HMS Beaulieu

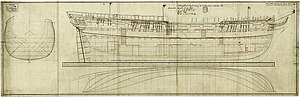

1790 diagram of Beaulieu

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Beaulieu |

| Namesake | Edward Hussey-Montagu, 1st Earl Beaulieu |

| Laid down | 1790 |

| Launched | 4 May 1791 |

| Completed | 31 May 1791 |

| Acquired | Purchased 16 June 1790 |

| Commissioned | January 1793 |

| Out of service | March/April 1806 |

| Nickname(s) | Bowly |

| Fate | Broken up 1809 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type | Fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen | 1,01979⁄94 (bm) |

| Length | |

| Beam | 39 ft 6 in (12 m) |

| Draught |

|

| Depth of hold | 15 ft 2+5⁄8 in (4.6 m) |

| Propulsion | Sails |

| Complement | 280 (274 from 1794) |

| Armament |

|

HMS Beaulieu (/ˈbjuːli/ BEW-lee)[2] was a 40-gun fifth-rate frigate of the Royal Navy. The ship was laid down in 1790 as a speculative build by the shipwright Henry Adams and purchased by the Royal Navy in June of the same year. Built to the dimensions of a merchant ship, Beaulieu was broader, with more storage capacity, than a standard frigate; though may not have had good sailing qualities. The frigate was commissioned in January 1793 by Lord Northesk and sent to serve on the Leeward Islands Station. She participated in the capture of Martinique in February 1794, and then was similarly present at the capture of the island of Saint Lucia in April. The frigate also took part in the initial stages of the invasion of Guadeloupe. Later in the year the ship's crew was beset by yellow fever and much depleted. Beaulieu was sent to serve on the North America Station to allow them to recuperate, returning to the Leeward Islands in 1795. In the following two years the ship found success in prizetaking and briefly took part in more operations at Saint Lucia. She returned to Britain at the end of 1796.

In 1797 Beaulieu joined the North Sea Fleet, in which she found herself part of the Nore mutiny. Her crew mutinied twice, once in May and once in June, but both attempts were defeated. Four members of the crew were executed for their participation. Beaulieu then fought at the Battle of Camperdown in October, unsuccessfully chasing the escaping Dutch ship of the line Brutus after the battle. After brief service in the Mediterranean Sea Beaulieu began to serve in the English Channel in 1800. By July of the following year she was a part of a frigate squadron based off Brest, France, and the boats of that squadron completed a cutting out expedition capturing the French corvette Chevrette in Camaret Bay.

Beaulieu was put in ordinary for the duration of the Peace of Amiens, but was brought back into service in 1804. The frigate was sent to serve in the Leeward Islands again, re-capturing one British merchant ship before returning home in 1806. She was paid off in March or April of that year, and sent to Deptford Dockyard where she was broken up in 1809.

Design and construction

[edit]

HMS Beaulieu was a 40-gun, 18-pounder, fifth-rate frigate.[3][4] Frigates were three-masted, full-rigged ships that carried their main battery on a single, continuous gun deck. They were smaller and faster than ships of the line and primarily intended for raiding, reconnaissance and messaging.[5][6] Beaulieu was designed and built by the shipwright Henry Adams at his shipyard, Buckler's Hard in Hampshire, during the peace between the American Revolutionary War and French Revolutionary War. There being a slump in ship construction between the wars, the ship was a private venture by Adams to ensure that his workmen were kept in employment.[7][8] She was the only 18-pounder frigate procured by the Royal Navy during this period and would continue to be a rarity; in 1793 she was one of only eight serving British frigates to have thirty-eight or more guns.[3][4][9]

Beaulieu was laid down some time in the first half of 1790, and was purchased by the Royal Navy on 16 June mid-way through construction, after an Admiralty Order was finalised on 2 June as part of the navy's reaction to the Spanish Armament that saw it begin to bolster the fleet.[10][11] The ship was named by Adams as a compliment to the local landowner Edward Hussey-Montagu, 1st Earl Beaulieu, and this name was kept on by the Royal Navy.[3][12] In service the crew nicknamed the ship "Bowly".[13]

