Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison, c. 1810 | |

| |

| Status | Closed |

|---|---|

| Opened | 1188 |

| Closed | 1902 |

| City | London |

| Country | England |

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey, just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, the prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

In the late 18th century, executions by hanging were moved here from the Tyburn gallows. These took place on the public street in front of the prison, drawing crowds until 1868, when they were moved into the prison.

For much of its history, a succession of criminal courtrooms were attached to the prison, commonly referred to as the "Old Bailey". The present Old Bailey (officially, Central Criminal Court) now occupies much of the site of the prison.

History

[edit]

In the 12th century, Henry II instituted legal reforms that gave the Crown more control over the administration of justice. As part of his Assize of Clarendon of 1166, he required the construction of prisons, where the accused would stay while royal judges debated their innocence or guilt and subsequent punishment. In 1188, Newgate was the first institution established to meet that purpose.[1] Also around this time, the Sheriffs of London were given jurisdiction in Middlesex, as well as in the City of London.[2]

A few decades later in 1236, in an effort to significantly enlarge the prison, the king converted one of the Newgate turrets, which still functioned as a main gate into the city, into an extension of the prison. The addition included new dungeons and adjacent buildings, which would remain unaltered for roughly two centuries.[3]

By the 15th century, however, Newgate was in need of repair. Following pressure from reformers who learned that the women's quarters were too small and did not contain their own latrines – obliging women to walk through the men's quarters to reach one – officials added a separate tower and chamber for female prisoners in 1406.[4] Some Londoners bequeathed their estates to repair the prison. The building was collapsing and decaying, and many prisoners were dying from the close quarters, overcrowding, rampant disease, and bad sanitary conditions. Indeed, one year, 22 prisoners died from "gaol fever". The situation in Newgate was so dire that in 1419, city officials temporarily shut down the prison.[3]

The executors of the will of Lord Mayor Dick Whittington were granted a licence to renovate the prison in 1422. The gate and gaol were pulled down and rebuilt. There was a new central hall for meals, a new chapel, and the creation of additional chambers and basement cells with no light or ventilation.[3] There were three main wards: the Master's side for those could afford to pay for their own food and accommodations, the Common side for those who were too poor, and a Press Yard for special prisoners.[5] The king often used Newgate as a holding place for heretics, traitors, and rebellious subjects brought to London for trial.[3] The prison housed both male and female felons and debtors. Prisoners were separated into wards by sex. By the mid-15th century, Newgate could accommodate roughly 300 prisoners. Though the prisoners lived in separate quarters, they mixed freely with each other and visitors to the prison.[6]

The prison was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, and was rebuilt in 1672 by Sir Christopher Wren.[7] In 1752, a windmill was built on top of the prison by Stephen Hales in an effort to provide ventilation.[8]

In 1769, construction was begun by the King's Master Mason, John Deval,[9] to enlarge the prison and add a new 'Old Bailey' sessions house. Parliament granted £50,000 (~£9.3 million in 2020 terms) towards the cost, and the City of London provided land measuring 1,600 feet (500 m) by 50 feet (15 m). The work followed the designs of George Dance the Younger. The new prison was constructed to an architecture terrible design intended to discourage law-breaking. The building was laid out around a central courtyard, and was divided into two sections: a "Common" area for poor prisoners and a "State area" for those able to afford more comfortable accommodation.[10]

Construction of the second Newgate Prison was almost finished when it was stormed by a mob during the Gordon riots in June 1780. The building was gutted by fire, and the walls were badly damaged; the cost of repairs was estimated at £30,000 (~£5.6 million in 2020 terms). Dance's new prison was finally completed in 1782.[11]

During the early 19th century, the prison attracted the attention of the social reformer Elizabeth Fry. She was particularly concerned at the conditions in which female prisoners (and their children) were held. After she presented evidence to the House of Commons improvements were made.[12]

The prison closed in 1902, and was demolished in 1903.[13]

Prison life

[edit]

