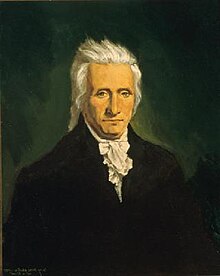

Gabriel Duvall

Gabriel Duvall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office November 23, 1811 – January 14, 1835[1] | |

| Nominated by | James Madison |

| Preceded by | Samuel Chase |

| Succeeded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland's 2nd district | |

| In office November 11, 1794 – March 28, 1796 | |

| Preceded by | John Mercer |

| Succeeded by | Richard Sprigg |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 6, 1752 Prince George's County, Province of Maryland, British America |

| Died | March 6, 1844 (aged 91) Glenn Dale, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Bryce (1787–1794) Jane Gibbon (1795–1834) |

| Signature | |

Gabriel Duvall (December 6, 1752 – March 6, 1844) was an American politician and jurist. Duvall was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1811 to 1835, during the Marshall Court. Previously, Duvall was the Comptroller of the Treasury, a Maryland state court judge, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland, and a Maryland state legislator.

Whether Duvall is deserving of the title of "the most insignificant" justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court has been the subject of much academic interest, most notably a debate between University of Chicago Law Professors David P. Currie and (now-Judge) Frank H. Easterbrook in 1983. Currie argued that "impartial examination of Duvall's performance reveals to even the uninitiated observer that he achieved an enviable standard of insignificance against which all other justices must be measured."[2] Easterbrook responded that Currie's analysis lacked "serious consideration of candidates so shrouded in obscurity that they escaped proper attention even in a contest of insignificance," and concluded that Duvall's colleague, Justice Thomas Todd, was even more insignificant.[3]

Early and family life

[edit]Gabriel Duvall was born in Prince George's County in the Province of Maryland, as the sixth child of Benjamin Duvall (1719–1801) and his wife Susanna Tyler (1718-1794),[4] both descendants of Mareen Duvall,[5] Gabriel was born and raised on land that would eventually become known as Marietta. Two of his elder brothers died in the American Revolutionary War. Duvall read law to enter the bar in Prince George's County in 1778, and practiced in Anne Arundel and Prince George’s County at least part-time until 1823.[6] In Annapolis, Maryland, he practiced in the Mayor's Court as county prosecutor beginning in 1781, and in Anne Arundel County court beginning in 1783, formally appearing in 600 cases by 1792 according to an archivist's research.

Some uncertainty remains over the spelling of Duvall's name. One scholar noted Supreme Court Reporters Cranch, Wheaton, and Peters uniformly spelled it "Duvall", but Marshall's biographer, Albert Beveridge, insisted on spelling the name with a single "l."[7] Journalist and Supreme Court specialist Irving Lee Dilliard (1904–2002) concluded persuasively that the original "DuVal" or "Duval" employed in earlier generations had become "Duvall" before the future justice was born. Later family members used "DuVal".

Gabriel Duvall was an Anglican (Episcopalian after the American Revolutionary War) and maintained pews both at St. Anne's Church, Annapolis, and his family's longstanding parish in Prince George's County, Holy Trinity Episcopal Church, Collington, originally a chapel of ease known as Henderson's Chapel for St. Barnabas' Episcopal Church, Leeland. He married twice, first in 1787 to Mary Bryce (d. 1791), daughter of Annapolis sea captain Robert Bryce. They had only one son, Edmund Bryce Duvall (1790–1831). Duvall married his second wife, Jane Gibbon Duvall (1757 – 1834), daughter of sea captain James Gibbon and Mary Gibbon. Widowed, Mary Gibbon ran a boarding house in Philadelphia where her daughter Jane also worked. Gabriel Duvall and other members of Congress stayed at the Gibbons’ boarding house. He met Jane at the boarding house during his federal service in Philadelphia. They married on May 5, 1795, at Christ Church, Philadelphia. Her mother, Mary Gibbon, came to live with them in the Duvall’s D.C. residence during her last years (she died in 1810 and was buried in the Duvall family cemetery at WigWam, a part of Marietta plantation). Jane Duvall died in 1834 and Gabriel Duvall died in 1844, both at Marietta.

The Duvall family enslaved anywhere from nine to forty people at their tobacco plantation, Marietta, between 1783 and 1864, including multiple generations of the Duckett, Butler, Jackson, and Brown families at Marietta.

