Line of Control

34°56′N 76°46′E / 34.933°N 76.767°E

| Line of Control | |

|---|---|

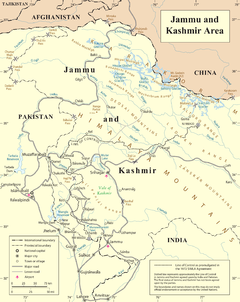

Political map of the Kashmir region showing the Line of Control (LoC) | |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 740 km (460 mi)[1] to 776 km (482 mi)[2][a] |

| History | |

| Established | 2 July 1972 Resulting from the ceasefire of 17 December 1971 and after ratification of the Shimla Treaty |

| Treaties | Simla Agreement |

The Line of Control (LoC) is a military control line between the Indian- and Pakistani-controlled parts of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir—a line which does not constitute a legally recognized international boundary, but serves as the de facto border. It was established as part of the Simla Agreement at the end of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Both nations agreed to rename the ceasefire line as the "Line of Control" and pledged to respect it without prejudice to their respective positions.[4] Apart from minor details, the line is roughly the same as the original 1949 cease-fire line.

The part of the former princely state under Indian control is divided into the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. The Pakistani-controlled section is divided into Azad Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan. The northernmost point of the Line of Control is known as NJ9842, beyond which lies the Siachen Glacier, which became a bone of contention in 1984. To the south of the Line of Control, (Sangam, Chenab River, Akhnoor), lies the border between Pakistani Punjab and the Jammu province, which has an ambiguous status: India regards it as an "international boundary", and Pakistan calls it a "working border".[5]

Another ceasefire line separates the Indian-controlled state of Jammu and Kashmir from the Chinese-controlled area known as Aksai Chin. Lying further to the east, it is known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC).[6]

Background

After the partition of India, present-day India and Pakistan contested the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir – India because of the ruler's accession to the country, and Pakistan by virtue of the state's Muslim-majority population. The First Kashmir War in 1947 lasted more than a year until a ceasefire was arranged through UN mediation. Both sides agreed on a ceasefire line.[7]

After another Kashmir War in 1965, and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 (which saw Bangladesh become independent), only minor modifications had been effected in the original ceasefire line. In the ensuing Simla Agreement in 1972, both countries agreed to convert the ceasefire line into a "Line of Control" (LoC) and observe it as a de facto border that armed action should not violate. The agreement declared that "neither side shall seek to alter it unilaterally, irrespective of mutual differences and legal interpretations".[8][9] The United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) had the role of investigating ceasefire violations (CFVs), however their role decreased after 1971.[10] In 2000, US President Bill Clinton referred to the Indian subcontinent and the Kashmir Line of Control, in particular, as one of the most dangerous places in the world.[11][12]

Characteristics

Terrain

The LoC from Kargil to Gurez comprises mountain passes and valleys with small streams and rivers.[13] The area up to around 14,000 feet (4,300 m) is wooded while the peaks rise higher.[13] Winter is snowy while summers are mild. From Gurez to Akhnoor, the area is mountainous and hilly respectively and is generally forested. There are tracks and minor roads connecting settlements.[13] The mix of flora and elevation affects visibility and line of sight significantly.[14]

Ceasefire violations

In 2018, two corps and a number of battalions of the Border Security Force manned the Indian side of the LoC.[15] The Rawalpindi Corps manned the Pakistani side.[15] Ceasefire violations (CFV's) are initiated and committed by both sides and show a symmetry.[16][17] The response to a CFV at one location can lead to shooting at an entirely different area.[18] Weapons used on the LoC include small arms, rocket-propelled grenades, recoilless rifles, mortars, automatic grenade launchers, rocket launchers and a number of other direct and indirect weaponry.[19] Military personnel on both sides risk being shot by snipers in moving vehicles, through bunker peepholes and during meals.[20]

The civilian population at the LoC, at some points ahead of the forward most post, has complicated the situation.[21] Shelling and firing by both sides along the LoC has resulted in civilian deaths.[22][23] Bunkers have been constructed for these civilian populations for protection during periods of CFV's.[24] India and Pakistan usually report only casualties on their own sides of the LoC,[25] with the media blaming the other side for the firing and each side claiming an adequate retaliation.[26]

