Journals of the First Fleet

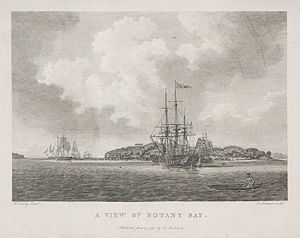

There are 20 known contemporary accounts of the First Fleet made by people sailing in the fleet, including journals (both manuscript and published) and letters.[1][2] The eleven ships of the fleet, carrying over 1,000 convicts, soldiers and seamen, left England on 13 May 1787 and arrived in Botany Bay between 18 and 20 January 1788 before relocating to Port Jackson to establish the first European settlement in Australia, a penal colony which became Sydney.

At least 12 people on the fleet kept a journal of their experiences, some of which were later published, while others wrote letters home during the voyage or soon after their arrival in Australia. These personal accounts of the voyage were made by people including surgeons, officers, soldiers, ordinary seamen, and Captain Arthur Phillip, who commanded the expedition. Only one known account, that of James Martin, was by a transported convict. Their journals document the day-to-day experiences of those in the fleet, and record significant events including the first contact between the British settlers and the Aboriginal people of the area.

In 2009, the manuscript journals were included in The Australian Memory of the World Register, a regional register associated with the UNESCO international Memory of the World programme.[3][4]

Journals

[edit]Arthur Bowes Smyth

[edit]

Arthur Bowes Smyth (1750–1790) was a surgeon on board Lady Penrhyn, the transport that carried female convicts on the First Fleet. Smyth was born on 23 August 1750 at Tolleshunt D'Arcy, Essex, England, and was buried there shortly after his return to England on 31 March 1790.[5][6][7] Son of Surgeon Thomas Smyth and the seventh of ten children, Arthur Bowes Smyth followed in his father's footsteps practising medicine in his place of birth until appointed "Surgeon to the Ship's Company" aboard Lady Penrhyn in 1787.[7][8] Bowes Smyth then took charge of the prisoners on the ship when the convicts' surgeon John Turnpenny Altree fell ill at Tenerife and in Governor Arthur Phillip's opinion had proved unequal to the task.[7][9][10][11]

Bowes, as he was known in the colony, kept a journal from 22 March 1787 to 12 August 1789.[7] The journal is a detailed account of the voyage, recording weather observations, events on board, treatment of the sick and descriptions of ports of call en route in particular Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town.[8] His journal is notable for its interest in natural history including descriptions of bird life at Port Jackson and Lord Howe Island on Lady Penrhyn's return voyage.[6][7] The journal contains 25 drawings in watercolour, pen and ink, including the earliest known surviving illustration of the emu by a European.[5] These elements provide a unique account different from the other First Fleet Journals.

His journal is one of the most detailed eyewitness accounts of the first weeks of European settlement of Australia.[12] The journal entries for 18–26 January record first impressions on arrival including interactions with Aboriginal communities and descriptions of the vegetation, intense heat and native wildlife.[5][6] The convicts and their children who disembarked Lady Penrhyn at Port Jackson are listed.[5] His first journal entry dated 22 March 1787 records the full crew list and the women convicts, their name, age, trade, crime and term of transportation. The list of children born on the voyage contains inaccuracies regarding the sex of the child and dates of birth and death.[13] Lady Penrhyn, under charter to the East India Company to continue her voyage to China for a cargo of tea, departed Port Jackson in early May. His journal continues, recording the return voyage via Lord Howe Island, Tahiti, China, St Helena and finally England.[14][15] The original journal is now in the collection of the National Library of Australia with a manuscript copy in the British Library and a third manuscript copy held by the State Library of New South Wales.[16]

William Bradley

[edit]

William Bradley (1757–1833) was a naval officer who sailed in the First Fleet on HMS Sirius as first lieutenant.[17] Bradley joined the navy in 1772, and served as a captain's servant, able seaman, midshipman, and master's mate, on H.M.S. Lenox, Aldborough, Mermaid, Rippon, Prothée, Phaeton and Ariadne.[17] Bradley's journal is held by the State Library of New South Wales and begins in 1786 with the organisation of the fleet from Deptford to Portsmouth and Gravesend,[18] describing taking convicts, instruments and supplies on board, and lists some names and numbers of those on board HMS Sirius.[19]

The journal records the voyage to Australia and describes ports, ships passed, the weather, as well as difficulties on board such having insufficient provisions to preserve the cattle on board.[19] Upon arriving in Australia, Bradley recounts his impressions of the colony as well as his interest in Aboriginal people and natural history.[20] In 1789 Bradley describes being one of a party ordered by Governor Arthur Phillip to capture two Aborigines, Colebee[21] and Bennelong by force, calling it "by far the most unpleasant service I ever was order'd to Execute."[19] Bradley's journal contains 29 watercolours inserted between the pages,[22] as well as 22 detailed charts illustrating the voyage to Australia, early survey expeditions in the colony, and further voyages on HMS Sirius.[23][24] Two days after reaching Port Jackson, Bradley and John Hunter began to survey and chart Sydney Harbour, naming various landmarks including Bradley's Point (now known as Bradleys Head).[24] The earliest known map of Sydney is Bradley's sketch of the encampment in March 1788.[24]

Bradley's journal also documents his journey to Norfolk Island in March 1790.[20] HMS Sirius was wrecked on arrival,[25] and Bradley remained for 11 months undertaking a survey of the island, then travelled back to Port Jackson on Supply.[20] The journal concludes with the return of HMS Sirius crew to England in April 1792 on Waakzaamheid, anchoring at Portsmouth on 23 April.[18][19]

