History of neurology and neurosurgery

The study of neurology and neurosurgery dates back to prehistoric times, but the academic disciplines did not begin until the 16th century. The formal organization of the medical specialties of neurology and neurosurgery are relatively recent, taking place in Europe and the United States only in the 20th century with the establishment of professional societies distinct from internal medicine, psychiatry and general surgery.[1][2] From an observational science they developed a systematic way of approaching the nervous system and possible interventions in neurological disease.

Early history

[edit]Ancient

[edit]

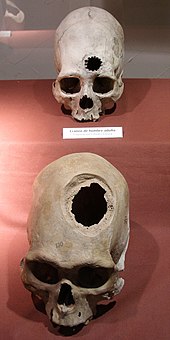

Trepanation, similar to some techniques used today, is the oldest surgical procedure known and was practised in the Stone Age in many parts of the world,[3] and in some areas may have been quite widespread. The main pieces of archaeological evidence are in the forms of cave paintings and human remains. One third of 120 skulls found at a site in France dating to 6500 BCE had undergone trepanning.[4] It was also practised widely in the pre-Columbian Andes.[5][6] These procedures were mostly performed on combatants, with evidence from skeletal remains revealing that the earliest methods usually resulted in death.[6] However, by the 1400s, Incas proved to be "skilled surgeons", as survival rates rose to about 90%, infection rates following the procedure were low and evidence was found showing that some individuals survived the surgery on multiple occasions.[6] Incan surgeons learned to avoid areas of the head that would cause injury, using a scraping method on the skull that would cause less trauma.[6] They also likely used medicinal herbs of the time, such as coca and alcohol for pain while balsam and saponin would be employed for antibiotic purposes.[6]

An ancient Egyptian treatise concerning trauma surgery, the Edwin Smith papyrus, contains descriptions and suggests treatments for various injuries, including some of neurological nature. Specifically, there are descriptions of the meninges, the external surface of the brain, the cerebrospinal fluid and the intracranial pulsations.[7] Not only are these neurological features mentioned, but it is also noticed that some bodily functions can be impaired by brain injuries or injuries to the cervical spine.[7] There are many other examples of observations of neurological phenomena throughout history. The Sumerians illustrated paraplegia caused by physical trauma in a bas relief of a lion with an arrow in its back.[8] Neurological disorders not caused by physical disorder were also investigated. Buddha's physician, Jīvaka Komārabhacca, performed surgery to remove two parasites from a patient's brain in the 5th century BCE.[9]

Slightly later, the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates was convinced that epilepsy has a natural cause, not a sacred one.[10] The ancient Greeks also dissected the nervous system. For example, Aristotle (although he misunderstood the function of the brain) describes the meninges and also distinguishes between the cerebrum and the cerebellum.[11] Slightly later, in Rome, Galen performed many dissections of the nervous system in a variety of species, including the ape. One particular discovery he made was of the importance of the recurrent laryngeal nerves. Originally, he cut through them accidentally while performing an experiment on the nerves that control breathing by vivisection of a strapped-down, squealing pig. The pig immediately stopped squealing, but continued struggling. Galen then performed the same experiment on a variety of animals, including dogs, goats, bears, lions, cows and monkeys, finding similar results each time. Finally, to publicise this new result, Galen demonstrated the experiment on a pair of pigs to a large audience in Rome, telling them: "there is a hairlike pair [of nerves] in the muscles of the larynx on both left and right, which if ligated or cut render the animal speechless without damaging either its life or functional activity".[12]

With surgery, Hua Tuo was an ancient Chinese physician and surgical pioneer who is said to have performed neurosurgical procedures.[13] In Al-Andalus from 936 to 1013 AD, Al-Zahrawi evaluated patients and performed surgical treatments of head injuries, skull fractures, spinal injuries, hydrocephalus, subdural effusions and headache.[14] Concurrently in Persia, Avicenna also presented detailed knowledge about skull fractures and their surgical treatments.[15]

Anatomy and physiology

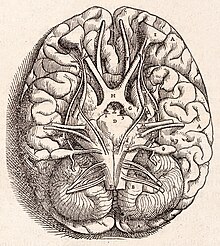

[edit]- Along with most other sciences, the first real advances in neurology and neurosurgery after the Greeks occur in the Renaissance. The invention of the printing press allowed the publication of anatomical textbooks, pages, allowing the dissemination of knowledge. An early example is Johann Peyligk's Compendium philosophiae naturalis, published in Leipzig, Germany in 1499. This work contained 11 woodcuts, depicting the dura mater and pia mater as well as the ventricles.[16]

