Isaaq

| Isaaq Reer Sheekh Isxaaq بنو إسحاق | |

|---|---|

| Somali clan | |

The tomb of Ishaaq, the father of the Isaaq clan, in Maydh | |

| Ethnicity | Somali |

| Location | |

| Descended from | Sheikh Ishaaq bin Ahmed |

| Population | 3-4 million[2] |

| Branches | Habr Magaadle:

Habr Habuusheed: |

| Language | Somali Arabic |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

The Isaaq (Somali: Reer Sheekh Isxaaq, Arabic: بنو إسحاق, Banu Ishaq) is a major Somali clan.[3] It is one of the largest Somali clan families in the Horn of Africa, with a large and densely populated traditional territory.

The Isaaq people claim in a traditional legend to have descended from Sheikh Ishaaq bin Ahmed, an Islamic scholar who purportedly traveled to Somaliland in the 12th or 13th century and married two women; one from the local Dir clan. and the other from the neighboring Harari people.[4] He is said to have sired eight sons who are the common ancestors of the clans of the Isaaq clan-family. He remained in Maydh until his death.[5]

Overview

Somali genealogical tradition places the origin of the Isaaq tribe in the 12th or 13th century with the arrival of the Sheikh Ishaaq Bin Ahmed (Sheikh Ishaaq) from Arabia.[6][7] Sheikh Ishaaq settled in the coastal town of Maydh in modern-day northeastern Somaliland.Hence, Sheikh Ishaaq married two local women in Somaliland, which left him with eight.[4][8]

There are also numerous existing hagiographies in Arabic which describe Sheikh Ishaaq's travels, works and overall life in modern Somaliland, as well as his movements in Arabia before his arrival.[9] Besides historical sources, one of the more recent printed biographies of Sheikh Ishaaq is the Amjaad of Sheikh Husseen bin Ahmed Darwiish al-Isaaqi as-Soomaali, which was printed in Aden in 1955.[10]

Sheikh Ishaaq's tomb is in Maydh, and is the scene of frequent pilgrimages.[9] Sheikh Ishaaq's mawlid (birthday) is also celebrated every Thursday with a public reading of his manaaqib (a collection of glorious deeds).[4] His Siyaara or pilgrimage is performed annually both within Somaliland and in the diaspora particularly in the Middle East among Isaaq expatriates.[11]

The dialect of the Somali language that the Isaaq speak has the highest prestige of any other Somali dialect.[12]

Distribution

The Isaaq have a very wide and densely populated traditional territory and make up 80% of Somaliland's population,[13][14] and

|

| Part of a series on |

| Somali clans |

|---|

live in all of its six regions (Awdal, Marodi Jeh, Togdheer, Sahil, Sanaag and Sool). The Isaaq have large settlements in the Somali Region of Ethiopia, mainly on the eastern side of Somali Region also known as the Hawd and formerly Reserve Area which is mainly inhabited by the Isaaq residents. A subclan of the Habr Yunis, the Damal Muse (also known as the Dir Rooble[15]), also inhabit the Mudug region of Somalia.[16] The Habarnoosa, a clan of the Hadiya people in the Hadiya Zone claim descent from the Habr Yunis subclan of Isaaq.[17] The Isaaqs also have large settlements in Naivasha, Kenya, where the Ishaakia make up a large percentage of the Kenyan population, and in Djibouti, where the Isaaq is the fourth largest group after the Issa, the Afar, and the Gadabuursi, accounting for 20% of Djibouti's population.[18] The Isaaq are estimated to number 3-4 million according to a 2015 estimate.[19]

The Isaaq tribe are the largest group in Somaliland. The populations of five largest cities in Somaliland – Hargeisa, Burao, Berbera, Erigavo and Gabiley – are all predominantly Isaaq.[20][21][22] They exclusively dominate the Marodi Jeh region, and the Togdheer region, and form a majority of the population inhabiting the western and central areas of Sanaag region, including the regional capital Erigavo.[23] The Isaaq also have a large presence in the western and northern parts of Sool region as well,[24] with Habr Je'lo sub-clan of Isaaq living in the Aynabo district whilst the Habr Yunis subclan of Garhajis lives in the eastern part of Xudun district and the very western part of Las Anod district.[25] They also live in the northeast of the Awdal region, with Saad Muse sub-clan being centered around Lughaya and its environs. THE Arap live Somalia Bakool Rabdhure District the live also Fafan Zone and Baligubadle.[citation needed]

The Isaaq also has a sizable diaspora around the world, mainly residing in Western Europe, the Middle East, North America, and several other African countries.[26][27] The Isaaq were among the first Somalis to arrive in the United Kingdom in the 1880s, and have since then formed large communities across the country, especially in Cardiff,[28] Sheffield,[29] Bristol and eastern London boroughs like Tower Hamlets and Newham.[30][31] In Canada the Isaaq form large communities in the North York and Scarborough districts of Toronto.[32]

History

Medieval

As the Isaaq grew in size and numbers during the 12th century, the clan-family migrated and spread from their core area in Mait (Maydh) and the wider Sanaag region in a southwestward expansion over a wide portion of present-day Somaliland by the 15th and 16th centuries.[33][34][35][36] By the 1300s the Isaaq clans united to defend their inhabited territories and resources during clan conflicts against migrating clans.[19]