From 1809, Bradley suffered increasingly from mental disturbances.[17] He was exiled to France after being caught attempting to defraud the postal authorities in 1814, and remained in exile until his death in 1833.[17]

Ralph Clark

[edit]

Ralph Clark (c. 1755–1794) was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, between 1755[26] and 1762[27] and died in the West Indies in 1794. He married Betsy Alicia Trevan in 1784 and their son Ralph Stuart (sic), was born in 1785.[27] He was a Second Lieutenant of Marines with the 6th Company when he served on the convict transport Friendship bound for Botany Bay. He was later promoted to First Lieutenant.[28] The convict transport Friendship was built in Scarborough, England, in 1784 and was 276 tons. It was the smallest of the convict transports and carried 76 male and 21 female convicts with a crew of about 20.[29]

Clark's journal covers the First Fleet voyage and the first few weeks in New South Wales. It is held by the State Library of New South Wales and covers the period from 9 March 1787 to 10 March 1788. It lists all convicts aboard the 'Friendship', including the date when each was received on board, name, trade, crime, sentence, when and where they were tried, county, and place of birth. Clark's journal gives an insight into his view of the convict women who he refers to as "damned whores" and "abandond wreches [sic]".[30] His journal is of a very personal nature and makes constant reference to his 'beloved Betsy' and son Ralph, who he greatly missed.[30] Clark's journal has only three entries for March 1787, and no further entries until 13 May 1787.[28] His complete journal also covers later periods and is in four volumes, which includes his visit to Norfolk Island and his voyage on Gorgon returning to England.[30] The four volumes cover the following time periods: 9 March 1787 – 31 December 1787, 1 January 1788 – 10 March 1788, 15 February 1790 – 2 January 1791, and 25 January 1791 – 17 June 1792.[30] His journal and letterbook have also been published,[28] transcribed and digitised.[30]

David Collins

[edit]David Collins (1756–1810) was born on 3 March 1756 in London and joined the Royal Marines at the age of 14.[31] He was Judge-Advocate for the military and civil courts in the new colony of New South Wales, and later the first lieutenant-governor of the newly established colony Van Diemen's Land.[31] He served on HMS Sirius. Once he arrived in Sydney, Collins worked as secretary to Governor Phillip.[32] From his arrival in Botany Bay with the First Fleet on 20 January 1788 on board HMS Sirius,[33] Collins was responsible for the Colony's entire legal establishment.

During his time on HMS Sirius and in the colony, he kept a journal which also included his experiences in the settlement at Sydney. In 1797 he returned to London and the following year with the help of his wife Maria, he published his journal entitled An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales,[34] a detailed first-hand account of early settlement in Australia.[13] The book's introduction describes the long voyage of the fleet and particularly HMS Sirius to Australia. Collins gives an account of the accompanying ships, their weight and the number of convicts, supplies and crew each carried. He describes an incident on Sunday 20 May 1787, where a mutiny being plotted by some convicts on board Scarborough was discovered. Captain Phillip ordered the two ringleaders be taken on board HMS Sirius, where they were punished with two dozen lashes to each offender.[35] In the introduction Collins also mentions the fleet's passage to Brazil and describes two accidents that took place on that part of the voyage:

Only two accidents happened during the passage to the Brazils. A seaman belonging to the Alexander was so unfortunate as to fall overboard, and could not be recovered – and a female convict on board the Prince of Wales was so much bruised by the falling of the boat from off the booms, (which, owing to the violent motion of the ship, had got loose,) that she died the following day, notwithstanding the professional skill and humane attention of the principal surgeon, for as the boat in launching forward fell upon the neck and crushed the vertebrae and spine, all the aid he could render her was of no avail.

— David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales[35]

The rest of the volume describes life in the early days of the new colony. Collins describes the local Aboriginal people, the Australian environment, events, accidents, crimes, supplies and the weather. It also includes some illustrations and plates.[34] A second volume was published in 1802.[36]

In 1803 he was appointed as lieutenant-governor and commissioned to form a new settlement at Sullivan Bay, Victoria. The location proved to be unsuitable, and Collins received permission to relocate to an existing settlement established at Risdon.[31] He sailed for Van Diemen's Land (now known as Tasmania) on HMS Calcutta. Critical of the intended site at Risdon, Collins chose Sullivans Cove as a superior location and harbour for Hobart Town. He served as Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land until he died in 1810.[31]

John Easty

[edit]

John Easty (fl. 1768?–1793) was a private soldier in the marines. His dates of birth and death are not known. Easty joined the marines no later than January 1784, and was appointed to Captain-Lieutenant Meredith's company on 4 November 1787.[37] He arrived with the First Fleet on Scarborough,[38] the second largest vessel in the First Fleet.[39]

Easty's journal is held by the State Library of New South Wales and he was the lowest ranking author of the surviving journals of the First Fleet.[40] He describes events on the voyage and in the colony in simple, irregular English. Incidents include accidents, crimes and punishments, and encounters with Aboriginal people. In March 1788 he received a flogging for bringing a female convict into the camp.[37] Some of the journal is hearsay or was written later.[37] Most of the events are reported in a matter of fact way, but Easty sometimes expresses his own strong opinions on matters such as the administration of the colony and religious beliefs. On 22 February 1790, he writes that he and a private in the 53rd Regiment, Thomas Brimage, signed and sealed their last wills and testaments to each other.[41]

