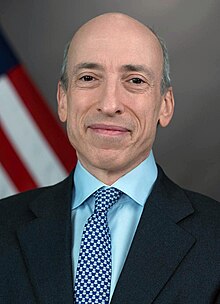

Gary Gensler

Gary Gensler | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2022 | |

| 33rd Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission | |

| Assumed office April 17, 2021 | |

| President | Joe Biden |

| Preceded by | Allison Lee (Acting) |

| Commissioner of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission | |

| Assumed office April 17, 2021 | |

| President | Joe Biden |

| Preceded by | Jay Clayton |

| 11th Chair of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission | |

| In office May 26, 2009 – January 3, 2014 | |

| President | Barack Obama |

| Preceded by | Reuben Jeffery III |

| Succeeded by | Timothy Massad |

| Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance | |

| In office April 1999 – January 20, 2001 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | John Hawke |

| Succeeded by | Peter Fisher |

| Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Financial Markets | |

| In office September 1997 – April 1999 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Darcy Bradbury |

| Succeeded by | Lee Sachs |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 18, 1957 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | University of Pennsylvania (BS, MBA) |

Gary S. Gensler (born October 18, 1957) is an American government official and former investment banker served as the chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).[1] Gensler previously worked for Goldman Sachs and has led the Biden–Harris transition's Federal Reserve, Banking, and Securities Regulators agency review team.[2] Prior to his appointment, he was professor of Practice of Global Economics and Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management.[3]

Gensler served as the 11th chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, under President Barack Obama, from May 26, 2009, to January 3, 2014. He was the Under Secretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance (1999–2001), and the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Financial Markets (1997–1999). Prior to his career in the federal government, Gensler worked at Goldman Sachs, where he was a partner and co-head of finance. Gensler also served as the CFO for the Hillary Clinton 2016 presidential campaign.[4] President Joe Biden nominated Gensler to serve as 33rd chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.[5] He succeeded SEC Acting Chair Allison Lee.

Early life and education

[edit]Gensler was born into a Jewish family[6] in Baltimore, Maryland, one of five children of Jane (née Tilles) and Sam Gensler.[7] Sam Gensler was a cigarette and pinball machine vendor to local bars,[8] and he provided Gensler with his first exposure to the real-world side of finance when Sam would take Gensler to the bars of Baltimore to count nickels from the vending machines.[6]

Gensler graduated from Pikesville High School in 1975,[9] where he was later given a Distinguished Alumnus award.[10] Gensler graduated with a degree in economics, summa cum laude, after three years at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania,[11] followed by a master's in business administration the following year.[9] Gensler's identical twin brother also studied at the University of Pennsylvania.[12] As an undergraduate, Gensler joined the University of Pennsylvania crew as a coxswain, dropping his weight to 112 pounds to keep the boat at its proper weight.[9]

Business career

[edit]In 1979, Gensler joined Goldman Sachs, where he spent 18 years.[13] At 30, Gensler became one of the youngest persons to have made partner at the firm at the time.[14] He spent the 1980s working as a top mergers and acquisitions banker, having assumed responsibility for Goldman's efforts in advising media companies.[15] He subsequently made the transition to trading and finance[16] in Tokyo,[8] where he directed the firm's fixed income and currency trading.[15]

While at Goldman Sachs, Gensler led a team that advised the National Football League in capturing the then-most lucrative deal in television history, when the NFL secured a $3.6 billion deal selling television sports rights.[17]

Gensler's last role at Goldman Sachs was co-head of finance, responsible for controllers and treasury worldwide.[18] Gensler left Goldman after 18 years[19] when he was nominated by President Bill Clinton and confirmed by the U.S. Senate to be the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury.[11]

Gensler served on the board of for-profit university Strayer Education, Inc. from 2001 to 2009.[20]

Public service

[edit]

Treasury Department

[edit]Gensler served in the United States Department of the Treasury as Assistant Secretary for Financial Markets from 1997 to 1999, then as Undersecretary for Domestic Finance from 1999 to 2001. As Assistant Secretary, Gensler served as a senior advisor to the Secretary of the Treasury in developing and implementing the federal government's policies for debt management and the sale of U.S. government securities.[15] In 1999 and 2000, under then-Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, Gensler fought for passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which exempted over-the-counter derivatives from regulation.[21]

As Undersecretary of the Treasury for Domestic Finance, Gensler advised and assisted Treasury Secretaries Robert Rubin and Lawrence Summers on aspects of domestic finance, including formulating policy and legislation in the areas of financial institutions, public debt management, capital markets, government financial management services, federal lending, fiscal affairs, government sponsored enterprises, and community development.[15]

While serving at the Treasury Department, Gensler was awarded the agency's highest honor, the Alexander Hamilton Award, for his service.[11]

Sarbanes-Oxley

[edit]In 2001, Gensler joined the staff of U.S. Senator Paul Sarbanes, chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, as a senior advisor and helped write the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which tightened accounting standards in the wake of the Enron and WorldCom scandals.[14]

CFTC

[edit]Then-President-elect Barack Obama announced his intent to nominate Gensler to serve as the 11th chairman of the CFTC on December 18, 2008.[18] His nomination was officially sent to the U.S. Senate on January 20, 2009.[22] After some initial opposition to Gensler's nomination amongst the progressive members of the Democratic caucus, Gensler was approved by the U.S. Senate in an 88–6 confirmation vote.[14][23] Gensler was sworn in on May 26, 2009, pledging to work to "urgently close the gaps in our laws to bring much-needed transparency and regulation to the over-the-counter derivatives market to lower risks, strengthen market integrity and protect investors".[24]

Gensler was described as "one of the leading reformers after the financial crisis".[8]

Swaps

[edit]During Gensler's tenure at the CFTC, he worked closely with the Obama Administration, United States Congress and other regulators to transform the $400 trillion financial derivatives markets that were at the center of the 2008 financial crisis.[25] Upon becoming chairman, Gensler began leading the Obama Administration's effort "to start policing the Wild West of finance: the murky market for over-the-counter derivatives".[14] When the Treasury Department released draft legislation to bring regulatory oversight to the swaps market, Gensler sent a letter to Congress arguing that the proposal did not go far enough.[26]

By the spring of 2010, the momentum in Congress was toward Gensler's vision for derivatives oversight,[13] and Congress passed comprehensive reform as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in July 2010.

After the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, Gensler led the CFTC's effort to write the rules required to regulate the swaps markets.[27] He oversaw the agency as it wrote 68 new rules, orders and guidances[28] and as its reach extended from a $35 trillion futures market to a $400 trillion swaps market.[8] Under Gensler, the bipartisan commission reached unanimous votes to approve more than 70 percent of the agency's rulemakings.[8] By the time Gensler left the CFTC in January 2014, the agency was near completion of the rule-writing process to implement the Dodd-Frank Act.[29]

Enforcement and Libor investigation

[edit]Gensler led a revitalization of the enforcement division of the agency, most notably in its prosecution of an enforcement case regarding manipulation of Libor, the London interbank offered rate.[30]

Early in his tenure, Gensler listened to tape recordings of two Barclays employees as they discussed plans to report false interest rates in an effort to manipulate Libor.[30] Libor is the average interest rate estimated by leading banks in London that the average leading bank would be charged if borrowing from other banks.[31] It is used as a reference rate for many financial products, including adjustable rate mortgages, student loans, and car payments.[6]

"A driving force behind the latest crackdown tied to LIBOR",[6] Gensler worked with enforcement division director David Meister and his team to lead the investigative effort and brought charges against five financial institutions for the manipulation of Libor and other benchmark interest rates, resulting in more than $1.7 billion in penalties.[11] Barclays alone paid $450 million in fines as a result of the Libor investigation.[6] Gensler has called Libor "unsustainable" and argued that it should be replaced as a benchmark rate.[32]