According to Happymon Jacob, the reasons for CFVs along the LoC include[27] operational reasons (defence construction like observation facilities, the rule of the gun, lack of bilateral mechanisms for border management, personality traits and the emotional state of soldiers and commanders),[28] politico-strategic reasons,[29] proportional response (land grab, sniping triggered, "I am better than you", revenge firing),[30] accidental CFVs (civilian related, lack of clarity where the line is)[31] and other reasons (like testing the new boys, honour, prestige and humiliation, fun, gamesmanship).[32] Jacob ranks operational reasons as the main cause for CFVs, followed by retributive and politico-strategic reasons .[27]

Landmines and IEDs

Mines have been laid across the India–Pakistan border and the LoC in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 2001.[33] The small stretch of land between the rows of fencing is mined with thousands of landmines.[34] During the 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff thousands of acres of land along the LoC were mined.[35] Both civilians and military personnel on both sides have died in mine and improvised explosive device (IED)-related blasts, and many more have been injured.[35] Between January 2000 to April 2002, 138 military personnel were killed on the Indian side.[35]

Posts and bunkers

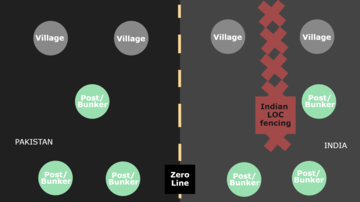

Reinforced sandbagged and concrete posts and bunkers are among the first line of defence along the LoC.[36][37] Armed soldiers man these positions with enough supplies for at least a week.[38] The posts and bunkers allow soldiers to sleep, cook, and keep a watch on enemy positions round the clock.[38] Some posts are located in remote locations. Animals are sometimes used to help transport loads, and at some posts animals are reared.[38] The living quarters and the forward facing bunker are located at some distance apart.[39] The locations of some posts do not follow any pre-ordained plan, rather they are in locations used during the First Kashmir War and the following cease-fire line, with minor adjustments made in 1972.[40]

Indian LoC fencing

India constructed a 550-kilometre (340 mi) barrier along the 740 kilometres (460 mi)[1]–776 kilometres (482 mi)[2] LoC by 2004.[41][42] The fence generally remains about 150 yards (140 m) on the Indian-controlled side. Its stated purpose is to exclude arms smuggling and infiltration by Pakistani-based separatist militants. The barrier, referred to as an Anti-Infiltration Obstacle System (AIOS), consists of double-row of fencing and concertina wire 8–12 feet (2.4–3.7 m) in height, and is electrified and connected to a network of motion sensors, thermal imaging devices, lighting systems and alarms. They act as "fast alert signals" for the Indian troops, who can be alerted and ambush the infiltrators trying to sneak in.[43][44]

The barrier's construction began in the 1990s but slowed in the early 2000s as hostilities between India and Pakistan increased. After a November 2003 ceasefire agreement, building resumed and was completed in late 2004. LoC fencing was completed in the Kashmir Valley and Jammu region on 30 September 2004.[42] According to Indian military sources, the fence has reduced the numbers of militants who routinely cross into the Indian side of the disputed region by 80%.[45] In 2017, a proposal for an upgraded smart fence on the Indian side was accepted.[44]

Border villages

A number of villages lie between the Indian fence and the zero line. Pakistan has not constructed a border fence, however a number of villages lie near the zero line.[46] In the Tithwal area, 13 villages are in front of the Indian fence.[46] The total number between the fence and zero line on the Indian side is estimated to be 60 villages and at least one million people are spread over the districts adjacent to the LoC from Rajouri to Bandipora.[47]

Infiltration and military cross-LoC movement

According to the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs, 1,504 "terrorists" attempted to infiltrate India in 2002.[48] Infiltration was one of India's main issues during the 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff.[49] There has been a decrease in infiltration over the years. Only a select number of individuals are successful; in 2016, the Ministry reported 105 successful infiltrations.[48] The Indian LoC fence has been constructed with a defensive mindset to counter infiltration.[50] The reduction in infiltration also points to a reduction in support of such activities within Pakistan.[51] During the 2019 Balakot airstrike, Indian planes crossed the LoC for the first time in 48 years.[52]

