Mars Orbiter Mission

Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft around Mars (illustration) | |||||||||||||

| Names | Mangalyaan-1 MOM | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Mars orbiter | ||||||||||||

| Operator | ISRO | ||||||||||||

| COSPAR ID | 2013-060A | ||||||||||||

| SATCAT no. | 39370 | ||||||||||||

| Website | isro.gov.in | ||||||||||||

| Mission duration | Planned: 6 months[1] Final: 7 years, 6 months, 8 days | ||||||||||||

| Spacecraft properties | |||||||||||||

| Bus | I-1K[2] | ||||||||||||

| Manufacturer | U R Rao Satellite Centre | ||||||||||||

| Launch mass | 1,337.2 kg (2,948 lb)[3] | ||||||||||||

| BOL mass | ≈550 kg (1,210 lb)[4] | ||||||||||||

| Dry mass | 482.5 kg (1,064 lb)[3] | ||||||||||||

| Payload mass | 13.4 kg (30 lb)[3] | ||||||||||||

| Dimensions | 1.5 m (4.9 ft) cube | ||||||||||||

| Power | 840 watts[2] | ||||||||||||

| Start of mission | |||||||||||||

| Launch date | 5 November 2013, 09:08 UTC[5][6] | ||||||||||||

| Rocket | PSLV-XL C25[7] | ||||||||||||

| Launch site | Satish Dhawan Space Centre, FLP | ||||||||||||

| Contractor | ISRO | ||||||||||||

| End of mission | |||||||||||||

| Last contact | April 2022[8] | ||||||||||||

| Mars orbiter | |||||||||||||

| Orbital insertion | 24 September 2014, 02:10 UTC (7:40 IST)[9][10] MSD 50027 06:27 AMT 3715 days / 3616 sols | ||||||||||||

| Orbital parameters | |||||||||||||

| Periareon altitude | 421.7 km (262.0 mi)[9] | ||||||||||||

| Apoareon altitude | 76,993.6 km (47,841.6 mi)[9] | ||||||||||||

| Inclination | 150.0°[9] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Insignia depicting journey from Earth to an elliptical Martian orbit using Mars symbol | |||||||||||||

Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), unofficially known as Mangalyaan[11] (Sanskrit: Maṅgala 'Mars', Yāna 'Craft, Vehicle'),[12][13] was a space probe orbiting Mars since 24 September 2014. It was launched on 5 November 2013 by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).[14][15][16][17] It was India's first interplanetary mission[18] and it made ISRO the fourth space agency to achieve Mars orbit, after Soviet space program, NASA, and the European Space Agency.[19] It made India the first Asian nation to reach Martian orbit and the second national space agency in the world to do so on its maiden attempt after the European Space Agency did in 2003.[20][21][22][23]

The Mars Orbiter Mission probe lifted off from the First Launch Pad at Satish Dhawan Space Centre (Sriharikota Range SHAR), Andhra Pradesh, using a Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) rocket C25 at 09:08 (UTC) on 5 November 2013.[5][24] The launch window was approximately 20 days long and started on 28 October 2013.[6] The MOM probe spent about a month in Earth orbit, where it made a series of seven apogee-raising orbital manœuvres before trans-Mars injection on 30 November 2013 (UTC).[25] After a 298-day transit to Mars, it was put into Mars orbit on 24 September 2014.

The mission was a technology demonstrator project to develop the technologies for designing, planning, management, and operations of an interplanetary mission.[26] It carried five scientific instruments.[27] The spacecraft was monitored from the Spacecraft Control Centre at ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) in Bengaluru with support from the Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) antennae at Bengaluru, Karnataka.[28]

On 2 October 2022, it was reported that the orbiter had irrecoverably lost communications with Earth after entering a seven-hour eclipse period in April 2022 that it was not designed to survive.[29][30][31] The following day, ISRO released a statement that all attempts to revive MOM had failed and officially declared it dead.[32] The loss of fuel preventing the attitude adjustment of the spacecraft required to sustain battery power to the probe's instruments had been discussed at an ISRO conference on September 27 commemorating the spacecraft's eight-year anniversary of insertion into Mars orbit.[33]

History

[edit]In November 2008, the first public acknowledgement of an uncrewed mission to Mars was announced by then-ISRO chairman G. Madhavan Nair.[34] The MOM mission concept began with a feasibility study in 2010 by the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology after the launch of lunar satellite Chandrayaan-1 in 2008. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh approved the project on 3 August 2012,[35][36] after the Indian Space Research Organisation completed ₹125 crore (US$15 million) of required studies for the orbiter.[37] The total project cost may be up to ₹454 crore (US$54 million).[14][38] The satellite costs ₹153 crore (US$18 million) and the rest of the budget has been attributed to ground stations and relay upgrades that will be used for other ISRO projects.[39]

The space agency had planned the launch on 28 October 2013 but was postponed to 5 November following the delay in ISRO's spacecraft tracking ships to take up pre-determined positions due to poor weather in the Pacific Ocean.[6] Launch opportunities for a fuel-saving Hohmann transfer orbit occur every 26 months, in this case the next two would be in 2016 and 2018.[40]

Assembly of the PSLV-XL launch vehicle, designated C25, started on 5 August 2013.[41] The mounting of the five scientific instruments was completed at Indian Space Research Organisation Satellite Centre, Bengaluru, and the finished spacecraft was shipped to Sriharikota on 2 October 2013 for integration to the PSLV-XL launch vehicle.[41] The satellite's development was fast-tracked and completed in a record 15 months,[42] partly due to using reconfigured Chandrayaan-2 orbiter bus.[43] Despite the US federal government shutdown, NASA reaffirmed on 5 October 2013 it would provide communications and navigation support to the mission "with their Deep Space Network facilities.".[44] During a meeting on 30 September 2014, NASA and ISRO officials signed an agreement to establish a pathway for future joint missions to explore Mars. One of the working group's objectives will be to explore potential coordinated observations and science analysis between the MAVEN orbiter and MOM, as well as other current and future Mars missions.[45]

On 2 October 2022, it was reported that the orbiter had irrecoverably lost communications with Earth after entering long eclipse period in April 2022 that it was not designed to survive. At the time of communications loss it was unknown whether the probe had lost power or inadvertently realigned its Earth-facing antenna during automatic maneuvers.[29]

Team

[edit]Some of the scientists of ISRO and engineers involved in the mission include:[46]

- K. Radhakrishnan led as Chairman ISRO.

- Mylswamy Annadurai was the Programme Director and was in charge of the overall project, budget management as well as direction for spacecraft configuration, schedule and resources.

- V Kesava Raju was the Mars Orbiter Mission Director.

- Subbiah Arunan was the Project Director at the Mars Orbiter Mission.

- BS Kiran was the Associate Project Director of Flight Dynamics.

- V Koteswara Rao was the ISRO scientific secretary.

- Chandradathan was the Director of the Liquid Propulsion System.

- Moumita Dutta was the Project manager of the Mars Orbiter Mission.

- Nandini Harinath was the Deputy Operations Director of Navigation.

- Ritu Karidhal was the Deputy Operations Director of Navigation.

- B Jayakumar was an Associate Project Director at the PSLV programme which was responsible for testing the rocket systems.

- S Ramakrishnan was the Director who helped in the development of the liquid propulsion system of the PSLV launcher.

