History of Caltanissetta

This entry is about the history of Caltanissetta, a municipality in the central interior of Sicily, Italy, and the capital of the Province of Caltanissetta, from prehistory to the present day. The city, whose recorded history begins with the Norman occupation in 1086, was damaged during heavy fighting in World War II. It has several sites of historical interest, including the ruins of Pietrarossa Castle, the Abbey of Santo Spirito, and several 19th-century neoclassical palaces. From the 18th century, the city supported an important sulphur mining industry, although the mines were abandoned in the late 20th century.[1]

From prehistory to late antiquity

[edit]Early Sicanian villages

[edit]

Although some worked flints found at the site of Gibil Gabib[2] and other archaeological finds attributable to the Copper Age testify that the territory of Caltanissetta was inhabited as early as the 4th millennium B.C., the earliest known urban nuclei are some Bronze Age villages that arose around the 19th century B.C. on the main heights west of the southern Imera: Gibil Gabib, Sabucina, Vassallaggi, San Giuliano, and Capodarso. At least five have been identified within the municipal territory.[3]

The inhabitants of these villages, which Diodorus Siculus identifies as Sicani, can be traced back to the Castelluccio culture: they were predominantly sedentary farmers, also occasionally engaged in pastoralism and hunting. Each nucleus maintained its own political autonomy, and was endowed with its own necropolis, but similar to other Castelluccio sites, it is hypothesized that they constituted a single social and economic entity, even sharing the same place of worship, which has been identified at Mount San Giuliano. At the same time, however, the absence of imported objects among the archaeological finds indicates an attitude of closure and distrust of the outside world.[4]

Sabucina

[edit]

Around 1270 B.C. the Castelluccio villages were abandoned and a new one was built perched on top of Mount Sabucina. This was a phenomenon similar to what happened to the rest of Sicily in response to the invasion of the Sicels, a people from the Italic peninsula who settled in the eastern part of the island: the inhabitants of small, defenseless villages gathered together by founding one in a safer and more defensible place, and the natural conformation of Mount Sabucina and its location, west of the "border" along the Himera River with the Sicels, met the defensive needs of the inhabitants of the present-day territory of Caltanissetta. Given the impossibility of tracing the original name of the site, this settlement is referred to by the contemporary toponym of the locality, Sabucina.[3]

At an early stage, it progressed seamlessly with the Castelluccio culture, although it presented a more evolved society also depending on the hostility with neighboring enemies, as evidenced by the production of very complex and functional objects, but with few simple decorative elements. The site was abruptly abandoned after three centuries, probably due to incursion and looting by the Sicels.[4]

Sabucina became inhabited again in the eighth century B.C., some two hundred years after its sudden abandonment, by local peoples who were heirs of the ancient Sicels and Sicani now integrated and intermingled. Once the needs of war ceased, the strategic position of the village was used to control the main access route from the coast to the hinterland, represented by the Imera valley, which favored the birth of a flourishing commercial exchange with Greeks and Carthaginians settled along the coast, as shown by some objects found there. During this period, the other sites abandoned in the 13th century also became inhabited again. In Sabucina, Greek culture slowly replaced the indigenous one; initially it had privileged relations with Gela, but in the 6th century B.C. it entered the area of influence of Akragas, probably as a result of the conquest by the tyrant Phalaris during his campaign to conquer the hinterland as far as the colony of Himera, on the Tyrrhenian coast of the island. During the Agrigentine period Sabucina experienced a golden age, galvanized by a flourishing agriculture and intense trade with Akragas, but it never became its own subcolony, and indeed retained its own indigenous identity as shown by works dating from that period, including the Sabucina sacellum.[4]

During the fifth century B.C.E. a phase of decline of the village is observed, beginning at the same time as the war that Ducetius, king of the Sicels, unleashed against the large Hellenized centers of the hinterland. It has therefore been assumed that Sabucina remained involved in the war, and some historians have gone so far as to associate it with Motyon, a city destroyed by Ducetius and not yet precisely identified. In any case, Sabucina was finally abandoned around 400 B.C.E., and Timoleon's subsequent attempts to repopulate it in 310 B.C.E. also failed.[4]

Roman and Byzantine eras

[edit]There is no evidence to support the existence of an urban center in the territory of Caltanissetta during the Roman period; for instance, of all the island settlements mentioned by Cicero in the In Verrem, none can be traced back to Caltanissetta or ancient Sabucina; the same archaeological findings show that the territory must have been distant from inhabited places. The almost total absence of urban centers in the Sicilian hinterland during this phase of history can be explained by the fact that, following the Roman conquest of Sicily, the territory began to be managed according to the latifundium scheme; this, combined with the advent of the pax romana, which made all defensive systems superfluous, caused the disappearance of numerous perched villages in place of a concentration of human activities in a few urban centers located at the bottom of the valley. The same situation can be seen in the subsequent Byzantine period, during which the presence of a few rural villas cannot be ruled out, but no real urban settlement can be mentioned.[4]

Foundation of the city

[edit]

The earliest documents in which the city's name appears date back to Norman times.[5] The first to mention a toponym traceable to Caltanissetta was in the 11th century the personal chronicler of the Great Count Roger, Goffredo Malaterra, who narrated the Norman conquest of Sicily; he lists it, with the name of Calatenixet, among the eleven strongholds conquered to encircle and isolate the Emir of Enna:[6]

—Goffredo Malaterra, De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae comitis et Roberti Guiscardi ducis fratris eius

Caltanissetta is the only toponym for which Malaterra takes care to provide a Latin translation, moreover confirmed later: the toponym in fact derives from the Arabic Qalʿat an-nisāʾ, literally translatable as "fortress of women" (or "castle of women"), which is the name by which the Arab geographer Idrisi referred to the city in 1154 in The Book of Roger.[5]

However, based on his studies of the origin of the place name Caltanissetta, scholar Luigi Santagati argues that the first people to inhabit the present site of the town may have been the Byzantines, who in the second half of the 8th century would have built the castle of Pietrarossa and the adjoining village that they would have named Nissa after the possible name of the city of origin of the town's founding stratiotes. Founders who in 730, or more likely during the iconoclastic period between 730 and 787,[7] emigrated from ancient Nissa of the Hittites,[8] now Nevşehir, from the province of the same name in central Anatolia.[9]

Later with the arrival of the Arabs, around 846, the name would become Qalʿat an-nisāʾ out of assonance with the old Byzantine name.[10][11]

Textually, Santagati writes: "At the origin of the name of Caltanissetta, therefore, there may have been a homogeneous settlement of stratiotes from the first Greek, then Roman and Byzantine city of Nissa, today known as Nevşehir, located in Cappadocia (Turkey). The region from 730 suffered a very serious socio-economic crisis that forced a large part of the population to move elsewhere; a small part of it may have settled at the site of present-day Caltanissetta, calling it by its original name. Once it fell to the Arabs the settlement would have assumed the name Qal'at an-Nissa or Nisa (fortress of Nisa) hence the easy confusion with the Arabic term nisa or nisah (women) plural of marah (woman)."[9]

In support of this hypothesis is the circumstance of the life of Gregory of Nyssa (Caesarea in Cappadocia, 335 - Nyssa, c. 395): he was an ancient Greek bishop and theologian, and in 371 he was appointed bishop of the Diocese of Nyssa;[12] he is venerated by all the Christian Churches, and is one of the Cappadocian Fathers;[13] and is considered one of the most expressive Eastern Fathers of the fourth century. He died between the years 395 and 400 and his feast is celebrated on March 9.[12]

From the Arabs to the Aragonese Dynasty

[edit]10th-11th century: Emirate of Sicily

[edit]

As in the rest of the island, in spite of the great impact that Islamic culture left on the territory, from language to agricultural techniques and cuisine, there is little architectural evidence in the territory of Caltanissetta dating from this historical period. Among them is a fortified rural farmhouse, now incorporated within the complex of the Abbey of the Holy Spirit, of which a massive rectangular building topped by a lookout tower is clearly recognizable, surrounded by walls equipped with a gateway with anti-besiegement systems, since, due to its remoteness from the village, it must have been able to provide for its own defense independently. It is likely that the Pietrarossa castle (or part of it) was also built during this period. Finally, faint traces remain in the urban layout of the Santa Domenica district, which certainly corresponds to the Arab suburb, although it is impossible to establish its exact boundaries with certainty; triangular courtyards overlooked by the main facades of the dwellings, typical of the Islamic world, can still be seen in it.[5]

