John Hunt Morgan

John H. Morgan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Thunderbolt |

| Born | June 1, 1825 Huntsville, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | September 4, 1864 (aged 39) Greeneville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States Confederate States of America |

| Service | US Army Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1846–1847 (USA) 1857–1861 (Kentucky militia) 1861–1864 (CSA) |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | Mexican–American War Battle of Buena Vista American Civil War Battle of Shiloh Battle of Hartsville Morgan's Raid Battle of Tebbs Bend Battle of Corydon Battle of Buffington Island Battle of Salineville Battle of Cynthiana |

| Spouse(s) | Rebecca Gratz Bruce Martha Ready |

| Signature | |

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825 – September 4, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War. In April 1862, he raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, fought at Shiloh, and then launched a costly raid in Kentucky, which encouraged Braxton Bragg's invasion of that state. He also attacked General William Rosecrans's supply lines. In July 1863, he set out on a 1,000-mile raid into Indiana and Ohio, taking hundreds of prisoners. But after most of his men had been intercepted by U.S. Army gunboats, Morgan surrendered at Salineville, Ohio, the northernmost point ever reached by uniformed Confederates. Morgan carried out the diversionary "Morgan's Raid" against orders, which gained no tactical advantage for the Confederacy while losing the regiment. Morgan escaped prison, but his credibility was so low that he was restricted to minor operations. He was killed at Greeneville, Tennessee, in September 1864. Morgan was the brother-in-law of Confederate general A. P. Hill. Various schools and a memorial are dedicated to him.

Early life and career

[edit]John H. Morgan was born in Huntsville, Alabama, the eldest of ten children of Calvin and Henrietta (Hunt) Morgan. He was an uncle of geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan and a maternal grandson of John Wesley Hunt, an early founder of Lexington, Kentucky, and one of the first millionaires west of the Allegheny Mountains.[citation needed] He was also the brother-in-law of A. P. Hill and of Basil W. Duke.[1] His first cousin, twice removed, Abijah Hunt, an important early merchant and slave trader in the Natchez District in Mississippi, was killed in a duel with Mississippi Governor George Poindexter in 1811.[2] The man we know today as John Hunt Morgan never used his middle name of Hunt during the war – it is a post-war appellation.[citation needed]

John Wesley Hunt, Morgan's grandfather, was a leading landowner and businessman in Kentucky and was the first millionaire west of the Allegheny Mountains. "His business empire included interest in banking, horse breeding, agriculture, and hemp manufacturing. Among his business associates were Henry Clay and John Jacob Astor."[citation needed]

Morgan's paternal grandparents were Luther and Anna (Cameron) Morgan. Luther Morgan had settled in Huntsville, but a downturn in the cotton economy forced him to mortgage his holdings. His father, Calvin Morgan, lost his Huntsville home in 1831 when he could not pay the property taxes following the failure of his pharmacy. The family then moved to Lexington, where he would manage one of his father-in-law's sprawling farms.

Morgan grew up on the farm outside of Lexington and attended Transylvania College for two years but was suspended in 1844 for dueling with a fraternity brother. In 1846, Morgan became a Freemason, at Daviess Lodge #22, Lexington, Kentucky.[3] Morgan desired a military career, but the small size of the U.S. military severely limited opportunities for officer's commissions.

In 1846, Morgan enlisted with his brother Calvin and uncle Alexander in the United States Army as a cavalry private during the Mexican–American War. He was elected second lieutenant and was promoted to first lieutenant before arriving in Mexico, where he saw combat in the Battle of Buena Vista. On his return to Kentucky, he became a hemp manufacturer, and in 1848, he married Rebecca Gratz Bruce, the 18-year-old sister of one of his business partners. Morgan also hired out and occasionally sold the people that he enslaved. After the death of John Wesley Hunt in 1849, his fortunes significantly improved as his mother, Henrietta, began financing his business ventures.

In 1853, Morgan's wife delivered a stillborn son. She contracted septic thrombophlebitis, popularly known as "milk leg", an infection of a blood clot in a vein, which eventually led to an amputation. They became increasingly emotionally distant from one another. Known as a gambler and philanderer, Morgan was also known for his generosity. It is rumored that he had one slave son, Sidney Morgan, by an enslaved woman and was the grandfather of African American inventor Garrett Morgan (1877–1963).[4] No historical documents exist to prove that John Hunt Morgan was the father of Sidney Morgan, or the grandfather of Garrett Morgan.[5] He was an enslaver and an investor in the Lexington slave-trading business of Lewis C. Robards.[6] Further, Sidney A. Morgan was said to have been born in 1834, when Morgan was 9 years of age.