Beaulieu was launched by Sir Harry Burrard on 4 May 1791.[14] The ship measured 143 feet 3 inches (43.7 m) along the upper deck, 122 feet 10+5⁄8 inches (37.5 m) at the keel, with a beam of 39 feet 6 inches (12 m) and a depth in the hold of 15 feet 2+5⁄8 inches (4.6 m). Her draught was 9 feet 5+1⁄2 inches (2.9 m) forward and 13 feet 9+1⁄2 inches (4.2 m) aft, with the ship measuring 1,01979⁄94 tons burthen. Beaulieu was fitted out to go in ordinary at Portsmouth Dockyard because the navy was on peacetime mobilisation levels, and this work was completed on 31 May. She stayed in ordinary until the French Revolutionary War began, and was finally fitted for sea on 14 March 1793.[10][11] Her construction and initial fittings cost a total of £17,788.[3]

While the ship was fitted out to Royal Navy standards after her purchase, the initial design had been down to Adams. As such, Beaulieu was not built in the slim fashion of other frigates, and was instead closer in proportion to a merchant ship of the period. This meant that her hold space was much greater than the average frigate, providing the capacity to store around double the amount of drinking water and ballast.[a] While no official report on Beaulieu's sailing survives, her unusual proportions have led the naval historian Robert Gardiner to suggest that it is "unlikely she was much of a sailer".[9]

Beaulieu held forty long guns.[10] The ship was internally laid out in the standard fashion for a 38-gun frigate, but with the addition of two extra gun ports.[9] Twenty-eight 18-pounders were held on the upper deck, with eight 9-pounders on the quarterdeck and a further four on the forecastle.[10] On 20 February 1793 an Admiralty Order had Beaulieu take on a number of carronades, with two 32-pounders on the upper deck and six 18-pounders on the quarterdeck. On 29 December six of the carronades were replaced with newer models, but they were all removed from the ship later on.[10][16] Beaulieu's upper deck had fifteen gun ports on each side, but only fourteen of these were ever put into regular use, with the final pair briefly holding the 1793 carronades but otherwise being left empty.[3]

The ship was designed with a crew complement of 280. On 12 December 1794 the Admiralty reorganised ship complements, taking into account the increased use of carronades, and Beaulieu's was lowered to 274 men.[10][17] This was because carronades were lighter than long guns and required a smaller gun crew to operate.[18] Many captains found this decrease unacceptable and frigate crews were often bolstered, although this is not recorded in Beaulieu's case.[17]

Service

[edit]West Indies

[edit]

Beaulieu was commissioned in January 1793 by Captain Lord Northesk, under whom she sailed to serve on the Leeward Islands Station on 22 April.[10] At a time when the Royal Navy was bolstering its forces against France and was looking to keep its most powerful frigates close to home, Gardiner posits that the Royal Navy chose not to keep Beaulieu there, although she was one of the larger frigates, because she was "never highly regarded".[9][19] By November Northesk had been replaced in command by Captain John Salisbury, and Beaulieu formed part of Vice-Admiral Sir John Jervis's Leeward Islands fleet; she then captured the French merchant ship America on 31 December.[10][20]

Jervis was undertaking a campaign to capture the valuable French-held islands in the West Indies, which accounted for a third of all French trade and supported (directly or indirectly) a fifth of the population.[21][22] The loss of the colonies would have a severe impact on the French economy.[23] On 2 February 1794 Beaulieu sailed from Bridgetown as part of an expedition containing 6,100 troops for the capture of Martinique. They arrived on 5 February and by 16 March all but two fortifications on the island had been successfully captured by the landing forces; seamen were used to move and operate gun batteries and mortars in the fighting.[24][25] Beaulieu received no casualties during the campaign.[26]

Beaulieu continued on with the expedition which arrived off Saint Lucia on 1 April.[10][27][28] The island surrendered on 4 April, and Jervis moved on to invade Guadeloupe, a campaign that would end unsuccessfully in December.[10][29] In November Salisbury handed command of the ship over to Captain Edward Riou, who brought with him several new officers because Beaulieu had taken severe losses from yellow fever in the previous three months.[10][30] Beaulieu was then sent to serve on the North America Station temporarily, so that her crew could recover from their illnesses and to bolster the station amid fears that a heavy squadron of French frigates was sailing for Newfoundland.[30][19]