Crossing points

Pakistan and India officially designated five crossing points following the 2005 Kashmir earthquake—Nauseri-Tithwal; Chakoti-Uri; Hajipur-Uri; Rawalakot-Poonch and Tattapani-Mendhar.[53][54][55]

According to Azad Jammu and the Kashmir Cross LoC Travel and Trade Authority Act, 2016, the following crossing points are listed:[56][57]

- Rawalakot–Poonch

- Chakothi–Uri

- Chaliana–Tithwal

- Tatta Pani–Mendher

- Haji Peer–Silli Kot

Trade points include: Chakothi – Salamabad and Rawalakot (Titrinote) – Poonch (Chakkan-da-Bagh). The ordinance passed in 2011.[58][59]

Between 2005 and 2017, and according to Travel and Trade Authority figures, Muzaffarabad, Indian Kashmiris crossing over into Pakistan was about 14,000, while about 22,000 have crossed over to the Indian side.[60] Crossing legally for civilians is not easy. A number of documents are required and verified by both countries, including proof of family on the other side.[61] Even a short-term, temporary crossing invites interrogation by government agencies.[61] The Indian and Pakistani military use these crossing points for flag meetings and to exchange sweets during special occasions and festivals.[62][63][64] On 21 October 2008, for the first time in 61 years, cross-LoC trade was conducted between the two sides.[65] Trade across the LoC is barter trade.[66][67] In ten years, trade worth nearly PKR 11,446 crore or ₹5,000 crore (equivalent to ₹67 billion or US$770 million in 2023) has passed through the Chakothi – Salamabad crossing.[68]

Chilliana – Teetwal

The Teetwal crossing is across the Neelum River between Muzaffarabad and Kupwara. It is usually open only during the summer months,[69] and unlike the other two crossings is open only for the movement of people, not for trade.[57] The Tithwal bridge, first built in 1931, has been rebuilt twice.[70]

Chakothi – Salamabad

The Salamabad crossing point, or the Kamran Post, is on the road between Chakothi and Uri in the Baramulla district of Jammu and Kashmir along the LoC.[71][72] It is a major route for cross LoC trade and travel. Banking facilities and a trade facilitation centre are being planned on the Indian side.[73] The English name for the bridge in Uri translates as "bridge of peace". The Indian Army rebuilt it after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake when a mountain on the Pakistani side caved in.[74] This route was opened for trade in 2008 after being closed for 61 years.[75] The Srinagar–Muzaffarabad Bus crosses this bridge on the LoC.[76]

Tetrinote – Chakan Da Bagh

A road connects Kotli and Tatrinote on the Pakistan side of the LoC to the Indian Poonch district of Jammu and Kashmir through the Chakan Da Bagh crossing point.[72][77] It is a major route for cross LoC trade and travel. Banking facilities and a trade facilitation centre are being planned on the Indian side for the benefit of traders.[73]

Most of the flag meetings between Indian and Pakistani security forces are held here.[78]

Tattapani – Mendhar

The fourth border crossing between Tattapani and Mendhar was opened on 14 November 2005.[79]

Impact on civilians

The Line of Control divided the Kashmir into two and closed the Jhelum valley route, the only way in and out of the Kashmir Valley from Pakistani Punjab. This ongoing territorial division severed many villages and separated family members.[80][81] Some families could see each other along the LoC in locations such as the Neelum River, but were unable to meet.[82] In certain locations, women on the Pakistan side on the LoC have been instrumental in influencing infiltration and ceasefire violations; they have approached nearby Pakistani Army camps directly and insisted infiltration stop, which reduces India's cross LoC firing.[83]