Morgan remained interested in the military. He raised a militia artillery company in 1852, but it was disbanded by the state legislature two years later. In 1857, with the rise of sectional tensions, Morgan raised an independent infantry company known as the "Lexington Rifles" and spent much of his free time drilling the company.

American Civil War

[edit]

Like most Kentuckians, Morgan did not initially support declaring secession from the United States. Immediately after Lincoln's election in November 1860, he wrote to his brother, Thomas Hunt Morgan, then a student at Kenyon College in northern Ohio, "Our State will not I hope secede I have no doubt but Lincoln will make a good President, at least we ought to give him a fair trial & then if he commits some overt act all the South will be a unit." By the following spring, Tom Morgan (who also had opposed Kentucky's secession) transferred home to the Kentucky Military Institute and began to support the Confederacy. Just before the Fourth of July, by way of a steamer from Louisville, he quietly left for Camp Boone, just across the Tennessee border, to enlist in the Kentucky State Guard. John stayed home in Lexington to tend to his troubled business and ailing wife. Becky Morgan died on July 21, 1861.

In September, Morgan and his militia company went to Tennessee and joined the Confederate States Army. Morgan soon raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment and became its colonel on April 4, 1862.[1]

Morgan and his regiment fought at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, and he soon became a symbol to secessionists, in their hopes of occupying Kentucky for the Confederacy. A Louisiana writer, Robert D. Patrick, compared Morgan to Francis Marion and wrote that "a few thousands of such men as his would regain us Kentucky and Tennessee."[citation needed]

In his first Kentucky raid, Morgan left Knoxville on July 4, 1862, with almost 900 men and, in three weeks, swept through Kentucky, deep in the rear of Major General Don Carlos Buell's army. He reported the capture of 1,200 U.S. soldiers, whom he paroled, acquired several hundred horses, and destroyed massive quantities of supplies.[7] He unnerved Kentucky's U.S. military government and President Abraham Lincoln received so many frantic appeals for help that he complained that "they are having a stampede in Kentucky." Historian Kenneth W. Noe wrote that Morgan's feat "in many ways surpassed J. E. B. Stuart's celebrated 'Ride around McClellan' and the Army of the Potomac the previous spring." The success of Morgan's raid was one of the key reasons that the Confederate Heartland Offensive of Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith was launched later that fall, assuming that tens of thousands of Kentuckians would enlist in the Confederate Army if they invaded the state.[8]

As a colonel, the widow of Brigadier General Barnard Elliott Bee Jr. presented him with a Palmetto Armory pistol. The Museum of the American Civil War now owns that pistol.

Morgan was promoted to brigadier general (his highest rank) on December 11, 1862, though Jefferson Davis did not sign the Promotion Orders until December 14, 1862.[1] He received the thanks of the Confederate Congress on May 1, 1863, for his raids on the supply lines of U.S. Army Major General William S. Rosecrans in December and January, most notably his victory at the Battle of Hartsville on December 7.[9]

On December 14, 1862, Morgan married Martha "Mattie" Ready, the daughter of Tennessee United States Representative Charles Ready and a cousin of William T. Haskell, another former U.S. representative from Tennessee.

Morgan's Raid

[edit]

Hoping to divert U.S. troops and resources in conjunction with the twin Confederate operations of Vicksburg and Gettysburg in the summer of 1863, Morgan set off on a diversionary campaign that would become known as "Morgan's Raid". Morgan crossed the Ohio River and raided southern Indiana and Ohio. At Corydon, Indiana, the raiders met 450 local Home Guard in the Battle of Corydon, resulting in eleven Confederates and five Home Guard killed.

In July, at Versailles, Indiana, while Confederate soldiers raided nearby militia and looted county and city treasuries, the jewels of the local masonic lodge were stolen. When Morgan, a Freemason, learned of the theft, he recovered the jewels and returned them to the lodge the following day.[10]

After several more skirmishes, during which Morgan captured and paroled thousands of U.S. soldiers[citation needed], Morgan's raid almost ended on July 19, 1863, at the Battle of Buffington Island in Ohio, when approximately 700 of his men were captured while trying to cross the Ohio River into West Virginia. Intercepted by U.S. Army gunboats, over 300 of his men succeeded in crossing. Most of Morgan's men captured that day spent the rest of the war in Camp Douglas, a prisoner-of-war camp in Chicago. On July 26, near Salineville, Ohio, Morgan and his depleted soldiers finally surrendered. It was the farthest northward that any uniformed Confederate troops would penetrate during the war.[11]

