List of photographs of Abraham Lincoln

There are 130 known photographs of Abraham Lincoln.

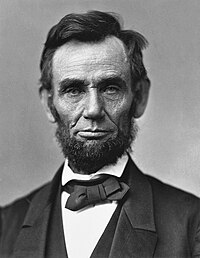

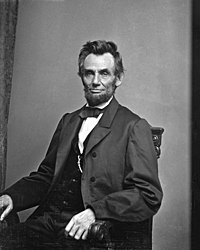

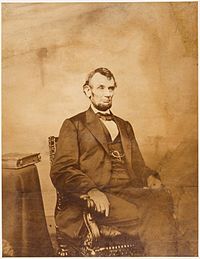

Lincoln's features were the despair of every artist who undertook his portrait. The writer saw nearly a dozen, one after another, soon after the first nomination to the presidency, attempt the task. They put into their pictures the large rugged features, and strong prominent lines; they made measurements to obtain exact proportions; they "petrified" some single look, but the picture remained hard and cold. Even before these paintings were finished it was plain to see that they were unsatisfactory to the artists themselves, and much more so to the intimate friends of the man; this was not he who smiled, spoke, laughed, charmed. The picture was to the man as the grain of sand to the mountain, as the dead to the living. Graphic art was powerless before a face that moved through a thousand delicate gradations of line and contour, light and shade, sparkle of the eye and curve of the lip, in the long gamut of expression from grave to gay, and back again from the rollicking jollity of laughter to that serious, far-away look that with prophetic intuitions beheld the awful panorama of war, and heard the cry of oppression and suffering. There are many pictures of Lincoln; there is no portrait of him.

— John George Nicolay, Secretary to President Lincoln.[1]

| Image | Date | Photographer | Location | Technique | Owner | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

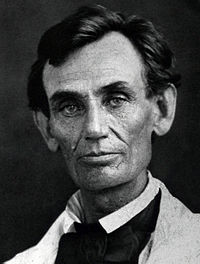

1846 or 1847 | Nicholas H. Shepherd | Springfield, Illinois | Daguerreotype, quarter plate[2] | Library of Congress | This daguerreotype is the earliest confirmed photographic image of Abraham Lincoln. It was reportedly made in 1846 by Nicholas H. Shepherd shortly after Lincoln was elected to the United States House of Representatives. Shepherd's Daguerreotype Miniature Gallery, which he advertised in the Sangamo Journal, was located in Springfield over the drug store of J. Brookie. Shepherd also studied law at the law office of Lincoln and Herndon.[3] |

|

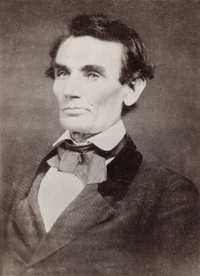

October 27, 1854 | Johan Carl Frederic Polycarpus Von Schneidau[4] | Chicago, Illinois | Gelatin silver print of a presumed lost daguerreotype[5] | The second earliest known photograph of Lincoln. From a photograph owned originally by George Schneider, former editor of the Illinois Staats-Zeitung, the most influential anti-slavery German newspaper of the West. Mr. Schneider first met Mr. Lincoln in 1853, in Springfield. "He was already a man necessary to know", says Mr. Schneider. In 1854 Mr. Lincoln was in Chicago, and Isaac N. Arnold invited Mr. Schneider to dine with Mr. Lincoln. After dinner, as the gentlemen were going down town, they stopped at an itinerant photograph gallery, and Mr. Lincoln had this picture taken for Mr. Schneider.[6] | |

|

February 28, 1857 | Alexander Hessler | Chicago, Illinois[7] | Gelatin silver print from the lost original negative | Lincoln immediately prior to his Senate nomination. The original negative was burned in the Great Chicago Fire.[8] | |

