Trading Places

| Trading Places | |

|---|---|

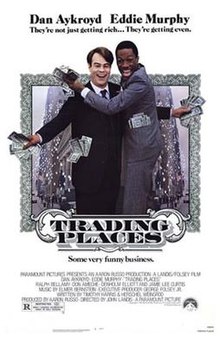

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Landis |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | Aaron Russo |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Paynter |

| Edited by | Malcolm Campbell |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $120.6 million |

Trading Places is a 1983 American comedy film directed by John Landis and written by Timothy Harris and Herschel Weingrod. Starring Dan Aykroyd, Eddie Murphy, Ralph Bellamy, Don Ameche, Denholm Elliott, and Jamie Lee Curtis, the film tells the story of an upper-class commodities broker (Aykroyd) and a poor street hustler (Murphy) whose lives cross when they are unwittingly made the subjects of an elaborate bet to test how each man will perform when their life circumstances are swapped.

Harris conceived the outline for Trading Places in the early 1980s after meeting two wealthy brothers who were engaged in an ongoing rivalry with each other. He and his writing partner Weingrod developed the idea as a project to star Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. When they were unable to participate, Landis cast Aykroyd—with whom he had worked previously—and a young but increasingly popular Murphy in his second feature-film role. Landis also cast Curtis against the intent of the studio, Paramount Pictures; she was famous mainly for her roles in horror films, which were looked down upon at the time. Principal photography took place from December 1982 to March 1983, entirely on location in Philadelphia and New York City. Elmer Bernstein scored the film, using Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's opera buffa The Marriage of Figaro as an underlying theme.

Trading Places was considered a box-office success on its release, earning over $90.4 million to become the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1983 in the United States and Canada, and $120.6 million worldwide. It also received generally positive reviews, with critics praising both the central cast and the film's revival of the screwball comedy genre prevalent in the 1930s and 1940s while criticizing Trading Places for lacking the same moral message of the genre while promoting the accumulation of wealth. It received multiple award nominations including an Academy Award for Bernstein's score and won two BAFTA awards for Elliott and Curtis. The film also launched or revitalized the careers of its main cast, who each appeared in several other films throughout the 1980s. In particular, Murphy became one of the highest-paid and most sought after comedians in Hollywood.

In the years since its release, the film has been praised as one of the greatest comedy films and Christmas films ever made despite some criticism of its use of racial jokes and language. In 2010, the film was referenced in Congressional testimony concerning the reform of the commodities trading market designed to prevent the insider trading demonstrated in Trading Places. In 1988, Bellamy and Ameche reprised their characters for Murphy's comedy film Coming to America.

Plot

[edit]Brothers Randolph and Mortimer Duke own a commodities brokerage firm, Duke & Duke Commodity Brokers, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They witness an encounter between their managing director—the well-mannered and educated Louis Winthorpe III, engaged to the Dukes' grandniece Penelope Witherspoon—and poor black street hustler Billy Ray Valentine. Valentine is arrested at Winthorpe's insistence after the latter assumes he is being robbed. Holding opposing views on the issue of nature versus nurture, the Dukes make a wager and agree to conduct an experiment to observe the results of switching the lives of Valentine and Winthorpe, two people in contrasting social strata.

Winthorpe is framed as a thief, drug dealer, and philanderer by Clarence Beeks, a man on the Dukes' payroll. He is fired from Duke & Duke, his bank accounts are frozen, he is denied entry to his Duke-owned home, and is vilified by his friends and Penelope. Winthorpe is befriended by Ophelia, a prostitute who helps him in exchange for a financial reward once he is exonerated to secure her own retirement. The Dukes post bail for Valentine, install him in Winthorpe's former job, and grant him use of Winthorpe's home. Valentine becomes well versed in the business, using his street smarts to achieve success, and begins to act in a well-mannered way.

During the firm's Christmas party, Winthorpe plants drugs in Valentine's desk, attempting to frame him, and brandishes a gun to escape. Later, the Dukes discuss their experiment and settle their wager for $1. They plot to return Valentine to the streets, but have no intention of taking back Winthorpe. Valentine overhears the conversation and seeks out Winthorpe, who has attempted suicide by overdosing. Valentine, Ophelia, and Winthorpe's butler Coleman nurse him back to health and inform him of the experiment. Watching a television news broadcast, they learn that Beeks is transporting a secret United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) report on orange crop forecasts. Remembering large payments made to Beeks by the Dukes, Winthorpe and Valentine decide to foil the brothers' plan to obtain the report early and use it to corner the market on frozen concentrated orange juice.

On New Year's Eve, the four board Beeks' train in disguise, intending to switch the original report with a forgery that predicts low orange crop yields. Beeks uncovers their scheme and attempts to kill them, but is knocked unconscious by a gorilla being transported on the train. The four dress him in a gorilla suit and cage him with the real gorilla. They deliver the forged report to the Dukes in Beeks' place and collect the payment intended for him. After sharing a kiss with Ophelia, Winthorpe travels to New York City with Valentine, pooling the money with the life savings of Ophelia and Coleman to carry out their plan.

On the commodities trading floor, the Dukes invest heavily in buying frozen concentrated orange juice futures contracts, legally committing themselves to purchase the commodity at a later date. Other traders follow their lead, driving the price up; Valentine and Winthorpe short-sell juice futures contracts at the inflated price. Following the broadcast of the actual crop report and its prediction of a normal harvest, the price of juice futures plummets. As the traders frantically sell their futures, Valentine and Winthorpe buy at the lower price from everyone except the Dukes, fulfilling the contracts they had short-sold earlier and turning an immense profit.

After the closing bell, Valentine and Winthorpe explain to the Dukes that they made a wager on whether they could get rich and make the Dukes poor at the same time, and Winthorpe pays Valentine his winnings of $1. When the Dukes prove unable to pay the $394 million required to satisfy their margin call, the exchange manager orders their seats sold and their corporate and personal assets confiscated, effectively bankrupting them. Randolph collapses holding his chest and Mortimer shouts at the others, demanding the floor be reopened in a futile plea to recoup their losses.

The now-wealthy Valentine, Winthorpe, Ophelia, and Coleman vacation on a luxurious tropical beach, while Beeks and the gorilla are loaded onto a ship bound for Africa.

Cast

[edit]- Dan Aykroyd as Louis Winthorpe III: a wealthy commodities director at Duke & Duke.[1]

- Eddie Murphy as Billy Ray Valentine: a street beggar and con man.[2]

- Ralph Bellamy as Randolph Duke: greedy co-owner of Duke & Duke, alongside his brother Mortimer.[1]

- Don Ameche as Mortimer Duke: Randolph's equally greedy brother.[1]

- Denholm Elliott as Coleman: Winthorpe's butler.[3]

- Jamie Lee Curtis as Ophelia: a prostitute who helps Winthorpe.[2]

- Kristin Holby as Penelope Witherspoon: the Dukes' grandniece and Winthorpe's fiancée.[4]

- Paul Gleason as Clarence Beeks: a security expert covertly working for the Dukes.[5]

As well as the main cast, Trading Places features Robert Curtis-Brown as Todd, Winthorpe's romantic rival for Penelope; Alfred Drake as the Securities Exchange manager;[6] and Jim Belushi as Harvey, a party-goer on New Year's Eve.[3] The film has numerous cameos, including singer Bo Diddley as a pawnbroker;[7] Curtis' sister Kelly as Penelope's friend Muffy; the Muppets puppeteers Frank Oz and Richard Hunt as, respectively, a police officer and Wilson, the Dukes' broker on the trading floor; and Aykroyd's former Saturday Night Live colleagues, Tom Davis and Al Franken, as train baggage handlers.[3]

