Islamic State – Central Africa Province

| Islamic State's Central Africa Province | |

|---|---|

| ولاية وسط إفريقية | |

Logo of the Islamic State's Central Africa Province | |

| Leaders | Abu Yasir Hassan (Mozambique, until 2022) Musa Baluku (Congo) |

| Dates of operation | 2018(?) – present |

| Headquarters | Mocímboa da Praia (2020–2021) |

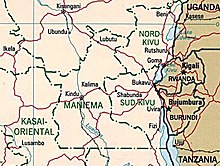

| Active regions | Mozambique (until 2022), Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda |

| Ideology | Islamic Statism |

| Size | 1,000-1,500 adult males (DRC)[1] Few hundred (Mozambique, until 2022)[2] |

| Part of | |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

| Battles and wars | Kivu conflict Ituri conflict Insurgency in Cabo Delgado (until 2022) |

The Central Africa Province[note 1] (abbreviated IS-CAP, also known as Central Africa Wilayah and Wilayat Wasat Ifriqiya) is an administrative division of the Islamic State (IS), a Salafi jihadist militant group and unrecognised quasi-state. As a result of a lack of information, the foundation date and territorial extent of the Central Africa Province are difficult to gauge, while the military strength and activities of the province's affiliates are disputed. The Central Africa Province initially covered all IS activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique and Uganda. In September 2020, during the insurgency in Cabo Delgado, IS-CAP shifted its strategy from raiding to actually occupying territory, and declared the Mozambican town of Mocímboa da Praia its capital. After this point, however, the Mozambican branch declined and was split off from IS-CAP in 2022, becoming a separate IS province; as a result, this leaves IS-CAP to operate in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda.

History

[edit]Background and foundation

[edit]Following its seizure of much territory in Syria as well as Iraq, and its proclamation of a restored caliphate, the Islamic State (IS) became internationally well known and an attractive ally to Salafi jihadist Islamist extremist and terrorist groups around the world. Several rebel groups in West Africa, Somalia and the Sahara swore allegiance to IS; these factions grew in importance as IS's core faction in the Middle East declined. Despite the growing importance of pro-IS groups in western, northern, and eastern Africa, no major IS faction sprang up in central and southern Africa for years.[3] A faction known as the "Islamic State in Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda" was set up in April 2016, but was only active in Somalia as well as Kenya for a short time.[4]

In October 2017, a video which showed a small number of militants in the Democratic Republic of the Congo who claimed to be members of the "City of Monotheism and Monotheists" (MTM) group was posted on pro-IS channels. The leader of the militants went on to say that "this is Dar al-Islam of the Islamic State in Central Africa" and he asked other like-minded individuals to travel to MTM territory, join the militants and fight the war against the government. The Long War Journal noted that though this pro-IS group in Congo appeared to be very small, its emergence had gained a notable amount of attention from IS sympathizers.[5] There were subsequently disputes about the nature of MTM. The Congo Research Group (CRG) argued in 2018 that MTM was in fact part of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), an Islamist group that has waged an insurgency in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo as well as neighboring Uganda for decades. Some experts believed that the ADF had begun to cooperate with IS, and that MTM was its attempt to publicly garner support from Islamic State loyalists.[6] IS-Central probably began to finance the ADF through a Kenyan Waleed Ahmed Zein, in this year.[7] IS's self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi first mentioned a "Central Africa Province" in a speech in August 2018, suggesting that this branch already existed beforehand.[8]

By mid-2018, the African Union claimed that Islamic State militants had infiltrated northern Mozambique, where the Islamist rebels of Ansar al-Sunna[a] had already waged an insurgency since 2017.[10] In May 2018, some Mozambican rebels posted a photo of themselves posing with a black flag which was used by IS, but also other Jihadist groups. Overall, the presence of IS in Mozambique remained disputed at the time,[9] and the country's police strongly denied that Islamic State loyalists were active in the area.[11]

Public emergence

[edit]