On November 27, Morgan and six of his officers, most notably Thomas Hines, escaped from their cells in the Ohio Penitentiary by digging a tunnel from Hines' cell into the inner yard and then ascending a wall with a rope made from bunk coverlets and a bent poker iron. Shortly after midnight, Morgan and three of his officers boarded a train from the nearby Columbus train station and arrived in Cincinnati that morning. Morgan and Hines jumped from the train before reaching the depot and escaped into Kentucky by hiring a skiff to take them across the Ohio River. Through the assistance of insurgents, they eventually reached the Confederacy. Coincidentally, the same day Morgan escaped, his wife gave birth to a daughter, who died shortly afterward before Morgan returned.

Though Morgan's Raid was breathlessly followed by the Northern and Southern U.S. press and caused the U.S. leadership considerable concern, it was little more than a showy but ultimately futile sidelight to the war. Furthermore, Morgan had disobeyed Braxton Bragg's orders not to cross the river. Despite the raiders' best efforts, U.S. forces had amassed nearly 110,000 militia in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio; dozens of United States Navy gunboats along the Ohio; and strong U.S. cavalry forces, which doomed the raid from the beginning. The cost of the attack to the United States was extensive, with compensation claims still being filed against the U.S. government well into the early 20th century. However, the Confederacy's loss of Morgan's light cavalry outweighed the benefits.

Late career and death

[edit]After fleeing Ohio, Morgan returned to active duty. However, the men he was assigned were inexperienced compared to those he commanded previously. Morgan again began raiding into Kentucky. However, his men were undisciplined, and he was unwilling or unable to control them, leading to open pillaging along with high casualties. The raids of this season were in risky defiance of a strategic situation in the border states that had changed radically from the year before. U.S. Army defense of this region, long denied to major Confederate armies, had progressed so that even highly mobile raiders could no longer count on easily evading them. Public outrage at Morgan's raid across the Ohio River may have contributed to this state of affairs.

Morgan's "Last Kentucky Raid" was carried out in June 1864, including during the Battle of Cynthiana. After winning a minor victory on June 11 against an inferior infantry unit in the engagement known as the Battle of Keller's Bridge on the Licking River, near Cynthiana, Kentucky, Morgan chanced another engagement the following day against superior U.S. Army mounted forces that were known to be approaching. The result was a disaster for the Confederates, resulting in the destruction of Morgan's force as a cohesive unit, only a tiny fraction of whom escaped with their lives and liberty as fugitives, including Morgan and some of his officers.

Braxton Bragg never trusted Morgan again after the flashy but unauthorized 1863 Ohio raid. Nevertheless, on August 22, 1864, Morgan was placed in command of the Trans-Allegheny Department, embracing the Confederate forces in eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia at the time. Yet around this time, some Confederate authorities were quietly investigating Morgan for charges of criminal banditry,[citation needed] likely leading to his removal from command. He began to organize a raid aimed at Knoxville, Tennessee.

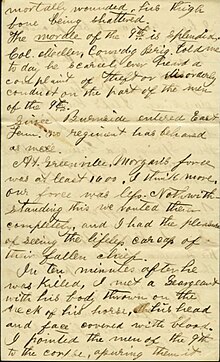

John Hunt Morgan arrived in Greeneville, Tennessee on the afternoon of Saturday, September 3, 1864. That evening a 12-year-old boy, who lived west of town, rode the 18 mi (29 km) to a U.S. cavalry encampment at Bulls Gap to report that secessionist soldiers were in his town again.[12] Confederate scouts had spotted the U.S. forces, but Morgan believed the bulk of the force were some 50 mi (80 km) at Strawberry Plains. For their part, the "Tennessee Yankees," led by Alvan C. Gillem, had inaccurate intelligence from the boy that Hunt was with maybe 300 men when, in fact, he had 1,500 soldiers and two cannons.[12] Gillem and his colonels, John K. Miller, W. H. Ingerton, and John "Belt" Brownlow,[13] determined they must seize the moment and organized what was intended to be an encirclement of the town, dividing their forces in two, with Ingerton's locally raised soldiers taking "a trail used by wood haulers,"[14] and the bulk of the force under Gillem and Brownlow taking the main road.[12] The night ride was beset by thunderstorms, which conferred two meager advantages: Confederate scouts stayed inside, and "almost constant lightning" lit their way down the muddy, mostly empty, country roads.[12]

