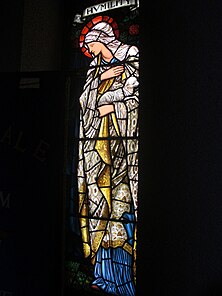

Humility

Humility is the quality of being humble.[1] Dictionary definitions describe humility as low self-regard and a sense of unworthiness.[2] In a religious context, humility can mean a recognition of self in relation to a deity (i.e. God), and subsequent submission to that deity as a member of that religion.[3][4] Outside of a religious context, humility is defined as being "unselved"—liberated from consciousness of self—a form of temperance that is neither having pride (or haughtiness) nor indulging in self-deprecation.[5]

Humility refers to a proper sense of self-regard. In contrast, humiliation involves the external imposition of shame on a person. Humility may be misappropriated as ability to suffer humiliation through self-denigration. This misconception arises from the confusion of humility with traits like submissiveness and meekness. Such misinterpretations prioritize self-preservation and self-aggrandizement over true humility, which emphasizes a diminished emphasis on the self.[6]

In many religious and philosophical traditions, humility is regarded as a virtue that prioritizes social harmony. It strikes a balance between two sets of qualities. This equilibrium lies in having a reduced focus on oneself, which leads to lower self-importance and diminished arrogance, while also possessing the ability to demonstrate strength, assertiveness, and courage. This virtue is exhibited in the pursuit of upholding social harmony, recognizing our human dependence on it. It contrasts with maliciousness, hubris, and other negative forms of pride, and is an idealistic and rare intrinsic construct that has an extrinsic side.

Term

[edit]The term "humility" comes from the Latin word humilitas, a noun related to the adjective humilis, which may be translated as "humble", but also as "grounded", or "from the earth", since it derives from humus (earth). See the English humus.[7]

The word "humble" may be related to feudal England where the least-valuable cuts of meat, or "umbles"[8] (whatever was left over when the upper classes had taken their parts), were provided to the lowest class of citizen.

Mythology

[edit]Aidos, in Greek mythology, was the daimona (goddess) of shyness, shame, and humility.[9] She was the quality that restrained human beings from wrong.

Religious views of humility

[edit]Abrahamic

[edit]Judaism

[edit]

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks states that in Judaism humility is an appreciation of oneself, one's talents, skills, and virtues. It is not meekness or self-deprecating thought, but the effacing of oneself to something higher. Humility is not to think lowly of oneself, but to appreciate the self one is.[10] In recognition of the mysteries and complexities of life, one becomes humbled to the vastness of what one is and what one can achieve.[11]

Rabbi Pini Dunner discusses that humility is to place others first; it is to appreciate others' worth as important. In recognizing our worth as people, Rabbi Dunner shows that looking into the zillions of stars in the sky, and in the length and history of time, you and I are insignificant, like dust. Rabbi Dunner states that Moses wrote in the Torah, "And Moses was exceedingly humble, more than any man on the face of the earth"(Numbers 12:3). How is it possible to be humble and write you are the most humble? The conclusion is that Moses knew he was humble. It is not in denial of your talents and gifts but to recognize them and live up to your worth and something greater. It is in the service to others that is the greatest form of humility.[citation needed]

Amongst the benefits of humility described in the Hebrew Bible, that is shared by many faiths, are honor, wisdom, prosperity, the protection of the Lord, and peace. In addition, "God opposes the proud but gives grace to the humble" (Proverbs 3:34) is another phrase in the Hebrew Bible that values humility and humbleness.

Christianity

[edit]Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others. In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus: Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage; rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death— even death on a cross!

New Testament exhortations to humility are found in many places, for example "Blessed are the meek" (Matthew 5:5), "He who exalts himself will be humbled and he who humbles himself will be exalted" (Matthew 23:12), as well as (Philippians 2:1–17) and throughout the Book of James. Also Jesus Christ's behavior in general, and submission to unjust torture and execution in particular, are held up as examples of righteous humility: "Who, when he was reviled, did not revile: when he suffered, he threatened not: but delivered himself to him that judged him justly" (1 Peter 2:23).[4]

