Kendrick Lamar

Kendrick Lamar | |

|---|---|

Lamar at the 2018 Pulitzer Prizes | |

| Born | Kendrick Lamar Duckworth June 17, 1987 Compton, California, U.S. |

| Other names | K.Dot |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 2003–present |

| Organization | PGLang |

| Works | |

| Partner | Whitney Alford (eng. 2015) |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Black Hippy |

| Website | oklama |

| Signature | |

| |

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth (born June 17, 1987) is an American rapper and songwriter. Regarded as one of the most influential hip hop artists of his generation, and one of the greatest rappers of all time, he is known for his technical artistry and complex songwriting. He was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first musician outside of the classical and jazz genres to be honored.

Lamar began releasing music under the stage name K.Dot while he was attending high school. He signed with Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE) in 2005, where he co-founded the hip hop supergroup Black Hippy. Following the success of his alternative rap debut album Section.80 (2011), Lamar secured a joint contract with Dr. Dre's Aftermath Entertainment and Interscope Records. He rose to prominence with his gangsta rap-influenced second album Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012), which became the longest-charting hip hop studio album in the Billboard 200's chart history. To Pimp a Butterfly (2015), Lamar's third album, embraced historical African-American music styles such as jazz and funk. It became his first of five consecutive number-one albums on the Billboard 200 chart, and was one of the most critically acclaimed albums of the 2010s.

In 2015, Lamar garnered his first number-one song on the Billboard Hot 100, after featuring on the remix of Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood". His critical and commercial success continued with his R&B and pop-leaning fourth album Damn (2017), yielding his second Hot 100 number-one single, "Humble". He curated original songs for the soundtrack album of the 2018 film Black Panther, earning a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Original Song for the US and UK top-ten single "All the Stars" (with SZA). Lamar's 2022 double album Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers concluded his tenure with TDE and Aftermath. His feud with Drake and sixth album GNX (2024) spawned the Hot 100 number-ones "Like That", "Not Like Us" and "Squabble Up".

Lamar has received various accolades throughout his career, including 17 Grammy Awards (the third-most won by a rapper), a Primetime Emmy Award, a Brit Award, four American Music Awards, six Billboard Music Awards, 11 MTV Video Music Awards (including two Video of the Year wins) and 37 BET Hip Hop Awards (the most won by any artist). Time listed him as one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2016. Two of his concert tours, the Damn Tour (2017–2018) and the Big Steppers Tour (2022–2024), are amongst the highest-grossing rap tours in history. Three of his works were included in Rolling Stone's 2020 revision of the 500 greatest albums of all time. Outside of music, Lamar co-founded the creative company PGLang and ventured into film with his creative partner, Dave Free.

Life and career

Early life

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth was born on June 17, 1987, in Compton, California.[1] He is the first child of former gang hustler Kenneth "Kenny" Duckworth and hairdresser Paula Oliver.[2] Both of his parents are African Americans from the South Side of Chicago.[2] When they were teenagers, they relocated to Compton in 1984, due to his father's affiliation with the Gangster Disciples.[3] Lamar was named after singer-songwriter Eddie Kendricks of the Temptations.[4] He was an only child until the age of seven and was described as a loner by his mother.[2][5] Eventually, his parents had his two younger brothers and younger sister, businesswoman Kayla Sawyer (née Duckworth).[6] His cousins include basketball player Nick Young and rapper Baby Keem.[7][8]

Lamar and his family lived in Section 8 housing, were reliant on welfare and food stamps, and experienced homelessness.[9][10] Although he is not a member of a particular gang, he grew up with close affiliates of the Westside Pirus.[3] Despite suffering hardships, Lamar remembered having "good memories" of his childhood that sparked his interest in hip hop music, such as sneaking into his parents' house parties.[2][11] He was raised secular, although he occasionally attended church services and was taught the Bible by his grandmother.[12] He felt "spiritually unsatisfied" as a child due to the "empty" and "one-sided" nature of the sermons.[13]

After hearing a recording of his voice for the first time, Lamar became interested in rapping.[14] He was introduced to police brutality after experiencing the first day of the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[2] When he was five years old, he witnessed a murder for the first time while sitting outside of his apartment unit, as a teenage drug dealer was killed in a drive-by shooting.[2] "It done [sic] something to me right then and there," Lamar later admitted to NPR Music. "It let me know that this is not only something that I'm looking at, but it's something that maybe I have to get used to."[15] His parents nicknamed him "Man-Man" due to his precocious behavior, although he confessed it "put a stigma on the idea of me reacting as a kid sometimes—I would hurt myself and they would expect me not to cry."[16]

In school, Lamar was a quiet and observant student who excelled academically and had a noticeable stutter.[17] His first grade teacher at Robert E. McNair Elementary School encouraged him to become a writer after she heard him correctly use the word "audacity".[18] As a seventh grade student at Vanguard Learning Center, Lamar was introduced to poetry by his English teacher, Regis Inge.[19] Inge integrated the literary form into his curriculum as a response to the growing racial tensions amongst his students.[19] Through its connection to hip hop, Lamar studied rhymes, metaphors and double entendres, which made him fall in love with songwriting: "You can put all your feelings down on a sheet of paper, and they'd make sense to you. I liked that."[2][19] Instead of completing assignments for other classes, Lamar would scribe lyrics in his notebooks.[19] His initial writing was entirely profane, but it helped him manage his psychological trauma and depression, which he struggled with during his adolescence.[19][20] Inge played a vital role in his intellectual growth, often critiquing his lexicon and suggesting prompts to strengthen his prose.[19]

Lamar later attended Centennial High School.[21] He was enrolled in summer school during the tenth grade, which he dreaded because it forced him to be embroiled in a gang war.[21] Despite his efforts to avoid them, Lamar soon became heavily involved with Compton's hedonistic gang culture, which led to numerous health scares and encounters with the police.[2] He distanced himself from the lifestyle following an intervention staged by his father.[5] When he was 16, Lamar was baptized and converted to Christianity following the death of a friend.[22][23] He graduated from high school in 2005 as a straight-A student.[24][25] He flirted with the idea of studying psychology and astronomy in college, but suspended his academic pursuits to focus on his music career.[2][26]

2003–2008: Career beginnings

During high school, Lamar adopted the stage name K.Dot and began freestyling and battle rapping at school.[1] His performances caught the attention of fellow student Dave Free, who traveled from Inglewood to watch him rap.[1] They quickly formed a friendship over their love of hip hop and the television sitcom Martin.[1] They recorded music together at Free's makeshift garage studio and at his older brother's Hyde Park apartment.[1] Lamar's earliest performances were held at a "super hood" comedy club and behind a tattoo parlor.[1] Free was his hype man during that time, while his older brother was his manager and disc jockey.[1] Lamar recorded five mixtapes throughout the 2000s; his first, Youngest Head Nigga in Charge (Hub City Threat: Minor of the Year), was released on April 15, 2003, through Konkrete Jungle Musik.[27] The mixtapes primarily consisted of freestyles over the production of popular hip hop songs.[27]

In a series of retrospective reviews for Rolling Stone, Mosi Reeves complimented Lamar's "unerring" sense of rhythm and timing found in Hub City Threat: Minor of the Year, but criticized his "clumsy" lyricism and that his flow was "overly beholden to ... Jay-Z and Lil Wayne".[27] Free, who was working as a computer technician, introduced the mixtape to record producer Anthony "Top Dawg" Tiffith while attempting to repair his computer.[28] Tiffith was impressed with Lamar's burgeoning abilities and invited him to partake in an audition process for entry into his newly established independent record label, Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE).[28] During his audition, Lamar freestyled for Tiffith and record executive Terrence "Punch" Henderson for two hours, a strategy that impressed Henderson but bewildered Tiffith.[5][29] He was offered a recording contract by TDE in 2005, joining Jay Rock as the label's first signings.[5] Upon signing, he purchased a minority stake in the label for an undisclosed amount.[29]