- A revolution took place in both neurology in particular and in anatomy in general when Andreas Vesalius published his De humani corporis fabrica in 1543. It includes detailed images depicting the ventricles, cranial nerves, pituitary gland, meninges, structures of the eye, the vascular supply to the brain and spinal cord, and an image of the peripheral nerves.[16] Vesalius, unlike many of his contemporaries, did not subscribe to the then common belief that the ventricles were responsible for brain function, arguing that many animals have similar systems of ventricles to those of humans but no true intelligence.[17] It appears that he rarely removed the brain from the skull before cutting it, most of his diagrams showing the brain sitting inside a severed head.[18]

In 1549, Jason Pratensis published De Cerebri Morbis, a volume devoted to neurological diseases, in which he discussed symptoms, as well as ideas from Galen and other Greek, Roman, and Arabic authors.[19] Thomas Willis in 1664 published his Anatomy of the Brain, followed by Cerebral Pathology in 1667. He removed the brain from the cranium and was able to describe it more clearly, setting forth the circle of Willis, the circle of vessels that enables arterial supply of the brain. He had some notions as to brain function, including a vague idea as to localization and reflexes, and described epilepsy, apoplexy, and paralysis. He was among the first few authors to use the word "neurology," after anatomist Jean Riolan the Younger in 1610.[20]

A beginning of the understanding of disease came with the first morbid anatomists, morbid anatomical illustration, and the development of effective colour printing. Matthew Baillie (1761–1823) and Jean Cruveilhier (1791–1874) illustrated the lesions of stroke in 1799 and 1829, respectively.

Bioelectricity and Microscopy

[edit]The famous philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) speculated that every activity of an animal was a necessary reaction to some external stimulus; the connection between the stimulus and the response was made through a definite nervous path. In 1718, Isaac Newton opined in his book Opticks that the brain was sending signals to the muscles through the path of nerves.[21]

Luigi Galvani (1737–1798) demonstrated that electrical stimulation of nerve produced muscle contraction, and the competing work of Charles Bell (1774–1842) and François Magendie (1783–1855) led to the view that the ventral horns of the spinal cord were motor and the dorsal horns sensory. Only when cells were identified microscopically was it possible to progress beyond the crudest anatomical notion. J.E. Purkinje (1787–1869) in 1837 gave the first description of neurones, indeed a very early description of cells of any kind. By 1850, Helmholtz was able to measure the signal conductance speed on a frog's sciatic nerve (about 27 m/s at 20-21 °C).[21][22] Later Golgi and Cajal stained the ramifying branches of nerve cells; these could only touch, or synapse. The brain now had demonstrated form, without localised function. A hemiplegic patient who could not speak led Paul Broca (1824–1880) to the view that functions in the cerebral cortex were anatomically localised. Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) realised as his dogs dribbled that a simple reflex could be modified by higher brain functions. These neurological ideas were coordinated and integrated by the neurophysiologist Charles Scott Sherrington (1857–1952).

Diagnostics

[edit]The first physicians to devote entirely to neurology were Moritz Heinrich Romberg, William A. Hammond, Duchenne de Boulogne, Jean-Martin Charcot and John Hughlings Jackson. Physicians could use the ideas of neurology in practice only if they developed proper tools and procedures for clinical investigation. This happened step by step in the 19th century – tendon hammer, ophthalmoscope, pin and tuning fork, syringe and lumbar puncture. X rays, the electro-encephalography, angiography, myelography and CAT scans were to follow. The clinical neurologists correlated their findings after death with those of the neuropathologist. The best known was W.R. Gowers (1845–1915) who owned a major text in two volumes, of a cerebrospinal tract. By the end of the nineteenth century, the connection was established between stroke and hemiplegia, between trauma and paraplegia, between the spirochaete and the paralysed demency people who filled the mental hospitals. The first chemotherapeutic cure of a serious infection was salvarsan for syphilis, followed by the induction of fever in neurosyphilis. The treatment of neurosyphilis became highly effective when antibiotics were introduced.

Neurosurgery

[edit]Modern

[edit]There was not much advancement in neurosurgery until late 19th early 20th century, when electrodes were placed on the brain and superficial tumors were removed.