C. S. Lewis writes, in Mere Christianity, that pride is the "anti-God" state, the position in which the ego and the self are directly opposed to God: "Unchastity, anger, greed, drunkenness, and all that, are mere fleabites in comparison: it was through Pride that the devil became the devil: Pride leads to every other vice: it is the complete anti-God state of mind."[12] In contrast, Lewis contends that in Christian moral teaching the opposite of pride is humility. This is popularly illustrated by a phrase wrongly attributed to Lewis, "Humility is not thinking less of yourself, but thinking of yourself less." This is an apparent paraphrase, by Rick Warren in The Purpose Driven Life, of a passage found in Mere Christianity: Lewis writes, regarding the truly humble man,

Do not imagine that if you meet a really humble man he will be what most people call "humble" nowadays: he will not be a sort of greasy, smarmy person, who is always telling you that, of course, he is nobody. Probably all you will think about him is that he seemed a cheerful, intelligent chap who took a real interest in what you said to him. If you do dislike him it will be because you feel a little envious of anyone who seems to enjoy life so easily. He will not be thinking about humility: he will not be thinking about himself at all.

St. Augustine stresses the importance of humility in the study of the Bible, with the exemplars of a barbarian Christian slave, the apostle Paul, and the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8.[13]: prooem. 4–7 Both learner and teacher need to be humble, because they learn and teach what ultimately belongs to God.[13]: prooem. 7–8 [14] Humility is a basic disposition of the interpreter of the Bible. The confidence of the exegete and preacher arises from the conviction that his or her mind depends on God absolutely.[13]: I.1.1 Augustine argues that the interpreter of the Bible should proceed with humility, because only a humble person can grasp the truth of Scripture.[13]: II.41.62 [15]

One with humility is said to be a fit recipient of grace; according to the words of St. James, "God opposes the proud but gives grace to the humble" (Proverbs 3:34, 1 Peter 5:5, James 4:6).

"True humility" differs from "false humility" which consists of deprecating one's own sanctity, gifts, talents, and accomplishments for the sake of receiving praise or adulation from others. That sort is personified by the fictional character Uriah Heep created by Charles Dickens. In this context legitimate humility comprises the following behaviors and attitudes:

- submitting to God and legitimate authority

- recognizing virtues and talents that others possess, particularly those that surpass one's own, and giving due honor and, when required, obedience

- recognizing the limits of one's talents, ability, or authority

The vices opposed to humility are:

- Pride

- Too great obsequiousness or abjection of oneself; this would be considered an excess of humility, and could easily be derogatory to one's office or holy character; or it might serve only to pamper pride in others, by unworthy flattery, which would occasion their sins of tyranny, arbitrariness, and arrogance. The virtue of humility may not be practiced in any external way that would occasion vices in others.[16]

Catholicism

[edit]

Catholic texts view humility as annexed to the cardinal virtue of temperance.[3][16] It is viewed as a potential part of temperance because temperance includes all those virtues that restrain or express the inordinate movements of our desires or appetites.[16]

St. Bernard defines it as, "A virtue by which a man knowing himself as he truly is, abases himself. Jesus Christ is the ultimate definition of Humility."[16]

Humility was a virtue extolled by Saint Francis of Assisi, and this form of Franciscan piety led to the artistic development of the Madonna of humility first used by them for contemplation.[18] The Virgin of humility sits on the ground, or upon a low cushion, unlike the Enthroned Madonna representations.[19] This style of painting spread quickly through Italy and by 1375 examples began to appear in Spain, France, and Germany and it became the most popular among the styles of the early Trecento artistic period.[20]

St. Thomas Aquinas, a 13th-century philosopher and theologian in the Scholastic tradition, says "the virtue of humility... consists in keeping oneself within one's own bounds, not reaching out to things above one, but submitting to one's superior".[21]

Islam

[edit]In the Qur'an, various Arabic words conveying the meaning of "humility" are used. The very term "Islam" can be interpreted as "surrender (to God), humility", from the triconsonantal root S-L-M; other words used are tawadu and khoshou:

And the servants of (Allah) Most Gracious are those who walk on the earth in humility, and when the ignorant address them, they say, "Peace!"

"The loftiest in status are those who do not know their own status, and the most virtuous of them are those who do not know their own virtue."

— Imam ash-Shafi'i [22]

"Your humbleness humbles others and your modesty brings out the modesty of others."