11th-12th century: the Kingdom of Sicily

[edit]

In 1061 Roger of Hauteville landed in Sicily, initiating the Norman conquest of the island, which would end thirty years later, in 1091, with the fall of Noto. Caltanissetta, along with eleven other "fortresses" located between Agrigento and Enna, was conquered by Roger in 1086, a year before the final battle against the Emir of Enna Ibn al-ʿAwwās, from which the latter emerged defeated, which probably took place near Capodarso, where the bridge of the same name stands today.[14]

Among the first measures of the Great Count Roger was the subdivision of the island into dioceses and the appointment of their bishops; among these, the diocese of Agrigento, founded in 1093, had as its eastern border the southern Imera, and thus included the territory of Caltanissetta. In order to convert the Muslim population, the construction of a network of rural churches was planned, including the Abbey of Santo Spirito,[14] the city's first parish,[15] carved out of a fortified Arab farmhouse; the church of San Giovanni, which in 1101 was reported to be among the dependencies of the Abbey of the Holy Trinity of Mileto, is also mentioned as a "church outside the walls" in a bull by Eugene III in 1150.[15] At the same time, the territory was divided among various feudal lords. The earliest feudal lord of Caltanissetta of whom there are certain records is Goffredo di Montescaglioso. He took part along with other Sicilian nobles in a conspiracy against Maio of Bari, adviser to King William the Bad, but the conspiracy failed and Goffredo was blinded and deprived of his property; the fief of Caltanissetta then in 1167 was assigned to Queen Margaret's half-brother and brother-in-law of the king, Henry of Navarre, who, however, because of his unrestrained lifestyle, was removed by the queen in 1170.[16] Left without a feudal lord, the city then became state-owned, that is, under direct royal jurisdiction, and remained so even under the subsequent Swabian and Angevin dominations.[17]

13th century: from Frederick II to the Sicilian Vespers

[edit]A peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Normans had been established in the first century of Norman rule, but this harmony broke down in the early 13th century, when the Arabs began to reject the king's authority and claim their own self-rule. This prompted the new king Frederick II of Swabia to wage a ruthless war against the Muslims, culminating in the deportation to Lucera of those who refused to convert. At the same time he attempted to curb the power of the barons by directly administering numerous fiefdoms. In Caltanissetta the figure of the "royal chaplain" was established, a religious authority who exercised power on behalf of the king, and who was based in the new church dedicated to Our Lady, built in 1225 at the castle of Pietrarossa, and not within the village, precisely to represent royal power over the territory.[18] According to many scholars this would be the church known today as Santa Maria degli Angeli, although some evidence has led scholar Daniela Vullo to identify it as a chapel that was built inside the castle and collapsed with it in 1567.[19]

During the troubled phases that followed Frederick II's death, Caltanissetta, along with Agrigento, Catania, Agosta and other Sicilian cities sided with Conradin of Swabia, Frederick's nephew and his legitimate heir; the imperial general Nicolò Maletta set up his headquarters precisely in the castle of Pietrarossa, which was considered unconquerable. When Charles I of Anjou prevailed over the other pretenders, he imposed a harsh regime on the cities that opposed him. Caltanissetta was entrusted to the French military man Raul de Grollay, and after a long siege of the castle, around 1268 Maletta was captured and killed, complicit in the treachery of his own men.[20]

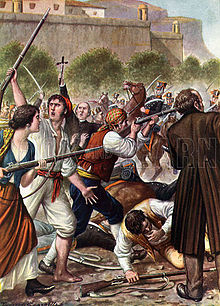

In the spring of 1282, following the Sicilian Vespers, the citizens of Caltanissetta joined the uprisings that broke out all over the island, and after ousting the Angevins, they organized themselves into the "Free Commune of Caltanissetta," which, however, was short-lived: in difficulty against the French, the Sicilians asked for and obtained the help of Peter III of Aragon, who already by the end of that year proclaimed himself king of Sicily and put an end to the various communal governments, including that of Caltanissetta.[21]

14th century: from the House of Lancia to the House of Peralta

[edit]

During the first years in which the Aragonese Dynasty ruled Sicily, the Catalans Bernard de Sarrià and Ramon Almany succeeded each other as castellans of the city; the latter, perched in the castle of Pietrarossa together with some nobles loyal to him, tried in 1295 to oppose the appointment of Frederick III of Sicily as king by threatening secession, but was persuaded peacefully to desist. Having sent the secessionists back to Spain, the new king appointed new feudal lords in 1296, including Corrado I Lancia, to whom he entrusted the fiefdom of Caltanissetta.[22] Upon the latter's death, the fiefdom was the object of the attentions of the new husband of Corrado Lancia's widow, Pedro Ferrandis de Vergua, who tried in every way to gain possession of it. When discovered, he fled to Tunis to avoid imprisonment, and the fiefdom then passed to the rightful heir Pietro Lancia, Corrado's nephew.[23] After the marriage in 1342 of Pietro's eldest daughter Cesarea to the brother of King Peter II of Sicily, John of Randazzo, Caltanissetta passed to the latter, who, however, died of the plague in the vicinity of Catania in 1348; his son Federigo also died of the plague in 1355.[24] Caltanissetta was spared from the plague epidemic because of its territorial isolation, but the death of the feudal lords brought problems of succession: due to the Salic law in force, neither Cesarea nor her daughter Eleanor could inherit the city as women, and according to the provisions in case of a power vacuum in the fiefdoms, the city was to revert to the royal demesne. However, Cesarea succeeded in convincing the court and was allowed to continue to derive her livelihood from the fiefdom, despite the contrary sentiment of the population, which rose up several times in anti-feudal riots that finally forced the lady to leave the city in 1360, although she remained its ruler.[25]

In 1361, Frederick IV of Sicily and his bride Constance, after marrying in Catania, stopped by the castle of Pietrarossa to receive the nobles who wished to pay them homage, but were attacked by Francesco Ventimiglia and Federico Chiaramonte, rebellious nobles who refused to submit to the new king. A siege ensued in which the king, barricaded in the unconquerable castle, prevailed, despite numerous losses.[25]

In those years Eleanor, daughter of John of Randazzo, had married Guglielmo Peralta, who became the lord of Caltanissetta. In 1371 they founded a convent for the Carmelites, in a hermitage site outside the walls known as "Olive Grove," which coincides with today's Piazza Garibaldi; the convent, built next to the pre-existing church of St. James, was endowed with a church named after St. Mary of the Annunciation; in their place stands the Carmine Palace. Also probably contemporary are the church of Santa Domenica and the Magistrate's palace, both of which have disappeared.[26]

Meanwhile, Caltanissetta found itself at the center of international politics: during the early stages of the reign of the young Maria of Sicily, to avert coups by the Aragonese Dynasty, Guglielmo Peralta assembled precisely in Caltanissetta the so-called government of the Four Vicars, consisting of the most powerful men of the time (in addition to Peralta, Artale Alagona, Manfredi III Chiaramonte, Francesco II Ventimiglia), who divided up the whole of Sicily; the only major outsider was William Raymond III Moncada, who for that reason in 1379 kidnapped Queen Maria and took her to Spain, removing her from the control of Artale Alagona, her guardian.[27] This action favored the Aragonese monarchy: in 1391 Maria went in marriage to Martin the Younger, son of Martin of Aragon, strengthening Aragonese power over Sicily, and the following year they landed on the island, ending the rule of the Vicars. The legitimacy of the marriage, however, was not immediately accepted by all the nobles; among them Guglielmo Peralta, who remained entrenched in his castle.[28] The situation was not normalized until after Guglielmo's death in 1396, when his son Nicolò Peralta swore allegiance to the king. Nicolò died without male heirs after only two years, and his estates once again returned to the hands of his mother Eleanor, who administered them until her death in 1405.[28]

The Moncadas

[edit]

The arrival of the Moncadas

[edit]Upon the death of Eleanor of Aragon, the absence of direct heirs caused a dispute over possessions that ended with the temporary forfeiture of the properties to the Royal Treasury. The county of Caltanissetta was assigned to Sancho Ruiz de Lihori, a man loyal to the king, but he returned it after two years in exchange for more land and money. Caltanissetta was thus in the direct hands of King Martin I when in 1407 the Count of Agosta Matteo Moncada, the son of William Raymond, who was the architect of the kidnapping of Queen Maria, exchanged his fiefdom for Caltanissetta. The reasons for the exchange were probably economic and political, as Agosta (present-day Augusta) was exposed to pirate raids.[29] Caltanissetta therefore passed to the Moncada family, to whom it belonged until the abolition of feudality in Sicily in 1812; given the enormous power that feudal lords held and exercised in their own lands, the history of Caltanissetta during the 405 years of Moncada rule was closely influenced by their family affairs.