Other minor roles include Ron Taylor as "Big Black Guy", American football player J. T. Turner as "Even Bigger Black Guy" who only says "Yeah!",[8] and Giancarlo Esposito as a cellmate.[6] Trading Places also features the final theatrically released performance of Avon Long who plays the Dukes' butler Ezra.[9] The gorilla is portrayed by mime Don McLeod.[10][11]

Production

[edit]Writing and development

[edit]In the early 1980s, writer Timothy Harris often played tennis against two wealthy, but frugal brothers who regularly engaged in a competitive rivalry and betting. Following one session, Harris returned home exasperated with the pair's conflict and concluded that they were "awful" people. The situation gave him the idea of two brothers betting over nature versus nurture in terms of human ability. Harris shared the idea with his writing partner Herschel Weingrod, who liked the concept. Harris also drew inspiration for the story from his own living situation; he lived in a rundown area near Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles. He described the area in grim terms as crime-ridden, where everyone either had a gun pointed at them or had been raped.[2]

Harris and Weingrod researched the commodities market for the script.[2] They learned of financial market incidents, including Russian attempts to corner the wheat market and the Hunt brothers' efforts to corner the silver market on what became known as Silver Thursday. They thought trading orange juice and pork bellies would be funnier because the public would be unaware such mundane items were traded.[12] Harris consulted with people in the commodities business to understand how the film's finale on the trading floor would work. The pair determined that the commodities market would make for an interesting setting for a film, as long as it was not about the financial market itself. They needed something to draw the audience in. It was decided to set the story in Philadelphia because of its connections to the founding of the United States, the American dream and idealism and the pursuit of happiness. This was tempered by introducing Billy Ray Valentine as a black man begging on the street.[2] The pair knew that the method of Winthorpe's and Valentine's financial victory could be confusing, but hoped that audiences would be too invested in the characters' success to care about the details.[12]

The script was sold to Paramount Pictures under the title Black and White. Then-Paramount executive Jeffrey Katzenberg offered the project to director John Landis. Landis disliked the working title,[2] but favorably compared the script to older screwball comedies of the 1930s by directors like Frank Capra, Leo McCarey, and Preston Sturges, which often satirized social constructs and social classes, reflecting the cultural issues of their time. Landis wanted his film to reflect these concepts in the 1980s;[2][13][14] he said the main updates were the addition of swearing and nudity.[13] Landis admitted that it took him a while to understand how Trading Places' finale worked.[2]

Casting

[edit]

Trading Places was developed with the intent to cast comedy duo Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder as Valentine and Louis Winthorpe III respectively.[2][13] The pair were in high demand following the success of their comedy film Stir Crazy (1980).[3] When Pryor was severely injured after setting fire to himself while freebasing cocaine, the decision was made to cast someone else.[2][15] Paramount Pictures suggested Eddie Murphy.[2] The studio was initially unhappy with Murphy's performance in his first film, the as-then-unreleased action-comedy 48 Hrs. (1982)—a film also conceived as a Pryor project.[16] However, that film was well received by preview test audiences, leading the studio to reverse its opinion.[2][13] Landis was unaware of Murphy, who had been gaining fame as a performer on Saturday Night Live. After watching Murphy's audition tapes, Landis was impressed enough to travel to New York City to meet with him.[2] Murphy said that he was paid $350,000 for the role; it was reported that the figure was as high as $1 million.[17][18]

Landis wanted Dan Aykroyd to serve as Murphy's co-star. He had worked previously with Aykroyd on the musical comedy film The Blues Brothers (1980); the experience had been positive. Landis said, "he could easily play [Winthorpe] ... you tell him what you want, and he delivers. And I thought he'd be wonderful." Paramount Pictures was less enamored with Aykroyd; executives believed that he performed better as part of a duo, as he had working with John Belushi. They felt that Aykroyd working alone would be akin to Bud Abbott, half of Abbott and Costello, working without Lou Costello and Aykroyd's recent films had fared poorly at the box office. Aykroyd agreed to take a pay cut for the role.[2]

The studio also objected to the casting of Jamie Lee Curtis. At the time she was seen as a "scream queen", primarily associated with low-quality B movies. Landis had worked previously with Curtis on the horror documentary Coming Soon, for which she had served as the host. She wanted to move away from horror films as she was conscious that the association would limit her future career prospects. She had turned down a role in the horror film Psycho II (1983) because of this. Her mother, Janet Leigh, had famously starred in Psycho (1960).[2] Curtis had performed recently in the slasher film Halloween II (1981) as a favor to director John Carpenter and producer Debra Hill; she was paid $1 million for that role, but received only $70,000 for Trading Places.[2] When asked if she had researched her role as a prostitute, Curtis jokingly remarked: "I'd love to say I went out and turned a couple of tricks on 42nd Street, but I didn't."[19] Curtis had long hair when she was cast; costume designer Deborah Nadoolman Landis suggested cutting her hair shorter for the film.[13]

For the greedy Duke brothers, Ralph Bellamy was the first choice for Randolph.[3] For Mortimer, Landis wanted to cast an actor famous in the 1930s or 1940s who was not associated with playing a villain. His first choice was Ray Milland, but the actor was unable to pass a physical test to qualify for insurance while filming. As the start date for filming loomed, Landis thought of Don Ameche. The casting director claimed that Ameche was dead.[13] Landis was skeptical of this and contacted the Screen Actors Guild in an attempt to locate him. They confirmed that Ameche had no agent, and his royalty payments were being forwarded to his son in Arizona. Landis accepted this as evidence that Ameche was deceased. However, after hearing of Landis' search, one of the Paramount Studios' secretaries mentioned that they saw Ameche regularly on San Vicente Boulevard in Santa Monica, California. Landis called directory assistance to locate a "D. Ameche" in the area and made contact.[2] Ameche had not featured in a film for over a decade; when asked why, he said that no one had offered him film work.[2][20] The studio did not want to pay Ameche what Milland had been offered; as Ameche was financially independent and in no need of work, he refused to take the part until he received equal pay.[21][22] Landis claimed that the studio reduced the film's budget, frustrated at Ameche's casting after a long absence from film work.[13]

John Gielgud and Ronnie Barker were considered for the role of Winthorpe's butler, Coleman. Barker refused to act if it involved filming more than 7 miles (11 km) from his home in the United Kingdom.[3][13] G. Gordon Liddy, a central figure in the Watergate political scandal of the early 1970s, was offered the role of corrupt official Clarence Beeks. Liddy was interested in the offer until he learned that Beeks becomes the romantic partner of a gorilla. Paul Gleason took the role; his character reads a copy of Liddy's autobiography Will while riding the train.[3] Don McLeod portrayed the gorilla; he had already become popular for his performances as a gorilla in American Tourister commercials, which led to film appearances.[10][11]

Filming

[edit]

Principal photography began on December 13, 1982.[4][23] The budget was estimated to be $15 million.[24][a] Filming took place on location in Philadelphia and New York City.[2][4] Robert Paynter and Malcolm Campbell served, respectively, as the film's cinematographer and editor.[25][26]