— Abdulbary Yahya

Successful indeed are the believers: those who humble themselves in prayer;

— Quran 23:1-2

Eastern

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]Buddhism is a religion of "self"-examination.[23] The natural aim of the Buddhist life is the state of enlightenment, gradually cultivated through meditation and other spiritual practices. Humility, in this context, is a characteristic that is both an essential part of the spiritual practice, and a result of it.[23]: 180, 183 As a quality to be developed, it is deeply connected with the practice of Four Abodes (Brahmavihara): love-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity.[citation needed] As a result of the practice, this cultivated humility is expanded by the wisdom acquired by the experience of ultimate emptiness (śūnyatā) and non-self (anatta).[23]: 181 Humility, compassion, and wisdom are intrinsic parts of the state of enlightenment.[citation needed] On the other hand, not being humble is an obstacle on the path of enlightenment which needs to be overcome.[23]: 180 In the Tipitaka (the Buddhist scriptures), criticizing others and praising oneself is considered a vice; but criticizing oneself and praising others is considered a virtue.[23]: 178 Attachment to the self, apart from being a vice in itself, also leads to other evil states that create suffering.[23]: 182

In the Tipitaka, in the widely known Mangala Sutta, humility (nivato, literally: "without air") is mentioned as one of the thirty-eight blessings in life.[24] In the Pāli Canon, examples of humility include the monk Sariputta Thera, a leading disciple of the Buddha, and Hatthaka, a leading lay disciple. In later Pali texts and Commentaries, Sariputta Thera is depicted as a forgiving person, who is quick to apologize and accepting of criticism. In the suttas (discourses of the Buddha) Hatthaka was praised by the Buddha when he was unwilling to let other people know his good qualities.[25]

Once, the Buddha mentioned to some monks that his lay disciple Hatthaka had seven wonderful and marvellous qualities; these being faith, virtue, propriety, self-respect, learning, generosity and wisdom. Later, when Hatthaka learned how the Buddha had praised him he commented: 'I hope there were no laypeople around at the time'. When this comment was reported back to the Buddha, he remarked: "Good! Very good! He is genuinely modest and does not want his good qualities to be known to others. So you can truly say that Hatthaka is adorned with this eighth wonderful and marvellous quality 'modesty'." (A.IV,218)[clarification needed][26]

In Buddhist practice, humility is practiced in a variety of ways. Japanese Soto Zen monks bow and chant in honor of their robes before they don them. This serves to remind them of the connection of the monk's robes with enlightenment. Buddhist monks in all traditions are dependent on the generosity of laypeople, through whom they receive their necessities. This in itself is a practice of humility.[23]: 178 [27]

Hinduism

[edit]In Sanskrit literature, the virtue of humility is explained with many terms, some of which use the root word, नति (neti).[28] Sanskrit: नति comes from Sanskrit: न ति, lit. 'No "Me" / I am not'. Related words include विनति (viniti), संनति (samniti, humility towards), and the concept amanitvam, listed as the first virtue in the Bhagavad Gita.[29] Amanitvam is a fusion word for "pridelessness" and the virtue of "humility".[30] Another related concept is namrata (नम्रता), which means modest and humble behavior.

Different scholars have varying interpretations of amanitvam, humility, as a virtue in the Bhagavad Gita.[31] For example, Prabhupada explains humility to mean one should not be anxious to have the satisfaction of being honored by others.[32] The material conception of life makes us very eager to receive honor from others, but from the point of view of a man in perfect knowledge—who knows that he is not this body—anything—honor or dishonor—pertaining to this body is useless.

Tanya Jopson explains amanitvam, humility, as lack of arrogance and pride, and one of twenty-six virtues in a human being that if perfected, leads one to a divine state of living and the ultimate truth.[33]

Eknath Easwaran writes that the Gita's subject is "the war within, the struggle for self-mastery that every human being must wage if he or she is to emerge from life victorious",[34] and "The language of battle is often found in the scriptures, for it conveys the strenuous, long, drawn-out campaign we must wage to free ourselves from the tyranny of the ego, the cause of all our suffering and sorrow".[35] To get in touch with your true self, whether you call that God, Brahman, etc., you have to let go of the ego. The Sanskrit word Ahamkara literally translates into The-sound-of-I, or quite simply the sense of the self or ego.

