Ancient Egyptian medicine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016) |

The medicine of the ancient Egyptians is some of the oldest documented. From the beginnings of the civilization in the late fourth millennium BC until the Persian invasion of 525 BC,[2] Egyptian medical practice went largely unchanged and included simple non-invasive surgery, setting of bones, dentistry, and an extensive set of pharmacopoeia. Egyptian medical thought influenced later traditions, including the Greeks.[3]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Sources of information

[edit]

Until the 19th century, the main sources of information about ancient Egyptian medicine were writings from later in antiquity. The Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt around 440 BC and wrote extensively of his observations of their medicinal practice.[4] Pliny the Elder also wrote favorably of them in historical review. Hippocrates (the "father of medicine"), Herophilos, Erasistratus and later Galen studied at the temple of Amenhotep, and acknowledged the contribution of ancient Egyptian medicine to Greek medicine.[5]

In 1822, the translation of the Rosetta Stone finally allowed the translation of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions and papyri, including many related to medical matters (Egyptian medical papyri). The resultant interest in Egyptology in the 19th century led to the discovery of several sets of extensive ancient medical documents, including the Ebers papyrus, the Edwin Smith Papyrus, the Hearst Papyrus, the London Medical Papyrus and others dating back as far as 2900 BC.

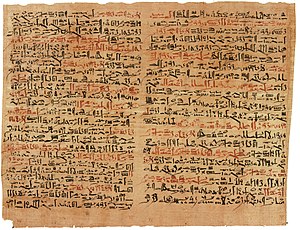

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a textbook on surgery and details anatomical observations and the "examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis" of numerous ailments.[6] It was probably written around 1600 BC, but is regarded as a copy of several earlier texts. Medical information in it dates from as early as 3000 BC.[7] It is thus viewed as a learning manual. Treatments consisted of ointments made from animal, vegetable or fruit substances or minerals.[8] There is evidence of oral surgery being performed as early as the 4th Dynasty (2900–2750 BC).[9]

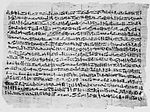

The Ebers papyrus (c. 1550 BC) includes 877 prescriptions – as categorized by a modern editor – for a variety of ailments and illnesses, some of them involving magical remedies, for Egyptian beliefs regarding magic and medicine were often intertwined.[10] It also contains documentation revealing awareness of tumors, along with instructions on tumor removal.[10]

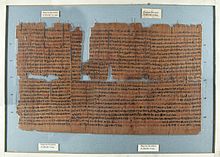

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus[11] treats women's complaints, including problems with conception. Thirty four cases detailing diagnosis and[12] treatment survive, some of them fragmentarily.[13] Dating to 1800 BC, it is the oldest surviving medical text of any kind.

Other documents such as the Hearst papyrus (1450 BC), and Berlin Papyrus (1200 BC) also provide valuable insight into ancient Egyptian medicine.

Other information comes from the images that often adorn the walls of Egyptian tombs and the translation of the accompanying inscriptions. Advances in modern medical technology also contributed to the understanding of ancient Egyptian medicine. Paleopathologists were able to use X-rays and later CAT Scans to view the bones and organs of mummies. Electron microscopes, mass spectrometry and various forensic techniques allowed scientists unique glimpses of the state of health in Egypt 4000 years ago.

Pioneers in Medical Knowledge

[edit]Warren R. Dawson, a noted medical historian, emphasized that Egypt possesses the earliest known medical texts, experimental surgeries, and medical terminology. According to Dawson, Egyptians were the first to make substantial contributions to the advancement of medicine, with medical practices dating back over five thousand years. This timeline is unsurprising, given the Egyptians' advanced knowledge in mathematics, engineering, and architecture, evidenced by their monumental structures such as the pyramids. Moreover, the ancient historian Herodotus wrote that influential rulers like Cyrus and Darius employed Egyptian physicians, indicating the high esteem in which Egyptian medical practitioners were held. These physicians documented their treatments, allowing their knowledge to be passed down through generations, and it has been found that many of their ancient methods align with practices in modern medicine.[14]

Nutrition

[edit]The ancient Egyptians were at least partially aware of the importance of diet, both in balance and moderation.[15] Owing to Egypt's great endowment of fertile land, food production was never a major issue, although, no matter how bountiful the land, paupers and starvation still exist. The main crops for most of ancient Egyptian history were emmer wheat and barley. Consumed in the form of loaves which were produced in a variety of types through baking and fermentation, with yeast greatly enriching the nutritional value of the product, one farmer's crop could support an estimated twenty adults. Barley was also used in beer. Vegetables and fruits of many types were widely grown. Oil was produced from the linseed plant and there was a limited selection of spices and herbs. Meat (sheep, goats, pigs, wild game) was regularly available to at least the upper classes and fish were widely consumed, although there is evidence of prohibitions during certain periods against certain types of animal products; Herodotus wrote of the pig as being 'unclean'. Offerings to King Unas (c. 2494–2345 BC) were recorded as "...milk, three kinds of beer, five kinds of wine, ten loaves, four of bread, ten of cakes, four meats, different cuts, joints, roast, spleen, limb, breast, quail, goose, pigeon, figs, ten other fruits, three kinds of corn, barley, spelt, five kinds of oil, and fresh plants..."