MF Global

[edit]Gensler was Chair of the CFTC during the collapse of MF Global.[33][34]

Gensler recused himself from the case, because of his previous relationship with MF Global's Chairman and CEO, Jon Corzine.[35][36]

Frankel Fiduciary Prize

[edit]For his work to reform the financial regulatory system, The Institute for the Fiduciary Standard awarded Gensler with the 2014 Tamar Frankel Fiduciary Prize.[37]

Maryland Financial Consumer Protection Commission

[edit]In 2017, Gensler was selected by the Maryland Senate President and House Speaker to serve as Chairman of the Maryland Financial Consumer Protection Commission, which assessed the impact of potential changes to federal financial industry laws, regulations, budgets, and policies on the state.[38] Under Gensler's leadership, the Commission recommended changes to State law to enhance consumer financial protections, including enhancing standards of care, clarifying State law to set standards for student loan servicers, and protecting Maryland buyers of manufactured homes. In 2018, student loan legislation recommended by the Commission established a student loan ombudsman,[39] added the federal Military Lending Act and the federal Servicemembers Civil Relief Act to state law, increased civil monetary penalties for violations, and codified some modifications on debt collection laws.[40] In 2019, the state enacted additional Commission-recommended legislation to create a Student Borrower Bill of Rights to protect students from predatory practices.[41]

SEC

[edit]In November 2020, Gensler was named a volunteer member of the Joe Biden presidential transition Agency Review Team to support transition efforts related to the Federal Reserve, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, and the Securities and Exchange Commission.[42] On March 11, 2021, his nomination was reported out of the Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Development Committee by a vote of 14–10.[43] On April 14, 2021, his nomination was confirmed in the Senate by a vote of 53–45 to fill former chair Jay Clayton's term expiring in June 2021.[44] On April 19, 2021, the Senate confirmed Gensler to a 5-year term through 2026 by a vote of 54–45.[45]

Cryptocurrency

[edit]On September 14, 2021, Gensler testified before the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee that the SEC was in need of large staffing increases to address regulatory concerns related to cryptocurrencies and other digital assets,[46][47] and Gensler likened the cryptocurrency market to a "Wild West".[48][49] On September 21, Gensler remarked to The Washington Post that most cryptocurrency projects dealing with securities should fall under the regulatory purview of the SEC, though the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), of which he was a former chair, was better suited for some others.[50] On October 5, Gensler testified before the U.S. House Financial Services Committee that the SEC had no plans to ban cryptocurrencies.[51][52] On October 15, the SEC approved the first bitcoin futures exchange-traded fund (ETF) in the United States after Gensler announced support for doing so the previous August.[53][54][55] Gensler is opposed to approving pure play bitcoin ETFs due to bitcoin remaining subject to fraud and market manipulation.[56]

After a period of high anticipation and speculation from financial news outlets and markets about the SEC approval of a spot bitcoin ETF, at 4:11pm ET on January 9, 2024, a post was published to the SEC's X account announcing the approval of spot bitcoin ETFs. By 4:26 pm, SEC chair Gary Gensler had issued a retraction and said the agency's account had been "compromised," and that an "unauthorized tweet was posted." In the minutes after the fake post was published, the price of bitcoin jumped around 2.5% and led to an overall $40 billion swing in the combined value of bitcoin in circulation.

The Economist identified the risks presented by decentralized finance and crypto-assets valued at $2.5 trillion as a challenge for Gensler in 2022, and noted his experience in teaching blockchain technology.[57] On April 4, 2022, Gensler announced that the SEC would begin to register and regulate cryptocurrency exchanges at a University of Pennsylvania Law School students association conference.[58] On May 11, Gensler stated in an interview with Bloomberg News that cryptocurrency exchanges were market making against the interests of their customers after warning the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government that cryptocurrency exchanges were engaged in front running the previous May.[59][60][61] Following testimony before the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government on May 18, Gensler warned in a post-hearing press conference that many cryptocurrencies were going to fail and expressed concern that it could undermine confidence in the traditional financial markets.[62]

On June 7, U.S. Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D–NY) and Cynthia Lummis (R–WY) introduced a bill in the 117th U.S. Congress to create a regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies that would treat most digital assets as commodities subject to oversight from the CFTC and would not have cryptocurrencies subject to oversight from the SEC unless a cryptocurrency's holders were entitled to the same privileges as corporate investors.[63] At a conference hosted by The Wall Street Journal on June 14, Gensler expressed concern that the Lummis-Gillibrand bill could inadvertently undermine stock market and mutual fund protections, noted that cryptocurrency companies were already engaging in behaviors overseen by the SEC, and argued that some digital assets are securities necessitating oversight from the SEC rather than commodities (even if the overwhelming majority of tokens offered by cryptocurrency exchanges are commodities).[64] On January 12, 2023, the SEC filed a complaint in Southern New York U.S. District Court that both Genesis and Gemini of offering and selling unregistered securities.[65]

Financial regulation

[edit]On May 6, 2021, Gensler testified before the U.S. House Financial Services Committee about the GameStop short squeeze, Robinhood Markets, Archegos Capital Management, market concentration among market makers for payment for order flow, conflict of interest in best execution for trades with PFOF, trading gamification in mobile trading apps and high-frequency trading, the SEC consolidated audit trail, data security, usage of social media and the internet in market manipulation, and ESG disclosure rules (including those proposed by the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures led by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg).[list 1][cleanup needed]

On May 25, U.S. Senators Elizabeth Warren (D–MA) and Bernie Sanders (I–VT) sent a letter to Gensler urging the SEC to remove and replace the sitting members of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), arguing that Trump Administration appointees had politicized the agency and compromised its independence.[70]

On June 4, the SEC voted to remove William Duhnke as PCAOB Chair and began an investigation on June 17 of his handling of internal complaints while serving as PCAOB Chair.[71][72][73] On June 9, Gensler announced that the SEC would review market structure following the GameStop short squeeze and the AMC Entertainment Holding, Inc. meme stock short squeeze,[74] and Gensler signaled in an interview with Barron's the following August that a complete ban on payment for order flow was being considered by the review.[75] Speaking at The Wall Street Journal CFO Network event on June 7, Gensler emphasized the need for new restrictions and rules to reduce the risk of improper insider trading.[76] On June 30, Robinhood Markets agreed to pay $70 million to settle a lawsuit filed by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) that alleged that the company had misled its customers, approved ineligible and inexperienced traders for options strategies, and did not supervise its technology properly to prevent outages.[77]

On July 29, Robinhood Markets launched an IPO for its stock on the Nasdaq.[78][79] On August 6, the SEC approved new rules implemented by Nasdaq, Inc. requiring that companies listed on its exchanges to include at least one female member on their boards of directors and at least one racial minority or LGBTQ board member and to require disclosure of statistics measuring the diversity of their board membership.[80] On August 27, the SEC launched a review of strategies and practices used by online brokers and investment advisors that promote user engagement with trading gamification.[81] On December 2, the SEC finalized a rule to implement the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act.[82] In response to record stock sales by CEOs and other corporate executives that year,[83] Gensler proposed an agency rule for a mandatory 120-day window for corporate executives who are changing existing or adopting new portfolio managements plans on December 15.[84]

On January 27, 2022, Southern Florida U.S. District Court Judge Cecilia Altonaga dismissed a lawsuit filed by investors against Robinhood Markets for acting negligently during the GameStop short squeeze.[85] On February 11, the SEC met to discuss more than 50 proposed rules changes (focused primarily on hedge funds and private equity) including a requirement that the disclosure documents of stock corporations must include a written statement of company cybersecurity risk management policies and disclosure of any cyberattacks.[56] On May 18, Gensler testified before the U.S. House Appropriations Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government requesting an even greater increase to its appropriation in the 2023 U.S. federal budget than the 8 percent increase proposed by President Biden.[86][87]