In popular culture

Documentaries covering the LoC and related events include A journey through River Vitasta,[84] Raja Shabir Khan's Line of Control[85] and HistoryTV18's Kargil: Valour & Victory.[86] A number of Bollywood films on the 1999 Kargil conflict have involved depictions and scenes of the line of control including LOC: Kargil (2003),[87] Lakshya (2004)[88] and Gunjan Saxena: The Kargil Girl (2020).[89] Other Bollywood films include Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019)[90] and Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015),[91] and streaming television shows such as Avrodh (2020).[92]

See also

- India–Pakistan relations

- Transport between India and Pakistan

- Actual Ground Position Line – the line of separation near the Siachen Glacier

- United Nations Military Observer Group in Kashmir

References

- Notes

- ^ 767 kilometres (477 mi) long according to Mahmud Ali Durrani (2001)[3]

- Citations

- ^ a b "Clarifications on LoC". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. 2 July 1972. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

...thus clearly delineating the entire stretch of Line of Control running through 740 Km starting from Sangam and ending at Pt NJ-9842.

- ^ a b Arora & Kumar 2016, p. 6.

- ^ Durrani 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Wirsing 1998, p. 13: 'With particular reference to Kashmir, they agreed that: ... in J&K, the Line of Control resulting from the ceasefire of 17 December 1971, shall be respected by both sides without prejudice to the recognised position of either side.'

- ^ Wirsing 1998, p. 10.

- ^ Wirsing 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Wirsing 1998, pp. 4–7.

- ^ Wirsing 1998, p. 13.

- ^ "Simla Agreement". Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. 2 July 1972. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 110–111.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (23 March 2000). "Analysis: The world's most dangerous place?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ Krishnaswami, Sridhar (11 March 2000). "'Most dangerous place'". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Durrani 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Durrani 2001, p. 39.

- ^ a b Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 109.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 145.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 86.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 85.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 18.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 82.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 113.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 96, 100.

- ^ Siddiqui, Naveed (25 December 2017). "3 Pakistani soldiers martyred in 'unprovoked' cross-LoC firing by Indian army: ISPR". DAWN. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "J&K completes 84% of underground bunkers along LoC to protect residents during border shelling". ThePrint. PTI. 7 February 2021. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Zakaria 2018, p. xxiv-xxv.

- ^ Zakaria 2018, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 158–180.

- ^ Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 181–187.

- ^ Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 187–202.

- ^ Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 207–212.

- ^ Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 202–207.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 97.

- ^ Umar, Baba (30 April 2011). "Mines of war maim innocents". Tehelka. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 98.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 148.

- ^ AP (3 April 2021). "Pakistan-India peace move silences deadly LoC". Dawn.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 148–149.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 150.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 151.

- ^ Williams, Matthias (20 October 2008). Scrutton, Alistair (ed.). "FactBox – Line of control between India and Pakistan". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ a b "LoC fencing completed: Mukherjee". The Times of India. 16 December 2004. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.

- ^ Kumar, Vinay (1 February 2004). "LoC fencing in Jammu nearing completion". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 16 February 2004. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b Peri, Dinakar (30 April 2017). "Army set to install smart fence along LoC". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Gilani, Iftikhar (4 March 2005). "Harsh weather likely to damage LoC fencing". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- ^ a b Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 155.

- ^ Sharma, Ashutosh (1 April 2021). "Caught in the twilight zone between India and Pakistan, border villages struggle to survive". The Caravan. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ a b Jacob, Line on Fire 2018, pp. 156–157.

- ^ "British and US surveillance may monitor Kashmir". The Guardian. 12 June 2002. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Katoch, Dhruv C (Winter 2013). "Combatting Cross-Border Terrorism: Need for a Doctrinal Approach" (PDF). CLAWS Journal: 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Khan, Aarish Ullah (September 2005). "The Terrorist Threat and the Policy Response in Pakistan" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. p. 35. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021. SIPRI Policy Paper No. 11