All manner of criminals stayed at Newgate. Some committed acts of petty crime and theft, breaking and entering homes or committing highway robberies, while others performed serious crimes such as rapes and murders.[14] The number of prisoners in Newgate for specific types of crime often grew and fell, reflecting public anxieties of the time. For example, towards the tail end of Edward I's reign, there was a rise in street robberies. As such, the punishment for drawing out a dagger was 15 days in Newgate; injuring someone meant 40 days in the prison.[1]

Upon their arrival in Newgate, prisoners were chained and led to the appropriate dungeon for their crime. Those who had been sentenced to death stayed in a cellar beneath the keeper's house, essentially an open sewer lined with chains and shackles to encourage submission. Otherwise, common debtors were sent to the "stone hall" whereas common felons were taken to the "stone hold". The dungeons were dirty and unlit, so depraved that physicians would not enter.[5]

The conditions did not improve with time. Prisoners who could afford to purchase alcohol from the prisoner-run drinking cellar by the main entrance to Newgate remained perpetually drunk.[5] There were lice everywhere, and jailers left the prisoners chained to the wall to languish and starve. From 1315 to 1316, 62 deaths in Newgate were under investigation by the coroner, and prisoners were always desperate to leave the prison.[5]

The cruel treatment from guards did nothing to help the unfortunate prisoners. According to medieval statute, the prison was to be managed by two annually elected sheriffs, who in turn would sublet the administration of the prison to private "gaolers", or "keepers", for a price. These keepers in turn were permitted to exact payment directly from the inmates, making the position one of the most profitable in London. Inevitably, often the system offered incentives for the keepers to exhibit cruelty to the prisoners, charging them for everything from entering the gaol to having their chains both put on and taken off. They often began inflicting punishment on prisoners before their sentences even began. Guards, whose incomes partially depended on extorting their wards, charged the prisoners for food, bedding, and to be released from their shackles. To earn additional money, guards blackmailed and tortured prisoners.[1] Among the most notorious Keepers in the Middle Ages were the 14th-century gaolers Edmund Lorimer, who was infamous for charging inmates four times the legal limit for the removal of irons, and Hugh De Croydon, who was eventually convicted of blackmailing prisoners in his care.[15]

Indeed, the list of things that prison guards were not allowed to do serve as a better indication of the conditions in Newgate than the list of things that they were allowed to do. Gaolers were not allowed to take alms intended for prisoners. They could not monopolize the sale of food, charge excessive fees for beds, or demand fees for bringing prisoners to the Old Bailey. In 1393, new regulation was added to prevent gaolers from charging for lamps or beds.[4]

Not a half century later, in 1431, city administrators met to discuss other potential areas of reform. Proposed regulations included separating freemen and freewomen into the north and south chambers, respectively, and keeping the rest of the prisoners in underground holding cells. Good prisoners who had not been accused of serious crimes would be allowed to use the chapel and recreation rooms at no additional fees. Meanwhile, debtors whose burden did not meet a minimum threshold would not be required to wear shackles. Prison officials were barred from selling food, charcoal, and candles. The prison was supposed to have yearly inspections, but whether they actually occurred is unknown. Other reforms attempted to reduce the waiting time between jail deliveries to the Old Bailey, with the aim of reducing suffering, but these efforts had little effect.[3]

Over the centuries, Newgate was used for a number of purposes including imprisoning people awaiting execution, although it was not always secure: burglar Jack Sheppard twice escaped from the prison before he went to the gallows at Tyburn in 1724. Prison chaplain Paul Lorrain achieved some fame in the early 18th century for his sometimes dubious publication of Confessions of the condemned.[16]

Executions

[edit]

In 1783, the site of London's gallows was moved from Tyburn to Newgate.[17] Public executions outside the prison – by this time, London's main prison – continued to draw large crowds. It was also possible to visit the prison by obtaining a permit from the Lord Mayor of the City of London or a sheriff. The condemned were kept in narrow, sombre cells separated from Newgate Street by a thick wall and received only a dim light from the inner courtyard. The gallows were constructed outside a door in Newgate Street for public viewing. Dense crowds of thousands of spectators could pack the streets to see these events, and in 1807 dozens died at a public execution when part of the crowd of 40,000 spectators collapsed into a crowd crush.[18] In November 1835 James Pratt and John Smith were the last two men to be executed for sodomy.[19]