It is clear that the Egyptian diet was not lacking for the upper classes and that even the lower classes may have had some selection (Nunn, 2002).

Pharmacology

[edit]Like many civilizations in the past, the ancient Egyptians amply discovered the medicinal properties of plant life around them. The Edwin Smith Papyrus contains many recipes to help heal different ailments. One short section of the papyrus lays out five recipes: one dealing with problems women may have had, three on techniques for refining the complexion, and the fifth recipe for ailments of the colon.[16] The ancient Egyptians were known to use honey as medicine, and the juices of pomegranates served as both an astringent and a delicacy.[17] In the Ebers Papyrus, there are over 800 remedies; some were topical-like ointments and wrappings, others were oral medication such as pills and mouth rinses; still others were taken through inhalation.[18]: 15 The recipes to cure constipation consisted of berries from the castor oil tree, Male Palm, and Gengent beans, just to name a few. One recipe that was to help headaches called for "inner-of-onion, fruit-of-the-am-tree, natron, setseft-seeds, bone-of-the-sword-fish, cooked, redfish, cooked, skull-of-crayfish, cooked, honey, and abra-ointment."[18]: 44 and 60 Some of the recommended treatments made use of cannabis and incense.[19]: 156 and 158 "Egyptian medicinal use of plants in antiquity is known to be extensive, with some 160 distinct plant products..."[20] Amidst the many plant extracts and fruits, the Egyptians also used animal feces and even some metals as treatments.[21] These prescriptions of antiquity were measured out by volume, not weight, which makes their prescription-making craft more like cooking than what pharmacists do today.[19]: 140 While their treatments and herbal remedies seem almost boundless, they still included incantations along with some therapeutic remedies.[16]: 472

Egyptian drug therapy is considered ineffective by today's standards according to Michael D. Parkins, who says that 28% of 260 medical prescriptions in the Hearst Papyrus had ingredients which can be perceived "to have had activity towards the condition being treated" and another third supplied to any given disorder would produce a purgative effect on the gastrointestinal system.[22]

Practices

[edit]

Egyptians had some knowledge of human anatomy. For example, in the classic mummification process, mummifiers knew how to insert a long hooked implement through a nostril, breaking the thin bone of the braincase and removing the brain, but more commonly created a hole in the back of the head so that the brain and other fluids could drain from the foramen magnum.[23] They also had a general idea that inner organs are in the body cavity. They removed the organs through a small incision in the left groin. Whether this knowledge was passed down to the practitioners is unknown; yet it did not seem to have had any impact on their medical theories.

Egyptian physicians were aware of the existence of the pulse and its connection to the heart. The author of the Smith Papyrus even had a vague idea of the cardiac system. However, he did not know about blood circulation and deemed it unimportant to distinguish between blood vessels, tendons, and nerves. They developed their theory of "channels" that carried air, water, and blood to the body by analogies with the River Nile; if it became blocked, crops became unhealthy. They applied this principle to the body: If a person was unwell, they would use laxatives to unblock the "channels".[24][unreliable source?]

The oldest written text mentioning enemas is the Ebers Papyrus and many medications were administered using enemas. One of the many types of medical specialists was an Iri, the Shepherd of the Anus.[25]

Many of their medical practices were effective, such as the surgical procedures given in the Edwin Smith papyrus. Mostly, the physicians' advice for staying healthy was to wash and shave the body, including under the arms, to prevent infections. They also advised patients to look after their diet, and avoid foods such as raw fish or other animals considered to be unclean.[26]

Imhotep: The Healer and God of Medicine

[edit]The Egyptians also held spiritual beliefs that influenced their medical practices. They attributed certain ailments to gods, demons, and spirits with supernatural powers, and one of their most revered deities was Imhotep, the god of medicine and healing. Imhotep was known for his extensive knowledge in fields like astronomy, philosophy, architecture, poetry, and medicine. He made significant observations in medical practices, particularly in surgery and natural remedies. Revered as a “Healer of the sick,” he gained a reputation for his compassionate care toward the ill, and at least three temples were built in his honor. These temples are now important archaeological sites that demonstrate Imhotep’s influence on medicine.[14]