Mahatma Gandhi interprets the concept of humility in Hinduism much more broadly, where humility is an essential virtue that must exist in a person for other virtues to emerge. To Mahatma Gandhi, Truth can be cultivated, as well as Love, but Humility cannot be cultivated. Humility has to be one of the starting points. He states, "Humility cannot be an observance by itself. For it does not lend itself to being practiced. It is however an indispensable test of ahimsa (non-violence)." Humility must not be confused with mere manners; a man may prostrate himself before another, but if his heart is full of bitterness for the other, it is not humility. Sincere humility is how one feels inside, it's a state of mind. A humble person is not himself conscious of his humility, says Gandhi.[36]

Swami Vivekananda, a 19th century scholar of Hinduism, argues that the concept of humility does not mean "crawling on all fours and calling oneself a sinner". In Vivekananda's Hinduism, each human being the Universal, recognizing and feeling oneness with everyone and everything else in the universe, without inferiority or superiority or any other bias, is the mark of humility.[37] To Dr. S Radhakrishnan, humility in Hinduism is the non-judgmental state of mind when we are best able to learn, contemplate and understand everyone and everything else.[38]

Sikhism

[edit]

- Make contentment your ear-rings, humility your begging bowl, and meditation the ashes you apply to your body.

- Listening and believing with love and humility in your mind.

- In the realm of humility, the Word is Beauty.

- Modesty, humility and intuitive understanding are my mother-in-law and father-in-law.

Sayings of Guru Granth Sahib, Guru Nanak, First Guru Of Sikhism[citation needed]

Neecha Andar Neech Jaat Neechi Hu At Neech Nanak Tin Kai Sang Saath Vadian Sio Kia Rees. |

Nanak is the companion of the lowest of the low and of the condemned lot. He has nothing in common with the high born |

| —Sri Guru Granth Sahib[citation needed] |

Baba Nand Singh Ji Maharaj said about Guru Nanak that Garibi, Nimrata, Humility is the Divine Flavour, the most wonderful fragrance of the Lotus Feet of Lord Guru Nanak.[39] There is no place for Ego (referred to in Sikhism as Haumain) in the sphere of Divine Love, in the sphere of true Prema Bhagti. That is why in the House of Guru Nanak one finds Garibi, Nimrata, Humility reigning supreme. Guru Nanak was an Incarnation of Divine Love and a Prophet of True Humility.[fact or opinion?]

According to Sikhism all people, equally, have to bow before God so there ought to be no hierarchies among or between people. According to Nanak the supreme purpose of human life is to reconnect with Akal (The Timeless One), however, egotism is the biggest barrier in doing this. Using the guru's teaching remembrance of nām (the divine Word)[40] leads to the end of egotism. The immediate fruit of humility is intuitive peace and pleasure. With humility they[clarification needed] continue to meditate on the Lord, the treasure of excellence. The God-conscious being is steeped in humility. One whose heart is mercifully blessed with abiding humility.[sentence fragment] Sikhism treats humility as a begging bowl before the god.

Sikhs extend this belief in equality, and thus humility, towards all faith: "all religious traditions are equally valid and capable of enlightening their followers".[41] In addition to sharing with others Guru Nanak inspired people to earn an honest living without exploitation and also to remember the divine name (God). Guru Nanak described living an "active, creative, and practical life" of "truthfulness, fidelity, self-control, and purity" as being higher than a purely contemplative life.[relevant?][42]

Baba Nand Singh Sahib is renowned as the most humble Sikh Saint in the history of Sikhism. One time the disciples of Baba Harnam Singh Ji, the spiritual preceptor of Baba Nand Singh Ji Maharaj asked him how much power He had transmitted to Baba Nand Singh Ji Maharaj to which he replied:[43]

"Rikhi Nand Singh holds in His hand Infinite Divine Powers. By just opening His fist He can create as many such-like universes as He likes and by closing the same fist can withdraw all those universes unto Himself.

"But the whole beauty is that being the supreme Repository of all the Infinite Divine Powers, He claims to be nothing and is so humble."

— Baba Harnam Singh Ji Maharaj

He who is the Highest is the Lowest. Highest in the Lowest is the Real Highest.

— Baba Narinder Singh Ji

Meher Baba

[edit]The spiritual teacher Meher Baba held that humility is one of the foundations of devotional life: "Upon the altar of humility we must offer our prayers to God."[44] Baba also described the power of humility to overcome hostility: "True humility is strength, not weakness. It disarms antagonism and ultimately conquers it."[45] Finally, Baba emphasized the importance of being humble when serving others: "One of the most difficult things to learn is to render service without bossing, without making a fuss about it and without any consciousness of high and low. In the world of spirituality, humility counts at least as much as utility."[46]

Taoism

[edit]Here are my three treasures.

