Ipse dixit

Ipse dixit (Latin for "he said it himself") is an assertion without proof, or a dogmatic expression of opinion.[1][2]

The fallacy of defending a proposition by baldly asserting that it is "just how it is" distorts the argument by opting out of it entirely: the claimant declares an issue to be intrinsic and immutable.[3]

History

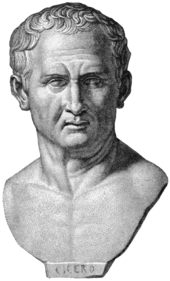

[edit]The Latin form of the expression comes from the Roman orator and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC) in his theological studies De Natura Deorum (On the Nature of the Gods) and is his translation of the Greek expression (with the identical meaning) autòs épha (αὐτὸς ἔφα), an argument from authority made by the disciples of Pythagoras when appealing to the pronouncements of the master rather than to reason or evidence.[4]

Before the early 17th century, scholars applied the ipse dixit term to justify their subject-matter arguments if the arguments previously had been used by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC).[5]

Ipse-dixitism

[edit]In the late 18th century, Jeremy Bentham adapted the term ipse dixit into the word ipse-dixitism.[6] Bentham coined the term to apply to all non-utilitarian political arguments.[7]

Legal usage

[edit]In modern legal and administrative decisions, the term ipse dixit has generally been used as a criticism of arguments based solely upon the authority of an individual or organization. For example, in National Tire Dealers & Retreaders Association, Inc. v. Brinegar, 491 F.2d 31, 40 (D.C. Cir. 1974), Circuit Judge Wilkey considered that the Secretary of Transportation's "statement of the reasons for his conclusion that the requirements are practicable is not so inherently plausible that the court can accept it on the agency's mere ipse dixit".[8]

In 1997, the Supreme Court of the United States recognized the problem of "opinion evidence which is connected to existing data only by the ipse dixit of an expert".[9] Likewise, the Supreme Court of Texas has held "a claim will not stand or fall on the mere ipse dixit of a credentialed witness".[10] "[W]hen you come across an argument that you recall the majority took issue with," U.S. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan advised readers of her dissent in 2023's Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, "go back to its response and ask yourself about the ratio of reasoning to ipse dixit."[11]

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln said in his speech at Freeport, Illinois, at the second joint debate with Stephen A. Douglas:[12]

I pass one or two points I have because my time will very soon expire, but I must be allowed to say that Judge Douglas recurs again, as he did upon one or two other occasions, to the enormity of Lincoln,—an insignificant individual like Lincoln,— upon his ipse dixit charging a conspiracy upon a large number of members of Congress, the Supreme Court, and two Presidents, to nationalize slavery. I want to say that, in the first place, I have made no charge of any sort upon my ipse dixit. I have only arrayed the evidence tending to prove it, and presented it to the understanding of others, saying what I think it proves, but giving you the means of judging whether it proves it or not. This is precisely what I have done. I have not placed it upon my ipse dixit at all.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Whitney, William Dwight (1906). "Ipse dixit". The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia. Vol. 4. Century. pp. 379–380.

- ^ Westbrook, Robert B. (1991). John Dewey and American Democracy. Cornell University Press. p. 359.

- ^ VanderMey, Randall; Meyer, Verne; Van Rys, John; Sebranek, Patrick (2012). COMP. Cengage. p. 183. "Bare assertion. The most basic way to distort an issue is to deny that it exists. This fallacy claims, 'That's just how it is.'"

- ^ Poliziano, Angelo. (2010). Angelo Poliziano's Lamia: Text, Translation, and Introductory Studies, p. 26; excerpt, "In Cicero's De natura deorum, as well as in other sources, the phrase “Ipse dixit” pointed to the notion that Pythagoras's disciples would use that short phrase as justification for adopting a position: if the master had said it, it was enough for them and there was no need to argue further."

- ^ Burton, George Ward. (1909). Burton's book on California and its sunlit skies of glory, p. 27; excerpt, "But by the time of Bacon, students had fallen into the habit of accepting Aristotle as an infallible guide, and when a dispute arose the appeal was not to fact, but to Aristotle's theory, and the phrase, Ipse dixit, ended all dispute."

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy. (1834). Deontology; or, The science of morality, Vol. 1, p. 323; excerpt, "ipsedixitism ... comes down to us from an antique and high authority, —-it is the principle recognised (so Cicero informs us) by the disciples of Pythagoras. Ipse {he, the master, Pythagoras), ipse dixit, — he has said it; the master has said that it is so; therefore, say the disciples of the illustrious sage, therefore so it is."

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy. (1838). Works of Jeremy Bentham, p. 192; excerpt, "... it is not a mere ipse dixit that will warrant us to give credit for utility to institutions, in which not the least trace of utility is discernible."

- ^ "National Tire Dealers & Retread. Ass'n Inc. vs. Brinegar". Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ Filan, citing General Electric Co. v. Joiner, 522 U.S. 136, 137; 118 S.Ct. 512; 139 L.Ed.2d 508 (1997).

- ^ Burrow v. Arce, 997 S.W.2d 229, 235 (Tex. 1999).

- ^ Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 598 U.S. ___ (2023), slip op. 4n2; Kagan, J., dissenting

- ^ From The complete works of Abraham Lincoln, Vol. III, pp. 290–291.

External links

[edit]- Bulfinch, Thomas (1913). "XXXIV. a. Pythagoras". Bartleby.com. Age of Fable: Vols. I & II: Stories of Gods and Heroes.

Ipse dixit

- Brewer, E. Cobham (1898). "Ipse dixit". Bartleby. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.

- "Ipse dixit". Bartleby. American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000. Archived from the original on Mar 22, 2006.