Guo Huaiyi rebellion

| Guo Huaiyi rebellion 郭懷一事件 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

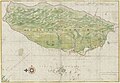

Map of Taiwan with Tainan shaded red | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Guo Huaiyi's peasant army |

Dutch East India Company Aboriginal Taiwanese | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000–15,000 |

1,000 Dutch soldiers 5,000 Formosan allies | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| c. 4,000 killed | 8 Dutchmen, unknown number of Formosan allies | ||||||

| Guo Huaiyi rebellion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 郭懷一事件 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郭怀一事件 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Guo Huaiyi rebellion (also romanized as Kuo Huai-i rebellion) was a peasant revolt by Chinese farmers against Dutch rule in Taiwan in 1652. Sparked by dissatisfaction with heavy Dutch taxation on them but not the aborigines and extortion by low-ranking Dutch officials and servicemen, the rebellion initially gained ground before being crushed by a coalition of Dutch soldiers and their aboriginal allies. It is considered the most important uprising against the Dutch during the 37-year period of their colonisation of Taiwan.

Background

[edit]The burden of Dutch taxes on the Chinese inhabitants of Taiwan was a source of much resentment. The falling price of venison, a chief export of the island at the time, hit licensed hunters hard, as the cost of the licenses was based on meat prices before the depreciation. The head tax (which only applied to the Chinese and not the aborigines) was also deeply unpopular, and thirdly, petty corruption amongst Dutch soldiers further angered the Chinese residents.[1]

Rebellion

[edit]The revolt was led by Guo Huaiyi (Chinese: 郭懷一; pinyin: Guō Huáiyī; Wade–Giles: Kuo1 Huai2-i1; 1603–1652), a sugarcane farmer and militia leader originally from Quanzhou known to the Dutch by the name Gouqua Faijit,[1] or Gouqua Faet.[2] He initially planned to start the insurrection on 17 September 1652, but after said plan was leaked to the Dutch authorities,[3] he decided to waste no time in attacking Fort Provintia, which at the time was only surrounded by a bamboo wall. On the night of 7 September, the rebels, mostly peasants-farmers armed with bamboo spears, stormed the fort.[1]

The following morning a company of 120 Dutch musketeers came to the rescue of their trapped countrymen, firing steadily into the besieging rebel forces and breaking them.[1] On 11 September the Dutch learned that the rebels had massed just north of the principal Dutch settlement of Tayouan. Sending a large force of Dutch soldiers and aboriginal warriors, they met the rebels that day in battle and emerged victorious, mainly because of the superior weaponry of the Europeans.[4]

Multiple aboriginal villages in frontier areas rebelled against the Dutch in the 1650s because of oppression, such as when the Dutch ordered aboriginal women for sex, deer pelts, and rice be given to them from aborigines in the Taipei basin in Wu-lao-wan village, which sparked a rebellion in December 1652 at the same time as the Chinese rebellion. The Wu-lao-wan beheaded two Dutch translators, and in a subsequent fight with 30 Wu-lao-wan two Dutch people died, but after an embargo of salt and iron the Wu-lao-wan were forced to sue for peace in February 1653.[5]

Aftermath

[edit]Over the following days, the remnants of Guo's army were either slaughtered by aboriginal warriors or melted back into the villages they came from, with Guo Huaiyi himself being shot, then decapitated, with his head displayed on a spike as a warning.[1] In total some 4,000 Chinese persons were killed during the five-day uprising, approximately 1 in 10 Chinese persons living in Taiwan at that time. The Dutch responded by reinforcing Fort Provintia (building brick walls instead of the previous bamboo fence) and by monitoring Chinese settlers more closely. However, they did not address the roots of the concerns which had caused the Chinese to rebel in the first place.[1]

However, the Taiwanese aboriginal tribes who were previously allied with the Dutch against the Chinese during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion in 1652 turned against the Dutch during the later siege of Fort Zeelandia and defected to Koxinga's Chinese forces after he offered them amnesty; they proceeded to work for the Chinese and behead Dutch people in executions.[6] The frontier aborigines in the mountains and plains also surrendered and defected to the Chinese on 17 May 1661, celebrating their freedom from compulsory education under Dutch rule by hunting down and beheading Dutch people and destroying their Christian school textbooks.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Andrade, Tonio (2005). "The Only Bees on Formosa That Give Honey". How Taiwan Became Chinese: Dutch, Spanish and Han Colonization in the Seventeenth Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12855-1.

- ^ Hsu, Hsueh-chi; Hsueh, Hua-yuan; Wu, Wen-hsing; Chang, Shu-ya, eds. (2004). 台灣歷史辭典 [Taiwan Historical Dictionary] (in Chinese). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Ministry of Culture. p. 3.

- ^ Vermeer, Eduard B. (1990). Development and Decline of Fukien Province in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Brill. p. 271. ISBN 978-90-04-09171-9.

- ^ Huber, Johannes (1990). "Chinese Settlers Against the Dutch East India Company: The Rebellion Led by Kuo Huai-i on Taiwan in 1652". In Vermeer, E.B (ed.). Development and Decline of Fukien Province in the 17th and 18th centuries. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004091719.

- ^ Shepherd 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Covell, Ralph R. (1998). Pentecost of the Hills in Taiwan: The Christian Faith Among the Original Inhabitants (illustrated ed.). Hope Publishing House. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0932727905. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Hsin-Hui, Chiu (2008). The Colonial 'civilizing Process' in Dutch Formosa: 1624–1662. Vol. 10 of TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction (illustrated ed.). Brill. p. 222. ISBN 978-9004165076. Retrieved 10 December 2014.