The Isaaq played a prominent role in the Ethiopian-Adal War (1529–1543, referred to as the "Conquest of Abyssinia") in the army of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi,[37] The Habr Magadle division (Ayoub, Garhajis, Habr Awal and Arap) of the Isaaq were mentioned in chronicles of that war written by Shihab Al-Din Ahmad Al-Gizany known as Futuh Al Habash.[38]

I. M. Lewis states:[39]

The Marrehan and the Habr Magadle [Magādi] also play a very prominent role (...) The text refers to two Ahmads's with the nickname 'Left-handed'. One is regularly presented as 'Ahmad Guray, the Somali' (...) identified as Ahmad Guray Xuseyn, chief of the Habr Magadle. Another reference, however, appears to link the Habr Magadle with the Marrehan. The other Ahmad is simply referred to as 'Imam Ahmad' or simply the 'Imam'.This Ahmad is not qualified by the adjective Somali (...) The two Ahmad's have been conflated into one figure, the heroic Ahmed Guray (...)

Early modern

Long after the collapse of the Adal Sultanate, the Isaaq established successor states, the Isaaq Sultanate and the Habr Yunis Sultanate.[40] These two Sultanates possessed some of the organs and trappings of a traditional integrated state: a functioning bureaucracy, regular taxation in the form of livestock, as well as an army (chiefly consisting of mounted light cavalry).[41][42][43][44] These sultanates also maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.[45] The Isaaq Sultanate ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries and spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch of the Eidagale clan and is the pre-colonial predecessor to the modern Republic of Somaliland.[46][47][48]

The modern Guled Dynasty of the Isaaq Sultanate was established in the middle of the 18th century by Sultan Guled of the Eidagale line of the Garhajis clan. His coronation took place after the victorious battle of Lafaruug in which his father, a religious mullah Abdi Eisa successfully led the Isaaq in battle and defeated the Absame tribes near Berbera where a century earlier the Isaaq clan expanded into. After witnessing his leadership and courage, the Isaaq chiefs recognized his father Abdi who refused the position instead relegating the title to his underage son Guled while the father acted as the regent till the son come of age. Guled was crowned the as the first Sultan of the Isaaq clan in July 1750.[49] Sultan Guled thus ruled the Isaaq up until his death in 1839, where he was succeeded by his eldest son Farah full brother of Yuusuf and Du'ale, all from Guled's fourth wife Ambaro Me'ad Gadid.[47]

By the early 1880s the Isaaq Sultanate had been reduced to the Ciidangale confederation with the Eidagale, and Ishaaq Arreh subclan of the Habr Yunis remaining. In 1884–1886 the British signed treaties with the coastal subclans and had not yet penetrated the interior in any significant way.[50] Sultan Deria Hassan remained de facto master of Hargeisa and its environs.

Modern

Dervish movement

The Isaaq also played a major role in the Dervish movement, with Sultan Nur Aman of the Habr Yunis being fundamental in the inception of the movement. Sultan Nur was the principle agitator that rallied the dervish behind his anti-French Catholic Mission campaign that would become the cause of the dervish uprise.[51] Haji Sudi of the Habr Je'lo was the highest ranking Dervish after Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, he died valiantly defending the Taleh fort during the RAF bombing campaign.[52][53][54] The Isaaq tribes most well known for joining the Dervish movement were from the eastern tribes such as the Habr Yunis and Habr Je'lo. These two sub-tribes were able to purchase advanced weapons and successfully resist both British Empire and Ethiopian Empire for many years.[55] The fourth Isaaq Grand Sultan Deria Hassan exchanged letters with Muhammad Abdullah Hassan in the first year of the movement's foundation, with the sultan inciting an insurrection in Hargeisa in 1900 as well as supplying the Mullah with vital information.[56]

Post-colonial

The Isaaq people along with other northern Somali tribes were under British Somaliland protectorate administration from 1884 to 1960. On gaining independence, the Somaliland protectorate decided to form a union with Italian Somalia. The Isaaq clan spearheaded the greater Somalia quest from 1960 to 1991.

The Isaaq played a massive role to push for unification and independence. They selected to join the Trust Territory of Somaliland to form the Somali Republic. During the civilian government from 1960 to 1969, they held dominant positions. Jama Mohamed Ghalib (1960-4) and Ahmed Mohamed Obsiye (1964-6), both belonging to the Isaaq clan, served as the president of the National Assembly, while a notable Isaaq member named Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal served as the prime minister of Somalia from 1967 to 1969. Furthermore, when English became one of the official languages, the ministries of Foreign Trade, Foreign Affairs, Education, and Information were mainly held by the Isaaq members. They were still powerful in the early years of the military dictatorship (1969–91). However, from the late 1970s, Marehan became politically powerful under the leadership of the military dictator Siad Barre. The Isaaq began to face political and economic marginalization and in response, they organized the Somali National Movement to over his regime. Thus the Somaliland War of Independence began and this struggle movement forced the Isaaq clan to become a victim to a genocidal campaign by Siad Barre's troops (which also included armed Somali refugees from Ethiopia); the death toll has been estimated to be between 50,000 and 250,000. After the collapse of the Somali Democratic Republic in 1991 the Isaaq-dominated Somaliland declared independence from Somalia as a separate nation.[57][58]

Mercantilism

Historically (and presently to a degree), the wider Isaaq clan were relatively more disposed to trade than their tribal counterparts due in part to their centuries-old trade links with the Arabian Peninsula. In view of this imbalance in mercantile experience, other major Somali clans tended to resort to tribal slang terms such as "iidoor", an enviable pejorative roughly meaning trader/exchanger:

Somalis bandied about numerous stereotypes of clan behavior that mirrored these emerging social inequalities. The pejorative slang terms iidoor or kabadhe iidoora (loosely meaning "exchange") reflect Somali disdain for the go-between, the person who amasses wealth through persistence and mercantile skills without firm commitments to anyone else. As the Isaaq became more international and cosmopolitan, their commercial success and achievement ideology aroused suspicion and jealousy, notably among rural Darod who disliked Isaaq self-confidence and made them the target of stereotypes.[59]

The Habr Awal clan of the Isaaq have a rich mercantile history largely due to their possession of the major Somali port of Berbera, which was the chief port and settlement of Habr Awal clan during the early modern period.[60] The clan had strong ties to the Emirate of Harar and Emirs would hold Habr Awal merchants in their court with high esteem with Richard Burton noting their influence in Emir Ahmad III ibn Abu Bakr's court and discussions with the Vizier Mohammed.[61] The Habr Awal merchants had extensive trade relations with Arab and Indian merchants from Arabia and the Indian subcontinent respectively,[62] and also conducted trade missions on their own vessels to the Arabian ports.[63] Berbera, in addition to Berbera being described as “the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf,[64] was also the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as livestock, coffee, frankincense, myrrh, acacia gum, saffron, feathers, wax, ghee, hide (skin), gold and ivory.[65]

The Habr Je'lo clan of the Isaaq derived a large supply of frankincense from the trees south in the mountains near port town of Heis. This trade was lucrative and with gum and skins being traded in high quantity, Arab and Indian merchants would visit Habr Je'lo ports early in the season to get these goods cheaper than at Berbera or Zeyla before continuing westwards along the Somali coast.[66] Heis, in addition to being a leading exporter of tanned skins also exported a large quantity of skins and sheep to Aden as well as imported a significant amount of goods from both the Arabian coast and western Somali ports, reaching nearly 2 million rupees by 1903.[67] The Habr Je’lo coastal settlements and ports, stretching from near Siyara in the west to Heis (Xiis) in the east, were important to trade and communication with the Somali interior, with Kurrum (Karin), the principle Habr Je’lo port, being a major market for livestock and frankincense procured from the interior,[68] and was a favorite for livestock traders due to the close proximity of the port to Aden. The Buur Dhaab range in Sool region has also historically acted as a junction for trade caravans coming from the east on their way to Berbera port,[69] passing through the Laba Gardai or Bah Lardis pass located within the range.[70] The powerful Habr Je'lo clan has historically acted as the guardians of this pass, receiving dues in exchange for guaranteed safety through Buur Dhaab:[69]

The Habr Toljaala are a powerful tribe, and make it a point of honour that caravans shall have safe passage through their country, and they receive a part of the dues for this purpose.

Starting in the middle of the 19th century, Isaaq clans became more connected to the European commercial world as historic ties between southern Somali towns along the Benadir coast with India and Oman were being reoriented southward toward Zanzibar.[71] Isaaq trade and migration patterns were skewed by British imperial control of Aden more toward Europe and colonies like India, Egypt, and the Sudan, enabling the Isaaq to maintain a variety of contacts across the British Empire.[71] The Isaaq clan-family became the first Somalis to actually reside abroad, in western Europe or its colonial outposts, where they socialized in two different cultures.[71]

The Isaaq affinity for mercantilism was not lost on the sole president and dictator of the Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1991), Siad Barre, who disliked the Isaaq clan-family due to their financial independence, thus making it harder to control them:

Siyaad had a deep and personal dislike for the clan. The real reasons can only be guessed at, but in part it was due to his inability to control them. As accomplished business operatives, they had built a society that was not dependent on government largesse. The Isaaq had traditional trade relationships with the nations of the Arabian Peninsula that continued despite the attempts of the government to center all economic activity in Mogadishu. Siyaad did what he could, however, and Isaaq traders were forced to make the long trip to Mogadishu for permits and licenses.[72]

Nevertheless, in the 1970s and 1980s, nearly all of the livestock exports went out through the port of Berbera via Isaaq livestock traders, with the towns of Burao and Yirowe in the interior being home to the largest livestock markets in the Horn of Africa.[73][74][75] The entire livestock exports accounted to upwards of 90% of the Somali Republic's entire export figures in a given year, and Berbera's exports alone provided over 75% of the nation's recorded foreign currency income at the time.[76][77]

Isaaq sub-clans

In the Isaaq clan, component sub-clans are divided into two uterine divisions, as shown in the genealogy. The first division is between those lineages descended from sons of Sheikh Ishaaq by a Harari woman – the Habr Habuusheed – and those descended from sons of Sheikh Ishaaq by a Somali woman of the Magaadle sub-tribe of the Dir – the Habr Magaadle. Indeed, most of the largest subtribes of the tribal-ethnic group are in fact uterine alliances hence the matronymic "Habr" which in archaic Somali means "mother".[78] This is illustrated in the following clan structure.[79]

A. Habr Magaadle

- Abdirahman (Habr Awal)

- Muhammad (Arap)

- Muuse celi Barsuug

- Maxamed celi

- Subeer celi

- Ayub

- Ismail (Habr Garhajis)

B. Habr Habuusheed

- Ahmed (Tol Je’lo)