On 2 December the frigate captured a fast-sailing French 10-gun privateer sloop, which was taken into the island of Barbados.[31] Beaulieu spent her time in North America patrolling off the coast of Virginia, before returning to the Leeward Islands, where she captured the French privateer schooner Spartiate on 14 April 1795.[10][30] Also under Riou, at an unknown date, Beaulieu encountered a French 18-gun store ship that had grounded herself earlier in the day under the protection of a battery near Saint-François. The frigate sailed up to the French vessel, and Lieutenant Bendall Robert Littlehales boarded her via Beaulieu's hawser. He attempted to dislodge the ship from her position, but she would not move, and so he took the crew as prisoners of war and set her on fire. For this Littlehales was promoted to serve in the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Majestic.[32]

Riou was invalided home and replaced by Captain Henry William Bayntun in September, and in turn Captain Francis Laforey took over from him in December of the same year.[10][33] This quick turnover of captains for Beaulieu continued into 1796; Captain Lancelot Skynner assumed command in March when Laforey was translated into the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Scipio.[10][34] The frigate, sailing with the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Ganges, captured the French 26-gun ship Marsouin on 11 March off Guadeloupe. Marsouin was later purchased by the Royal Navy but never commissioned for service.[10][20][35] With resistance and fighting on Saint Lucia having continued since the initial invasion, Beaulieu participated in further operations there. Towards the end of April the frigate was sent to support landings at Anse La Raye, but these were called off because of bad sea conditions. On 3 May the ship supported an attack by three columns of soldiers against two French batteries, but the endeavour was unsuccessful, and Beaulieu had three men wounded and her foremast damaged.[36]

Beaulieu arrived at the aftermath of an inconclusive duel between the 32-gun frigate HMS Mermaid and the French 40-gun frigate Vengeance off Basseterre on 8 August. Her presence forced the French vessel to disengage and retreat to safety under the guns of a battery in Basseterre Roads.[10][37] Towards the end of the year Beaulieu returned to Britain, carrying as passengers Rear-Admiral Sir Hugh Christian, who had been replaced as commander-in-chief of the Leeward Islands, and Rear-Admiral Charles Pole.[38][39]

Nore mutiny

[edit]Beaulieu received a refit at Plymouth Dockyard between December 1796 and February 1797, at the cost of £7,315.[10] The ship was then present at the capture of the Russian hoy Leyden and Fourcoing by the 18-gun brig-sloop HMS Harpy on 8 May, sharing in the capture with the 14-gun sloop HMS Savage.[40][41] Leyden and Fourcoing had been sailing with a cargo of madder, white lead, and smalt, from Rotterdam to Rouen.[42]

Beaulieu was serving as a guardship in the Downs in May, as part of the Downs Squadron. That month Admiral Adam Duncan's North Sea Fleet mutinied in the Nore mutiny. Despite not being with the fleet, Beaulieu's crew mutinied in support on 20 May alongside the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Overyssel.[43][44][45] This was instigated by the ship's boatswain, John Redhead, who had recently returned from sick leave, and was based on a feeling of "ill-use" with members of the crew feeling officers were punishing them cruelly for minor offences.[45][46][47] The two ships attempted to send petitioners to the Admiralty in London, demanding the removal of unpopular officers and a decrease in the use of flogging, but soldiers posted at Rochester blocked their route on 31 May.[48] Delegates from the mutinying Nore ships visited Beaulieu on 4 June, and it is likely that she conveyed them back to the Nore on the following day.[45][49]

Having sailed from the Nore, despite the authorities removing the marker buoys to make navigation out of the anchorage more difficult, off Margate on 11 June the mutinous members of Beaulieu were overpowered. Five escaped in a cutter but were caught when they landed in Kent on the following day. Five were also arrested on 15 June for having served as delegates of the crew during the mutiny.[45] The Admiralty pardoned all of the crew, bar the men arrested.[50] Soon after this Captain Francis Fayerman assumed command.[51]

In the aftermath two men remained imprisoned in the ship, and in order to release them the crew mutinied again on 25 June under Redhead.[52][51] He announced that his aim was "to turn every bastard of an officer on shore, and if any of the seamen were not true to the cause to hang them immediately".[53] Fayerman was on shore, and so Lieutenant John Burn received their demands for the release of the two men. Burn refused, and at 9 p.m. the men went to forcibly release their colleagues.[51] Burn armed his officers and marines and met the mutineers; after refusing a request to go back to bed, one of them ran at Burn with a cutlass. He was shot in the neck by the ship's purser and in the body by Burn.[54]