|

May 27, 1857 | Amon T. Joslin | Danville, Illinois | Ambrotype[9] | Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection, Allen County Public Library | Although some historians have dated this photograph during the court session of November 13, 1859, and others have placed it as early as 1853, most authorities now believe it was taken on May 27, 1857. The photographer Amon T. Joslin owned "Joslin's Gallery" located on the second floor of a building adjoining the Woodbury Drug Store, in Danville, IL. This was one of Lincoln's favorite stopping places in Vermilion County, Illinois, while he was a traveling lawyer. Joslin photographed Abraham Lincoln twice at this sitting. Lincoln kept one copy and gave the other to his friend, Thomas J. Hilyard, deputy sheriff of Vermilion County. Today, one original resides in the Illinois State Historical Library.[10] |

|

1858 | Roderick M. Cole | Peoria, Illinois | Daguerreotype (?)[11] | Benjamin Shapell Family Manuscript Foundation |

Lincoln liked this image and often signed photographic prints for admirers. In fact, in 1861, he even gave a copy to his stepmother. The image was extensively employed on campaign ribbons in the 1860 Presidential campaign, and Lincoln "often signed photographic prints for visitors."[12] |

|

1858 (?) | unknown | unknown | Tintype[13] | National Lincoln Museum (Old Ford's Theatre)[14] | This is the only extant original tintype of Lincoln[14] |

|

1858 (?) | Ohio (?) | Photographic copy of a lost daguerreotype[15] | Anthony L. Maresh collection | A Civil War soldier from Parma, Ohio, was the original owner of this portrait, published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on February 12, 1942, from a print in the Anthony L. Maresh collection. Possibly it is a photographic copy of one of two daguerreotypes, both now lost, taken in Ohio.[15] | |

|

1858 (?) | Springfield, Illinois | Photographic copy | unknown | In 1858, Lincoln squared off against Stephen Douglas for Illinois' Senate seat. The battle sparked seven heated debates on slavery. Here, supporters gather outside Lincoln's Springfield home. Lincoln is the tall, white figure by the doorway.[16] | |

|

May 7, 1858 | Abraham M. Byers | Beardstown, Illinois[17] | Ambrotype | University of Nebraska | Formerly in the Lincoln Monument collection at Springfield, Illinois. Mr. Lincoln wore a linen coat on the occasion. The picture is regarded as a good likeness of him as he appeared during the Lincoln Douglas campaign.[18] |

|

May 25, 1858 | Samuel G. Alschuler | Urbana, Illinois[19] | Library of Congress |

| |

|

July 18, 1858 | Preston Butler[21] | Springfield, Illinois | Gelatin silver print of a lost carbon enlargement of the lost ambrotype | This image was presumably taken by Preston Butler the day after Lincoln delivered a speech in Springfield in which Lincoln urges that slavery be placed on the course of "ultimate extinction". He attacks Stephen Douglas and defends himself by stating that he supports the principles of equality put forth in the Declaration of Independence. This speech preceded his debates with Douglas.[22] | |

|

August 26, 1858 | T. P. Pearson[23] | Macomb, Illinois | Ambrotype |

| |

|

September 26, 1858 | attributed to Christopher S. German[25] | Springfield, Illinois | unknown | Chicago History Museum |

|

|

October 1, 1858 | Calvin Jackson[27] | Pittsfield, Illinois | Ambrotype | Library of Congress | On the afternoon of Friday, October 1, 1858, Lincoln had a luncheon at the home of his attorney friend, Daniel H. Gilmer in Pittsfield, Illinois. Lincoln then headed across the street to the town square, where he spoke for two hours. Following the address, Lincoln, at the request of Gilmer, went to the portable canvas photo gallery of Calvin Jackson on the northeast corner of the square and sat for two ambrotype poses. The photos were soon processed, but one was not finished, probably because it had been overexposed. Lincoln requested that copies of the other be delivered to two Pittsfield friends the following day.[28] |