Neurosurgery, or the premeditated incision into the head for pain relief, has been around for thousands of years, but notable advancements in neurosurgery have only come within the last hundred years.[23]

History of electrodes in the brain: In 1878 Richard Caton discovered that electrical signals transmitted through an animal's brain. In 1950 Dr. Jose Delgado invented the first electrode that was implanted in an animal's brain, using it to make it run and change direction. In 1972 the cochlear implant, a neurological prosthetic that allowed deaf people to hear was marketed for commercial use. In 1998 researcher Philip Kennedy implanted the first brain–computer interface (BCI) into a human subject.[24]

History of tumor removal: In 1879 after locating it via neurological signs alone, Scottish surgeon William Macewen (1848-1924) performed the first successful brain tumor removal.[25] On 25 November 1884 after English physician Alexander Hughes Bennett (1848-1901) used Macewen's technique to locate it, English surgeon Rickman Godlee (1849-1925) performed the first primary brain tumor removal,[26][27] which differs from Macewen's operation in that Bennett operated on the exposed brain, whereas Macewen operated outside of the "brain proper" via trepanation.[28] Three years later, Victor Horsley (1857–1916) was the first physician to remove a spinal tumour. On 16 March 1907 Austrian surgeon Hermann Schloffer became the first to successfully remove a pituitary tumor.[29] American surgeon Harvey Cushing (1869–1939) successfully removed a pituitary adenoma from an acromegalic in 1909. Treating endocrine hyperfunction by neurosurgery was a major neurological landmark.

Egas Moniz (1874–1955) in Portugal developed a procedure of leucotomy (now mostly known as lobotomy) to treat severe psychiatric disorders. Though it is often said that the development of lobotomy was inspired by the case of Phineas Gage, a railroad worker who had an iron bar driven through his left frontal lobe in 1848, the evidence is against this.[30]

Modern surgical instruments

[edit]The main advancements in neurosurgery came about as a result of highly crafted tools. Modern neurosurgical tools, or instruments, include chisels, curettes, dissectors, distractors, elevators, forceps, hooks, impactors, probes, suction tubes, power tools, and robots.[31][32] Most of these modern tools, like chisels, elevators, forceps, hooks, impactors, and probes, have been in medical practice for a relatively long time. The main difference of these tools, pre and post advancement in neurosurgery, were the precision in which they were crafted. These tools are crafted with edges that are within a millimeter of desired accuracy.[33] Other tools such as hand held power saws and robots have only recently been commonly used inside of a neurological operating room.

See also

[edit]- History of neuraxial anesthesia

- History of neuroscience

- History of neuropsychology

- History of psychology

- History of psychiatry

- History of neurophysiology

- List of neurologists and neurosurgeons

References

[edit]- ^ Koehler, Peter J. (3 July 2018). "The founding of neurology as a specialty: The American situation in context". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 27 (3): 283–291. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2018.1486672. ISSN 0964-704X. PMID 30118412.

- ^ "The Society of Neurological Surgeons: An Historical Perspective". Society of Neurological Surgeons. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ Capasso, Luigi (2002). Principi di storia della patologia umana: corso di storia della medicina per gli studenti della Facoltà di medicina e chirurgia e della Facoltà di scienze infermieristiche (in Italian). Rome: SEU. ISBN 978-88-87753-65-3. OCLC 50485765.

- ^ Restak, Richard (2000). "Fixing the Brain". Mysteries of the Mind. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-0-7922-7941-9. OCLC 43662032.

- ^ Andrushko, Valerie A.; Verano, John W. (September 2008). "Prehistoric trepanation in the Cuzco region of Peru: A view into an ancient Andean practice". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20836. PMID 18386793.

- ^ a b c d e Norris, Scott (12 May 2008). "Inca Skull Surgeons Were "Highly Skilled," Study Finds". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021.

- ^ a b Wilkins, 1964

- ^ Paulissian, 1991 p.35

- ^ Horner, I.B. "Theravāda Vinayapiṭaka Khandhaka (Mahāvagga) 8. Robes (Cīvara) The story of Jīvaka". SuttaCentral. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization, Fact Sheet #168

- ^ von Staden, p.157

- ^ Gross, 1998

- ^ Tubbs, R. Shane; Riech, Sheryl; Verma, Ketan; Chern, Joshua; Mortazavi, Martin; Cohen-Gadol, Aaron A. (1 September 2011). "China's first surgeon: Hua Tuo (c. 108-208 AD)". Child's Nervous System. 27 (9): 1357–1360. doi:10.1007/s00381-011-1423-z. ISSN 1433-0350. PMID 21452005.

- ^ Al-Rodhan, N. R.; Fox, J. L. (1 July 1986). "Al-Zahrawi and Arabian neurosurgery, 936-1013 AD". Surgical Neurology. 26 (1): 92–95. doi:10.1016/0090-3019(86)90070-4. ISSN 0090-3019. PMID 3520907.