Guard and keep them!

The first is pity; the second, frugality; the third, refusal to be "foremost of all things under heaven".

For only he that pities is truly able to be brave;

Only he that is frugal is able to be profuse.

Only he that refuses to be foremost of all things

Is truly able to become chief of all Ministers.

At present your bravery is not based on pity, nor your profusion on frugality, nor your vanguard on your rear; and this is death.

Humility, in Taoism, is defined as a refusal to assert authority or a refusal to be first in anything. The act of daring, in itself, is a refusal of wisdom and a rush to enjoin circumstances before you are ready. Along with compassion and frugality, humility is one of the three treasures (virtues) in the possession of those who follow the Tao.[48]

The treasure of humility, in Chinese is a six-character phrase instead of a single word: Chinese: 不敢為天下先; pinyin: Bugan wei tianxia xian "not dare to be first/ahead in the world".[48] Ellen Chen notes[49] that:

The third treasure, daring not be at the world's front, is the Taoist way to avoid premature death. To be at the world's front is to expose oneself, to render oneself vulnerable to the world's destructive forces, while to remain behind and to be humble is to allow oneself time to fully ripen and bear fruit. This is a treasure whose secret spring is the fear of losing one's life before one's time. This fear of death, out of a love for life, is indeed the key to Taoist wisdom.[49]

Furthermore, also according to the Tao Te Ching a wise person acts without claiming the results as his. He achieves his merit and does not rest (arrogantly) in it. He does not wish to display his superiority.[48]: 77.4

Wicca

[edit]In the numerous traditions of initiatory Wicca, called in the U.S.A. "British Traditional Wicca", four paired & balanced qualities are recommended in liturgical texts as having come from the Wiccan Goddess:

...let there be beauty and strength, power and compassion, honor and humility, mirth and reverence within you.

— Doreen Valiente, The Charge of the Goddess, prose version

In the matter of humility, this deific instruction appropriately pairs being honorable with being humble. Characteristically, this Wiccan "virtue" is balanced by its partner virtue.

Philosophical views of humility

[edit]

Kant's view of humility has been defined as "that meta-attitude that constitutes the moral agent's proper perspective on himself as a dependent and corrupt but capable and dignified rational agent".[50] Kant's notion of humility relies on the centrality of truth and rational thought leading to proper perspective and his notion can therefore be seen[by whom?] as emergent.

Mahatma Gandhi said that an attempt to sustain truth without humility is doomed to become an "arrogant caricature" of truth.[51]

While many religions and philosophers view humility as a virtue, some have been critical of it, seeing it as opposed to individualism.

"No doubt, when modesty was made a virtue, it was a very advantageous thing for the fools," wrote Arthur Schopenhauer, "for everybody is expected to speak of himself as if he were one".[52]

Nietzsche viewed humility as a strategy used by the weak to avoid being destroyed by the strong. In Twilight of the Idols he wrote: "When stepped on, a worm doubles up. That is clever. In that way he lessens the probability of being stepped on again. In the language of morality: humility."[53] He believed that his idealized Übermensch would be more apt to roam unfettered by pretensions of humility, proud of his stature and power, but not reveling idly in it, and certainly not displaying hubris.[citation needed] But, if so, this would mean the pretension aspect of this kind of humility is more akin to obsequiousness and to other kinds of pretentious humility.

Humility and leadership

[edit]Research suggests that humility is a quality of certain types of leaders and is studied as a trait that can enhance leadership effectiveness. For example, Jim Collins and his colleagues found that a certain type of leader, whom they term "level 5", possesses humility and fierce resolve.[54] The research suggests that humility is multi-dimensional and includes self-understanding and awareness, openness, and perspective taking.[55]

See also

[edit]- Aidos – Theme in Ancient Greek literature

- Cultural humility

- Epistemic humility – Philosophical view of scientific observation

- Humiliation – Abasement of pride

- Humility theology – American philanthropic organization

- Intellectual humility – Recognition of the limits of your knowledge and awareness of your fallibility

- Madonna of humility – Artistic subject

- Moral character – Steady moral qualities in people

- Pharisee and the Publican – Parable taught by Jesus of Nazareth according to the Christian Gospel of Luke

References

[edit]- ^

The dictionary definition of humble at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of humble at Wiktionary

- ^ Snyder, C.R.; Lopez, Shane J. (2001). Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-19-803094-2.

