Kerr–Newman metric

| General relativity |

|---|

|

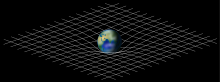

The Kerr–Newman metric describes the spacetime geometry around a mass which is electrically charged and rotating. It is a vacuum solution which generalizes the Kerr metric (which describes an uncharged, rotating mass) by additionally taking into account the energy of an electromagnetic field, making it the most general asymptotically flat and stationary solution of the Einstein–Maxwell equations in general relativity. As an electrovacuum solution, it only includes those charges associated with the magnetic field; it does not include any free electric charges.

Because observed astronomical objects do not possess an appreciable net electric charge[citation needed] (the magnetic fields of stars arise through other processes), the Kerr–Newman metric is primarily of theoretical interest. The model lacks description of infalling baryonic matter, light (null dusts) or dark matter, and thus provides an incomplete description of stellar mass black holes and active galactic nuclei. The solution however is of mathematical interest and provides a fairly simple cornerstone for further exploration.[citation needed]

The Kerr–Newman solution is a special case of more general exact solutions of the Einstein–Maxwell equations with non-zero cosmological constant.[1]

History

[edit]In December of 1963, Roy Kerr and Alfred Schild found the Kerr–Schild metrics that gave all Einstein spaces that are exact linear perturbations of Minkowski space. In early 1964, Kerr looked for all Einstein–Maxwell spaces with this same property. By February of 1964, the special case where the Kerr–Schild spaces were charged (including the Kerr–Newman solution) was known but the general case where the special directions were not geodesics of the underlying Minkowski space proved very difficult. The problem was given to George Debney to try to solve but was given up by March 1964. About this time Ezra T. Newman found the solution for charged Kerr by guesswork. In 1965, Ezra "Ted" Newman found the axisymmetric solution of Einstein's field equation for a black hole which is both rotating and electrically charged.[2][3] This formula for the metric tensor is called the Kerr–Newman metric. It is a generalisation of the Kerr metric for an uncharged spinning point-mass, which had been discovered by Roy Kerr two years earlier.[4]

Four related solutions may be summarized by the following table:

Non-rotating (J = 0) Rotating (J ∈ ) Uncharged (Q = 0) Schwarzschild Kerr Charged (Q ∈ ) Reissner–Nordström Kerr-Newman

where Q represents the body's electric charge and J represents its spin angular momentum.

Overview of the solution

[edit]Newman's result represents the simplest stationary, axisymmetric, asymptotically flat solution of Einstein's equations in the presence of an electromagnetic field in four dimensions. It is sometimes referred to as an "electrovacuum" solution of Einstein's equations.

Any Kerr–Newman source has its rotation axis aligned with its magnetic axis.[5] Thus, a Kerr–Newman source is different from commonly observed astronomical bodies, for which there is a substantial angle between the rotation axis and the magnetic moment.[6] Specifically, neither the Sun, nor any of the planets in the Solar System have magnetic fields aligned with the spin axis. Thus, while the Kerr solution describes the gravitational field of the Sun and planets, the magnetic fields arise by a different process.

If the Kerr–Newman potential is considered as a model for a classical electron, it predicts an electron having not just a magnetic dipole moment, but also other multipole moments, such as an electric quadrupole moment.[7] An electron quadrupole moment has not yet been experimentally detected; it appears to be zero.[7]

In the G = 0 limit, the electromagnetic fields are those of a charged rotating disk inside a ring where the fields are infinite. The total field energy for this disk is infinite, and so this G = 0 limit does not solve the problem of infinite self-energy.[8]

Like the Kerr metric for an uncharged rotating mass, the Kerr–Newman interior solution exists mathematically but is probably not representative of the actual metric of a physically realistic rotating black hole due to issues with the stability of the Cauchy horizon, due to mass inflation driven by infalling matter. Although it represents a generalization of the Kerr metric, it is not considered as very important for astrophysical purposes, since one does not expect that realistic black holes have a significant electric charge (they are expected to have a minuscule positive charge, but only because the proton has a much larger momentum than the electron, and is thus more likely to overcome electrostatic repulsion and be carried by momentum across the horizon).