- Muuse (Habr Je'lo)

- Ibrahiim (Sanbuur)

- Muhammad (‘Ibraan)

There is clear agreement on the tribe and sub-tribe structures that has not changed for a long time. The oldest recorded genealogy of a Somali in Western literature was by Sir Richard Burton in the mid–19th century regarding his Isaaq (Habr Yunis) host and the governor of Zeila, Sharmarke Ali Saleh[80]

The following listing is taken from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001.[81][82]

- Isaaq

- Habr Awal

- Arap

- Muuse celi Barsuug

- Maxamed celi

- Subeer celi

- Ayub

- Garhajis

- Habr Je'lo

- Muuse Abokor

- Mohamed Abokor

- Samane Abokor

- Tol Je'lo

- Sanbuur

- Imraan

Stereotypes among the Isaaq subtribes go a long way to explaining each subtribes role in Somaliland.[83][84] In one exemplified folklore tale, Sheikh Ishaaq's three eldest sons split their father's inheritance among themselves.[83] Garhajis receives his imama, a symbol of leadership; Awal receives the sheikh's wealth; and Ahmed (Tolja'ele) inherits his sword.[83] The story is intended to depict the Garhajis's proclivity for politics, the Habr Awal's mercantile prowess, and the Habr Je'lo's bellicosity.[83]

To strengthen these tribal stereotypes, historical anecdotes have been used: The Garhajis were dominant leaders before and during the colonial period, and thus acquired intellectual and political superiority; Habr Awal dominance of the trade via Djibouti and Berbera is practically uncontested; and Habr Je’lo military prowess is cited in accounts of previous conflicts.[83]

Notable figures

Royalty and rulers

- Deria Hassan, 4th Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Abdillahi Deria, 5th Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Guled Abdi, 1st Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Awad Deria, 5th Sultan of the Habr Yunis

- Deria Sugulleh Ainashe, 2nd Sultan of the Habr Yunis

- Hersi Aman, 3rd Sultan of the Habr Yunis

- Sharmarke Ali Saleh, major trader and governor of Berbera, Zeila and Tadjoura

- Farah Guled, 2nd Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah - Sultan of the Arap clan and commander of the SNM's 10th division

- Sultan Abdulrahman Deria, Sultan of the Habr Awal clan

- Sultan Abdillahi Deria, prominent anti-colonial figure and 5th Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Mahamed Abdiqadir – 8th Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Madar Hersi, 7th Sultan of the Habr Yunis Sultanate

- Daud Mahamed, 9th and current Grand Sultan of the Isaaq

- Sultan Osman Sultan Ali Koshin, the current Grand sultan of the Issa Musse clans

- Sugulle Ainanshe, 1st Sultan of the Habr Yunis

Politicians

- Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, former president of Somaliland from June 2010 to December 2017, fourth and longest-serving chairman of the Somali National Movement, and former chairman of the Kulmiye Party

- Muse Bihi Abdi, current president of Somaliland

- Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur, last Somali National Movement chairman and first president of Somaliland

- Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi, Speaker of the House of Representatives of Somaliland and the chairman of Wadani political party

- Ahmed Yusuf Yasin, was the vice-president of Somaliland from 2002 until 2010. and the second chairman of UDUB party.

- Abdurrahman Mahmoud Aidiid, former mayor of Hargeisa, the capital of the Somaliland

- Abdikarim Ahmed Mooge, former mayor of Hargeisa

- Ali Abdi Farah, former minister of communication and culture in Djibouti

- Ali Ismail Yacqub - first minister of defence for the Somali Republic

- Abdirahim Abbey Farah, former United Nations under-secretary general

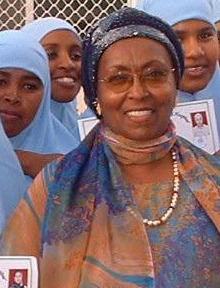

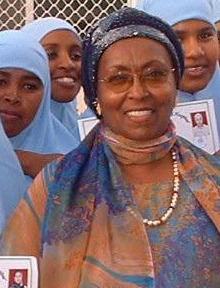

Edna Adan Ismail, nurse midwife, activist and the first female foreign minister of Somaliland from 2003 to 2006 - Umar Arteh Ghalib, former prime minister of Somalia 1991–1993. Brought Somalia into the Arab League in 1974 during his term Foreign Minister of Somalia from 1969 to 1977. Former president of UN Security Council, teacher and poet

- Hussein Arab Isse, the Minister of Defence and the deputy prime minister of Somalia from 20 July 2011 to 4 November 2012

- Ismail Mahmud Hurre, foreign minister of the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia from mid-2006 to early 2007

- Ismail Ali Abokor, former vice-president of the Somali Democratic Republic[85]

- Faysal Ali Warabe, chairman of the For Justice and Development party of Somaliland (UCID).

- Fowsiyo Yusuf Haji Adan, former foreign minister of Somalia and MP in Federal Parliament

- Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, former prime minister of Somalia July 1960, July 1967– November 1969; former president of Somaliland from May 1993 to May 2002.

- Mohamed Abdullahi Omaar, former foreign minister of Somalia

- Mohamed Omar Arte, former deputy prime minister of Somalia.

- Abdishakur Iddin, current mayor of Berbera

- Abdirisaq Ibrahim Abdi, current mayor of Burao

- Jama Mohamed Ghalib, former Police Commissioner of the Somali Democratic Republic, Secretary of Interior, Minister of Labor and Social Affairs, Minister of Local Government and Rural Development, Minister of Transportation, and Minister of Interior.