Surgery

[edit]The oldest metal (Bronze[27] or copper[28] [29]) surgical tools[30] in the world were discovered in the tomb of Qar. Surgery was a common practice among physicians as treatment for physical injuries. The Egyptian physicians recognized three categories of injuries; treatable, contestable, and untreatable ailments. Treatable ailments the surgeons would quickly set to right. Contestable ailments were those where the victim could presumably survive without treatment, so patients assumed to be in this category were observed and if they survived then surgical attempts could be made to fix the problem with them. They used knives, hooks, drills, forceps, pincers, scales, spoons, saws and a vase with burning incense.[31]

Circumcision of males was the normal practice, as stated by Herodotus in his Histories.[32][clarification needed] Though its performance as a procedure was rarely mentioned, the uncircumcised nature of other cultures was frequently noted, the uncircumcised nature of the Libyans was frequently referenced and military campaigns brought back uncircumcised phalli as trophies, which suggests novelty. However, other records describe initiates into the religious orders as involving circumcision which would imply that the practice was special and not widespread. The only known depiction of the procedure, in The Tomb of the Physician, burial place of Ankh-Mahor at Saqqara, shows adolescents or adults, not babies. Female circumcision may have been practiced, although the single reference to it in ancient texts may be a mistranslation.[15]

Prosthetics, such as artificial toes and eyeballs, were also used; typically, they served little more than decorative purposes. In preparation for burial, missing body parts would be replaced; however, these do not appear as if they would have been useful, or even attachable, before death.[15]

The extensive use of surgery, mummification practices, and autopsy as a religious exercise gave Egyptians a vast knowledge of the body's morphology, and even a considerable understanding of organ functions. The function of most major organs was correctly presumed—for example, blood was correctly guessed to be a transpiration medium for vitality and waste which is not too far from its actual role in carrying oxygen and removing carbon dioxide—with the exception of the heart and brain whose functions were switched.

Dentistry

[edit]Dentistry as an independent profession dated from the early 3rd millennium BC, although it may never have been prominent. The Egyptian diet was high in abrasives from sand left over from grinding grain and bits of rocks in which the way bread was prepared, and so the condition of their teeth was poor. Archaeologists have noted a steady decrease in severity and incidence of worn teeth throughout 4000 BC to 1000 AD, probably due to improved grain grinding techniques.[19] All Egyptian remains have sets of teeth in quite poor states. Dental disease could even be fatal, such as for Djedmaatesankh, a musician from Thebes, who died around the age of thirty five from extensive dental disease and a large infected cyst. If an individual's teeth escaped being worn down, cavities were rare, due to the rarity of sweeteners. Dental treatment was ineffective and the best sufferers could hope for was the quick loss of an infected tooth. The Instruction of Ankhsheshonq contains the maxim "There is no tooth that rots yet stays in place".[15] No records document the hastening of this process and no tools suited for the extraction of teeth have been found, though some remains show sign of forced tooth removal.[19] Replacement teeth have been found, although it is not clear whether they are just post-mortem cosmetics. Extreme pain might have been medicated with opium.[15]

Doctors and other healers

[edit]

The ancient Egyptian word for doctor is "swnw". This title has a long history. The earliest recorded physician in the world[citation needed], Hesy-Ra, practiced in ancient Egypt. He was "Chief of Dentists and Physicians" to King Djoser, who ruled in the 27th century BC.[33] The lady Peseshet (2400 BC) may be the first recorded female doctor: she was possibly the mother of Akhethotep, and on a stela dedicated to her in his tomb she is referred to as imy-r swnwt, which has been translated as "Lady Overseer of the Lady Physicians" (swnwt is the feminine of swnw).[citation needed]

There were many ranks and specializations in the field of medicine. Royalty employed their own swnw, even their own specialists. There were inspectors of doctors, overseers and chief doctors. Known ancient Egyptian specialists are ophthalmologist, gastroenterologist, proctologist, dentist, "doctor who supervises butchers" and an unspecified "inspector of liquids". The ancient Egyptian term for proctologist, neru phuyt, literally translates as "shepherd of the anus". The latter title is already attested around 2200 BC by Irynachet.