The mutineers made a second attempt to attack the officers and marines, stabbing one of them and attempting to gain control of more cutlasses. The defenders shot at them again, hitting two, and the survivors ran to Beaulieu's forecastle where they started turning her 9-pounders around to point back into the ship. Before they could fire Burn caught up with them again and all but one, who he shot in the shoulder, ran off. Burn then returned to the quarterdeck where he was attacked by one more mutineer, bruising his stomach with a cutlass. By 10:30 p.m. the mutiny had been quelled, and thirteen mutineers arrested. Thirteen men in total were wounded in the fight, of which at least one, the man shot by Burn and the purser, died.[54]

The loyal members of Beaulieu's crew were assisted in the fight by the 40-gun frigate HMS Virginie, which saw the incident and sailed up to her, providing thirty marines to assist and having her band play God Save the King.[55] Of the thirteen mutineers ten were brought to court martial. Four were executed, with another four imprisoned. Of the final two, one was flogged and the other given a lesser punishment.[56][57] Redhead was stripped of his warrant as a boatswain and sent back to sea as a common seaman.[58] Burn was awarded a silver-gilt presentation sword by the Committee of London Merchants for his "heroic conduct" during the mutiny.[59]

Camperdown

[edit]

News reached Duncan on 9 October that the French-aligned Dutch fleet was at sea, and his fleet sailed from Yarmouth Roads to meet them.[60] Beaulieu was already at sea, having been sent in advance with the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Russell and 50-gun fourth rate HMS Adamant to patrol off the Texel.[61] Duncan had them follow the Dutch, expecting that the fleet would attempt to sail towards the British coast.[62] At 7 a.m. on 11 October the three ships signalled a sighting of the enemy fleet to Duncan.[60][63] The Battle of Camperdown began at around 11:30 a.m., with Beaulieu one of only two British frigates present, alongside the 28-gun HMS Circe.[10][64][65] Tasked as a repeating frigate,[b] she was assigned to Duncan's larboard division of the fleet during the battle. The Dutch commander surrendered his ship at 3 p.m.[67][68][69] Beaulieu received no casualties while performing her duties.[63]

As the battle ended Beaulieu sailed up to the Dutch 44-gun frigate Monnikkendam, which surrendered to her.[70] A prize crew was put on board for the journey back to Britain under the command of Lieutenant James Robert Philips. While making this journey the frigate was wrecked on sands off West Capel.[71][72] Philips and his crew survived, but were all taken as prisoners of war.[72] After the battle bad sea conditions meant that many damaged warships were struggling to stay away from the shore, and Beaulieu was sent by Duncan to search out and assist any distressed ships that she could find.[68]

The 40-gun frigate HMS Endymion had joined the fleet after the battle, and on 12 October discovered the Dutch 74-gun ship of the line Brutus, which had escaped the battle, close to shore. Endymion attempted to attack her but with the Dutch ship well-positioned close to the coastline and the tide pulling Endymion into the line of her broadside, she chose to look for assistance. Endymion sailed back towards Duncan's fleet firing rockets to attract attention, and at 10:30 p.m. on 13 October these were spotted by Beaulieu.[73][71] Together the frigates returned to Brutus, arriving at 5 a.m. on the following day.[74] The two frigates chased the ship of the line, but she succeeded in reaching the safety of the port of Goree before they were able to engage her; Brutus was one of seven ships of the line to escape Camperdown.[73] Beaulieu was sent out again by Duncan to assist damaged ships on 15 October, in company with the 64-gun ship of the line HMS Lancaster.[75]

Having completed these duties, Beaulieu was subsequently sent to join a squadron commanded by Captain Sir Richard Strachan in 1798.[10] Strachan's squadron was employed in patrolling the coasts of Normandy and Brittany.[76] When the Irish Rebellion of 1798 began fears grew amongst officers that sailors would again take the opportunity to mutiny, and for a period officers in Beaulieu each kept two pistols in their cabin in case such an insurrection began.[77]

English Channel

[edit]On 1 June 1799 Fayerman sailed Beaulieu to the Mediterranean Sea, but by 10 August the ship had returned to home waters, serving in the English Channel.[10][78] She recaptured the British merchant brig Harriet on 3 December, and soon afterwards began serving with the 36-gun frigate HMS Amethyst. Together they recaptured the British merchant ships Cato, on 6 December; Dauphin, on 14 December; and Cabrus and Nymphe, on 15 December.[10][79][80] Continuing their spree of recaptures, the two frigates took the British merchant brig Jenny on 18 December.[80] Some time before 24 December Beaulieu also recaptured the American merchant ship Nonpareil.[81]