Several Jihadist news outlets such as the Amaq News Agency, Nashir News Agency, and Al-Naba newsletter declared in April 2019 that the Islamic State's "Central Africa Province" had carried out attacks in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. This marked the first time that IS-CAP had actually emerged as a tangible entity.[8][12] The first purported raids by IS's Central Africa Province targeted the Congolese Armed Forces (FARDC) at the village of Kamango and a military base at Bovata on 18 April; both localities are near Beni, close to the border with Uganda.[3] It remained unclear how many militants in the Congo had actually joined IS;[8] journalist Sunguta West regarded the declaration of the Central Africa Province as an attempt by a weakened IS "to boost its ego and project strength" after its defeats in Syria and Iraq.[13] A photo released by the Al-Naba newsletter showed about 15 purported IS-CAP members. The Defense Post argued that one splinter faction of the ADF had possibly joined IS-CAP, while the ADF's official leadership had made no bay'ah ("oath of allegiance") to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi or IS in general.[8] Researcher Marcel Heritier Kapiteni generally doubted whether Islamic State followers had been involved in the attacks at all, arguing that IS-CAP might be no more than a propaganda tool in a "media war". According to him, "DRC's terrain is not socially favorable to radical Islam".[14] However, a propaganda video was published in June 2019 that showed ADF leader Musa Baluku pledging allegiance to IS.[15]

On 4 June 2019, IS claimed that its Central African Province had carried out a successful attack on the Mozambique Defence Armed Forces (FADM) at Mitopy in the Mocímboa da Praia District, Mozambique.[16] At least 16 people were killed and about 12 wounded during the attack. By this point, IS considered Ansar al-Sunna as one its affiliates, though how many Islamist rebels in Mozambique were actually loyal to IS remained unclear.[17] The Defense Post argued that it was impossible to judge whether the attack had been carried out by IS-CAP or another armed group due to the lack of information on the rebels in Mozambique. In any case, the Mozambique police once again denied that any IS elements were active in the country.[9] In October 2019, IS-CAP carried out two ambushes against Mozambican security forces and allied Russian Wagner Group mercenaries in Cabo Delgado Province, reportedly killing 27 soldiers.[18] In contrast to its growing presence in Mozambique, IS-CAP's operations in the Congo remained small in scale and number by late 2019. Researcher Nicholas Lazarides argued that this proved the ADF's non-alignment with IS, suggesting that IS-CAP was indeed just a splinter faction.[19] Accordingly, the Central Africa Province's main importance laid in its propaganda value and its future potential to grow through its connections with the well-established, well-known IS core group.[20]

Increased activity in Mozambique and the Congo and split in the ADF

[edit]The Central Africa Province officially pledged allegiance to IS's new caliph Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi on 7 November 2019.[21] On 7 April 2020, IS-CAP fighters massacred 52 civilians in Xitaxi village of northern Mozambique when they refused to join their forces. Later that month, the Mozambican authorities admitted for the first time that Islamic State followers were active in the country.[22] On 27 June, IS-CAP troops occupied the town of Mocímboa da Praia for a short time, causing many locals to flee.[23] The Islamic State's al-Naba newsletter consequently touted IS-CAP's alleged successes in Mozambique, claiming that the "Crusader Mozambique army" and the "mercenaries of the Crusader Russian intelligence apparatus" (a.k.a. the Wagner Group) were being driven back by the local Islamic State forces.[24] By this time, South Africa had sent special forces to assist the Mozambican security forces against the rebels, including IS-CAP.[25]

In addition, IS-CAP greatly increased its attacks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 33 operations from mid-April to July. Its most notable strike took place on 22 June, when Islamic State fighters ambushed Indonesian MONUSCO peacekeepers near Beni, killing one and injuring another.[26] On 11 August 2020, IS-CAP defeated the Mozambique Defence Armed Forces and once more managed to take over the town of Mocimboa da Praia in a major offensive. The Jihadists also proclaimed to have captured several other settlements as well as two military bases around the town, seizing significant amounts of weaponry and ammunition.[27] The rebels subsequently declared Mocímboa da Praia the capital of their province, and further expanded their holdings by capturing several islands in the Indian Ocean during September, with Vamizi Island being the most prominent. All locals were forced to leave the islands, and the local luxury hotels were all torched.[28] At this point, IS-CAP had become one of the "most significant provinces" of IS in Africa.[29]