Institutions, called (Per Ankh)[34] or Houses of Life, are known to have been established in ancient Egypt since the 1st Dynasty and may have had medical functions, being at times associated in inscriptions with physicians, such as Peftauawyneit and Wedjahorresnet living in the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[35] By the time of the 19th Dynasty their employees enjoyed such benefits as medical insurance, pensions and sick leave.[33]

Table of ancient Egyptian physicians

[edit]| Physician Name | Other names | Kings service & Dating | Titles | Gender | Medical practice Site | Medical legacy | Non medical legacy | Burial site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imhotep | Egyptian ỉỉ-m-ḥtp *jā-im-ḥātap meaning "the one who comes in peace, is with peace", Immutef, Im-hotep, or Ii-em-Hotep; called Imuthes (Ἰμούθης) | Djoser circa 2650–2600 BC | Chancellor of the King of Egypt, Doctor, First in line after the King of Upper Egypt, Administrator of the Great Palace, Hereditary nobleman, High Priest of Heliopolis, Builder, Chief Carpenter, Chief Sculptor, and Maker of Vases in Chief. | M | Memphis | Two thousand years after his death, Imhotep's status was raised to that of a deity of medicine and healing. Whether he was actually a physician is debated. | Imhotep was one of the chief officials of the Pharaoh Djoser and Egyptologists ascribe to him the designed the Pyramid of Djoser (the Step Pyramid) at Saqqara in Egypt in 2630–2611 BC. He may have been responsible for the first known use of columns to support a building. The Egyptian historian Manetho credited him with inventing the method of a stone-dressed building during Djoser's reign. | Probably Saqqara |

| Hesy-Ra | re-hesy, Hesire, Hesira | Djoser c. 2670 BC | Great one of the dentists | M | N/A | possibly the first known dentist in history | Wooden panel set of Hesy-Ra | buried in an elaborate tomb at Saqqara |

| Medunefer | N/A | Old Kingdom c. 2500 BC | leader of the eye physicians of the palace | M | N/A | Known from his mastaba at Giza | N/A | |

| Penthu | N/A | Akhenaten c. 1350 BC, and later | The sealbearer of the King of Lower Egypt, the sole companion, the attendant of the Lord of the Two Lands, the favorite of the good god, king's scribe, the king's subordinate, First servant of the Aten in the mansion of the Aten in Akhetaten, Chief of physicians, and chamberlain | M | Aten | Chief physician to Akhenaten, but may have survived the upheavals of the end of the Amarna period, and served under Ay, after being Vizier under Tutankhamun | Vizier to king | Amarna Tomb 5 |

| Peseshet | N/A | Fourth Dynasty of Egypt c. 2500 BC | lady overseer of the female physicians | F | N/A | Midwife (?), earliest known female physician in ancient Egypt | A personal stela at her son Akhethetep's tomb | N/A |

| Qar | N/A | Sixth Dynasty of Egypt c. 2350–2180 BC | The royal physician | M | N/A | The oldest Bronze or copper surgical tool in the world | His mummy in the limestone sarcophagus and 22 bronze statues of different deities and statuette of Imhotep the physician | He died at the age of fifty years and was buried in his tomb at Saqqara, which was re-used several times |

| Psamtikseneb | may King Psamtik be healthy | Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt c. 664–525 BC | The Head of Physicians, the scorpion charmer, chief physician and chief dentist (wr ἰbḥ) of Psamtik Seneb, an admiral of the royal fleet | M | N/A | N/A | Ushabti of the Head of Physician Psamtik-seneb, photo in relief of Ankh-ef-en-Sekhmet Entertained by a Harpist | His tomb discovered at Heliopolis in 1931/32 AD |

| Udjahorresnet | Wedjahor-Resne or Udjahor-Resnet | from Amasis to Darius I | The Head of Physicians, supervisor of the medical schools – the 'Houses of life'; the prince, the royal chancellor, the unique companion, the prophet of the one who lives with them, the chief physician, the one truly known and loved by the king, the scribe, the inspector of the scribes of the dedet-court, the first among the great scribes of the prison, the director of the palace, the admiral of the royal navy of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Khnemibre [Amasis], the admiral of the royal navy of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ankhkaenre [Psammetichus III], head of the province of Sais Peftuôneit | M | N/A | Wedjahor-Resne composed Cambyses' new royal name, Mesuti-Ra ('born of Ra') | His titles are preserved on a beautiful statue (Vatican inv.196) | His tomb[36] has been discovered in 1995 at Abusir[37][38][39] |

| Harsiese son of Ramose | 00 | from Amasis to Darius I | The Head of Physicians, chief physician of Upper and Lower Egypt, leader of Aegean foreign (troops) and admiral of the royal fleet | M | N/A | N/A | mentioned in Instruction of Ankhsheshonq (P. BM 10508) as the source of the plot that led to the imprisonment of the unfortunate Ankhsheshonq (P. BM. 10508 col. 1 to 3) | Saqqara[38] |

