Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty

Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty C. S. I. | |

|---|---|

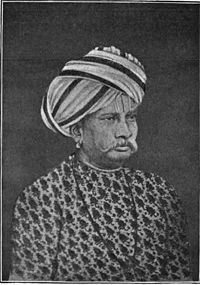

A portrait of Gajula Lakshminarasu Chetty | |

| Born | 1806 |

| Died | 1868 |

| Occupation | Merchant |

| Known for | Political activism, publicist |

Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty CSI (Telugu: గాజుల లక్ష్మీనరసు శెట్టి; 1806–1868) was an Indian merchant and political activist who founded the Madras Native Association, one of the earliest Indian political associations, and the first Indian-owned newspaper in Madras, The Crescent. He was also the second Indian to be appointed a member of the Madras Legislative Council, succeeding V. Sadagopacharlu on his death.[1] Lakshminarasu Chetty was born in 1806 to a wealthy indigo merchant Sidhulu Chetty in Madras. On completion of his initial education, Chetty entered the family trade and succeeded as a businessman. He entered politics and devoted money for social and philanthropic causes.

Early life

[edit]Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty was born in 1806 in Periamet, Madras in a Telugu-speaking Balija family.[2][3] His father, Sidhulu Chetty (సిద్ధులు శెట్టి), owned a large indigo, dye, and cloth business, and was the first Indian member of the Madras Chamber of Commerce.[1] Due to the poor schooling facilities available in India at the time, Chetty had little formal education. However, even as a boy, Chetty was interested in politics and took part in Debating Societies.[4]

Business

[edit]On completion of his education, Chetty worked as an apprentice under his father, whose business was soon afterwards renamed Sidhulu Chetty and Co.[5] The firm mainly dealt in handkerchiefs and soon grew into a thriving corporation. After Sidhulu Chetty's death, Lakshminarasu Chetty inherited the firm and expanded its network.

When the American Civil War broke out, cotton trade was temporarily suspended between the United States of America and other countries. Chetty took advantage of the situation and made huge profits by speculating on the price of cotton.[6]

Anti-proselytization activities

[edit]During the mid-19th century, Christian missionaries indulged in open proselytisation in public institutions in the Madras Presidency. Their proselytisation activities were allegedly favoured by officials of the British government, who preferred native Christians to Hindus in higher appointments in order to entice Hindu Indians to embrace Christianity. The religious stance of the Madras government was frequently condemned by the Hindu population. Chetty supported their cause, and launched agitations against conversions.

On 2 October 1844, Chetty founded the Crescent, the first Indian-owned newspaper in the Madras Presidency for the "amelioration of the condition of Hindus".[7] But right from the beginning, the newspaper faced strict government opposition. An advertisement sent to the Madras government for insertion into the government publication Fort St George Gazette was rejected. Further, the government resolved to enact a law wherein a Hindu convert to Christianity would not lose his ancestral right to own property. This was severely condemned by the Hindu community of Madras who, under the leadership of Chetty, presented a memorial to the Governor on 09 April 1845. The government eventually withdrew its plans after prolonged discussions with the agitators.

Around this time, the Madras government tried to introduce the Bible as a standard textbook for the students of the Madras University.[8] Students were often questioned on points connected to Christian theology and were denied government posts if their knowledge of Christian texts was found wanting. Hindus of the Madras Presidency protested against these measures. Chetty presided over a protest meeting at the Pachaiyappa's College on 7 October 1846 in which it was resolved to send a memorandum to the Court of Directors of the British East India Company. Their efforts were successful and moves to introduce Christian theology in the curriculum were disbanded. In 1853, the government once again tried to introduce the Bible into the educational curriculum, but its efforts were thwarted by George and John Bruce Norton and Chetty.[8]

Torture Commission

[edit]Peasants in various parts of the Madras Presidency were often subjected to cruel punishments if they failed to pay taxes on time. In 1854, with the assistance of H. Danby Seymour, a member of the British House of Commons, Chetty tried to induce the British authorities to investigate the methods of torture inflicted by the revenue collectors.[4] In July 1854, Seymour tried to introduce a motion in the British Parliament. Sir Charles Wood, President of the India Board, responded by appointing a Torture Commission in September 1854, to investigate the conduct of revenue officials. Further pressure was induced by a petition signed by Chetty and other Indians, which was presented in the House of Lords on 14 April 1856.[4]

Madras Native Association

[edit]Chetty established Madras Native Association in 1852 as a platform for educated Indians to protest against any injustice on the part of the British. It was the first Indian political organization in the Madras Presidency. Chetty served as its first president.[5][7][8] Initially, his plans had been to establish a branch of the British Indian Association in Madras; however, a separate organisation was formed instead of a branch.[7] P. Somasundaram Chettiar, a close associate of Chetty, served as the Secretary of the organization.[7] The organization frequently locked horns with Christian missionaries.[7]

In 1852, the Madras Native Association presented a detailed list of grievances to the British Parliament. It was read out at the House of Lords on 25 February 1853 by the Earl of Ellenborough along with a petition from the inhabitants of Manchester that a minister and council for India be appointed and that they be made responsible directly to the British monarch. Chetty followed it up with another petition in 1855. This petition signed by over 14,000 people beseached the British Crown to take the administration of India directly under its control.[4] These petitions resulted in the curtailment of the powers of the British East India Company eventually culminating in the transfer of sovereignty over India to the British Crown. The organisation was dissolved in 1867, one year before Chetty's death.[4]

Honours

[edit]In 1861, Chetty was created Companion of the Star of India.[6][8] Two years later, in 1863, he was nominated to the Madras Legislative Council on the death of V. Sadagopacharlu, the first Indian nominated to the Madras Legislative Council as per the Indian Councils Act 1861.[8]

Death

[edit]Chetty died in poverty in 1868, having spent all his money in his social and political activities.[5][6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b S. Muthiah (July 21, 2013). "Activism over business". The Hindu.

- ^

- Alok Kumar Kanungo, Laure Dussubieux, ed. (2021). Ancient Glass of South Asia: Archaeology, Ethnography and Global Connections. Springer Nature. p. 283. ISBN 9789811636561.

- K.H.S.S. Sundar, ed. (1994). Origins and growth of political consciousness in Andhra during the nineteenth century. University of Hyderabad. p. 153.

- A. Vijaya Kumari, Sepuri Bhaskar, ed. (1998). Social Change Among Balijas: Majority Community of Andhra Pradesh. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 9788175330726.

- M.L.Kantha Rao, ed. (1999). A study of the socio political mobility of the kapu caste in modern Andhra. University of Hyderabad. p. 93.

- ^ Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India. Palaniappa Brothers. p. 366. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8.

- ^ a b c d e "అర్జీలే అస్త్రంగా ఆంగ్లేయులపై అలుపెరగని పోరాటం". ETV Bharat (in Telugu). 15 April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "Gazulu Lakshminarasu Chetty". Indian Liberal Group. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ a b c Buckland, C. E. (1906). . Dictionary of Indian Biography. Swan Sonnenschein & Co., Lim. p. – via Wikisource. [scan

]

]

- ^ a b c d e Seal, Anil (1971). The Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century. CUP Archive. p. 198. ISBN 0521096529.

- ^ a b c d e Madras Tercentenary Commemoration Volume, Pg 348

Further reading

[edit]- Pillai, G. Paramaswaran (1897). Representative Indians. London: George Routledge & Sons, Limited. pp. 193–207.

- Srinivasachari, Rao Sahib C. S. (1939). History of the City of Madras: Written for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee, 1939. Madras: P. Varadachary & Co.