ^ Uraguchi, B. (1916). "The Bethany Family". The Biblical World. 48 (2): 101–114. doi:10.1086/475593. JSTOR 3142286. S2CID 144905453.

- ^ "Holy Shrines outside Jerusalem".

- ^ "Santa Maria de Betania of Miraculous Medal Parish - Molo, Philippines".

- ^ See the Gospel texts, and Schiller, Gertud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, pp. 158–59, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0853312702

- ^ a b Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2001 ISBN 978-88-209-7210-3), pp. 383, 398

- ^ "Saints Martha, Mary and Lazarus". usccb.org. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Carol Ann Newsom, Sharon H. Ringe, Jacqueline E. Lapsley (editors), Women's Bible Commentary, p. 532: "Although Eastern Orthodox Scholars never subscribed to this conflation of Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany and the unnamed sinner, Gregory The Great's interpretation cemented Mary Magdalene's reputation as a penitent sinner for most of her interpretive history in the West" (Westminster John Knox Press, 2012 Third Edition Revised and Updated, ISBN 978-0-664-23707-3)

- ^ 11:1–2

- ^ 12:3

- ^ John 11:1–2

- ^ a b Tenney, Merrill C. (1994). "John". In Kenneth L. Barker & John Kohlenberger III (ed.). Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House.

- ^ Jn 11:21, 32

- ^ Jn 11:33

- ^ Henry, Matthew (1706). Complete Commentary on the Whole Bible.

- ^ Jn 12:3

- ^ Jn 12:1–8

- ^ 26:6–13

- ^ 14:3–9

- ^ Mt 26:13, 14:9

- ^ Jn 11:38

- ^ Jn 11:39

- ^ a b "Mary", Easton's Bible Dictionary, 1897.

- ^ 7:36–50

- ^ Discussed in Van Til, Kent A. Three Anointings and One offering: The Sinful Woman in Luke 7.36–50 Archived 2012-07-07 at archive.today, Journal of Pentecostal Theology, Volume 15, Number 1, 2006, pp. 73–82(10). However, the author of this article does not himself hold to this view.

- ^ Hersey, Kim. The Two Debtors Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine, Wesley Center for Applied Theology, Northwest Nazarene University.

- ^ Lk 10:40

- ^ Liefeld, Walter L. (1994). "Luke". In Kenneth L. Barker & John Kohlenberger III (ed.). Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Publishing House.

- ^ Reid, Barbara E., "Mary of Bethany, a Model of Listening", L'Osservatore Romano, August 11, 2017, p. 6

- ^ a b c Pope, H. (1910). St. Mary Magdalen, in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ referenced in Jansen, Katherine Ludwig (2001). The making of the Magdalen: preaching and popular devotion in the later Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08987-4.

- ^ Rivera, John (2003-04-18). "John Rivera, "Restoring Mary Magdalene" in "Worldwide Religious News", The Baltimore Sun, April 18, 2003". Wwrn.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William, eds. (2003). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 3. Eerdmans. p. 447. ISBN 9789004126541.

- ^ Flader, John (2010). Question Time: 150 Questions and Answers on the Catholic Faith. Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-1-58979594-5.

- ^ About the Holy Myrrh-Bearing Women, Holy Myrrhbearers Women's Choir, Blauvelt, N.Y.

- ^ Righteous Mary the sister of Lazarus, Orthodox Church in America.

- ^ Mary & Martha, the sisters of Lazarus Archived 2009-10-26 at the Wayback Machine, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

- ^ "DECREE on the Celebration of Saints Martha, Mary and Lazarus in the General Roman Calendar (26 January 2021)". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

- ^ July commemorations in the Anglican Church, Oremus.com.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Raymond E. The Gospel According to John (I–XII): Introduction, Translation, and Notes. Anchor Bible Series, vol. 29. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966.

- Harrington, Daniel J. The Gospel of John. Liturgical Press, 2011.

External links

[edit]- M. G. Easton (1897). "Mary". Easton's Bible Dictionary.

- Catholic Encyclopedia 1910: under "Saint Mary Magdalene"

- Mary & Martha, the sisters of Lazarus, Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

- Circulo Santa Maria de Betania, group dedicated to the devotion of Saint Mary of Bethany in the Philippines