The Kerr–Newman metric defines a black hole with an event horizon only when the combined charge and angular momentum are sufficiently small:[9]

An electron's angular momentum J and charge Q (suitably specified in geometrized units) both exceed its mass M, in which case the metric has no event horizon. Thus, there can be no such thing as a black hole electron — only a naked spinning ring singularity.[10] Such a metric has several seemingly unphysical properties, such as the ring's violation of the cosmic censorship hypothesis, and also appearance of causality-violating closed timelike curves in the immediate vicinity of the ring.[11]

A 2009 paper by Russian theorist Alexander Burinskii considered an electron as a generalization of the previous models by Israel (1970)[12] and Lopez (1984),[13] which truncated the "negative" sheet of the Kerr-Newman metric, obtaining the source of the Kerr-Newman solution in the form of a relativistically rotating disk. Lopez's truncation regularized the Kerr-Newman metric by a cutoff at :, replacing the singularity by a flat regular space-time, the so called "bubble". Assuming that the Lopez bubble corresponds to a phase transition similar to the Higgs symmetry breaking mechanism, Burinskii showed that a gravity-created ring singularity forms by regularization the superconducting core of the electron model [14] and should be described by the supersymmetric Landau-Ginzburg field model of phase transition:

By omitting Burinsky's intermediate work, we come to the recent new proposal: to consider the truncated by Israel and Lopez negative sheet of the KN solution as the sheet of the positron.[15]

This modification unites the KN solution with the model of QED, and shows the important role of the Wilson lines formed by frame-dragging of the vector potential.

As a result, the modified KN solution acquires a strong interaction with Kerr's gravity caused by the additional energy contribution of the electron-positron vacuum and creates the Kerr–Newman relativistic circular string of Compton size.

Limiting cases

[edit]The Kerr–Newman metric can be seen to reduce to other exact solutions in general relativity in limiting cases. It reduces to

- the Kerr metric as the charge Q goes to zero;

- the Reissner–Nordström metric as the angular momentum J (or a = J/M ) goes to zero;

- the Schwarzschild metric as both the charge Q and the angular momentum J (or a) are taken to zero; and

- Minkowski space if the mass M, the charge Q, and the rotational parameter a are all zero.

Alternately, if gravity is intended to be removed, Minkowski space arises if the gravitational constant G is zero, without taking the mass and charge to zero. In this case, the electric and magnetic fields are more complicated than simply the fields of a charged magnetic dipole; the zero-gravity limit is not trivial.[citation needed]

The metric

[edit]The Kerr–Newman metric describes the geometry of spacetime for a rotating charged black hole with mass M, charge Q and angular momentum J. The formula for this metric depends upon what coordinates or coordinate conditions are selected. Two forms are given below: Boyer–Lindquist coordinates, and Kerr–Schild coordinates. The gravitational metric alone is not sufficient to determine a solution to the Einstein field equations; the electromagnetic stress tensor must be given as well. Both are provided in each section.

Boyer–Lindquist coordinates

[edit]One way to express this metric is by writing down its line element in a particular set of spherical coordinates,[16] also called Boyer–Lindquist coordinates:

where the coordinates (r, θ, ϕ) are standard spherical coordinate system, and the length scales:

have been introduced for brevity. Here rs is the Schwarzschild radius of the massive body, which is related to its total mass-equivalent M by

where G is the gravitational constant, and rQ is a length scale corresponding to the electric charge Q of the mass

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity.

Electromagnetic field tensor in Boyer–Lindquist form

[edit]The electromagnetic potential in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates is[17][18]

while the Maxwell tensor is defined by

In combination with the Christoffel symbols the second order equations of motion can be derived with

where is the charge per mass of the test particle.

Kerr–Schild coordinates

[edit]The Kerr–Newman metric can be expressed in the Kerr–Schild form, using a particular set of Cartesian coordinates, proposed by Kerr and Schild in 1965. The metric is as follows.[19][20][21]

Notice that k is a unit vector. Here M is the constant mass of the spinning object, Q is the constant charge of the spinning object, η is the Minkowski metric, and a = J/M is a constant rotational parameter of the spinning object. It is understood that the vector is directed along the positive z-axis, i.e. . The quantity r is not the radius, but rather is implicitly defined by the relation

Notice that the quantity r becomes the usual radius R

when the rotational parameter a approaches zero. In this form of solution, units are selected so that the speed of light is unity (c = 1). In order to provide a complete solution of the Einstein–Maxwell equations, the Kerr–Newman solution not only includes a formula for the metric tensor, but also a formula for the electromagnetic potential:[19][22]

At large distances from the source (R ≫ a), these equations reduce to the Reissner–Nordström metric with:

In the Kerr–Schild form of the Kerr–Newman metric, the determinant of the metric tensor is everywhere equal to negative one, even near the source.[1]

Electromagnetic fields in Kerr–Schild form

[edit]The electric and magnetic fields can be obtained in the usual way by differentiating the four-potential to obtain the electromagnetic field strength tensor. It will be convenient to switch over to three-dimensional vector notation.

