Literacy test

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (June 2020) |

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write. Literacy tests have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants.

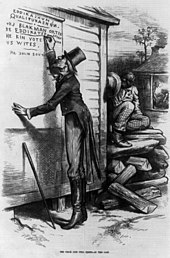

Between the 1850s[1] and 1960s, literacy tests were used as an effective tool for disenfranchising African Americans in the Southern United States. Literacy tests were typically administered by white clerks who could pass or fail a person at their discretion based on race.[2] Illiterate whites were often permitted to vote without taking these literacy tests because of grandfather clauses written into legislation.[2]

Other countries, notably Australia, as part of its White Australia policy, and South Africa adopted literacy tests either to exclude certain racialized groups from voting or to prevent them from immigrating to the country.[3]

Voting

[edit]From the 1890s to the 1960s, many state governments administered literacy tests to prospective voters, to test their literacy in order to vote. The first state to establish literacy tests in the United States was Connecticut.[4]

State legislatures employed literacy tests as part of the voter registration process starting in the late 19th century. Literacy tests, along with poll taxes, residency and property restrictions, and extra-legal activities (violence and intimidation)[5][better source needed] were all used to deny suffrage to African Americans.

The first formal voter literacy tests were introduced in 1890. At first, whites were generally exempted from the literacy test if they meet alternate requirements that in practice excluded blacks, such as a grandfather clause, or a finding of "good moral character", the latter's testimony of which was often asked only of white people.[citation needed] Some locales administered separate literacy tests, with a more simplified literacy tests being administered to whites who had registered to vote.[citation needed]

In Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections (1959), the U.S. Supreme Court held that literacy tests were not necessarily violations of Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment nor of the Fifteenth Amendment. Southern states abandoned the literacy test only when forced to do so by federal legislation in the 1960s. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 stated that literacy tests used as a qualification for voting in federal elections be administered wholly in writing and only to persons who had completed at least six years of formal education.

To curtail the use of literacy tests, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Act prohibited jurisdictions from administering literacy tests, among other measures, to citizens who attained a sixth-grade education in an American school in which the predominant language was Spanish, such as schools in Puerto Rico.[6] The Supreme Court upheld this provision in Katzenbach v. Morgan (1966). Although the Court had earlier held in Lassiter that literacy tests did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment,[7] in Morgan the Court held that Congress could enforce Fourteenth Amendment rights—such as the right to vote—by prohibiting conduct it deemed to interfere with such rights, even if that conduct may not be independently unconstitutional.[8][9]

As originally enacted, the Voting Rights Act also suspended the use of literacy tests in all jurisdictions in which less than 50% of voting-age residents were registered as of November 1, 1964, or had voted in the 1964 presidential election. Congress amended the Act in 1970 and expanded the ban on literacy tests to the entire country.[10] The Supreme Court then upheld the ban as constitutional in Oregon v. Mitchell (1970), but just for federal elections. The Court was deeply divided in this case, and a majority of justices did not agree on a rationale for the holding.[11][12]

Immigration

[edit]When introduced in the 1890s, the literacy test was a device to restrict the total number of immigrants while not offending the large element of ethnic voters. The "old" immigration (British, Dutch, Irish, German, Scandinavian) had fallen off and was replaced by a "new" immigration from Italy, Russia and other points in Southern and eastern Europe. The "old" immigrants were voters and strongly approved of restricting the "new" immigrants. The 1896 Republican platform called for a literacy test.[13]

The American Federation of Labor took the lead in promoting literacy tests that would exclude illiterate immigrants, primarily Eastern Europe and countries that had national waters in the Mediterranean Sea.[14]

Corporate industry however, needed workers for its mines and factories and opposed any restrictions on immigration.[15] In 1906, the House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon, a conservative Republican, worked aggressively to defeat a proposed literacy test for immigrants. A product of the western frontier, Cannon felt that moral probity was the only acceptable test for the quality of an immigrant. He worked with Secretary of State Elihu Root and President Theodore Roosevelt to set up the "Dillingham Commission," a blue ribbon body of experts that produced a 41-volume study of immigration. The Commission recommended a literacy test and the possibility of annual quotas.[16] Presidents Cleveland and Taft vetoed literacy tests in 1897 and 1913. President Wilson did the same in 1915 and 1917, but the test was passed over Wilson's second veto.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Literacy Tests and the Right To Vote - ConnecticutHistory.org". connecticuthistory.org. 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b "How Jim Crow-Era Laws Suppressed the African American Vote for Generations". HISTORY. 2023-08-08.

- ^ Lake, Marilyn. (2006). Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective. Australian National University. pp. 209–230. ISBN 978-1-920942-45-8. OCLC 1135556055.

- ^ "Literacy Tests and the Right to Vote". 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Civil Rights Movement -- Literacy Tests & Voter Applications". www.crmvet.org.

- ^ Voting Rights Act of 1965 § 4(e); 52 U.S.C. § 10303(e) (formerly 42 U.S.C. § 1973b(e))

- ^ Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections, 360 U.S. 45 (1959)

- ^ Buss, William G. (January 1998). "Federalism, Separation of Powers, and the Demise of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act". Iowa Law Review. 83: 405–406. Retrieved January 7, 2014. (Subscription required.)

- ^ Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966), pp. 652–656

- ^ Williamson, Richard A. (1984). "The 1982 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act: A Statutory Analysis of the Revised Bailout Provisions". Washington University Law Review. 62 (1): 5–9. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ Tok ji, Daniel P. (2006). "Intent and Its Alternatives: Defending the New Voting Rights Act" (PDF). Alabama Law Review. 58: 353. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970), pp. 188–121

- ^ Gratton, Brian (2011). "Demography and Immigration Restriction in American History". In Goldstone, Jack A. (ed.). Political Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics. Oup USA. pp. 159–75. ISBN 978-0-19-994596-2.

- ^ Lane, A. T. (1984). "American Trade Unions, Mass Immigration and the Literacy Test: 1900–1917". Labor History. 25 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1080/00236568408584739.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia (1994). "The political economy of immigration restriction in the United States, 1890 to 1921". The regulated economy: A historical approach to political economy. U. of Chicago Press. pp. 223–258. ISBN 0-226-30110-9.

- ^ Zeidel, Robert F. (1995). "Hayseed Immigration Policy: 'Uncle Joe' Cannon and the Immigration Question". Illinois Historical Journal. 88 (3): 173–188. JSTOR 40192956.

- ^ Bischoff, Henry (2002). Immigration Issues. Greenwood. p. 156. ISBN 9780313311772.

Further reading

[edit]- Petit, Jeanne D. (2010). The Men and Women We Want: Gender, Race, and the Progressive Era Literacy Test Debate. University of Rochester Press.

External links

[edit]- Are You "Qualified" to Vote? Alabama literacy test ~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

- Naturalization literacy test still in use today