The 15th century

[edit]In the years when Matteo Moncada became the first count of Caltanissetta, a power vacuum was being created in Sicily by the deaths of Martin the Younger and Martin II of Sicily, both of whom had no male heirs. The nobles then split into two factions, one siding with Bernard Cabrera, the other with Blanche of Navarre, Martin the Younger's wife but illegitimate heir as a woman. Matteo Moncada actively supported Blanche of Navarre, so much so that he hosted her at the castle of Pietrarossa, a place where he and his family had settled after his appointment as count.[30][31]

Matteo Moncada died in 1423 in Canicattì, trying to escape an epidemic that had broken out in Caltanissetta,[32] and his successor became his son, William Raymond IV Moncada. When the latter died in 1465, having had no sons, the inheritance passed to his brother Antonio II Moncada, formerly a Dominican, who had to leave the religious habit to avoid dynastic disputes. Dating from this period is the first document attesting to the presence of the convent of San Domenico, probably built precisely at the same time as the future Count Antonio took the Dominican habit; it was in the crypt of that church that Antonio was buried when he died in 1479, as were all the Moncada counts for about a century to come. Due to the young age of Antonio's sons, he was succeeded by his cousin Giovanni Tommaso Moncada,[33] who increased his power over the territory and succeeded in obtaining the right to appoint abbots of Santo Spirito, which was previously a royal right.[34]

In the second half of the century a small Jewish community of about fifty individuals lived in Caltanissetta, which was affected by Spanish anti-Semitic policies. Many nobles of the time tried to persuade the Spanish king to exempt the Sicilian territory from the Alhambra Decree, which required Jews to undergo forced conversion on pain of confiscation of property and expulsion from the kingdom; among them was the Count of Caltanissetta Giovanni Tommaso Moncada, who was aware that the economic activities carried out by the Jews were indispensable and irreplaceable. Nevertheless, the decree was also implemented in Sicily; in Caltanissetta all Jews converted and were allowed to stay, but at least two cases of Marranism were found, a father and a son who were discovered and imprisoned at the Castello a Mare in Palermo, where they died.[35]

Spanish religious policies continued to influence the island: the Spanish Inquisition was introduced in Sicily in 1487,[36] and was not abolished until the 18th century. The last two Sicilian victims of the inquisition were the Caltanissetta friar Romualdo and Sister Gertrude, who were condemned to the stake on the night of April 6-7, 1725.[37]

In 1501 Giovanni Tommaso Moncada died and his son William Raymond became count. In 1507 the Franciscans arrived and founded their convent outside the walls. When William Raymond died in 1510, his son Antonio III Moncada succeeded him.[38]

The birth of the Caltanissetta bourgeoisie

[edit]Around the second half of the 15th century, aided by a population increase that brought the population to 4,000, the first embryo of the urban bourgeoisie emerged, made up of the leading economic operators of the time who had managed to accumulate wealth and often educate themselves; the Moncadas recognized its political, as well as economic, weight by entrusting it with the management of the city through bodies consisting of magistrates, jurors and judges chosen from the city's middle class, whose terms of office lasted one year. The functions of these bodies were essentially symbolic, the members were entitled to a very humble annual stipend, and they had to belong to the mastra nobile, a list of people considered suitable for a management role. The mastra nobile was subject to the approval of the count, who could revoke a member's appointment at any time; thus, within their own lands, the feudal lords continued to hold strong control of executive power, as well as legislative and judicial, and in certain cases, even religious, power, but the middle class would gain increasing powers, and this constituted the first step toward emancipation from the nobility.[34]

The growing economic and social power of the middle class, inadequately balanced by political power, led as early as 1516 to the first clash with the Moncadas. The protagonist was the notary Antonino Naso, who managed to coalesce the city's middle class in order to rebel against the feudal power, and succeeded in gaining the support of the population, which was suffering the effects of a severe famine; an insurrection broke out in June, and Naso and his loyalists took the opportunity to ask the viceroy to transfer Caltanissetta to the royal demesne, and drive out the Moncadas for good. However, the "bourgeois front" split, and the more moderate entered into a "separate peace" with the count, which stipulated that he could not appoint foreign officers, as had been the custom up to that time, but that they should be chosen from a shortlist of people from Caltanissetta expressed by the middle class; the event therefore resulted in a great success for the moderate bourgeoisie. The citizens nevertheless paid the count 3,500 salme (an ancient Sicilian unit of measurement) of grain as reparations,[39] while the extremists were tried and deprived of their property, except for Antonino Naso, who fled to Castrogiovanni, a state-owned town in which Moncada had no power.[40]

A few decades later, in 1548, in order to settle a dispute with the count, the middle class promoted the establishment of a civic council in which all those of age participated; nominally the council was an expression of the habitatores, or the people, but in fact it became an instrument in the hands of the bourgeoisie, which was able to influence it, much more than the nobility did.[41]

The 16th century

[edit]During the 16th century, the city's face changed, driven by constant population growth: in a short time, the population went from 6900 in 1570 to 9000 in 1586. The increase in population made it necessary to build an aqueduct, the Vagno, to supplement the traditional method of collecting water by means of large cisterns, which could no longer meet the city's needs. In 1550, the Monte di Pietà was founded, a sort of hospice for orphans and beggars, which in 1576[42] was enlarged and turned into a hospital. To cope with the growth in the volume of grain produced, the Capodarso bridge was built in 1553, which facilitated its transport to the ports on the southern coast.[43] During the century, the Benedictine monastery of Santa Croce (1531) and the Capuchin convent in the Xiboli district (1540) were also built; in the Plain of Olives in the early years of the century the church of San Sebastiano was built, and in 1539 construction work began on the church of Santa Maria la Nova, which became the mother church in 1570.[44]

After Antonio III Moncada, they were succeeded by Francesco I (1549-1566), Cesare (1566-1571) and Francesco II (1571-1592). Prominent figures were Aloisia de Luna and Maria of Aragon, consorts of Cesare and Francesco II respectively. The former is remembered for her great charity: she restructured the hospital and invited the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of Saint John of God, known as "Fatebenefratelli", to the city, and in order to encourage the education of all social classes she called the Jesuits who built their College; in 1580 she promoted and financed the transfer of the Capuchins to the new convent in Contrada Pigni;[45] she died in Palermo in 1619, after about forty years of rule over Caltanissetta and the other Moncada estates.[46] Maria is credited with the construction of the Benedictine monastery of Santa Flavia, founded in memory of her husband Francesco II, who died prematurely in 1592 at the age of 23.[47]

On the night of 27 February[48] 1567 due to a geological event, probably a landslide, a large part of the castle of Pietrarossa collapsed. The Moncadas no longer lived there from the beginning of the 16th century, as it was no longer suited to the lifestyle of the time, preferring a residence in an unspecified place in the Canalicchio area,[49] at the time outside the town centre, but which in the intentions of the counts was to be the new hub of the city. In fact, the first houses were built in the new quarters to the west of the original nucleus, including Annunciata, San Francesco and the Zingari.[50] In the second half of the century they moved again, to a palace with a rich garden, opposite the site where the future cathedral was being built.