On June 8, Gensler announced rules changes to require that market makers disclose more data about payments for order flow (PFOF) and the timing for the best execution of trades, as well as to require direct competition among stockbrokers executing trades for retail investors at a conference hosted by Piper Sandler Companies.[88][89] On May 12, FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried disclosed a Schedule 13D filing with the SEC to buy a 7.6 percent ownership stake in Robinhood Markets.[90][91] On June 27, FTX CEO Sam Bankman-Fried stated that no mergers and acquisitions discussions were being held with Robinhood Markets about an acquisition (despite reports of internal discussion to do so and reports of the company approaching at least three stock trading start-ups about acquisitions).[list 2] On July 20, the Social Science Research Network released a preprint written by economists Maureen O'Hara, Robert P. Bartlett, and Justin McCrary that suggested that Robinhood Markets traders caused a surge in trading volume of Berkshire Hathaway Class A shares in February and March 2021.[97][98][99]

Greenwashing, ESG, and carbon neutrality

[edit]On January 28, 2021, Microsoft disclosed an investment in Climeworks, a direct air capture company,[100][101][102] one year after the company announced a strategy to take the company carbon negative by 2030 and to remove all the carbon from the environment the company has emitted since 1975 by 2050.[103][104][105] In 2021 and 2022, an index constructed by researchers at the University of Cambridge showed that bitcoin mining consumed more electricity during the course of the year than the entire nations of Argentina (a G20 country) and the Netherlands.[106][107][108] On February 8, 2021, Tesla, Inc. disclosed to the SEC that it purchased $1.5 billion worth of bitcoin.[109] On April 15, Apple Inc. announced the creation of $200 million forestry fund as part of the company's strategy to become carbon neutral by 2030.[110]

On February 7, 2022, the NewClimate Institute, a German environmental policy think tank, published a survey evaluating the transparency and progress of the climate strategies and pledges announced by 25 major companies in the United States that found that the climate pledges of Alphabet, Amazon, and Apple were unsubstantiated and misleading.[111][112] On June 23, 2020, Amazon.com, Inc. announced a $2 billion venture fund to invest in startup companies developing strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as part of a strategy to be climate neutral company by 2040,[113] after announcing a $10 million investment to two projects in the Appalachian Mountains the previous April to manage their lands to maximize greater carbon removal, the first investment from a $100 million initiative to support reforestation and habitat restoration.[114] On June 30, 2021, Amazon released its annual company annual sustainability report that showed that company net carbon emissions grew by 19 percent from 2019 to 2020.[115]

On February 11, 2022, Western Louisiana U.S. District Court Judge James D. Cain Jr. issued a preliminary injunction in Louisiana v. Biden (2022) in favor of the plaintiffs to block federal agency requirements to assess the societal costs of greenhouse gas emissions in regulatory actions under Executive Order 13990.[116] On March 16, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals stayed the decision following an appeal by the U.S. Justice Department,[117] and on May 26, the U.S. Supreme Court issued an order without comment or opposition dismissing an appeal filed by the plaintiffs to reverse the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals decision.[118][119][120] On February 15, ConocoPhillips announced a pilot program to sell its flare gas to a company operating a bitcoin mine in the Bakken Formation region of North Dakota as part of an industry initiative to reduce routine flaring to zero by 2030.[121] On March 21, the SEC approved rules requiring the disclosure of stock corporation climate risks and net contribution to greenhouse gas emissions in 10-K forms.[122][123] On the same day, The Wall Street Journal criticized Gensler for proposing legislation requiring public companies to disclose climate risks. "The proposal ... is contrary to SEC history, securities law, and sound regulatory practice", the paper wrote. It accused the SEC chairman of trying "to regulate private companies by the back door" and following the bidding of BlackRock and other investors.[124]

On March 26, CNBC reported that ExxonMobil started a pilot program in January 2021 with Crusoe Energy Systems to also divert its flare gas into generators producing electricity to power shipping containers full of bitcoin miners in the North Dakota Bakken region (which it expanded the following July) as part of the same industry initiative with ConocoPhillips, and that Crusoe has stated reduces carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 63 percent as compared with continued flaring.[125] On April 12, Alphabet Inc., Meta Platforms, Shopify, McKinsey & Company, and Stripe, Inc. announced a $925 million advance market commitment of permanent carbon removal from companies that are developing the technology over the next 9 years.[126][127] On May 19, after Tesla was removed from the S&P 500 ESG Index by S&P Dow Jones Indices, Tesla CEO Elon Musk posted a tweet to his Twitter account criticizing the decision and, in noting that ExxonMobil was rated within the top 10 constituent companies in the index by weight, accused ESG of being a scam.[128][129]

On May 25, the SEC proposed two rules changes to ESG investment fund qualifications to prevent greenwashing marketing practices and to increase disclosure requirements for achieving ESG impacts.[130] On June 10, the SEC was reportedly investigating the ESG investment funds of Goldman Sachs for potential greenwashing.[131] After noting that his company had launched a division to commercialize carbon capture in testimony before the U.S. House Oversight and Reform Committee on October 28, 2021,[132][133] ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods discussed in an interview with CNBC journalist David Faber on June 24 that part of ExxonMobil's long-term strategy to remain a profitable company while reducing greenhouse gas emissions and plastic pollution was to invest in carbon capture and storage technology with a network hub in Houston and to remain a plastics producer while making improvements to waste management.[134][135][136] On June 30, the Supreme Court ruled in West Virginia v. EPA (2022) that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency did not have the authority under the Clean Air Act to devise a broad cap-and-trade system for carbon emissions by power plants that the agency attempted to promulgate under the Clean Power Plan and instead that the authority to do so rests with the U.S. Congress.[137][138][139]

Social media

[edit]On March 2, 2021, Rocket Mortgage saw a more than 70 percent spike in its stock price during the GameStop short squeeze due to a surge in trading following discussion of the company on r/wallstreetbets,[140][141] but the Rocket Mortgage stock price reverted to its pre-surge level the next day.[142][143] On September 14, Gensler announced the imminent release of an agency report on the short squeeze in testimony before the U.S. Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee.[144][145][49] On October 18, the SEC released the report.[146][147][148] Also in October 2021, eight whistleblower complaints alleging securities fraud by Facebook, Inc. were filed anonymously with the SEC by Whistleblower Aid on behalf of former company employee Frances Haugen after Haugen leaked thousands of company documents to The Wall Street Journal the previous month.[149][150][151] After publicly revealing her identity on 60 Minutes,[152][153] Haugen testified before the U.S. Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, Product Safety, and Data Security about the content of the leaked documents and the complaints.[154][155] After the company renamed itself as Meta Platforms,[156] Whistleblower Aid filed two additional securities fraud complaints with the SEC against the company on behalf of Haugen in February 2022.[157]

On November 18, 2021, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D–MA) sent a letter to Gensler requesting that the SEC investigate possible securities law violations in the conduct of a merger between the Digital World Acquisition Corp. (DWAC), a special-purpose acquisition company, and the Trump Media & Technology Group (TMTG) announced on October 20.[list 3] On December 6, an ongoing SEC investigation into the DWAC–TMTG merger was disclosed by DWAC in a filing with the agency.[162] On February 18, 2022, the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in a lawsuit against Bitconnect that the Securities Act of 1933 extends to targeted solicitation using social media.[163] In a securities filing dated June 8 and disclosed to the Florida State Department Corporations Division, DWAC stated that Donald Trump and Donald Trump Jr. had been removed from the company board of directors.[164][165] On June 14, DWAC disclosed that the SEC issued a subpoena for additional company documents and information about the merger.[166] On June 27, DWAC disclosed that the SEC issued an additional subpoena as well as an investigation by the U.S. Justice Department.[167][168] On July 19, Amazon. filed a lawsuit against more than 10,000 Facebook group administrators for distributing fake user reviews of Amazon products in violation of Facebook company policies.[169][170]