|

October 11, 1858 | William Judkins Thomson[29] | Monmouth, Illinois | National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution | This ambrotype was taken two days before the next to last debate with Douglas in Quincy, Illinois.[30] | |

|

1859 (?) | unknown | Springfield, Illinois | unknown | unknown | Photograph, of unknown origin, shows Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, probably in 1859.[31] |

|

October 4, 1859 | Samuel M. Fassett[32] | Chicago, Illinois | Photograph | Negative destroyed in Great Chicago Fire[33] | Lincoln sat for this portrait at the gallery of Cooke and Fassett in Chicago. Cooke wrote in 1865 "Mrs. Lincoln pronounced [it] the best likeness she had ever seen of her husband."[33] |

|

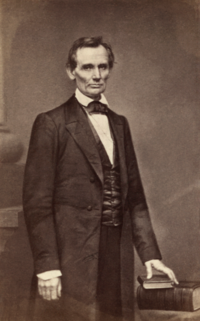

February 27, 1860 | Mathew Brady[34] | New York, New York | Carte-de-visite printed by Brady's gallery from a lost copy negative of a retouched original print | Library of Congress | Mathew Brady's first photograph of Lincoln, on the day of the Cooper Union speech. Over the following weeks, newspapers and magazines gave full accounts of the event, noting the high spirits of the crowd and the stirring rhetoric of the speaker. Artists for Harper's Weekly converted Brady's photograph to a full-page woodcut portrait to illustrate their story of Lincoln's triumph, and in October 1860, Leslie's Weekly used the same image to illustrate a story about the election. Brady himself sold many carte-de-visite photographs of the Illinois politician who had captured the eye of the nation. Brady remembered that he drew Lincoln's collar up high to improve his appearance; subsequent versions of this famous portrait also show that artists smoothed Lincoln's hair, smoothed facial lines and straightened his subject's "roving" left eye. After Lincoln secured the Republican nomination and the presidency, he gave credit to his Cooper Union speech and this portrait, saying, "Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President."[35] |

|

1860 (Spring or Summer) | unknown | Illinois (?) | unknown | Contemporary albumen print believed to be the only surviving likeness printed from the lost original negative made by an unknown photographer, probably in Springfield or Chicago, during the spring or summer of 1860.[36] | |

|

May 9, 1860 | Edward A. Barnwell | Decatur, Illinois | Positive printed on glass from a lost original negative or ambrotype[37] | Decatur Public Library | Abraham Lincoln was in Decatur to attend the Illinois State Republican Convention. Local photographer Edward A. Barnwell wanted to take a picture of "the biggest man" at the convention and invited Lincoln to his People's Ambrotype Gallery at 24 North Water Street to pose for this portrait. The next day, after Richard Oglesby introduced the "Rail Splitter", convention delegates unanimously endorsed Lincoln for President. On May 18 the National Republican Convention meeting in Chicago nominated him as the party's candidate.[38] |

|

May 20, 1860 | William Marsh[39] | Springfield, Illinois | Gelatin silver print copy from the original ambrotype | Library of Congress | Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois, two days after he won his party's nomination.[40] |

|

William Marsh[41] | Salt print from glass negative[42] | Metropolitan Museum of Art | One of five photographs taken by William Marsh for Marcus Lawrence Ward. Although many in the East had read Lincoln's impassioned speeches, few had actually seen the Representative from Illinois.[40] | ||

|

June 3, 1860 | Alexander Hesler[43] | Photograph | Library of Congress | Hesler took a total of four portraits at this sitting. Lincoln's law partner William Herndon wrote of this picture: "There is the peculiar curve of the lower lip, the lone mole on the right cheek, and a pose of the head so essentially Lincolnian; no other artist has ever caught it."[44] | |

|

Alexander Hesler[45] | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | When Lincoln saw this photograph, along with his side view portrait from the same sitting, he remarked "That looks better and expresses me better than any I have ever seen; if it pleases the people I am satisfied."[46] | |||