Easty returned to England on Atlantic in December 1792, with the last detachment of marines to leave Sydney;[37] Arthur Philip also returned home on this voyage.[38] Easty rejoined his division at Portsmouth in May 1793.[37] He left the marines and was employed by Waddington & Smith, grocers, in London in September 1794.[37] In 1796 he petitioned the Admiralty for compensation promised for short rations in New South Wales.[37]

A transcription of John Easty's journal was published in 1965.[42]

John Hunter

[edit]

John Hunter (1737–1821), an officer of the Royal Navy, sailed with the First Fleet as a second captain on board HMS Sirius.[43][44] Hunter went on to become the second governor of New South Wales and later retired having achieved the rank of vice-Admiral. Hunter was born on 29 August 1737 at Leith in Scotland.[45]

Hunter's journal is held by the State Library of New South Wales and describes his experiences during the First Fleet voyage and the early days in the colony.[46] He also produced many charts, sketches and writings, including An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, With the Discoveries that have been Made in New South Wales and the Southern Ocean since the Publication of Phillip's Voyage (London, 1793)[45] and a book of sketches of Birds & Flowers of New South Wales Drawn on the Spot in 1788, '89 & '90[47] Upon arriving at Port Jackson in January 1788, Hunter surveyed the harbour and the adjacent coast areas.[43]

In October 1788 Hunter was ordered to sail on HMS Sirius to the Cape of Good Hope for supplies. After circumnavigating the globe, in May 1789 he returned to New South Wales, where he resumed his former duties as a magistrate and surveyor of the Port Jackson area.[45] In April 1792, following the wreck of HMS Sirius at Norfolk Island in 1790, Hunter returned to England[48] where he was court-martialled for the loss of the vessel under his command, and honourably acquitted.[45] In 1795 Hunter succeeded Arthur Phillip as the governor of New South Wales[45] and served in this capacity until September 1800.[44] His term as the governor was difficult and, after being accused of lack of competence and leadership, he was recalled from the office.[45] He left for England having handed over government of the colony to Philip Gidley King.[45] In 1801 Hunter returned to England, where he succeeded in clearing his name. He regained his standing in society and continued to progress his naval career. In 1807 he was promoted to rear-admiral, and finally in July 1810 to the rank of vice-Admiral.[45] He died on 13 March 1821 in London.

Philip Gidley King

[edit]Philip Gidley King (1758–1808) was the second lieutenant on HMS Sirius serving under Arthur Phillip, the leader of the first sub-colony on Norfolk Island, and later the third governor of New South Wales.

Philip Gidley King's private journal, Remarks & Journal Kept On the Expedition to Form a Colony, was kept in two volumes and is held by the State Library of New South Wales.[49] Volume 1 of the journal covers the period between 24 October 1786 – 12 January 1789. A fair copy, annotated by another hand and entitled A Narrative of the Preparation and Equipment of the First Fleet, the Voyage to New South Wales in H.M.S. Sirius, Events in N.S.W. and Norfolk Is., and the Voyage to England in H.M.S. Supply, was also made.[50] It includes a translation of some New Zealand Maori words.[51]

The journal contains details of events important to the community including items such as the weather, the amount of fish caught, persons sick or punished and crops that were grown.[52] It was published with minor revision as an appendix to John Hunter's Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island in 1793.[53]

Jacob Nagle

[edit]Jacob Nagle (1761–1841) was an ordinary seaman on board HMS Sirius. He was an American who was born in Pennsylvania in 1761 and who died in Ohio in 1841. As a young man he served in the American War of Independence, first as a soldier and later as a sailor. He was taken prisoner by the British and this led to him joining the British Navy in 1782. He was selected for duty on HMS Sirius in 1787.[54][55] His journal was written as a memoir in 1840, after his retirement from a life at sea, and covers the 45 years of his life as a seafarer.[56] There are two known copies, one in the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan[57] and the other in the State Library of New South Wales.[58] A transcribed, published version, edited and with commentary by C. Dann, was issued in 1988.[59] The years covering 1787–1791 are those spent as part of the First Fleet expedition.

Nagle's journal provides a detailed account of the First Fleet from the perspective of the common sailor. He writes in an informal style, as a worker, rather than the official language of the more educated decision makers.[59] He was present at and gives detailed reports on many key events. He was a member of Governor Phillip's boat crew and took part in the explorations which led to the selection of Sydney as the site for settlement.[59][60][61] He describes encounters with the Aboriginal people, including the spearing of Governor Phillip[54] and the capture of Bennelong and Coleby.[61] His eye-witness accounts of events often provide a very different perspective than the more official reports and journals.[59]

Nagle was on board HMS Sirius when it was wrecked on rocks at Norfolk Island in 1790. He was a strong swimmer and was able to help retrieve supplies.[55][61] He remained on Norfolk Island until the crew were rescued in 1791, when he returned to England. Jacob Nagle's stories and reminiscences provide a colourful insight into the First Fleet experience.[59]

Arthur Phillip

[edit]Arthur Phillip (1738–1814) was born in London on 11 October 1738 to Jacob and Elizabeth Phillip, a German language teacher and former wife of a naval captain. He was educated at the Greenwich school for the sons of seaman and completed a two-year apprenticeship in the mercantile service. His naval career began during the Seven Years' War and led to an accomplished career, which included a promotion to lieutenant.[62] After a periodic retirement, Phillip returned to the British navy in 1778. In 1786, he was appointed the first Governor of New South Wales and Admiral of the First Fleet.[62] He was chosen for his organisational, leadership and farming skills.[63] He also displayed altruistic qualities, with plans to treat the Aboriginal people with decency and assist convicts with improving their lives.[64]