| Peftuaneith | Payeftjauemawyneith | Twenty-sixth Dynasty during the reign of Amasis[38] | The Chief physician | M | N/A | N/A | A naophorous statue of the chief physician Petuaneith (Louvre A 93), he restored the temple of Abydos | N/A |

| Iwti | N/A | 19th dynasty c. 2500 BC[inconsistent] | The Chief physician | M | Most likely worked or trained in Memphis (inscriptions on statue indicate sacrificial relations to Memphite city god)[40] | N/A | A statue of him is displayed at the museum of Egyptology in Leiden[41] | N/A |

| Djehutyemheb | N/A | Ramesses II | The wise scribe and physician | M | Khonsu temple? | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Peftjauemauineith | N/A | transitional period between Apries and Amasis II | the chief physician of Upper and Lower Egypt (wr swnw n sma MHw) | M | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Table of ancient Egyptian medical papyri

[edit]| Papyrus Name | Other names | Dating | Language | Medical specialties | Contents | Scribe/Author | Date & place of discovery | place of preserving | size | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwin Smith Papyrus | Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus | dates to Dynasties 16–17 of the Second Intermediate Period in ancient Egypt, c. 1500 BC, but believed to be a copy from Old Kingdom, 3000–2500 BC | Hieratic | The oldest known surgical treatise on trauma | The vast majority of the papyrus is concerned with trauma and surgery, with short sections on gynaecology and cosmetics on the verso. On the recto side, there are 48 cases of injury. The verso side consists of eight magic spells and five prescriptions. The oldest known surgical treatise on trauma | Attributed by some to Imhotep | Luxor, Egypt before 1862 | New York Academy of Medicine | a scroll 4.68 m in length. The recto (front side) has 377 lines in 17 columns, while the verso (backside) has 92 lines in five columns |

|

| Ebers Papyrus | Papyrus Ebers | c. 1550 BC but believed to be a copy from earlier texts of 3400 BC | Hieratic | Medicine, Obestitrics & gynecology & Surgery | The scroll contains some 700 magical formulas and remedies, chapters on contraception, diagnosis of pregnancy and other gynecological matters, intestinal disease and parasites, eye and skin problems, dentistry and the surgical treatment of abscesses and tumors, bone-setting and burns | N/A | Assassif district of the Theban necropolis before 1862 | Library of University of Leipzig, Germany | a 110-page scroll, which is about 20 meters long |

|

| Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus | Kahun Papyrus, Kahun Medical Papyrus, or UC 32057 | c. 1800 BC | Hieratic | Medicine, Obestitrics & gynecology, pediatrics and veterinary medicine | The text is divided into thirty-four sections that deals with women's health—gynaecological diseases, fertility, pregnancy, contraception, etc. The later Berlin Papyrus and the Ramesseum Papyrus IV cover much of the same ground, often giving identical prescriptions | N/A | El-Lahun by Flinders Petrie in 1889 | University College London | 2 gynecologic papyri & 1 veterinary payrus |

|

| Ramesseum medical papyri | Ramesseum medical papyri parts III, IV, and V | 18th century BC | Hieroglyphic & Hieratic | Medicine, gynecology, ophthalmology, rheumatology & pediatrics | A collection of ancient Egyptian medical documents in parts III, IV, and V, and written in vertical columns that mainly dealt with ailments, diseases, the structure of the body, and supposed remedies used to heal these afflictions. namely ophthalmologic ailments, gynaecology, muscles, tendons, and diseases of children | N/A | Ramesseum temple | Oxford Ashmoulian Museum | 3 papyri (parts III, IV, V) | N/A |

| Hearst papyrus | Hearst Medical Papyrus | 18th Dynasty of Egypt, around time of Tuthmosis III c. 0000 but believed to have been composed earlier, during the Middle Kingdom, around 2000 BC | Hieratic | Urology, Medicine and bites | 260 paragraphs on 18 columns in 18 pages of medical prescriptions for problems of urinary system, blood, hair, and bites | N/A | discovered by an Egyptian peasant of village of Der-el-Ballas before 1901 | Bancroft Library, University of California | 18 pages |

|

| London Medical Papyrus | BM EA 10059 | 19th dynasty 1300 BC or c. 1629–1628 BC | Hieratic | skin complaints, eye complaints, bleeding, miscarriage and burns | 61 recipes, of which 25 are classified as medical the remainder are of magic | N/A | N/A | Royal institute of London |