In the wake of the never-ending Turkish invasion, the urban militia was established in Caltanissetta in 1554, consisting of 83 men, 30 of whom were knights. These were ordinary citizens in possession of a weapon who continued to carry out their day-to-day work, except at gatherings and in the event of war or siege. In reality, the Caltanissetta militia, also known as the Maestranza, never had to go into battle, and with time the military function faded, while retaining the civil function, attending the main religious festivals and parading on Holy Wednesday.[51]

The 17th century and the removal of the Moncadas

[edit]

The 17th century began with the arrival of the Reformed Friars Minor, who, at the behest of Aloisia in 1601, settled in the church of Santa Maria la Vetere and built a convent there out of the rubble of the castle of Pietrarossa.[52] The construction of new churches and convents continued throughout the century: in 1614 the churches of St Joseph and Madonna dell'Arco were built,[53] in 1626 the convent of the Discalced Augustinians attached to the church of Santa Maria della Grazia,[54] in 1637 the church of St Antony with the convent of the Reformed Friars Minor.[55] The religious spirit of the century is also testified by numerous miraculous and supernatural events recorded in those years; in particular, in 1625 St Michael was proclaimed patron saint of the city following the vision of the Capuchin friar Francesco Giarratana on 8 May of that year, who saw the archangel in a dream, preventing a plague victim from entering the city, whose body was actually found a few days later in a cave in the place where the church and convent of St Michael stand today.[52]

During the century, the demographic increase (in 1630 there were 10,600 inhabitants, almost twice as many as in 1570)[56] was matched by the foundation of new villages through the granting of licentiae populandi, which were supposed to increase cereal production by bringing peasants closer to the fields further away from the city. In this period, Delia (1597), Santa Caterina Villarmosa (1605), San Cataldo (1608), Resuttano (1625), Montedoro (1635) and Serradifalco (1640) were founded;[57] the demographic increase also affected the countryside closer to Caltanissetta, where from then on new hamlets were born, some on pre-existing farmsteads, others newly founded: Examples are Favarella, Prestianni, Santa Rita, Canicassè and Cozzo di Naro.[58] However, this was not enough to prevent famines from becoming increasingly frequent and reaching their peak in the winter of 1647-48, during which at least 1685 people died of starvation.[57]

On the death of Francesco II in 1592, the earldom had passed to Antonio d'Aragona Moncada, who had great political power in the Sicilian parliament thanks to his numerous possessions; However, in 1627 he had decided to follow a religious vocation, entering the Jesuit order,[46] and had left his possessions to his thirteen-year-old son, Luis Guillermo I Moncada, who, between 1635 and 1638 held the office of President of the Kingdom;[56] it is in this period that the construction of the Moncada Palace was begun.[59] Following the failure of an anti-Spanish conspiracy in Sicily, Count Luis Guillermo was called to Spain by King Philip IV to hold the post of viceroy of the kingdom of Valencia, so that around the second half of the century, the Moncadas effectively abandoned Caltanissetta, as evidenced by the interruption of the construction of their palace.[60] The sudden departure of the Moncadas had a twofold effect: on the one hand it impoverished the humblest strata of the population, which were already in misery due to famine and the taxes imposed by the crown, because the costs of maintaining the count and his family became ever greater;[57] on the other hand it favoured the rise of the bourgeois class, which went on to fill the void left by the Moncadas, who, due to the continuous need for money, sold vast tracts of land to the notables of Caltanissetta who began to become landowners.[61]

Battle of Caltanissetta

[edit]

Following the Peace of Utrecht in 1713, which had ended four centuries of Spanish rule, Sicily had passed to the Savoys, who were soon perceived as greedy bureaucrats and foreign invaders. In 1718, the Spaniards attempted to reconquer the island, involving Sicilians disillusioned by the Savoy. In this hostile climate, the viceroy of Sicily, the Piedmontese Annibale Maffei, left Palermo on his way to Syracuse to try to resist the Spaniards; on the way, he informed the jurors of Caltanissetta that he would stop there on 8 July with his troops for supplies and rest. At the same time, the jurors received an opposite order from the Spanish troops, asking them to show loyalty to the Spanish king by preventing Maffei's passage. Eventually, the jurors sided with the Spaniards and prevented Maffei's entry into the city with arms. Despite repeated requests, Maffei was forced to camp in the countryside with his troops. The next day, 9 July, Maffei's men managed to outflank the Caltanissetta militia, who had barricaded themselves in the convent of Our Lady of Grace, located at the main entrance to the city, by entering from the south and setting up camp near the Capuchin convent. They marched through the streets of the city without encountering resistance, starting to loot the houses, but the sudden violent death of Baron Faverges, who was following Maffei, and the approach of the Spanish troops, prompted the Piedmontese, short of ammunition and therefore unable to fight, to make peace with the inhabitants of Caltanissetta: After the troops of Piedmont left for Messina, aware that they could not get the better of the Spaniards, the battle ended with a toll of 53 victims from Caltanissetta and about twenty from Piedmont.[62]

Struggles for the 'reinstatement to the state property' of the city

[edit]In the second half of the 18th century, following a hereditary dispute that led to the investiture as count of Francesco Rodrigo Moncada, the local bourgeoisie waged a long legal battle to transfer the city to the direct jurisdiction of the king ('regio demanio') and put an end to the feudal rule of the Moncadas, but more than a struggle between the subordinate classes, it was an attempt by the local notabilities to institutionalise a situation that saw them take the place of the feudal lord in the management of the city, so much so that the bourgeoisie never opposed the feudal system in force. The dispute began in 1752, when a report was sent to the Court of the Royal Patrimony, signed by the Neapolitan jurist Francesco Peccheneda (under whose name was probably hidden Luciano Aurelio Barrile from Caltanissetta) and countersigned by members of the city's most illustrious families, presenting a city with a glorious past and numerous virtues, which would bring economic benefits to the kingdom and raise the prestige of the king; however, the process was blocked due to the bureaucracy and the influence of Prince Moncada. About thirty years later, the next generation of the same families that had countersigned Peccheneda's document promoted the reopening of the trial with the drafting of new documents that essentially reiterated the same motivations as thirty years earlier, but this second phase also failed. The dispute was not finally concluded until 1812, with the suppression of feudality throughout the kingdom of Sicily.[63]

Goethe's stay

[edit]

In 1787, the German playwright Wolfgang Goethe made a brief stopover in Caltanissetta during his trip to Italy. His stay in the city lasted only a day, and he made a brief account of it in his essay Italian Journey, published a few years later.

Goethe arrived in Sicily by ship from Naples, disembarked in Palermo on 2 April and, after reaching Girgenti, decided not to proceed along the coastal route, which would have led him to Syracuse, but to detour inland, eager to see for himself the vast cereal fields that had earned the island the title of granary of Italy since Roman times. His expectations were more than fulfilled, as his account shows:[64]

At last we are able to understand how Sicily gained the honourable title of the Granary of Italy. Shortly after leaving Girgenti, the fertile district commenced. It does not consist of a single great plain, but of the sides of mountains and hills, gently inclined toward each other, everywhere planted with wheat or barley, which present to the eye an unbroken mass of vegetation. Every spot of earth suited to these crops is so put to use and so jealously looked after, that not a tree is anywhere to be seen. Indeed, the little villages and farmhouses all lie on the ridges of the hills, where a row of limestone rocks (which often appear on the surface) renders the ground unfit for tillage. [...] And so our wish was gratified—even to satiety. We almost wished for the winged car of Triptolemus to escape from the monotony of the scene.

On 28 April, he then arrived in Caltanissetta, where he struggled to find suitable accommodation and was forced to borrow a kitchen from an elderly villager; the description of his experience[64] shows how, at the time, the city was almost isolated from the rest of the world, and its population lived on the edge of subsistence:[65]

After a long drive under the hot sun, through this wilderness of fertility, we were glad enough when, at last, we reached the well-situated and well-built Caltanisetta; where, however, we had again to look in vain for a tolerable inn. The mules are housed in fine vaulted stables; the grooms sleep on the heaps of clover which are intended for the animals' food; but the stranger has to look out for and to prepare his own lodging. If, by chance, he can hire a room, it has first of all to be swept out and cleaned. Stools or chairs, there are none; the only seats to be had are low little forms of hard wood; tables are not to be thought of.

If you wish to convert these forms into a bedstead, you must send to a joiner, and hire as many planks as you want. [...] But, above all things, provision must be made for your meals. On our road we had bought a fowl: our vetturino ran off to purchase some rice, salt, and spice. As, however, he had never been here before, he was for a long time in a perplexity for a place to cook our meal in, as in the post-house itself there was no possibility of doing it. At last an old man of the town agreed for a fair recompense to provide us with a hearth, together with fuel, and cooking and table utensils. While our dinner was cooking, he undertook to guide us round the town, and finally to the market-house, where the principal inhabitants, after the ancient fashion, met to talk together, and also to hear what we or other strangers might say.