- ^ a b Herbermann; et al., eds. (1910). "Humility". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. pp. 543–544.

- ^ a b Herzog; et al., eds. (1860). "Humility". The Protestant theological and ecclesiastical encyclopedia. Vol. 2. pp. 598–599.

- ^

- Peterson, Christopher (2004). Character strengths and virtues a handbook and classification. Washington, DC New York: American Psychological Association Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516701-6.

- Worthington, Everett L. Jr. (2007). Handbook of Forgiveness. Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-135-41095-7.

- ^

- Schwarzer, Ralf (2012). Personality, human development, and culture: international perspectives on psychological science. Hove: Psychology. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-0-415-65080-9.

- Jeff Greenberg; Sander L. Koole; Tom Pyszczynski (2013). Handbook of Experimental Existential Psychology. Guilford Publications. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-4625-1479-3.

- ^ "humble". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 15 August 2023.

- ^ Sykes, Naomi (Summer 2010). "1066 and all that" (PDF). Deer. 15 (6). British Deer Society: 20–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-09. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ Scheff, Thomas; Retzinger, Suzanne (2001). Emotions and Violence: shame and rage in destructive conflicts. iUniverse. p. 7. ISBN 0-595-21190-9.

- ^

- Sacks, Jonathan. "Greatness is Humility". Chabad.org.

- Sacks, Jonathan. "On Humility". Chabad.org.

- ^

- Moss, Aaron. "What is Humility?". Chabad.org.

- Citron, Aryeh. "Humility - Parshat Vayikra". www.chabad.org.

- ^ C. S. Lewis (6 February 2001). Mere Christianity. ISBN 978-0-06-065292-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Augustine of Hippo (397). De Doctrina Christiana.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 4:7

- ^ Woo, B. Hoon (2013). "Augustine's Hermeneutics and Homiletics in De doctrina christiana". Journal of Christian Philosophy. 17: 99–103.

- ^ a b c d Devine, Arthur. "Humility". Catholic Encyclopedia. newadvent.org.

- ^ Camiz, Franca Trinchieri; McIver, Katherine A. (2003). Art and music in the early modern period. Ashgate. p. 15. ISBN 0-7546-0689-9.

- ^

- Hall, James (1983). A history of ideas and images in Italian art. Harper & Row. p. 223. ISBN 0-06-433317-5.

- Schiller, Gertrud (1971). Iconography of Christian Art. Vol. 1. Arnoldo Mondadori. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8212-0365-1.

- ^ Earls, Irene (1987). Renaissance Art: A Topical Dictionary. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 174. ISBN 0-313-24658-0.

- ^ Meiss, Millard (1979). Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death. Princeton University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0-691-00312-2.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Contra Gentiles. Translated by Rickaby, Joseph. IV.lv.

- ^ Al-Dhahabī. Siyar A'lam al-Nubala.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tachibana, Shundō (1992). The ethics of Buddhism. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0230-X.

- ^ The Minor Readings and The Illustrator of Ultimate Meaning. Translated by Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu. London: Pali Text Society. 1960.

- ^ Malalasekera, G.P. (2007) [1937]. Dictionary of Pāli proper names. Vol. 2 (1st Indian ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-3022-6.

- ^

- "Modesty". Guide to Buddhism A To Z. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "About Hatthaka". Hatthaka Sutta. AN 8:23. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Tanabe, Willa Jane (2004). "Robes and clothing". In Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. New York [u.a.]: Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale. p. 732. ISBN 0-02-865720-9.

- ^

- "Humility". English-Sanskrit Dictionary (in Sanskrit). Germany. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- "नति [nati]". Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary. France.

- ^ "Bhagwad Gita 13.8-12". See transliteration, and two commentaries.

- ^ Sundararajan, K. R.; Mukerji, Bithika, eds. (2003). Hindu spirituality: Postclassical and modern. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 403–405. ISBN 978-81-208-1937-5.

- ^ Gupta, B. (2006). "Bhagavad Gitā as Duty and Virtue Ethics". Journal of Religious Ethics. 34 (3): 373–395. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9795.2006.00274.x.

- ^ A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1968). Bhagavad Gita As It Is.