In September 2020, a propaganda video was published in which Musa Baluku declared that the ADF had ceased to exist and had been succeeded by IS-CAP.[30] At this point, a "major faction" of the ADF had joined Baluku in becoming part of IS,[31] while a smaller splinter remained loyal to the ideals of ex-ADF leader Jamil Mukulu[32] and later adopted the name "Pan-Ugandan Liberation Initiative" (PULI).[33] The International Crisis Group contended that the rival factions had also split geographically, with some elements moving to the Rwenzori Mountains, while others had relocated into Ituri Province.[34]

On 20 October, IS-CAP forces managed to free over 1,335 prisoners at Kangbayi central prison in Beni, making this attack one of the largest IS prison breakouts in years.[35] Despite such successes, the Congolese IS-CAP had not been able to significantly expand its presence by late 2020.[36] In contrast, IS-CAP took part in an assault on the town of Palma in Mozambique in late March 2021. Even though the rebels retreated from the settlement after the Mozambican security forces counter-attacked in early April, the battle left Palma mostly destroyed and a large number of civilians dead. IS-CAP retreated with much loot, and the conflict observatory Cabo Ligado concluded that the battle was an overall victory for the rebels.[37]

Growth of the Congolese branch, setbacks for the Mozambican wing, and official division of the province

[edit]

The Islamic State claimed responsibility for two bombings in June 2021. In Beni, a Ugandan man detonated explosives at a busy intersection, while two people were injured when an explosive device was detonated inside a Catholic church.[38] According to a Congolese military spokesman, the suicide bomber was identified as an ADF member, showing the group's allegiance to IS-CAP. The bombings were the first of their kind in Beni, leading to worries that IS-CAP was increasingly using typical Islamic State tactics. The Congolese government closed major public spaces for two days and imposed restrictions on public meetings as a precaution against further attacks.[39] In August 2021, joint Mozambican-Rwandan forces were able to retake Mocímboa da Praia as part of an offensive.[40] The Mozambican IS-CAP forces relocated their headquarters to the "Siri" base near Messalo River.[41]

However, while the Mozambican IS-CAP branch was retreating, the Congolese IS loyalists were expanding their area of operations as part of two offensives in Ituri Province. The Congolese IS-CAP also began involve itself in the Ituri conflict's local disputes, siding with Banyabwisha (a Hutu group) against other local ethnic groups, causing one village of Banyabwisha to declare allegiance to the Islamic State. The group also began to more actively proselytize locals to convert them to Islam. The Long War Journal researchers Caleb Weiss and Ryan O'Farrell argued that this might hint at an attempt by IS-CAP to build a genuine local support base which the older ADF had traditionally lacked.[42] On 8 October, IS-CAP claimed its first attack in Uganda when its forces bombed a police post in Kawempe. This marked that start of a bombing campaign in and around Kampala lasting until November, as IS affiliates and one ADF member launched several suicide attacks.[43][44] Meanwhile, security forces arrested a group of suspected IS-CAP members in Rwanda's capital Kigali; Weiss and O'Farrell speculated that this group had planned attacks in "revenge" for the Rwandan operations against the Mozambican IS forces.[44] Overall, the Congolese branch appears to have undergone a transformation in the course of 2021, adapting its strategies to match those of IS more closely. It also greatly increased its attacks on civilians.[7]