- ^ Aciduman, Ahmet; Arda, Berna; Ozaktürk, Fatma G.; Telatar, Umit F. (1 July 2009). "What does Al-Qanun Fi Al-Tibb (the Canon of Medicine) say on head injuries?". Neurosurgical Review. 32 (3): 255–263, discussion 263. doi:10.1007/s10143-009-0205-5. ISSN 1437-2320. PMID 19437052.

- ^ a b Tessman & Suarez, 2002

- ^ Gross 1998, p. 38

- ^ Vesalius 1543, pp. 605, 606, 609

- ^ Pestronk, A. (1 March 1988). "The first neurology book. De Cerebri Morbis...(1549) by Jason Pratensis". Archives of Neurology. 45 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1001/archneur.1988.00520270123032. PMID 3277602.

- ^ Janssen, Diederik F (10 April 2021). "The etymology of 'neurology', redux: early use of the term by Jean Riolan the Younger (1610)". Brain. 144 (4): awab023. doi:10.1093/brain/awab023. ISSN 0006-8950. PMID 33837748.

- ^ a b Scott, Alwyn C. (April 1975). "The electrophysics of a nerve fiber". Rev. Mod. Phys. 47 (2). American Physical Society: 487–533. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.47.487.

- ^ H. Helmholtz (1850). "Messungen über den zeitlichen Verlauf der Zuckung animalischer Muskeln und die Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit der Reizung in den Nerven". Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin: 276–364. Retrieved 30 January 2024. The value of 27.0 m/s can be found on page 351.

- ^ Wickens, Andrew P. (8 December 2014). A History of the Brain: From Stone Age surgery to modern neuroscience. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781317744825.

- ^ http://biomed.brown.edu/Courses/BI108/BI108_2005_Groups/03/hist.htm Archived 28 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine[full citation needed]

- ^ Preul, Mark C. (2005). "History of brain tumor surgery". Neurosurgical Focus. 18 (4): 1. doi:10.3171/foc.2005.18.4.1.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Douglas B. (1984). "The first primary brain-tumor operation". Journal of Neurosurgery. 61 (5): 809–13. doi:10.3171/jns.1984.61.5.0809. PMID 6387062.

- ^ "Alexander Hughes Bennett (1848-1901): Rickman John Godlee (1849-1925)". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 24 (3): 169–170. 1974. doi:10.3322/canjclin.24.3.169. PMID 4210862. S2CID 45097428.

- ^ "The Phineas Gage story: Surgery".

- ^ "Cyber Museum of Neurosurgery". Archived from the original on 17 October 2000. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ See Macmillan (2008), Macmillan (2002), and Phineas Gage#Theoretical use and misuse

- ^ "Neurosurgery surgical power tool - All medical device manufacturers - Videos".

- ^ "Neurosurgical Instruments, Neurosurgery Instrument, Neurosurgeon, Surgical Tools".

- ^ "Technology increases precision, safety during neurosurgery | Penn State University".

Bibliography

[edit]- Gross, Charles G. (1999) [1998]. Brain, Vision, Memory: Tales in the History of Neuroscience. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-57135-8.

- Dr.Aman PS, Sohal (2015). "children neuro condition treatment". Neuroscientist. 1 (1). Blog Publications: 216–221. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Macmillan, Malcolm (2002). An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage. MIT Press. p. 575. ISBN 978-0-262-63259-1.

- Macmillan, Malcolm (2008). "Phineas Gage – Unravelling the myth". The Psychologist. 21 (9). British Psychological Society: 828–831. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Paulissian, Robert (1991). "Medicine in Ancient Assyria and Babylonia" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 5 (1): 3–51. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- Singer, Charles (1956). "Brain Dissection Before Vesalius". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 11 (3). Oxford Journals: 261–274. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XI.3.261. PMID 13346072.

- von Staden, Heinrich (1989) [1989]. Herophilus: The Art of Medicine in Early Alexandria. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23646-0.

- Tessman, Patrick A.; Suarez, Jose I. (2002). "Influence of Early Printmaking on the Development of Neuroanatomy and Neurology". Archives of Neurology. 59 (12): 1964–1969. doi:10.1001/archneur.59.12.1964. PMID 12470188. Archived from the original on 29 August 2008.

- Vesalius, Andreas (1543). De corporis humani fabrica libri septem. Johannes Oporinus. ISBN 0-930405-75-7. available to browse online at the National Library of Medicine

- Wilkins, Robert H. (March 1964). "Neurosurgical Classic – XVII Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus". Journal of Neurosurgery. 21: 240–244. doi:10.3171/jns.1964.21.3.0240. PMID 14127631.

- "Fact sheet #168: Epilepsy: historical overview". WHO Fact Sheets. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 12 March 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.