Tesla and Twitter

[edit]On November 6, 2021, Tesla, Inc. CEO Elon Musk posted a tweet on his Twitter account that conducted a poll of his followers over whether he should sell 10% of his Tesla stock.[171] On December 3, Musk had sold approximately $10 billion worth of his Tesla shares.[172][173] On December 6, the SEC opened an investigation of Tesla in response to a whistleblower complaint alleging the company did not properly disclose to its shareholders fire risks associated with its solar panels.[174] On February 7, 2022, Tesla disclosed in a filing to the SEC that the agency had issued a subpoena to the company for information about company governance policies to comply with an October 2018 settlement with the agency in a securities fraud lawsuit over a tweet Musk posted on his Twitter account about taking Tesla private in August 2018 that the agency subsequently requested that Musk be held in contempt of court for violating in February 2019 (that resulted in an amended settlement the following April),[list 4] and that the agency sent letters to the company in 2019 and in 2020 warning the company that tweets Musk posted in July 2019 and in May 2020 were in violation of.[list 5]

On February 17, Musk's attorneys filed a letter with the presiding judge in the 2018 settlement alleging that the SEC was attempting to chill his First Amendment right to freedom of speech and that the SEC had failed to pay Tesla shareholders the $40 million in fines the agency had assessed from him and the company under the terms of the settlement,[188][189] which the SEC disputed in a letter filed with the court in response on February 18.[190][191] On February 21, Musk's attorneys filed a second letter with the court alleging the SEC had illegally leaked information from an investigation into him.[192][193] On February 24, Southern New York U.S. District Court Judge Alison Nathan issued an order rejecting requests made by Musk in his February 21 letter,[194] while the SEC was in the process of conducting an insider trading investigation of Musk and his brother Kimbal Musk for a $108 million sale of Tesla stock before Elon's November 2021 tweet.[195][196]

On March 8, Musk filed a motion with the court to have the 2018 settlement with the SEC terminated.[197][198] On March 22, the SEC filed a response to Musk's March 8 filing requesting that Judge Nathan deny Musk's motion, that its subpoenas were lawful, and disclosed that the agency was investigating Musk for his November 2021 tweet.[199] On March 29, Musk filed another letter with the court reiterating his First Amendment concerns.[200][201] On April 4, Musk submitted a 13G filing with the SEC to purchase a 9.2% passive ownership stake in Twitter, Inc.,[202][203] but then submitted a Schedule 13D beneficial ownership filing reserving the right to purchase a larger stake in the company with the agency the next day (and because the disclosure was filed later than an SEC deadline, it may have made Musk an additional $156 million).[204][205][206] On April 13, a group of Twitter shareholders filed a lawsuit against Musk for failing to disclose his ownership stake to the SEC within the agency's prescribed deadline.[207] On April 14, Musk filed an offer to buy Twitter, Inc. with the SEC for $43 billion and take the company private (which was revised a week later to $46.5 billion).[208][209]

On April 15, Northern California U.S. District Court Judge Edward M. Chen ruled in a lawsuit filed by Tesla shareholders against Musk and the company that his August 2018 tweet was a knowingly made false statement of fact (the day after Musk stated at the 2022 TED conference that it was not).[210][211] On April 22, Republican Conference members of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee wrote a letter to the Twitter board of directors requesting that company executives preserve all company records related to Musk's acquisition proposal.[212] On April 25, the Twitter board of directors unanimously agreed to Musk's acquisition proposal at $44 billion.[213][214] On April 27, Southern New York U.S. District Court Judge Lewis J. Liman denied Musk's motion to terminate the 2018 settlement.[215][216] On April 30, Musk filed an amicus brief along with Dallas Mavericks team owner Mark Cuban in support of a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court by a former chief financial officer at Xerox to review a 2003 settlement the Xerox CFO made with the SEC that includes a gag order that the plaintiff argues is in violation of his First Amendment right to freedom of speech.[217]

On May 13, Musk posted a tweet that his acquisition of Twitter would be put on hold until statistics about spambots and fake accounts on Twitter were verified,[218][219] while the SEC and the Federal Trade Commission began investigations of Musk for violating filing deadlines for his Twitter passive ownership stake and his subsequent company acquisition proposal respectively.[220] On May 16, Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal posted a tweet detailing company policies for addressing fake and spam accounts in response to Musk (to which Musk posted a tweet in return).[221] On May 17, Musk tweeted that the Twitter acquisition would not move forward until he had greater clarification about the ratio of fake and spam accounts on the site,[222] later tweeting a poll of his followers' opinions of Twitter, Inc. statements about the ratio of fake and spam accounts in filings to the SEC (and where Musk posted a comment in the poll thread calling upon the SEC to investigate whether the company's statements disclosing the ratio in filings to the agency are true).[223][224]

On the same day, Twitter submitted a new filing with the SEC that stated that Musk had met with Twitter executives for three days before he announced his acquisition proposal.[225][226] On May 24, Reuters reported that since the April 2019 amended settlement between Musk and the SEC, agency officials have consciously chosen not to pursue legal action against Musk for violating the terms of the agreement and to write letters urging compliance instead due to remarks made by the presiding judge during the case.[227] On May 25, Twitter shareholders filed a class action lawsuit against Musk and Twitter, Inc. alleging market manipulation and violation of California corporate laws.[228] On June 3, a dozen political advocacy groups (including the Center for Countering Digital Hate, GLAAD, and MediaJustice) announced a campaign to block Musk's Twitter acquisition proposal by pressuring government agencies to review the acquisition, persuading Tesla shareholders to take legal action against the proposal, and asking advertisers to boycott the platform.[229]

On June 6, Musk's attorneys disclosed a letter to the SEC accusing Twitter executives of a material breach of contract due to lack of information provided about fake and spam accounts and claimed to reserve Musk's right to terminate the merger agreement (despite Musk waiving due diligence in his offer to buy the company on April 14).[230][231] On July 1, an investment management group affiliated with the pension funds of Strategic Organizing Center labor unions wrote a letter to the SEC requesting that the agency investigate Tesla for violating the terms of the October 2018 settlement with the agency after the company disclosed in its annual proxy statement (filed with the SEC the previous month) that Oracle Corporation CEO Larry Ellison did not intend to stand for re-election as company chairman and that the company did not intend to replace his seat on the board (thereby reducing its size).[232][233]

On July 8, Musk filed a letter with the SEC sent to Twitter executives notifying them that he intended to terminate his acquisition proposal of the company, to which Twitter Board Chairman Bret Taylor posted a tweet stating that the company would continue to attempt to close the transaction and that it would pursue legal action to enforce the merger.[234][235] On July 12, Twitter Inc. filed a lawsuit against Musk in the Delaware Court of Chancery to enforce the acquisition agreement.[236] On July 14, the SEC disclosed a letter sent to Musk on June 2 for additional information about his 13D filing on April 5.[237][238] On July 15, Musk filed a motion requesting that the court not grant Twitter's request for a speedy trial,[239][240] while Twitter submitted an amended proxy statement with the SEC that urged company shareholders to approve the acquisition agreement.[241]

On July 18, Twitter submitted a filing with the court stating that Musk's request to deny a speedy trial was a tactical delay, that Musk's tactics were harming Twitter's reputation and share price, and urged the court to schedule the earliest possible trial date.[242][243] On July 19, the court ruled in Twitter's favor and scheduled a five-day trial to take place the following October.[244][245] On July 22, Twitter released its earnings report for the second quarter of 2022 that showed a 1 percent decline in year-over-year company revenue and that company earnings were lower than analysts' expectations (which the company partially attributed to uncertainty created by the acquisition agreement).[246][247] On July 25, Tesla disclosed in a filing with the SEC that the company had received a second subpoena from the agency on June 13 with respect to the 2018 settlement.[248][249] On July 26, Twitter disclosed in filing with the SEC that the company had scheduled a shareholder meeting on September 13, 2022, to vote on the acquisition agreement.[250][251]