The script underwent minor changes throughout filming; some improvisation was also encouraged. Changes were normally discussed in advance, but on other occasions, ad-libbed dialogue was considered funny enough to keep. Examples of ad-libs retained in the film include Valentine comparing Randolph to Randy Jackson of The Jackson 5 and demonstrating his "quart of blood" technique in jail.[14][23] Murphy liked Trading Places' script; he felt it was unlike 48 Hrs., which he said had been saved by director Walter Hill. Even so, he changed many of his own lines because he said that a white writer writing for a black person would use stereotypical dialogue like "jive turkey" and "sucker", and he could write his lines to sound authentic.[23] Weingrod said the studio objected to Murphy's line, "Who put their Kools out on my Persian rug?" They believed it was racist because the Kool cigarette brand was targeted mainly at African Americans; Murphy restored the line.[27] Ophelia pretending to be a European exchange student to fool Beeks was also improvised; Curtis used a mix of German attire with a Swedish accent because she could not perform a German accent.[3]

The first fifteen days of filming were spent in Philadelphia.[4] Landis described the weather as freezing. While filming the scene where Randolph and Mortimer collect Valentine from jail, Landis was positioned in a towing truck that pulled the Rolls-Royce carrying Ameche, Bellamy and Murphy. Landis wore a thick parka to stay warm, and the actors had a space heater in their vehicle; Landis listened to their dialogue via radio. Describing the filming of the scene, Landis recalled a jovial discussion between Ameche, Bellamy, and Murphy: Bellamy said that Trading Places was his 99th film; Ameche said it was his 100th. Murphy informed Landis that "between the three of us we've made 201 films!"[13] Filming locations in Philadelphia included townhouses in Center City that served as the Winthorpe home exterior, and the Philadelphia Mint (now the Community College of Philadelphia) which served as the police station's exterior.[4][28] The exterior and lobby of the Wells Fargo Building serve as the respective exterior and lobby of Duke & Duke.[2][29]

The Duke & Duke upstairs offices were filmed inside the upstairs of the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York.[2] Murphy's character, pretending to be crippled, is introduced in Rittenhouse Square. The nearby Curtis Institute of Music, shown as the exterior of the Heritage Club, is seen adjacent to Rittenhouse Park in the film's opening.[4][30][31] The interior was filmed at the then-abandoned New York Chamber of Commerce Building.[2][32] Independence Hall is also featured.[30] During filming in Philadelphia, Murphy was so popular that a police officer had to be stationed outside of his trailer to control the crowds.[33]

Filming moved to New York City in January 1983; many of the interior scenes were filmed there.[2][4] In late January, two holding cells on the 12th-floor of the New York Supreme Court building at 100 Centre Street were taken over for filming. Empty lockups in police administration buildings would normally be in use but because of the financial investment the production had made filming in the city, the mayor's office agreed to accommodate Landis' request; the studio paid for any expenses incurred. The New York Times reported that for years the Corrections Department had failed to deliver prisoners on time for trials and arraignments; despite this, they moved nearly 300 prisoners through the 12th-floor before 9 a.m. on the day of filming.[34]

The scene where Valentine and Winthorpe enact their plan against the Dukes was filmed at the COMEX commodity exchange located inside 4 World Trade Center. The lack of windows gave the appearance the floor was situated below ground, but it was actually on a high floor. The scene was scripted to take place at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, but the filmmakers were unable to secure permission to film there.[2] The scene was shot over approximately 3–4 hours a day over two days.[2] It was scheduled to take place during a weekday, but Aykroyd's and Murphy's presence on the floor distracted the active traders and over $6 billion of trading had to be halted; filming was rescheduled for a weekend.[4] A majority of the people on screen are actual traders, along with some extras. Landis said the traders in the film were less physically rough with each other than they were during normal trading.[2][4] Landis also performed some guerrilla filmmaking there for additional footage.[2] Ameche was opposed to using foul language and often apologized in advance to his crewmates for what he was scripted to say; he only performed one take of his final scene where he shouts "fuck him", referring to Randolph.[3] The final scene shot was of the main characters celebrating on a beach; this was filmed on Saint Croix island in the United States Virgin Islands.[4][35] Principal photography concluded on March 1, 1983, after 78 days.[4]

Music

[edit]Elmer Bernstein composed the score for Trading Places.[36] He and Landis had collaborated previously on several films including The Blues Brothers and the horror-comedy An American Werewolf in London (1981).[37] Landis conceived of the idea to use the opera buffa The Marriage of Figaro by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart as the underlying theme for the score. He had used classical music in his previous films to represent the upper classes and felt that it would be fitting for the pompous elites of the financial industry.[38][39] The Marriage of Figaro concerns the story of a servant who is wronged by his wealthy employer, Count Almaviva, and takes his revenge by unraveling the count's own machinations.[40]

Bernstein created his own arrangements of the music to reflect the differing emotions of each scene.[38][40] The overture of Marriage of Figaro plays over the film's opening.[36] The score also includes arrangements of Pomp and Circumstance Marches by Edward Elgar, and Mozart's Symphony No. 41.[36][38] Trading Places features songs including: "Do You Wanna Funk" by Sylvester and Patrick Cowley, "Jingle Bell Rock" by Brenda Lee, "The Loco-Motion" by Little Eva, and "Get a Job" by the Silhouettes.[4]

Release

[edit]Context

[edit]The summer of 1983 (June–September) was predicted to surpass the previous year's record-breaking $1.4 billion in theater tickets sold. The season featured expected hits such as the third installment in the Star Wars series, Return of the Jedi, Superman III, and the latest James Bond film Octopussy. Over 40 films were scheduled for release over the 16-week period. Studios had to strategize their releases to avoid damaging their own films' performances by pitting them against better-performing competition.[41] Paramount Studios opted to release Trading Places at the start of summer, as those films expected to do well would benefit from being in theaters longer during this busy period. Comedy films were considered counterprogramming that attracted audiences who had already seen, or were not interested in, the major film releases that were mainly focused on science-fiction and superheroes. Trading Places was released between Return of the Jedi in May and Superman III in mid-June. While sequels were expected to do well having the advantage of a built-in audience, Trading Places was predicted to be successful based on its cast.[41]

Box office

[edit]In the United States (U.S.) and Canada, Trading Places received a wide release on Wednesday, June 8, 1983, across 1,375 theaters.[42][43] The film earned $1.7 million leading into its opening weekend when it earned a further $7.3 million—an average of $5,344 per theater. Trading Places finished as the number three film of the weekend behind Octopussy ($8.9 million), also making its debut that weekend, and Return of the Jedi ($12 million), which was in its third week of release.[44] The film retained the number three position in its second weekend with a further gross of $7 million, behind Return of the Jedi ($11.2 million), and the debuting Superman III ($13.3 million).[45] In its third weekend, it fell to fifth place with $5.5 million, behind the debuting science-fiction horror Twilight Zone: The Movie ($6.6 million) and sex comedy Porky's II: The Next Day ($7 million), Superman III ($9 million), and Return of the Jedi ($11.1 million).[46]

While the film never claimed the number one box office ranking, it spent seventeen straight weeks among the top ten-highest-grossing films.[47] By September, it was the fourth-highest-grossing film of the year with $80.6 million,[48] and by the end of its theatrical run, Trading Places earned an approximate box office gross of $90.4 million.[43][b] It finished as the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1983, behind Paramount Studio's surprise hit, the romantic drama Flashdance ($90.46 million), the comedy-drama Terms of Endearment ($108.4 million), and Return of the Jedi ($309.2 million).[48][49][50] Estimates by industry experts suggest that as of 1997, the box office returns to the studio—minus the theaters' share—was $40.6 million.[51] Outside of the United States and Canada, Trading Places is estimated to have earned a further $30.2 million, bringing its worldwide gross to $120.6 million.[52][c]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