Michael Barrett was the last man to be hanged in public outside Newgate Prison (and the last person to be publicly executed in Great Britain) on 26 May 1868.[20] From 1868, public executions were discontinued and executions were carried out on gallows inside Newgate, initially using the same mobile gallows in the Chapel Yard, but later in a shed built near the same spot. Dead Man's Walk was a long stone-flagged passageway, partly open to the sky and roofed with iron mesh (thus also known as Birdcage Walk).[21] The bodies of the executed criminals were then buried beneath its flagstones.[22] Until the 20th century, future British executioners were trained at Newgate. One of the last was John Ellis, who began training in 1901.[23] In total – publicly or otherwise – 1,169 people were executed at the prison.[24] Death masks of several of them were transferred to the Black Museum at New Scotland Yard on the prison's closure.[25]

Notable prisoners

[edit]Other famous prisoners at Newgate include:

- Thomas Bambridge, warden of Fleet Prison in the 1720s – imprisoned for extortion and murder[26][27]

- George Barrington, pickpocket – held at least twice in Newgate between 1783 and 1790, before transportation to Australia[28][29]

- John Bellingham, assassin of the Prime Minister Spencer Perceval 1812 – hanged in 1812[30]

- John Bernardi, soldier and Jacobite conspirator – imprisoned without trial in Newgate for forty years[31]

- Robert Blackbourn, Jacobite conspirator – imprisoned without trial in Newgate for fifty years[32]

- John Bradford, religious reformer – burned at the stake at Newgate in 1555[33]

- Giacomo Casanova, Venetian libertine – imprisoned for alleged bigamy[34]

- Ellis Casper, who helped to perpetrate the 1839 Gold Dust Robbery – held in Newgate before being transported to Van Diemen's Land in 1841[35]

- Elizabeth Cellier, also known as the "Popish Midwife", midwife – incarcerated in 1679–1680 during a high treason trial for the alleged "Meal-Tub Plot"[36]

- William Chaloner, currency counterfeiter and con artist – imprisoned multiple times at Newgate between 1696 and his hanging 1699 for high treason[37]

- Marcy Clay, thief and highwayrobber who dressed as a man, died by suicide before she could be hanged in April 1665[38]

- William Cobbett, Parliamentary reformer and agrarian – imprisoned 1810–1812 for treasonous libel[39]

- Thomas Neill Cream, doctor and blackmailer – tried, convicted, and hanged in 1892 for poisoning several of his patients as the "Lambeth Poisoner"[40]

- Hannah Dagoe, Irish basket-woman who stabbed a man while a prisoner at Newgate[41]

- Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders (whose protagonist is born and imprisoned in Newgate Prison)[42] – held at Newgate in 1703 for seditious libel[43]

- Claude Du Vall, highwayman – held in Newgate from December 1669 until his execution in January 1670[44]

- Amelia Dyer (1837–1896), known as the "Reading baby farmer" – serial killer, hanged 10 June 1896[45]

- Daniel Eaton, author and activist – imprisoned in 1812–1813 for atheism and blasphemous libel; the subject of the defence offered by Percy Bysshe Shelley in his essay, A Letter to Lord Ellenborough[46]

- John Frith, Protestant priest and martyr – held at Newgate in 1533 before burning at the stake[47]

- Mary Frith, alias "Moll Cutpurse", pickpocket and fence in the 1600s – in Newgate multiple times for multiple offenses[48]

- Lord George Gordon, UK politician after whom the Gordon Riots are named – died of typhoid in 1793 in Newgate[49]

- Jack Hall – a petty thief executed 1707 remembered only on account of his Gallows Confessional becoming a memorable folk song made popular with the adaptation Sam Hall by English comic minstrel, W. G. Ross.[50]