Career

[edit]Duvall was a clerk for the Maryland Council of Safety (which managed the state militia) from 1775 to 1777, and for the Maryland House of Delegates from 1777 to 1781.[6]

He participated in the American Revolutionary War, first as a Muster master and commissary of stores in 1776, then as a private in the Maryland militia, where he fought in the Battle of Brandywine.[8] He was a Commissioner to preserve confiscated British property from 1781 to 1782, then a member of Maryland Governor's Council from 1782 to 1785.[9]

He was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, serving there from 1787 to 1794.[6] He served one term as a U.S. Representative from the second district of Maryland, from November 11, 1794, to March 28, 1796.[6] He was then Chief Justice of the Maryland General Court from 1796 to 1802, and was the first U.S. Comptroller of the Treasury from 1802 to 1811.[6]

As an attorney, Gabriel Duvall worked on behalf of over 120 enslaved men, women, and children who sued in court for their freedom. In this way he established his reputation as a successful lawyer who won nearly 75% of those enslaved people’s petitions for freedom.[10] Paradoxically, Duvall fought against the petition of freedom filed by Thomas and Sarah Butler, whose family Duvall enslaved at Marietta (1805–1831).

Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

[edit]On November 15, 1811, Duvall was nominated by President James Madison to an associate justice seat on the Supreme Court of the United States vacated by fellow Marylander Samuel Chase.[11] Duvall was confirmed by the United States Senate on November 18, 1811, and received his commission the same day.[11] He was sworn into office on November 23, 1811, and served on the Court until January 14, 1835.[1]

In the 23 years he sat on the Supreme Court, Duvall penned an opinion in only 18 cases: 15 majority opinions, two concurrences, and one dissent. The Court during this time was largely a vehicle for Chief Justice John Marshall's belief in a strong Federal government and the associate justices rarely dissented, with Marshall himself writing the large majority of opinions. The one time when Duvall dissented was in the case of Mima Queen and Child vs. Hepburn (1813) where he was the sole dissenting justice in a case that ruled whether the daughter of an ex-slave could provide hearsay evidence that her mother was free at the time of her birth. Duvall wrote that the evidence should be allowed, and "people of color from their helpless condition under the uncontrolled authority of a master, are entitled to all reasonable protection."[12] In Duvall’s 1813 dissent, he argued that, “It will be universally admitted that the right to freedom is more important than the right of property”. However, the court denied the Queens their freedom by disallowing hearsay as evidence for their petition for freedom.

He remained on the U.S. Supreme Court until retiring shortly after his 82nd birthday. According to one of Chief Justice Marshall's biographers, Duvall "became distinguished for holding on to his seat for many years after he had become aged and infirm because he was fearful of who would replace him."[13] According to his biographer, Irving Dillard, in his last few years on the Court, Duvall was "so deaf as to be unable to participate in conversation."[14] Prof. Currie retorts that: "There is no proof ... that Duvall was either deaf or unable to speak while on the Court".[15]

Majority opinions

[edit]In his 24 years on the Supreme Court, Duvall authored 15 majority opinions: Freeland v. Heron, Lenox & Co. (1812),[16] United States v. January (1813),[17] United States v. Patterson (1813),[18] Crowell v. McFadon (1814),[19] Prince v. Bartlett (1814),[20] United States v. Tenbroek (1817),[21] The Neptune (1818),[22] Boyd's Lessee v. Graves (1819),[23] The Frances & Eliza (1823),[24] Walton v. United States (1824),[25] Piles v. Bouldin (1826),[26] Rhea v. Rhenner (1828),[27] Parker v. United States (1828),[28] Nicholls v. Hodges (1828),[29] and Le Grand v. Darnall (1829).[30]

Commercial law

[edit]Freeland concerned commercial law. In Freeland, a diversity suit concerning a commercial transaction between American and English merchants, Duvall enforced the English choice of law clause of the contract, applying "a rule of the Chancery Court and of merchants," namely that: "When one merchant sends an account current to another residing in a different country, between whom there are mutual dealings, and he keeps it two years without making any objections, it shall be deemed a stated account, and his silence and acquiescence shall bind him, at least so far as to cast the onus probandi on him."[31]

Bankruptcy

[edit]January and Prince v. Bartlett concerned bankruptcy. In January, according to Prof. John Paul Jones, Duvall became the "architect of the federal rule that the ordinary practice of permitting first the debtor and alternatively the creditor to choose to which among competing obligations a payment should be applied did not pertain when different sureties, under distinct obligations, were interested."[32] In a 2007 address to the Federalist Society, Chief Justice John Roberts jokingly referred to this as "the Duvall rule."[33] According to Prof. Jones, Prince v. Bartlett "is still cited regularly for the distinction first articulated in that case between bankruptcy and mere insolvency."[32]