- P. Kunhikrishnan was the Project Director in the PSLV programme. He was also a Mission director of the PSLV-C25/Mars Orbiter Mission.

- A. S. Kiran Kumar was the Director of the Satellite Application Centre, who later went on to be the Chairman ISRO after this, when the team studied the Mard

- M. Y. S. Prasad is the Director at Satish Dhawan Space Centre. He was also the chairman of the Launch Authorisation Board.

- MS Pannirselvam was the Chief General Manager at the Sriharikota Rocket port and was tasked to maintain launch schedules.

- S. K. Shivakumar was the Director at the ISRO Satellite Centre. He was also a Project Director for the Indian Deep Space Network. Mars Orbiter Mission is the product of ISRO Satellite Centre (ISAC). He spearheaded the task of conceptualization, design and realization of the unique spacecraft MOM. He ingeniously planned to realize the spacecraft in a record time of 15 months.

Cost

[edit]The total cost of the mission was approximately ₹450 Crore (US$73 million),[47][48] making it the least-expensive Mars mission to date.[49] The low cost of the mission was ascribed by ISRO chairman K. Radhakrishnan to various factors, including a "modular approach", few ground tests and long working days (18 to 20 hours) for scientists.[50] BBC's Jonathan Amos specified lower worker costs, home-grown technologies, simpler design, and a significantly less complicated payload than NASA's MAVEN.[27] Prime Minister Modi said that the mission cost less than the film Gravity.[51]

Mission objectives

[edit]The primary objective of the mission is to develop the technologies required for designing, planning, management and operations of an interplanetary mission.[26] The secondary objective is to explore Mars' surface features, morphology, mineralogy and Martian atmosphere using indigenous scientific instruments.[52]

The main objectives are to develop the technologies required for designing, planning, management and operations of an interplanetary mission comprising the following major tasks:[53]: 42

- Orbit manoeuvres to transfer the spacecraft from Earth-centred orbit to heliocentric trajectory and finally, capture into Martian orbit

- Development of force models and algorithms for orbit and attitude (orientation) computations and analysis

- Navigation in all phases

- Maintain the spacecraft in all phases of the mission

- Meeting power, communications, thermal and payload operation requirements

- Incorporate autonomous features to handle contingency situations

Scientific objectives

[edit]The scientific objectives deal with the following major aspects:[53]: 43

- Exploration of Mars surface features by studying the morphology, topography and mineralogy

- Study the constituents of Martian atmosphere including methane and CO2 using remote sensing techniques

- Study the dynamics of the upper atmosphere of Mars, effects of solar wind and radiation and the escape of volatiles to outer space

The mission would also provide multiple opportunities to observe the Martian moon Phobos and also offer an opportunity to identify and re-estimate the orbits of asteroids seen during the Martian Transfer Trajectory.[53]: 43 The spacecraft also provided the first views ever of the far side of Martian Moon Deimos.

Studies

[edit]In May–June 2015 Indian scientists got an opportunity to study the Solar Corona during the Mars conjunction when earth and Mars are on the opposite sides of the sun. During this period the S band waves emitted by MOM were transmitted through the Solar Corona that extends millions of kms into space. This event helped scientists study the Solar surface and regions where temperature changed abruptly.[54]

Spacecraft design

[edit]

- Mass: The lift-off mass was 1,337.2 kg (2,948 lb), including 852 kg (1,878 lb) of propellant.[3]

- Bus: The spacecraft's bus is a modified I-1 K structure and propulsion hardware configuration, similar to Chandrayaan-1, India's lunar orbiter that operated from 2008 to 2009, with specific improvements and upgrades needed for a Mars mission.[52] The satellite structure is constructed of an aluminium and composite fibre reinforced plastic (CFRP) sandwich construction.[55]

- Power: Electric power is generated by three solar array panels of 1.8 m × 1.4 m (5 ft 11 in × 4 ft 7 in) each (7.56 m2 (81.4 sq ft) total), for a maximum of 840 watts of power generation in Mars orbit. Electricity is stored in a 36 Ah Lithium-ion battery.[2][56]

- Propulsion: A liquid fuel engine with a thrust of 440 newtons (99 lbf) is used for orbit raising and insertion into Mars orbit. The orbiter also has eight 22-newton (4.9 lbf) thrusters for attitude control (orientation).[57] Its propellant mass at launch was 852 kg (1,878 lb).[2]

- Attitude and Orbit Control System: Maneuvering system that includes electronics with a MAR31750 processor, two star sensors, a solar panel Sun sensor, a coarse analog Sun sensor, four reaction wheels, and the primary propulsion system.[2][58]

- Antennae: Low gain antenna, mid gain antenna, and high gain antenna.[2]

Scientific instruments

[edit]

Note: The position of MENCA and LAP were later slightly shifted horizontally along the shown sides of their panels

The 15 kg (33 lb) scientific payload consists of five instruments:[59][60][61]

| Payload | Mass | Image | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric studies | |||

| Lyman-Alpha Photometer (LAP) | 1.97 kg (4.3 lb) | A photometer that measures the relative abundance of deuterium and hydrogen from Lyman-alpha emissions in the upper atmosphere. Measuring the deuterium/hydrogen ratio will allow an estimation of the amount of water loss to outer space. The nominal plan to operate LAP is between the ranges of approximately 3,000 km (1,900 mi) before and after Mars periapsis. Minimum observation duration for achieving LAP's science goals is 60 minutes per orbit during normal range of operation. The objectives of this instrument consists of stimation of D/H ratio, estimation of escape flux of H2 corona and generation of hydrogen & deuterium coronal profiles.[53]: 56, 57 | |

| Methane Sensor for Mars (MSM) | 2.94 kg (6.5 lb) |

|

It was meant to measure methane in the atmosphere of Mars, if any, and map its sources with an accuracy of few 10s parts-per-billion (ppb).[59] After entering Mars orbit it was determined that the instrument, although in good working condition, had a design flaw and it was incapable of distinguishing methane on Mars. The instrument can accurately map Mars albedo at 1.65 um.[62][63] MSM design flaw: The MSM sensor was expected to measure methane in the Mars atmosphere; methane on Earth is often associated with life. However, after it entered orbit, it was reported that there was an issue with how it collected and processed data. The spectrometer could measure intensity of different spectral bands, [such as methane] but instead of sending back the spectra, it sent back the sum of the sampled spectra and also the gaps between the sampled lines. The difference was supposed to be the methane signal, but since other spectra such as carbon dioxide could have varying intensities, it was not possible to determine the actual methane intensity. The device was repurposed as an albedo mapper.[64] |

| Surface imaging studies | |||

| Thermal Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (TIS) | 3.20 kg (7.1 lb) | TIS measures the thermal emission and can be operated during both day and night. It would map surface composition and mineralogy of Mars and also monitor atmospheric CO2 and turbidity (required for the correction of MSM data). Temperature and emissivity are the two basic physical parameters estimated from thermal emission measurement. Many minerals and soil types have characteristic spectra in TIR region. TIS can map surface composition and mineralogy of Mars.[53]: 59 | |

| Mars Colour Camera (MCC) | 1.27 kg (2.8 lb) |

|

This tricolour camera gives images and information about the surface features and composition of Martian surface. It is useful to monitor the dynamic events and weather of Mars like dust storms/atmospheric turbidity. MCC will also be used for probing the two satellites of Mars, Phobos and Deimos. MCC would provide context information for other science payloads. MCC images are to be acquired whenever MSM and TIS data is acquired. Seven Apoareion Imaging of the entire disc and multiple Periareion images of 540 km × 540 km (340 mi × 340 mi) are planned in every orbit.[53]: 58 |

| Particle environment studies | |||

| Mars Exospheric Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA) | 3.56 kg (7.8 lb) |

|

It is a quadrupole mass analyser capable of analysing the neutral composition of particles in the range of 1–300 amu (atomic mass unit) with unit mass resolution. The heritage of this payload is from Chandra's Altitudinal Composition Explorer (CHACE) payload aboard the Moon Impact Probe (MIP) in Chandrayaan-1 mission. MENCA is planned to perform five observations per orbit with one hour per observation.[53]: 58 |