Near morning, three civilians informed the advancing U.S. troops that they were facing a considerably larger Confederate force than they understood and that John Hunt Morgan had spent the night at the Williams mansion, where he dined with the ladies and the servants.[12] The Williams family had three sons, one a U.S. Army officer and two Confederate Army officers; thus, the family hosted officers of both armies during the war.[15] Hunt had placed pickets on three roads entering the town—but not Newport Road,[12] the one that Col. Ingerton and his men would take—and perhaps most importantly, "by placing his units a few miles outside Greeneville, Morgan rested for the night out of direct contact with his troops."[14] As Col. Ingerton approached the town, "an excited young black man" was one of the three civilians who described Morgan's whereabouts to U.S. soldiers. This was likely the first that Ingerton heard about Morgan specifically being in the area,[14] but Ingerton took the man at his word and "called upon Capt. Christopher C. Wilcox of Company G, ordering him to take his company and Northington's Company I and 'dash into town, surround the Williams' residence, and bring Morgan out dead or alive.'"[12]

The two companies under the command of Capt. Wilcox rode into town, rousted what rebel sentries were to be found, and engaged in just enough gunfire with Confederates along Main Street to awaken Morgan.[12] As U.S. soldiers entered the Williams property, they spotted "a man clad in a white shirt and trousers near the summer house. As they raced toward him, Morgan fired his pistols at them and dashed into the vineyard bordering Depot Street."[14] Morgan fled through the grape arbor toward a hotel until Pvt. Andrew Campbell caught up with his group of three.[12] Of two officers with Morgan in the shrubbery, one surrendered, and one "caught a loose horse" and escaped.[14] Despite Campbell's repeated demands that he halt, Morgan failed to comply and kept running.[12] Pvt. Campbell shot Morgan through the back, foiling his getaway.[12] The bullet traveled through his heart, and he died on the spot.[12] Only later did any of the U.S. soldiers learn who Campbell had killed when Morgan's body was identified by one of his staff officers, apparently in quite sentimental language: "You have killed the best man in the Southern Confederacy...It is General Morgan."[14]

Morgan was buried in Lexington Cemetery. The burial was shortly before the birth of his second child, another daughter.

Legacy

[edit]

Hart County High School, in Munfordville, Kentucky, the site of the Battle for the Bridge, nicknamed their athletic teams the Raiders, in memory of Morgan's men. Also, a large mural in the town depicts Morgan. Trimble County High School, in Bedford, Kentucky, also nicknamed their athletic teams the Raiders in memory of Morgan's men.

A John Hunt Morgan Memorial statue in Lexington memorializes him. The statue was relocated from the courthouse lawn in July 2018, where slave auctions were held. It was subsequently relegated to the Confederate section of the Lexington Cemetery.[17]

The Hunt-Morgan House, once his home, is a contributing property in a historic district in Lexington.

The John Hunt Morgan Bridge on East Main Street/U.S. Route 11 in Abingdon, Virginia, is named after him.

The John Hunt Morgan Bridge on South Main Street/U.S. Route 27 in Cynthiana, Kentucky, is named after him.

The General Morgan Inn, located at the spot he was killed in Greeneville, Tennessee, is named after him.

A Kentucky Army National Guard Field Artillery battalion, the 1st BN 623d FA (HIMARS) with headquarters in Glasgow, Kentucky, are known as Morgan's Men.

A statue was erected in Pomeroy, Ohio, for his effect on the town and its people.[18]

See also

[edit]- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of Notable Freemasons

- Alvan Cullem Gillem

- Battle of Buffington Island

- Battle of Corydon

- Battle of Salineville

- Guerrilla warfare

- Kentucky in the American Civil War

- Garrett Augustus Morgan

- Thomas Hunt Morgan – nephew of John Hunt Morgan, who won the 1933 Nobel Prize in Medicine

- William P. Sanders

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Eicher, p. 397.

- ^ Blaakman, Michael A.; Conroy-Krutz, Emily; Arista, Noelani (2023). The Early Imperial Republic: From the American Revolution to the U.S.–Mexican War. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 58–62. ISBN 978-0-8122-9775-1.

- ^ Smith, Dwight L. Goodly Heritage (Grand Lodge of Indiana, 1968) pg.124

- ^ Evans, Harold. Who Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine. Little Brown, 2004.

- ^ "MORGAN, GARRETT A. | Encyclopedia of Cleveland History | Case Western Reserve University". case.edu. 2023-01-27. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ "Morgan and his raiders : a biography of the Confederate General / by Cecil Fletcher Holland". HathiTrust. pp. 25–26. hdl:2027/inu.32000009053119. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

- ^ North & South - The Official Magazine of the Civil War Society, Volume 11, Number 1, Page 70, "We will have to whip these fellows sure enough" - John Hunt Morgan, accessed April 16, 2010. Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Noe, p. 31.