We were obliged to talk to them of Frederick the Second; and their interest in this great king was such that we thought it advisable to keep back the fact of his death, lest our being the bearers of such untoward news should render us unwelcome to our hosts.

He left Caltanissetta the next day, heading for Castrogiovanni, and once again found himself in difficulty as he was unable to find a bridge that would allow him to cross the Salso river, and therefore had to ford it with the help of some men. The passage through the Sicilian hinterland was an altogether negative experience for the German poet and his fellow travellers, with whom, after spending an 'unpleasant night' in Castrogiovanni, he 'solemnly swore never again to choose a destination along the road just because of a mythical name'.[64]

19th century

[edit]From feudal city to capovalle

[edit]

In 1812, with the promulgation of the new Sicilian constitution at the instigation of the British, feudalism was abolished throughout the island. The old comarche were replaced by 23 districts, each one headed by a 'district capital' chosen from 'the most conspicuous populations and most favoured by local circumstances'.[66] Caltanissetta, despite its feudal past, was elevated to capital of its own district, but this was only the first step towards establishing itself as the main centre of the Sicilian hinterland. In 1817, a new administrative reform was introduced that provided for the suppression of the three historical valleys and the establishment of seven 'minor valleys', or provinces; Caltanissetta was elevated to "capovalle" of an all-new inland province, consisting of three districts (Caltanissetta, Piazza, Terranova) and twenty-eight municipalities. The 1817 reform recognised administrative autonomy to central Sicily and elevated Caltanissetta to the rank of the main Sicilian cities, including Palermo, Messina, Catania and Syracuse.[67]

The new role of capovalle city implied the presence of new institutional bodies: the reform of 1817 in fact provided that the capovalle cities were also capitals of the intendenza, and therefore the seat of the intendente (a figure with powers similar to those of the prefect) and of the Consiglio d'intendenza; closely related to the institution of the intendenza, the Consiglio provinciale was also established, presided over by the intendente himself and made up of fifteen members, and a provincial archive. Another novelty resulting from the administrative reform was the establishment of the municipality, at the head of which was placed a mayor assisted by the first elected and the second elected; the mayor presided over the decurionate, in fact today's municipal council. The first intendant of Caltanissetta was Antonino Di Sangiuliano, and the first mayor was Baron Mauro Calafato. In 1819 the city was affected by the reform of the judicial system, which established the Civil Court and the Grand Criminal Court, to be housed in the same building;[68] Mauro Tumminelli, who had supported Caltanissetta's candidature as capovalle city, was appointed president of the court, which in Caltanissetta also had jurisdiction over commercial disputes.[69] After four centuries of feudal rule, the real estate of the state property in Caltanissetta was scarce, and the sudden demand for many buildings to house as many institutions was not easy to satisfy; the intendant himself had to appoint a substitute while waiting for a suitable seat to be found for the intendance.[68]

The increased importance of Caltanissetta within the state landscape is also demonstrated in the measure passed by King Ferdinand I in 1824, which, as part of the rationalisation of administrative bodies, reorganised the island into four provinces headed respectively by Palermo, Messina, Catania and Caltanissetta; Caltanissetta was to be recognised as the central city for the whole of central-southern Sicily, through the annexation of the entire territory of the province of Girgenti; this reform was opposed by the parties involved, in particular Syracuse and Girgenti, which would be deprived of their administrative role, so much so that it was withdrawn in 1825, following the death of Ferdinand I, before being promulgated. Another reform project saw the light in 1828, which provided for the suppression of the province of Girgenti, in favour once again of the province of Caltanissetta, to which the districts of Girgenti and Bivona would be transferred, while the district of Sciacca would be assigned to the province of Trapani. This measure was also withdrawn following Girgenti's strong protests.[67]

In 1844, the city completed its institutional framework by becoming an episcopal see, with the creation of the diocese of Caltanissetta from the diocese of Girgenti. The issue had already been raised before the Neapolitan parliament a few years earlier by the deputy Giuseppe Cinnirella, who was strongly committed to resolving the apparent contradiction that saw Piazza as the seat of its own diocese, but administratively subordinate to Caltanissetta, which in turn was ecclesiastically subordinate to Girgenti.[67]

In barely thirty years, Caltanissetta had been transformed from a large feudal centre into an important institutional pole with administrative, judicial and religious organs, sanctioning the transition from an agricultural city owned by the Moncadas to an industrial city of worldwide importance in the mining sector.

Rolling roads connected it to Piazza Armerina, Barrafranca and Canicattì as early as 1838, but the railway did not arrive until 1878, with the opening of the railway station and the construction of Via Cavour, which was to connect the station to the city centre. In 1867 gas lighting arrived, and in 1914 the arrival of electricity allowed the first cinema to open.

However, the city was struck by cholera in 1837 and then twice more (1854 and 1866).

The events of 1820, the year of murder

[edit]

In the summer of 1820 Carbonarist uprisings broke out in Naples and Palermo, which Ferdinand I's granting of a new constitution based on that of Cadiz failed to quell. The popular uprising in Palermo led to the creation of a separatist government that aimed at the restoration of the Kingdom of Sicily (suppressed following the fusion with the Kingdom of Naples), and for this reason refused to ratify the constitution. Palermo's independentist aims, however, were not shared by the other Sicilian cities, and only Girgenti supported the initiative. Palermo's need to receive the support of the entire island led the Provisional Council to force its hand, forcing the larger centres to support the revolt. Eyes were particularly focused on Caltanissetta, a large centre in the militarily unprotected hinterland, where the moderate attitude of the mayor Angelo Rizzo had prevailed: he had posters announcing the promulgation of the constitution put up, and in the following days all the officials swore allegiance to it.[70]

Prince Salvatore Galletti of Fiumesalato made himself available to lead an uprising against Caltanissetta, backed by the fact that the seat of his noble title was in nearby San Cataldo, where he settled as early as 7 August to enlist men from the countryside and nearby towns with the promise of loot.[71]

The moderate and loyalist behaviour of the Caltanissetta elite was dictated by the concern that they would lose the privileges they had obtained as a result of the elevation to capovalle only a few years earlier. These fears were confirmed by the conditions dictated by the Sancataldese for the stipulation of surrender: among other things, they demanded the abolition of the intendancy, the Civil Court and the Grand Criminal Court, i.e. all those institutions granted to the city by the Bourbons. However, while the negotiations were still in progress, a group of armed citizens from Caltanissetta engaged in a clash against Galletti's troops posted on Mount Babbaurra, halfway between Caltanissetta and San Cataldo, achieving a short-lived victory. In the eyes of the San Cataldo people, the armed aggression appeared as a betrayal, which is why Galletti started military operations.[71]

After recapturing Babbaurra's positions, the attackers headed towards the convent of Madonna delle Grazie, at the entrance to Caltanissetta, where the resistance had barricaded itself in; by the evening of 12 August[72] anyone inside was killed, and the revolutionary troops had free access to the city, which was sacked and devastated for two days. The guerrilla, made up not of professional soldiers, but of poor people attracted by the hope of loot, who were joined by other people from neighbouring towns, soon ceased to respond to the commands of Prince Galletti, who was forced to send an armed group from Naro to the city to restore order, and to set up a provisional junta. In the following days, cannons were positioned on Mount San Giuliano and aimed at the city, with the intention of razing it to the ground, but on 7 September, the arrival of Bourbon troops led by General Costa put the rioters to flight and ended the violence.[71]

The uprising, besides causing considerable material damage, had cost the lives of 45 people, so much so that 1820 was remembered as 'the year of murder';[72] the news of the violence perpetrated against Caltanissetta spread quickly and many Sicilian cities rushed to send aid. With the repression of the uprisings throughout the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, no less than 1313 defendants were put on trial for the Caltanissetta events, although only the instigators of the revolt were condemned, including Prince Galletti himself, who had in the meantime gone into hiding, while the material perpetrators of the plundering were released with the amnesty and pardon of 1825. In the same year, the new King Francis I granted the city the title of fedelissima in recognition of its loyalty to the kingdom. In spite of everything, the events of 1820 caused wounds that did not heal for a long time; the decurionate, in order to give work to the humbler strata of the population, initiated a series of public works, including the reconstruction of the statues of the royals, destroyed by the rebels, and the creation of a new public garden, today's Villa Amedeo.[70]

The Sicilian Revolution of 1848

[edit]The city joined the revolutionary and independence movements of 1848-1849, led by Ruggero Settimo, which ended in Caltanissetta, where the capitulation of the revolutionaries was signed.