Trading Places received generally positive reviews from critics.[2] Reviewers compared it to the socially conscious comedies of the 1930s and 1940s, like My Man Godfrey (1936), Easy Living (1937), Christmas in July (1940), and Sullivan's Travels (1941) by directors like Preston Sturges, Frank Capra, and Gregory La Cava.[d] Janet Maslin said that the "likable" film owed a debt to the screwball comedy genre. She continued, "Preston Sturges might have made a movie like Trading Places – if he'd had a little less inspiration and a lot more money."[42] Gary Arnold said the film was too inconsistent to be compared to those older films.[55] Vincent Canby said that the screwball style had been updated for the "existential hipness" of the 1980s, but the film lacked the same morality tale the genre often espoused that money is not important. Instead, the characters do not dismantle or expose the corruption of the financial system, they just take revenge on the Dukes, obtaining extreme wealth in the process. Even so, he concluded the film was one of the best American comedies released in a long time.[53] Maslin agreed that the film was too enamored with the wealthy institutions it satirized to provide a true criticism of the system and its failings. She called it the American Dream in film form.[42]

Dave Kehr said that though the film pays homage to screwball comedies, it stripped the concept of all but the "crudest audience-gratification moments" and avoided exploration of the genre's moral conflicts.[56] In Variety's review, the reviewer concluded that the middle segment of the film lacked humor.[25] People said that the ending was perfectly presented, but Arnold considered it to be confusing and reliant on the audience's knowledge that the "heroes" were being heroic to compensate for a lack of clarity in their actions.[55][57] He continued that even as a farcical film, the events were too unbelievable.[55] Roger Ebert said the ending was inventive for not involving a "manic chase".[54] He appreciated that Trading Places did not rely on obvious racial plot points or employ sitcom tropes for the social-status swaps of Winthorpe and Valentine. He commended the focus on developing each character so that they were funny because of their individual quirks and personalities. He concluded that this required a deeper script than would normally be developed for a comedy.[54]

The cast were all generally praised.[25][42][54] Maslin called it a strange but well-cast film representing multiple Hollywood generations.[42] Ebert said that what could have been stereotypical characters were elevated by the actors and the writing, adding that Murphy and Aykroyd made a "perfect" team.[54] Canby said that Murphy demonstrated why he was the most successful comedian in the last decade.[53] Several reviewers compared his role to that in 48 Hrs.;[58][55] Arnold said that Trading Places was evidence that Murphy's successes were not a fluke, and that Murphy demonstrated an "exhilarating comic authority".[55] Canby said that Trading Places gave Murphy an opportunity to demonstrate the range of his abilities in a "lithe, graceful, uproarious" performance.[53]

Reviewers agreed that the film featured Aykroyd's best performance to date.[53][55] People said that if audiences had given up on Aykroyd following the failures of Neighbors (1981) and Doctor Detroit (1983), his career was revitalized by Trading Places.[57] Canby said that Aykroyd gave a more consistent performance than in his previous roles. He said that Aykroyd had demonstrated that his success was not dependent upon his partnership with John Belushi.[53] Arnold said that Aykroyd worked best when he shared a central role with another star.[55] Rita Kempley said that his relationship with Murphy was just as enjoyable as his one with Belushi.[58]

Variety noted that the supporting cast in Bellamy, Ameche, Elliott and Curtis were essential to the film.[25] Reviewers said that Curtis brought a deft comic ability to the role.[53][55] Arnold called the role "stale" and "predictable" but felt Curtis offered an "infectious" humor that earns the audience's support.[55] People said that she had a significant appeal, and Kempley called her both "curvaceous" and "vivacious".[58][57] Canby said that in her first major non-horror role, Curtis performed with "marvelous good humor".[53] Kehr criticized Landis for often turning his heroines into "busty bunnies", and said that he had treated Curtis the same way.[56] Ebert called Bellamy and Ameche's casting a "masterstroke".[54] Canby said the pair had well-written roles that were supported by their comic performances. He continued that Ameche was as funny in Trading Places as he was always meant to be.[53]

People said that the film works because Landis demonstrated a "remarkable" restraint.[57] Canby said Landis had shown that he could direct a precise comedy as well as special effects-laden fare.[53] Arnold disagreed saying Landis' comedic timing was less precise than in his previous work and that he lacked the skill to handle the source material properly.[55] People said that Harris and Weingrod had developed a well-written script,[57] but Arnold said they had failed to update the screwball genre to tackle social contrasts in a similar way.[55]

Accolades

[edit]At the 41st Golden Globe Awards in 1984, the film received two nominations: Best Musical or Comedy (losing to romantic drama Yentl) and Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy for Murphy who lost to Michael Caine's performance in the comedy drama Educating Rita.[59] At the 56th Academy Awards, Bernstein was nominated for Best Original Score; he lost to Michel Legrand and Alan and Marilyn Bergman, who scored Yentl.[60]

The 37th British Academy Film Awards named Elliott and Curtis the Best Supporting Actor and Best Supporting Actress, respectively. Harris and Weingrod were nominated for Best Original Screenplay; they lost to Paul D. Zimmerman for the 1982 black comedy The King of Comedy.[61]

Post-release

[edit]Performance analysis and aftermath

[edit]

As predicted, the 1983 summer film season broke the previous year's record with over $1.5 billion worth of tickets sold. It was seen as a substantial increase in spite of increased ticket prices.[48] Even so, the year was a mixture of unexpected successes and disappointments. Films like Superman III and the action comedies Smokey and the Bandit Part 3 and Stroker Ace had failed at the box office. The science fiction comedy The Man with Two Brains featuring an established star in Steve Martin had also underperformed.[62] Conversely, Flashdance was an unexpected hit and the third highest-grossing film of the year, despite a negative critical reception.[48] In September, The New York Times wrote that Trading Places was the only film of the fifteen top-grossing films that could be recommended without reservation.[62] The film was well-received critically and considered a significant commercial success, along with Flashdance and Return of the Jedi.[63][62] Then-production vice president of MGM/UA studio Peter Bart described it as a "gimmick" film that focused on a "high-concept" over story and characterization. Bart believed its success triggered a negative trend that resulted in him receiving numerous film pitches—often a mix of the high-concept nature of Trading Places with a Flashdance-inspired breakdancing or gym setting.[64] Harris recalled people asking if the producer Aaron Russo or Katzenberg had created the idea and just paid him to write it. He said he knew it was a success because people were trying to take credit for it.[2]

Trading Places is considered responsible for launching, changing, or re-launching the careers of many of its stars.[2] Murphy's success was significant. He rose from a TV comedian to a superstar with two of the most successful films of the year.[65] Industry experts voted him as the biggest box-office star after Clint Eastwood. No other African-American actor had achieved a comparable level of success before him.[65] It was reported that Murphy earned up to $1 million for Trading Places, but by his third film, Beverly Hills Cop (1984), he commanded a $3 million salary. This was considered a top-tier salary reserved for the most popular movie stars.[18]