Although sailing on the flagship, HMS Sirius, Phillip's journal chronicles many facets of the fleet's journey. This ranges from preparations and plans, significant stages of the voyage, to the first landing at Botany Bay in 1788. The first meetings with Aboriginal people are described, along with the resettlement to Sydney Cove at Port Jackson. The journal then concentrates on the early events of the colony, such as major naval movements, inland expeditions, scurvy outbreaks and ongoing encounters with the indigenous inhabitants. Accompanying these entries are drawings of land, marine and wildlife discoveries. These include: Lord Howe Island, the Port Jackson shark and kangaroo. In addition, the journal includes an Appendix, which provide the routes taken by each ship in the fleet and a list of convicts sent to the new colony.[65]

Due to a persistent health issue, Phillip returned to England in 1792. While he never returned to New South Wales, he retained an interest in its development.[62] Phillip lived in Bath for most of his remaining life, until he died on 31 August 1814 .[63]

James Scott

[edit]James Scott (d.1796) was a Sergeant of Marines on Prince of Wales. He travelled with his wife, Jane, who gave birth to a daughter en route.[66] He returned to England in 1791 with his family, including a son, William, born in Sydney the previous year.[67] His account of the voyage and his time in the colony, entitled Remarks on a passage Botnay [i.e. Botany] bay 1787 has survived and covers the dates 13 May 1787 – 20 May 1792.[67] In his journal he records that he commanded the Quarter Guard, looked after pigs and poultry, and after arriving at Sydney searched for a lost marine in the bush. During the voyage, he records that a convict attempted to escape at Tenerife.[68] He died in Portsmouth, England in 1796.[66] The diary was published in 1963 as Remarks On a Passage to Botany Bay, 1787–1792: A First Fleet Journal.[68]

Daniel Southwell

[edit]Daniel Southwell (c. 1764–1797) joined the Royal Navy in 1780. He joined the crew of HMS Sirius as a midshipman 28 October 1787, was promoted to master's mate during the voyage to New South Wales. In New South Wales, Southwell was appointed as commander of the lookout at South Head.[69]

Southwell kept a journal from the time the voyage started until May 1789. He also corresponded via letters with his mother and uncle. His journal and letters offer depictions of early colonial life and the first substantive interactions between Europeans and Australian Aborigines. The letters also reveal clashes between the colonial Governor Phillip, and his senior military officer Major Robert Ross, and Southwell's deep pessimism regarding the colony's economic and governmental prospects.[69]

Watkin Tench

[edit]Watkin Tench (1758?–1833) was a captain-lieutenant of the Marine Corps and author. He was born between May 1758 and May 1759 at Chester, England, the son of Fisher Tench and his wife Margaret (Margaritta).[70] Towards the end of 1786 he volunteered for a three-year tour of service with the convict settlement about to be formed at Botany Bay. He sailed in the transport Charlotte on 13 May 1787 as one of the two captain-lieutenants of the marine detachment under Major Robert Ross, and arrived in Botany Bay on 20 January 1788.

Watkin Tench kept a journal on board Charlotte and continued to document life in the early colony.[70] Tench has been described as having a flair for writing,[71] and he provides anecdotes about all aspects of life in the colony, including convict life, daily activities and reflections on the Aboriginal tribes.[72] He records his impressions of Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town, where the fleet stopped to restock supplies, and also describes in detail the behaviour of the convicts.[73] Tench, described in some sources as being particularly humane in his treatment of convicts,[71] records his "great pleasure" when on 20 May, in light of the good behaviour of the convicts, many were released temporarily from their bonds.[73] Phillip's decision to lead a small advance group of ships to Botany Bay, to begin construction of the settlement, is described by Tench as a decision made due to unfavourable winds after leaving the Cape of Good Hope,[73] although this had been allowed for in Phillip's instructions.[63]

Tench arranged for John Shortland, sailing back to England in 1788 on Alexander, to take Tench's manuscript with him so that it could be published. The journal was first published in London in 1789 by Debrett's as A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay: With an Account of New South Wales, Its Productions, Inhabitants, &c.[73] It was one of the earliest published accounts of the First Fleet voyage and the early settlement of Australia. The book ran to several editions and was later published in several languages, including French, German, Dutch and Swedish.[70]

John White

[edit]

John White (1756?–1832) served as the chief surgeon on the fleet and to the settlement at Port Jackson.[74] He had served on other ships in the Royal Navy, including as surgeon's mate on HMS Wasp[75] and surgeon on HMS Irresistible[75] before being recommended for the expedition to Botany Bay by Sir Andrew Snape Hamond.[75][76] His assistant surgeons on the First Fleet were Dennis Considen, Thomas Arndell and William Balmain.[76]

White's diary records details of how he ordered medical supplies, supervised the embarkation of the convicts and made visits during the voyage to the ships to check on the health of the convicts and crew. White was also a keen amateur naturalist and on arrival in Port Jackson he was particularly interested in the birds of the colony.[75] White sent the journal of his trip to Thomas Wilson, a friend in London, who published it in 1790.[77] The published edition included engravings drawn from the specimens White collected and appeared under the title Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales: With Sixty-Five Plates of Non-Descript Animals, Birds, Lizards, Serpents, Curious Cones of Trees and Other Natural Productions.[75][78]