The static electric and magnetic fields are derived from the vector potential and the scalar potential like this:

Using the Kerr–Newman formula for the four-potential in the Kerr–Schild form, in the limit of the mass going to zero, yields the following concise complex formula for the fields:[23]

The quantity omega () in this last equation is similar to the Coulomb potential, except that the radius vector is shifted by an imaginary amount. This complex potential was discussed as early as the nineteenth century, by the French mathematician Paul Émile Appell.[24]

Irreducible mass

[edit]The total mass-equivalent M, which contains the electric field-energy and the rotational energy, and the irreducible mass Mirr are related by[25][26]

which can be inverted to obtain

In order to electrically charge and/or spin a neutral and static body, energy has to be applied to the system. Due to the mass–energy equivalence, this energy also has a mass-equivalent; therefore M is always higher than Mirr. If for example the rotational energy of a black hole is extracted via the Penrose processes,[27][28] the remaining mass–energy will always stay greater than or equal to Mirr.

Important surfaces

[edit]

Setting to 0 and solving for gives the inner and outer event horizon, which is located at the Boyer–Lindquist coordinate

Repeating this step with gives the inner and outer ergosphere

Equations of motion

[edit]For brevity, we further use nondimensionalized quantities normalized against , , and , where reduces to and to , and the equations of motion for a test particle of charge become[29][30]

with for the total energy and for the axial angular momentum. is the Carter constant:

where is the poloidial component of the test particle's angular momentum, and the orbital inclination angle.

and

with and for particles are also conserved quantities.

is the frame dragging induced angular velocity. The shorthand term is defined by

The relation between the coordinate derivatives and the local 3-velocity is

for the radial,

for the poloidial,

for the axial and

for the total local velocity, where

is the axial radius of gyration (local circumference divided by 2π), and

the gravitational time dilation component. The local radial escape velocity for a neutral particle is therefore

References

[edit]- ^ a b Stephani, Hans; Kramer, Dietrich; MacCallum, Malcolm; Hoenselaers, Cornelius; Herlt, Eduard (2009-09-24). Exact Solutions of Einstein's Field Equations. Cambridge University Press. p. 485. ISBN 978-1-139-43502-4. See page 485 regarding determinant of metric tensor. See page 325 regarding generalizations.

- ^ Newman, Ezra; Janis, Allen (1965). "Note on the Kerr Spinning-Particle Metric". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 6 (6): 915–917. Bibcode:1965JMP.....6..915N. doi:10.1063/1.1704350.

- ^ Newman, Ezra; Couch, E.; Chinnapared, K.; Exton, A.; Prakash, A.; Torrence, R. (1965). "Metric of a Rotating, Charged Mass". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 6 (6): 918–919. Bibcode:1965JMP.....6..918N. doi:10.1063/1.1704351.

- ^ Kerr, RP (1963). "Gravitational field of a spinning mass as an example of algebraically special metrics". Physical Review Letters. 11 (5): 237–238. Bibcode:1963PhRvL..11..237K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.11.237.

- ^ Punsly, Brian (10 May 1998). "High-energy gamma-ray emission from galactic Kerr–Newman black holes. I. The central engine". The Astrophysical Journal. 498 (2): 646. Bibcode:1998ApJ...498..640P. doi:10.1086/305561.

All Kerr–Newman black holes have their rotation axis and magnetic axis aligned; they cannot pulse.

- ^ Lang, Kenneth (2003). The Cambridge Guide to the Solar System. Cambridge University Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780521813068 – via Internet Archive.

magnetic dipole moment and axis and the sun.

- ^ a b Rosquist, Kjell (2006). "Gravitationally induced electromagnetism at the Compton scale". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 23 (9): 3111–3122. arXiv:gr-qc/0412064. Bibcode:2006CQGra..23.3111R. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/23/9/021. S2CID 15285753.

- ^ Lynden-Bell, D. (2004). "Electromagnetic magic: The relativistically rotating disk". Physical Review D. 70 (10): 105017. arXiv:gr-qc/0410109. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..70j5017L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.70.105017. S2CID 119091075.

- ^ Meinel, Reinhard (29 October 2015). "A Physical Derivation of the Kerr–Newman Black Hole Solution". In Nicolini P.; Kaminski M.; Mureika J.; Bleicher M. (eds.). 1st Karl Schwarzschild Meeting on Gravitational Physics. Springer Proceedings in Physics. Vol. 170. pp. 53–61. arXiv:1310.0640. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20046-0_6. ISBN 978-3-319-20045-3. S2CID 119200468.

- ^ Burinskii, Alexander (2008). "The Dirac–Kerr electron". Gravitation and Cosmology. 14: 109–122. arXiv:hep-th/0507109. doi:10.1134/S0202289308020011. S2CID 119084073.

- ^ Carter, Brandon (1968). "Global structure of the Kerr family of gravitational fields". Physical Review. 174 (5): 1559. Bibcode:1968PhRv..174.1559C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.174.1559.

- ^ Israel, Werner (1970). "Source of the Kerr metric". Physical Review D. 2 (4): 641. Bibcode:1970PhRvD...2..641I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.2.641.

- ^ Lopez, Carlos (1984). "Extended model of the electron in general relativity". Physical Review D. 30 (2): 313. Bibcode:1984PhRvD..30..313L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.30.313.

