French submarine Plongeur

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

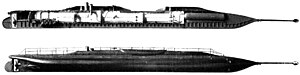

The French submarine Plongeur, 1863.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Operator | French Navy |

| Ordered | 1859 |

| Builder | Arsenal de Rochefort |

| Laid down | 1 June 1860 |

| Launched | 16 April 1863 |

| Stricken | 2 February 1872 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 381 t (420 tons) in displacement |

| Length | 45 m (146 ft)[1] |

| Beam | 3.7 m (12 ft) |

| Propulsion | Compressed air engine with 153 m3 (5,403 ft3) of compressed air at 12.5 bar (1.25 MPa, 180 psi). |

| Speed | 4 kn (7.2 km/h) |

| Range | 5 nmi (9 km) |

| Test depth | 10 metres |

| Complement | 12 |

| Armament | Spar torpedo |

Plongeur (French for "Diver") was a French submarine launched on 16 April 1863. She was the first submarine in the world to be propelled by mechanized (rather than human) power.

Captain Siméon Bourgeois, who made the plans, and naval constructor Charles Brun began working on the design in 1859 at Rochefort.

Design

[edit]

In 1859 the Board of Construction (Conseil des travaux) called naval engineers for designs for a submarine and reviewed three, choosing that submitted by Siméon Bourgeois (later Admiral) and Charles Brun, naming the project Plongeur[2] with the code name Q00.

The submarine used a compressed-air engine, propelled by stored compressed air powering a reciprocating engine.[3] The air was contained in 23 tanks holding air at 12.5 bar (1.25 MPa, 180 psi), taking up a huge amount of space (153 m³/5,403 ft³), and requiring the submarine to be of unprecedented size. The engine had a power of 60 kW (80 hp), and could propel the submarine for 5 nmi (9 km), at a speed of 4 kn (7.2 km/h).

Compressed air was also used to empty its ballast tanks, which had a volume of 53 m3 (1,872 ft3). Ballast was 212 t (234 tons), including a security ballast of 34 t (37 tons).

The submarine was armed with a ram to break holes in the hull of enemy ships, and an electrically fired spar torpedo, fixed at the end of a pole,[4] though later Admiral Bourgeois (who was, after 1871, chairman of the Commission on Submarine Defenses) opposed the use of torpedoes as the primary weapon in commerce warfare.[5]

The submarine was 43 m (140 ft) long and 381 t (420 tons) in displacement.

A support ship, the Cachalot, followed her in order to resupply the compressed air necessary to her propulsion.

A small lifeboat (8 × 1.7 m; 26 × 5.6 ft) was provided for the escape of the 12-man complement.

Operational history

[edit]

The submarine was commanded by Lieutenant de Vaisseau Marie-Joseph-Camille Doré.

On 6 October 1863, Plongeur made her first trials by sailing down the Charente River, to the harbour of the Cabane Carrée.

On 2 November 1863, Plongeur was towed to Port-des-Barques, where her first underwater trials were planned. Because of poor weather conditions, the submarine was eventually towed to La Pallice and then to the harbour (Bassin à flot) of La Rochelle

On 14 February 1864, during trials in the Bassin à flot, the engine raced due to an excessive admission of compressed air, and the submarine bumped into the quay. Trials were stopped.

On 18 February 1864, Plongeur was towed to La Pallice and dived to 9 m (30 ft).

Stability problems due to its length limited the submarine to dives to a maximum depth of 10 m (33 ft). The front of the submarine would tend to dive first, hitting the bottom, so that the submarine would glide forward. Pumps were installed to compensate for the tilt, but proved too slow to be effective. The installation of longitudinal rudders would have improved stability as later demonstrated by the submarines Gymnote and Gustave Zédé .

A model of Plongeur was displayed at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, where it was studied by Jules Verne,[6] who used it as an inspiration[7][8] for his novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.[9]

After various experiments, she was stricken by the French Navy on 2 February 1872.

Conversion

[edit]

The submarine was used as a water tanker from 1 January 1873. She was assigned to the harbour of Rochefort. In 1927, upon the closure of the arsenal at Rochefort, she was transferred to the Mediterranean at Toulon. She was decommissioned on 25 December 1935, and sold on 26 May 1937.[10]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Farnham Bishop. The Story of the Submarine. p. 57.

- ^ Le Masson, H. (1969) Du Nautilus (1800) au Redoubtable (Histoire critique du sous-marin dans la marine française), Paris pp.55–59

- ^ Kohnen, W. (2009). Human exploration of the deep seas: fifty years and the inspiration continues. Marine Technology Society Journal, 43(5), 42-62.

- ^ Swinfield, J. (2014). Sea Devils: Pioneer Submariners. The History Press.

- ^ Røksund, A. (2007). The jeune ecole: the strategy of the weak. Brill.

- ^ Payen, J. (1989). De l'anticipation à l'innovation. Jules Verne et le problème de la locomotion mécanique.

- ^ Compère, D. (2006). Jules Verne: bilan d'un anniversaire. Romantisme, (1), 87-97.

- ^ Seelhorst, Mary (2003) 'Jules Verne. (PM People)'. In Popular Mechanics. 180.7 (July 2003): p36. Hearst Communications.

- ^ Notice at the Musée de la Marine, Rochefort

- ^ Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours. Vol. 1. Group Retozel-Maury Millau. p. 354. ISBN 978-2-9525917-0-6. OCLC 165892922.

Bibliography

[edit]- Garier, Gérard (n.d.). L'odyssée technique et humaine du sous-marin en France [The Technical and Human Odyssey of the Submarine in France: From Plongeur (1863) to Guêpe (1904)] (in French). Vol. 1: Du Plongeur (1863) aux Guêpe (1904). Bourg-en-Bresse, France: Marines édition. ISBN 2-909675-19-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Jones, Colin (1996). "Entente Cordiale, 1865". In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- Roberts, Stephen S. (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4533-0.