White remained in the colony until December 1794, supervising the medical care of the convicts and crew arriving on the Second Fleet in 1790 and the Third Fleet in 1791.[75] The journal of Watkin Tench, another member of the colony, describes White adopting a young Aboriginal boy, named Nanbaree, who was orphaned by the smallpox epidemic at Port Jackson in 1789.[79]

Letters

[edit]David Blackburn

[edit]David Blackburn (1753–1795), from Newbury, Berkshire, England, was the master of HMS Supply.[80] He wrote a series of letters to family members and friends, many of which are still extant.[81] These letters describe the events of the voyage and the early days of settlement, including Blackburn's participation in the expedition to Norfolk Island to establish a settlement there in February 1788.[81] Blackburn's letters record the change in his feelings towards the voyage. Initially reluctant to join the fleet,[82] shortly before the fleet left he told his letter in a letter that "my dislike to the voyage begins gradually to wear off".[80] Supply was part of the advance party of ships which arrived in Botany Bay on 18 January.[83] Blackburn also joined Phillip's expedition in search of a better location for the settlement,[81] and describes Sydney Harbour as "excellent and extensive".[83] He died of illness on 10 January 1795.[81]

James Campbell

[edit]James Campbell served as Captain of Marines on Lady Penrhyn. His dates of birth and death are not known.[84] Campbell strongly criticised Phillip's actions, both during the voyage and after arrival in Australia. In a letter to Francis Reynolds-Moreton, 3rd Baron Ducie, dated 12 July 1788, Campbell describes the final stages of the voyage. He criticises Phillip's decision to take a small party of ships ahead as a "Don Quixote scheme" and notes that the two parties arrived within a few days of each other.[84]

John Campbell

[edit]John Campbell travelled on Lady Penrhyn as part of the fleet.[85] He wrote a letter to his parents while travelling back to England, in which he describes the voyage and early days of the colony.[85] Although he travelled on Lady Penrhyn, he is not included in Arthur Bowes Smyth's list of crew members on board.[8][85] He later returned to England on the same ship. He remained on board Lady Penrhyn while Phillip took a party ashore at Sydney Cove to plant the British flag,[85] and describes his view of events in his letter:

the Governor went on Shore to take Possession of the Land with a Company of Granadeers & Some Convicts at three A Clock in the Afternoon he sent on board of the Supply Brigantine for the Union Jack then orders was Gave fore the Soldiers to March down to the West Sid of the Cove they Cut one of the Trees Down & fixt as flag Staf & Hoistd the Jack and Fired four Volleys of Small Arms which was Answered with three Cheers from the Brig. (sic)

— John Campbell, Transcribed letter

Newton Fowell

[edit]Newton Fowell (1768–1790) was a midshipman on HMS Sirius during the voyage to Australia.[86] He was born in Devonshire, England. He joined the fleet after being recommended to Captain Phillip by Evan Nepean.[87] He wrote a series of letters to his father both while on board and after arriving in Australia describing his experiences on the voyage and during the early days of settlement.[86]

He sent his first letter on the voyage on 20 May 1787, taking advantage of the return of Hyena to England after it had escorted the fleet out of British waters.[88][89] In this letter he describes the fair winds enjoyed by the fleet as it left England, states that they hope to reach Tenerife in a fortnight, and notes that most of the convicts are "in good health".[89] He wrote again from Santa Cruz, describing the events of the previous weeks including the discovery of a planned mutiny, and his admiration of Captain Phillip.[88][90] In his letter of 12 July 1788, Fowell describes the final two months of the voyage and the first six months of the European settlement at Sydney Cove.[88][91] He also states that Phillip named the settlement Albion on 4 June 1788.[87][91]

Fowell was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and, after HMS Sirius was shipwrecked in March 1790, he was sent to Batavia in 1790 on HMS Supply to obtain supplies for the colony. He died at sea on 25 August 1790 after contracting a fever.[86] His original manuscript letters have survived, and have also been published.[88]

Richard Johnson

[edit]Richard Johnson (1753–1827) was a Church of England clergyman who performed the first Christian church service in Australia.[92] He joined the fleet as a result of his interest in mission and prison reform.[93] He travelled on Golden Grove.[92] He wrote a series of letters to friends and family from the colony. In his letter of 10 February 1788, he gives an account of the voyage and arrival in Australia.[94] His faith is clear in his letters and does not waver.[92] He describes a storm which struck the fleet on 1 January 1788, which lasted 24 hours.[94] Johnson remained in the colony for 12 years, returning to England in 1800 for health reasons.[92]

Henry Waterhouse

[edit]Henry Waterhouse (1770–1812) was a midshipman on HMS Sirius.[95] He wrote a letter to his father on 11 July 1788. He describes the fleet's encounters with wildlife during the voyage including birds, seals and whales.[96] He was part of the expedition to Norfolk Island to found a settlement there.[95]

George Worgan

[edit]George Bouchier Worgan (1757–1838) was a naval surgeon on HMS Sirius.[97] Worgan's journal[98] takes the form of a letter to his brother Richard dated 12 June 1788.