- Ben Jonson, playwright and poet – imprisoned for killing fellow actor Gabriel Spenser in a 1598 duel; freed by pleading benefit of clergy[51]

- Jørgen Jørgensen (1780–1841) – a Danish adventurer, who was on board one of the ships that established the first settlement in Tasmania in 1801; governor of Iceland for two months in 1809; a British spy – held in Newgate for theft before transport to Tasmania in 1825[52]

- William Kidd, known as "Captain Kidd", pirate and privateer – hanged at Execution Dock, Wapping in 1701[53]

- John Law, economist – sentenced to death at Newgate for murder by duel in 1694[54]

- Thomas Kingsmill (c1715–1749), leader of the notorious Hawkhurst Gang of smugglers[55]

- Thomas Lloyd, stenographer of the U.S. Congress – convicted of seditious libel while imprisoned for debt, and transferred to Newgate Prison for a three-year prison term (1794–1796)[56]

- James MacLaine, known as the "Gentleman Highwayman" – held at Newgate during his 1750 trial for robbery[57]

- Sir Thomas Malory – highwayman, probable author of Le Morte d'Arthur – at Newgate 1468–1470 after conviction for conspiracy to overthrow the king[58]

- Catherine Murphy, counterfeiter – the last woman to be officially executed by burning in Great Britain, in 1789[59]

- Titus Oates, anti-Catholic conspirator – imprisoned at Newgate (1687–1689) for perjury during the Popish Plot[60]

- William Penn, religious scholar, and later the Quaker who founded the colony of Pennsylvania – held in Newgate during his 1670 trial for preaching before a gathering in the street[34]

- Miles Prance, silversmith, alleged witness to the murder of Edmund Berry Godfrey – imprisoned during 1679 trial in the Popish Plot[61]

- Cephas Quested, smuggler and leader of The Aldington Gang. Arrested during the Battle of Brookland 11 February 1821 and hung on 4 July 1821[62]

- John Rogers, Bible translator and religious reformer – at Newgate after conviction of heresy in 1554, and burnt at the stake in 1555[63]

- Jack Sheppard, thief and jailbreaker – in the early 1700s, escaped from Newgate several times during imprisonment for theft[64]

- Ikey Solomon, successful and infamous fence of the late 18th and early 19th centuries – lodged at Newgate during 1827 trial for theft and receiving[65]

- Robert Southwell, Jesuit priest and poet – held at Newgate for treason before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn in 1595[66]

- Owen Suffolk, con-man and later Australian bushranger – served time for forgery in 1846 before transport[67]

- Jane Voss (alias Jane Roberts), highwaywoman and thief – executed in 1684[68]

- Mary Wade, beggar – sentenced to death at Newgate for theft but then transported, becoming the youngest female convict transported to Australia[69]

- Edward Gibbon Wakefield, British politician, the driving force behind much of the early colonization of South Australia, and later New Zealand – served three years in Newgate for 1826 abduction[70]

- Joseph Wall, colonial administrator – hanged 1802 for having a British soldier flogged to death[71]

- John Walter Sr., publisher, founder of The Times – imprisoned for a year (1789–1790) for libel on the Duke of York[72]

- Oscar Wilde, briefly held at Newgate in 1895 before transfer to Pentonville.[73]

- Catherine Wilson, nurse and suspected serial killer – last woman hanged publicly in London, at Newgate in 1862[74][75]

Legacy

[edit]The Central Criminal Court – known as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands – now stands upon the Newgate Prison site.[76]

The original iron gate leading to the gallows was used for decades in an alleyway in Buffalo, New York. It is currently housed in that city at Canisius University.[77]

The original door from a prison cell used to house St. Oliver Plunkett in 1681 is on display at St Peter's Church in Drogheda, Ireland (which also displays his head).[78]

The phrase "[as] black as Newgate's knocker" is a Cockney reference to the door knocker on the front of the prison.[79][80]

In literature

[edit]A record of executions conducted at the prison, together with commentary, was published as The Newgate Calendar.[81]