By the end of 2021, IS-CAP had suffered major setbacks in Mozambique, having lost most of its holdings and many members. However, the group reorganized as splinter cells and continued to wage a guerrilla campaign in early 2022.[45] Meanwhile, the Congolese branch increased its activity, repeatedly raiding Beni and bombing Goma.[46] Its operations faced growing resistance due to Operation Shujaa, however, an offensive launched by Uganda and its allies in eastern Congo. Several IS-CAP leaders were captured during this operation.[47] In April 2022, IS-CAP's Congolese branch released a video message, showing the group pledging allegiance to Abu al-Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurashi who had been appointed as new IS caliph after the death of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. In the video, Musa Baluku declared that IS-CAP was undeterred by the deaths of its leaders and would continue its insurgency.[48] By mid-2022, the Congolese branch of IS-CAP was described as being much more active as in previous years.[49] The province was reportedly reorganized by the IS central command in May, with the Congolese and Mozambican branches being declared autonomous;[50] the latter was subsequently declared the "Mozambique Province".[51]

Activity after the division

[edit]In October 2022, IS-CAP made headlines when militants attacked a Catholic mission in the village of Maboya, setting fire to infrastructure, including a hospital. A Catholic nun, Marie-Sylvie Kavuke Vakatsuraki, was burned to death in the hospital, where she worked as a doctor. A patient also died.[52] At this point, the Congolese forces of IS-CAP had greatly increased their area of operations, grown in numbers, and freed over 2,000 prisoners.[50] By late 2022, IS-CAP had reduced its activity, but it once again increased the rate of its attacks in early 2023.[53] However, the Islamic State forces were increasingly pushed out of their strongholds by the Ugandan and Congolese troops engaged in Operation Shujaa. Regardless, IS-CAP troops managed to destroy PULI, the ADF splinter group which had refused to pledge loyalty to the Islamic State, in January 2023. PULI's survivors, including one of Mukulu's sons, mostly agreed to join IS-CAP after their defeat.[33]

In July 2023, insurgents killed 42 people in the Mpondwe school massacre in western Uganda. The attack was attributed to IS-linked ADF militants,[54][55] and later specifically IS-CAP. However, neither IS-Central nor IS-CAP officially claimed the operation as their own; researcher Jacob Zenn concluded that the Islamic State's leadership probably "viewed the school massacre as beyond the pale even for IS, and harmful for IS's reputation globally" and thus wanted to avoid any direct associations.[46] By 2024, IS-CAP's ability to operate was increasingly suffering under the continued pressure of Operation Shujaa, noticeably degrading its rate of attacks as well as propaganda output.[56]

Organization

[edit]According to expert Jacob Zenn, the Congolese and Mozambican elements of IS-CAP initially constituted two "wings" of the province. Both were backed by IS central command through funding, propaganda, and received texts from the "al Himmah Library", a collection of IS's Islamic writings. Although both wings remained militarily relatively weak, they were strong enough to hold territory in the remote areas where they were based.[29] By 2020, the Congolese branch appeared to be generally weaker than the Mozambican one. The two wings mostly operated autonomously, and had stronger links to IS central command than to each other.[57] Before the emergence of IS-CAP, Mozambican and Congolese Islamists were known to have had occasional contacts.[34] IS-Central designated its Somali branch as "command center" for both IS-CAP wings.[57] In general, however, researchers found no evidence that the central command held significant control over IS-CAP's branches.[34]

Since May 2022, the Congolese and Mozambican branches were recognized by IS central command as autonomous units within its network.[50] IS-Central officially separated the Mozambican wing from IS-CAP, naming it the "Mozambican Province".[51][58] The Congolese and Mozambican IS forces continued to maintain links after this split, but also began to "feud" with each other over the distribution of money and communications hierarchies within the IS global network.[58]

Congolese wing

[edit]The Congolese IS-CAP branch is mostly limited to parts of eastern Congo,[42] and has claimed that its attacks in Uganda are organized by "a security detachment".[44] Ethnically, the Congolese branch is dominated by Ugandans, followed by Congolese, many of whom were forcibly recruited.[42] The group has also members from Tanzania, Kenya, Burundi,[59] and at least one from Jordan.[59][47] The Congolese branch finances itself with illegal gold mining.[59]