|

Alexander Hesler[47] | Library of Congress | Lincoln and a Chicago reporter were looking at what is believed to this photo at Lincoln's home shortly after his nomination for president, when he observed "That picture gives a very fair representation of my homely face."[48] | |||

|

June 1860[49] | unknown | Halftone print, from an albumen print from the lost original negative.[50] | unknown | In the summer of 1860 Mr. M. C. Tuttle, a photographer of St. Paul, wrote to Mr. Lincoln, requesting that he have a negative taken and sent to him for local use in the campaign. The request was granted, but the negative was broken in transit. On learning of the accident, Mr. Lincoln sat again, and with the second negative he sent a jocular note wherein he referred to the fact, disclosed by the picture, that in the interval he had "got a new coat". A few copies of the picture were made by Mr. Tuttle, and distributed among the Republican editors of the State.[51] | |

|

1860 (summer) | William Seavey[52] | Photograph | After this single print was made, the negative was lost when a fire destroyed the photographer's gallery.[53] | ||

|

1860 (spring or summer)[54] | unknown | Contemporary albumen print believed to be the only surviving likeness printed from the lost original negative[55] | Library of Congress | A study of Lincoln's powerful physique, this full-length photograph as taken for use by sculptor Henry Kirke Brown, and was found among his effects in 1931.[56] | |

|

1860 (spring or summer)[57] | William Shaw | Chicago or Springfield, Illinois | Albumen print from a lost contemporary negative | Chicago Sun-Times Archives | This image has been heavily retouched at some point. Lincoln's neck, skin and cheek lines are smoothed out, and the bag under the right eye has been diminished.[58] |

|

1860 (summer)[59] | unknown | Springfield, Illinois (?) | Halftone of an albumen print from a lost original negative | Allegheny College | A copy of this image turned up with the effects of artist John Henry Brown, whose watercolor miniature of Lincoln hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.[60] |

|

August 13, 1860[61] | Preston Butler | Springfield, Illinois | Ambrotype plate 5.75 x 4.5 inches | Library of Congress | The last beardless photograph of Lincoln.[62] John M. Read commissioned Philadelphia artist John Henry Brown to paint a good-looking miniature of Lincoln "whether or not the subject justified it". This ambrotype is one of six taken on Monday, August 13, 1860, in Butler's daguerreotype studio (of which only two survive), made for the portrait painter.[63] |

|

November 25, 1860[64] | Samuel G. Altschuler | Chicago, Illinois | Gelatin silver print of a carte-de-visite print of what appears to have been a retouched contemporary albumen print supposedly from the lost original negative[65] | An 11-year-old girl named Grace Bedell wrote to Lincoln, asking "let your whiskers grow ... you would look a great deal better for your face is so thin. All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be President." and the president-elect responded "As to the whiskers have never worn any do you not think people would call it a silly affection if I were to begin it now?" Regardless, the next time he visited his barber William Florville, he announced "Billy, let's give them a chance to grow."[66] By the time he began his inaugural journey by train from Illinois to Washington, D.C., he had a full beard. | |

|

January 1861 | Christopher S. German | Springfield, Illinois | unknown | unknown | |

|

February 9, 1861 | Photograph[67] | Library of Congress | This photograph was taken two days before he left Springfield en route to Washington, DC, for his inauguration.[65] | ||

|

Tintype from lost negative[68] | Private collection | Taken during the same sitting, this profile reveals the back of Lincoln's head more than perhaps any other portrait.[69] | |||

|

February 24, 1861 | Alexander Gardner[70] | Washington, D.C. | Albumen silver print[71] | J. Paul Getty Museum | Taken during President-elect Lincoln's first sitting in Washington, D.C., the day after his arrival by train.[72] |