Lamar had a brief stint as a security guard when he started working on music with Jay Rock at TDE's in-house recording studio.[30][25] The bond he formed with him, Ab-Soul and Schoolboy Q led to the formation of the hip hop supergroup, Black Hippy.[31] Lamar released his second mixtape, Training Day, on December 30, 2005.[27] Reeves complimented its varied production and "well-executed" concept, which was based on the 2001 film of the same name.[27] In 2006, Lamar signed an artist development deal with Def Jam Recordings and was featured on two singles by the Game. He also heavily contributed to Jay Rock's first two mixtapes, Watts Finest Vol. 1 and Watts Finest Vol. 2: The Nickerson Files.[16][32] Lamar was ultimately let go from Def Jam after an encounter with its president and chief executive officer, Jay-Z; he later described it as "one of those situations where I wasn't ready."[33][34] Lamar and Jay Rock released a collaborative mixtape, title No Sleep 'til NYC, on December 24, 2007.[27] Reeves thought the project was a "fun cypher session, nothing more, nothing less."[27]

2009–2011: Overly Dedicated and Section.80

Lamar's third mixtape C4, released on January 30, 2009, is a tribute project to Lil Wayne's Tha Carter III (2008) and was supported by his co-sign.[35] Reeves felt that the mixtape was a "wrongheaded homage to a year-old, well-worn album."[27] From February to July, he toured with the Game on his LAX Tour as a hype man for Jay Rock.[36][37] Lamar disliked how his stage name diverted attention away from his true identity, and decided to retire it.[38] He opted to use his first and middle names professionally and regards the name change as part of his career growth."[39] For his eponymous debut extended play (2009),[40] Lamar eschewed the creative process of his mixtapes in favor of a project heavily focused on his songwriting over "lovely yet doleful" production.[27] Reeves described the EP as the "first standout project" of his career, praising its melancholic tone.[27] He felt that the project restored his reputation following the sting of criticism he received over C4.[27]

After striking a music publishing deal with Warner/Chappell Music,[41] Lamar released his fourth mixtape, Overly Dedicated, on September 14, 2010. It was his first project to be purchased through digital retailers.[42] Reeves described Overly Dedicated as a partial "victory lap" that marked a shift in his songwriting.[27] The mixtape peaked at number 72 on Billboard's Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart.[43] Lamar served as Jay Rock's hype man for a second time during Tech N9ne's Independent Grind Tour, where Overly Dedicated was introduced to Dr. Dre.[44][45] After watching the music video for the song "Ignorance Is Bliss" on YouTube, he reached out to Lamar with hopes of working with him and Snoop Dogg on his unfinished album, Detox.[44][46] He also considered signing him to his record label, Aftermath Entertainment, and was encouraged to by artists such as J. Cole.[47][48]

Lamar entered a brief relationship with Nitty Scott,[49][50] and was featured on XXL's 2011 Freshman Class list.[51] He released his debut studio album, Section.80, on July 2, 2011,[52] which was supported by its lead single "HiiiPower".[53] The album explored conscious and alternative hip hop styles and experimented with "stripped-down" jazz production.[54][55] Ogden Payne of Forbes considers it to be "the genesis to [Lamar] successfully balancing social commentary with mass appeal."[56] Section.80 marked Lamar's first appearance on the Billboard 200 chart, where it peaked at number 113. It sold approximately 5,000 copies in its first week of tracking, with minimal coverage from mainstream media outlets.[57] To promote the album, Lamar performed at small venues and college campuses across the U.S.[58][59] He was dubbed the "New King of the West Coast" by Snoop Dogg, Dr. Dre and the Game during a performance in West Los Angeles.[60][61] Throughout the year, he appeared on the Game's The R.E.D. Album, Tech N9ne's All 6's and 7's, 9th Wonder's The Wonder Years, and Drake's Take Care.[62]

2012–2013: Good Kid, M.A.A.D City

Lamar began planning his second album before Section.80 was released.[63] From February to April 2012, he opened for Drake on his Club Paradise Tour.[64] He began working with J. Cole on a collaborative album around that time.[65][66] On March 8, The Fader reported that Lamar had signed a joint venture recording contract with Aftermath Entertainment and Interscope Records; under the deal, TDE continued to serve as his primary label.[67] His first commercial single, "The Recipe" featuring Dr. Dre, premiered on rhythmic crossover radio on April 2.[68]

Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, Lamar's second album and first under a major record label, was released on October 22, 2012.[69][70] He worked with producers such as Pharrell Williams, Hit-Boy, Scoop DeVille, Jack Splash, and T-Minus to create an atmospheric West Coast hip hop album with heavy gangsta rap influences.[71] Its lead single, "Swimming Pools (Drank)",[72] marked Lamar's first top 20 single on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.[73] Its other singles, "Backseat Freestyle", "Poetic Justice", and "Bitch, Don't Kill My Vibe", enjoyed moderate commercial success.[74][75] Good Kid, M.A.A.D City was met with widespread critical acclaim, who lauded Lamar's nonlinear songwriting and thematic scope. Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune applauded him for giving gangsta tropes a "twist, or sometimes upend[ing] them completely" on a record that "brims with comedy, complexity and the many voices in [Lamar's] head."[76] The album debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 with 242,000 copies sold;[77] the highest first-week album sales of the year by a male rapper.[78] Good Kid, M.A.A.D City surpassed The Eminem Show (2002) to become the longest-charting hip hop studio album on the Billboard 200.[79] In October 2022, it became the first hip hop studio album to spend over ten consecutive years on the chart.[80]

From September to October 2012, Lamar headlined the BET Music Matters Tour with Black Hippy and Stalley.[81] He won Lyricist of the Year at the BET Hip Hop Awards,[82] and was featured on ASAP Rocky's single "Fuckin' Problems" alongside Drake and 2 Chainz, which reached the top 10 in the U.S.[83] Lamar embarked on two headlining concert tours in 2013: a national college tour with Steve Aoki and his first international tour.[84][85] He struggled with depression, survivor's guilt and suicidal ideation during promotional events upon learning of the deaths of three close friends.[86] From October to December 2013, Lamar opened for Kanye West on his Yeezus Tour, despite disapproval from his label and management team.[87][88] He was baptized for a second time during the beginning of the tour, and experienced a nervous breakdown near the end.[89][90] Lamar won three awards each during the BET Awards and BET Hip Hop Awards,[91][92] including Best New Artist at the former.[93][94]

Lamar was featured on six songs throughout the year: "YOLO" by the Lonely Island featuring Adam Levine,[95] the remix of "How Many Drinks?" by Miguel,[96] "Collard Greens" by Schoolboy Q,[97] "Control" with Big Sean and Jay Electronica,[98] "Give It 2 U" by Robin Thicke featuring 2 Chainz,[99] and "Love Game" by Eminem.[100] His performance on "Control" was described as a "wake up call" for the hip hop industry and commenced his decade-long feud with Drake.[101] Rolling Stone noted that his verse made the track one of the most important hip hop songs of the last decade.[102] Lamar was named Rapper of the Year by GQ during their annual Men of the Year edition.[103] Following the issue's release, Tiffith pulled him from performing at GQ's accompanying party and accused Steve Marsh's profile on him of containing "racial overtones".[104][105]

2014–2016: To Pimp a Butterfly and Untitled Unmastered

After his opening stint for the Yeezus Tour ended, Lamar started working on his third album.[88] He earned seven nominations at the 56th Annual Grammy Awards (January 2014), including Best New Artist, Best Rap Album, and Album of the Year for Good Kid, M.A.A.D City.[106] He was winless at the ceremony, which several media outlets felt was a snub.[107][108] Macklemore, who won Best New Artist and Best Rap Album, shared a text message that he sent Lamar after the ceremony ended, in which he apologized for winning over him.[109] The incident was the subject of widespread media attention, controversy and Internet memes.[110] During the awards ceremony, Lamar performed a mashup of "M.A.A.D City" and "Radioactive" with rock band Imagine Dragons, which was met with critical acclaim.[111][112]