- ^ Gokhale, Nitin A. (2019). "1. Pulwama: Testing Modi's Resolve". Securing India the Modi Way: Balakot, Anti Satellite Missile Test and More. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-93-89449-27-3. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan, India agree to open five LoC points". DAWN. 30 October 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Hussain, Aijaz (21 November 2005). "Kashmir earthquake: Opening of relief points along LoC becomes high point of Indo-Pak ties". India Today. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "India, Pakistan to open military border". Al Jazeera. 30 October 2005. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Azad Jammu and Kashmir Cross LoC Travel and Trade Authority Act, 2016 Archived 26 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Act XVI of 2016. Law, Justice, Parliamentary Affairs and Human Rights Department, AJK Government. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Crossing Points". ajktata.gok.pk (AJK Travel and Trade Authority). Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ "The Azad Jammu and Kashmir Cross LoC Travel and Trade Authority Ordinance, 2011 (AJK Ordinance No. XXXII of 2011)". Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2021 – via nasirlawsite.com.

- ^ Singh, Priyanka (1 January 2013). "Prospects of Travel and Trade across the India–Pakistan Line of Control (LoC)". International Studies. 50 (1–2): 71–91. doi:10.1177/0020881715605237. ISSN 0020-8817. S2CID 157985090.

- ^ Jacob, The Line of Control (2018), 114–115.

- ^ a b Zakaria 2018, p. 71.

- ^ "Indian, Pakistani troops exchange sweets along LoC in Kashmir on Pak's I-Day". Business Standard India. PTI. 14 August 2021. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "India, Pakistan forces exchange Eid sweets for first time since Pulwama". The Times of India. 22 June 2021. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Bhalla, Abhishek (26 March 2021). "India, Pakistan hold brigade commanders-level meet to discuss peace at LoC". India Today. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Hafeez 2014, p. 80.

- ^ Naseem, Ishfaq (11 January 2017). "Kashmir's Cross-Border Barter Trade". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Taneja, Nisha; Bimal, Samridhi (2015). "Revisiting India Pakistan Cross-LoC Trade". Economic and Political Weekly. 50 (6): 21–23. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 24481356.

Two key features form the core of the LOC trading arrangement: (i) barter exchange, and (ii) zero customs duty.

- ^ Ehsan, Mir (29 May 2018). "Border business: Where Kashmir unites India, Pakistan via trade". Hindustan Times. Salamadad (Uri). Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Iqbal, Mir (3 November 2016). "Teetwal LoC crossing point reopens after 3 months". Greater Kashmir. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Philip, Snehesh Alex (16 October 2020). "A shut LoC bridge, and a Kashmir village living under the shadow of Pakistani snipers". ThePrint. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Pakistan: Second border crossing-point opens to allow relief from India". ReliefWeb (Press release). 10 November 2005. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Jammu and Kashmir: Goods over Rs 3,432 crore traded via two LoC points in 3 years". The Economic Times. PTI. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Cross-LoC trade at Rs 2,800 crore in last three years". The Economic Times. PTI. 13 June 2016. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "J&K CM inaugurates rebuilt Aman Setu". Hindustan Times. IANS. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Ramasubbu, Krishnamurthy (21 October 2008). "Trucks start rolling, duty-free commerce across LoC opens". Livemint. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Re-erected Kaman Aman Setu will be inaugurated on Monday". Outlook. PTI. 19 February 2006. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Chakan-Da-Bagh in Poonch". Zee News. 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013.

- ^ "India, Pakistan hold flag meeting". The Hindu. 23 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Fourth Kashmir crossing opens". DAWN. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Ranjan Kumar Singh, Sarhad: Zero Mile, (Hindi), Parijat Prakashan, ISBN 81-903561-0-0

- ^ Closer to ourselves: stories from the journey towards peace in South Asia. WISCOMP, Foundation for Universal Responsibility of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. 2008. p. 75. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ^ Zakaria 2018, p. 84.

- ^ Zakaria 2018, pp. 107–109.