- Osman Dubbe – Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism of Somalia

- Mohamed Ainanshe Guled, former military officer and vice president of the Somali Democratic Republic[86][87]

- Muhammad Hawadle Madar, former prime minister of Somalia from 3 September 1990 to 24 January 1991

- Ismail Ali Abokor – Vice President of the Somali Democratic Republic 1971–1982

- Abdilahi Husein Iman Darawal - Somaliland politician and former SNM commander

- Abdullahi Abdi Omar "Jawaan" - Somaliland politician and introducer of the National emblem of Somaliland

- Mohamed Abdullahi Omaar, served twice as the Foreign Minister of Somalia.

- Osman Jama Ali - Prime Minister of Somalia under the Transitional National Government

- Salah Ahmed Jama - Current Deputy Prime Minister of the Federal Government of Somalia

- Hussein Mohamed Bashe - Current Minister of Agriculture of Tanzania

Poets

- Salaan Carrabey – legendary poet

- Abdillahi Suldaan Mohammed Timacade, known as 'Timacade', a famous poet during the pre- and post-colonial periods

- Mohamed Hashi Dhamac (Gaarriye), legendary Somali poet and political activist

- Hadrawi, poet and philosopher; author of Halkaraan; also known as the "Somali Shakespeare"

- Elmi Boodhari, legendary and beloved poet and pioneer for many Somali poetry/music genres, specifically romance and is dubbed the "King of Romance

- Hussein Hasan - legendary warrior and poet and was the grandson of the 1st Isaaq Sultan Guled Abdi

- Farah Nur, a famous warrior, poet and sultan of the Arap subclan[88]

- Hussein Hasan - legendary warrior and poet and was the grandson of the 1st Isaaq Sultan Guled Abdi

- Kite Fiqi – legendary Habr Je'lo warrior and poet

- Aden Ahmed Dube of the Isaaq, Habr-Yonis tribe, great poems aroused envy in Raage Ugaz, and infrequently, bloody wars and irreconcilable enmity.

- Mohammed Liban from the Isaaq tribe of Habr Awal, was an eloquent and witty improviser, and even better known under the name of Mohammed Liban Giader.[89]

- Aden Ahmed Dube "Gabay Xoog" circa 1821 –1916, poet.[90][91]

- Abdiwaasa' Hasan Ali Araale Guleid, wellknown poet

- Abdi Iidan Farah, 20th century Somali poet who wrote about Somali independence and camels

Economists

- Abdul Majid Hussein, Economist, former permanent representative of Ethiopia to the United Nations, 2001–2004. Leader of Ethiopian Somali Democratic League (ESDL) party in the Somali Region of Ethiopia from 1995 to 2001

- Jamal Ali Hussein, Somali politician and economists expert. He was former presidential candidate of Somaliland UCID party[92]

- Dr. Saad Ali Shire, British-Somali politician, agronomist and economist, who is currently serving as the Minister of Finance of Somaliland. Shire formerly served as the Foreign Minister of Somaliland. He also served as the Minister of Planning and National Development of Somaliland.

Military leaders and personnel

- Mohamed Dalmar Yusuf Ali, more commonly known as "Mohamed Ali", high-ranking commander of the WSLF and SNM

- Deria Hassan, fourth Grand Sultan of Isaaq, recognised for being a wise and astute leader.

- Mohamed Kahin Ahmed, high-ranking SNM commander and current Minister of Interior of Somaliland

- Guled Haji, wise sage and commander of the Habr Yunis

- Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi, former chief of staff of the Somaliland Armed Forces

- Ibrahim Boghol, high-ranking commander of the Dervish movement

- Nuh Ismail Tani, current chief of staff of the Somaliland Armed Forces

- Mohamed Hashi Lihle - colonel of the SNA and later the commander of the military wing of the Somali National Movement

- Mohamed Bullaleh - prominent 20th-century tribal chief and commander of the Hagoogane raid that destroyed Dervish movement

Writers and musicians

- Abdullahi Qarshe, Somali musician, poet and playwright; known as the "Father of Somali music"

- Ali Feiruz, popular musician in Djibouti, Somaliland and Somalia

- Mohamed Mooge Liibaan, highly renowned Somali instrumentalist and vocalist.

- Ahmed Mooge Liibaan, prominent Somali instrumentalist and vocalist

- Nadifa Mohamed – Somali novelist. Winner of the 2010 Betty Trask Prize

- Chunkz – English YouTuber, musician, host and entertainer

- Ahmed Gacayte – famous Somali singer, songwriter and composer

- Sahra Halgan, Somali singer and cultural activist

- Shamis Abokor Ismail (Guduudo Carwo), Somali singer

Scholars

- Musa Haji Ismail Galal, a Somali writer, scholar, linguist, historian and polymath

- Abdillahi Diiriye Guled - Literary scholar and discoverer of the Somali prosodic system

- Jama Musse Jama, prominent Somali ethnomathematician and author

- Hussein Mohammed Adam (Tanzania) - foremost Somali intellectual and scholar who founded the Somali Studies International Association (SSIA)

Religious leaders and scholars

- Sheikh Bashir, Somali religious leader who waged the 1945 Sheikh Bashir Rebellion

- Sheikh Madar – head of Qadiriyya tariqa and influential figure in the early growth and expansion of Hargeisa