The journal covers the early months of European settlement in New South Wales (20 January to 11 July 1788).[99][100] The first section, written on HMS Sirius, describes the fleet's arrival and their first encounter with Aboriginal Australians. In the journal he talks about a "rough journal" and a more complete form.[100] He describes expeditions, the coastline, and flora and fauna. He also describes the building activities involved in setting up the settlement in New South Wales, as well as native wood varieties and stone.[98] Worgan describes in detail the activities and behaviour of both the European settlers and the Indigenous people of the area, and the interactions between these groups.[100]

While in the colony Worgan went on expeditions to the Hawkesbury River and Broken Bay areas north of Sydney and accompanied Watkin Tench to the Nepean in 1790. He also spent a year on Norfolk Island. He returned to England in 1791. Worgan died at Liskeard on 4 March 1838.[97]

Convict narrative

[edit]James Martin

[edit]James Martin (also spelled 'Martyn') was born c. 1760 in Ballymena, County Antrim. He had a wife and son in Exeter and had worked in England for seven years when, at Exeter Assizes on 20 March 1786, he was sentenced to transportation for seven years for stealing eleven screw bolts and other goods from Powderham Castle. He was held on the Dunkirk hulk for almost a year, and was embarked upon Charlotte on 11 March 1787, by which he was transported to New South Wales. Martin was apparently a useful tradesman in Sydney, and his narrative – known as the Memorandoms of James Martin – is the only extant first-hand account written by a First Fleet convict.[101]

On the night of 28 March 1791, Martin, along with William Bryant, his wife Mary (née Broad) and their two children Charlotte and Emanuel, William Allen, Samuel Bird, Samuel Broom, James Cox, Nathaniel Lillie, and William Morton, stole the colony's six-oared open boat. In this vessel, the party navigated the eastern and northern coasts of Australia, survived several ferocious storms, encountered Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, and reached Kupang in Dutch West Timor on 5 June 1791, the entire party having survived. There, they successfully – for a while, at least – passed themselves off as the survivors of a shipwreck.

Once their true identities were discovered, the escapees were imprisoned and returned to England. During this journey, William Bryant, Emanuel Bryant, James Cox, Samuel Bird, and William Morton died. The survivors arrived back in England on 18 June 1792. On 7 July they were brought to the bar at the Old Bailey, and ordered to remain in Newgate gaol until their original sentences of transportation had expired. Mary Bryant received an unconditional pardon on 2 May 1793 when her sentence expired, while Martin, Allen, Broom, and Lillie were released by proclamation on 2 November 1793. From there, they largely disappear from the historical record.

The Memorandoms is part of the Bentham Papers archive in University College London Library's Special Collections. It was first discovered by the Bentham scholar Charles Blount, who in 1937 published a short edition, limited to 150 copies.[101] In 2017, an open-access book, containing reproductions of the original manuscript and a detailed introduction, edited by Tim Causer, was published by UCL Press.

See also

[edit]- Borrowdale

- Fishburn

- Golden Grove

- History of Australia (1788–1850)

- Stories of convicts on the First Fleet

References

[edit]- ^ "Journals from the First Fleet". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "First Fleet scribes". Webster World. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ "First Fleet Journals – Citation #33". Australian Memory of the World Program. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Macy, Jennifer (14 October 2009). "First Fleet journals listed on UNESCO register". ABC News Blog. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Arthur Bowes-Smyth, illustrated journal, 1787–1789. Titled 'A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China in the Lady Penrhyn, Merchantman William Cropton Sever, Commander by Arthur Bowes-Smyth, Surgeon – 1787-1788-1789'; being a fair copy compiled ca 1790". catalogue. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Arthur Bowes Smyth (1750–1790)". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Arthur Bowes Smyth (1750–1790)". Smyth, Arthur Bowes (1750–1790). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "The journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth : surgeon, Lady Penrhyn, 1787–1789". State Library Catalogue. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Bateson, Charles; Library of Australian History (1983), The convict ships, 1787–1868 (Australian ed.), Library of Australian History, p. 38, ISBN 978-0-908120-51-2

- ^ "The convict ships, 1787–1868". State Library Catalogue. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ Historical records of New South Wales v.1, pt. 2. Phillip, 1783–1792. Charles Potter, Government Printer. 1892–1901. p. 120.

- ^ Smyth, Arthur Bowes, 1750–1790 (1964), Original daily journal kept on the transport "Lady Penrhyn" : containing one of the most detailed accounts of the first hundred days of settlement of Australia in 1788 / by Arthur Bowes Smyth, F. Edwards

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Gillen, Mollie; Browning, Yvonne, 1938–; Flynn, Michael C; Library of Australian History; Gillen, Mollie (1989), The founders of Australia : a biographical dictionary of the First Fleet, Library of Australian History, p. 42, ISBN 978-0-908120-69-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Historical records of New South Wales v.1, pt. 2. Phillip, 1783–1792. Charles Potter, Government Printer. 1892–1901. pp. 126, 136.