Lamar opened for Eminem on the Rapture Tour from February to July 2014.[113][114] On August 9, he premiered the short film M.A.A.D, which he starred in, commissioned and produced, during the Sundance Institute's Next Fest.[115] He released "I" as the lead single to his third album, To Pimp a Butterfly, on September 23, which won Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song at the 57th Annual Grammy Awards.[116][117] His performance of "I" during his appearance as a musical guest on Saturday Night Live was lauded by contemporary critics.[118] Lamar was featured on three songs in 2014: "It's On Again" by Alicia Keys,[119] "Babylon" by SZA,[120] and "Never Catch Me" by Flying Lotus.[121] He won Lyricist of the Year for the second consecutive time at the BET Hip Hop Awards.[122]

Originally scheduled to arrive at a later date, To Pimp a Butterfly was released on March 15, 2015.[123] The album incorporated various genres synonymous with African American music, such as jazz, funk, and soul.[124] To capture its essence, Lamar recruited producers such as Sounwave, Pharrell Williams, Terrace Martin, and Thundercat.[125] Whitney Alford, Lamar's high school sweetheart, contributed background vocals on select tracks.[126] Other singles from the album were "The Blacker the Berry",[127] "King Kunta",[128] "Alright", and "These Walls"–all of which enjoyed moderate commercial success.[129] Selling 324,000 copies in its first week, To Pimp a Butterfly became Lamar's first number-one album on the Billboard 200 and the UK Albums Chart.[130][131] Billboard commented that "twenty years ago, a conscious rap record wouldn't have penetrated the mainstream in the way [Lamar] did with To Pimp a Butterfly. His sense of timing is impeccable. In the midst of rampant cases of police brutality and racial tension across America, he spews raw, aggressive bard while possible cutting a rug."[132] Pitchfork opined that the album "forced critics to think deeply about music."[133]

Lamar announced his engagement to Alford in April 2015.[134][135] He earned his first number-one single in the U.S. through the remix of singer-songwriter Taylor Swift's "Bad Blood".[136][137] It won Video of the Year and Best Collaboration at the MTV Video Music Awards, while the music video for "Alright" won Best Direction.[138] Lamar later re-recorded his featured appearance on the "Bad Blood" remix in support of Swift's counteraction to her masters dispute.[139][140] He opened the BET Awards with a controversial performance of "Alright" and won Best Male Hip Hop Artist.[141] He also won three awards at the BET Hip Hop Awards.[142] In support of To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar embarked on the Kunta's Groove Sessions Tour, which ran from October to November 2015 in select intimate venues across the U.S.[143] For his work on the album and other collaborations throughout the year, Lamar earned 11 nominations at the 58th Annual Grammy Awards, the most by a rapper in a single night.[144] He led the winners with five awards: To Pimp a Butterfly was named Best Rap Album, "Alright" won Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song, "These Walls" won Best Rap/Sung Performance, and "Bad Blood" won Best Music Video.[145]

During the ceremony, Lamar performed a critically acclaimed medley of "The Blacker the Berry", "Alright", and an untitled song.[146] He previously performed untitled songs on The Colbert Report (December 2014) and The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon (January 2016).[147][148] After receiving a request from basketball player LeBron James to share the untitled works, Lamar released his first compilation album, Untitled Unmastered, on March 4, 2016.[149] It contained eight untitled, dated, unfinished, and entirely self-written tracks that were intended to be included on To Pimp a Butterfly, and continued the album's exploration of jazz, funk, soul, and avant-garde styles.[150] Untitled Unmastered received critical acclaim and debuted atop the Billboard 200 with 178,000 album-equivalent units, becoming Lamar's second consecutive number-one project.[151] Throughout the year, he was featured on four commercially successful songs: Beyoncé's "Freedom",[152] Maroon 5's "Don't Wanna Know",[153][154] the Weeknd's "Sidewalks",[155] and Travis Scott's "Goosebumps".[156]

2017–2019: Damn and Black Panther: The Album

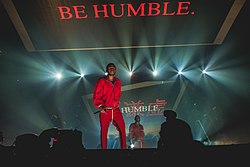

On March 1, 2017, during a cover story for T, Lamar confirmed that he was working on his fourth album, Damn.[157] He released the promotional single "The Heart Part 4" on March 23, before releasing the album's lead single "Humble" on March 30.[158][159] The song debuted at number two on the Hot 100 and reached the top spot in its second week of charting. It is Lamar's second single, and first as a lead artist, to top the chart.[160] Damn was released on April 14.[161] It utilized a more mainstream musical palette than To Pimp a Butterfly, exploring R&B and pop elements.[162] Rolling Stone described its sonics as a "brilliant combination of the timeless and the modern, the old school and the next-level."[163] Damn became Lamar's most commercially successful album. It spent four non-consecutive weeks atop the Billboard 200, marking his third consecutive number-one album, and debuted with 603,000 units sold.[164][165] All of the album's 14 songs debuted on the Hot 100, including the top-20 singles "Loyalty" and "Love".[166] Damn was the seventh best-selling album of 2017, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), while "Humble" was the sixth best-selling single of the year.[167] By June 2018, it became the first album by a rapper or solo artist to have every song featured earn a gold certification or higher from the Recording Industry Association of America.[168]

To support Damn, Lamar embarked on his first headlining arena tour, the Damn Tour, from July 2017 to July 2018.[169] It grossed $62.7 million in worldwide revenue, becoming one of the highest-grossing hip hop tours in history.[170] At the 2017 MTV Video Music Awards, Lamar opened the ceremony with a performance of "DNA" and "Humble".[171] He later won five awards, including Best Hip Hop Video, Best Direction, and Video of the Year for "Humble"; the latter win marked the first time an artist won the prize for a video they co-directed.[172][173] Throughout the year, he was featured on the remix to Future's "Mask Off",[174] SZA's "Doves in the Wind",[175][176] and Rich the Kid's "New Freezer".[177] He won Best Male Hip Hop Artist at the BET Awards,[178] while Damn won Favorite Rap/Hip Hop Album at the American Music Awards.[179] A collector's edition of the album, which featured its tracklist in reverse order, was released in December.[180][181]

On January 4, 2018, Lamar announced that he would be curating and executive producing Black Panther: The Album, the soundtrack from the 2018 film of the same name.[182] It was released on February 9 and was supported with three commercially successful singles: "All the Stars",[183] "King's Dead",[184] and "Pray for Me".[185][186] Lamar contributed lead and background vocals to every track on the album, regardless of credit, and produced on select songs.[187][188] Music critics consider Black Panther: The Album to be a milestone achievement, giving praise towards its lyrics and cultural significance.[189][190] It spent two consecutive weeks atop the Billboard 200,[191] and earned the most single-week streams for a soundtrack album in history.[192] Lamar opened the 60th Annual Grammy Awards with a critically acclaimed medley.[193] He won five awards during the ceremony: Damn was named Best Rap Album, "Humble" won Best Rap Performance, Best Rap Song, and Best Music Video and "Loyalty" won Best Rap/Sung Performance.[194] Damn won the Pulitzer Prize for Music on April 16, 2018, marking the first time a musical composition outside of the classical and jazz genres received the honor.[195][196]

From May to June 2018, Lamar co-headlined The Championship Tour with several TDE artists.[197][198] While on tour, he became embroiled in a public dispute with Spotify regarding the streaming service's Hate Content & Hateful Conduct policy.[199][200] Lamar was featured on five songs throughout the year: "Dedication" by Nipsey Hussle,[201][202] "Mona Lisa" by Lil Wayne,[203] "Tints" by Anderson .Paak,[204][205] and "Wow Freestyle" by Jay Rock; he also executive produced the latter's album Redemption.[206][207] At the American Music Awards, Black Panther: The Album won Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album.[208] Lamar made his acting debut as a drug addict in the crime drama series Power (2018).[209] After his two concert tours ended, he entered a four-year recording hiatus;[210] although he contributed to Beyoncé's The Lion King: The Gift, Schoolboy Q's Crash Talk, and Sir's Chasing Summer (all 2019).[211][212] As his publishing deal with Warner/Chappell Music was beginning to expire,[41] Lamar signed a long-term worldwide deal with Broadcast Music, Inc.[213] He and Whitney Alford welcomed their first child, Uzi, on July 26, 2019.[214][215]