IS-CAP's Congolese branch has been led by Musa Baluku, an ADF veteran commander, since its foundation.[34][60] Zakaria Banza Souleymane (better known as "Bongela Chuma") served as Baluku's deputy by 2022.[47] Ahmad Mahmood Hassan (alias "Abuwakas") is another high-ranking IS-CAP commander who had previously served in the ADF. Abuwakas, a Tanzanian national of Arab descent, has been regarded as the head of an IS-CAP camp, bomb production, "online outreach", and the one mainly responsible for coordination between IS-Central and IS-CAP.[46] Several other commanders of the Congolese branch were captured in late 2021 and early 2022, including Salim Mohammed (a Kenyan), Benjamin Kisokeranio, and Cheikh Banza Mudjaribu Zakaria Abah Adore (Bongela Chuma's brother).[47]

Mozambican wing (until 2022)

[edit]The IS wing of Mozambique, also called "Islamic State in Mozambique",[50] was mainly composed of Mozambicans and a smaller number of foreign volunteers from Tanzania and the Comoros. The group consisted of about 600 to 1,200 militants by early 2022.[59] By 2021, IS-CAP was reportedly led by Abu Yasir Hassan, a Tanzanian, in Cabo Delgado.[34][60] In addition, Bonomade Machude Omar (alias "Ibn Omar") was identified as "senior commander and lead coordinator for all attacks" of IS-CAP in Mozambique by the United States Department of State.[40]

The Mozambican IS forces received "financial and material support" from South Africans, and at least two South African nationals had probably joined the Cabo Delgado insurgency by late 2020.[61] In addition, the conquest of Mocímboa da Praia provided IS-CAP with steady revenue, as the group was able to tax the local trade in minerals and drugs; at the time, the city served as a major hub for narcotics smuggling.[62]

Policies

[edit]Though maintaining locally developed characteristics, IS-CAP has generally adopted the ideology of the Islamic State and several policies of IS-Central. For instance, it has embraced the harsh treatment of Christians based on rules outlined by IS-Central, including the jizya tax and various restrictions; Christians who do not comply with these rules are persecuted by IS-CAP.[51] IS-CAP is regarded as the politically most extreme group active in the DR Congo and Uganda, having been blamed for numerous massacres of civilians,[46] especially Christians.[53]

Propaganda

[edit]IS-CAP's Congolese branch produces propaganda videos.[48] Over time, the group began to integrate its media output into the Islamic State's central media apparatus.[63] It first began producing beheading videos in 2021.[64] Its propaganda has also become increasingly localized over the years, with it starting to use Swahili nasheeds instead of Arabic ones since 2022. At the same time, it has gradually begun to copy IS-Central's media style: For instance, IS-CAP integrated "hyper-violence" into its videos. The individuals appearing in its media also began to dress in black kanzus which are similar to the clothing often worn by IS members in other parts of the world. Researchers Caleb Weiss and Ryan O'Farrell stated that IS-CAP is trying to present itself as "regionally-oriented representative of the Islamic State’s global brand".[48]

By 2022, IS-CAP had become important enough to the IS central command that official IS propaganda implored foreign volunteers to venture to the Congo, Mozambique or other African areas instead of the Middle East, as "the land of Africa [...] is today a land of hijra and jihad".[51] However, Operation Shujaa had a major impact on IS-CAP'S propaganda. In 2024, researchers Caleb Weiss and Ryan O'Farrell stated that the group's media had been reduced to a "shadow of its former self" due to the Uganda-Congolese military offensive.[56]

Designation as terrorist organization(s)

[edit]In March 2021, the US State Department designated the branches in the DRC and Mozambique as separate terrorist organisations under the names "ISIS-DRC" and "ISIS-Mozambique".[60][65]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "S/2024/92". United Nations. Retrieved 1 February 2024.

- ^ "Terrorist Organizations". CIA. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ a b West (2019), p. 7.

- ^ Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 25.

- ^ Caleb Weiss (15 October 2017). "Islamic State-loyal group calls for people to join the jihad in the Congo". Long War Journal. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ West (2019), pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Candland et al. 2022, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d Robert Postings (30 April 2019). "Islamic State recognizes new Central Africa Province, deepening ties with DR Congo militants". Defense Post. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b c Robert Postings (13 June 2019). "Islamic State arrival in Mozambique further complicates Cabo Delgado violence". Defense Post. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "AU confirms ISIS infiltration in East Africa". The Independent (Uganda). 24 May 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Bridget Johnson (18 April 2018). "Mozambique: Police Deny Alleged Terrorist Infiltration". AllAfrica. Archived from the original on 24 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "Monitor: IS claims to have set up its own Africa province". AP. 18 April 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ West (2019), p. 9.