Telemetry and command

[edit]The ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network performed navigation and tracking operations for the launch with ground stations at Sriharikota and Port Blair in India, Brunei and Biak in Indonesia,[65] and after the spacecraft's apogee became more than 100,000 km, an 18 m (59 ft) and a 32 m (105 ft) diameter antenna of the Indian Deep Space Network were utilised.[66] The 18 m (59 ft) dish antenna was used for communication with the craft until April 2014, after which the larger 32 m (105 ft) antenna was used.[67] NASA's Deep Space Network is providing position data through its three stations located in Canberra, Madrid and Goldstone on the US West Coast during the non-visible period of ISRO's network.[68] The South African National Space Agency's (SANSA) Hartebeesthoek (HBK) ground station is also providing satellite tracking, telemetry and command services.[69]

Communications

[edit]Communications are handled by two 230-watt TWTAs and two coherent transponders. The antenna array consists of a low-gain antenna, a medium-gain antenna and a high-gain antenna. The high-gain antenna system is based on a single 2.2-metre (7 ft 3 in) reflector illuminated by a feed at S-band. It is used to transmit and receive the telemetry, tracking, commanding and data to and from the Indian Deep Space Network.[2]

Mission profile

[edit]| Phase | Date | Event | Detail | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geocentric phase | 5 November 2013 09:08 UTC | Launch | Burn time: 15:35 min in 5 stages | Apogee: 23,550 km (14,630 mi) | [70] |

| 6 November 2013 19:47 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre | Burn time: 416 sec | Apogee: 28,825 km (17,911 mi) | [71] | |

| 7 November 2013 20:48 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre | Burn time: 570.6 sec | Apogee: 40,186 km (24,970 mi) | [72][73] | |

| 8 November 2013 20:40 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre | Burn time: 707 sec | Apogee: 71,636 km (44,513 mi) | [72][74] | |

| 10 November 2013 20:36 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre | Incomplete burn | Apogee: 78,276 km (48,638 mi) | [75] | |

| 11 November 2013 23:33 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre (supplementary) | Burn time: 303.8 sec | Apogee: 118,642 km (73,721 mi) | [72] | |

| 15 November 2013 19:57 UTC | Orbit raising manoeuvre | Burn time: 243.5 sec | Apogee: 192,874 km (119,846 mi) | [72][76] | |

| 30 November 2013 19:19 UTC | Trans-Mars injection | Burn time: 1328.89 sec | Heliocentric insertion | [77] | |

| Heliocentric phase | December 2013 – September 2014 | En route to Mars – The probe travelled a distance of 780,000,000 kilometres (480,000,000 mi) in a Hohmann transfer orbit[40] around the Sun to reach Mars.[67] This phase plan included up to four trajectory corrections if needed. | [78][79][80][81][82] | ||

| 11 December 2013 01:00 UTC | 1st Trajectory correction | Burn time: 40.5 sec | Success | [72][80][81][82] | |

| 9 April 2014 | 2nd Trajectory correction (planned) | Not required | Rescheduled for 11 June 2014 | [79][82][83][84][85] | |

| 11 June 2014 11:00 UTC | 2nd Trajectory correction | Burn time: 16 sec | Success | [83][86] | |

| August 2014 | 3rd Trajectory correction (planned) | Not required[83][87] | [79][82] | ||

| 22 September 2014 | 3rd Trajectory correction | Burn time: 4 sec | Success | [79][82][88] | |

| Areocentric phase | 24 September 2014 | Mars orbit insertion | Burn time: 1388.67 sec | Success | [9] |

Launch

[edit]

ISRO originally intended to launch MOM with its Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV),[89] but the GSLV failed twice in 2010 and still had issues with its cryogenic engine.[90] Waiting for the new batch of rockets would have delayed the MOM for at least three years,[91] so ISRO opted to switch to the less-powerful Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV). Since it was not powerful enough to place MOM on a direct-to-Mars trajectory, the spacecraft was launched into a highly elliptical Earth orbit and used its own thrusters over multiple perigee burns (to take advantage of the Oberth effect) to place itself on a trans-Mars trajectory.[89]

On 19 October 2013, ISRO chairman K. Radhakrishnan announced that the launch had to be postponed by a week for 5 November 2013 due to a delay of a crucial telemetry ship reaching Fiji. The launch was rescheduled.[6] ISRO's PSLV-XL placed the satellite into Earth orbit at 09:50 UTC on 5 November 2013,[37] with a perigee of 264.1 km (164.1 mi), an apogee of 23,903.6 km (14,853.0 mi), and inclination of 19.20 degrees,[70] with both the antenna and all three sections of the solar panel arrays deployed.[92] During the first three orbit raising operations, ISRO progressively tested the spacecraft systems.[76]

The orbiter's dry mass is 482.5 kg (1,064 lb) and it carried 852 kg (1,878 lb) of fuel at launch.[3][93][94] Its main engine, a derivative of the system used on India's communications satellites, uses the bipropellant combination monomethylhydrazine and dinitrogen tetroxide to achieve the thrust necessary for escape velocity from Earth. It was also used to slow down the probe for Mars orbit insertion and, subsequently, for orbit corrections.[95]

Models used for MOM:[96]

| Planetary Ephemeris | DE-424 |

| Satellite Ephemeris | MAR063 |

| Gravity Model (Earth) | GGM02C (100x100) |

| Gravity Model (Moon) | GRAIL360b6a (20x20) |

| Gravity Model (Mars) | MRO95A (95x95) |

| Earth Atmosphere | ISRO: DTM 2012 JPL : DTM 2010 |

| Mars Atmosphere | MarsGram 2005 |

| DSN Station Plate Motion | ITRF1993 frame, plate motion epoch 01-Jan-2003 00:00 UTC |

Orbit raising manoeuvres

[edit]

Several orbit raising operations were conducted from the Spacecraft Control Centre (SCC) at the ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) at Peenya, Bengaluru on 6, 7, 8, 10, 12 and 16 November by using the spacecraft's on-board propulsion system and a series of perigee burns. The first three of the five planned orbit raising manoeuvres were completed with nominal results, while the fourth was only partially successful. However, a subsequent supplementary manoeuvre raised the orbit to the intended altitude aimed for in the original fourth manoeuvre. A total of six burns were completed while the spacecraft remained in Earth orbit, with a seventh burn conducted on 30 November to insert MOM into a heliocentric orbit for its transit to Mars.[97]

The first orbit-raising manoeuvre was performed on 6 November 2013 at 19:47 UTC when the spacecraft's 440-newton (99 lbf) liquid engine was fired for 416 seconds. With this engine firing, the spacecraft's apogee was raised to 28,825 km (17,911 mi), with a perigee of 252 km (157 mi).[71]

