Jiayu Pass

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2007) |

Jiayu Pass or (simplified Chinese: 嘉峪关; traditional Chinese: 嘉峪關; pinyin: Jiāyù Guān) is the first frontier fortress at the west end of the Ming dynasty Great Wall, near the city of Jiayuguan in Gansu province. Along with Juyong Pass and Shanhai Pass, it is one of the main passes of the Great Wall. In the Ming period, foreign merchants and envoys from the Central Asia and West Asia mostly entered China through Jiayu Pass.[1]

Location

[edit]The pass is located at the narrowest point of the western section of the Hexi Corridor, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) southwest of the city of Jiayuguan in Gansu. The structure lies between two hills, one of which dominates Jiayuguan Pass. The fortress was built near an oasis that was then on the extreme western edge of China.

Description

[edit]

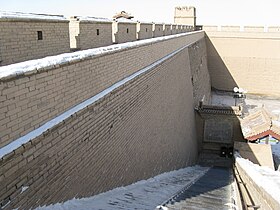

The fort is trapezoid-shaped with a perimeter of 733 metres (2,405 ft) and an area of more than 33,500 square metres (361,000 sq ft). The length of the wall is 733 metres (2,405 ft) and the height is 11 metres (36 ft).

There are two gates: one on the east side of the pass and the other on the west side. On each gate there is a building. An inscription of "Jiayuguan" in Chinese is written on a tablet at the building at the west gate. The south and north sides of the pass are connected to the Great Wall. There is a turret on each corner of the pass. On the north side, inside the two gates, there are wide roads leading to the top of the pass.

Jiayuguan consisted of three defense lines: an inner fort, an outer fort, and a moat.

When famous traveler Mildred Cable first visited Jiayuguan in 1923, she described it as

To the north of the central arch was a turreted watch-tower, and from it the long line of the wall dipped into a valley, climbed a hill and vanished over its summit. Then a few poplar trees came in sight, and it was evident from the shade of green at the foot of the wall that here was grass and water. Farther on a patch of wild irises spread a carpet of blue by the roadside, just where the cart passed under an ornamental memorial arch and lurched across a rickety bridge over a bubbling stream.[2]

Legends

[edit]

A fabulous legend recounts the meticulous planning involved in the construction of the pass. According to legend, when Jiayuguan was being planned, the official in charge asked the designer to estimate the exact number of bricks required and the designer gave him a number (99,999). The official questioned his judgment, asking him if that would be enough, so the designer added one brick. When Jiayuguan was finished, there was one brick left over, which was placed loose on one of the gates where it remains today.[3]

History

[edit]The structure was built during the early Ming dynasty, sometime around the year 1372. The fortress there was greatly strengthened due to fear of an invasion by Timur, but Timur died of old age while leading an army toward China.[4]

Significance

[edit]

Among the passes on the Great Wall, Jiayuguan is the most intact surviving ancient military building. The pass is also known by the name the "First and Greatest Pass Under Heaven" (天下第一雄關), which is not to be confused with the "First Pass Under Heaven" (天下第一關), a name for Shanhaiguan at the east end of the Great Wall near Qinhuangdao, Hebei.

The pass was a key waypoint of the ancient Silk Road.

Jiayuguan has a somewhat fearsome reputation because Chinese people who were banished were ordered to leave through Jiayuguan for the west, the vast majority never to return. Mildred Cable noted in her memoirs[5] that it was

known to men of a former generation as Kweimenkwan (Gate of the Demons)....The most important door was on the farther side of the fortress, and it might be called Traveller's Gate, though some spoke of it as the Gate of Sighs. It was a deep archway tunnelled in the thickness of the wall.... Every traveller toward the north-west passed through this gate, and it opened out on that great and always mysterious waste called the Desert of Gobi. The long archway was covered with writings...the work of men of scholarship, who had fallen on an hour of deep distress. Who were then the writers of this Anthology of Grief? Some were heavy-hearted exiles, others were disgraced officials, and some were criminals no longer tolerated within China's borders. Torn from all they loved on earth and banished with dishonoured name to the dreary regions outside.

Amongst those once banished in disgrace was the famous Chinese Opium War Viceroy of Liangguang, Commissioner Lin Zexu. A statue in his honor can today be found in a local park in Ürümqi.

More famous in Jiayuguan are the thousands of tombs from the Wei and Western Jin dynasty (266–420) discovered east of the city in recent years. The 700 excavated tombs are famous in China, and replicas or photographs of them can be seen in nearly every major Chinese museum. The bricks deserve their fame; they are both fascinating and charming, depicting such domestic scenes as preparing for a feast, roasting meat, picking mulberries, feeding chickens, and herding horses. Of the 18 tombs that have been excavated, only one is currently open to tourists. Many frescos have also been found around Jiayuguan but most are not open to visitors.

Photos

[edit]

|

References

[edit]- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (2021-10-11). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ^ Mildred Cable. The Gobi Desert. UK: Readers Union Ltd., 1950 (1st edition London 1942), pp. 13–14.

- ^ "The Great Wall in Gansu". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (30 January 2007). The Great Wall of China 221 BC–1644 AD. Osprey Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84603-004-8. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- ^ Cable, pp. 15–16

External links

[edit]- Complete Tour of JiaYuGuan Fortress Scenic Spot

- Complete Map of JiaYuGuan Fortress Scenic Spot

- A modern traveller's description of a recent visit can be found in PASSAGE, a publication of the Singapore Asian Civilisations Museum [1]