|

March 1, 1861 and June 30, 1861 (between) | unknown | unknown | Salt print from the lost original negative[73] | Christie's | The first photographic image of the new president. Remarkably, it is not known where or by whom this portrait was taken; the few known examples carry imprints of several different photographers: C.D Fredericks & Co. of New York; W.L. Germon and James E. McLees, both of Philadelphia. This example has been termed "the most valuable Lincoln photo in existence" and sold at auction in 2009 for $206,500.[74] |

|

April 6, 1861[75] | Mathew Brady[76] | Washington, D.C. | Giant imperial photograph from original collodion plate[77] | Library of Congress | Lincoln's drooping left eyelid is clearly visible in this image. |

|

May 16, 1861[78] | Mathew Brady[79] | Solio print of a lost contemporary albumen print from the lost defective original negative made by an unknown photographer at Mathew Brady's gallery,[80] | Brown Digital Repository | Abraham Lincoln, half-length portrait, seated[81] | |

|

May 16, 1861[82] | Mathew Brady[83] | Carte-de-visite printed from one frame of the lost original multiple-image stereographic negative[84] | Library of Congress | President Abraham Lincoln, seated next to small table, in a reflective pose, May 16, 1861, with his hat visible on the table.[85] | |

|

February 1862 | Mathew Brady | Carte-de-visite | Private collection | Taken soon after the death of Lincoln's son Willie. Governor Joseph W. Fifer of Illinois, after seeing this image, commented "The melancholy seemed to roll from his shoulders and drip from the ends of his fingers."[86] | |

|

October 3, 1862 | Alexander Gardner[87] | Antietam, Maryland | Library of Congress | Lincoln decided to visit the front after General McClellan hesitated to attack Robert E. Lee. This picture of Lincoln with McClellan and his officers was taken the morning after the President arrived in Antietam.[88] | |

|

Alexander Gardner | Digital file from original wet collodion glass negative | Lincoln in McClellan's tent after the Battle of Antietam. | |||

|

Alexander Gardner[89] | Cropped digital file from original wet collodion glass negative | Lincoln with Allan Pinkerton and Major General John A. McClernand at Antietam.[90] The photograph was taken in front of the headquarters tent of the U.S. Secret Service.[91] | |||

|

Alexander Gardner[92] | Cropped digital file from original wet collodion glass negative | Lincoln with Allan Pinkerton and Major General John A. McClernand at Antietam.[93] | |||

|

April 17, 1863 | Thomas Le Mere | Washington, D.C. | Carte de Visite | National Portrait Gallery | Mathew Brady Studios' photograph operator, Thomas Le Mere, thought it would be a "considerable call" to capture a full-length portrait of the President. He did so in this instance with a multiple lens camera in Brady's Gallery.[94] |

|

1863 | Lewis Emory Walker[95] | Collodion glass negative | Library of Congress | Lincoln, seated, with an unbuttoned coat and wearing his standard gold watch chain, presented to him in 1863 by a California delegation.[96] | |

|

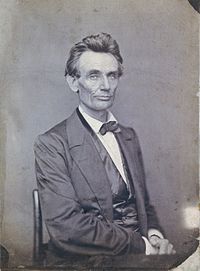

August 9, 1863 | Alexander Gardner[97] | Mammoth-size albumen portrait from original negative | Christie's Auction, Sale 2272, Lot 86 | Lincoln's "Photographer's Face". Per Dr. James Miner, "His large bony face when in repose was unspeakably sad and as unreadable as that of a sphinx, his eyes were as expressionless as those of a dead fish; but when he smiled or laughed at one of his own stories or that of another then everything about him changed; his figure became alert, a lightning change came over his countenance, his eyes scintillated and I thought he had the most expressive features I had ever seen on the face of a man."[98] | |

|

Alexander Gardner[99] | Gelatin Silver Print from glass negative | Metropolitan Museum of Art | This is one of a series of six pictures of the President taken by Alexander Gardner on the day before the official opening of his gallery. Lincoln had promised to be Gardner's first sitter and chose Sunday for his visit to avoid "curiosity seekers and other seekers" while on his way to the gallery. | ||