Beaulieu was sailing in company with the 18-gun sloop of war HMS Sylph on the morning of 27 August 1800 when they captured the French letter of marque sloop Dragon, which had been attempting to reach Bordeaux with a cargo of sugar, coffee, and cotton.[c][10][83] Beaulieu was then present at, but did not participate in, the capture of the French 16-gun privateer Diable á Quatre by the 32-gun frigate HMS Thames and 40-gun frigate HMS Immortalité off Cordouan Lighthouse on 26 October.[84][85] Still serving in the English Channel in 1801, on 1 January Fayerman was replaced by Captain Stephen Poyntz.[10][86]

Chevrette action

[edit]

By July Beaulieu was serving on the blockade of Brest, France, in a frigate squadron that also included the 36-gun HMS Doris and 40-gun HMS Uranie.[87] Sailing off Pointe Saint-Mathieu, the squadron discovered that the French 20-gun corvette Chevrette was at anchor in the nearby Camaret Bay, under the cover of a shore battery. The British decided to make an attempt to capture the corvette, and Admiral William Cornwallis sent out Lieutenant Woodley Losack from his flagship to undertake the cutting out expedition. With volunteer boat crews from Beaulieu and Doris under his command (Uranie having left the station), Losack set out on 20 July for Chevrette. While rowing for the bay the group of boats was split up, and some returned to the frigates instead of continuing. Unaware of this, the remaining boats waited until the morning of 21 July for the others, at which point the daylight revealed them to Chevrette, which began to prepare to defend herself.[88][89]

Chevrette sailed a mile closer to Brest, taking advantage of the protection of more gun batteries on shore, and brought on board a group of soldiers that increased her complement to 339 men.[90][89] The French also set up temporary fortifications along the coast, and set a small guard boat between the boats and Chevrette to warn the French of any advance by the British. Some time later in the day Uranie returned to the squadron and she added her manpower to the expedition, alongside that of two boats from the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Robust. This gave Losack a total force of 280 men in fifteen boats, with which he set out from Beaulieu for a second attempt at the bay at 9:30 p.m. Soon after this Losack took six of the boats in chase of a French lookout boat that was sailing close to the shore. With the element of surprise provided by the night dwindling as time went on, the senior officer of the remaining boats, Lieutenant Keith Maxwell of Beaulieu, continued the journey without Losack. This meant that the cutting out force now consisted of only 180 men. They arrived at Chevrette at 1 a.m. on 22 July, and the French ship began to fire at the boats with grape shot and muskets.[90][91][92] The boats containing Beaulieu's crew rowed up to the starboard side of the French vessel, with the remainders of the British force going to her port side.[93]

The French resisted the boarding in hand-to-hand fighting, by both attacking the British as they came aboard and by attempting in turn to board their boats.[94] Despite this, members of the British force succeeded in both cutting Chevrette's anchor cable and in setting her sails. After Maxwell's force had been on board Chevrette for three minutes, the ship began to drift out of the bay. A quartermaster from Beaulieu took control of the helm, and the remaining French defenders chose to either jump overboard or run below into the ship.[95] Those defenders hiding below deck began to fire up at the British with muskets, but they were forced to surrender upon the threat of them all being killed.[94][96] Chevrette resisted the fire of the French batteries on the coast and successfully left the bay. Here Losack joined the ship and took command. In the battle the British had lost eleven men killed, with a further fifty-seven wounded and one drowned when one of Beaulieu's boats was sunk by Chevrette.[95][10][91] Ninety-two Frenchmen were killed with sixty-two wounded.[97][98] Chevrette was taken to Plymouth, arriving on 26 July.[99]

The historian Noel Mostert describes the event, with its high casualties and zeal demonstrated by the British in pushing forwards with an attack that the French were fully prepared for, as "an episode without parallel".[96] Losack was promoted to commander for his part in the affair, but a controversy ensued when Maxwell was not also rewarded for his service despite having been the officer actually in command at the capture.[100] The letter published in the London Gazette outlining the action named Losack as the commander, and Maxwell wrote to Cornwallis explaining the unfairness of the situation. The admiral held a court of enquiry on board the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Mars to investigate Losack's conduct on 9 August. Both lieutenants were found to have behaved correctly, and Maxwell too was promoted.[100][101][102]