Shortly after Trading Places' release, Paramount Pictures signed Murphy to a $25 million five-film exclusive contract—one of the biggest deals ever with an actor at the time. The studio also agreed to finance his Eddie Murphy Productions studio.[18][66] Murphy was among several young stars who emerged that year, including Matthew Broderick, Tom Cruise, and Michael Keaton, who were all in their 20s. This reflected the fact that average audiences were aging and now in their late teens to late 20s, and led to a shift in focus away from making films targeted mainly at children.[64] His rapid rise to fame led to Murphy leaving Saturday Night Live the following year; he said he had grown to dislike the job and felt he was resented for his success.[23]

After a series of failures, Trading Places revitalized Aykroyd's career.[67] Throughout the 1980s, he went on to star in the blockbuster phenomenon Ghostbusters (1984),[68] Spies Like Us (1985) and Dragnet (1987). He earned an Academy Award nomination for his performance in the comedy-drama Driving Miss Daisy (1989).[69][70] Trading Places is considered Curtis's breakout performance, allowing her to move into films outside the horror genre; actor John Cleese cast Curtis in the 1988 heist comedy A Fish Called Wanda specifically because of her performance in Trading Places.[2][19][71] Curtis said Landis had "single-handedly changed the course of my life by giving me that part."[2] After not having worked in film for more than a decade, Ameche followed Trading Places with the 1985 comedy-drama Cocoon, for which he won his first and only Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[2][21]

Landis continued to work as a director but suffered setbacks following a lawsuit over the accidental deaths of several actors on a segment he directed for Twilight Zone: The Movie and a succession of moderately successful films.[72][73] According to Murphy, he hired Landis to direct his 1988 comedy Coming to America to help support Landis's career. The pair had a falling out on the set of that film; even so, they collaborated again on Beverly Hills Cop III (1994).[13][72][74] Harris and Weingrod were elevated to prominence as writers.[2] They later sued Trading Places' producer, Aaron Russo, for an agreed upon 0.5% of the producer profits share, estimated to be worth $150,000; the outcome of this lawsuit is unknown.[4]

Home media

[edit]In the early 1980s, the VCR home video market was gaining popularity rapidly. In previous years, VHS sales were not a revenue source for studios, but by 1983 they could generate up to 13% of a film's total revenue; the North American cassette rights could generate $500,000 alone.[75] Trading Places was released on VHS in May 1984, priced at $39.95.[76] Paramount distributed its own cassettes and priced them significantly lower than the standard $80 price to promote home user VCR adoption. A successful film was expected to earn between $5 million and $10 million on the home video market.[75] In the rental market, Trading Places was one of the more popular releases in May, alongside the action thriller Sudden Impact.[75] Paramount signed an exclusive deal to show its movies, including Trading Places, on the Showtime TV network for approximately $500 million; this was seen as an attempt by Paramount to damage the network monopoly held by HBO that the studio saw as financially unfavorable.[75][77]

Trading Places was first released on DVD in October 2002.[78] A Special Collector's Edition (also known as the "Looking Good, Feeling Good" edition) was released in 2007 on DVD, Blu-ray, and HD DVD. This edition included deleted scenes, details on the film's production, including discussions with the cast and crew, 1983 promotional interviews, and interviews with financial experts about the film.[79][80] The film was also released in a pack that included Coming to America.[81] To celebrate the film's 35th-anniversary in 2018, a special edition was released containing a Blu-ray and digital version of the film, and behind-the-scenes featurettes.[82] A limited-edition release of Bernstein's score was made available in 2011. Only 2,000 copies were released by La-La Land Records.[83]

Analysis

[edit]Ending explained

[edit]Several publications have attempted to explain exactly how Valentine and Winthorpe make a large sum of money on the commodities market while simultaneously bankrupting the Dukes.[84][85] The fake crop report created by Valentine and Winthorpe indicates to the Dukes that the orange crop will be poor, making the limited stock more valuable.[1][84][85] The Dukes attempt to buy up as many Frozen Concentrated Orange Juice (FCOJ) futures contracts as possible to corner the market—effectively owning a substantial enough number of contracts that they are able to control the price of FCOJ. The other traders realize what the Dukes are doing and join in buying futures.[84][85] This demand significantly inflates the price to $1.42 per pound—each future represents several pounds of FCOJ. Winthorpe and Valentine begin selling futures at this inflated price, believing it to be the peak price; the contracts will require them to supply FCOJ in April.[1][85] Anticipating that the crop report will cause the value of FCOJ to rise far above $1.42, the other brokers purchase heavily from the pair.[1][84][85]

Once the real crop report is published indicating that the orange crop will be normal and there will be no shortage of FCOJ, the value of the futures plummets as the traders desperately attempt to sell their futures and limit their financial losses.[84][85] Winthorpe and Valentine then buy back the futures from the traders—except for the Dukes' trader Wilson—at the lower price of 29 cents a pound.[84][85] The difference is their profit. Effectively, they have sold FCOJ which they do not have at a high price and bought it back at a lower price, earning them a profit and eliminating the need to fulfil any contracts.[85] Meanwhile, the Dukes have bought a significant number of FCOJ futures, around 100,000 contracts or 1.5 million pounds of FCOJ and have been unable to sell any of them. When trading closes, they must meet the margin call—essentially a deposit—for holding the futures contracts. In addition to their basic financial loss from buying futures at up to $1.42 that are now worth only 29 cents, the margin call for holding the futures gives them a total loss of $394 million,[e] which they do not have, requiring the sale of all of their assets.[86]

Thematic analysis

[edit]

The central storyline of Trading Places—a member of society trading places with another whose socio-economic status stands in direct contrast to his own—has often been compared to the 1881 novel The Prince and the Pauper by Mark Twain.[54][87][88] The novel follows the lives of a prince and a beggar who use their uncanny resemblance to each other to switch places temporarily; the prince takes on a life of poverty and misery while the pauper enjoys the lavish luxuries of royal life.[89] The Prince and the Pauper is seen as a classic tale of American literature; Trading Places adds a twist by casting an African-American as the pauper raised up in status, playing on fears of black usurpation and appropriation.[88] The film has also been compared to Twain's 1893 short story The Million Pound Bank Note, in which two brothers bet on the outcome of giving an impoverished person an unusable million-pound bank-note.[1][3] The choice to use Mozart's opera buffa The Marriage of Figaro also adds meaning. The opera tells the tale of a servant, Figaro, who foils the plans of his wealthy employer to steal his fiancée. When Winthorpe is driven to work during the film's opening, he hums "Se vuol ballare", an aria from The Marriage of Figaro, in which Figaro declares he will overturn the systems in place. This foreshadows Winthorpe's eventual efforts to do the same to the Dukes.[3][90]

The main theme of Trading Places is the consequences of wealth or the lack thereof. Both extremes are depicted by those living in opulent luxury and those trapped in a culture of poverty—a concept arguing that poor people adopt certain behaviors that keep them poor.[1] Harris has described the story as a satire of greed and social conventions, but in the end, the good guys win by becoming extremely rich.[2] Economic inequality is demonstrated by the wealthy who live in luxury. They are completely removed from those whose lives are affected by poverty. This is demonstrated by the Dukes' bet, showing their own sense of superiority over, and disregard for, the lives of those beneath them, even Winthorpe. Their only reward for the bet is personal pride.[1] Author Carolyn Anderson noted that films often feature an "introduction" scene for characters elevated above their station, like Valentine, to help them understand the rules of their new world. Conversely, there is rarely a complementary scene for those subjected to downward mobility.[91]