- ^

- Jopson, Tanya (7 December 2011). Human Energy-Body Awareness: How Our Energy Body & Vibrational Frequency Create Our Everyday Life. Tanya Jopson. ISBN 978-1-4663-3341-3.

see Divine Qualities under Glossary

- Bhawuk, D.P. (2011). "Epistemology and Ontology of Indian Psychology". Spirituality and Indian Psychology. New York: Springer. pp. 163–184.

- Jopson, Tanya (7 December 2011). Human Energy-Body Awareness: How Our Energy Body & Vibrational Frequency Create Our Everyday Life. Tanya Jopson. ISBN 978-1-4663-3341-3.

- ^ Easwaran, Eknath (2007). The Bhagavad Gita. Translated by Easwaran, Eknath. Nilgiri Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-58638-019-9.

- ^ Easwaran, Eknath (1993). The End of Sorrow: The Bahagavad Gita for Daily Living. Vol. 1. Nilgiri Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-915132-17-1.

- ^

- Mahatma Gandhi. "Humility". The Gita and Satyagraha: The Philosophy of Non-violence and The Doctrine of the Sword.

- Hall, Stephen S. (2010). Wisdom. Alfred A. Knopf. Chapter 8. ISBN 978-0-307-26910-2.

- ^ Swami Vivekananda (1915). The Complete Works of the Swami Vivekananda. Vol. 1. p. 343.

- ^ Radhakrishnan, S.; Muirhead, J.H. (1936). Contemporary Indian Philosophy. London: Allen & Sons.

- ^ "Fragrance of The Holy Feet of Guru Nanak". Rosary of Divine Wisdom. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- ^ McLean, George (2008). Paths to The Divine: Ancient and Indian: 12. Council for Research in Values &. p. 599. ISBN 978-1-56518-248-6.

- ^ Singh Kalsi, Sewa (2007). Sikhism. London: Bravo Ltd. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-85733-436-4.

- ^ Marwha, Sonali Bhatt (2006). Colors of Truth, Religion Self and Emotions. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. p. 205. ISBN 81-8069-268-X.

- ^ "Repository of Infinite Divine Powers". babanandsinghsahib.org. Retrieved 2017-01-01.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses. Vol. 3. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-880619-09-4.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1957). Life at Its Best. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-525-47434-0.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1933). The Sayings of Shri Meher Baba. London: The Circle Editorial Committee. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Lao Tzu (1958). 道德經 [Tao Te Ching]. Translated by Waley, Arthur. p. 225.

- ^ a b c Lao Tzu (1997). English, Jane (ed.). 道德經 [Tao Te Ching]. Translated by Feng, Gia-Fu. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-77619-2.

- ^ a b Lao Tzu (1989). Chen, Ellen M. (ed.). The Te Tao Ching: A New Translation with Commentary. Paragon House. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-679-77619-2.

- ^ Frierson, Patrick. "Kant and the Ethics of Humility (review)". University of Notre Dame. Archived from the original on 2016-05-19.

- ^ "True Celibacy". Young India. 25 June 1925. Archived from the original on 2006-06-30.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1851). "Pride". The Wisdom of Life (Essays). section 2.

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1997). Twighlight of the Idols (PDF). Translated by Polt, Richard (Adobe PDF ebook ed.). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-60384-880-0. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Collins, J. (2001). "Level 5 leadership: The triumph of humility and fierce resolve" (PDF). Harvard Business Review. 79 (1): 66–76. PMID 11189464. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^

- Morris, J.A.; Brotheridge, C.M.; Urbanski, J.C. (2005). "Bringing humility to leadership: Antecedents and consequences of leader humility". Human Relations. 58 (10): 1323–1350. doi:10.1177/0018726705059929. S2CID 146587365.

- Nielsen, R.; Marrone, J.A.; Slay, H.S. (2010). "A new look at humility: Exploring the humility concept and its role in socialized charismatic leadership". Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 17: 33–43. doi:10.1177/1548051809350892. S2CID 145244665.

- Lopez, Shane, ed. (2009). "Humility". The encyclopedia of positive psychology. Vol. 1. Wiler-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-6125-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Murray, Andrew (2014). Humility: The Beauty of Holiness. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5025-5956-2.

External links

[edit]- "Islam's quotes regarding humility". IslamicArtDB.com.

- "Judaism's take on humility". Chabad.org.

- "World scripture: Quotes from religious texts about humility". unification.net.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Humility". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Humility". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.