- ^ "Film-making beyond borders: The process is the message". Conciliation Resources. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Line of Control". DMZ International Documentary Film Festival. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "HistoryTV18 brings viewers true stories of courage and sacrifice in the Kargil War". Adgully.com. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Budha 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Dsouza, Vinod (17 August 2018). "Atal Bihari Vajpayee's Tenure As PM Inspired Hrithik Roshan's Lakshya & John Abraham's Parmanu". Filmibeat. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Gunjan Saxena: India female pilot's war biopic flies into a row". BBC News. 19 August 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Mishra, Nivedita (15 August 2019). "Independence Day 2019: How Uri The Surgical Strike changed the way Indian patriotic films are made". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Chakravarty, Ipsita (27 July 2015). "How Bajrangi Bhaijaan brought peace to the LoC and solved the Kashmir issue". Dawn. Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Ramnath, Nandini (31 July 2020). "'Avrodh' review: Show about 2016 surgical strike goes beyond Line of Control in more ways than one". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- Bibliography

- Wirsing, Robert G. (1998), "War or Peace on the Line of Control?", in Clive Schofield (ed.), Boundary and Territory Briefing, Volume 2, Number 5, ISBN 1-897643-31-4 (Page numbers cited per the e-document)

- Bharat, Meenakshi; Kumar, Nirmal, eds. (2012). Filming the Line of Control: The Indo–Pak Relationship through the Cinematic Lens. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-51606-1.

- — Budha, Kishore (2012), "1", Genre Development in the Age of Markets and Nationalism: The War Film

- Jacob, Happymon (2018). The Line of Control: Travelling with the Indian and Pakistani Armies. Penguin Random House India. ISBN 978-93-5305-352-9. (print version)

- — Jacob, Happymon (2018). Line on Fire: Ceasefire Violations and India–Pakistan Escalation Dynamics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-909547-6. (e-book version)

- Zakaria, Anam (2018). Between the Great Divide: A Journey into Pakistan-Administered Kashmir. India: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-93-5277-947-5.

- Hafeez, Mahwish (2014). "The Line of Control (LoC) Trade: A Ray of Hope". Strategic Studies. 34 (1). Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad: 74–93. ISSN 1029-0990. JSTOR 48527555.

- Arora, RK; Kumar, Manoj (November 2016), Comprehensive Integrated Border Management System: Implementation Challenges (PDF), Occasional Paper No. 100, Observer Research Foundation

- Durrani, Major General (Retd) Mahmud Ali (July 2001), Enhancing Security through a Cooperative Border Monitoring Experiment: A Proposal for India and Pakistan, Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energy, Cooperative Monitoring Center, Sandia National Laboratories, doi:10.2172/783991, OSTI 783991

Further reading

- Akhtar, Shaheen (2017). "Living on the frontlines: Perspective from Poonch and Kotli region of AJK" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. 24 (2).

- — Akhtar, Shaheen (2017). "Living on the Frontlines: Perspective from the Neelum Valley" (PDF). Margalla Papers. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2020.

- Bali, Pawan; Akhtar, Shaheen (31 July 2017), Kashmir Line of Control and Grassroots Peacebuilding (PDF), United States Institute of Peace

- Jacob, Happymon (2017), Ceasefire violations in Jammu and Kashmir (PDF), United States Institute of Peace, ISBN 978-1-60127-672-8

- Kira, Altaf Hussain (September 2011), Cross-LoC trade in Kashmir: From Line of Control to Line of Commerce (PDF), IGIDR, Mumbai

- —Kira, Altaf Hussain (2011). "From Line of Control to Line of Commerce". Economic and Political Weekly. 46 (40): 16–18. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 23047415.

- Padder, Sajad A. (2015). "Cross-Line of Control Trade: Problem and Prospects". Journal of South Asian Studies. 3 (1): 37–48.

- Ranjan Kumar Singh (2007), Sarhad: Zero Mile (in Hindi), Parijat Prakashan, ISBN 81-903561-0-0

- "Relevance of Simla Agreement". Editorial Series. Khan Study Group. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Reports

- Smart border management: An Indian perspective (PDF), FICCI, PwC India, September 2016

- Smart border management: Contributing to a US$5 trillion economy (PDF), FICCI, Ernst & Young India, 2019, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2021, retrieved 7 September 2021

- Photographs

- "LoC: Line of Control" (Photo Gallery). Outlook India. Retrieved on 3 September 2021.

- — Photos 1 to 100

- — Photos 101 to 176