Vincent Canby said that although the film is an homage to social satire screwball comedies of the early 20th century, Trading Places is a symbol of its time. Where the earlier films espoused the benefits of things other than money, Trading Places is built around the value of money and those who aspire to have it. The heroes win by making lots of money; the villains are punished by becoming part of the impoverished. The heroes' reward is escaping to a tropical island, completely divorced from the poverty-stricken neighborhoods that had previously been their home.[53][92][93] Money is demonstrably a solution to all of the problems raised in the film, and when it is taken away, it is shown that people quickly resort to a basic criminal nature.[1] Stephen Schiff wrote that it can be seen as an example of supply-side economics, alongside films like the comedies Arthur (1981) and Risky Business (1983). While seemingly supporting left-leaning political concepts by arguing that given an equal platform a street-hustler like Valentine can perform Winthorpe's job equally well, Schiff argued that the film was still "unconsciously promoting Reaganism" where the accumulation of wealth is highly valued.[92] Harris described one incident where a person told him they had obtained a career in finance because of Trading Places; Harris said that this was counter to the film's message.[2]

David Budd said Trading Places defies expectations of racial stereotypes. Randolph's attempts to prove nurture wins over nature demonstrates that Valentine, given the same advantages as Winthorpe, is just as capable, and leaves behind the negative aspects of his former, unfair life.[87] Even so, once the Dukes' bet is complete, Mortimer reveals his intent to return Valentine to poverty, saying, "Do you really believe I would have a nigger run our family business?"; Randolph concurs, "Neither would I".[93] Budd concluded the film is a "message loudly asking for a reassessment of prejudice, and for level playing fields".[87] Hernan Vera and Andrew Gordon argue racial stereotypes are enabled with the permission of the only black main character. As part of their revenge against the Dukes, Winthorpe disguises his identity by donning blackface makeup, an act enabled by Valentine who has helped loosen up this strait-laced character. Because Valentine allowed it, it makes the act acceptable. This requires Valentine to accept and support Winthorpe despite having numerous reasons to dislike him, including originally getting Valentine wrongly arrested and then later trying to frame Valentine to reclaim his old job. Even so, Valentine befriends Winthorpe and helps him get revenge on the Dukes, the old establishment characters who demonstrate explicit racism. The film requires Valentine to act "white", performing as is expected of him to survive in the Dukes' world.[94]

Schiff argues that because the film identifies money as the most valuable entity, this in turn means that Ophelia is only valuable as a prostitute because she is financially intelligent.[92] Hadley Freeman said Ophelia is an example of the Smurfette principle, a female character in an otherwise male ensemble cast who exists to be pretty and rescued by men.[95] However, it is Ophelia who rescues Winthorpe, helping him to survive his new lowered-state.[93] Neal Karlen said Ophelia becomes a real person after telling Louis: "All I've got going for me in this whole, big, wide world is this body, this face, and what I've got up here [referring to her brain]".[96]

Trading Places also employs several conventions of its Christmas setting to highlight the individual loneliness of the main characters, in particular, Winthorpe. On Christmas Eve he humiliates himself in front of his former bosses, unwittingly losing his opportunity for his swap with Valentine to be undone by having become a criminal. While waiting outside a store, a dog urinates on him.[97][98] He attempts suicide and only fails because the gun does not fire; then it begins to rain on him. The following day offers a Christmas redemption and a change of fortune as Winthorpe is integrated into the non-traditional family unit of Coleman, Ophelia and Valentine.[1][97]

Legacy

[edit]Along with the impact their respective roles had on its stars' careers,[2] Trading Places is considered one of the best comedy films ever made and part of the canon of American comedies.[f] In a 1988 interview, Aykroyd said that he considered it among his "A-tier" films, along with Ghostbusters, Dragnet, The Blues Brothers, and Spies Like Us.[103]

Bellamy and Ameche reprised their Duke characters for Murphy's 1988 film Coming to America. Murphy portrays the affluent Prince Akeem who hands the now-homeless brothers a large sum of cash. Mortimer tells Randolph that it is enough to give them a new start.[3] Of the two films, Murphy has said that while he "loves" Trading Places, he prefers Coming to America because it allowed him to portray multiple characters.[104] The 2021 sequel Coming 2 America also references the Dukes, revealing they used Akeem's donation to rebuild their business.[105][106]

In 2010, nearly 30 years after its release, the film was cited in the testimony of Commodity Futures Trading Commission chief Gary Gensler regarding new regulations on the financial markets. He said:

We have recommended banning using misappropriated government information to trade in the commodity markets. In the movie Trading Places, starring Eddie Murphy, the Duke brothers intended to profit from trades in frozen concentrated orange juice futures contracts using an illicitly obtained and not yet public Department of Agriculture orange crop report. Characters played by Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd intercept the misappropriated report and trade on it to profit and ruin the Duke brothers.[107]

The testimony was part of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act designed to prevent insider trading on commodities markets, which had previously not been illegal. Section 746 of the reform act is referred to as the "Eddie Murphy rule".[1] An anonymous seller sold off their portion of the royalties earned from the film for $140,000 in 2019. At the time, the share was generating an average of $10,000 per annum.[108][109] A musical adaptation of Trading Places debuted at the Alliance Theater in Atlanta, Georgia, on June 4, 2022.[110]

Critical reassessment

[edit]Trading Places is considered one of the best comedies of the 1980s and one of the best Christmas films.[111][112][113] In 2015, the screenplay was listed as the joint thirty-third funniest on the WGA's 101 Funniest Screenplays list, tied with Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986).[102][114] In 2017, the BBC polled 253 critics (118 female, 135 male) from 52 countries on the funniest film made. Trading Places came seventy-fourth, behind The Nutty Professor (1963) and The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! (1988).[101] Several publications have named it one of the best films of the 1980s, including: number eight by IFC;[115] number 17 by MTV;[116] number 37 by USA Today;[111] and number 41 by Rotten Tomatoes.[112] It has also been listed as one of the best comedy films ever by publications including: number 16 by Time Out;[117] number 26 by Rotten Tomatoes;[99] and number 48 by Empire.[100]

Although the film's story takes place over several weeks leading up to and after Christmas, Trading Places is regarded as a Christmas film.[1][98] In 2008, The Washington Post called it one of the most underrated Christmas films.[118] The Atlantic described it as a less traditional Christmas film, but one whose themes remain relevant, particularly regarding the divide between the wealthy and poor.[1] It has appeared on several lists of the best Christmas films, including: number 5 by Empire;[119] number 12 by Entertainment Weekly;[120] number 13 by Thrillist;[121] number 23 by Time Out;[122] number 24 by Rotten Tomatoes (based on overall critical scores);[113] number 45 by Today;[123] and unranked by Country Living[124] and The Daily Telegraph.[125] It has been a popular Christmas film on TV in Italy since its television debut in 1986, generally played on Christmas Eve.[126]

Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 88%, based on 52 reviews, with an average rating of 7.5/10. The site's consensus states: "Featuring deft interplay between Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd, Trading Places is an immensely appealing social satire".[127] Metacritic gave the film a score of 69 out of 100, based on 10 critics, which indicates "generally favorable reviews".[128]

In the years followings its release, some critics have praised the film while highlighting elements that they believe aged poorly, including racial language, the use of blackface, and the implied rape of Beeks by a gorilla.[g] The film's use of the word "nigger", said during Mortimer's statement that he will never allow Valentine to run his family business, is sometimes censored in TV broadcasts. Todd Larkins Williams, director of the 2004 documentary The N-Word, said that it is a critical scene that should not be censored. He considered it dangerous to pretend a word never existed as in turn other negative events could also be ignored.[129] GQ argued that its social commentary remained relevant in spite of these elements.[130] In 2020, Trading Places was one of 16 films that had a disclaimer added by British broadcaster Sky UK. The disclaimer read, "This film has outdated attitudes, language, and cultural depictions which may cause offence today".[131]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The 1983 budget of $15 million is equivalent to $45.9 million in 2023.