- ^ "IS Down But Still a Threat in Many Countries". Voice of America. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Candland et al. 2021, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Caleb Weiss (4 June 2019). "Islamic State claims first attack in Mozambique". Long War Journal. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ Sirwan Kajjo; Salem Solomon (7 June 2019). "Is IS Gaining Foothold in Mozambique?". Voice of America. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ Sauer, Pjotr (31 October 2019). "7 Kremlin-Linked Mercenaries Killed in Mozambique in October — Sources". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Lazarides (2019), p. 5.

- ^ Lazarides (2019), pp. 5–6.

- ^ "The Islamic State's Bayat Campaign". jihadology.net. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ "Mozambique admits presence of Islamic State fighters for first time". the South African. 25 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Insurgents Kill 8 Gas Project Workers in Northern Mozambique". Defense Post. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (3 July 2020). "Islamic State Editorial on Mozambique". Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Questions about SANDF deployment in Mozambique unanswered". news24. 9 July 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Caleb Weiss (1 July 2020). "ISCAP Ambushes UN Peacekeepers in the DRC, Exploits Coronavirus". Long War Journal. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Mocimboa da Praia: Key Mozambique port 'seized by IS'". BBC. 12 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "ISIS take over luxury islands popular among A-list celebrities". News.com.au. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ a b Jacob Zenn (26 May 2020). "ISIS in Africa: The Caliphate's Next Frontier". Center for Global Policy. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Candland et al. 2021, p. 2.

- ^ Candland et al. 2021, p. 13.

- ^ Candland et al. 2021, pp. 17–18, 24–25.

- ^ a b Caleb Weiss; Ryan O'Farrell (23 July 2023). "PULI: Uganda's Other (Short-lived) Jihadi Group". Long War Journal. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Dino Mahtani; Nelleke van de Walle; Piers Pigou; Meron Elias (18 March 2021). "Understanding the New U.S. Terrorism Designations in Africa". Crisis Group. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Ives, Mike; Kwai, Isabella (October 20, 2020). "1,300 Prisoners Escape From Congo Jail After an Attack Claimed by ISIS". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Warner et al. 2020, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Cabo Ligado Weekly: 29 March-4 April" (PDF). Cabo Ligado (ACLED, Zitamar News, Mediafax). 6 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Islamic State group says it's behind Congo suicide bombing". ABC News. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- ^ "Two explosions hit Congo's eastern city of Beni". AP NEWS. 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-30.

- ^ a b "Cabo Ligado Weekly: 2–8 August". Cabo Ligado (ACLED, Zitamar News, Mediafax). 10 August 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ Cabo Delgado: Não existe “Siria 1” e nem “Siria 2” Archived 2022-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, 19 August 2021

- ^ a b c Caleb Weiss; Ryan O'Farrell (9 September 2021). "Analysis: The Islamic State's expansion into Congo's Ituri Province". Long War Journal. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Deadly blast in Ugandan capital a 'terrorist act': President". France24. 24 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Caleb Weiss; Ryan O'Farrell (17 November 2021). "Analysis: Islamic State targets Uganda with bombings". Long War Journal. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ United Nations 2022, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Zenn 2023c.

- ^ a b c d Zenn 2022.

- ^ a b c Caleb Weiss; Ryan O'Farrell (6 April 2022). "ADF renews pledge of allegiance to new Islamic State leader". Long War Journal. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Candland et al. 2022, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Kate Chesnutt; Katherine Zimmerman (8 September 2022). "The State of al Qaeda and ISIS Around the World". Critical Threats. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (6 June 2023). "The Islamic State In Sub-Saharan Africa: The New "Remaining And Expanding"". Hoover Institute. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ ACN (2022-10-24). "Nun murdered in attack in DR Congo". ACN International. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ a b Zenn 2023a.