2020–2023: Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers

On March 5, 2020, Lamar and Dave Free launched the creative entity PGLang, which was described at the time as a multilingual, artist-friendly service company.[216][217] In October, he signed a worldwide administration agreement with Universal Music Publishing Group.[218] Lamar announced through an August 2021 blog post that he was in the process of producing his final album under TDE, confirming rumors that emerged last year that he would be leaving to focus on PGLang.[219][220] The following week, he appeared on Baby Keem's single "Family Ties", which won Best Rap Performance at the 64th Annual Grammy Awards.[221][222] Lamar made additional contributions to Baby Keem's album The Melodic Blue by providing background vocals and appearing on the song "Range Brothers".[223] In November, he held a "theatrical exhibition of his musical eras" during his second headlining performance at Day N Vegas,[224][225] and featured on Terrace Martin's album Drones.[226] He co-headlined the Super Bowl LVI halftime show alongside Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Eminem, 50 Cent, and Mary J. Blige on February 13, 2022, which won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Variety Special (Live).[227][228]

After releasing the promotional single "The Heart Part 5",[229][230] Lamar's fifth album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, was released on May 13, 2022.[231] He and Alford used the album's cover art to announce the birth of their son, Enoch.[232][233] The double album drew on jazz, R&B, trap, and soul influences;[234][235] Alford served as its primary narrator.[236] It was widely acclaimed by critics, who applauded Lamar's vulnerable songwriting and scope.[237] Every track from the album charted on the Hot 100; its three singles–"N95", "Silent Hill", and "Die Hard"–debuted in the top-10.[238] Selling 295,000 units in its first week, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers became Lamar's fourth consecutive number-one album on the Billboard 200.[239] It later became the first hip hop album of the year to reach one billion streams on Spotify.[240]

In support of Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, Lamar embarked on the Big Steppers Tour, which ran from July 2022 to March 2024.[241] The tour grossed $110.9 million in worldwide revenue, becoming the highest-grossing rap tour ever at the time.[242] Lamar wrote, co-directed, and executive produced the short film adaptation of the song "We Cry Together", which was released worldwide in September 2022.[243] An accompanying concert film for the tour, Kendrick Lamar Live: The Big Steppers Tour, was released in November.[244][245] Lamar won Favorite Male Hip Hop Artist at the American Music Awards, and Favorite Hip Hop Album for Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. He received six awards at the BET Hip Hop Awards, including Album of the Year.[246][247] During the 65th Annual Grammy Awards, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers was named Best Rap Album, while "The Heart Part 5" won Best Rap Performance and Best Rap Song.[248]

In May 2023, Lamar was featured on the standalone version of Beyoncé's single "America Has a Problem" and appeared on Baby Keem's single "The Hillbillies".[249][250] He won four awards at the BET Hip Hop Awards, and set four records in the process.[251] Lamar was featured in the documentary concert film Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé and executive produced Baby Keem's short film adaptation of The Melodic Blue.[252][253] He quietly shedded his ties with Aftermath Entertainment and signed a new direct licensing agreement with Interscope.[254]

2024–present: Feud with Drake, GNX and Super Bowl LIX halftime show

Lamar's conflict with Drake re-escalated in March 2024 with his surprise appearance on Future and Metro Boomin's track "Like That".[255] The song spent three consecutive weeks atop the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Lamar's third number-one single and his first song to debut at the top spot.[256] From April to May, he released the Drake-aimed diss singles "Euphoria",[257] "6:16 in LA",[258] "Meet the Grahams",[259] and "Not Like Us"; all of which were either positively received or acclaimed by critics.[260] The latter installment marked the first rap song to lead the Hot 100 with a limited tracking week.[261] A celebratory one-off concert, titled The Pop Out: Ken & Friends, was held on Juneteenth.[262] On September 8, 2024, it was announced that Lamar would headline the Super Bowl LIX halftime show, marking the first time a rapper has led the performance as a solo act.[263] Three days later, he released an untitled song to his Instagram account.[264] On November 22, he shared a song titled "GNX", exclusively on YouTube, followed with a surprise release of the album of the same name on streaming the same day.[265][266]

Outside of music, Lamar starred in the animated biographical film Piece by Piece (2024).[267] He signed on to produce a comedy feature with Free, Trey Parker and Matt Stone for Paramount Pictures, which is slated to be released on July 4, 2025.[268]

Artistry

Influences

Tupac Shakur is Lamar's biggest influence, having impacted both his professional and personal lives.[269] One of his earliest childhood memories is watching him and Dr. Dre film the second music video for their single "California Love" with his father at the Compton Swap Meet.[11] Lamar has described himself as an "offspring" of Shakur's artistry and sociopolitical views.[270] Although some publications regard him as the Shakur of his generation,[271][272] he strives to maintain his individuality.[273]

Shakur's The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996), The Notorious B.I.G.'s Life After Death (1997), and DMX's It's Dark and Hell is Hot (1998) influenced Lamar's artistic direction: "I don't look at these albums like just music; it sounds like an actual film."[274] He also listened and took influence from Mos Def and Snoop Dogg during his childhood,[275] and said, "I wouldn't be here today if it wasn't for Eazy-E."[276] 50 Cent's mixtape success inspired Lamar to become an independent artist,[5] while his view on being categorized as a conscious rapper, "Yeah, I'm a conscious artist because I have a conscience," gave him a sense of perspective.[277]

Prodigy of Mobb Deep was a key influence on Lamar's earlier mixtapes,[278] while his rapping technique was stemmed from Lil Wayne and his longevity.[279] Eminem and his album The Marshall Mathers LP (2000) introduced him to songwriting elements, such as ad-libs, and impacted his aggressive approach to records such as "Backseat Freestyle".[280][281][282] He took inspiration from N.W.A's tenacity of representing his hometown with "courage, honesty and artistic brilliance."[283] Various R&B and soul artists, including Marvin Gaye,[284] the Isley Brothers,[284] Michael Jackson,[285] Teddy Pendergrass,[286] Sade, and Anita Baker, have influenced Lamar.[287] He performed with Prince, who impacted his vocal register,[288] at Paisley Park to celebrate the release of the latter's 2014 albums Plectrumelectrum and Art Official Age, which GQ described as "five minutes of brilliant insanity."[289] To Pimp a Butterfly was influenced by the works of jazz trumpeter Miles Davis and funk collective Parliament-Funkadelic.[290]

Musical style

The nature of Lamar's musical style has been described as "anti-flamboyant, interior and complex."[291] He is rooted in West Coast hip hop,[292] and has continually reinvented his sound by branching out into other genres.[293] Due to his contributions to its audience growth, through his appeal to mainstream listeners, music critics generally categorize Lamar as a progressive rap artist.[294] He suggests that his music is genreless, explaining in a 2012 interview, "You really can't categorize my music, it's human music."[295] PopDust opined that during the 2010s, a decade that was arguably defined by hip hop, Lamar constantly pushed the boundaries of what the genre could be.[296]

Lamar did not care for music production during the beginning of his career.[297] However, as he placed an emphasis on songwriting and "making material that's universal", he grew more exacting and adventurous with his compositions.[297] He is heavily involved with every aspect of his production process, including the mixing and mastering stages, and is known for working long hours in the recording studio.[298] "You gotta be hands on and know the different sounds and frequencies," Lamar explained to Variety.[297] "What makes people move, what melodies stick with you, taking the higher octaves and the lower octaves and learning how to intertwine that in a certain frequency, how to manipulate sound to your advantage."[297] Lamar chooses to work with a close-knit team of musicians, rather than constantly seek high-profile talent.[44] He has been working with his longtime producer, Sounwave, since his 2009 self-titled EP.[27]