- Abdallah Shihiri, senior advisor to the Mullah of the Dervish movement

- Deria Arale, senior advisor to the Mullah of the Dervish movement

- Haji Sudi, one of the founders of the Somali Dervish movement

- Sheikh Mohamed Sheikh Omar Dirir - prominent religious scholar and businessman

- Sultan Nur Ahmed Aman, Sultan of the Habr Yunis and one of the founders of the Somali Dervish movement

- Ridwan Hirsi Mohamed – Former deputy prime minister of Somalia and former minister of religious affairs of Somalia

- Yasin Handule Wais religious scholar and founder of Somaliland's first Islamic party in the mid-20th century

Entrepreneurs

- Abdirashid Duale, Somali entrepreneur and the CEO of Dahabshiil

- Abdi Awad Ali (Indhadeero) – renowned Somali entrepreneur and founder and former CEO of Indhadeero Group of Companies

- Amina Moghe Hersi (b. 1963), Award-winning Somali entrepreneur who has launched several multimillion-dollar projects in Kampala, Uganda

- Ismail Ahmed, owner and CEO of WorldRemit which is one of the fastest growing money transfer company in the world and he's considered 7th most influential man in Britain.[93]

- Mahmood Hussein Mattan, Somali former merchant seaman who was wrongfully convicted of the murder of Lily Volpert on 6 March 1952

- Ibrahim Dheere, considered to be the first Somali billionaire and richest Somali person in the world with an estimated net worth of 1.8 billion US Dollars.[94]

- Mohammed Abdillahi Kahin 'Ogsadey', Somali business tycoon based in Ethiopia, where he established MAO Harar Horse, the first African corporation to export coffee and amassed a net worth of approximately $3 Billion Ethiopian Birr.[95]

Activists

- Edna Adan Ismail, first female Foreign Minister of Somaliland, has been called "The Muslim Mother Teresa" for her charity work and activism for women and girls

- Michael Mariano – legendary Somali politician, lawyer and key figure in independence struggle and Somali Youth League

- Farah Omar – anti-colonial ideologue and founder of the first Somali Association

- Hassan Isse Jama, one of the founding fathers of the SNM in London, former deputy chairman of SNM, first vice president of Somaliland.[96]

- Hassan Adan Wadadid- One of the original founders of the Somali National Movement and served as the movement's first vice-chairman.

- Hanan Ibrahim, gender activist and first Somali British to be awarded Member of British Empire (MBE) for community work in UK

- Nimco Ali, British social activist

- Magid Magid – Somali-British activist and politician who served as the Lord Mayor of Sheffield from May 2018 to May 2019

Athletes

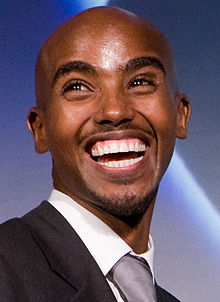

- Mo Farah, British 4 time Olympic gold medalist and the most decorated athlete in British athletics history.[97]

- Mohammed Ahmed, Somali-Canadian long-distance runner and Olympian

- Mohammed Ahamed, Norwegian-Somalian association footballer currently playing in the Tippeligaen for Tromsø IL. He plays as a Center Forward

- Ahmed Said Ahmed, an international footballer who plays for VJS as a defender.[98][99]

- Bashir Abdi, Somali-Belgian athlete

- Sheikh Hamse - notorious Somali football player

Journalists

- Ahmed Hassan Awke, Somali journalist and broadcaster, veteran of the BBC World Service, the Voice of America, Somaliland National TV, Horn Cable Television, Radio Mogadishu and Universal TV, former presidential spokesman of Siad Barre during his military junta.[100]

- Rageh Omaar, Somali-British journalist and writer. He used to be a BBC world affairs correspondent, In September 2006, he moved to a new post at Al Jazeera English, and as of 2017 is currently with ITV News

- Mona Kosar Abdi – news anchor for ABC's Good Morning America

Other

- Hussain Bisad, is one of the tallest men in the world, at 2.32 m (7 ft 7 1⁄2 in). He has the largest hand span of anyone alive

- Sada Mire, Swedish-Somali archaeologist, art historian and presenter

- Abdi Haybe Lambad, famous Somali stand-up comedian

- Buurmadow – well known clan elder

- Hussein Mohammed Adam "Tanzania", Somali professor, journalist and documentary maker

- Sooraan, famous actor and comedian[101]

References

- ^ Renders, Marleen (27 January 2012). Consider Somaliland: State-Building with Traditional Leaders and Institutions. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-22254-0.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (1 August 2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 184–185. ISBN 979-8-216-14892-0.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1994). Blood and Bone: The Call of Kinship in Somali Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780932415936.

isaaq noble.

- ^ a b c I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), pp. 31 & 42

- ^ Adam, Hussein M. (1980). Somalia and the World: Proceedings of the International Symposium Held in Mogadishu on the Tenth Anniversary of the Somali Revolution, October 15–21, 1979. Halgan.

- ^ Berns McGown, Rima (1999). Muslims in the diaspora. University of Toronto Press. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (2002). A Modern History of the Somali (Fourth ed.). Oxford: James Currey. p. 22.