Later service

[edit]Beaulieu continued to serve in the Channel until the end of the French Revolutionary War.[103] With the Peace of Amiens coming into effect, she was put back in ordinary at Portsmouth in April 1802, and Poyntz left her in May.[10][86] The Peace having expired, she was fitted for service again between January and May 1804, being recommissioned by Captain Charles Ekins on 16 April.[d][10][105] Beaulieu sailed to again serve in the Leeward Islands in June, and in January 1805 she recaptured the merchant brig Peggy. Captain Kenneth Mackenzie replaced Ekins a month later when the latter was appointed to the 74-gun ship of the line HMS Defence.[10][106][105] Still serving in the Leeward Islands by October, the frigate returned to Britain some time after this and was paid off in March or April 1806. She was sent to Deptford Dockyard to be broken up on 3 June; this was completed some time during 1809.[10][11][107][108]

Prizes

[edit]| Date | Ship | Nationality | Type | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 December 1793 | America | Merchant vessel | Captured | [20] | |

| 2 December 1794 | Not recorded | 10-gun privateer sloop | Captured | [31] | |

| 14 April 1795 | Spartiate | Schooner | Captured | [10] | |

| Unknown date 1795 | Not recorded | 18-gun store ship | Destroyed | [32] | |

| 11 March 1796 | Marsouin | 26-gun ship | Captured | [10] | |

| 8 May 1797 | Leyden and Fourcoing | Merchant hoy | Captured | [40] | |

| 3 December 1799 | Harriet | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [80] | |

| 6 December 1799 | Cato | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 14 December 1799 | Dauphin | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 15 December 1799 | Cabrus | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 15 December 1799 | Nymphe | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [79] | |

| 18 December 1799 | Jenny | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [80] | |

| Before 24 December 1799 | Nonpareil | Merchant vessel | Recaptured | [81] | |

| 27 August 1800 | Dragon | Letter of marque sloop | Captured | [83] | |

| 26 October 1800 | Diable á Quatre | 16-gun privateer | Captured | [84] | |

| 21 July 1801 | Chevrette | 20-gun corvette | Captured | [10] | |

| January 1805 | Peggy | Merchant brig | Recaptured | [106] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ In 1800 this equated to 134 tons of iron ballast and 238 tons of shingle ballast, with 207 tons of water.[15]

- ^ Repeating frigates stationed out of the line of battle mirrored the flag signals sent out by their admirals so that messages could be more easily spread throughout the fleet.[66]

- ^ Dragon alternatively recorded as a cutter captured by Beaulieu and Sylph in September.[82]

- ^ Biographer John Marshall instead records that Ekins had been in command of Beaulieu since 1801.[104]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Winfield (2007), pp. 983–984.

- ^ "Beaulieu". Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Winfield (2007), p. 983.

- ^ a b Winfield (2007), p. 986.

- ^ "Frigate". Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ Gardiner (1999), p. 56.

- ^ Holland (2013), p. 284.

- ^ Wareham (1999), p. 30.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner (1994), p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Winfield (2007), p. 984.

- ^ a b c Gardiner (1994), p. 28.

- ^ Beaulieu's Figurehead (Sign in museum). Buckler's Hard, Hampshire: Buckler's Hard Maritime Museum.

- ^ Kennedy (1974), p. 100.

- ^ Holland (1985), p. 83.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 86.

- ^ Gardiner (1994), p. 102.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1994), p. 100.

- ^ Henry (2004), p. 17.

- ^ a b Gardiner (1999), p. 58.

- ^ a b c "No. 13972". The London Gazette. 17 January 1797. p. 57.

- ^ Marley (1998), p. 358.

- ^ Brown (2017), p. 45.

- ^ Howard (2015), p. 30.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 247.

- ^ James (1837a), p. 216.

- ^ Brown (2017), p. 226.

- ^ "No. 15976". The London Gazette. 18 November 1806. p. 1511.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 248.

- ^ Clowes (1899), pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c Marshall (1824), p. 284.

- ^ a b "No. 13751". The London Gazette. 10 February 1795. p. 147.

- ^ a b Marshall (1824), p. 285.

- ^ Nash (2008).

- ^ Marshall (1823b), p. 448.

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 611.

- ^ "No. 13903". The London Gazette. 21 June 1796. p. 593.

- ^ James (1837a), p. 341.

- ^ Clowes (1899), p. 293.

- ^ Marshall (1823d), p. 864.