| |

| Papyrus Berlin 3038 | Brugsch Papyrus, the Greater Berlin Papyrus | 19th dynasty, and dated c. 1350–1200 BC | Hieratic? | Medical | discussing general medical cases and bears a great similarity to the Ebers papyrus. Some historians believe that this papyrus was used by Galen in his writings | 24 pages (21 to the front and 3 on the back) | N/A | Discovered by an Egyptian in Saqqara before 1827 | Berlin Museum | N/A |

| Carlsberg papyrus | N/A | between the 19th and 20th dynasties, New Kingdom; its style relates it to the 12th dynasty. Some fragments date back to c. 2000 BC, others—the Tebtunis manuscripts—date back to c. 1st century AD | Hieratic, Demotic. Hieroglyphs and in Greek | Obestitrics & gynecology, Medicine, Pediatrics & ophthalmology | The structure of the papyrus bears great resemblance to that of the Kahun and Berlin papyri. | N/A | N/A | N/A | Egyptological Institute of the University of Copenhague | N/A |

| Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus | Chester Beatty Papyri, Papyrus VI of the Chester Beatty Papyri 46 (Papyrus no. 10686, British Museum), Chester Beatty V BM 10685, VI BM 10686, VII BM 10687, VIII BM 10688, XV BM 10695 | dated around 1200 BC] | Hieratic? | Headache, and Anorectal disorders | Magic spells and medical recipes for headache & anorectal disease | N/A | started off as a private collection by the scribe Qen-her-khepeshef in the 19th Dynasty and passed on down through his family until they were placed in a tomb | Deir el-Medina (the workers village) in 1928 | British Museum | N/A |

| Brooklyn Papyrus | 47.218.48 och 47.218.85, also known as the Brooklyn Medical Papyrus | a collection of papyri which belong to the end of the 30th dynasty, dated to around 450 BC, or the beginning of the Ptolemaic Period. However, it is written with the Middle Kingdom style which could suggest its origin might be from the Thirteenth dynasty of Egypt | Hieratic? | deals only with snakes and scorpion bites, and the formulae to drive out the poison of such animals | It speaks about remedies to drive out poison from snakes, scorpions and tarantulas. The style of these remedies relates to that of the Ebers papyrus | a scroll of papyrus divided into two parts with some parts missing, its total length is estimated to 175 × 27 cm | N/A | might originate from a temple at ancient Heliopolis, discovered before 1885 | Brooklyn Museum in New York |

|

| Erman Papyrus | given with the Westcar papyrus to Berlin museum | Middle dated from the beginning of the New Kingdom (16th century BC) | ??? | Medicine, Magic & Anatomy | Holds some medical formulae and a list of anatomic names (body and viscera) and about 20 magical formulae | N/A | N/A | before 1886 AD | Berlin Museum | N/A |

| Leiden Papyrus | Rijksmuseum, Leiden 1343–1345 | 18th–19th dynasties | ??? | Medicine, Magic | It mostly deals with magical texts | N/A | N/A | N/A | Rijks museum, Leiden |

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wilkins, Robert H. (1992) [First published 1965]. Neurosurgical Classics (2nd ed.). Park Ridge, Illinois: American Association of Neurological Surgeons. ISBN 978-1-879284-09-8. LCCN 2011293270.<

- ^ Metwaly AM, Ghoneim MM, Eissa IH, Elsehemy IA, Mostafa AE, Hegazy MM, et al. (October 2021). "Traditional ancient Egyptian medicine: A review". Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 28 (10): 5823–5832. Bibcode:2021SJBS...28.5823M. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.06.044. PMC 8459052. PMID 34588897.

- ^ Steinbock RT (1990). "The Medical Skills of Ancient Egypt". JAMA. 264 (23): 3074. doi:10.1001/jama.1990.03450230110044.

- ^ Jouanna, Jacques; Allies, Neil (2012), "Egyptian Medicine and Greek Medicine", Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen, Brill, pp. 3–20, JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76vxr.6

- ^ Said, Galal Zaki (17 November 2013). "Orthopaedics in the dawn of civilisation, practices in ancient Egypt". International Orthopaedics. 38 (4): 905–909. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2183-z. ISSN 0341-2695. PMC 3971265. PMID 24240438.

- ^ "Edwin Smith papyrus (Egyptian medical book)". Encyclopedia Britannica (Online ed.). Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Arab, Sameh M. "Medicine in Ancient Egypt – Part 1". Arab World Books. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Fagan, Brian M. (2004). The Seventy Great Inventions of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50005130-6.