The second orbit raising manoeuvre was performed on 7 November 2013 at 20:48 UTC, with a burn time of 570.6 seconds resulting in an apogee of 40,186 km (24,970 mi).[72][73]

The third orbit raising manoeuvre was performed on 8 November 2013 at 20:40 UTC, with a burn time of 707 seconds, resulting in an apogee of 71,636 km (44,513 mi).[72][74]

The fourth orbit raising manoeuvre, starting at 20:36 UTC on 10 November 2013, imparted a delta-v of 35 m/s (110 ft/s) to the spacecraft instead of the planned 135 m/s (440 ft/s) as a result of underburn by the motor.[75][98] Because of this, the apogee was boosted to 78,276 km (48,638 mi) instead of the planned 100,000 km (62,000 mi).[75] When testing the redundancies built-in for the propulsion system, the flow to the liquid engine stopped, with consequent reduction in incremental velocity. During the fourth orbit burn, the primary and redundant coils of the solenoid flow control valve of 440 newton liquid engine and logic for thrust augmentation by the attitude control thrusters were being tested. When both primary and redundant coils were energised together during the planned modes, the flow to the liquid engine stopped. Operating both the coils simultaneously is not possible for future operations, however they could be operated independently of each other, in sequence.[76]

As a result of the fourth planned burn coming up short, an additional unscheduled burn was performed on 12 November 2013 that increased the apogee to 118,642 km (73,721 mi),[72][76] a slightly higher altitude than originally intended in the fourth manoeuvre.[72][99] The apogee was raised to 192,874 km (119,846 mi) on 15 November 2013, 19:57 UTC in the final orbit raising manoeuvre.[72][99]

Trans-Mars injection

[edit]On 30 November 2013 at 19:19 UTC, a 23-minute engine firing initiated the transfer of MOM away from Earth orbit and on heliocentric orbit toward Mars.[25] The probe travelled a distance of 780,000,000 kilometres (480,000,000 mi) to reach Mars.[100]

Trajectory correction maneuvers

[edit]Four trajectory corrections were originally planned, but only three were carried out.[79] The first trajectory correction manoeuvre (TCM) was carried out on 11 December 2013 at 01:00 UTC by firing the 22-newton (4.9 lbf) thrusters for a duration of 40.5 seconds.[72][101] After this event, MOM was following the designed trajectory so closely that the trajectory correction manoeuvre planned in April 2014 was not required. The second trajectory correction manoeuvre was performed on 11 June 2014 at 11:00 UTC by firing the spacecraft's 22 newton thrusters for 16 seconds.[102] The third planned trajectory correction manoeuvre was postponed, due to the orbiter's trajectory closely matching the planned trajectory.[103] The third trajectory correction was also a deceleration test 3.9 seconds long on 22 September 2014.[88]

Mars orbit insertion

[edit]

The plan was for an insertion into Mars orbit on 24 September 2014,[10][104] approximately 2 days after the arrival of NASA's MAVEN orbiter.[105] The 440-newton liquid apogee motor was test fired on 22 September at 09:00 UTC for 3.968 seconds, about 41 hours before actual orbit insertion.[104][106][107]

| Date | Time (UTC) | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 23 September 2014 | 10:47:32 | Satellite communication switched to medium gain antenna |

| 24 September 2014 | 01:26:32 | Forward rotation started for deceleration burn |

| 01:42:19 | Eclipse started | |

| 01:44:32 | Attitude control manoeuvre performed with thrusters | |

| 01:47:32 | Liquid Apogee Motor starts firing | |

| 02:11:46 | Liquid Apogee Motor stops firing |

After these events, the spacecraft performed a reverse manoeuvre to reorient from its deceleration burn and entered Martian orbit.[9][108][4]

Gallery

[edit]Mars global and local views

[edit]Results

[edit]Observation of suprathermal argon in exosphere

[edit]The Mars Exospheric Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA) reported altitude profiles of argon-40 in the Martian exosphere from four orbits during December 2014 when the periapsis of the spacecraft was lowest. The upperlimit of the argon number density corresponding to this period is almost 5 x 105/cm3 at an altitude of 250 km and the typical scale height is around 16 km corresponding to an exospheric temperature of around 275 K. However, on two orbits, the scale height over this altitude region is found to increase significantly making the effective temperature greater than 400 K. The observations of Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer (NGIMS) onboard the MAVEN also indicate that the change in slope in argon density occurs near the upper exosphere of around 230–260 km. These observations indicate significant suprathermal populations of carbon dioxide and argon in the Martian exosphere.[109][110][111]

Global apparent short wave infrared albedo mapping

[edit]

Global apparent short wave infrared (SWIR) albedo mapping of Mars was executed based on data acquired from the Methane Sensor for Mars (MSM) payload. The instrument is a differential radiometer in SWIR region of spectrum that measures reflected solar radiance in two SWIR (1.64 to 1.66 μm) channels. The first one is a methane channel which measures the absorption by methane and second one is a no absorption channel (reference channel). The reference channel data acquired from October 2014 to February 2015 was used for apparent SWIR albedo mapping. Data less than one degree of the limb of the planet was discarded to avoid atmospheric limb brightening and to ensure that the field of view was entirely on the planet. Data with incidence and zolar zenith angle greater than 60° was also discarded to reduce atmospheric effects.[112][113]

The bright regions having an albedo greater than 0.4 are mainly localised over the Tharsis plateau, Arabia Terra, and Elysium Planitia and generally represent surface covered by dust while the low albedo of less than 0.15 are mainly localised over Syrtis Major Planum, Daedalia Planum, Valles Marineris and Acidalia Planitia. The low albedo is associated with dark surfaces having volcanic rock basalt as surface expostures. Weekly mean apparent albedo data over Syrtis Major Planum was recorded in a period of solar longitudes 205 to 282 (October 2014) during which dust activities are significant. A surge in mean albedo from the usual 0.2 to an erratically higher near 0.4 was recorded on solar longitude 225 which was possibly due to the local injection of dust into atmosphere.[112] This matches with a similar albedo spike in the region during solar longitude of 280–290 recorded by Viking IRTM.[114]

Neutral composition of evening time exosphere

[edit]The Mars Exosphere Neutral Composition Analyser (MENCA) during 18–29 December 2014 provided altitude profiles of three major constituents; carbon dioxide (amu 44), nitrogen molecule & carbon monoxide (amu 28) and atomic oxygen (amu 16) in the Martian exosphere. This measurents were taken from four orbits which were closest to Mars with a periapsis which varied from 262–265 km during the evening time or close to sunset terminator hours to attain moderate solar activity conditions.[115][116]

During evening hours the carbon dioxide density changes from 3.5 × 107 cm to 1.5 × 105/cm3 for an altitude change of 100 km in the exosphere. The number density of amu 28 is comparable to that of carbon dioxide (amu 44) at lower altitudes and exceeds above 275 km. The factor becomes almost 10 at 375 km. The atomic oxygen number density exceeds that of carbon dioxide above 270 km. At 335 km, this difference becomes a factor of 10, above which atomic oxygen far exceeds the abundance of carbon dioxide. The transition from carbon dioxide to atomic oxygen dominant exosphere is an important indicator of the solar EUV forcing. The mean exospheric temperature derived using the scale height values estimated from the observed partial pressure variation in the three mass channels is 271 ± 5 K. These first observations corresponding to the Martian evening hours is expected to provide constraints data to the thermal escape models.[115][117]

