Genetic studies on Sinhalese

Genetic studies on the Sinhalese is part of population genetics investigating the origins of the Sinhalese population.

All studies agree that there is a significant relationship between the Sinhalese and the Bengalis and South Indian Tamils, and that there is a significant genetic relationship between Sri Lankan Tamils and Sinhalese. This is also supported by a genetic distance study, which showed low differences in genetic distance between the Sinhalese and the Bengali, Tamil, and Keralite volunteers.

Relationship to Bengalis

[edit]

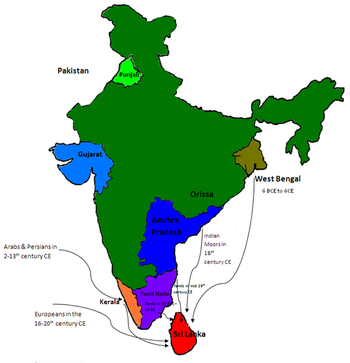

An Alu polymorphism analysis by Mastana S (2007) using Sinhalese, Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati (Patel), and Punjabi as parental populations found the following proportions of genetic contribution. The Sinhalese sample size used was 121 individuals.:[2]

| Statistical Method | Bengali | Tamil | North Western |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Estimate | 57.49% | 42.5% | - |

| Maximum Likelihood Method | 88.07% | - | - |

| Using Tamil, Bengali and North West as parental population | 50-66% | 11-30% | 20-23% |

| Parental population | Bengali | Tamil | Gujarati | Punjabi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using Tamil and Bengali as parental population | 70.03% | 29.97% | - | |

| Using Tamil, Bengali and Gujarati as parental population | 71.82% | 16.38% | 11.82% | |

| Using Bengali, Gujarati and Punjabi as parental population | 82.09% | - | 15.39% | 2.52% |

Analysis of X chromosome STRs by Perera et al. (2021) found the Sinhalese (as well as Sri Lankan Tamils and Sri Lankan Muslims) to be more closely related to Bengalis, than to the Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka.[3]

Genetic distance analysis by Kirk (1976) found the Sinhalese to be closer to the Bengal than they are to populations in Gujarat or the Panjab.[4]

D1S80 allele frequency (a popular allele for genetic fingerprinting) is also similar between the Sinhalese and Bengalis, suggesting the two groups are closely related.[5]

The Sinhalese also have similar frequencies of the allele MTHFR 677T (13%) to West Bengalis (17%).[6][7]

Relationship to Indian Tamils

[edit]

A genetic admixture study by Kshatriya (1995) found the Sinhalese to have a higher contribution from Indian Tamils (69.86% +/- 0.61), compared with the Bengalis (25.41% +/- 0.51).[8]

Genetic distance analysis by Roychoudhury AK et al. (1985) suggested the Sinhalese are more closely related to South and West Indian populations, than the Bengalis.[9]

Genetic distance analysis by Kirk (1976) suggested the Sinhalese are closer to the Tamils and Keralites of South India, than they are to the populations in Gujarat or the Panjab.[4]

A 2023 study by Singh et al using higher resolution markers than previous studies found that there was higher gene flow from South India to the Sinhalese than from North India, with the Sinhalese sharing the highest Identity by descent with Tamils specially Piramalai Kallars, compared to the other Indian populations studied. The study also found heightened sharing with the Maratha of India , consistent with a West Eurasian contribution .This excess sharing of segments suggests common roots of Sinhala with the Marāṭhā corroborating the linguistic hypothesis of Lazarus Geiger, Ralph Lilley Turner, and George van Driem. The total Sinhalese sample size used was 9 individuals. [10]

Relationship to North West Indians

[edit]An Alu polymorphism analysis by Mastana S (2007) found a North West Indian contribution (20-23%).[11]

Analysis of X chromosome STRs by Perera et al., (2011) showed that the Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamil, Moor and Indian Tamils of Sri Lanka, share affinities with the Bhil (an Indigenous group) of North West India.[12]

Relationship to other major ethnic groups in Sri Lanka

[edit]A study looking at genetic variation of the FUT2 gene in the Sinhalese and Sri Lankan Tamil population, found similar genetic backgrounds for both ethnic groups, with little genetic flow from other neighbouring Asian population groups.[13] Studies have also found no significant difference with regards to blood group, blood genetic markers (Saha, 1988) and single-nucleotide polymorphism between the Sinhalese and other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka.[14][15][16] Another study has also found "no significant genetic variation among the major ethnic groups in Sri Lanka".[17] This is further supported by a study which found very similar frequencies of alleles MTHFR 677T, F2 20210A & F5 1691A in Indian Tamil, Sinhalese, Sri Lankan Tamil, and Sri Lankan Moor populations.[7]