- ^ Burinskii, Alexander (2009). "Superconducting Source of the Kerr-Newman Electron". arXiv:0910.5388 [hep-th].

- ^ Burinskii, Alexander (2022). "Gravitating Electron Based on Overrotating Kerr-Newman Solution". Universe. 8 (11): 553. Bibcode:2022Univ....8..553B. doi:10.3390/universe8110553.

- ^ Hájíček, P.; Meyer, Frank; Metzger, Jan (2008). An introduction to the relativistic theory of gravitation. Lecture notes in physics. Berlin: Springer. p. 243. ISBN 978-3-540-78658-0. OCLC 221218012.

- ^ Carter, Brandon (1968-10-25). "Global Structure of the Kerr Family of Gravitational Fields" (PDF). Physical Review. 174 (5): 1559–1571. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.174.1559.

- ^ Luongo, Orlando; Quevedo, Hernando (2014). "Characterizing repulsive gravity with curvature eigenvalues". Physical Review D. 90 (8): 084032. arXiv:1407.1530. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..90h4032L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.084032. S2CID 118457584.

- ^ a b Debney, G. C.; Kerr, R. P.; Schild, A. (1969). "Solutions of the Einstein and Einstein-Maxwell Equations". Journal of Mathematical Physics. 10 (10): 1842–1854. Bibcode:1969JMP....10.1842D. doi:10.1063/1.1664769. See equations (7.10), (7.11) and (7.14).

- ^ Balasin, Herbert; Nachbagauer, Herbert (1994). "Distributional energy–momentum tensor of the Kerr–Newman spacetime family". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 11 (6): 1453–1461. arXiv:gr-qc/9312028. Bibcode:1994CQGra..11.1453B. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/11/6/010. S2CID 6041750.

- ^ Samuel Berman, Marcelo; et al. (2006). Kreitler, Paul V. (ed.). Trends in black hole research. New York: Nova Science Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-59454-475-0. OCLC 60671837.

- ^ Nieuwenhuizen, Theo M.; Philipp, Walter; Špička, Václav; Mehmani, Bahar; Aghdami, Maryam J.; Khrennikov, Andrei, eds. (2007). Beyond the quantum: proceedings of the Lorentz Workshop "Beyond the Quantum", Lorentz Center Leiden, The Netherlands, 29 May - 2 June 2006. New Jersey NJ: World Scientific. p. 321. ISBN 978-981-277-117-9.

The formula for the vector potential of Burinskii differs from that of Debney et al. merely by a gradient which does not affect the fields.

- ^ Gair, Jonathan. "Boundstates in a Massless Kerr–Newman Potential" Archived 2011-09-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Appell, Math. Ann. xxx (1887) pp. 155–156. Discussed by Whittaker, Edmund and Watson, George. A Course of Modern Analysis, page 400 (Cambridge University Press 1927).

- ^ Thibault Damour: Black Holes: Energetics and Thermodynamics, page 11

- ^ Eq. 57 in Pradhan, Parthapratim (2014). "Black hole interior mass formula". The European Physical Journal C. 74 (5): 2887. arXiv:1310.7126. Bibcode:2014EPJC...74.2887P. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-2887-2. S2CID 46448376.

- ^ Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald; Kaiser, David (2017). Gravitation (PDF). Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. p. 877, 908. ISBN 978-0-691-17779-3. OCLC 1006427790.

- ^ Bhat, Manjiri; Dhurandhar, Sanjeev; Dadhich, Naresh (1985). "Energetics of the Kerr–Newman black hole by the penrose process". Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy. 6 (2): 85–100. Bibcode:1985JApA....6...85B. doi:10.1007/BF02715080. S2CID 53513572.

- ^ Cebeci, Hakan; et al. "Motion of the charged test particles in Kerr–Newman–Taub–NUT spacetime and analytical solutions".

- ^ Hackmann, Eva; Xu, Hongxiao (2013). "Charged particle motion in Kerr–Newmann space–times". Physical Review D. 87 (12): 4. arXiv:1304.2142. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..87l4030H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.87.124030. S2CID 118576540.

Bibliography

[edit]- Wald, Robert M. (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 312–324. ISBN 978-0-226-87032-8.

External links

[edit]- Adamo, Tim; Newman, Ezra (2014). "Kerr–Newman metric". Scholarpedia. 9 (10): 31791. arXiv:1410.6626. Bibcode:2014SchpJ...931791N. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.31791. co-authored by Ezra T. Newman himself

- SR Made Easy, chapter 11: Charged and Rotating Black Holes and Their Thermodynamics

![{\displaystyle f={\frac {Gr^{2}}{r^{4}+a^{2}z^{2}}}\left[2Mr-Q^{2}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a04a917784bc997d802807c0daa7236ddb674cdf)