- ^ Gori, Alessandro (2003). Studi sulla letteratura agiografica islamica somala in lingua araba [Studies on Somali Islamic hagiographic literature in Arabic] (in Italian). Firenze: Dipartimento di linguistica, Università di Firenze. p. 72. ISBN 88-901340-0-3. OCLC 55104439. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ a b Roland Anthony Oliver, J. D. Fage, Journal of African history, Volume 3 (Cambridge University Press.: 1962), p.45

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 131.

- ^ Reese, Scott S. (2018). "Claims to Community". Claims to Community: Mosques, Cemeteries and the Universe. Islam, Community and Authority in the Indian Ocean, 1839–1937. Edinburgh University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-7486-9765-6. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1tqxt7c.10. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Pia, John Joseph (1968). Somali Sounds and Inflections. Indiana University Press. p. 6.

- ^ Wiafe-Amoako, Francis (2018). Africa. 2018-2019, 53rd edition. Lanham, MD. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4758-4179-4. OCLC 1050870928.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Somaliland between clans and November elections". New Internationalist. 2017. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Abtirsi.com : Damal "Dir Roble" Muse Arre". www.abtirsi.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Mataan, Asad Cabdullahi (28 November 2012). "Qabaa'ilka Soomaalidu ma isbahaysi baa, mise waa dhalasho?". Caasimada Online. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- ^ Zeitschrift für Ethnologie (in German). Springer-Verlag. 1957. pp. 71, 75. Archived from the original on 18 August 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "Somalia: Information on the Issa and the Issaq". Refworld. Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Canada. 1 March 1990. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b Minahan, James B. (1 August 2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 184–185. ISBN 979-8-216-14892-0.

- ^ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Somalia: Information on the ethnic composition in Gabiley (Gebiley) in 1987–1988 Archived 22 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine, 1 April 1996, SOM23518.E [accessed 6 October 2009]

- ^ Tekle, Amare (1994). Eritrea and Ethiopia: From Conflict to Cooperation. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 9780932415974. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Briggs, Philip (2012). Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-84162-371-9. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Report on the Fact-finding Mission to Somalia and Kenya (27 October – 7 November 1997)". Refworld. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "Beyond Fragility: A Conflict and Education Analysis of the Somali Context" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "EASO Country of Origin Information Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Member Profile Somaliland: Government of Somaliland" (PDF). Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: 4. January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 September 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "When is a nation not a nation? Somaliland's dream of independence". The Guardian. 20 July 2018. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Mosalski, Ruth (26 March 2015). "Cardiff becomes only second UK council to recognise the Republic of Somaliland". Wales Online. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ "Somaliland Hails British Step Forward in Independence Bid". Voice of America. 5 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 February 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Galipo, Adele (8 November 2018). Return Migration and Nation Building in Africa: Reframing the Somali Diaspora. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-95713-0. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Liberatore, Giulia (29 June 2017). Somali, Muslim, British: Striving in Securitized Britain. Taylor & Francis. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-350-02773-2. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 3 February 2024.

- ^ Berns MacGown, Rima (1999). Muslims in the diaspora: the Somali communities of London and Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8020-8281-7.

- ^ Abdi, Mohameddeq Ali (19 April 2022). Why Somalia does not get the right direction. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 25. ISBN 978-3-7543-5218-2.

- ^ Ahmed, Ali J., ed. (1995). The invention of Somalia (1. print ed.). Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-932415-99-8.

- ^ "The great Somali migrations". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-56902-103-3.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 9780852552803.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1959). "The Galla in Northern Somaliland". Rassegna di Studi Etiopici. 15. Istituto per l'Oriente C. A. Nallino: 21–38. JSTOR 41299539. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Morin, Didier (2004). Dictionnaire historique afar: 1288–1982 [Historic dictionary of Afar: 1288–1982] (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782845864924. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ Ylönen, Aleksi Ylönen. The Horn Engaging the Gulf Economic Diplomacy and Statecraft in Regional Relations. p. 113. ISBN 9780755635191.

- ^ Horn of Africa, Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.

- ^ Michigan State University. African Studies Center, Northeast African studies, Volumes 11–12, (Michigan State University Press: 1989), p.32.

- ^ The Journal of The anthropological institute of Great Britain and Ireland| Vol.21 p. 161

- ^ Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society: Official Publication of the Coryndon Memorial Museum Vol.17 p. 76

- ^ Sub-Saharan Africa Report, Issues 57–67. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1986. p. 34. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Taariikhda Beerta Suldaan Cabdilaahi ee Hargeysa | Somalidiasporanews.com". Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b Genealogies of the Somal. Eyre and Spottiswoode (London). 1896.

- ^ Guure (Aboor), Ibraahim-rashiid Cismaan. "Taariikhda Saldanada Reer Guuleed Ee Somaliland". Togdheer News Network. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Maxaad ka taqaana Saldanada Ugu Faca Weyn Beesha Isaaq oo Tirsata 300 sanno ku dhawaad?". 13 February 2021. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Hugh Chisholm (ed.), The encyclopædia britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 25, (At the University press: 1911), p.383.

- ^ Foreign Department-External-B, August 1899, N. 33-234, NAI, New Delhi, Inclosure 2 in No. 1. And inclosure 3 in No. 1.

- ^ Sun, Sand and Somals – Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner.By H. Rayne,

- ^ Correspondence respecting the Rising of Mullah Muhammed Abdullah in Somaliland, and consequent military operations,1899–1901.pp.4–5.