Relationship to other South Asians and West Asians

[edit]A 1985 study conducted by Roychoudhury AK and Nei M indicating the values of genetic distance showed that the Sinhalese, along with the four Indian subcontinent populations from Punjab, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Bangladesh, were closer to Afghans and Iranians than the neighboring East/Southeast Asian groups represented by the Bhutanese, Malays, Bataks in northern Sumatra, and the Chinese.[9]

Relationship to East and Southeast Asians

[edit]Genetic markers of immunoglobulin among the Sinhalese show high frequencies of afb1b3 which has its origins in the Yunnan and Guangxi provinces of southern China.[18] It is also found at high frequencies among Odias, certain Nepali and Northeast Indian, southern Han Chinese, Southeast Asian and certain Austronesian populations of the Pacific Islands.[18] At a lower frequency, ab3st is also found among the Sinhalese and is generally found at higher frequencies among northern Han Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian, Korean and Japanese populations.[18] The Transferrin TF*Dchi allele which is common among East Asian and Native American populations is also found among the Sinhalese.[9] HumDN1*4 and HumDN1*5 are the predominant DNase I genes among the Sinhalese and are also the predominant genes among southern Chinese ethnic groups and the Tamang people of Nepal.[19] A 1988 study conducted by N. Saha, showed the high GC*1F and low GC*1S frequencies among the Sinhalese are comparable to those of the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Thais, Malays, Vietnamese, Laotians and Tibetans.[20] Hemoglobin E a variant of normal hemoglobin, which originated in and is prevalent among populations in Southeast Asia, is also common among the Sinhalese and can reach up to 40% in Sri Lanka.[21]

Maternal Line

[edit]MtDNA of Sinhalese

[edit]Ranweera et al. (2014) found the most common mtDNA haplogroup in the Sinhalese to be, Haplogroup M and Haplogroup U (U7a) , Haplogroup R and Haplogroup G (G3a1′2).[22][23]

Haplogroup M represents the dispersal of modern humans around 60.000 years ago along the southern Asian coastline following a southern coastal route across Arabia and India to reach Australia short after.[24]

Haplogroup U7 is considered a West Eurasian–specific mtDNA haplogroup, believed to have originated in the Black Sea area approximately 30,000 years ago. In South Asia, U7 occurs in about 12% in Gujarat, while for the whole of India its frequency stays around 2%, and 5% in Pakistan. In the Vedda people of Sri Lanka it reaches its highest frequency of 13.33% (subclade U7a). It is speculated that large-scale immigration carried these mitochondrial haplogroups into India.[25]

Paternal Line

[edit]Y-DNA of Sinhalese

[edit]Kivisild et al.(2003) found the most common Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups found in the Sinhalese are Haplogroup R2, Haplogroup L, Haplogroup R1a and F in that order.[26]

| Population | n | C | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | N | O | P | Q | R | R1 | R1a | R1b | R2 | T | Others | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinhalese | 39 | 0 | 0 | 10.3% | 0 | 10.3% | 0 | 10.3% | 0 | 18% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.8% | 0 | 38.5% | 0 | Kivisild2003[26] |

Chaubey states that "considerable number of maternal lineages of Sri Lanka is shared with India, more precisely with southern part of India."[27]

References

[edit]- ^ Kirk, R. L. (July 1976). "The legend of Prince Vijaya — a study of Sinhalese origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450112.

- ^ Mastana S (2007). "Molecular anthropology: population and forensic genetic applications" (PDF). Anthropologist Special. 3: 373–383.

- ^ Perera, N., Galhena, G. and Ranawaka, G., 2021. X-chromosomal STR based genetic polymorphisms and demographic history of Sri Lankan ethnicities and their relationship with global populations. Scientific reports, 11(1), pp.1-12.

- ^ a b Kirk RL (July 1976). "The legend of Prince Vijaya – a study of Sinhalese origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450112.

- ^ Surinder Singh Papiha (1999). Genomic Diversity: Applications in Human Population Genetics. London: Springer. 7.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay K, Dutta S, Das Bhomik A (January 2007). "MTHFR gene polymorphisms analyzed in population from Kolkata, West Bengal". Indian Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (1): 38. doi:10.4103/0971-6866.32035. PMC 3168154. PMID 21957342.

- ^ a b Dissanayake VH, Weerasekera LY, Gammulla CG, Jayasekara RW (October 2009). "Prevalence of genetic thrombophilic polymorphisms in the Sri Lankan population--implications for association study design and clinical genetic testing services". Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 87 (2): 159–62. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2009.07.002. PMID 19591822.

- ^ Kshatriya GK (December 1995). "Genetic affinities of Sri Lankan populations". Human Biology. 67 (6). American Association of Anthropological Genetics: 843–66. PMID 8543296.