The prison appears in a number of works by Charles Dickens. Novels include Little Dorrit, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of 'Eighty and Great Expectations. Newgate prison was also the subject of an entire essay in his work Sketches by Boz.[82]

In song

[edit]The Australian "Convict's Rum Song" mentions Newgate with a line reading: [I'd] ... even dance the Newgate Hornpipe If ye'll only gimme Rum!.[83] The 'Newgate Hornpipe' refers to execution by hanging.[84][85]

Gallery

[edit]-

A door from the prison c. 1780, now in the collection of the Museum of London

-

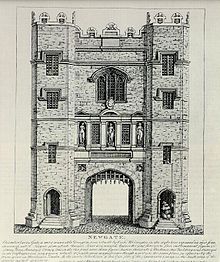

The second Newgate Prison: A West View of Newgate (c. 1810) by George Shepherd

-

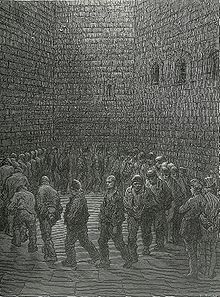

A cell and the galleries at Newgate in 1896

-

Newgate Execution bell, now in the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c Halliday, Stephen (2007). Newgate: London's Prototype of Hell. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3896-9.

- ^ Victoria County History. A history of the County of Middlesex. Vol. 2. pp. 15–60. Paragraph 12. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Bassett, Margery (1943). "Newgate Prison in the Middle Ages". Medieval Academy of America. 18 (2): 233–246. doi:10.2307/2850646. JSTOR 2850646. S2CID 162217628.

- ^ a b Barron, Caroline (2004). London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People, 1200–1500. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 164–166. ISBN 978-0199284412.

- ^ a b c d Ackroyd, Peter (2000). London: The Biography. New York: Nan A. Talese. ISBN 978-0385497718.

- ^ "Background – Prisons and Lockups – London Lives". www.londonlives.org. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 697.

- ^ Buckland, Stephen. "The Newgate Prison Windmill". The Mills Archive. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 by Rupert Gunnisp.129

- ^ "Design for Newgate prison". The Layton Collection. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Britton, John; Pugin, A. (1828). Illustrations of the Public Buildings of London: With Historical and Descriptive Accounts of each Edifice. Vol. 2. London. pp. 102 et seq.

- ^ "Elizabeth Fry". Quakers in the World. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "A Pictorial and Descriptive Guide to London and Its Environs With Two Large Section Plans of Central London". Ward, Lock and Company. 1919. p. 218.

- ^ "Browse - Central Criminal Court". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- ^ Bassett, Margery (1 April 1943). "Newgate Prison in the Middle Ages". Speculum. 18 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 233–246. doi:10.2307/2850646. JSTOR 2850646. S2CID 162217628. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Tim Wales, 'Lorrain, Paul (d. 1719), Church of England clergyman and criminal biographer', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, June 2008

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 January 2018). "'Strike, man, strike!' – On the trail of London's most notorious public execution sites". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Tuer, Andrew (1887). The Follies and Fashions of Our Grandfathers (1807). Field & Tuer. p. 34-36. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Cook, Matt (2007). Mills, Robert; Trumback, Randolph; Cocks, Harry (eds.). A Gay History of Britain: Love and Sex Between Men Since the Middle Ages. Greenwood World Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 978-1846450020.

- ^ A Dictionary of Irish History, D.J. Hickey & J.E. Doherty, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 1980. p 26. ISBN 0-7171-1567-4

- ^ "The secret world of the Old Bailey". BBC. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Bard, Robert (2016). Capital Punishment: London's Places of Execution. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445667379.