- ^ a b "No. 15268". The London Gazette. 17 June 1800. p. 698.

- ^ "No. 15252". The London Gazette. 26 April 1800. p. 409.

- ^ "To be Sold by Auction". Kentish Weekly Post. No. 1956. Canterbury. 23 October 1798. p. 1. Retrieved 15 November 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), p. 171.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Brown (2006), p. 69.

- ^ Brown (2006), p. 74.

- ^ Hechter, Pfaff & Underwood (2016), p. 172.

- ^ Coats & MacDougall (2011), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Brown (2006), p. 60.

- ^ Dugan (1965), p. 363.

- ^ a b c Holland (1985), p. 128.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 508.

- ^ Glasco (2001), pp. 508–509.

- ^ a b Holland (1985), p. 129.

- ^ Marshall (1828), p. 249.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 559.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 563.

- ^ Glasco (2001), p. 509.

- ^ Nickel (1991), p. 39.

- ^ a b Allen (1852a), p. 458.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 191.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 198.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 326.

- ^ Winfield (2008), p. 32.

- ^ Allen (1852a), p. 459.

- ^ Lavery (1989), p. 262.

- ^ Allen (1852a), p. 461.

- ^ a b "No. 14055". The London Gazette. 16 October 1797. p. 987.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 212.

- ^ Jackson (1899), p. 304.

- ^ a b James (1837b), p. 77.

- ^ a b Marshall (1827), p. 252.

- ^ a b Willis (2013), p. 140.

- ^ James (1837b), p. 78.

- ^ Camperdown (1898), p. 214.

- ^ Laughton & Duffy (2008).

- ^ Wells (1986), p. 148.

- ^ Ward (1979), p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e "No. 15242". The London Gazette. 25 March 1800. p. 303.

- ^ a b c d "No. 15425". The London Gazette. 7 November 1801. p. 1341.

- ^ a b "No. 15221". The London Gazette. 11 January 1800. p. 38.

- ^ "No. 15335". The London Gazette. 7 February 1801. p. 164.

- ^ a b "No. 15294". The London Gazette. 16 September 1800. p. 1062.

- ^ a b "No. 15420". The London Gazette. 20 October 1801. p. 1284.

- ^ "No. 15308". The London Gazette. 4 November 1800. p. 1256.

- ^ a b O'Byrne (1849b), p. 921.

- ^ James (1837c), p. 148.

- ^ Allen (1852b), p. 50.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 539.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 51.

- ^ a b Clowes (1899), p. 540.

- ^ Morriss (2001), p. 137.

- ^ Allen (1852b), pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b James (1837c), p. 150.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 52.

- ^ a b Mostert (2007), p. 413.

- ^ Allen (1852b), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Ireland (2000), p. 164.

- ^ Mostert (2007), p. 414.

- ^ a b Allen (1852b), p. 53.

- ^ Cornwallis-West (1927), p. 361.

- ^ James (1837c), p. 152.

- ^ Marshall (1823c), p. 753.

- ^ Marshall (1823a), p. 766.

- ^ a b O'Byrne (1849a), p. 330.

- ^ a b "No. 15794". The London Gazette. 2 April 1805. p. 436.

- ^ Gardiner (2000), p. 188.

- ^ Tracy (2006), p. 134.

References

[edit]- Allen, Joseph (1852a). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 1. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 557527139.

- Allen, Joseph (1852b). Battles of the British Navy. Vol. 2. London: Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 557527139.

- Brown, Anthony G. (2006). "The Nore Mutiny – Sedition or Ships' Biscuits? A Reappraisal". The Mariner's Mirror. 92 (1): 60–74. doi:10.1080/00253359.2006.10656982.

- Brown, Steve (2017). By Fire and Bayonet: Grey's West Indies Campaign of 1794. Warwick: Helion. ISBN 978-1-915070-90-6.

- Camperdown, Earl of (1898). Admiral Duncan. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. OCLC 3472413.

- Clowes, William Laird (1899). The Royal Navy: A History from the Earliest Times to the Present. Vol. 4. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. OCLC 61913892.

- Coats, Ann Veronica; MacDougall, Philip (2011). The Naval Mutinies of 1797: Unity and Perseverance. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-669-8.

- Cornwallis-West, G. (1927). The Life and Letters of Admiral Cornwallis. London: Robert Holden & Co. OCLC 3195264.

- Dugan, James (1965). The Great Mutiny. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 711551.