Debts to the United States

[edit]Patterson, Walton, and Parker concerned debts to the United States (a subject with which Duvall was familiar due to his experience as Comptroller of the Treasury). Patterson reversed a judgment for the debtor, holding that the debtor "could not be justly entitled to credit until the money was in the hands of some public officer authorized to receive it."[34] Walton affirmed a judgment against a debtor, holding that, while ordinarily "a security under seal extinguishes a simple contract debt," in the case of public debts, "the account and the bond are distinct from each other. The official bond is not given for the balance due; it is a collateral security . . . ."[35] Parker affirmed a judgment for the United States to recoup the payment of double rations to a military officer because the doubling was not authorized by the President or the Secretary of War, as required by the statute.[36]

Federal customs law

[edit]Crowell v. McFadon, Tenbroek, The Neptune, and The Frances & Eliza concerned the enforcement of federal customs law. In Crowell v. McFadon, Duvall reversed a trover judgment from the Massachusetts courts against a federal customs collector enforcing the Embargo Act of 1807.[37] The Neptune upheld the forfeiture of an unregistered vessel.[38] The Frances & Eliza held that the Navigation Act of 1818 did not apply to a British vessel bringing goods from a non-British port to the United States merely because the vessel had stopped for provisions at a British port en route.[39] Tenbroek concerned statutory construction. The decision was, in effect, an advisory opinion. Duvall wrote:

It is the opinion of this court, that there is no error in the judgment of the circuit court. This opinion is given on the request of the Attorney-General; it being probable that the same question may frequently occur. But, as this cause is improperly brought before this court by writ of error, having been first carried from the district to the circuit court by the same process, it is dismissed.[40]

Land law

[edit]Boyd's Lessee v. Graves and Piles v. Bouldin concerned land law. Boyd's Lessee v. Graves held that an agreement as to the location of a survey line was not a contract, and thus was not barred by the statute of frauds.[41] Piles v. Bouldin held that land grants were to be interpreted by the judge (not the jury), and reversed the judgement below failing to give effect to the statute of limitations.[42]

Maryland law

[edit]Rhea v. Rhenner, Nicholls v. Hodges, and Le Grand v. Darnall concerned Maryland law (which Duvall was familiar with as a former Maryland state judge). Rhea v. Rhenner concerned the ability of a woman to contract under Maryland law. Elizabeth Rhea had been abandoned by her first husband William Erskine for five years and attempted to remarry to Daniel Rhea. She executed a deed in payment of a debt that she had contracted for herself. Duvall held that her second marriage was invalid because she had only been abandoned for five years, rather than the requisite seven years, and that no contract signed by her in the absence of her first husband could be valid.[43] Nicholls v. Hodges held that under Maryland law the claim of an executor against an estate stands on an equal footing with other claims.[44] Le Grand v. Darnall held that a jury was justified in presuming a deed of manumission because a slave owner permitted former slaves and their descendants to own property and contract debts within three miles of his residence.[45]

Concurrences

[edit]Duvall authored a one-sentence concurrence in McIver's Lessee v. Walker (1815): "My opinion is that there is no safe rule but to follow the needle."[46] Duvall authored a brief seriatim opinion in Beatty v. Maryland (1812).[47]

Dissents

[edit]For all of Duvall's tenure, John Marshall presided as Chief Justice. In only three cases does the record show the two men holding different opinions. Duvall dissented without opinion in Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819) and Evans v. Eaton (1822),[48] and with opinion in Queen v. Hepburn (1813).[49] In Dartmouth College, Duvall issued his sole "opinion" in a constitutional case.[7] The notation in the United States Reports reads in full: "Duvall, Justice, dissented."[50] In Queen v. Hepburn,[51] Duvall would have authorized the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia to accept hearsay evidence proving the emancipation of a slave by her owner, but the rest of the Court, per the Chief Justice, decided against it.[49]

Death

[edit]

Duvall lived for a decade after his wife's death and his own retirement (on grounds of deafness). He died, aged 91, in Prince George's County, Maryland and was buried in the family cemetery at Wigwam, one of the plantations he owned.[6] Justice Duvall's home, "Marietta", (built 1812-1813) became his permanent residence when his Washington D.C. mansion was used by the State Department after the British burned many Federal buildings during the War of 1812. Today, Marietta House Museum is open to the public and operated as an historic house museum by M-NCPPC.[52][53] At his death, Duvall enslaved 39 enslaved men, women, and children, and owned approximately $14,000 in bank stock, 528 volumes of law books, 400 books on other subjects, in addition to 700 acres of real estate in Prince George's County, and other property.[54] His principal heirs were his sister, Sarah Simpson (who died the same year), and four grandchildren (Marcus, Edmund, Mary Frances and Gabriella Augusta Duvall).[55] His remains were reinterred on Marietta House Museum's grounds circa 1987, as were other family graves endangered by development in the area. In 1959, Maryland named a new high school near Duvall's former home, DuVal High School, and it continues today.