Expedition of the Thousand and the Unification of Italy

[edit]

The news of the landing of the Thousand at Marsala also had consequences in Caltanissetta. To ward off a popular uprising, the army was deployed in the centre of the city, and in the days leading up to the taking of Palermo, the army of about five thousand men of General Gaetano Afan de Rivera was also stationed there. Popular enthusiasm, already timidly manifested on the occasion of the establishment of Garibaldi's dictatorship by an unknown person who hoisted the tricolour on the ruins of the castle of Pietrarossa, exploded in the insurrection of 26 May, the day before the outbreak of the Palermo insurrection, when the troops left the city and all the old Bourbon institutions were declared to have fallen.[73]

On 17 June 1860, the new civic council of Caltanissetta, presided over by Vincenzo Minichelli, resolved to annex the city to the Kingdom of Italy; at the same time, the change of name of the city's main square, Piazza Ferdinandea, was established, which was named after Garibaldi. The following 29 June, the citizens clamoured to supplement the resolution of the civic council with the popular signature of the document. On the same evening, the signatures of 1064 notables from Caltanissetta were collected, thus expressing their consent to the annexation.[74][75]

Garibaldi's columns led by Hungarian colonel Ferdinand Eber arrived in Caltanissetta on 2 July 1860, preceded the day before by a vanguard corps. As Mulè Bertolo recounts, they were welcomed by all strata of the festive population, from peasants to the highest civil and military authorities. The Garibaldini entered the city, parading under a triumphal arch carpeted with tricolour flags and surmounted by a portrait of Victor Emmanuel, set up near the Santa Lucia gate. Along with the Garibaldini, the writer Alexandre Dumas also arrived in the city, who was hosted with Colonel Eber in the palace of Baron Francesco Morillo di Trabonella. During his stay in Caltanissetta, Dumas was granted honorary citizenship: bowing before the statue of the patron saint, St Michael, he said: 'St Michael, I am a citizen of Caltanissetta, take me under your protection'. On 7 July, a party was held at Villa Amedeo, which the young Cesare Abba described as a 'fairy party'. However, little more than two thousand people went to vote at the plebiscite on 21 October 1860, who almost unanimously confirmed their adherence to the new unitary state.[76]

Garibaldi returned to Sicily in 1862 and from 10 to 13 June he stationed in Caltanissetta, welcomed by the festive populace as two years earlier, to convince young men to enlist in order to conquer Rome and complete the Unification of Italy. Garibaldi's return rekindled, albeit momentarily, the enthusiasm and hopes that had already faded in the months following Garibaldi's first passage, when many of the Sicilian problems were not solved, but rather new ones were added, including the introduction of compulsory military service.[73]

Sulfur capital of the world

[edit]After the Unification of Italy, the city was affected by a great economic boom due mainly to intense mining activity, which, however, was often accompanied by various disasters: on April 27, 1867, 47 people died from a firedamp explosion in the Trabonella mine, 65 miners lost their lives at Gessolungo on November 12, 1881, also due to an explosion, and 51 others in 1911 at Deliella and Trabonella.

Gaetani, Testasecca and Lo Piano

[edit]

In the last decades of the century, Caltanissetta's political life was dominated by two important figures: Berengario Gaetani d'Oriseo (who was mayor from 1891 to 1894 and then from 1897 to 1911, himself the son of Mayor Giuseppe Gaetani d'Oriseo) and Ignazio Testasecca, an important mining entrepreneur who was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for eight consecutive terms in the Caltanissetta constituency.[77] During Gaetani's term of office, numerous public works were carried out, such as the widening of the road leading to the Capuchin Convent, which was named after Queen Margherita, while Testasecca donated half a million liras for the construction of a charitable hospice in the Palmintelli district, named after him, which earned him the title of count granted to him by King Umberto I by motu proprio.[78] Another prominent political figure was that of lawyer Agostino Lo Piano Pomar, who was a leader of the Caltanissetta section of the Fasci Siciliani and then in 1905 one of the founders of the Caltanissetta Chamber of Labor, which grew out of the social justice claims of the Caltanissetta miners.[79]

1900s

[edit]In 1920 local elections saw the victory of the social-reformist front, with the election of Agostino Lo Piano Pomar as mayor, which, however, produced numerous disturbances between the various political formations, some of which resulted in the killing of Gigino Gattuso, who would later be celebrated as a “fascist martyr.”[80] During World War II, between July 9 and 13, 1943, Caltanissetta was the scene of heavy bombardment by Anglo-American air forces as part of the Allied landing in Sicily, during which 350 civilians lost their lives. These events were anticipated by an air machine gunning that occurred in the city the night of June 17-18 earlier. Also, later that month, a German column was machine-gunned in the vicinity of the Capodarso Bridge. American troops landed in Licata on the morning of July 10, 1943 at 2:45 a.m. at Mollarella Beach with the 3rd Infantry Division and occupied the town on July 18.

A few months earlier, on March 21, 1943, a serious train accident affected a military train carrying 800 soldiers of the 476th Coastal Battalion from Castrofilippo to Termini Imerese, causing 137 deaths and 360 wounded.[81]

Gradually, Caltanissetta began to recover from the scars left behind by the war: in the 1950s restoration of the Cathedral, destroyed by U.S. Air Force bombing in 1943, began, and the streets had been cleared of rubble in previous years. On December 9, 1943, in the office of lawyer Giuseppe Alessi (the future first President of the Sicilian Region) in Via Cavour No. 19, a meeting took place in which Bernardo Mattarella, Salvatore Aldisio, Franco Restivo and many others participated and in which the founding of the Sicilian Christian Democracy was decided.[82]

Postwar period

[edit]

On the political level, no less than seven mayoral terms followed one another in the 1950s: Pietro Restivo (1948-52), Carmelo Longo (1952-54; 1954-56), Gioacchino Papa (1954), Ottavio Rizza (1956-57), Calogero Traina (1957-59) and Francesco Saverio D'Angelo (1959-61) succeeded one another at the helm of Palazzo del Carmine. These were almost always members of the Christian Democracy, with the exception of Gioacchino Papa, the first communist mayor of a Sicilian capital, albeit for a few months.[83] In these years, the municipality approved the town planning and reconstruction plan, one of the first in Italy, a document in which the new directions for building expansionism were foreseen: in it already appeared some fundamental arteries of the future modern part of the city, such as Via Palmintelli and Via Colajanni, as well as the presence of two new residential neighborhoods designed to accommodate the families of miners, the Santa Barbara village and the De Amicis neighborhood.[84]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]

The 1960s were not characterized by great economic splendor for the city, which continued to be primarily a land of emigration, just as it had been in previous decades. In fact, the city continued to live mainly on agriculture and sulfur mining, the latter already in full decline. In 1962, however, it was a source of pride and relief for the city's economy to inaugurate the first edition of the Central-Sicilian Fair exhibition, which continues to exist to the present day. The mayors succeeding each other during the decade were Calogero Traina (1961-62; 1965-67) and Umberto Traina (1962-65). In 1967, Piero Oberto was elected, who would later be swept up in some judicial investigations along with his predecessor Calogero Traina regarding his role in illegal construction, which would also lead him to prison.[84][85][86]

The 1970s began with the resignation, following threats received, of the newly elected mayor Raimondo Collodoro.[87] Collodoro was succeeded in the leadership of Palazzo del Carmine by, in order, Giuseppe Giliberto (1972-74; 1975; 1980-82), Giuseppe Sapia (1974-75), Vincenzo Assennato (1975-77) and Aldo Giarratano (1977-1980). Still at the end of the decade, outside of specific and organic urban planning regulations, new roads continued to be opened and entire residential areas were inaugurated, such as the Calcare, Balate and Pinzelli neighborhoods-dormitories (with the highly contested agglomeration of the so-called “Geraci plan”). In the course of the decade the city's roads were modernized: in 1971 the SS 640 Porto Empedocle (now renamed “Strada degli Scrittori”) expressway was inaugurated, which became the shortest link to Agrigento, in place of the old and winding SS 122 route. In 1973, however, the A 19 Palermo-Catania highway was inaugurated, an infrastructure of fundamental importance for all of central Sicily. Between 1976 and 1980, however, the city had to deal with more emergencies: initially with the typhoid and viral hepatitis epidemic, due to the poor condition of the water and sewage networks, and later with a 1979 regional law that closed most of the island's mines, which were now largely unproductive and in crisis.[84]