- ^ Smyth, Arthur Bowes; Fidlon, Paul G; Ryan, R. J, (joint ed.) (1979), The journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth : surgeon, Lady Penrhyn, 1787–1789, Australian Documents Library, ISBN 978-0-908219-00-1

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, Nat (16 April 2014). "The Bowes Smyth First Fleet journal". Treasures Blog. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Hine, Janet D. "William Bradley (1758–1833)". Bradley, William (1757–1833). National centre for Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bradley, William (1969). A voyage to New South Wales : the journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792. Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales in association with Ure Smith. pp. xvi, 495. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Bradley, William. "Transcription of William Bradley – Journal. Titled 'A Voyage to New South Wales', December 1786 – May 1792; compiled". Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Bradley, William. "William Bradley – Journal. Titled 'A Voyage to New South Wales', December 1786 – May 1792; compiled 1802+". Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ Keith Vincent Smith (2008). "Colebee". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "William Bradley – Drawings from his journal 'A Voyage to New South Wales', 1802+". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "William Bradley – Charts from his journal 'A Voyage to New South Wales', 1802". State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "William Bradley (1757?–1833)". State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "View Shipwreck – Sirius HMS". Australian National Shipwreck Database. Department of the Environment. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Collection 03: Ralph Clark – Journal kept on the Friendship during a voyage to Botany Bay and Norfolk Island; and on the Gorgon returning to England, 9 March 1787 – 31 December 1787, 1 January 1788 – 10 March 1788, 15 February 1790 – 2 January 1791, 25 January 1791 – 17 June 1792. Fair copy, probably compiled later". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b Hine, Janet. "Ralph Clark (1762–1794)". Clark, Ralph (1762–1794). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "The Journal and Letters of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787–1792" (PDF). Australian Documents Library in Association with The Library of Australian History Pty Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2005. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "First Fleet Fellowship Victoria Inc Descendants of those who arrived with the First Fleet in 1788 with Captain Arthur Phillip". First Fleet Fellowship Victoria Inc 2011. 15 October 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, Ralph. "Journal". State Library of New South Wales Catalogue. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Collins, David (1756–1810)". David Collins. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "David Collins". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ "David Collins". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b "An Account of the English colony in New South Wales". David Collins. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b Collins, David (1798). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. London: T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies. p. xv.

- ^ "An account of the English Colony in New South Wales". volume 2. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Richardson, G. D. "John Easty (?–?)". Easty, John (?–?). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "John Easty". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "Scarborough". Webster's Encyclopedia of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "John Easty". Webster's Encyclopedia of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Easty, John. "Collection 04: John Easty – Journal, 1786–1793". Manuscripts, oral history & pictures catalogue. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ Easty, John (1965). Memorandum of the transactions of a voyage from England to Botany Bay, 1787–1793 : a First Fleet journal. Sydney: Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales in association with Angus and Robertson.

- ^ a b Hunter, John. "Collection 05: John Hunter – journal kept on board of the Sirus during a voyage to New South Wales, May 1787 – March 1791". Manuscripts, oral history & pictures. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b "John Hunter (1737–1821)". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Auchmuty, J. J. "John Hunter (1737–1821)". Hunter, John (1737–1821). National centre for Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Collection 05: John Hunter – journal kept on board HMS Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales, May 1787 – March 1791". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "Teacher resources: Captain John Hunter Sketchbook". Treasure explorer. National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ Barnes, Robert (2009). An unlikely leader: the life and times of Captain John Hunter. Sydney University Press. pp. xii, 329. ISBN 9781920899196.

- ^ "Philip Gidley King Journal". State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Record Detail notes". Manuscripts Oral History and Pictures. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Philip Gidley King". Discovery Collections. State Library of NSW. 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ "First Fleet Fellowship stories". 19 October 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Philip Gidley King (1758–1808)". King, Philip Gidley (1758–1808). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Easton, Arthur. "Jacob Nagle (1761–1841)". Nagle, Jacob (1761–1841). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Frost, Alan (2004). "Nagle, Jacob (1761–1841)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/64833. Retrieved 21 November 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Millinger, James F. (1990). "Review of the book The Nagle Journal: a Diary of the Life of Jacob Nagle, Sailor, from the Year 1775 to 1841 by John C. Dann; Jacob Nagle". Journal of the Early Republic. 10 (2 (Summer 1990)). University of Pennsylvania Press: 260–261. doi:10.2307/3123562. JSTOR 3123562.

- ^ Hixon, Meg. "Finding aid for Jacob Nagle Journal, 1840". William L. Clements Library Manuscripts Division Finding Aids. Manuscripts Division William L. Clements Library University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Jacob Nagle (1761–1841)". Discover Collections : Journals of the First Fleet. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Nagle, Jacob (1988). Dann, John C. (ed.). The Nagle journal : a diary of the life of Jacob Nagle, sailor, from the year 1775 to 1841. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 1555842232.

- ^ "Broken Bay First Encounters: Jacob Nagle's Account". BluePlanet. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "Jacob Nagle's Journal". 100 Exhibition. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 22 June 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Fletcher, B. H. Arthur Phillip (1738–1814). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Parker, Derek (2009). Arthur Phillip: Australia's First Governor. Warriewood: Woodslane Press. ISBN 9781921203992.

- ^ "Captain Arthur Phillip". Sydney Living Museums. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ Phillip, Arthur (1968). The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay: Australiana Facsimile Editions No. 185. Adelaide: Libraries Board of South Australia.