- ^ Weinberger, Bernhard Wolf (1946). "Further Evidence That Dentistry Was Practiced in Ancient Egypt, Phoenicia and Greece". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 20 (2): 188–195. JSTOR 44441040. PMID 20277446. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ a b Dawson, Warren R. (1927). "The Beginnings of Medicine: Medicine and Surgery in Ancient Egypt". Science Progress in the Twentieth Century (1919-1933). 22 (86): 275–284. JSTOR 43430010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Griffith, F. Ll. (1898). The Petrie Papyri: Hieratic Papyri from Kahun and Gurob. London: Bernard Quaritch. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2016. (Please note the book pages run from back to front.)

- ^ Bynum, W. F.; Hardy, Anne; Jacyna, Stephen; Lawrence, Christopher; Tansey, E.M. (2006). "The Rise of Science in Medicine, 1850–1913". The Western Medical Tradition: 1800–2000. Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-0-521-47565-5.

- ^ Dollinger, André. "The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus". An introduction to the history and culture of Pharaonic Egypt. Kibbutz Reshafim. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b Ibrahim, Eltorai (2020). A Spotlight on the History of Ancient Egyptian Medicine. New York CRC Press. pp. 59–68.

- ^ a b c d e Dollinger, André (December 2002). "Ancient Egyptian Medicine". An introduction to the history and culture of Pharaonic Egypt. Kibbutz Reshafim. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b Breasted, James Henry (1930). The Edwin Smith Papyrus. University of Chicago Oriental Institute publications ;3-4. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Allen, James P (2005). The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-10728-9. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b Bryan, Cyril (1932). The Ebers Papyrus. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- ^ a b c d Nunn, John F. (1996). Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Vol. 113. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 57–68. ISBN 978-0-8061-2831-3. PMID 10326089.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Ritner, Robert K. (April 2000). "Innovations and Adaptations in Ancient Egyptian Medicine". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 59 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1086/468799. JSTOR 545610. PMID 16468204. S2CID 39263523.

- ^ Dollinger, André. "Herbal Medicine". An introduction to the history and culture of Pharaonic Egypt. Kibbutz Reshafim. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ Parkins, Michael D.; Szekrenyes, J. (March 2001). "Pharmacological Practices of Ancient Egypt" (PDF). Proceedings of the 10th Annual History of Medicine Days. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: The University of Calgary. pp. 5–11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi A. (2018). Scanning the Pharaohs : CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-887-1. OCLC 1078493215. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "What progress did the Egyptians make in medical knowledge?". Medicine Through Time: Model Questions and Answers. Passmores Academy. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Magner, Lois (1992). A History of Medicine. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8247-8673-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Stiefel, Marc; Shaner, Arlene; Schaefer, Steven D. (February 2006). "The Edwin Smith Papyrus: The Birth of Analytical Thinking in Medicine and Otolaryngology". The Laryngoscope. 116 (2): 182–188. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000191461.08542.a3. ISSN 0023-852X. PMID 16467701. S2CID 35256503.

- ^ El-Aref, Nevine (December 2006). "Too big for a coffin". Al-Ahram Weekly. Cairo, Egypt: Al-Ahram. Archived from the original on 18 November 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi (2003). "The tomb of the physician Qar". Hidden Treasures of the Egyptian Museum: One Hundred Masterpieces from the Centennial Exhibition (Supreme Council of Antiquities ed.). Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. p. xx. ISBN 978-977424778-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Lauer, Jean Philippe (3 January 2013). "Imhoteb Museum". Egypt Tourism News. Egypt Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Jackson, Russell (6 December 2006). "Mummy of ancient doctor comes to light". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Greiner, Ryan (2001). "Ancient Egyptian Medicine". Creighton University Virtual Museums. Creighton University. Archived from the original on 23 December 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ Herodotus (25 February 2006) [First published 1890]. An Account of Egypt (from The History of Herodotus Translated into English, Vol. I, Pages 115–208). Translated by Macaulay, G. C. Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b Arab, Sameh M. "Medicine in Ancient Egypt – Part 3". Arab World Books. Archived from the original on 24 January 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Gordan, Andrew H.; Shwabe, Calvin W. (2004). The Quick and the Dead: Biomedical Theory in Ancient Egypt. Egyptological Memoirs. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 978-90-04-12391-5.

- ^ Grajetzki, Wolfram; Quirke, Stephen (2003). "Knowledge and production: the House of Life". Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. Archived from the original on 31 December 2003. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Bareš, Ladislav (2005). "The Shaft Tomb of Udjahorresnet". Czech Institute of Egyptology. Charles University in Prague. Archived from the original on 7 July 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Wood, Gemma Ellen (4 July 2012). "Dispelling the myth – Herodotus, Cambyses, and Egyptian religion #1". The Egyptiana Emporium. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Agut-Labordère, Damien (2013). "The Saite Period: The Emergence of a Mediterranean Power". Ancient Egyptian Administration. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 965–1027. ISBN 978-90-04-24952-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Wedjahor-Resne". Livius.org. Jona Lendering. 22 August 2015. Archived from the original on 25 December 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Fonahn, Adolf (1 January 1909). "Der altägyptische Arzt Iwti". Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin. 2 (5): 375–378. JSTOR 20772830.