In a complaint filed by Whistleblower Aid with the SEC, the U.S. Justice Department, and the Federal Trade Commission on July 6, former Twitter security officer Peiter Zatko alleged that specific Twitter executives—including Parag Agrawal and certain board members—have repeatedly made false and misleading statements to its board, shareholders, users, regulators, and the public about privacy, security, and content moderation on the platform since 2011 in violation of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 and SEC disclosure rules including misrepresentations to Musk during the course of the acquisition bid (citing Agrawal's May 16 tweet detailing company policies for addressing fake and spam accounts).[252][253]

Author

[edit]Outside of Gensler's business and public service career, Gensler has co-authored a book with Greg Baer, a fellow Clinton Administration alum, The Great Mutual Fund Trap. The book uses empirical data to show that the average mutual fund consistently underperforms the market.[254] The book argues that actively-traded mutual funds carry high fees and lower-than-market returns, and investors should instead rely on low-fee index funds rather than constantly attempt to beat the market.

Political involvement

[edit]Gensler served as treasurer of the Maryland Democratic Party for two years,[9] and held several senior roles on the Maryland campaigns of U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski, former Lieutenant Governor Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, and Governor Martin O'Malley.[255] During the 2008 presidential campaign cycle, Gensler served as a senior advisor to Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign and later advised the Obama campaign.[255] In May 2015, Gensler was named chief financial officer of Clinton's campaign for president.[256]

Academic

[edit]Gensler is Professor of the Practice of Global Economics and Management, MIT Sloan School of Management, co-director of MIT's Fintech@CSAIL and senior adviser to the MIT Media Lab Digital Currency Initiative.[257] He focuses on the intersection of finance and technology, conducts research and teaches on blockchain technology,[258] digital currencies, financial technology and public policy. He is a member of the New York Fed Fintech Advisory Group, a group of experts in financial technology that regularly presents views and perspectives on the topic to the president of the New York Fed.[259]

Gensler won the MIT Sloan Outstanding Teacher Award based upon student nominations for the 2018–19 academic year.[257]

Personal life

[edit]Gensler lives in Baltimore with his three daughters, Anna, Lee and Isabel.[6] Gensler was married to filmmaker and photo collagist Francesca Danieli from 1986 until her death from breast cancer in 2006.[260]

Gensler is a runner and has finished nine marathons[8] and one 50-mile ultramarathon.[255] He also is a mountain climber, having summited Mt. Rainier and Mt. Kilimanjaro.[255]

References

[edit]- ^ "Gary Gensler". SEC.gov. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ "Agency Review Teams". President-Elect Joe Biden. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ Dizikes, Peter (January 19, 2021). "MIT Sloan's Gary Gensler to be nominated for chair of Securities and Exchange Commission". MIT. MIT News. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- ^ "The Problem With Hillary Clinton Using a Progressive Hero to Attack Bernie Sanders". Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "President-elect Joe Biden to name Gary Gensler as U.S. SEC chair, sources say". CNBC. January 12, 2021. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Foroohar, Rana (December 24, 2012). "The Money Cop; Gary Gensler got his start on Wall Street. Now he's cleaning it up--and taking on the biggest banking scandal since the financial crisis". Time. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Sam Gensler". September 16, 2012. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Protess, Ben (January 2, 2014). "Regulator of Wall Street Loses Its Hard-Charging Chairman". DealBook. The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hirschfeld Davis, Julie (November 3, 2002). "The Democrats' stealth fighter". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Remarks of Chairman Gary Gensler, Pikesville High School Distinguished Alumnus Assembly". cftc.gov/. CFTC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Chairman Gary Gensler". cftc.gov. CFTC. Archived from the original on October 24, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "The Gensler Twins: Identical? Don't You Believe It". Bloomberg Businessweek. November 17, 2002. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ a b Scherer, Michael (April 22, 2010). "An Ex-Goldman Man Goes After Derivatives". Time. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Wiseman, Paul (November 23, 2009). "CFTC chief Gary Gensler is out to police financial Wild West". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "President Clinton Names Gary Gensler as Under Secretary for Domestic Finance at the Department of the Treasury". The White House Office of the Press Secretary. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Fineman, Howard (April 22, 2010). "Goldman Alum Who's Trying to Fix Wall Street". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Eichenwald, Kurt (March 19, 1990). "Investment Bankers Play Football's Newest Position". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ a b "President-elect Obama announces choices for SEC, CFTC and Federal Reserve Board". Newsweek. April 22, 2010. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Protess, Ben; Bishop, Mac William (February 10, 2011). "At Center of Derivatives Debate, a Gung-Ho Regulator". DealBook. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ "Gensler, Gary". OpenSecrets. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Bloomberg Politics - Bloomberg". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Jan 20 - Subcabinet Nominations". wh.gov. The White House. January 20, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Presidential Nominations". thomas.gov. Archived from the original on December 21, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ "Remarks of CFTC Chairman Gary Gensler Swearing-In Ceremony". cftc.gov. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Miedema, Douwe (January 3, 2014). "Swaps regulator Gensler: banker turned Wall Street scourge". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ "Gary Gensler, derivatives cop". The Economist. September 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Nocera, Joe (November 15, 2013). "The Little Agency That Could". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ Chon, Gina (December 30, 2013). "Gary Gensler defends record as he leaves CFTC". Financial Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Remarks of Chairman Gary Gensler before the ISDA European Conference". cftc.gov/. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ a b Protess, Ben (August 12, 2012). "Libor Case Energizes a Wall Street Watchdog". DealBook. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- ^ Bischoff, Victoria; McGagh, Michelle (February 6, 2013). "Q&A: what is Libor and what did the banks do to it?". Citywire Money. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Masters, Brooke; Stafford, Philip (April 22, 2013). "CFTC's Gensler says Libor 'unsustainable'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Gensler-Corzine relationship complicates regulator's probe of MF Global". The Washington Post. November 4, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Gensler grilled over MF Global collapse". Farm Progress. December 8, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "CFTC, Gensler Criticized Over Handling of MF Global". Wall Street Journal. May 21, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Gensler's Recusal Criticized in CFTC Watchdog's MF Global Report". Bloomberg. May 22, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Gary Gensler, Former Commodity Futures Trading Commission Chairman, Wins Frankel Fiduciary Prize" (PDF). The Institute for the Fiduciary Standard. August 4, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Financial Consumer Protection Commission, Maryland". msa.maryland.gov. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Ian (September 26, 2023). "Marylanders hit hard by student loan debt". The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "Financial Consumer Protection Act of 2018" (PDF). Maryland General Assembly. Department of Legislative Services. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ Service, Capital News (April 23, 2019). "Bill Would Provide Protections to Student Loan Borrowers". Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ "Agency Review Teams". President-Elect Joe Biden. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "Brown Statement at Executive Session to Vote on Nominees and Subcommittees" (Press release). United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs. March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ "On the Nomination (Confirmation: Gary Gensler, of Maryland, to be a Member of the Securities and Exchange Commission)" United States Senate, April 14, 2021

- ^ "On the Nomination (Confirmation: Gary Gensler, of Maryland, to be a Member of the Securities and Exchange Commission)" United States Senate, April 20, 2021