- ^ Eicher, p. 397. "...for their varied heroic and invaluable services in Tennessee and Kentucky immediately preceding the battles before Murfreesboro, services which have conferred upon their authors fame as enduring as the records of the struggle which they have so brilliantly illustrated."

- ^ Morgan, John. "Masonic Facts and Trivia". Education. clearwater127.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Dupuy, p. 525.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Baggett, James Alex (2009). "20. Bulls Gap". Homegrown Yankees: Tennessee's Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 325–328. ISBN 9780807136157. LCCN 2008041579. OCLC 779826648 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ "John Hunt Morgan". Chattanooga Republican. 1892-12-24. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Conklin, Forrest (1976). "Footnotes on the Death of John Hunt Morgan". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 35 (4): 376–388. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42623607.

- ^ "A House Divided". Dickson Williams Mansion (dicksonwilliamsmansion.org). Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ "Letter, John B. Brownlow in Bulls Gap, Tenn. to O. P. Temple in Knoxville, Tenn., 1864 September 07 | Digital Collections". digital.lib.utk.edu. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Bertram, Charles. "Confederate statues quietly moved to Lexington Cemetery". kentucky. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ The website 'Carnegie Library, East Liverpool Ohio' retrieved February 15, 2012, states that a monument to the July 1863 events in West Point, Ohio, was erected in 1909 by Will L. Thompson of East Liverpool which states: "This stone marks the spot where the Confederate raider General John H. Morgan surrendered his command to Major General George W. Rue, July 26, 1863, and this is the farthest point north ever reached by any body of Confederate troops during the Civil War."

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Dee A., The Bold Cavaliers: Morgan's Second Kentucky Cavalry Raiders. 1959. Republished as Morgan's Raiders, Smithmark, 1995. ISBN 0-8317-3286-5.

- Dupuy, Trevor N., Johnson, Curt, and Bongard, David L., Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, Castle Books, 1992, 1st ed., ISBN 0-7858-0437-4.

- Evans, Harold. Who Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine. Little Brown, 2004. ISBN 0316277665

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974. ISBN 978-0-394-74622-7.

- Horwitz, Lester V., The Longest Raid of the Civil War, Farmcourt Publishing, 1999, ISBN 978-0-9670267-2-5.

- Mackey, Robert E. The Uncivil War: Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861–1865. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8061-3624-0.

- Noe, Kenneth W. Perryville: This Grand Havoc of Battle. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8131-2209-0.

- Ramage, James A. Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8131-0839-1.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Duke, Basil W., Morgan's Cavalry New York, 1906.

- Gorin-Smith, Betty Jane, 'Morgan Is Coming!': Confederate Raiders in the Heartland of Kentucky. Louisville, Kentucky: Harmony House Publishers, 2006, 452 pp., ISBN 978-1-56469-134-7.

- Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Buel, Clarence C. (eds.), Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Century Co., 1884–1888.

- Mowery, David L., Morgan's Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60949-436-0.

- Rue, George Washington, Maj. (1828–1911): Celebration of the Surrender of General John H. Morgan, Ohio Archæological and Historical Society Publications: Volume 20 [1911], pp. 368–377.

- Penn, William A., Kentucky Rebel Town: Civil War Battles of Cynthiana and Harrison County, (Lexington: U. Press of Kentucky, 2016)

External links

[edit]- The History of the Thunderbolt Raiders Archived 2011-02-03 at the Wayback Machine by journalists Lee Bailey and John Hambrick

- John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail

- "The Battle of Corydon, Indiana" – Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush, which contains rare images of Morgan shown courtesy of the Civil War Museum of the Western Theater in Bardstown, Kentucky.

- "Morgan's Christmas Raid" – Article by Civil War historian/author Bryan S. Bush

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- 1825 births

- 1864 deaths

- Military personnel from Huntsville, Alabama

- American people of Welsh descent

- Confederate States Army brigadier generals

- American military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- Confederate States of America military personnel killed in the American Civil War

- American slave owners

- American Freemasons

- Escapees from United States military detention

- Lexington in the American Civil War

- Orphan Brigade

- People of Kentucky in the American Civil War

- Transylvania University alumni

- Hunt–Morgan family

- Deaths by firearm in Tennessee

- Burials at Lexington Cemetery

- American Civil War prisoners of war held by the United States