- ^ Official history of the operations in Somaliland, 1901–04 by Great Britain. War Office. General Staff Published 1907.p.56

- ^ Official History of the Operations in Somaliland, Volume 1. p. 41

- ^ Parliamentary Papers: 1850-1908, Volume 48. H.M. Stationery Office. 1901. p. 65.

- ^ Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780810866041. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ Geshekter, Charles L. (1993). Somali Maritime History and Regional Sub-Cultures: A Neglected Theme of the Somali Crisis. The European Association of Somali Studies & School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). pp. 21–22.

- ^ "Piece of Berbera History: Reer Ahmed Nuh Ismail". wordpress.com. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 238.

- ^ Lewis, I.M. (1965). The Modern History of Somaliland: from Nation to State. Praeger. p. 35.

- ^ Pankhurst, R. (1965). Journal of Ethiopian Studies Vol. 3, No. 1. Institute of Ethiopian Studies. p. 45.

- ^ Hunt, Freeman (1856). The Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review, Volume 34. p. 694.

- ^ The Colonial Magazine and Commercial-maritime Journal, Volume 2. 1840. p. 22.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1965). "The Trade of the Gulf of Aden Ports of Africa in the Early Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 3 (1): 36–81. JSTOR 41965718. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Great Britain, House of Commons (1905). Sessional papers Inventory control record 1, Volume 92. HM Stationery Office. p. 385.

- ^ Ethnographie Nordost-Afrikas: Die Materielle Cultur Der Danakil, Galla Und Somal, 1893

- ^ a b Britain), Royal Geographical Society (Great (1893). Supplementary Papers. J. Murray.

- ^ The Geographical Journal. Royal Geographical Society. 1898.

- ^ a b c Geshekter, C. L. (1993). Somali Maritime History and Regional Sub-cultures: A Neglected Theme of the Somali Crisis. AAMH. p. 3. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Maren, Michael (2009). The road to hell: the ravaging effects of foreign aid and international charity. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-1439188415.

- ^ Regulating the Livestock Economy of Somaliland. Academy for Peace and Development. 2002. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ War-torn Societies Project; WSP Transition Programme (2005). Rebuilding Somaliland: Issues and Possibilities. Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-228-3. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ A Self-portrait of Somaliland: Rebuilding from the Ruins. Somaliland Centre for Peace and Development. 1999. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ de Waal, Alex. "CLASS AND POWER IN A STATELESS SOMALIA". ResearchGate. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Somalia: A Government at War with Its Own People (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 1990. p. 213. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783825830847. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p. 157.

- ^ Burton. F., Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa. p. 18.

- ^ Worldbank, Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, January 2005, Appendix 2, Lineage Charts, p. 55 Figure A-1

- ^ Country Information and Policy Unit, Home Office, Great Britain, Somalia Assessment 2001, Annex B: Somali Clan Structure Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, p. 43

- ^ a b c d e Dr. Ahmed Yusuf Farah, Matt Bryden. "Case Study of a Grassroots Peace Making Initiative". www.africa.upenn.edu. UNDP Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Kluijver, Robert. "The State in Somaliland". Sciences Po Paris. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2022 – via 16.

- ^ Mohamed Yusuf Hassan, Roberto Balducci, ed. (1993). Somalia: le radici del futuro. Il passaggio. p. 33. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Mogadishu memoir

- ^ Survey of China Mainland Press

- ^ Middleton, John (October 1965). "The Oxford Library of African Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964. A Selection of African Prose. I. Traditional Oral Texts; II. Written Prose. Compiled by W. H. Whiteley. Pp. xv, 200; viii, 185. 21s. each. - The Oxford Library of African Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964. Somali Poetry: an Introduction. By B. W. Andrzejewski and I. M. Lewis. Pp. viii, 167. 30s. - The Oxford Library of African Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964. The Heroic Recitations of the Bahima of Ankole. By H. F. Morris. Pp. xii, 142. 30s". Africa. 35 (4): 441–443. doi:10.2307/1157666. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1157666.

- ^ Bollettino della Società geografica italiana. ... 1893 (ser.3, vol. 5). p.372

- ^ Bollettino della Società geografica italiana By Società geografica italiana. 1893.

- ^ Somalia e Benadir: viaggio di esplorazione nell'Africa orientale. Prima traversata della Somalia, compiuta per incarico della Societá geografica italiana. Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti. 1899. The Somalis in general have a great inclination to poetry; a particular passion for the stories, the stories and songs of love.

- ^ "Somalia: Education in Transition". Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Board of directors". Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "BREAKING: Ibrahim Dheere Tycoon passes away in Djibouti | SomalilandInformer". www.somalilandinformer.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Somali Entrepreneurs". Salaan Media. 15 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Woldemariam, Michael (15 February 2018). Insurgent fragmentation in the Horn of Africa : rebellion and its discontents. Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-108-42325-0. OCLC 1000445166. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Mo Farah's family cheers him on from Somaliland village". The Guardian. 10 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Ahmed Said Ahmed" (in Finnish). Football Association of Finland. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

Kansallisuus: Suomi

- ^ "#80 Said Ahmed, Ahmed" (in Finnish). Veikkausliiga. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

Kansalaisuus FI

- ^ "Somaliland: Prominent Somali Journalist, Ahmed Hasan Awke Passes Away in Jigjiga | SomalilandInformer". www.somalilandinformer.com. Archived from the original on 16 February 2018.

- ^ "Afar arrimood ka ogow marxuum majaajileyste Sooraan". BBC News Somali (in Somali). Archived from the original on 31 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2021.