Kendrick Lamar marked a pivotal change in Lamar's artistry. Unlike his earlier mixtapes, which consisted of freestyles over CHR and urban radio singles, the EP incorporated melancholic and "doleful" original production that emphasized his lyrics.[27] Austere jazz production was blended with alternative rap styles on Section.80,[299] with instrumentals drawing from R&B, boom bap, psychedelia, and downtempo.[300] Good Kid, M.A.A.D City abandoned the tastes of contemporary hip hop by exploring a subtle, atmospheric side of West Coast hip hop and gangsta rap.[301][302] To Pimp a Butterfly is an amalgamation of genres synonymous with African-American music, most prominently jazz, funk, and soul.[303][304] It redefined jazz rap by highlighting improvisation and soloing rather than primarily using sampling.[305][306] Minimalist arrangements are incorporated in Damn and Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers.[307][308] Damn appealed to mainstream listeners through its pop and R&B-influenced production,[309] while the scattered and distorted instrumentals of Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers was designed to make listeners feel anxious and uncomfortable.[310]

Voice

Several media outlets consider Lamar to be the greatest and most important rapper of his generation.[311][312] Billboard, Forbes and Vibe named him the second-greatest rapper of all time, behind Jay-Z.[313][314] Described as a "blazing" technical rapper and "relentless searcher" by The New York Times,[291] Lamar's "limber, dexterous" flow switches from derivative to generative metrics,[315][316] while incorporating internal and multisyllabic rhyme schemes.[317] His rhymes are typically manipulated within common time, allowing him to subtly control his metrical phonology and suggest formal ambiguities similar to pop and rock repertoires.[317] Some of his rhyme manipulations feature "flexible" new school styles evoking the 1990s, while others use "rigid" old school elements recalling the 1980s.[317] Lamar frequently uses syncopation in his melodies to create contradictions between his lyrical content and rhythms.[318] With Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, he liberally plays with pronunciation, inflections, and delivery to mirror the album's emotional range.[319]

Lamar possesses a versatile tenor vocal range[320][321] and a raspy, half-shout timbre, where "his throat sounds dry and his mouth sounds wet."[322] André 3000 was the first rapper that introduced him to singing sensibilities in hip hop,[323] and he writes melody-driven songs as practice for his albums.[323] Lamar became comfortable with his vocals over time, to the point where he feels confident enough to create singing-based albums.[324] Pitchfork noticed how his harmonies on To Pimp a Butterfly never made him sound alone throughout his "desolate" performance; comparing his vocal layering to "standing in the middle, unnoticed, of a large quarrelsome crowd."[325]

Praised for his willingness to use his voice as an instrument,[326] Lamar adopts different cadences, tones, modulations, and timbres to suggest conflicting personalities, paint distinct emotions, and communicate stories using characters and personas.[327][328] His falsetto register, which he calls the "ghetto falsetto",[323] has been likened to Curtis Mayfield's.[329] MTV writes that by manipulating his voice, Lamar calls back to a lineage that runs through James Brown's foundational work in the 1960s, 1970s psychedelia, Prince's "sweaty" phantasmagoria in the 1980s, and 1990s gangsta rap.[330] He was ranked the tenth-best solo singer of the 21st century by The Times in 2023.[331]

Songwriting

Branded as a "master of storytelling" by The New Yorker,[328] Lamar has been referred to as one of the greatest lyricists in modern hip hop by several publications and his peers.[332][333] Pharrell Williams suggests that what makes his songwriting stand out is because he "knows how to be very disciplined with a subject matter, he knows that stickiness is important, and he knows that it has to be great."[334] American Songwriter notes that for as much as Lamar is a musician, lyricist, and emcee, he is also "a playwright, a novelist, a short story author. He's literary within the art form of music."[335] Lamar's reflective narrative songwriting pulls from a wide range of literary and cinematic techniques, such as hip hop skits and voice-overs, to allow his audience to follow internal and external storylines.[336] His fusion of various film styles and his sonic influence has elevated his works to be some of the most "consistently poignant" in hip hop, and promoted the advancement of the narrative device.[336]

Lamar, who self-identifies as a musician and writer,[157] begins his songwriting process with an assortment of premeditated thoughts that he jotted down over the course of one year.[337] His personal experiences are a common source of inspiration, but he also pulls ideas from meeting new people, traveling, and experiencing different cultures.[337] A devout Christian, he additionally shares his spiritual triumphs and struggles on his songs.[338][339] He is an avid note-taker, and has developed keywords, phrases, and sounds to help him "trigger the exact emotions" he felt when writing the initial demo.[337] Considered to be a "radio-friendly but overtly political rapper" by Pitchfork,[340] and a populist by The Wall Street Journal,[341] Lamar's songwriting regularly infuses political criticism and social commentary concerning African-American culture.[342] Common themes explored include racial inequality, institutional discrimination, and black empowerment.[343] Lamar's critiques has been compared to the State of the Union Address by The Guardian,[344] while Billboard described it as "Shakespearean".[345] HuffPost opined that his work is a "great" piece of journalism because it "speaks from the prerogative of black communities facing oppression and directly attacks the institutions responsible for their pain," an achievement most reporters cannot attain.[346]

Lamar tries to carry a conceptual idea inside of his music, "whether it's a big concept or it's so subtle you can't even tell until you get to 20 listens."[297] Fans and publications have theorized that his albums are related to different forms of mass media.[347] Section.80 is regarded as a short story collection inspired and themed around events that impacted the millennial generation, such as Ronald Reagan's presidency.[348][349] The nonlinear narrative structure of Good Kid, M.A.A.D City is billed as a coming-of-age short film that chronicles Lamar's harsh teenage experiences in his native Compton.[350][351] Its cinematic scope has been compared to the screenplays written by filmmakers Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino.[352][353] To Pimp a Butterfly unfolds as both a poem and blank letter that explores the responsibilities of being a role model and documents life as an African American during Barack Obama's presidency.[354][355] Damn is labeled as an introspective satire that explores the dualities of human nature and morality.[356][357] Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers takes on the form of a theatrical play, with confessional lyrics based on Lamar's experiences in therapy.[358][359]

Reception

Legacy

As one of the most influential musicians of the 2010s decade, Lamar has been deemed a paradigm shift in contemporary hip hop and popular culture.[360][361] His discography became a catalyst in the upsurge of social conscience across multiple generations; challenging the status quo by encouraging listeners to reexamine social institutions.[362] Throughout the Black Lives Matter movement and events following the 2016 U.S. presidential election, his work has been used as protest anthems.[363] According to American studies and media scholar William Hoynes, Lamar's progressive elements places him amongst other African American artists and activists who "worked both inside and outside of the mainstream to advance a counterculture that opposes the racist stereotypes being propagated in white-owned media and culture."[364] He has been credited with reviving jazz rap and the music video as a form of social commentary.[365][366]

Lamar's music has consistently garnered critical acclaim and commercial success—a rare combination in the music industry—as well as support from artists who have paved the way for his advancement, earning him the nickname "King Kendrick".[367][368] His Pulitzer Prize win was considered a sign of the American cultural elite formally recognizing hip hop as a "legitimate artistic medium".[369] Senior artists such as Nas,[370] Bruce Springsteen,[371] Eminem,[372] Dr. Dre,[373] Prince,[374] and Madonna have praised his musicianship.[375] David Bowie's final album, Blackstar (2016), was inspired by To Pimp a Butterfly, and its producer Tony Visconti praised Lamar as a "rulebreaker" in the music industry.[376][377] Pharrell Williams called him "one of the greatest writers of our times" and likened him to Bob Dylan.[378] Lamar has also been cited as a strong influence on the works of various modern artists,[379] including BTS,[380] Dua Lipa,[381] Tyler, the Creator,[382] Roddy Ricch,[383] and Rosalía.[384] Lorde regards him as "the most popular and influential artist in modern music."[385]

Public image

Despite becoming a prominent figure in popular culture, publications have noted Lamar's unconventional approach to celebrity culture.[386] He is notoriously reserved, reluctant to publicly discuss his personal life and generally avoids using social media.[387][388] He is also decisive when engaging with mainstream media outlets, although journalists have complimented his "Zen-like" calmness and down to earth personality.[389][390] According to Lamar, he has become "so invested in who I am outside of being famous, sometimes that's all I know. I've always been a person that really didn't dive too headfirst into wanting and needing attention. I mean, we all love attention, but for me, I don't necessarily adore it."[391] His lyrics have been a topic of media scrutiny, leading to both praise and controversy.[15][392][393]