- ^ a b c Roychoudhury, Arun K.; Nei, Masatoshi (2 September 2008). "Genetic Relationships between Indians and Their Neighboring Populations". Human Heredity. 35 (4): 201–206. doi:10.1159/000153545. ISSN 0001-5652. PMID 4029959.

- ^ Prajjval Pratap Singh, Sachin Kumar, Nagarjuna Pasupuleti, Niraj Rai, Gyaneshwer Chaubey, R. Ranasinghe, "Reconstructing the population history of Sinhalese, the major ethnic group in Śrī Laṅkā," iScience, August 31, 2023, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107797.

- ^ Mastana S (2007). "Molecular anthropology: population and forensic genetic applications" (PDF). Anthropologist Special. 3: 373–383.

- ^ Perera, N., Galhena, G. and Ranawaka, G., 2021. X-chromosomal STR based genetic polymorphisms and demographic history of Sri Lankan ethnicities and their relationship with global populations. Scientific reports, 11(1), pp.1-12.

- ^ Soejima M, Koda Y (December 2005). "Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography-based genotyping and genetic variation of FUT2 in Sri Lanka". Transfusion. 45 (12): 1934–9. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00651.x. PMID 16371047. S2CID 10401001.

- ^ Saha N (1988). "Blood genetic markers in Sri Lankan populations--reappraisal of the legend of Prince Vijaya". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 76 (2): 217–25. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330760210. PMID 3166342.

- ^ Roberts DF, Creen CK, Abeyaratne KP (1972). "Blood Groups of the Sinhalese". Man. 7 (1): 122–127. doi:10.2307/2799860. JSTOR 2799860.

- ^ Dissanayake VH, Giles V, Jayasekara RW, Seneviratne HR, Kalsheker N, Broughton Pipkin F, Morgan L (April 2009). "A study of three candidate genes for pre-eclampsia in a Sinhalese population from Sri Lanka". The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 35 (2): 234–42. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00926.x. PMID 19708171. S2CID 24958292.

- ^ Illeperuma RJ, Mohotti SN, De Silva TM, Fernandopulle ND, Ratnasooriya WD (June 2009). "Genetic profile of 11 autosomal STR loci among the four major ethnic groups in Sri Lanka". Forensic Science International. Genetics. 3 (3): e105-6. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2008.10.002. PMID 19414153.

- ^ a b c Matsumoto H (2009). "The origin of the Japanese race based on genetic markers of immunoglobulin G". Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and Biological Sciences. 85 (2): 69–82. Bibcode:2009PJAB...85...69M. doi:10.2183/pjab.85.69. PMC 3524296. PMID 19212099.

- ^ Fujihara J, Yasuda T, Iida R, Ueki M, Sano R, Kominato Y, et al. (July 2015). "Global analysis of genetic variations in a 56-bp variable number of tandem repeat polymorphisms within the human deoxyribonuclease I gene". Legal Medicine. 17 (4): 283–6. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2015.01.005. PMID 25771153.

- ^ Malhotra R (1992). Anthropology of Development: Commemoration Volume in the Honour of Professor I.P. Singh. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-328-5.[page needed]

- ^ Kumar D (2012). Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-2231-9.[page needed]

- ^ Ranaweera, Lanka; Kaewsutthi, Supannee; Win Tun, Aung; Boonyarit, Hathaichanoke; Poolsuwan, Samerchai; Lertrit, Patcharee (January 2014). "Mitochondrial DNA history of Sri Lankan ethnic people: their relations within the island and with the Indian subcontinental populations". Journal of Human Genetics. 59 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.112. PMID 24196378.

- ^ Ranasinghe, Ruwandi; Tennekoon, Kamani H.; Karunanayake, Eric H.; Lembring, Maria; Allen, Marie (November 2015). "A study of genetic polymorphisms in mitochondrial DNA hypervariable regions I and II of the five major ethnic groups and Vedda population in Sri Lanka". Legal Medicine. 17 (6): 539–546. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2015.05.007. PMID 26065620.

- ^ Marrero, P.; Abu-Amero, K. K.; Larruga, J. M.; Cabrera, V. M. (2016). "Carriers of human mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup M colonized India from southeastern Asia". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16 (1): 246. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0816-8. PMC 5105315. PMID 27832758.

- ^ Metspalu M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, Parik J, Hudjashov G, Kaldma K, et al. (August 2004). "Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans". BMC Genetics. 5: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-5-26. PMC 516768. PMID 15339343.

- ^ a b Kivisild T, Rootsi S, Metspalu M, Mastana S, Kaldma K, Parik J, et al. (February 2003). "The genetic heritage of the earliest settlers persists both in Indian tribal and caste populations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (2): 313–332. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373.

- ^ Chaubey, G. Language isolates and their genetic identity: a commentary on mitochondrial DNA history of Sri Lankan ethnic people: their relations within the island and with the Indian subcontinental populations. J Hum Genet 59, 61–63 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2013.122