- ^ Fonahn, Adolf (February 1909). "Der altägyptische Arzt Iwti". Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin (in German). 2 (5): 375–378. JSTOR 20772830.

Further reading

[edit]- English

- Ancient Egyptian Medicine, John F. Nunn, 1996

- The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A medical History of Humanity, Roy Porter, 1997

- A History of Medicine, Lois N. Magner, 1992

- Medicine in the Days of the Pharaohs, Bruno Halioua, Bernard Ziskind, M. B. DeBevoise (Translator), 200

- Pharmacological practices of ancient Egypt, Michael D. Parkins, 10th Annual Proceedings of the History of Medicine Days, 2001

- Pain, Stephanie. (2007). "The pharaohs' pharmacists." New Scientist. 15 December 2007, pp. 40–43

- French

- Ange Pierre Leca, La Médecine égyptienne au temps des Pharaons, éd. Dacosta, Paris, 1992 (ISBN 2-851-28-029-5)

- Thierry Bardinet, Les papyrus médicaux de l'Égypte pharaonique, éd. Fayard, Paris, 1995 (ISBN 2-213-59280-2)

- Histoire de la médecine en Egypte ancienne, Paris, 2013– (http://medecineegypte.canalblog.com/)

- Richard-Alain Jean, À propos des objets égyptiens conservés du musée d’Histoire de la Médecine, éd. Université René Descartes – Paris V, coll. Musée d'Histoire de la Médecine de Paris, Paris, 1999 (ISBN 2-9508470-3-X)

- Richard-Alain Jean, La chirurgie en Égypte ancienne. À propos des instruments médico-chirurgicaux métalliques égyptiens conservés au musée du Louvre, Editions Cybele, Paris, 2012 (ISBN 978-2-915840-29-2)

- Richard-Alain Jean, Anne-Marie Loyrette, À propos des textes médicaux des Papyrus du Ramesseum nos III et IV, I : la reproduction, in S.H. Aufrère (éd.), Encyclopédie religieuse de l’Univers végétal (ERUV – II), Montpellier, 2001, pp. 537–564 (ISBN 978-2-84269-502-6)

- Richard-Alain Jean, Anne-Marie Loyrette, À propos des textes médicaux des Papyrus du Ramesseum nos III et IV, I : la contraception, in S.H. Aufrère (éd.), Encyclopédie religieuse de l’Univers végétal (ERUV – II), Montpellier, 2001, pp. 564–592 (ISBN 978-2-84269-502-6)

- Bruno Halioua, La médecine au temps des Pharaons, éd. Liana Levi, coll. Histoire lieu, Paris, 2002 (ISBN 2-867-46-306-8)

- Richard-Alain Jean, Anne-Marie Loyrette, À propos des textes médicaux des Papyrus du Ramesseum nos III et IV, I : la gynécologie (1), in S.H. Aufrère (éd.), Encyclopédie religieuse de l’Univers végétal (ERUV – III), Montpellier, 2005, pp. 351–487 (ISBN 2-84269-695-6)

- Richard-Alain Jean, Anne-Marie Loyrette, La mère, l’enfant et le lait en Égypte Ancienne. Traditions médico-religieuses. Une étude de sénologie égyptienne, S.H. Aufrère (éd.), éd. L’Harmattan, coll. Kubaba – Série Antiquité – Université de Paris 1, Panthéon Sorbonne, Paris, 2010 (ISBN 978-2-296-13096-8)

- German

- Wolfhart Westendorf, Handburch der altägyptischen Medizin, éd. Brill, coll. HdO, Leiden, 1999 (Band 1 : ISBN 90-04-11320-7, Band II : ISBN 90-04-11321-5)

External links

[edit]- Medicine in Old Egypt – Transcript from History of Science by George Sarton

- Ancient Egyptian Medicine – Aldokkan

- Ancient Egyptian Medicine

- Brian Brown (ed.) (1923) The Wisdom of the Egyptians. New York: Brentano's

- Texts from the Pyramid Age by Nigel C. Strudwick, Ronald J. Leprohon, 2005, Brill Academic Publishers

- Ancient Egyptian Science: A Source Book by Marshall Clagett, 1989

- (in French) Site sur la médecine et la chirurgie dans l'Antiquité Egyptienne.

- (in French) Ancient medicine website