Lamar's public perception has also been influenced by the various rap feuds he has been involved with.[394][395] Although journalists unanimously declared him the winner of his highly publicized conflict with Drake,[396] some felt that his victory was pyrrhic due to the severity of accusations introduced and the spread of online misinformation.[397][398] Following the release of Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, media outlets have described Lamar as the "modern hip hop messiah".[399] Some critics dislike his "grating" political infusions,[400] causing him to be viewed as having a savior complex.[401][402] However, Lamar has declared himself to be the "greatest rapper alive" due to his personal connection to hip hop.[403] "I'm not doing it to have a good song, or one good rap, or a good hook, or a good bridge," he explained to Zane Lowe. "I want to keep doing it every time, period. And to do it every time, you have to challenge yourself and you have to confirm to yourself—not anybody else, confirm to yourself that you're the best, period. [...] That's my drive and that's my hunger, I will always have."[404]

Other ventures

Entrepreneurship

Lamar has been described as an "authentic" businessman who takes "calculated steps to establish his brand from the ground-up" and leaves nothing to chance.[405] He approaches traditional album rollouts with an unorthodox method, using creative Easter eggs and leaving cryptic messages.[406] Before releasing a studio album, Lamar shares a promotional single taken from "The Heart", a timestamp song series designed to "observe the beating pulse behind his music."[407] The vulnerable themes explored on the non-album singles have strengthened his relationship with his "inquisitive" fanbase known as Kenfolk.[407][408] His real estate portfolio includes properties in California and New York.[409][410] In 2011, Lamar crafted an original song with record producer Nosaj Thing to promote Microsoft's Windows Phone in 2011.[411] He starred alongside DJ Calvin Harris and singer Ellie Goulding in a marketing campaign for Bacardi in 2014.[412]

As a minority shareholder of TDE, Lamar was set to serve as the executive producer for the label's film division.[29] He partnered with American Express on advertising campaigns for Art Basel and Small Business Saturday,[413] and is an angel investor of the music creation platform EngineEars.[414] Lamar has also partnered with several fashion designers and outlets. As a brand ambassador, he was involved with designing sneakers for Reebok and Nike.[415][416] He developed working relationships with Grace Wales Bonner and Martine Rose; through their respective eponymous brands, they have dressed him for several public events.[417] For her Autumn/Winter 2023 collection, Twilight Reverie, Lamar worked with Bonner to create the show's soundtrack with Sampha and Duval Timothy.[418][419] Through PGLang, he composed the score and co-designed the stage for Chanel's Spring/Summer 2024 haute couture collection.[420]

Philanthropy and activism

A supporter of the Black Lives Matter movement, Lamar is a vocal advocate for racial equality.[421] In 2012, he commended Frank Ocean for coming out and endorsed Barack Obama's presidential re-election campaign, claiming his opponent Mitt Romney does not have a "good heart".[422][423] Lamar developed a strong friendship with Obama,[424] having worked on a promotional video for Obama's My Brother's Keeper initiative and performed at his Independence Day celebration at the White House.[425][426] He was critical of Donald Trump's first presidency and the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.[427][428]

Lamar has headlined charity concerts benefitting local and international non-profit organizations.[429][430] He donated to the American Red Cross in November 2012 to support victims of Hurricane Sandy.[431] In December 2013, Lamar donated $50,000 to his alma mater, Centennial High School, in support of its music department.[432] He embarked on a small concert tour in 2014, and donated all of the revenue to Habitat for Humanity and his hometown.[433] In July 2017, Lamar purchased a wheelchair-accessible van for a quadriplegic fan.[434][435] He has regularly performed at TDE's annual holiday toy drive at Nickerson Gardens,[436][437] and organizes his own toy drive in Compton.[438] He joined a peace walk in June 2020 to protest against the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.[439][440] In June 2024, Lamar spearheaded a $200,000 donation to 20 charities and community initiatives based in Los Angeles.[441]

Achievements

Throughout his career, Lamar has won 17 Grammy Awards (the third-most by a rapper in history),[442][443] a Primetime Emmy Award,[444] four American Music Awards,[445] 37 BET Hip Hop Awards (the most won by any artist),[446] 11 MTV Video Music Awards (including two Video of the Year wins),[447] 6 Billboard Music Awards,[448] and a Brit Award.[449] As a songwriter, he has received nominations for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe Award.[450][451] At the 58th Annual Grammy Awards, Lamar received the most Grammy nominations by a rapper in one night, with 11.[452][144] During the 65th ceremony, he became the first artist from any genre to be nominated for Album of the Year with four consecutive lead studio albums since Billy Joel (1979–1983).[453]

Lamar has appeared in various power listings. In 2015, he was featured on Ebony's Power 100 list that honors leaders within the African American community.[454] Time included him on its annual list of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2016.[455] He has appeared on Forbes' Celebrity 100 ranking (2019),[456] and its 30 Under 30 list twice in the music category (2014 and 2018).[457][458] Lamar was included twice in Billboard's lists of the greatest rappers of all time (2015 and 2023).[459][460] Complex named him the best rapper alive twice (2013 and 2017),[461][462] and included him in their list of the 20 best rappers in their 20s thrice (2013, 2015, and 2016).[463] In May 2015, Lamar was declared a generational icon by the California State Senate for his contributions to music and philanthropy.[464] He was a grand marshal for the Compton Christmas Parade,[465] and was presented with the key to the city of his hometown for representing its evolution.[362] He served as Compton College's surprise commencement speaker on June 7, 2024.[466] Lamar is the fifth man to appear solo on the cover of Harper's Bazaar.[467]

Good Kid, M.A.A.D City, To Pimp a Butterfly, and Damn were featured in Rolling Stone's industry-voted ranking of the 500 greatest albums of all time and the 200 greatest hip hop albums of all time.[468][469] Good Kid, M.A.A.D City was additionally featured in the magazine's list of the 100 best debut albums of all time, and was named the greatest concept album ever.[470][471] It was named the seventh greatest album of all time by Apple Music in 2024.[472] To Pimp a Butterfly was ranked by several publications as one of the greatest albums of the 2010s decade,[473] while "Alright" was deemed the greatest hip hop song of the streaming era by Spotify.[474] As of February 2023, it is the top ranked album on the online encyclopedia Rate Your Music.[475] Damn is the recipient of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, the first time a musical work outside of the classical and jazz genres was honored.[476][477] Its tour companion, along with Big Steppers Tour (2022–2024), are two of the highest-grossing hip hop tours of all time.[478]

Discography

Studio albums

- Section.80 (2011)

- Good Kid, M.A.A.D City (2012)

- To Pimp a Butterfly (2015)

- Damn (2017)

- Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers (2022)

- GNX (2024)

Filmography

- Lennon or McCartney (2014)

- Quincy (2018)

- Kendrick Lamar Live: The Big Steppers Tour (2022)

- Renaissance: A Film by Beyoncé (2023)

- Piece by Piece (2024)

Tours

Headlining

- Good Kid, M.A.A.D City World Tour (2013)

- Kunta's Groove Sessions (2015)

- The Damn Tour (2017–2018)

- The Big Steppers Tour (2022–2024)

Co-headlining

- The Championship Tour (with Top Dawg Entertainment artists) (2018)

- Grand National Tour (with SZA) (2025)

See also

- List of American Grammy Award winners and nominees

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of artists who reached number one on the U.S. Rhythmic chart

- List of black Golden Globe Award winners and nominees

- Music of California

Notes

- ^ For his work with Black Hippy, see Black Hippy discography.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Jackson, Mitchell S. (December 27, 2022). "Kendrick Lamar's New Chapter: Raw, Intimate and Unconstrained". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 7, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eells, Josh (June 22, 2015). "The Trials of Kendrick Lamar". Rolling Stone. pp. 40–45. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Edwards, Gavin (January 9, 2015). "Billboard Cover: Kendrick Lamar on Ferguson, Leaving Iggy Azalea Alone and Why 'We're in the Last Days'". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Miranda J (September 18, 2013). "Did You Know Kendrick Lamar Was Named After One Of The Temptations?". XXL. Archived from the original on April 23, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Hopper, Jessica (October 9, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar: Not Your Average Everyday Rap Savior". Spin. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Muhammad, Latifah (June 3, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar Buys His Sister A New Car For Graduation". Vibe. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Aaron (August 24, 2021). "Baby Keem Announces 'Family Ties' Featuring His Cousin Kendrick Lamar". UPROXX. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Palladino, Paul (October 31, 2012). "Interview: Nick Young Talks Style, His Cousin Kendrick Lamar and His Experience With a Fire Extinguisher". Complex. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Pearce, Sheldon (October 26, 2020). "Kendrick Lamar and the Mantle of Black Genius". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 17, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Thomas 2019, p. 51–66.