- ^ The 1983 United States and Canada box office gross of $90.4 million is equivalent to $277 million in 2023.

- ^ The 1983 worldwide box office gross of $120.6 million is equivalent to $369 million in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[42][53][54][55]

- ^ The $394 million the Dukes lose is equivalent to $1.21 billion in 2023.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[2][99][100][101][102]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[1][95][129][130]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o White, Gillian B.; Lam, Bourree (December 25, 2015). "Trading Places: A 1983 Christmas Comedy That's Still Surprisingly Relevant". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Wile, Rob (June 27, 2013). "It's The 30-Year Anniversary Of The Greatest Wall Street Movie Ever Made: Here's The Story Behind It". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Drumm, Diana (June 8, 2013). "'Trading Places': More Than 7 Things You May Not Know About The Film (But We Won't Bet A Dollar On It)". IndieWire. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Trading Places". AFI.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Weintraub, Steve (May 30, 2006). "Mr. Beaks Says Goodbye to Clarence Beeks". Collider. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Trading Places (1983)". BFI.org.uk. Archived from the original on June 11, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Susman, Gary (July 12, 2013). "The 14 Craziest Musician Acting Cameos". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Moran, Malcolm (June 11, 1983). "Players; J.T. Turner Adopts New Role For A Film". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Fraser, C. Gerald (February 17, 1984). "Avon Long, Actor And Singer In Theater And Film 50 Years". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Barrett, Paul M. (July 12, 1983). "Life in the Gorilla Suit". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Lois (February 14, 1983). "Life Has Been Lucrative for Don McLeod Since a Luggage Company Made a Monkey Out of Him". People. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b "Guy Who Wrote 'Trading Places' Responds To Our Show About His Movie". NPR. July 24, 2013. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j de Semlyen, Nick (May 26, 2016). "'80s heroes: John Landis". Empire. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Edgers, Geoff (October 15, 2015). "Not just Bill Cosby: Eddie Murphy also didn't want to play Stevie Wonder at 'SNL 40'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Izadi, Elahe (August 30, 2016). "Remembering Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor, a magical and complicated comedy duo". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Kart, Larry (April 7, 1985). "Eddie Murphy: Comedy's Supernova Sends Humor Into A Different". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Conconi, Chuck (March 18, 1987). "Personalities". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Gary (July 31, 1983). "Murphy &". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Wallace, Carol (August 22, 1983). "Beware: Soft Shoulders—Jamie Lee Curtis' Career Has Changed Course". People. Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Chase, Chris (June 17, 1983). "At The Movies; Their credits include a mad computer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Richard (October 23, 1988). "Forever Ameche". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Sanders, Richard (September 2, 1985). "In the Sleeper of the Summer, Cocoon's Don Ameche Catches Hollywood's Younger Sex Symbols Napping". People. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Johns, Lindsay (April 12, 1984). "Eddie Murphy Leaves Home". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ "Box Office Information for Trading Places". The Wrap. Archived from the original on September 19, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Trading Places". Variety. January 1, 1983. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Bergan, Ronald (November 18, 2010). "Robert Paynter obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "AFF At Home: Comedy Q&A With Herschel Weingrod". austinfilmfestival.com. May 4, 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "About – Philadelphia Mint". treasury.gov. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ Fenn, Mike (July 19, 2016). "Phillywood: 7 key sites in Philly movie history". Metro.us. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ a b "27 Movies and TV Shows Starring Philadelphia". Visit Philadelphia. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Gralish, Tom (April 14, 2011). "The Curtis Symphony Orchestra". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Outdoor Film Screening: Trading Places". Princeton University Art Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Flippo, Chet (January 31, 1983). "Muscling in on Movies with 48 Hrs., Eddie Murphy May Take Richard Pryor's Crown". People. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Herman, Robin; Johnson, Laurie (January 26, 1983). "New York Day By Day". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "St. Croix". filmusvi.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Trading Place −3. Trading Place". Classic FM. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Celebrate Hollywood legend Elmer Bernstein with a magnificent new show". Royal Albert Hall. November 3, 2016. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Trading Places". Filmtracks.com. December 5, 2011. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (November 8, 2001). "Hollywood's Score Keeper". elmerbernstein.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Johnston, Alex (April 19, 2016). "Six great moments of classical music in film". The List. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (May 16, 1983). "Hollywood Forecast: Best Summer At Box Office". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Maslin, Janet (June 8, 1983). "Akyroyd In 'Trading Places'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ a b "Trading Places (1983)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Weekend Domestic Chart for June 10, 1983". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Weekend Domestic Chart for June 17, 1983". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Weekend Domestic Chart for June 24, 1983". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Trading Places (1983)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "'Jedi' Leads Record-setting Summer Film Season". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 11, 1983. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "Top 1983 Movies at the Domestic Box Office". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Trading Places (1983)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Rental champs: Rate of return". Variety. December 15, 1997. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Variety 1995, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Canby, Vincent (June 19, 1983). "Film View; 'trading Places' Brings 30's Comedy Into The 80's". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ebert, Roger (June 8, 1983). "Trading Places". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Arnold, Gary (June 8, 1983). "The Ups &". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Kehr, Dave (1983). "Trading Places". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Picks and Pans Review: Trading Places". People. June 27, 1983. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Kempley, Rita (June 10, 1983). "'Trading Places': Right On The Money". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "The 41st Annual Golden Globe Awards (1984)". GoldenGlobes.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 56th Academy Awards". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ "Film Nominations 1983". Bafta.org. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c Canby, Vincent (September 18, 1983). "Film View; At The Box Office, Summer Has A Split Personality". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Johns, Lindsay (November 30, 2013). "Trading Places at 30 – one of the funniest films of all time". The Spectator. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (October 10, 1983). "Movies For '84 Will Try To Copy Successes Of '83". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Grenier, Richard (March 10, 1985). "Eddie Murphy's Comic Touch". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 28, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (April 30, 1984). "Eddie Murphy As Pop Singer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (June 25, 1983). "Film Studios Wonder If New Hits Will Last". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Blume, Lesley M. M. (June 4, 2014). "The Making of Ghostbusters: How Dan Aykroyd, Harold Ramis, and "The Murricane" Built "The Perfect Comedy"". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- ^ "Dan Aykroyd Biography". Fandango. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Dan Aykroyd Filmography". Fandango. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Haflidason, Almar (2003). "A Fish Called Wanda Special Edition DVD (1988)". BBC Online. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Zehme, Bill (August 24, 1989). "Eddie Murphy: Call Him Money". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Green, Marc; Farber, Stephen (August 28, 1988). "Trapped in the Twilight Zone : A Year After the Trial, Six Years After the Tragedy, the Participants Have Been Touched in Surprisingly Different Ways. And the Hollywood Controversy Still Burns". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "15 moments that define the career of Eddie Murphy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Harmetz, Aljean (May 17, 1984). "Hollywood Thriving On Video-cassette Boom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ "In Brief: Recent Films On Cassettes". The New York Times. May 27, 1984. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Hajdu, David (January 8, 1984). "Film View; After A Slow Beginning, A Rousing Conclusion". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Horn, Steven (October 2, 2002). "Trading Places". IGN. Archived from the original on October 27, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ McCutcheon, David (March 13, 2007). "Places Trading New DVD". IGN. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Miller III, Randy (June 1, 2007). "Trading Places: Looking Good, Feeling Good Edition". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (June 13, 2007). "Trading Places / Coming To America". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Prange, Stephanie (April 3, 2018). "Paramount Celebrates Anniversaries of Eddie Murphy's 'Trading Places' and 'Coming to America' June 12 on Blu-ray". Media Play News. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Trading Places: Limited Edition". LaLaLandRecords.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Wile, Rob (July 1, 2013). "Here's What Happened In The Complex Commodity Trade At The End Of 'Trading Places'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith, Robert (July 12, 2013). "What Actually Happens At The End Of 'Trading Places'?". NPR. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ Berry, Richard James (May 1, 2018). "Why The Dukes Went Bust At The End Of Trading Places And Why It's Relevant Today". HuffPost. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c Budd 2002, p. 210.