- ^ Britain's Official Hangman Quits After 23 Years Without Excuses, in the Evening Star (via Chronicling America); published March 29, 1924

- ^ Mark Jones, Peter Johnstone (22 July 2011). History of Criminal Justice. Elsevier. ISBN 9781437734911. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Keily, Jackie (9 March 2016). "Death masks of the Crime Museum". Museum of London. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Hanham, A. A. "Bambridge, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1255. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Bambridge on trial for murder by a committee of the House of Commons / engraved by T. Cook from an original painting by Wm. Hogarth in the possession of Mr. Ray". Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Palk, Deirdre; Hitchcock, Tim; Howard, Sharon; Shoemaker, Robert. "George Barrington 1755–1804". London Lives, 1690–1800 – Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis. London Lives. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ Pike, Douglas, ed. (1966). "George Barrington (1755–1804)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "The assassin: John Bellingham". UK Parliament. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1885). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 04. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Taaffe, Thomas (1907). "Robert Blackburne". CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Robert Blackburne. The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Rounding, Virginia. The Burning Time: Henry VIII, Bloody Mary, and the Protestant Martyrs of London. 2017. Page 287.

- ^ a b Holzwarth, Larry (16 April 2019). "18 Inhumane and Notorious Prisons in History". Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Griffiths, A. (1884). The chronicles of Newgate. London: Chapman and Hall, pp. 473–474.

- ^ "Neither Single nor Alone: Elizabeth Cellier, Catholic Community, and Transformations of Catholic Women's Piety". Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature. 1 March 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Hopkins, Paul; Handley, Stuart (2004). "Oxford DNB article: Chaloner, William (subscription needed)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66841. Retrieved 10 October 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Clay, Marcy [alias Jenny Fox] (d. 1665), highwaywoman and thief". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73926. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 24 April 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Dyke, Ian (2004). "Oxford DNB article: Cobbett, William (subscription needed)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5735. Retrieved 10 October 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Laurence, John (1932). A history of capital punishment: with special reference to capital punishment in Great Britain. S. Low, Marston & Co. p. 125.

- ^ "Ordinary's Account". Proceedings of the Old Bailey. 4 May 1763. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ König, Eva (2014), "Moll Flanders and Fluid Identity", The Orphan in Eighteenth-Century Fiction: The Vicissitudes of the Eighteenth-Century Subject, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 25–38, doi:10.1057/9781137382023_3, ISBN 978-1-137-38202-3, retrieved 31 October 2021

- ^ Backscheider, Paula R. (May 1988). "No Defense: Defoe in 1703". Publications of the Modern Language Association. 103 (3). Modern Language Association: 274–284. doi:10.2307/462376. ISSN 0030-8129. JSTOR 462376. S2CID 163284949 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Transport in Slough: Claude Duval - Gentleman Highwayman". Slough History Online. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Rose, Lionel (1986). Massacre of the Innocents: Infanticide in Britain, 1800–1939. Routledge. p. 161.

- ^ "Chapter 9. Daniel Isaac Eaton, Extortions and Abuses of Newgate; Exhibited in a Memorial and Explanation, Presented to the Lord Mayor". London. 1813.

- ^ "A boke made by John Frith, prisoner in the Tower of London : answeringe vnto M Mores lettur, which he wrote agenst the first litle treatyse that John[n] Frith made concerninge the sacramente of the Body and Bloude of Christ : vnto which boke are added in the ende the articles of his examinacion before the bishoppes of London, Winchestur and Lincolne, in Paules Church at London, for which John Frith was condempned a[n]d after bure[n]t in Smith felde with out Newgate, the fourth daye of Juli, anno 1533".

- ^ "MARY FRITH OTHERWISE MOLL CUTPURSE, A famous Master-Thief and an Ugly, who dressed like a Man, and died in 1663". The Newgate Calendar, Part II (1742 to 1799). Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Haydon, Colin (2004). "Oxford DNB article: Gordon, Lord George (subscription needed)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11040. Retrieved 3 June 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Lesley Nelson-Burns. "Jack Hall". Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Ward, Adolphus William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 502–507.

- ^ Jorgenson, Jorgen (1827). The Religion of Christ is the Religion of Nature. Written in the Condemned Cells of Newgate. London.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (1 May 2001). "Execution of Captain Kidd". History Today.

- ^ Adams, Gavin John (2012). Letters to John Law. Newton Page. pp. xiv, xxi, liii. ISBN 978-1-934619-08-7.

- ^ "British Executions - Thomas Kingsmill - 1749". British Executions.