Radio occultation experiment on solar corona

[edit]

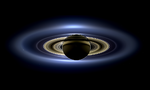

Radio occulation experiments were performed using S-band downlink signals from the spacecraft during the May–June 2015 (post-maxima of solar cycle 24) period when the Sun was between Earth and Mars along a line in the same elliptical plane. The downlink signals from the spacecraft of frequency 2.29 GHz passed through the solar coronal region at solar offset distances between 4–20 solar radius.[118][116]

The experiment was conducted in a closed-loop one-way format at a sampling frequency of one hertz and the occultation geometry was such that the proximate ray path from the spacecraft to Earth covered a range of 5−39 degree heliolaltitudes. From observations with radio signals from the spacecraft, it is found that the turbulence power spectrum at larger heliocentric distances greater than 10 R☉ (18.17 R☉ on 28 May), the curve steepens with a spectral index of around 0.6−0.8. For smaller heliocentric distances of less than 10 R☉ (5.33 R☉ on 10 June), it displays flattening in lower-frequency regions with a spectral index of around 0.2−0.4, which corresponds to a solar wind acceleration region. A complimentary observation is that the higher-heliolatitude spectra appear to be flatter than lower-heliolatitude spectra.[118][119]

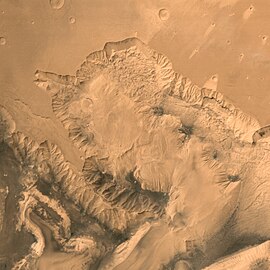

Atmospheric optical depth in the Valles Marineris

[edit]Stereo images of Valles Marineris acquired by Mars Colour Camera (MCC) payload along with the co-registered MOLA Digital Elevation Map (DEM) were used to calculate atmospheric optical depth (AOD) over northern and southern walls of Valles Marineris. On northern wall ranging from 62°W to 68°W, the red channel of MCC measured an AOD of 1.7 near the bottom of the valley and decreases monotonically to about 1.0 near the top, while the green channel measures an AOD of around 2.1 and similarly decreases monotonically with increasing altitude. Both measurements shows a clear relation that can be well fitted with an exponential curve. The calculated scale height of AOD equals to 14.08 km and 11.24 km for red and green channels respectively.[120]

The red channel AOD measurement on the southern wall of Valles Marineris ranging from 62°W to 68°W remains nearly steady from 1.75 in the bottom of the valley to 1.85 near to the top and does not show a monotonic decline of AOD with altitude. From the AOD map overlaid on MCC image draped on MOLA DEM, it is clear that there is a mountain-like structure along the southern walls of the valley, which is expected to cause the creation of banner clouds in the lee side of the mountain or lee wave clouds. The AOD variation with altitude along the southern wall between the longitudes 57°W to 62°W where mountain structures are not present shows a normal monotonic decrease. This further supports the existence of lee wave clouds on the southern wall of Valles Marineris around 65°W.[120][121]

Status

[edit]The orbit insertion put MOM in a highly elliptical orbit around Mars, as planned, with a period of 72 hours 51 minutes 51 seconds, a periapsis of 421.7 km (262.0 mi) and apoapsis of 76,993.6 km (47,841.6 mi).[9] At the end of the orbit insertion, MOM was left with 40 kg (88 lb) of fuel on board, more than the 20 kg (44 lb) necessary for a six-month mission.[122]

On 28 September 2014, MOM controllers published the spacecraft's first global view of Mars. The image was captured by the Mars Colour Camera (MCC).[123]

On 7 October 2014, the ISRO altered MOM's orbit so as to move it behind Mars for comet Siding Spring's flyby of the planet on 19 October 2014. The spacecraft consumed 1.9 kg (4 lb) of fuel for the manoeuvre. As a result, MOM's apoapsis was reduced to 72,000 km (45,000 mi).[124] After the comet passed by Mars, ISRO reported that MOM remained healthy.[125]

On 4 March 2015, the ISRO reported that the MSM instrument was functioning normally and are studying Mars' albedo, the reflectivity of the planet's surface. The Mars Colour Camera was also returning new images of the Martian surface.[126][127]

On 24 March 2015, MOM completed its initial six-month mission in orbit around Mars. ISRO extended the mission by an additional six months; the spacecraft has 37 kg (82 lb) of propellant remaining and all five of its scientific instruments are working properly.[128] The orbiter can reportedly continue orbiting Mars for several years with its remaining propellant.[129]

A 17-day communications blackout occurred from 6 to 22 June 2015 while Mars' orbit took it behind the Sun from Earth's view.[53]: 52

On 24 September 2015, ISRO released its Mars Atlas, a 120-page scientific atlas containing images and data from the Mars Orbiter Mission's first year in orbit.[130]

In March 2016, the first science results of the mission were published in Geophysical Research Letters, presenting measurements obtained by the spacecraft's MENCA instrument of the Martian exosphere.[131][132]

During 18 to 30 May 2016, a communication whiteout occurred with Earth coming directly between Sun and Mars. Due to high solar radiation, sending commands to spacecraft was avoided and payload operations were suspended.[133]

On 17 January 2017, MOM's orbit was altered to avoid the impending eclipse season. With a burn of eight 22 N thrusters for 431 seconds, resulting in a velocity difference of 97.5 metres per second (351 km/h) using 20 kilograms (44 lb) of propellant (leaving 13 kg remaining), eclipses were avoided until September 2017. The battery is able to handle eclipses of up to 100 minutes.[134]

On 19 May 2017, MOM reached 1,000 days (973 sols) in orbit around Mars. In that time, the spacecraft completed 388 orbits of the planet and relayed more than 715 images back to Earth. ISRO officials stated that it remains in good health.[135]

On 24 September 2018, MOM completed 4 years in its orbit around Mars, although the designed mission life was only six months. Over these years, MOM's Mars Colour Camera has captured over 980 images that were released to the public. The probe is still in good health and continues to work nominally.[136]

On 24 September 2019, MOM completed 5 years in orbit around Mars, sending 2 terabytes of imaging data, and had enough propellant to complete another year in orbit.[137]

On 1 July 2020, MOM was able to capture a photo of the Mars satellite Phobos from 4200 km away.[138]

On 18 July 2021 Mars Colour Camera (MCC) captured full disc image of Mars from an altitude of about 75,000 km with spatial resolution about 3.7 km.[139]

In October 2022, ISRO announced that it had lost communications with MOM in April 2022, a time when the spacecraft faced increasingly longer duration eclipses, including a seven-hour long eclipse that it was not designed to withstand. ISRO said the spacecraft had likely run out of attitude control propellant and was therefore not recoverable.[31][30][29]

Recognition

[edit]

In 2014, China referred to India's successful Mars Orbiter Mission as the "Pride of Asia".[140] The Mars Orbiter Mission team won US-based National Space Society's 2015 Space Pioneer Award in the science and engineering category. NSS said the award was given as the Indian agency successfully executed a Mars mission in its first attempt; and the spacecraft is in an elliptical orbit with a high apoapsis where, with its high resolution camera, it is taking full-disk colour imagery of Mars. Very few full disk images have ever been taken in the past, mostly on approach to the planet, as most imaging is done looking straight down in mapping mode. These images will aid planetary scientists.[141][142][143]