- Gardiner, Robert (1994). The Heavy Frigate: Eighteen-Pounder Frigates. Vol. 1. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-627-2.

- Gardiner, Robert (1999). Warships of the Napoleonic Era. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-1171.

- Gardiner, Robert (2000). Frigates of the Napoleonic Wars. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-135-X.

- Glasco, Jeffrey Duane (2001). "We Are A Neglected Set", Masculinity, Mutiny, and Revolution in the Royal Navy of 1797 (PhD). Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Arizona. OCLC 248530588.

- Hechter, Michael; Pfaff, Steve; Underwood, Patrick (February 2016). "Grievances and the Genesis of Rebellion: Mutiny in the Royal Navy, 1740 to 1820". American Sociological Review. 81 (1): 165–189. doi:10.1177/0003122415618991.

- Henry, Chris (2004). Napoleonic Naval Armaments 1792-1815. Botley, Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-635-5.

- Holland, A. J. Holland (1985). Buckler's Hard: A Rural Shipbuilding Centre. Emsworth, Hampshire: Kenneth Mason. ISBN 0-85937-328-2.

- Holland, A. J. (2013). "The Beaulieu River: Its Rise and Fall as a Commercial Waterway". The Mariner's Mirror. 49 (4): 275–287. doi:10.1080/00253359.1963.10657744.

- Howard, Martin R. (2015). Death Before Glory! The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary & Napoleonic Wars. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-78159-341-7.

- Ireland, Bernard (2000). Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail: War at Sea 1756–1815. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-762906-0.

- Jackson, T. Sturges (1899). Logs of the Great Sea Fights 1794–1805. Vol. 1. London: Navy Records Society. OCLC 669068756.

- James, William (1837a). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 1. London: Richard Bentley. OCLC 963773425.

- James, William (1837b). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 2. London: Richard Bentley. OCLC 963773425.

- James, William (1837c). The Naval History of Great Britain. Vol. 3. London: Richard Bentley. OCLC 963773425.

- Kennedy, Don H. (1974). Ship Names: Origins and Usages during 45 Centuries. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0531-1.

- Laughton, J. K.; Duffy, Michael (2008). "Strachan, Sir Richard John, fourth baronet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lavery, Brian (1989). Nelson's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation 1793-1815. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-521-0.

- Marley, David F. (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Marshall, John (1823a). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 764–767.

- Marshall, John (1823b). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 446–449.

- Marshall, John (1823c). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 753–754.

- Marshall, John (1823d). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 1, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 86–93, 864.

- Marshall, John (1824). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. 2, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 283–289, 422–423.

- Marshall, John (1827). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 1. London: Longman and company. pp. 251–252.

- Marshall, John (1828). . Royal Naval Biography. Vol. sup, part 2. London: Longman and company. pp. 237–266.

- Morriss, Roger (2001). "The Channel and Ireland". In Robert Gardiner (ed.). Nelson against Napoleon: From the Nile to Copenhagen, 1798–1801. London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-3613.

- Mostert, Noel (2007). The Line Upon a Wind: An Intimate History of the Last and Greatest War Fought at Sea under Sail. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-06922-9.

- Nash, M. D. (2008). "Riou, Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Nickel, Helmut (1991). "Arms & Armors: From the Permanent Collection". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 49 (1): 1–63. doi:10.2307/3269006. JSTOR 3269006.

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849a). . A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. pp. 329–330.

- O'Byrne, William R. (1849b). . A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray. p. 921.

- Tracy, Nicholas (2006). Who's Who in Nelson's Navy: 200 Naval Heroes. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-244-3.

- Ward, S. G. P. (1979). "The Letters of Lieutenant Edmund Goodbehere, 18th Madras N.I., 1803–1809". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 57 (229): 3–19. JSTOR 44229429.

- Wareham, Thomas Nigel Ralph (1999). The Frigate Captains of the Royal Navy, 1793–1815 (PhD). Exeter: University of Exeter. OCLC 499135092.

- Wells, Roger (1986). Insurrection: The British Experience 1795–1803. Gloucester: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-303-2.

- Willis, Sam (2013). In the Hour of Victory: The Royal Navy at War in the Age of Nelson. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 9780857895707.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. London: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-78346-926-0.

External links

[edit] Media related to HMS Beaulieu (ship, 1791) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to HMS Beaulieu (ship, 1791) at Wikimedia Commons