Significance

[edit]In 1939, Ernest Sutherland Bates, the author of The Story of the Supreme Court, called Duvall "probably the most insignificant of all Supreme Court Judges."[56] The characterization was rejected by Irving Dilliard's biographical entry in The Justices of the United States Supreme Court 1789–1969 (1969).[57] Dilliard did not propose an alternative candidate.[2]

Professor David P. Currie of the University of Chicago Law School joined the issue in 1983 in the 50th anniversary issue of the University of Chicago Law Review. He argued that "impartial examination of Duvall's performance reveals to even the uninitiated observer that he achieved an enviable standard of insignificance against which all other Justices must be measured."[2] Currie notes that: "On the quantitative scale of PPY [pages of published opinions per year], therefore, modified by common sense and a spirit of fair play, Duvall seems to me far and away the most insignificant of his colleagues during the time of Chief Justice Marshall."[15] Prof. Currie proposed several "Indicators of Insignificance (IOI)" that he used to compare Duvall to other candidates, such as: Thomas Johnson,[58] Robert Trimble,[58] John Rutledge,[59] Bushrod Washington,[60] Henry Brockholst Livingston,[60] Thomas Todd,[60] John McKinley,[61] Nathan Clifford,[62] Alfred Moore,[63] Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II and Joseph Rucker Lamar,[64] William Henry Moody,[65] Horace Harmon Lurton,[65] George Shiras, Jr.,[65] William R. Day,[65] John Hessin Clarke,[65] and William Cushing.[65]

Then-Professor, now-Judge Frank H. Easterbrook replied to Currie's article. Easterbrook (who spelled Duvall's name as "Duval[l]" with the last letter in brackets) wrote: "I also became worried that Currie had slighted—even overlooked!—the legitimate claims of others to the honors he bestowed on Gabriel Duval[l]. Could it be that Currie's efforts were simply pseudo-science employed in the pursuit of some predetermined plan to award Duval[l] the coveted prize without serious consideration of candidates so shrouded in obscurity that they escaped proper attention even in a contest of insignificance?"[66] Easterbrook concludes: "Of the finalists, Todd and Duval[l], one disqualified himself by writing some significant opinions. True, Duval[l] tried to atone for this by remaining mute (he was deaf by then as well) after his opinion in LeGrand, but it was too late. His Significant Acts had disqualified him. The winner by default—in what other way can one win this kind of contest?—is Thomas Todd. Long may he reign."[67]

See also

[edit]- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Marshall Court

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Currie, 1983, at 466.

- ^ Easterbrook, 1983, at 482, 496.

- ^ Maryland State Archives, biographical notes Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine p. 4

- ^ "Gabriel Duvall, Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court". geni.com. December 6, 1752.

- ^ a b c d e f Christopher L. Tomlins, The United States Supreme Court: The Pursuit of Justice 476–77 (2005).

- ^ a b Currie, 1983, at 468.

- ^ Kenneth Jost, The Supreme Court A to Z 171 (2007).

- ^ 4 West's Encyclopedia of American Law 171 (1998).

- ^ Thomas, William G. (2020). A question of freedom : the families who challenged slavery from the nation's founding to the Civil War. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-23412-1. OCLC 1198444611.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b David G. Savage & Joan Biskupic, Guide to the US Supreme Court 993 (2004).

- ^ Easterbrook, 1983, at 491.

- ^ Leonard Baker, John Marshall: A Life in Law 539 (1974).

- ^ Dillard, 1969, at 427.

- ^ a b Currie, 1983, at 471.

- ^ Freeland v. Heron, Lenox & Co., 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 147 (1812).

- ^ United States v. January, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 572 (1813).

- ^ United States v. Patterson, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 575 (1813),

- ^ Crowell v. McFadon, 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 94 (1814).

- ^ Prince v. Bartlett, 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 431 (1814).

- ^ United States v. Tenbroek, 15 U.S. (2 Wheat.) 248 (1817).

- ^ The Neptune, 16 U.S. (3 Wheat.) 601 (1818).

- ^ Boyd's Lessee v. Graves, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 513 (1819).

- ^ The Frances & Eliza, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 398 (1823).