An illustration of the Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft is featured on the reverse of the ₹2,000 currency note of India.[144]

An image taken by the Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft was the cover photo of the November 2016 issue of National Geographic magazine, for their story "Mars: Race to the Red Planet".[145][146]

Follow-up mission

[edit]ISRO plans to develop and launch a follow-up mission called Mars Orbiter Mission 2 (MOM-2 or Mangalyaan-2) with a greater scientific payload to Mars in 2024.[147][148][149] The orbiter will use aerobraking to reduce apoapsis of its initial orbit and reach an altitude more suitable for scientific observation.[150]

In popular culture

[edit]- The 2019 Hindi film Mission Mangal is loosely based on India's mission to Mars.[151][152]

- A web series called Mission Over Mars is loosely based on India's Mars mission.[153][154]

- Space MOMs, released online in 2019, is based on India's Mars mission.[155]

- Mission Mars: Keep Walking India is a short film released in 2018 based on India's Mars mission.[156][157]

See also

[edit]- Department of Space – Indian government space program administrator

- ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter – Mars orbiter, part of ExoMars programme

- Venus Orbiter Mission

- List of ISRO missions

- List of Mars orbiters

- List of missions to Mars

- Mars Express – European orbiter mission to Mars (2003–present)

References

[edit]- ^ "Mars Orbiter Spacecraft completes Engine Test, fine-tunes its Course". Spaceflight 101. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mars Orbiter Mission Spacecraft". Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 December 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e S. Arunan; R. Satish (25 September 2015). "Mars Orbiter Mission spacecraft and its Challenges" (PDF). Current Science. 109 (6): 1061–1069. doi:10.18520/v109/i6/1061-1069.

- ^ a b Lakshmi, Rama (24 September 2014). "India becomes first Asian nation to reach Mars orbit, joins elite global space club". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Spacecraft's Orbit Raised". Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d "India to launch Mars Orbiter Mission on November 5". The Times of India. Times News Network. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter Mission: Launch Vehicle". ISRO. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Update on the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM)". isro.gov.in. ISRO. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mars Orbiter Spacecraft Successfully Inserted into Mars Orbit" (Press release). ISRO. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014.

- ^ a b Tucker, Harry (25 September 2014). "India becomes first country to enter Mars' orbit on their first attempt". Herald Sun. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ I Interviewed ISRO Chief S Somanath | Chandrayaan 3 (He mentioned official name is not Mangalyaan but just MOM or Mars Orbiter Mission), 10 July 2023, retrieved 14 July 2023

- ^ "Mangalyaan". NASA. 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Wall, Mike (23 September 2014). "India's First Mars Probe Makes Historic Red Planet Arrival". Space.com.

The MOM probe, which is named Mangalyaan (Sanskrit for "Mars craft"), executed a 24-minute orbital insertion burn Tuesday night, ending a 10-month space journey that began with the spacecraft's launch on Nov. 5, 2013

- ^ a b Walton, Zach (15 August 2012). "India Announces Mars Mission One Week After Landing". Web Pro News. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Manmohan Singh formally announces India's Mars mission". The Hindu. Press Trust of India. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Bal, Hartosh Singh (30 August 2012). "BRICS in Space". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Patairiya, Pawan Kumar (23 November 2013). "Why India Is Going to Mars". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "India's Mars Shot". The New York Times. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Chang, Jon M. (5 November 2013). "India Launches Mars Orbiter Mission, Heralds New Space Race". ABC News. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Burke, Jason (24 September 2014). "India's Mars satellite successfully enters orbit, bringing country into space elite". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

India has become the first nation to send a satellite into orbit around Mars on its first attempt, and the first Asian nation to do so.

- ^ Lakshmi, Rama (24 September 2014). "India becomes first Asian nation to reach Mars orbit, joins elite global space club". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

India became the first Asian nation to reach the Red Planet when its indigenously made unmanned spacecraft entered the orbit of Mars on Wednesday

- ^ Park, Madison (24 September 2014). "India's spacecraft reaches Mars orbit ... and history". CNN. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

India's Mars Orbiter Mission successfully entered Mars' orbit Wednesday morning, making India the first nation to arrive on its first attempt and the first Asian country to reach the Red Planet.

- ^ Harris, Gardiner (24 September 2014). "On a Shoestring, India Sends Orbiter to Mars on Its First Try". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "India's Mars Mission Mangalyaan to be launched on November 5". Bihar Prabha. 22 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Mission: Latest Updates". ISRO. 2 December 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Mission: Mission Objectives". ISRO. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ a b Amos, Jonathan (24 September 2014). "Why India's Mars mission is so cheap – and thrilling". BBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

Its measurements of other atmospheric components will dovetail very nicely with Maven and the observations being made by Europe's Mars Express. "It means we'll be getting three-point measurements, which is tremendous."

- ^ "Mangalyaan successfully placed into Mars Transfer Trajectory". Bihar Prabha. 1 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Chethan (2 October 2022). "Designed to last six months, India's Mars Orbiter bids adieu after 8 long years". The Times of India. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ a b "With drained battery & no fuel, India's Mars Orbiter craft quietly bids adieu". Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Science Programme Office (SPO), ISRO Headquarters". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

It was also discussed that despite being designed for a life-span of six months as a technology demonstrator, the Mars Orbiter Mission has lived for about eight years in the Martian orbit with a gamut of significant scientific results on Mars as well as on the Solar corona, before losing communication with the ground station as a result of a long eclipse in April 2022. During the national meet, ISRO deliberated that the propellant must have been exhausted, and therefore, the desired attitude pointing could not be achieved for sustained power generation. It was declared that the spacecraft is non-recoverable, and attended its end-of-life. The mission will be ever-regarded as a remarkable technological and scientific feat in the history of planetary exploration.

- ^ Hindustan Times. "Mangalyaan mission is dead! ISRO Mars Orbiter breaks Indian hearts; it was truly SPECIAL". MSN. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022.

- ^ "UPDATE ON THE MARS ORBITER MISSION (MOM) AND THE NATIONAL MEET ORGANISED ON 27 SEPTEMBER, 2022". Indian Space Research Organisation, Department of Space (Press release). 3 October 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ "After Chandrayaan, its mission to Mars: Madhavan Nair". Oneindia. United News of India. 23 November 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Manmohan Singh formally announces India's Mars mission". The Hindu. Press Trust of India. 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Cabinet clears Mars mission". The Hindu. 4 August 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ a b "India's Mars mission gets Rs. 125 crore". Mars Daily. Indo-Asian News Service. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "We are planning to send our first orbiter to Mars in 2013". Deccan Chronicle. 12 August 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Pramit Pal (6 November 2013). "Rocket science: how ISRO flew to Mars cheap". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b "India plans mission to Mars next year". The Daily Telegraph. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ a b Laxman, Srinivas (6 August 2013). "Isro kicks off Mars mission campaign with PSLV assembly". The Times of India. Times News Network. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Bagla, Pallava (3 October 2013). "India's Mission Mars: The journey begins". NDTV. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ^ "How ISRO modified a lunar orbiter into Mars orbiter Mangalyaan, India's 'Moon Man' recalls". Zee News. 25 October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "NASA Reaffirms Support for Mars Orbiter Mission" (Press release). ISRO. 5 October 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- ^ "U.S., India to Collaborate on Mars Exploration, Earth-Observing Mission" (Press release). NASA. 30 September 2014. Release 14-266. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ "ISRO scientists who made Mangalyaan possible: All you need to know about them". 25 September 2014.