|

Alexander Gardner | Carte de Visite | Heritage Auctions Lot #43062 | Lincoln holds a newspaper in one hand and his eyeglasses in the other in this autographed Carte de Visite. | ||

|

August 9, 1863[100] | Heritage Auctions Lot #43025 | Lincoln seated with hands in lap. | |||

|

August 9, 1863 | Photograph on paper | Skinner's Auction 2658B, Lot 35 | This image from Lincoln's August 1863 sitting with Alexander Gardner in his new studio at 7th and D Street remained in the family of Lincoln's Secretary John Hay until being sold at auction in 2013.[101] | ||

|

November 8, 1863 | Alexander Gardner[102] | Matte collodion print | Mead Art Museum | This famous image of Lincoln was photographed by Alexander Gardner on November 8, 1863, just weeks before he would deliver the Gettysburg Address. It is sometimes referred to as the "Gettysburg portrait", although it was actually taken in Washington. As Lincoln had previously done in August 1863, he visited Gardner's studio on a Sunday afternoon. He posed for several additional portraits during this session. | |

|

Alexander Gardner | Meserve-Kunhardt Foundation | Profile image | |||

|

Alexander Gardner[103] | Imperial albumen print | Sotheby's, New York, 5 October 2011, N08775, Lot 43 | This image emphasizes Lincoln's large, lanky legs.[104] | ||

|

November 8, 1863 | Alexander Gardner[103] | Lincoln with his two secretaries, John Nicolay (left) and John Hay (right) | |||

|

January 8, 1864[105] | Mathew Brady | Reproduced from a positive printed on film from a contemporary negative[106] | National Archives | Lincoln visited Mathew Brady's studio in Washington, D.C., on at least three occasions in 1864. Several portraits survive from each session. | |

|

January 8, 1864[107] | Overlay of three stereo images from a multiple image stereographic plate | This image is an overlay of three views compiled from a multiple image stereographic plate taken by Brady. | |||

|

February 9, 1864[108] | Anthony Berger | Photograph | Library of Congress | "The Penny Profile". Berger was the manager of Mathew Brady's Gallery when he took multiple photographs at this Tuesday sitting. In 1909 Victor David Brenner used this image and one other similar image from this sitting to model the Lincoln cent.[109] | |

|

February 9, 1864[110] | Carte de Visite | Heritage Auction #43032 | A rare collodion plate of this image in full is housed in the National Archives | ||

|

February 9, 1864 | Imperial albumen print | Heritage Auction #43034 | In 1895 Robert Todd Lincoln wrote "I have always thought the Brady photograph of my father, of which I attach a copy, to be the most satisfactory likeness of him."[111] | ||

|

February 9, 1864[108] | Photograph | National Archives | An original cracked plate, just under the size known as "imperial".[112] The Lincoln portrait on the current United States five-dollar bill is based on this photograph. | ||

|

February 9, 1864 | Anthony Berger (?) | National Archives | Abraham Lincoln with his youngest son Tad. Presumably taken at the same session as the four images just above. | ||

|

February 1865 | Lewis Emory Walker[113] | Washington, D.C.[114] | Albumen silver print | Library of Congress | The short haircut was perhaps suggested by Lincoln's barber to facilitate the taking of his life mask by Clark Mills. Lincoln knew from experience how long hair could cling to plaster. From an 1865 stereograph long attributed to Mathew Brady, was actually taken by Lewis Emory Walker, a government photographer, about February 1865 and published for him by the E. & H. T. Anthony Co., of New York.[115] |

|

February 5, 1865 | Alexander Gardner[116] | Washington, D.C. | J. Paul Getty Museum | Abraham Lincoln with his youngest son Tad, taken ten weeks before the President was assassinated. | |

|

Alexander Gardner[117] | Gelatin silver print of a carte-de-visite printed from one frame of the lost original multiple-image stereographic negative.[118] | Library of Congress | See below. | ||