- ^ Franck, Thomas (September 14, 2021). "Senators demand cryptocurrency regulation guidance from SEC Chair Gary Gensler". CNBC. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (September 15, 2021). "The SEC is 'short-staffed' and it needs more help to tackle everything from crypto to China, Gensler says". CNBC. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Lane, Sylvan (September 14, 2021). "Gensler compares cryptocurrency market, regulations to 'wild west'". The Hill. Nexstar Media Group. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "Securities and Exchange Commission Oversight Hearing". C-SPAN. September 14, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "The Path Forward: Cryptocurrency with Gary Gensler". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ Macheel, Tanaya (October 6, 2021). "Bitcoin jumps to nearly 5-month high, topping $55,000 on Wednesday". CNBC. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ "Oversight of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission: Wall Street's Cop Is Finally Back on the Beat". U.S. House Financial Services Committee. October 5, 2021. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (October 15, 2021). "The SEC is poised to allow the first bitcoin futures ETFs to begin trading, source says". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Macheel, Tanaya (October 18, 2021). "First bitcoin futures ETF to make its debut Tuesday on the NYSE, ProShares says". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (August 3, 2021). "What the SEC chair's comments on crypto mean for a possible bitcoin ETF". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Pisani, Bob (February 4, 2022). "SEC Chairman Gary Gensler embarks on ambitious regulatory agenda. What it means for investors". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "A three-way fight to shape the future of digital finance has begun". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ Alessandrini, Sarah (April 4, 2022). "SEC Chair Gensler says agency is planning greater oversight of crypto markets to protect investors". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Evans, Brian (May 11, 2022). "SEC chief Gary Gensler says crypto exchanges are 'market making against their customers'". Yahoo! Finance. Yahoo!. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Securities and Exchange Commission Oversight Hearing". U.S. House Appropriations Committee. May 26, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Matthews, Chris (May 26, 2021). "SEC chairman says Americans need a 'cop on the beat' to protect investors from crypto fraud". MarketWatch. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Kiernan, Paul (May 18, 2022). "More Crypto Market Turmoil Is Predicted by SEC Chairman Gary Gensler". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (June 7, 2022). "Bipartisan crypto regulatory overhaul would treat most digital assets as commodities under CFTC oversight". CNBC. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Kiernan, Paul (June 14, 2022). "Crypto Legislation Could Undermine Market Regulations, Gensler Says". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Goswami, Rohan (January 12, 2023). "Crypto firms Genesis and Gemini charged by SEC with selling unregistered securities". CNBC. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (May 6, 2021). "SEC Chair Gary Gensler raises concerns about Robinhood, trading gamification and social media hype". CNBC. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (May 20, 2021). "SEC chair Gensler says agency will enforce rules 'aggressively' against bad actors". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "GameStop and Protecting Investors". C-SPAN. May 6, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Game Stopped? Who Wins and Loses When Short Sellers, Social Media, and Retail Investors Collide, Part III (PDF) (Report). Vol. 117–22. U.S. House Committee on Financial Services/U.S. Government Printing Office. May 6, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Finn, Teaganne (May 26, 2021). "Warren Asks Gensler to Remove Accounting Oversight Board Members". Bloomberg News. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Mejdrich, Kellie (June 4, 2021). "SEC fires Republican audit watchdog after push from Warren, Sanders". Politico. Axel Springer SE. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Maurer, Mark (June 4, 2021). "SEC Removes Chairman of Audit Watchdog". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Eaglesham, Jean (June 17, 2021). "SEC Investigating Former Chair of Auditing Industry Regulator". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Osipovich, Alexander (June 9, 2021). "SEC to Review Market Structure as Meme Stocks Stir Frenzy". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (August 30, 2021). "Robinhood Stock Drops After SEC Chairman Warns on Payment for Order Flow". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave (June 7, 2021). "SEC Chairman Calls for New Restrictions on Executive Stock-Trading Plans". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave (June 30, 2021). "Robinhood Agrees to Pay $70 Million to Settle Regulatory Investigation". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Maggie (July 29, 2021). "Robinhood falls in its public market debut, closes more than 8% lower at $34.82 per share". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Rudegeair, Peter; Driebusch, Corrie; McCabe, Caitlin (July 29, 2021). "Robinhood's Stock Price Falls After IPO". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (August 6, 2021). "SEC approves Nasdaq's plan to boost diversity on corporate boards". CNBC. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Kiernan, Paul; Rudegeair, Peter (August 27, 2021). "SEC Launches Review of Online Strategies Used by Brokers, Advisers". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (December 2, 2021). "SEC finalizes rule that allows it to delist foreign stocks for failure to meet audit requirements". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Frank, Robert (December 1, 2021). "CEOs and insiders sell a record $69 billion of their stock, and the year isn't over yet". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (December 15, 2021). "SEC Chair Gary Gensler wants stronger insider trading rules as executive stock sales hit records". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (January 27, 2022). "Robinhood Meme-Stock Negligence Suit Is Rejected by Judge". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (May 18, 2022). "Tough questions await SEC Chair Gensler as he seeks funding for his regulatory agenda". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Request for the Federal Trade Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission". U.S. House Appropriations Committee. May 18, 2022. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (June 7, 2022). "SEC's Gensler speaks Wednesday, and rules that overhaul market operations could be coming". CNBC. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. SEC chief Gary Gensler unveils plan to overhaul Wall Street stock trading". CNBC. June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ Macheel, Tanaya (May 12, 2022). "Robinhood shares pop more than 20% after Sam Bankman-Fried buys 7.6% stake". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ McCaffrey, Orla (May 12, 2022). "FTX Founder Sam Bankman-Fried Buys 7.6% Stake in Robinhood". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Li, Yun (June 27, 2022). "Robinhood shares jump 14% on report FTX may be exploring a deal". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Huang, Vicky Ge; Miao, Hannah (June 27, 2022). "Robinhood Shares Soar on Takeover Hopes". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Melinek, Jacquelyn (June 27, 2022). "FTX says no active talks to buy Robinhood". TechCrunch. Yahoo, Inc. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Macheel, Tanaya (May 19, 2022). "Crypto exchange FTX U.S. moves into stock trading". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Rooney, Kate (May 23, 2022). "Crypto exchange FTX quietly shops for brokerage start-ups amid move into stock trading, sources say". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (July 20, 2022). "Robinhood Was Behind Phantom Surge in Berkshire Hathaway Trade Volume, Study Finds". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Li, Yun (July 20, 2022). "The reason behind a mysterious trading surge in stocks like Berkshire Hathaway has been revealed". CNBC. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Bartlett, Robert P.; McCracy, Justin; O'Hara, Maureen (July 20, 2022). "A Fractional Solution to a Stock Market Mystery". Social Science Research Network. Elsevier. SSRN 4167890.

- ^ Geman, Ben (January 28, 2021). "Microsoft backs direct air capture player Climeworks". Axios. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Calma, Justine (September 9, 2021). "How the largest direct air capture plant will suck CO2 out of the atmosphere". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Joppa, Lucas; Luers, Amy; Willmott, Elizabeth; Friedmann, S. Julio; Hamburg, Steven P.; Broze, Rafael (September 29, 2021). "Microsoft's million-tonne CO2-removal purchase — lessons for net zero". Nature. 597 (7878): 629–632. Bibcode:2021Natur.597..629J. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02606-3. S2CID 238229298. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (January 16, 2020). "Microsoft Pledges To Remove From The Atmosphere All The Carbon It Has Ever Emitted". NPR. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Calma, Justine (January 16, 2020). "Microsoft wants to capture all of the carbon dioxide it's ever emitted". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Calma, Justine (January 28, 2021). "Microsoft made a giant climate pledge one year ago — here's where it's at now". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Ryan (February 5, 2021). "Bitcoin's wild ride renews worries about its massive carbon footprint". CNBC. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Criddle, Christina (February 10, 2021). "Bitcoin consumes 'more electricity than Argentina'". BBC. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Webb, Samuel (May 19, 2022). "Crypto crash 'will not affect Bitcoin mining's climate cost'". Yahoo! News. Yahoo, Inc. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Kovach, Steve (February 8, 2021). "Tesla buys $1.5 billion in bitcoin, plans to accept it as payment". CNBC. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (April 15, 2021). "Apple launches $200 million fund for climate change". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Bussewitz, Cathy (February 7, 2022). "Report: Climate pledges from Amazon, others weaker than they seem". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor 2022: Assessing the Transparency and Integrity of Companies' Emission Reduction and Net-Zero Targets (PDF) (Report). NewClimate Institute. 2022. pp. 54–58, 76–78. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Temple, James (June 23, 2020). "Amazon creates a $2 billion climate fund, as it struggles to cut its own emissions". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Temple, James (November 2, 2020). "How Amazon's offsets could exaggerate its progress toward "net zero" emissions". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Annie (June 30, 2021). "Amazon's carbon emissions rose 19% in 2020 even as Covid-19 pushed global levels down". CNBC. Retrieved July 14, 2022.