- ^ a b "Scott, James (?–1796)". James Scott. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Scott's journal". catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ^ a b Scott, James (1963), Remarks on a passage to Botany Bay, 1787–1792 : a First Fleet Journal, The trustees of The Public Library of New South Wales in association with Angus and Robertson, archived from the original on 19 December 2013, retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ a b Horton, Allan (1967). "Daniel Southwell (1764–1797)". Southwell, Daniel (1764–1797). Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Fitzhardinge, L. F. "Tench, Watkin (1758–1833)". Watkin Tench (1758–1833). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Tench, Watkin; Flannery, Tim F. (Tim Fridtjof), 1956–; Tench, Watkin, 1758 or 9-1833. Complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson; Tench, Watkin, 1758 or 9-1833. Narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay (5 January 2009), 1788 : comprising A narrative of the exhibition to Botany Bay and A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, Text Publishing (published 2009), ISBN 978-1-921520-04-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Watkin Tench". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Tench, Watkin (1789), A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay, with an account of New South Wales, its productions, inhabitants, &c, to which is subjoined, a list of the civil and military establishments at Port Jackson, printed for Messrs. H. Chamberlaine ..., archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ White, John (1790). Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Rienits, Rex. "John White (1756–1832)". White, John (1756–1832). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Frost, Alan; Frost, Alan, 1943– (2011), The First Fleet: the real story, Black Inc, ISBN 978-1-86395-529-4

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Published Accounts". Discover Collections. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ "Journal of a voyage to New South Wales : with sixty-five plates of non-descript animals, birds, lizards, serpents, curious cones of trees and other natural productions". Catalogue record. State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Egan, Jack (1999), Buried alive : Sydney 1788–1792 : eyewitness accounts of the making of a nation, Allen & Unwin, ISBN 978-1-86508-138-0

- ^ a b Hirst, Warwick (2005). "Blackburn, David (1753–1795)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. Supplementary Volume. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d "David Blackburn (1753–1795)". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Elizabeth Blackburn – Letter received from her son David Blackburn, 1787". Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Margaret Blackburn – Letters (14) received from her brother David Blackburn, 1787–1791". Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b "James Campbell (d. 1795?)". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d "John Campbell". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "Collection 17: Fowell Family Collection – Letters received from Newton Fowell, 1786–1790. Includes letters written by various other people". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Newton Fowell (1768–1790)". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Fowell, Newton; Irvine, Nance; Sirius (Ship) (1988), The Sirius letters : the complete letters of Newton Fowell, midshipman & lieutenant aboard the Sirius flagship of the first fleet on its voyage to New South Wales, Fairfax Library, ISBN 978-1-86290-000-4

- ^ a b "Item 10: Letter received by John Fowell from Newton Fowell, 20 May 1787". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Letter received by John Fowell from Newton Fowell, 4 June 1787". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Item 18: Letter received by John Fowell from Newton Fowell, 12 July 1788". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Cable, K.J. "Richard Johnson (1753–1827)". Johnson, Richard (1753–1827). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Reverend Richard Johnson (1753–1827)". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Collection 18: Letters from the Rev. Richard Johnson to Henry Fricker, 30 May 1787–10 Aug. 1797, with associated items, ca. 1888". Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b Parsons, Vivienne. "Henry Waterhouse (1770–1812)". Waterhouse, Henry (1770–1812). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Henry Waterhouse (c.1770–1812)". Discover Collections. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b Cobley, John. "George Bouchier Worgan (1757–1838)". Worgan, George Bouchier (1757–1838). Australian National University. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "George Bouchier Worgan (1757–1838)". website. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "Worgan, George Bouchier (1757–1838)". website. Encyclopedia of Australian Science. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "George Bouchier Worgan – letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12 – 18 June 1788". Catalogue. State Library of NSW. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b Martin, James (2017) [c1793]. Causer, Tim (ed.). Memorandoms. UCL Press. ISBN 9781911576839. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Egan, Jack (1999). Buried alive : Sydney 1788–1792 : eyewitness accounts of the making of a nation. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781865081380.

- Frost, Alan (2012). The First Fleet: the real story. Black Inc. ISBN 9781863955614.

- Parker, Derek (2009). Arthur Phillip. Woodslane Press. ISBN 9781921203992.

- Pembroke, Michael (2013). Arthur Phillip: Sailor, Mercenary, Governor, Spy. Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 9781742705088.

- Tink, Andrew (2011). Lord Sydney : the life and times of Tommy Townshend. Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 9781921875434.

External links

[edit]- A Journal of a Voyage from Portsmouth to New South Wales and China – in the Lady Penrhyn, Merchantman – William Cropton Sever, Commander by Arthur Bowes, Smyth, Surgeon – 1787-1788-1789

- A Voyage to New South Wales by William Bradley

- Journal kept on the Friendship during a voyage to Botany Bay and Norfolk Island; and on the Gorgon returning to England, 9 March 1787 – 31 December 1787, 1 January 1788 – 10 March 1788, 15 February 1790 – 2 January 1791, 25 January 1791 – 17 June 1792 by Ralph Clark

- An Account of the English Colony of NSW Vol 1 by David Collins, at Project Gutenberg

- Pt Jno Easty A Memorandum of the Transa() of a Voiage [sic] from England to Botany Bay in The Scarborough transport Captn Marshall Commander kept by me your humble Servan() John Easty marine wich [sic] began 1787 by John Easty

- Journal kept on board the Sirius during a voyage to New South Wales, May 1787 – March 1791 by John Hunter

- Remarks & Journal kept on the Expedition to form a Colony ... by Philip Gidley King

- Memorandoms by James Martin: An Astonishing Escape from Early New South Wales, ed. T. Causer, London, UCL Press, 2017. Also [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UToptGN4990 Escape from Australia: a convict's tale, a UCL video production discussing the Memorandoms.

- Partial transcript of Jacob Nagle his Book A.D. One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Nine May 19th. Canton. Stark County Ohio by Jacob Nagle

- The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay by Arthur Phillip, at Project Gutenberg

- Remarks on a passage Botnay (sic) bay 1787', 13 May 1787 – 20 May 1792 by James Scott

- A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay by Watkin Tench

- Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales by John White