1980s and 1990s

[edit]

The 1980s were characterized by five mayoral terms: Giliberto was followed by Raimondo Maira, who would assume two terms (1982-84; 1988-90), also seeking agreement with the Communists, Salvatore Vizzini (1984-85), Silvestro Coco (1985), and Massimo Taglialavore (1985-88). During the decade, the City Council approved the first industrial master plan, to be followed by two others; the ASI Consortium could thus be born, with the decisive contribution of the Region. Shortly thereafter the Industrial Zone in the Calderaro district was inaugurated. Thus, building expansionism in Caltanissetta continued in this decade as well, leading to the creation of new residential areas; the city's methanization works were also undertaken and the privatization of the garbage collection service began. In 1979, after fifteen years of work, the new “Sant'Elia” hospital was inaugurated, replacing the old “Vittorio Emanuele II” hospital;[84] at the same time, the various municipal administrations that succeeded each other over time began the construction of numerous mid-level sports facilities, among which stands out the contract for the work, begun in 1982 and completed about ten years later, for the construction of the new sports field in Pian del Lago. Work on the electrification of the Palermo-Catania and Catania-Agrigento railway lines was also completed in May 1992.

The 1990s are considered to be among the darkest years for Caltanissetta: in addition to rampant unemployment,[88] the decade is characterized by the judiciary's investigation into illegal construction and collusion between the Mafia and politics called “Operation Leopard,” which stemmed from the statements of the Sancataldese pentito Leonardo Messina, and did not spare local politicians, entrepreneurs and public officials: a number of arrests were conducted, including those of well-known Caltanissetta construction entrepreneurs such as Francesco Cosentino, Pietro Di Vincenzo, Michele Biancucci and Santo Angilello, and even former mayor (who became a deputy) Rudy Maira, one of the city's most important political figures, was accused of being the political go-between with the gangs, charges that, however, would never find definitive confirmation.[89][90][91] Overwhelmed by allegations of collusion, the well-known criminal lawyer from Caltanissetta, Salvatore Montana, also committed suicide.[92] Involved in the scandal, in 1993 the Municipality of Caltanissetta, at the time led by Aldo Giarratano, was commissioned and entrusted to extraordinary commissioner Onofrio Zaccone. Just as the city was overwhelmed by the judicial scandal, however, it was honored by the visit of Pope John Paul II during his apostolic visit to Sicily. In 1993, the first local elections were held under the new electoral law inspired by the majority method: the elections were won by Peppino Mancuso, who would rule the municipality until 1997.[93] Mayor Mancuso is credited with a number of major public works and the inauguration of new sports facilities, the arrangement of Villa Cordova, the “garden of the city,” the repaving of the historic Via Palermo, and the upgrading of the sewage system of the new San Luca district, expanding in the southwestern suburbs and earmarked for housing cooperatives by the new 1999 master plan.[94] In the same period, CEFPAS, the permanent center for the training of health personnel, a facility of regional excellence that would become operational in 1996, was inaugurated.[95] In the same year in Caltanissetta, from the collaboration of the municipality, the province, some Sicilian universities and other public bodies, the University Consortium was established: shortly a number of degree programs in Medicine and Surgery, Education Sciences, Public Relations, Biology and Engineering were activated. In 1997, Michele Abbate triumphed in the local elections; the new mayor was responsible for the reopening, after a long ordeal, of the Teatro Margherita, just a year after the death of one of the founders of the Compagnia dello Stabile Nisseno, Giuseppe Nasca. The young mayor's experience would be very brief, however: in 1999 Caltanissetta achieved a national spotlight because of the fatal assassination of Abbate by a deranged man;[96] a few years after the heinous murder, Mayor Messana would dedicate the municipal cultural center to him. After the temporary entrustment of the municipality to Commissioner Stefano Agliata, who would launch the new master plan, elections in 1999 confirmed the victory of center-left candidate Salvatore Messana.[94]

2000s

[edit]

In 2002, the area known as “Terrapelata,” in Santa Barbara Village, was subject to a series of hydrogeological disruptions due to the “mud volcano” phenomenon. The emergency would reoccur even more intensely in the summer of 2008.[97] In 2004 Salvatore Messana won a second term, confirming himself as one of the longest-serving mayors of Caltanissetta. On the road system front, in 2006, work was finished on the completion of the Salso Valley state highway 626, a freeway: the artery thus made it possible to shorten travel time between Caltanissetta and Gela, the main center of the province. However, judicial investigations for alleged Mafia involvement would also arise on the contracting of these works.[98]

In 2009, work began on the upgrading to a freeway of State Road 640 in Porto Empedocle, which connects Agrigento to the Palermo-Catania highway via Caltanissetta.[99] Mayor Messana is credited with the conception, in 2008, of the urban redevelopment project for the historic center of Caltanissetta known as “The Big Square.” The project pursued the need to redevelop the two main arteries of the old city, Viale Vittorio Emanuele II and Corso Umberto, and Piazza Garibaldi: to this end, the strategic idea of pedestrianizing the entire historic center area was pursued with an increase in public transportation services, an increase in areas designated for parking for private vehicles, and a clear separation of pedestrian and vehicular areas.[100]

In 2009, Michele Campisi, supported by the center-right, was elected mayor. During the years of his mayoralty, work on the project The Big Square came into full swing, with the repaving of part of Corso Umberto (2012-2013).

In 2012, RAI announced the imminent dismantling of the city's transmitter and its 286-meter-high antenna, erected in 1954 and which had become one of the symbols of the city,[101] which Mayor Campisi tried to avert through the purchase, the procedure for which was never completed,[102] by the city administration of the entire facility and surrounding land.[103]

At the end of his term, Campisi did not run again; he was succeeded in 2014 by Giovanni Ruvolo, an independent supported by the center-left. Meanwhile, work continued on The Big Square project, with the repaving of Corso Vittorio Emanuele (2014-2015)[104][105] and the rehabilitation of the underground air raid shelter at Salita Matteotti, work on which began in 2015.[106] The gradual redevelopment of new areas as a result of these works prompted the Ruvolo administration to pursue policies aimed at limiting automobile traffic in the historic center through the permanent pedestrianization of Corso Umberto[107] and Piazza Garibaldi, and the establishment of the limited traffic zone in Corso Vittorio Emanuele,[108] which, however, rendered him unpopular among the merchants and residents of the affected areas,[109] so much so that a protest[110] prompted the mayor to replace the pedestrian island in Piazza Garibaldi with a LTZ limited to weekends.[111] At the same time, two symbolic places of the city of Caltanissetta closed their doors permanently: the Roman Café and the Sciascia bookstore, a result of the gradual abandonment of the historic center by commercial operators in favor of other newly built areas of the city.[112][113]

From May 15, 2019 began the term of Roberto Gambino, supported by the Five Star Movement, who was elected mayor after defeating center-right candidate Michele Giarratana in the runoff.

In 2022, the city became the head of the First World Park of the Mediterranean Lifestyle, a vast territorial development project that, through a community pact, manages to involve about 300 public, private and social partners existing in the territories of central Sicily.[114]

On May 12, 2022, the Region of Sicily enacted a law regulating the Park; with the same law in Article 6, the “Day of the Mediterranean Diet” was established.[115]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Caltanissetta | Caltanissetta, Italy | History & Culture | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ "Zone archeologiche > Gibil Habib". Piccola Atene. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 5-8.)

- ^ a b c d e Zaffuto Rovello (1991, pp. 11-27.)

- ^ a b c Zaffuto Rovello (1991, pp. 29–42).