- ^ "India Successfully Launches First Mission to Mars; PM Congratulates ISRO Team". International Business Times. 5 November 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Bhatt, Abhinav (5 November 2013). "India's 450-crore mission to Mars to begin today: 10 facts". NDTV. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Vij, Shivam (5 November 2013). "India's Mars mission: worth the cost?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Rai, Saritha (7 November 2013). "How India Launched Its Mars Mission At Cut-Rate Costs". Forbes. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ "The secret behind India's budget-friendly moonshots: How ISRO has developed its low-cost edge". The Economic Times. 24 August 2023. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ a b David, Leonard (16 October 2013). "India's First Mission to Mars to Launch This Month". Space.com. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lele, Ajey (2014). Mission Mars: India's Quest for the Red Planet. Springer. ISBN 978-81-322-1520-2.

- ^ rajasekhar, pathri (2 March 2022). "ISRO scientists study Sun using Mangalyaan". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Mars Orbiter Mission Spacecraft. Archived 5 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine ISRO. Accessed on 18 August 2019.

- ^ Uma, BR; Sankaran, M.; Puthanveettil, Suresh E. (2016). "Multijunction Solar Cell Performance in Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) conditions" (PDF). E3S Web of Conferences. 16: 04001. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/20171604001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter Mission: Major Challenges". ISRO. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ Savitha, A.; Chetwani, Rajiv R.; Ravindra, M.; Baradwaj, K. M. (2015). Onboard processor validation for space applications. 2015 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics. 10–13 August 2015. Kochi, India. doi:10.1109/ICACCI.2015.7275677.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Mission: Payloads". ISRO. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Chellappan, Kumar (11 January 2013). "Amangal to budget from Mangalyaan, say experts". Daily Pioneer. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ^ "Mars mission gets October, 2013 launch date deadline as India reaches out to the stars". The Indian Express. Press Trust of India. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ Klotz, Irene (7 December 2016). "India's Mars Orbiter Mission Has a Methane Problem". Seeker. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Global Albedo Map of Mars". Indian Space Research Organisation. 14 July 2017. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "India's Mars Orbiter Mission Has a Methane Problem". space.com. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "Bangalore centre to control Mars orbiter henceforth". Deccan Herald. Deccan Herald News Service. 6 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ Madhumathi, D.S. (6 November 2013). "Mars baton shifts to ISTRAC". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Mars orbiter well on its way". The Hindu. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Jayaraman, K.S. (28 June 2013). "NASA's Deep Space Network to Support India's Mars Mission". Space.com. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ Rao, Ch. Sushil (3 December 2013). "Mars mission: India gets help from South Africa to monitor 'Mangalyaan'". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ a b "Mars Mission on track; orbit to be raised on Thursday". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b Ram, Arun (7 November 2013). "Isro scientists raise orbit of Mars spacecraft". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Mars Orbiter Mission: Latest Updates". ISRO. 8 November 2013. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Second orbit raising manoeuvre on Mars Mission performed". Indian Express. Press Trust of India. 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b Kaping, Philaso G. (9 November 2013). "India's Mars probe performs third orbit raising manoeuvre". Zee News. Zee Media Bureau.

- ^ a b c Rao, Ch. Sushil (11 November 2013). "Mars mission faces first hurdle, 4th orbit-raising operation falls short of target". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ a b c d Rao, Ch. Sushil (11 November 2013). "Mars mission: After glitch, Isro plans supplementary orbit-raising operation tomorrow". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ Srivastava, Vanita (1 December 2013). "300 days to Mars: Countdown begins for India". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "Isro's Mars Orbiter Mission successfully placed in Mars transfer trajectory". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Lakdawalla, Emily (30 November 2013). "Mars Orbiter Mission ready to fly onward from Earth to Mars". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b "ISRO successfully performs first TCM on Mars Orbiter". Zee News. Press Trust of India. 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b Bagla, Pallava (11 December 2013). Ghosh, Shamik (ed.). "Mangalyaan's next successful step: a tricky mid-course correction". NDTV.

- ^ a b c d e "Mars orbiter gets its first course correction". The Hindu. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "ISRO's Mars Orbiter spacecraft has..." ISRO's Mars Orbiter Mission. Facebook.com. 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter Spacecraft Crosses Half Way Mark of its Journey" (Press release). ISRO. 9 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- ^ Ganesan, S. (2 March 2014). "Health parameters of Mars Orbiter are normal". The Hindu.

- ^ "Trajectory correction of Mars mission likely by June 11". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 2 June 2014. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014.

- ^ Srivastava, Vanita (1 August 2014). "Mangalyaan on track, no path correction in August". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Spacecraft's Main Liquid Engine Successfully Test Fired" (Press release). ISRO. 22 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

- ^ a b Lakdawalla, Emily (31 October 2013). "India prepares to take flight to Mars with the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM)". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ "India prepares to return troubled rocket to flight". www.planetary.org. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Isro's Mars Mission: Why Mangalyaan's path is full of riders". Tech2. 6 November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Ram, Arun (7 November 2013). "Mars mission: Scientists start raising Mangalyaan's orbit". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ "MARS Orbiter Mission". www.ursc.gov.in. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ Ians (15 September 2014). "India to enter Mars orbit on September 24". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "ISRO successfully test-fires vital engine; Mars orbiter on final lap". www.downtoearth.org.in. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "A journey with MOM" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (23 September 2014). "India's MOM spacecraft arrives at Mars". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (10 November 2013). "A hiccup in the orbital maneuvers for Mars Orbiter Mission". The Planetary Society.

- ^ a b "Mars mission: Isro performs last orbit-raising manoeuvre". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 16 November 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (5 November 2013). "Indian spacecraft soars on historic journey to Mars". Spaceflight Now.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter spent 55% of the total fuel so far: ISRO scientist". The Indian Express. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "ISRO performs TCM-2 on Mars Orbiter Mission". The Economic Times. Press Trust of India. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Srivastava, Vanita (1 August 2014). "Mangalyaan on track, no path correction in August". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ a b Rao, V. Koteswara (15 September 2014). "Mars Orbit Insertion" (PDF). ISRO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2014.

- ^ David, Leonard (15 October 2013). "India's First Mission to Mars to Launch This Month". Space.com.

- ^ Singh, Ritu (22 September 2014). "Mars Orbiter Mission: ISRO to test fire engine today". Zee News. Zee Media Bureau. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Ram, Arun (22 September 2014). "Mars spacecraft test-fired successfully, to enter red planet's orbit on Wednesday". The Times of India. Times News Network.

- ^ "India's Maiden Mars Mission Makes History". Bloomberg TV India. 24 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Bhardwaj, Anil; Thampi, Smitha V.; Das, Tirtha Pratim; Dhanya, M.B.; Naik, Neha; Vajja, Dinakar Prasad; Pradeepkumar, P.; Sreelatha, P.; Abhishek J., K.; Thampi, R. Satheesh; Yadav, Vipin K.; Sundar, B.; Nandi, Amarnath; Padmanabhan, G. Padma; Aliyas, A.V. (1 March 2017). "Observation of suprathermal argon in the exosphere of Mars". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (5): 2088–2095. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.2088B. doi:10.1002/2016GL072001. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ "ISRO preparing second mission to Mars: Report". The Week. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Update on the Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM)". www.isro.gov.in. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b Mishra, Manoj Kumar (1 January 2017). "SWIR Albedo Mapping of Mars Using Mars Orbiter Mission Data". Current Science.