- ^ a b Childs 2006, p. 44.

- ^ "The Prince and the Pauper". penguinrandomhouse.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Monahan, Mark (May 20, 2005). "Dan Aykroyd Biography". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ Anderson 1990, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Schiff, Stephen (August 26, 1984). "Lights! Camera! Election!". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c Reid, Pad (January 1, 2000). "Empire Essay: Trading Places Review". Empire. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Vera & Gordon 2003, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Freeman, Hadley (April 8, 2014). "My guilty pleasure: Trading Places". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Karlen, Neal (July 18, 1985). "Jamie Lee Curtis Gets Serious". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Metcalf 1991, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b Patrick, Seb (December 19, 2008). "My favourite Christmas film: Trading Places". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "150 Essential Comedy Movies To Watch Now". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 30, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 50 Greatest Comedies". Empire. July 31, 2019. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Comedies of all Time". BBC. August 22, 2017. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Writers Choose 101 Funniest Screenplays". WGA.org. November 11, 2015. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ Rivenbark Rich, Celia (September 16, 1988). "Dan Aykroyd Shooting for 'A' List Movie". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Polowy, Kevin (September 14, 2016). "Eddie Murphy Chooses 'Coming to America' Over 'Trading Places'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Crow, David (March 5, 2021). "Coming 2 America Is A Sequel To More Than One Eddie Murphy Movie". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Guerrasio, Jason (March 6, 2021). "How 'Coming 2 America' Paid Homage To Another Classic Eddie Murphy Movie". Insider.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Matt (March 4, 2010). "First the Volcker Rule, Now the Eddie Murphy Rule!". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Film Royalties: Classic Comedy "Trading Places"". Royalty Exchange. 2019. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Arends, Brett (February 12, 2019). "Looking good, Billy Ray! Rights to 'Trading Places' go up for sale". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Rizzo, Frank (June 7, 2022). "Trading Places Review: Modern Touches Brighten Uneven Adaptation Of Reagan-Era Movie Comedy". Variety. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Stockdale, Charles (December 15, 2019). "The 75 best movie comedies of the '80s". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "140 Essential '80s Movies". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 55 Best Christmas Movies Of All Time". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 17, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "101 Funniest Screenplays List". WGA.org. November 11, 2015. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ Schuster, Mike. "The 11 Best Movie Comedies of the '80s". IFC. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Evry, Max (March 2, 2011). "The 25 Most Essential '80s Comedies". MTV.com. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave; Clarke, Cath; de Semlyen, Phil; Kheraj, Alim; Huddleston, Tom; Johnston, Trevor; Jenkins, David; Lloyd, Kate; Seymour, Tom; Smith, Anna; Walters, Ben; Davies, Adam Lee; Harrison, Phil; Adams, Derek; Hammond, Wally; Lawrenson, Edward; Tate, Gabriel (March 23, 2020). "The 100 best comedy movies: the funniest films of all time". Time Out. Archived from the original on April 17, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Holiday 5: The Most Underrated Christmas Flicks". The Washington Post. December 17, 2008. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ O'Hara, Helen (December 22, 2016). "The 30 Best Christmas Movies". Empire. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (November 13, 2018). "These are the top 20 Christmas movies ever". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Jackson, Dan; Patches, Matt (November 26, 2019). "The 50 Best Christmas Movies of All Time". Thrillist. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "The 50 best Christmas movies". Time Out. October 22, 2019. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Here are the 75 best Christmas movies of all time for the holidays". Today. November 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 10, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Murtaugh, Taysha (December 24, 2019). "70 Best Christmas Movies to Binge-Watch This Holiday Season". Country Living. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "The 25 best Christmas movies, from Love Actually to The Muppets Christmas Carol". The Daily Telegraph. December 24, 2019. Archived from the original on December 26, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Beretta, Alessandro (December 24, 2018). "Perché a ogni vigilia di Natale c'è "Una poltrona per due" su Italia 1". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Trading Places (1983)". Rotten Tomatoes. September 24, 2002. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ "Trading Places". Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Waxman, Sharon (July 3, 2004). "Using a Racial Epithet To Combat Racism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Tong, Alfred (June 12, 2020). "Dan Aykroyd's Trading Places watch is worth much more than $50". GQ. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Ravindran, Manori (June 21, 2020). "Sky Adds 'Outdated Attitudes' Disclaimer for 'Jungle Book,' 'Breakfast at Tiffany's'". Variety. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

Works cited

[edit]- Anderson, Carolyn (1990). "Diminishing Degree of Separation". In Loukides, Paul; Fuller (eds.). Beyond the Stars: Themes and ideologies in American popular film. Bowling Green University Popular Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-87972-701-7. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Budd, David (2002). "Classic Encounters of Black on White". Culture Meets Culture in the Movies: an Analysis East, West, North, and South, With Filmographies. McFarland & Company. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-7864-1095-8. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- Childs, Peter (2006). "Pop Video". Texts: Contemporary Cultural Texts and Critical Approaches. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2043-2. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Metcalf, Greg (1991). "Christmas Conventions of American Films in the 1980s". In Loukides, Paul; Fuller, Linda K. (eds.). Beyond the Stars: Plot conventions in American popular film. Bowling Green University Popular Press. pp. 100–113. ISBN 978-0-87972-517-4. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- "UIP's $25M-Plus Club (to end '94)". Variety. September 11, 1995.

- Vera, Hernan; Gordon, Andrew (2003). "8: White Out: Racial Masquerade by Whites in American Film I". Screen Saviors: Hollywood Fictions of Whiteness. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9946-9. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

External links

[edit]- 1983 films

- 1980s satirical films

- American business films

- American Christmas films

- American satirical films

- American screwball comedy films

- Blackface minstrel shows and films

- 1980s Christmas comedy films

- Coming to America (film series)

- Economics films

- Fictional portrayals of the Philadelphia Police Department

- Films directed by John Landis

- Films scored by Elmer Bernstein

- Films set in New York City

- Films set around New Year

- Films set in Philadelphia

- Films shot in Philadelphia

- Films shot in the United States Virgin Islands

- Films with screenplays by Herschel Weingrod

- Films with screenplays by Timothy Harris (writer)

- Paramount Pictures films

- Stock trading films

- Wall Street films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films

- 1983 comedy films

- English-language Christmas comedy films