- ^ Goffredo Malaterra. De rebus gestis Rogerii Calabriae et Siciliae comitis et Roberti Guiscardi ducis fratris eius (in Latin). Vol. IV libro. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ^ "Nevşehir Valiliği Çevre, Şehircilik ve İklim Değişikliği İl Müdürlüğü". Nevşehirin Tarihi (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2022-07-07. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ "NEVŞEHİR - Tarihçe". Coğrafya Dünyası. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Luigi Santagati - Castelli e Casali della Provincia di Caltanissetta. Ed. Paruzzo

- ^ Luigi Santagati (2009). "Nuove considerazioni sulla fondazione di Caltanissetta" (PDF). c. pp. 138 e succ.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2020). The concise Oxford dictionary of world place names: Caltanissetta. Oxford. OCLC 1202624108.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "São Gregório de Nissa". 12 March 2016.

- ^ "Gregory of Nyssa". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 7 May 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2022.

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 12-15.)

- ^ a b Santagati, 1989 & p. 47.

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello, 2008 & pp. 15-16.

- ^ Santagati, 1989 & p. 53.

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 16-17.)

- ^ Daniela Vullo; Alessandro Ferrara; Giuseppe Dell'Utri (2016). Daniela Vullo (ed.). Storia, architettura e restauro del complesso conventuale di Santa Maria degli Angeli a Caltanissetta. Caltanissetta: Paruzzo editore. pp. 11–26.

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 19-21.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, p. 22.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 25-26.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, p. 27.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, p. 30.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 30-33.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 56.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 33-35.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 36-37.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 39-40.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 58.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 40-41.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 61.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 42-43.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 43-45.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 45-46.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 47-50.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 86-88.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 51-52.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 64.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 52-54.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 54-56.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 66.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 59-61.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, pp. 64-65.)

- ^ Vitellaro, Antonio (January 2009). "Padre Girolamo da Caltanissetta, Camillo Genovese e la cultura a Caltanissetta nel Settecento". Archivio Nisseno (4). Caltanissetta: Società Nissena di Storia Patria: 84.

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 65-66.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 61-63.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 65.)

- ^ Between Garibaldi Square and Villa Cordova.

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 56-58.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 58-59.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 66-69.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 73.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, pp. 73-74.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 76.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 70-71.)

- ^ a b c Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 75-77.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, p. 74.)

- ^ Santagati (1989, pp. 75-76.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello, 2008 & pp. 77-78.

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, p. 73.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 82-86.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 93-96.)

- ^ a b c "Il viaggio in Sicilia di J. W. von Goethe" (PDF). Azioni Parallele. pp. 45–49. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Santagati (1989, pp. 87-89.)

- ^ Costituzione siciliana del 1812

- ^ a b c Torrisi (1997, pp. 21-36.)

- ^ a b Torrisi (1997, pp. 157-166.)

- ^ Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 97-100.)

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 100–107).

- ^ a b c "La guerra del 1820 vs Caltanissetta - Lorenzo Barone Web Site - UNREGISTERED VERSION". www.lorenzobarone.altervista.org. Retrieved 2024-07-07.

- ^ a b Giuseppe Saggio; Daniela Vullo (1998). Un giardino borbonico dell'Ottocento. Villa Isabella a Caltanissetta. Caltanissetta: Paruzzo. pp. 11–16.

- ^ a b Zaffuto Rovello (2008, pp. 135-137.)

- ^ Antonio Vitellaro (March 2011). "Campane, cavalli, muli e tela per la rivoluzione" (PDF). Il Fatto Nisseno. pp. 22–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "I Mille a Caltanissetta". Piccola Atene. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "L'Unità d'Italia a Caltanissetta". Piccola Atene. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Profilo di Ignazio Testasecca".

- ^ Alessandro Barrafranca (November 2011). "Testasecca, il sindaco filantropo diviso tra politica e beneficenza" (PDF). Il Fatto Nisseno. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ "Scioperi e rivendicazioni operaie degli zolfatari - Associazione Amici della Miniera - Caltanissetta". Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "Patrizio Gattuso lancia il guanto a Camilleri per l'avo Gigino - La Repubblica". 31 March 2005.

- ^ "La tragedia del treno dimenticata: il 21 marzo 1943 a Xirbi morti 137 militari, 360 i feriti". Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Siciliano coraggioso" (in Italian). February 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ "Il compagno Gioacchino Papa eletto sindaco di Caltanissetta" (PDF). l'Unità. 11 December 1954. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Michele Geraci (22 September 1977). "Tifo, ultimo atto dello sfascio" (PDF). L'Unità.

- ^ "Assolta in blocco la mafia di Caltanissetta" (PDF). Lotta Continua. 20 July 1972. p. 2.

- ^ "L' EX SINDACO ORDINO' L'ATTENTATO A PATANE' - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 16 December 1984. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "MINACCIATO DALLA MAFIA SI DIMETTE IL SINDACO D.C. Dl CALTANISSETTA" (PDF). L'Unità. 14 September 1972.

- ^ "QUI CALTANISSETTA 30 SU 100 A SPASSO - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 19 August 1993. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "INTERROGAZIONE A RISPOSTA SCRITTA 4/08035 presentata da PECORARO SCANIO ALFONSO (FEDERAZIONE DEI VERDI) in data 30/11/1992".

- ^ "COLPO MORTALE ALLA ' NUOVA MAFIA' - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 18 November 1992. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "DIECI ANNI DI MALAFFARE TRA VOTI E APPALTI COMPRATI - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 18 November 1992. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "GIU' DAL BALCONE L'AVVOCATO DEL BOSS - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 25 November 1992. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ "CALTANISSETTA, RIMONTA MSI SVANISCE IL SOGNO PROGRESSISTA - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 6 December 1993. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ a b "La strana crociata dell'ex procuratore - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 16 February 2000. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "LA MEGASCUOLA DEGLI SCANDALI - la Repubblica.it". Archivio - la Repubblica.it (in Italian). 12 March 1996. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "la Repubblica/fatti: Caltanissetta, il sindaco ucciso a coltellate". Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Regione Siciliana – Dipartimento della Protezione Civile. "Emergenza "Maccalube" dell'11 agosto 2008 nel comune di Caltanissetta – Descrizione dell'evento e dei danni" (PDF). pp. 1, 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-16. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ Alessandro Farruggia (22 May 2009). "Cede un giunto, il viadotto si spezza - È panico sulla Caltanissetta-Gela". Quotidiano.net. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Anas, Sicilia: cerimonia di posa della prima pietra dei lavori di realizzazione del primo tratto della Agrigento-Caltanissetta". 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "La Grande Piazza a Caltanissetta - Architetto Orazio La Monaca". Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ "E' vero: l'antenna di Caltanissetta sarà abbattuta". Portale Italradio. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "Caltanissetta. L'allarme di Giuseppe D'Antona: l'Antenna Rai potrebbe essere abbattuta". Il Fatto Nisseno. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Gioacchino Amato (12 November 2013). "Caltanissetta non abbatte l'antenna più alta d'Italia". Repubblica.it. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Corso Vittorio Emanuele, iniziano i lavori e le polemiche". AciNews. 8 September 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "I dissuasori in piazza, sono stati apposti i paletti in corso Vittorio Emanuele". TFN web. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Salvatore Mingoia (11 January 2015). "Caltanissetta: salita Matteotti rinascerà, aggiudicati i lavori". Giornale di Sicilia (Edizione Caltanissetta). Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Caltanissetta, isola pedonale nel centro storico: commercianti divisi fra favorevoli e contrari". 26 June 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Stefano Gallo (4 January 2016). "Caltanissetta, traffico in centro: via alla rivoluzione". Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Stefano Gallo (23 February 2016). "Ztl a Caltanissetta, esplode la protesta". Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Commercianti contro la ztl nel centro storico di Caltanissetta". Giornale di Sicilia (Edizione Caltanissetta). 23 January 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ Alberto Sardo (2 February 2016). "Il sindaco riapre al transito Piazza Garibaldi. Entro giugno arredo urbano e nuova illuminazione". Radio CL1. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ^ "Lettrice nissena: "Chiusura caffè Romano, conclama morte del centro storico. Potremmo trasformarlo in associazione culturale"". il Fatto Nisseno - Caltanissetta notizie, cronaca, attualità - cronaca, approfondimento e informazione nel nisseno (in Italian). Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Caltanissetta, una targa per ricordare la libreria Sciascia, cenacolo della "Piccola Atene"". la Repubblica (in Italian). 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.