- ^ a b Greenburg, Zack O'Malley (November 14, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar, Conscious Capitalist: The 30 Under 30 Cover Interview". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 22, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Ugwu, Reggie (February 3, 2015). "The Radical Christianity Of Kendrick Lamar". BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Zisook, Brian (April 28, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar Responds to DJBooth Article About 'DAMN' Album". DJBooth. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Harris, Christopher (May 1, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar Recalls When He First Wanted To Rap". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Greene, David (December 29, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar: 'I Can't Change The World Until I Change Myself First'". NPR Music. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Hiatt, Brian (August 9, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar: The Best Rapper Alive on Bono, Mandela, Stardom and More". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ Haithcoat, Rebecca (January 20, 2011). "Born and raised in Compton, Kendrick Lamar Hides a Poet's Soul Behind "Pussy & Patron"". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2019.

- ^ Ahmed, Insanul (July 25, 2014). "Cover Story Uncut: Kendrick Lamar On Being Afraid of Going Broke, Working With Dr. Dre, & His Next Album". Complex. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore, Marcus J. (October 8, 2020). "Kendrick Lamar's Poetic Awakening". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ Cruz, Ricky (August 22, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar and the Constant Battle of Depression". Affinity Magazine. Archived from the original on September 23, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Harling, Danielle (August 9, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Revisits His High School, Speaks On Flunking Gym & Rival Gang Wars". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Coscarelli, Joe (March 16, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar on His New Album and the Weight of Clarity". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar: "All I Am Is a Vessel, Doing His Work."". Relevant Magazine. March 16, 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ^ Zela, Joel "Shake" (December 31, 2010). "Kendrick Lamar Talks J. Cole, XXL Freshman 2011, KiD CuDi, etc (Video)". 2DopeBoyz. Complex Music. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Watson, Elijah (February 18, 2016). "Principal of Kendrick Lamar's Compton High School Speaks on Kendrick's Influence". Pigeons and Planes. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ Wright, Colleen (June 9, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar, Rapper Who Inspired a Teacher, Visits a High School That Embraces His Work". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Reeves, Mosi (July 14, 2017). "Mixtape Primer: Reviewing Kendrick Lamar's Pre-Fame Output". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Greenburg, Zack O'Malley (January 4, 2016). "Meet Dave Free, Kendrick Lamar's 30 Under 30 Manager". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Datwon (September 14, 2017). "Kendrick Lamar and Anthony 'Top Dawg' Tiffith on How They Built Hip-Hop's Greatest Indie Label". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved June 25, 2023.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Talks J. Cole, XXL Freshman 2011, KiD CuDi, etc (Video)". 2Dopeboyz. Complex Music. December 31, 2010. Archived from the original on January 23, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ^ Weiss, Jeff (August 17, 2010). "Jay Rock, Kendrick Lamar, Ab-Soul and Schoolboy Q form quasi-supergroup Black Hippy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ Coleman II, C. Vernon (January 31, 2021). "The Game Claims He's the Best Rapper From Compton, Says He Showed Kendrick Lamar the Ropes". XXL. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ Josephs, Brian; McKinney, Jessica (December 8, 2020). "22 Things You Didn't Know About Kendrick Lamar". Complex. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Harling, Danielle (May 12, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Speaks on Previously Being Signed to Def Jam". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar - C4, Hosted by DJ Ill Will, DJ Dave". DatPiff. January 30, 2009. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ Saponara, Michael (February 28, 2018). "Nipsey Hussle Remembers When The Game Carried the West Coast on Hig Back". XXL. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar Remembers Touring With Nipsey Hussle In 2009". Vibe. April 11, 2019. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ Berry, Peter A. (June 17, 2020). "Here Are 50 Surprising Facts about Kendrick Lamar". XXL. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Ryon, Sean (June 10, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Talks Name Change, Growing Up in Compton". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar – Kendrick Lamar (FreEP)". 2DopeBoyz. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on March 19, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ a b "Kendrick Lamar Eyeing New Publishing Deal: Sources". Billboard. January 16, 2018. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Thompson, Paul (April 13, 2017). "What Does Kendrick Lamar's Overly Dedicated Tell Us About DAMN.?". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, Rauly (November 1, 2012). "Chart Juice: Kendrick Lamar's 'good kid, m.A.A.d city' Rules R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c Horowitz, Steven J. (August 2, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Says "good kid, m.A.A.d City" Will Sound "Nothing" Like "Section.80"". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Jacobs, Allen (December 17, 2010). "Dr. Dre Says In 2011, He's Focusing On West Coast Hip Hop - Kendrick Lamar, Slim da Mobster". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Reeves, Mosi (July 31, 2015). "'Detox': A Timeline of Dr. Dre's Great Unfinished Album". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Paine, Jake (December 25, 2010). "Kendrick Lamar Reacts To Dr. Dre's Cosign, Considering Aftermath". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ Espinoza, Joshua (December 25, 2021). "J. Cole Says He Urged Dr. Dre to Sign an Up-and-Coming Kendrick Lamar". Complex. Archived from the original on December 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2021.

- ^ Todd, Jessica (October 21, 2016). "Nitty Scott on What She Learned While Dating Kendrick Lamar". VladTV. Archived from the original on September 13, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Hernandez, Victoria (January 30, 2015). "Nitty Scott Talks Dating Kendrick Lamar & Changing Her Image". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Blanco, Alvin (February 22, 2011). "'XXL' Magazine Unveils 2011 'Freshman' Class". MTV. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar's 3rd Solo Album..." 2Dopeboyz. April 11, 2011. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar - HiiiPoWeR (prod. by J. Cole)". 2Dopeboyz. April 13, 2011. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (July 2, 2021). "Kendrick Lamar 'Section.80' Review: Looking Back 10 Years Later". Stereogum. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Fleischer, Adam (July 5, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar, Section.80". XXL. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ^ Payne, Ogden (July 2, 2016). "How Kendrick Lamar's 'Section.80' Catapulted Him into Hip-Hop Royalty". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Jacobs (July 6, 2011). "Hip Hop Album Sales: The Week Ending 7/3/2011". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Cooper, Roman (November 22, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Talks "Section 80," Wu-Tang Clan, Rumored Album With J. Cole". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ Ahmed, Insanul; Michels, Eric (August 1, 2011). "Interview: Kendrick Lamar Talks 'Section.80,' Major Labels, & Working With Dr. Dre". Complex. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ Gale, Alex (May 23, 2013). "20 Legendary Hip-Hop Concert Moments". Complex. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Dream Urban Presents : Kendrick Lamar Experience (Snoop Dogg Passes Torch)". YouTube. August 22, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ Markman, Rob (December 7, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Kicks Off Hottest Breakthrough MCs!". MTV. Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Harling, Danielle (May 16, 2011). "Kendrick Lamar Hoping To Release Studio Album Next Year". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on June 20, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Markman, Rob (October 24, 2011). "Drake 'Fought' For Intimate Campus Dates Over Stadium Tour". MTV News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Rebello, Ian (November 13, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole Collaboration Album Will Have No Release Date, Will "Drop Out The Sky"". The Versed. Freshcom Media LLC. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Darville, Jordan (November 3, 2023). "J. Cole on collab album with Kendrick Lamar: "We put it to bed years ago"". The Fader. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved November 23, 2023.

- ^ Alexis, Nadeska (March 8, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar, Black Hippy Ink Deals With Interscope And Aftermath". MTV. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ "Kendrick Lamar ft. Dr. Dre - "The Recipe"". Complex. April 2, 2012. Archived from the original on October 17, 2022. Retrieved October 17, 2022.