- ^ Walton v. United States, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 651 (1824).

- ^ Piles v. Bouldin, 24 U.S. (11 Wheat.) 325 (1826).

- ^ Rhea v. Rhenner, 26 U.S. (1 Pet.) 105 (1828).

- ^ Parker v. United States, 26 U.S. (1 Pet.) 293 (1828).

- ^ Nicholls v. Hodges, 26 U.S. (1 Pet.) 562 (1828).

- ^ Le Grand v. Darnall, 27 U.S. (2 Pet.) 664 (1829).

- ^ Freeland, 11 U.S. at 151.

- ^ a b John Paul Jones, "Gabriel Duvall Archived May 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" (January 20, 2012).

- ^ John Roberts, Address to the Federalist Society[usurped] (November 16, 2007).

- ^ Patterson, 11 U.S. at 576.

- ^ Walton, 22 U.S. at 656.

- ^ Parker, 26 U.S. at 293–98.

- ^ Crowell v. McFadon, 12 U.S. at 98.

- ^ The Neptune, 16 U.S. at 602–10.

- ^ The Frances & Eliza, 21 U.S. at 404–06.

- ^ Tenbroek, 15 U.S. at 259.

- ^ Boyd's Lessee v. Graves, 17 U.S. at 517–18.

- ^ Piles v. Bouldin, 24 U.S. at 330–32.

- ^ Rhea v. Rhenner, 26 U.S. at 108–09.

- ^ Nicholls v. Hodges, 26 U.S. at 564–66.

- ^ Le Grand v. Darnall, 27 U.S. 667–70.

- ^ McIver's Lessee v. Walker, 13 U.S. (9 Cranch) 173, 179 (1815) (Duvall, J., concurring).

- ^ Beatty v. Maryland, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 281, 284 (1812) (Duvall, J.).

- ^ Evans v. Eaton, 20 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 356, 452 (1822) (Duvall, J., dissenting).

- ^ a b Queen v. Hepburn, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 290, 298 (1813) (Duvall, J., dissenting).

- ^ Trs. of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 518, 713 (1819) (Duvall, J., dissenting).

- ^ Mima Queen & Louisa Queen v. John Hepburn, O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family (accessed Nov. 4, 2015) Archived September 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine This case page includes legal records and proceedings from the Queen case including a Supreme Court Report outlining Duvall’s dissent.

- ^ Patricia Chambers Walker & Thomas Graham, Directory of Historic House Museums in the United States 142 (2000).

- ^ "Marietta House Museum". history.pgparks.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Maryland State Archives notes p. 9.

- ^ Maryland State Archives, biographical notes Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine p. 21

- ^ Ernest Sutherland Bates, The Story of the Supreme Court 109 (1936).

- ^ Dilliard, 1969, at 428.

- ^ a b Currie, 1983, at 467.

- ^ Currie, 1983, at 467, 471.

- ^ a b c Currie, 1983, at 470.

- ^ Currie, 1983, at 472–73.

- ^ Currie, 1983, at 473–77.

- ^ Currie, 1983, at 479.

- ^ Currie, 1983, 479–80.

- ^ a b c d e f Currie, 1983, at 480.

- ^ Easterbrook, 1983, at 482.

- ^ Easterbrook, 1983, at 496.

References

[edit]- David P. Currie, The Most Insignificant Justice: A Preliminary Inquiry, 50 U. Chi. L. Rev. 466 (1983).

- Irving Dilliard, Gabriel Duvall, in 1 The Justices of the United States Supreme Court 1789–1969, at 419 (H. Friedman & F. Israel eds. 1969).

- Frank H. Easterbrook, The Most Insignificant Justice: Further Evidence, 50 U. Chi. L. Rev. 481 (1983).

Further reading

[edit]- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Gabriel Duvall, O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family (accessed Nov. 4, 2015) This person page networks the involvement of Gabriel Duvall in the legal records and case files of petition for freedom suits between 1800 and 1862 in Washington, D.C.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Thomas, William G. A Question of Freedom: The Families Who Challenged Slavery from the Nation's Founding to the Civil War. Yale University Press, 2022. ISBN 9780300261509

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- White, G. Edward. The Marshall Court & Cultural Change, 1815–35. Published in an abridged edition, 1991.

External links

[edit]- Gabriel Duvall at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- 1752 births

- 1844 deaths

- 18th-century American judges

- 19th-century American judges

- 18th-century American legislators

- Democratic-Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland

- Duvall family

- Maryland Whigs

- People from Glenn Dale, Maryland

- United States federal judges appointed by James Madison

- Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law

- American slave owners