|

Alexander Gardner[119] | See below. | ||||

|

Alexander Gardner[120] | Gelatin silver print of a lost period print of the multiple-image stereographic pose[121] | This photograph of Lincoln was made when the burden of the presidency had taken its toll. President Lincoln visited Gardner's studio one Sunday in February 1865, the final year of the Civil War, accompanied by the American portraitist Matthew Wilson. Wilson had been commissioned to paint the president's portrait, but because Lincoln could spare so little time to pose, the artist needed recent photographs to work from. The pictures served their purpose, but the resulting painting- a traditional, formal, bust-length portrait in an oval format—is not particularly distinguished and hardly remembered today. Gardner's surprisingly candid photographs have proven more enduring, even though they were not originally intended to stand alone as works of art.[122] | |||

|

Alexander Gardner[123] | Only surviving print from a glass negative that was accidentally cracked during processing and thrown away[124] | National Portrait Gallery | According to Frank Goodyear, the National Portrait Gallery's photo curator, "This is the last formal portrait of Abraham Lincoln before his assassination. I really like it because Lincoln has a hint of a smile. The inauguration is a couple of weeks away; he can understand that the war is coming to an end; and here he permits, for one of the first times during his presidency, a hint of better days tomorrow."[124] | ||

|

March 4, 1865 | Alexander Gardner | 1 photographic print: albumen silver | Library of Congress | Cropped portion of Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address, which is the only known photograph of the event. Lincoln stands in the center, with papers in his hand, on the east front of the United States Capitol. | |

|

March 6, 1865 | Henry F. Warren | The last known high-quality photograph of Lincoln alive, on a balcony at the White House. Two other poses were taken, another sitting pose and a standing pose, none of which survive. Besides this print, no other negatives or prints survive from this shoot. |

See also Wikipedia article on Tad Lincoln for the famous 1864 photograph of Abraham Lincoln with his son Tad, by Anthony Berger.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nicolay, John G. (1891). "Lincoln's Personal Appearance". The Century. 42: 933. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Sotos, image A46 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Library of Congress exhibit Archived 2013-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burton Archived 2013-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, 2008

- ^ Sotos, image A54j Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tarbell 1896, page n19 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A57bzb Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Tarbell 1896, page 49 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A57 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fraker 2012, Page 44

- ^ Sotos, image A58x3 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Christie's Sale 1685, Lot 82

- ^ Sotos, image A58x4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ostendorf 1998, page 27

- ^ a b Ostendorf 1998, page 25

- ^ Meserve, Frederick Hill (1915). Lincolniana : historical portraits and views. New York. p. 25. OCLC 4600116. Archived from the original on 2016-11-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sotos, image A58eg1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tarbell 1896, page 41 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A58dy Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Tarbell 1896, page 113 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A58x1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lincoln, July 17, 1858

- ^ Sotos, image A58hz Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tarbell 1896, page 65 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A58i Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tarbell 1896, page 215 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A58ja Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lincoln by Thomson

- ^ Sotos, image A58jk Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fisher 1968

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, page 31

- ^ Sotos, image A59jd Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ostendorf 1998, page 30

- ^ Sotos, image A60bza Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, pages 35–36

- ^ Sotos, image A60x2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A60ei Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spates 2008

- ^ Sotos, image A60et1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ostendorf 1998, p. 42

- ^ Sotos, image A60et2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Sotos, image A60fc1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, page 46

- ^ Sotos, image A60fc2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, page 47

- ^ Sotos, image A60fc4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, page 48

- ^ Sotos, image A60x5 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p62

- ^ Tarbell 1896, page 193 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A60x1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, page 53

- ^ Sotos, image A60x4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p61

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p17

- ^ Sotos, image A60x6 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p66

- ^ Sotos, image A60x3 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p54

- ^ Sotos, image A60hm1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p66

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p62

- ^ Sotos, image A60ky Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Mellon 1979, p83

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p67

- ^ Sotos, image A61bi1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A61bi2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p71

- ^ Sotos, image A61bx1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ President Abraham Lincoln, Washington D.C.