- ^ "Global Albedo Map of Mars". www.isro.gov.in. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "Mars Global Data Sets: IRTM Albedo". www.mars.asu.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b On the evening time exosphere of Mars, Result from MENCA aboard Mars Orbiter Mission. "Researchgate". Researchgate.

- ^ a b "Mars Orbiter Mission". www.isro.gov.in. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ "ISRO Mars Orbiter Mission – Nov 2013 launch to September 2014 arrival – Updates". forum.nasaspaceflight.com. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ a b M.V. Roopa, Richa N. Jain, R.K. Choudhary, Anil Bhardwaj, Umang Parikh, Bijoy K. Dai. "A study on the solar coronal dynamics during the post-maxima phase of the solar cycle 24 using S-band radio signals from the Indian Mars Orbiter Mission". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bhardwaj, Anil; Choudhary, Raj; Jain, Richa Naja (2022). "A study on the solar coronal dynamics during the post-maxima phase of the solar cycle 24 using S-band radio signals from the Indian Mars Orbiter Mission". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 511 (2): 1750. Bibcode:2022MNRAS.511.1750J. doi:10.1093/mnras/stac056.

- ^ a b Mishra, Manoj K.; Chauhan, Prakash; Singh, Ramdayal; Moorthi, S.M.; Sarkar, S.S. (1 February 2016). "Estimation of dust variability and scale height of atmospheric optical depth (AOD) in the Valles Marineris on Mars by Indian Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) data". Icarus. 265: 84–94. Bibcode:2016Icar..265...84M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.10.017. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ K., Mishra, Manoj; Prakash, Chauhan; Ramdayal, Singh; M., Moorthi, S.; S., Sarkar, S. (2016). "Estimation of dust variability and scale height of atmospheric optical depth (AOD) in the Valles Marineris on Mars by Indian Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) data". Icarus. 265: 84. Bibcode:2016Icar..265...84M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.10.017. ISSN 0019-1035.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mars Orbiter Mission looks to sniff methane on comet". The Times of India. India. 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (29 September 2014). "Mars Orbiter Mission delivers on promise of global views of Mars". The Planetary Society.

- ^ Laxman, Srinivas (9 October 2014). "Mars Orbiter Mission shifts orbit to take cover from Siding Spring". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "I'm safe and sound, tweets MOM after comet sighting". The Hindu. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Kumar, Chethan (26 September 2014). "Mars Orbiter Mission sends fresh pictures, methane sensors are working fine". The Times of India. Times News Network. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (4 March 2015). "Mars Orbiter Mission Methane Sensor for Mars is at work". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter Mission extended for another 6 months". India Today. Indo-Asian News Service. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Mangalyaan can survive for 'years' in Martian orbit: ISRO chief". The Indian Express. Express News Service. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "ISRO releases Mars atlas to mark Mangalyaan's first birthday in space". Zee News. Zee Media Bureau. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Ahmed, Syed Maqbool (2 March 2016). "MENCA brings divine wealth from Mars: First science results from the Mars Orbiter Mission". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ Bhardwaj, Anil; Thampi, Smitha V.; Das, Tirtha Pratim; Dhanya, M.B.; Naik, Neha; et al. (March 2016). "On the evening time exosphere of Mars: Result from MENCA aboard Mars Orbiter Mission". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (5): 1862–1867. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..43.1862B. doi:10.1002/2016GL067707.

- ^ "MOM successfully came out of 'whiteout' Phase – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Long Eclipse Avoidance Manoeuvres Performed Successfully on MOM Spacecraft". Mars Daily. 24 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Vyawahare, Malavika (19 June 2017). "India's Mars Orbiter completes 1000 days in orbit and is still going strong". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) completes 4 years in its orbit". Indian Space Research Organisation. 24 September 2018. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "ISRO's Mars Mission Completes 5 Years, Was Meant To Last Only 6 Months". NDTV.com. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ "Phobos imaged by MOM on 1st July". Indian Space Research Organisation. 5 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Mars full disc image by MCC – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 29 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

Full disc of Mars was imaged by Mars Colour Camera (MCC) of MOM on 18 July 2021 from an altitude of about 75,000km from Mars. The spatial resolution of the image is about 3.7 Km. Mars is seen entering in summer solstice in the northern hemisphere and it brings changes to the Martian ice caps, much of the ice cap is seen vaporized, adding water and carbon di-oxide to the atmosphere. Afternoon clouds are visible over Tempe Terra and near Martian North Polar region. Smaller cloud patches could also be seen over Naochis Terra region in the southern hemisphere.

- ^ Sridharan, Vasudevan (24 September 2014). "China Heralds India's Mars Mission Mangalyaan as 'Pride of Asia'". International Business Times. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Brandt-Erichsen, David (12 January 2015). "Indian Space Research Organization Mars Orbiter Programme Team Wins National Space Society's Space Pioneer Award for Science and Engineering". National Space Society. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "ISRO Mars Orbiter Mission Team Wins Space Pioneer Award". NDTV. Press Trust of India. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ "2015 Space Pioneer Award was presented to ISRO for Mars Orbiter Mission". ISRO. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 banned: New Rs 2,000 currency note to feature Mangalyaan, raised bleed lines". Firstpost. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Bagla, Pallava (17 February 2017). "India eyes a return to Mars and a first run at Venus". Science.

- ^ "National Geographic (cover)". National Geographic. November 2016. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016.

- ^ Mehta, Jatan. "Mangalyaan, India's first Mars mission". Planetary Society. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Scientific Assembly Abstracts (PDF). 42nd Committee on Space Research Scientific Assembly. Pasadena, CA. 21 July 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2018.

- ^ Singh, Kanishk (28 January 2016). "India's French Connection: CNES and ISRO jointly will develop Mangalyaan 2". The TeCake. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Laxman, Srinivas (29 October 2016). "With 82 launches in a go, Isro to rocket into record books". The Times of India. Times News Network. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Gohd, Chelsea (23 August 2019). "'Mission Mangal' Tells the True Story of the Women Behind India's First Mission to Mars". Space.com. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ "Before ALTBalaji's Mission Over Mars, meet the real women behind Mars Orbiter Mission". The Indian Express. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Ekta Kapoor's MOM Mission Over Mars features wrong rocket on its poster". The Indian Express. 11 June 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Ekta Kapoor's M.O.M – Mission Over Mars Poster Has A Rocket Oopsie". NDTV.com. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ Dundoo, Sangeetha Devi (1 December 2018). "Radha Bharadwaj discusses her film 'Space MOMs', and why she's at loggerheads with Akshay Kumar's production 'Mission Mangal'". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Actor Imran Khan don's the director's hat for a short film". Hindustan Times. 11 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Johnnie Walker launches Imran Khan's directorial debut 'Mission Mars: Keep Walking India". GQ India. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Mars Orbiter Mission website Archived 10 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Mars Orbiter Mission brochure Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Current Science Vol. 109, Issue 6: Special Section on Mars Orbiter Mission with featured papers (25 September 2015)