- ^ Gilman, Hannah (June 27, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar, A$AP Rocky Announce Album Release Dates". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Capobianco, Ken (October 22, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar, 'good kid, m.A.A.d city'". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Horowitz, Steven J. (August 2, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Says "good kid, m.A.A.d City" Will Sound "Nothing" Like "Section.80"". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Zisook, Brian "Z" (May 15, 2018). "Kendrick Lamar's "Swimming Pools (Drank)" Beat Was Originally a Demo for Trey Songz". DJBooth. Archived from the original on September 27, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Galindo, Thomas (June 29, 2023). "The Story Behind Kendrick Lamar's "Swimming Pools (Drank)"". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Battan, Carrie (February 22, 2013). "Watch: Kendrick Lamar and Drake Star in a Story of Love and Murder in the Video for "Poetic Justice"". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Isenberg, Daniel (March 13, 2013). "Jay-Z Is On Kendrick Lamar's "B***h Don't Kill My Vibe" Remix". Complex. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ Kot, Greg (October 21, 2012). "Album review: Kendrick Lamar, 'good kid, m.A.A.d city'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (October 31, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar Debuts at No. 2 as Taylor Swift's 'Red' Tops Billboard 200". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Ugwu, Reggie (October 31, 2012). "Kendrick Lamar's good kid, m.A.A.d. city Debuts at No. 2". BET. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Rolli, Bryan (October 25, 2019). "With 'Good Kid, M.A.A.D City,' Kendrick Lamar Tops Eminem For Billboard 200's Longest-Charting Hip-Hop Studio Album". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 24, 2023. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ Mahadevan, Tara C. (October 21, 2022). "Kendrick Lamar's 'Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City' Spends 10 Successive Years on Billboard 200 Chart". Complex. Archived from the original on October 25, 2022. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

- ^ Isenberg, Daniel (September 16, 2012). "Photo Recap: Kendrick Lamar, ScHoolboy Q, Ab-Soul, and Stalley Rock BET's Music Matters Tour in D.C." Complex. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Alexis, Nadeska (October 10, 2012). "BET Hip Hop Awards Performance Recap: T.I., Diddy, Rick Ross, French Montana, More". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (October 18, 2012). "A$AP Rocky Teams With Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar on 'F--kin' Problem'". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

- ^ Kent, Chloe (April 18, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar, Steve Aoki bring 'verge culture' to campus". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Josephs, Brian (April 20, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Announces "good kid, m.A.A.d city" World Tour". Complex. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Geslani, Michael (April 3, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar struggled with depression and suicidal thoughts while recording To Pimp A Butterfly". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Battan, Carrie (September 6, 2013). "Kanye West Announces Tour With Kendrick Lamar". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Gordon, Jeremy (June 25, 2014). "TDE Didn't Want Kendrick Lamar to Do Kanye West's Yeezus Tour, Kendrick and Kanye Barely Spoke". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 29, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ Pannell, Ni'Kesia (November 18, 2013). "Rapper Kendrick Lamar Announces Baptism On Stage At LA Concert". Julibee. Archived from the original on August 22, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (June 21, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar: 'I am Trayvon Martin. I'm all of these kids'". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Markman, Rob (October 15, 2013). "2013 BET Hip Hop Awards: The Complete Winners List". MTV. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- ^ Graham, Nadine (September 29, 2013). "2 Chainz, Kendrick Lamar Shine At 2013 BET Hip-Hop Awards". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Harling, Danielle (June 30, 2013). "Chris Brown, Nicki Minaj, 2 Chainz & More Perform At The BET Awards". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Katie (June 30, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Brings Out Erykah Badu At The 2013 BET Awards". Complex. Archived from the original on June 19, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ Markman, Rob (January 22, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar To 'SNL': 'Put Me in One of Those Skits!'". MTV News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ Ramirez, Erika (April 10, 2013). "Miguel Releases Kendrick Lamar-Assisted 'How Many Drinks?' Remix: Listen". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 26, 2023. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Diep, Eric (June 11, 2013). "ScHoolboy Q ft. Kendrick Lamar "Collard Greens"". XXL. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Ex, Kris (August 22, 2013). "The Blast Radius Of Kendrick Lamar's 'Control' Verse". NPR. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015.

- ^ Phili, Stelios (May 7, 2013). "Robin Thicke on That Banned Video, Collaborating with 2 Chainz and Kendrick Lamar, and His New Film". GQ. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Nessif, Bruna (October 10, 2013). "Eminem Releases Marshall Mathers LP 2 Track List, Reveals Collaborations With Rihanna, Kendrick Lamar & More". E!. NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ Lamarre, Carl (May 6, 2024). "Drake & Kendrick Lamar's Rocky Relationship Explained". Billboard. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ Shipley, Al; Reeves, Mosi; Lee, Christina (March 11, 2015). "9 Ways Kendrick Lamar's 'Control' Verse Changed the World". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2023.

- ^ X, Dharmic (November 11, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar Named GQ's Rapper of the Year, Talks About Drake: "[We're] Pretty Cool, and I Would Be Okay if We Weren't"". Complex. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Ortiz, Edwin (November 15, 2013). "TDE CEO Attacks GQ Story on Kendrick Lamar as Having 'Racial Overtones,' Pulls Lamar From GQ Party". Complex. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Markman, Rob (November 15, 2013). "Kendrick Lamar's Camp Takes Aim at GQ's 'Racial' Man of the Year Cover Story". MTV. Archived from the original on February 6, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 2014: Full Nominations List". Billboard. December 6, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Sperry, April (January 26, 2014). "Here Are The Biggest Snubs of the 2014 Grammys". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Greatest Grammy Snubs of All Time". Vulture. January 20, 2020. Archived from the original on January 21, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (January 27, 2014). "Read Macklemore's Apology Text To Kendrick Lamar For Winning Best Rap Album Grammy". Sterogum. Archived from the original on January 30, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ Locker, Melissa (January 27, 2014). "Grammys 2014: Macklemore Says Kendrick Lamar "Was Robbed" On Best Rap Album". Time. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Llacoma, Janice (January 26, 2014). "Kendrick Lamar & Imagine Dragons "m.A.A.d city" & "Radioactive" (2014 GRAMMY Performance)". HipHopDX. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Catucci, Nick (January 27, 2014). "How Kendrick Lamar (and Imagine Dragons) won the Grammys". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (October 21, 2013). "Eminem, Kendrick Lamar & J. Cole Heading Down Under for 'Rapture' Stadium Tour". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Lacy, Eric (February 19, 2014). "Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, Action Bronson, J. Cole hit Australia for Rapture Tour; view fan photos". Michigan Live. Archived from the original on April 21, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Forman, Olivia (July 31, 2014). "Kendrick Lamar's 'M.A.A.D' Short Film Headed To Sundance NEXT Fest". Spin. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Frydenlund, Zach (September 23, 2014). "Listen to Kendrick Lamar's "I"". Complex. Archived from the original on July 22, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ "Grammys 2015: Kendrick Lamar and Eminem Win Big in Rap Categories". The Hollywood Reporter. February 8, 2015. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Coleman, Miriam (November 16, 2014). "Kendrick Lamar Makes a Triumphant Return to 'SNL'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Ashley (March 31, 2014). "Alicia Keys, Kendrick Lamar Release 'Amazing Spider-Man 2' Song (Audio)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Geslani, Michelle (April 7, 2014). "Listen: SZA's new version of "Babylon", featuring Kendrick Lamar". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- ^ Grow, Kory (September 3, 2014). "Hear Flying Lotus and Kendrick Lamar's Jazzy Song 'Never Catch Me'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ Stutz, Colin (October 15, 2014). "Drake, DJ Mustard Take Top Honors at 2014 BET Hip Hop Awards: Full Winners List". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Ryan, Patrick (March 16, 2015). "Kendrick Lamar's new album arrives early". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Kornhaber, Stephen (March 17, 2015). "The Power in Kendrick Lamar's Complexity". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2016.