- ^ Foight, Michael (11 April 2011). "A View from Behind Bars: The Diary of Thomas Lloyd, Revolutionary and Father of American Shorthand, from Newgate Prison 1794–1796". Falvey Memorial Library Blog. Villanova University. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ "Death of a highwayman: Captain James Maclaine". Stair na hÉireann. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Sutton, Anne F. (1 September 2000). "Malory in Newgate: A New Document". The Library. 1 (3): 243–262. doi:10.1093/library/1.3.243.

- ^ "News". The Times. No. 1324. 19 March 1789. p. 3.

- ^ "Corbett's Complete Collection of State Trials". T. C. Hansard. 1811. p. 1079.

- ^ Kenyon, J.P. The Popish Plot Phoenix Press Reissue 2000, p. 150

- ^ Anne Roper. The Church of Saint Augustine, Brookland. 25th edition, 1979. Page 28–29.

- ^ Ryle, The Rev. Canon (1872). "John Rogers, the Proto-Martyr". In Bickersteth, Rev. E. H. (ed.). Evening Hours: A Church of England Magazine, Volume II—1872. London: William Hunt and Company. pp. 690–691. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Defoe, Daniel. The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard. London: 1724. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Sharman, R. C. (1967). "Isaac (Ikey) Solomon (1787–1850)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 2. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- ^ Hurley, J. (1 September 1928). "The Venerable Robert Southwell Poet and Martyr (1560-1595). III". The Irish Monthly. 56 (663): 472–479. JSTOR 20518390.

- ^ Duffield, Ian; Bradley, James (1997). Representing Convicts: New Perspectives on Convict Forced Labour Migration. Leicester University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0718500757.

- ^ "1684: Jane Voss, narrow escapee". Executed Today. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "1789: Not Mary Wade, 11-year-old thief". Executed Today. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Fairburn, Miles. "Wakefield, Edward Gibbon". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Wall, Joseph". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Hugh Chisholm (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Housden, Martyn (25 October 2006). "Oscar Wilde's imprisonment and an early idea of "Banal Evil" or Two "wasps" in the system. How Reverend W.D. Morrison and Oscar Wilde challenged penal policy in late Victorian England". Forum Historiae Iuris. Legal History Forum: 31.

- ^ Beadle, Jeremy; Harrison, Ian (2008). Firsts, Lasts & Onlys Crime. Anova Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-905798-04-9.

- ^ "Murder Cases – Female W – Wilson, Catherine". Real Crime. Archived from the original on 11 February 2005.

- ^ "Old Bailey". E-Architect. 22 June 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "1966-1990: Protest, Promise and Progress". Canisius. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Ireland: Red Wednesday Reflection by Archbishop Eamon Martin". Independent Catholic News. 25 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ "As Black as Newgate's Knocker". www.peterberthoud.co.uk. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "As black as newgates knocker in The AnswerBank: Phrases & Sayings". www.theanswerbank.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Facts about the Newgate Calendar". The British Library. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "'A Visit to Newgate', from Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz". British Library. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (2010). The Fatal Shore. London: Penguin. p. 292. ISBN 9781407054070.

- ^ A Dictionary of Slang and Colloquial English by John Stephen Farmer (G. Routledge & Sons, Limited, 1921), page 305.

- ^ Holgate, Andrew (13 July 2008). "The Gaol: The Story of Newgate, London's Most Notorious Prison by Kelly Grovier". Times. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Babington, Anthony. "Newgate in the Eighteenth Century" History Today (Sept 1971), Vol. 21 Issue 9, pp 650–657 online.

- Halliday, Stephen (2007), Newgate: London's Prototype of Hell, The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7509-3896-9

External links

[edit]- Newgate Prison

- 1188 establishments in England

- 1903 disestablishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1188

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1777

- Defunct prisons in London

- Former buildings and structures in the City of London

- Demolished buildings and structures in London

- Debtors' prisons

- Demolished prisons

- Buildings and structures demolished in 1903

- Windmills in London

- Henry II of England