- ^ Joselow, Maxine (February 22, 2022). "Court ruling on social cost of carbon upends Biden's climate plans". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Anna (March 16, 2022). "Appellate court rules Biden can consider climate damage in policymaking". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Pete (May 26, 2022). "Supreme Court won't block Biden rule on societal cost of greenhouse gases". CNBC. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (May 26, 2022). "Supreme Court Allows Greenhouse Gas Cost Estimates". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Robert; Phillips, Anna (May 26, 2022). "Supreme Court allows Biden climate regulations while fight continues". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (February 15, 2022). "ConocoPhillips is selling extra gas to bitcoin miners in North Dakota". CNBC. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (March 21, 2022). "The SEC wants to know a lot more about what companies are doing about climate change". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Franck, Thomas (March 21, 2022). "SEC proposes broad climate rules as Chair Gensler says risk disclosure will help investors". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ The Editorial Board (March 21, 2022). "Opinion | Gary Gensler Stages a Climate Coup". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (March 26, 2022). "Exxon is mining bitcoin in North Dakota as part of its plan to slash emissions". CNBC. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (April 12, 2022). "Stripe teams up with major tech companies to commit $925 million toward carbon capture". CNBC. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Brigham, Katie (June 28, 2022). "Why Big Tech is pouring money into carbon removal". CNBC. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Sorkin, Andrew Ross; Giang, Vivian; Gandel, Stephen; Hirsch, Lauren; Livni, Ephrat; Gross, Jenny; Gallagher, David F.; Schaverien, Anna (May 19, 2022). "Elon Musk's Next Target". The New York Times. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Frangoul, Anmar (July 1, 2022). "Elon Musk is smart — but he doesn't understand ESG, tech CEO says". CNBC. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Newburger, Emma (May 25, 2022). "SEC unveils rules to prevent misleading claims and enhance disclosures by ESG funds". CNBC. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave (June 10, 2022). "SEC Is Investigating Goldman Sachs Over ESG Funds, Sources Say". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ "Exxon, BP, Shell and Chevron Executives Testify on Climate Change". C-SPAN. October 28, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Power of Big Oil, Part III: Delay". FRONTLINE. Season 40. Episode 12. May 3, 2022. PBS. WGBH. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ Woods, Darren (June 24, 2022). "How Exxon Mobil plans to meet the energy transition: Extended Interview with CEO Darren Woods" (Interview). Interviewed by David Faber. CNBC. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Winograd, Amanda (June 23, 2022). "Exxon Mobil is at a crossroads as climate crisis spurs clean energy transition". CNBC. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "Plastic Wars". FRONTLINE. Season 38. Episode 15. March 31, 2020. PBS. WGBH. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Newburger, Emma; Mangan, Dan (June 30, 2022). "Supreme Court limits EPA authority to set climate standards for power plants". CNBC. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (July 1, 2022). "The Supreme Court's EPA ruling is a big setback for fighting climate change, but not a death knell". CNBC. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Iacurci, Greg (July 5, 2022). "Supreme Court limited EPA's ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Here's how investors can buy a carbon-conscious fund". CNBC. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ Li, Yun (March 2, 2021). "Shares of Rocket Companies, a large short target of hedge funds, jump more than 70%". CNBC. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Tompor, Susan (March 2, 2021). "Rocket Companies stock soars 70% on speculative trading, mirroring GameStop rally". Detroit Free Press. Gannett. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ McCaffrey, Orla (March 3, 2021). "Rocket Stock Is the New Meme Trade. Move Over, GameStop". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Grzelewski, Jordyn (March 3, 2021). "After GameStop-like surge, Rocket stock frenzy shows signs of subsiding". The Detroit News. Digital First Media. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Katanga (September 14, 2021). "U.S. SEC "close" to publishing report on Gamestop meme saga - SEC Chair". Reuters. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Pisani, Bob (September 23, 2021). "Investors brace for SEC Chair Gensler's report on GameStop and how brokerages get paid". CNBC. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Li, Yun (October 18, 2021). "SEC says brokers enticed by payment for order flow are making trading into a game to lure investors". CNBC. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Bain, Ben (October 18, 2021). "SEC GameStop report debunks conspiracies, backs commission chief's plan". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Staff Report on Equity and Options Market Structure Conditions in Early 2021 (PDF) (Report). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. October 14, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Zubrow, Keith; Gavrilovic, Maria; Ortiz, Alex (October 4, 2021). "Whistleblower's SEC complaint: Facebook knew platform was used to "promote human trafficking and domestic servitude"". 60 Minutes Overtime. CBS News. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Horwitz, Jeff (September 13, 2021). "Facebook Says Its Rules Apply to All. Company Documents Reveal a Secret Elite That's Exempt". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Bursztynsky, Jessica; Feiner, Lauren (September 14, 2021). "Facebook documents show how toxic Instagram is for teens, Wall Street Journal reports". CNBC. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Pelley, Scott (October 4, 2021). "Whistleblower: Facebook is misleading the public on progress against hate speech, violence, misinformation". 60 Minutes. CBS News. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (October 3, 2021). "Facebook whistleblower reveals identity, accuses the platform of a 'betrayal of democracy'". CNBC. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ "Facebook Whistleblower Testifies on Protecting Children Online". C-SPAN. October 5, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (October 5, 2021). "Facebook whistleblower: The company knows it's harming people and the buck stops with Zuckerberg". CNBC. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Bidar, Musadiq (October 28, 2021). "Facebook to change corporate name to Meta". CBS News. Retrieved May 16, 2022.

- ^ Zakrzewski, Cat (February 18, 2022). "Facebook whistleblower alleges executives misled investors about climate, covid hoaxes in new SEC complaint". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Mangan, Dan (November 18, 2021). "Sen. Elizabeth Warren calls on SEC to investigate Trump SPAC deal with DWAC for possible securities violations". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Sigalos, MacKenzie (October 20, 2021). "Trump announces social media platform launch plan, SPAC deal". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Mangan, Dan; Li, Yun; Wilkie, Christina (October 21, 2021). "Shares of Trump-linked SPAC close up 350% following news of social media deal". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Goldstein, Matthew; Hirsch, Lauren; Enrich, David (October 29, 2021). "Trump's $300 Million SPAC Deal May Have Skirted Securities Laws". The New York Times. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Mangan, Dan (December 6, 2021). "Trump SPAC under investigation by federal regulators, including SEC". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (February 18, 2022). "Influencers beware: promoting the wrong crypto could mean facing a class-action lawsuit". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (July 7, 2022). "Donald Trump left the board of his social media company weeks before federal subpoenas, filing shows". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (July 7, 2022). "Exclusive: Trump left Sarasota media company weeks before federal subpoenas were issued". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Gannett. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Morris, Chris (June 14, 2022). "SEC expands investigation into Donald Trump's Truth Social". Fortune.