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p77

- ^ Sotos, image A61x1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Christie's Sale 2265, Lot 19

- ^ Library of Congress LC-USZ62-112729 Archived 2014-11-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A61y1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p93

- ^ Library of Congress LC-USZ62-13429 Archived 2016-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A61qq3 Archived 2016-04-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p98

- ^ Library of Congress LC-USZ62-13429

- ^ Library of Congress LC-USZ62-15178 Archived 2013-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A61y4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p101

- ^ Library of Congress LC-USZ62-15178

- ^ Ostendorf 1998

- ^ Sotos, image A62jc1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p106

- ^ Sotos, image A62jc3 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p109,117

- ^ Zeller 2005, page xvi

- ^ Sotos, image A62jc2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p108,117

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p129

- ^ Sotos, image A63 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p160

- ^ Sotos, image A63hi5 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p139

- ^ Sotos, image A63h1 Archived 2015-03-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p136

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p360

- ^ Sotos, image A63kh2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Sotos, image A63kh4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostndorf 1998, p149

- ^ Sotos, image A64ah2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p156

- ^ Sotos, image A64ah4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Sotos, image A64bi2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p174

- ^ Sotos, image A64b3 Archived 2016-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p176

- ^ Ostendorf 1998, p178

- ^ Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-18958

- ^ Sotos, image A64y1 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ostendorf 1998 p198-9

- ^ Ostendorf 1998 p218-20

- ^ Sotos, image A65b4 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p173

- ^ Sotos, image A65b2 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sotos, image A65b3 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mellon 1979, p185

- ^ Abraham Lincoln, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005

- ^ Sotos, image A65b5 Archived 2015-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Norris 2011

References

[edit]- Sotos, John G. "The Physical Lincoln Wiki".

- Burton, Vernon. "Lincoln Remembered". University of Illinois. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Tarbell, Ida M; Davis, John McCan (1896). The early life of Abraham Lincoln. New York: S. S. McClure.

- "Christie's Sale 1685, Lot 82". 2005. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012.

- Lincoln, Abraham (July 17, 1858). Speech of Hon. Abraham Lincoln: delivered in Springfield, Saturday evening, July 17, 1858 (Speech). Springfield, Il.

- Fraker, Guy C. (2012). Lincoln's Ladder to the Presidency: The Eighth Judicial Circuit. SIU Press. ISBN 9780809332021.

- "Lincoln by Thomson". National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Fisher, LeRoy (Autumn 1968). "Lincoln's 1858 Visit to Pittsfield, Illinois". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 61 (3): 350–364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-28. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Ostendorf, Lloyd (1998). Lincoln Photographs: A Complete Album. Dayton, OH: Rockywood Press. ISBN 0890290873.

- Spates, Alicia (9 Feb 2008). "Copies of Barnwell's Lincoln photo made available through library, Millikin partnership". Herald-Review. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Abraham Lincoln". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2005. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Mellon, James (1979). The Face of Lincoln. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0670304332.

- "Christie's Sale 2265, Lot 19". 2009. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Alt URL

- "LC-USZ62-15178". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- "LC-USZ62-112729". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. 1861. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- "Abraham Lincoln, February 5, 1865" (PDF). National Endowment for the Humanities. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-10-27. Retrieved 2013-03-23.

- "LC-DIG-ppmsca-18958". Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. 1865. Retrieved 2013-03-24.

- Zeller, Bob (2005). The Blue and Gray in Black and White: A History of Civil War Photography. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0275982432.

- Norris, Michele (2011-12-05). "'The Atlantic' Remembers Its Civil War Stories". NPR. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "President Abraham Lincoln, Washington D.C." J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 16 March 2014.