- ^ "Uganda: 25 killed by militants in school attack". BBC News. 17 June 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ^ "Parents submit DNA samples to ID Uganda school massacre victims". Al Jazeera. 20 June 2023. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ a b Weiss & O'Farrell 2024, p. 19.

- ^ a b Warner et al. 2020, p. 26.

- ^ a b Zenn 2023b.

- ^ a b c d United Nations 2022, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Caleb Weiss (11 March 2021). "State Department designates Islamic State in DRC, Mozambique". Long War Journal. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Jokinen 2020, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Renon, Eva (5 April 2021). "Terrorism in Mozambique's Cabo Delgado province: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming years". IHS Markit. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Candland et al. 2022, p. 42.

- ^ Candland et al. 2022, p. 45.

- ^ "State Department Terrorist Designations of ISIS Affiliates and Senior Leaders". US Department of State. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

Works cited

[edit]- Candland, Tara; Finck, Adam; Ingram, Haroro J.; Poole, Laren; Vidino, Lorenzo; Weiss, Caleb (March 2021). "The Islamic State in Congo" (PDF). George Washington University.

- Candland, Tara; O'Farrell, Ryan; Poole, Laren; Weiss, Caleb (June 2022). Cruickshank, Paul; Hummel, Kristina (eds.). "The Rising Threat to Central Africa: The 2021 Transformation of the Islamic State's Congolese Branch" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 15 (6). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 38–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2022.

- Warner, Jason; Hulme, Charlotte (2018). "The Islamic State in Africa: Estimating Fighter Numbers in Cells Across the Continent" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 11 (7). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 21–28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- Warner, Jason; O'Farrell, Ryan; Nsaibia, Héni; Cummings, Ryan (2020). "Outlasting the Caliphate: The Evolution of the Islamic State Threat in Africa" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 13 (11). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 18–33.

- West, Sunguta (31 May 2019). "Has Islamic State Really Entered the Congo and is an IS Province There a Gamble?" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. 17 (11). Jamestown Foundation: 7–9.

- Lazarides, Nicholas (6 November 2019). "Islamic State Central Africa Province: Rebranding or Coopting of ADF Faction" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. 17 (21). Jamestown Foundation: 5–6.

- Jokinen, Christian (5 November 2020). "Islamic State's South African Fighters in Mozambique: The Thulsie Twins Case" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. 18 (20). Jamestown Foundation: 6–7.

- "Twenty-ninth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2368 (2017) concerning ISIL (Da'esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities" (PDF). United Nations. February 2022.

- Weiss, Caleb; O'Farrell, Ryan (2024). "Media Matters: How Operation Shujaa Degraded the Islamic State's Congolese Propaganda Output" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. 17 (3). West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center: 19–21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- Zenn, Jacob (February 2022). "Operation Shujaa Targets Islamic State's Leadership in Congo with Arrests of Salim Mohammed, Benjamin Kisokeranio, and Cheikh Banza". Militant Leadership Monitor. 13 (1). Jamestown Foundation.

- Zenn, Jacob (July 2023). "Brief: Islamic State Highlights Killings and Claimed Attacks in the Congo and Mozambique". Terrorism Monitor. 21 (15). Jamestown Foundation.

- Zenn, Jacob (August 2023). "Abubakar Mainok: ISWAP's Sahel-Based al-Furqan Representative". Militant Leadership Monitor. 14 (7). Jamestown Foundation.

- Zenn, Jacob (September 2023). "Abuwakas: The Arab–Tanzanian Face of Islamic State's Jihad in the Congo". Militant Leadership Monitor. 14 (8). Jamestown Foundation.

- Factions of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

- Guerrilla organizations

- Jihadist groups

- Insurgency in Cabo Delgado

- Allied Democratic Forces

- Rebel groups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Organizations designated as terrorist by the United States

- Terrorism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Terrorism in Mozambique

- Terrorism in Uganda