- ^ Calia, Mike (June 27, 2022). "Trump SPAC deal threatened by federal criminal probe". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Calia, Mike (July 1, 2022). "Trump media company subpoenaed in federal criminal probe of SPAC deal". CNBC. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Annie (July 19, 2022). "Amazon sues thousands of Facebook group administrators over fake reviews". CNBC. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Purnell, Newley (July 19, 2022). "Amazon Sues Facebook Group Administrators Over Fake Reviews". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Bursztynsky, Jessica; Kolodny, Lora (November 6, 2021). "Elon Musk says he's using a Twitter poll to determine the future of 10% of his Tesla shares". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Wall, Robert (December 2, 2021). "Elon Musk's Tesla Share-Selling Spree Tops $10 Billion". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Hetzner, Christiaan (December 3, 2021). "Elon Musk has now sold more than $10 billion in Tesla stock, part of a record wave of CEOs cashing out". Fortune. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Annie (December 6, 2021). "Tesla shares fall into bear market territory after SEC reportedly opens probe into solar panel defects". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Ferris, Robert (August 7, 2018). "Tesla shares surge 10% after Elon Musk shocks market with tweet about going private". CNBC. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Salinas, Sara (September 27, 2018). "SEC charges Tesla CEO Elon Musk with fraud". CNBC. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (September 30, 2018). "Elon Musk agrees to pay $20 million and quit as Tesla chairman in deal with SEC". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Salinas, Sara (February 20, 2019). "Elon Musk tweeted, then revised, Tesla financial guidance. He probably shouldn't have". CNBC. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ Statt, Nick (February 25, 2019). "Elon Musk might be held in contempt of court over a Tesla tweet". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (April 27, 2019). "Elon Musk and SEC reach an agreement over tweeting". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "US SEC commissioner decries agency's deal with Tesla's Musk". CNBC. April 30, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Trudell, Craig (July 30, 2019). "Elon Musk claims Tesla solar production will jump. Does that violate his SEC accord?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Bursztynsky, Jessica (May 1, 2020). "Tesla shares tank after Elon Musk tweets the stock price is 'too high'". CNBC. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Elliott, Rebecca (June 1, 2021). "Tesla Failed to Oversee Elon Musk's Tweets, SEC Argued in Letters". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora (June 1, 2021). "SEC said Elon Musk's Tesla tweets violated settlement agreement, WSJ reports". CNBC. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Elliott, Rebecca; Michaels, Dave (February 7, 2022). "SEC Subpoenas Tesla Seeking Information Linked to Elon Musk Settlement". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (February 7, 2022). "The SEC subpoenas Tesla over one of Elon Musk's tweets again". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (February 17, 2022). "Elon Musk tells a judge the SEC's 'endless' investigation is stifling his free speech". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (February 17, 2022). "Elon Musk says the SEC is gunning for his free speech rights". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Elliott, Rebecca (February 18, 2022). "Elon Musk's Accusation of Harassment Countered by SEC". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Roth, Emma (February 19, 2022). "Elon Musk's claims of 'broken' promises denied by the SEC". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora; Wayland, Michael (February 21, 2022). "Tesla CEO Elon Musk accuses SEC of leaking information from federal probe". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (February 22, 2022). "Elon Musk accuses the SEC of illegally leaking details of its Tesla investigation". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora (February 24, 2022). "Judge rejects Tesla CEO Elon Musk's attempt to bring SEC before the court". CNBC. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave (February 24, 2022). "SEC Probes Trading by Elon Musk and Brother in Wake of Tesla CEO's Sales". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Annie; Kolodny, Lora (February 24, 2022). "SEC reportedly probes Tesla CEO Elon Musk and brother over recent stock sales". CNBC. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave; Elliott, Rebecca (March 8, 2022). "Elon Musk Seeks to Terminate 2018 Fraud Settlement With SEC". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (March 8, 2022). "Elon Musk claims he was coerced into settling with the SEC over his 'funding secured' tweet". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Krisher, Tom (March 22, 2022). "SEC claims authority to subpoena Elon Musk over tweets". PBS NewsHour. WETA. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (March 29, 2022). "Elon Musk cites Eminem song in latest volley with the SEC". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Maruf, Ramishah (April 3, 2022). "Elon Musk's latest court filing against the SEC quotes Eminem". CNN Business. CNN. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ Imbert, Fred (April 4, 2022). "Twitter shares close up 27% after Elon Musk takes 9% stake in social media company". CNBC. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Porter, Jon (April 4, 2022). "Elon Musk buys 9.2 percent of Twitter amid complaints about free speech". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (April 5, 2022). "Elon Musk updates the paperwork on his shocking Twitter purchase to avoid extra SEC drama". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Albergotti, Reed (April 6, 2022). "Elon Musk delayed filing a form and made $156 million". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (April 11, 2022). "Elon Musk's SEC filings reserve the right to buy a larger stake in Twitter". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Shead, Sam (April 13, 2022). "Twitter investors sue Elon Musk for failing to promptly disclose the size of his stake". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Subin, Samantha (April 14, 2022). "Elon Musk offers to buy Twitter for $43 billion, so it can be 'transformed as private company'". CNBC. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Koebler, Jason (April 21, 2022). "Elon Musk Secures $46.5 Billion to Buy Twitter: SEC Filing". Vice. Vice Media. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora (April 16, 2022). "Elon Musk's tweets about taking Tesla private were false, new court filing says". CNBC. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Hawkins, Andrew J. (April 14, 2022). "Elon Musk says the SEC's investigations into Tesla are 'like having a gun to your child's head'". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (April 22, 2022). "House Republicans demand Twitter's board preserve all records about Musk's bid to buy the company". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Krisher, Tom; O'Brien, Matt (April 25, 2022). "Elon Musk reaches agreement to acquire Twitter for about $44 billion". PBS NewsHour. WETA. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (April 25, 2022). "Twitter accepts Elon Musk's buyout deal". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Katersky, Aaron (April 27, 2022). "Elon Musk's bid to end SEC tweet settlement rejected by judge". ABC News. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ O'Donnell, Katy (April 27, 2022). "Judge rejects Elon Musk's bid to end SEC tweet settlement". Politico. Axel Springer SE. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Livni, Ephrat (April 30, 2022). "Musk Joins Moguls to Kill S.E.C. 'Gag Orders' at the Supreme Court". The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Siddiqui, Faiz; Albergotti, Reed; Dwoskin, Elizabeth; Lerman, Rachel (May 13, 2022). "Elon Musk says Twitter deal is on hold, putting bid on shaky ground". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Shead, Sam (May 13, 2022). "Elon Musk says Twitter deal on hold pending details on fake accounts; shares sink 9%". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Michaels, Dave (May 11, 2022). "Elon Musk's Belated Disclosure of Twitter Stake Triggers Regulators' Probes". The Wall Street Journal. News Corp. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Bursztynsky, Jessica (May 16, 2022). "Twitter CEO explains how the company actually fights spambots in rebuttal to Musk". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Shead, Sam (May 17, 2022). "Elon Musk says Twitter deal 'cannot move forward' until he has clarity on fake account numbers". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Lawler, Richard (May 17, 2022). "Elon Musk's latest stunt: calling on the SEC to investigate Twitter's user numbers". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora (May 17, 2022). "Elon Musk calls on SEC to evaluate Twitter user numbers". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Annie (May 17, 2022). "Musk met Twitter execs for 3 days before making a bid, unclear if they discussed bots". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Feiner, Lauren (May 17, 2022). "New filing reveals the full story behind Musk's bid to buy Twitter". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ "In a faceoff with Elon Musk, the SEC blinked". CNBC. May 24, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ^ Kolodny, Lora (May 26, 2022). "Twitter shareholders sue Elon Musk and Twitter over chaotic deal". CNBC. Retrieved May 28, 2022.